Abstract

Anatase TiO2 modified FeS nanowires assembled by numerous nanosheets were synthesized by using a typical hydrothermal method. The carbon-free nanocoated composite electrodes exhibit improved reversible capacity of 510 mAh g−1 after 100 discharge/charge cycles at 200 mA g−1, much higher than that of the pristine FeS nanostructures and long-term cycling stability with little performance degradation even after 500 discharge/charge cycles at current density of 400 mA g−1. Full batteries fabricated using the FeS@TiO2 nanostructures anode and the LiMn2O4 nanowires cathode with excellent stability and good rate capacities could also be achieved. The enhanced electrochemical performance of the composite electrodes can be attributed to the improved conductively of the integrated electrodes and the enhanced kinetics of lithium insertion/extraction at the electrode/electrolyte interface because of the incorporation of anatase TiO2 phase.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Lithium-ion batteries, one of the most promising energy-storage devices and providing the power for almost all current portable electronics, have attracted worldwide attention accompanying the increasing concerns about the limited global energy supply and the degradation of living environment1,2,3,4,5,6. The performances of lithium-ion batteries depend largely on the properties and structures of electrode materials for lithium storage7,8. Two-dimensional (2D) nanostructures are of great interest in lithium storage due to their shortened paths for fast lithium ion diffusion and large exposed surface offering more lithium-insertion channels9,10. 2D nanostructures of some layered-structured metal sulfides, such as WS2 and MoS2 have been actively studied as electrode materials in lithium-ion batteries due to their structural advantages in reversible Li storage processes11,12,13,14. However, the metal elements in these sulfides are relatively heavy, which may limit their theoretical specific energies densities10.

Iron sulfides are interesting materials for energy storage applications due to their cost effectiveness and abundance in nature. Furthermore, they have a higher Li-insertion voltage (ca. 1.3 V vs Li+/Li) than that of commercial graphite anode (below 0.2 V vs Li+/Li), which can avoid reduction of electrolyte on the surface of the electrode and formation of the solid-electrolyte interphase (SEI) layer (usually occurring below 1.0 V vs Li+/Li). Several kinds of iron sulfides have been studied as electrodes for lithium-ion batteries, which storage Li via a conversion reaction15,16. However, the products after the discharge process in such batteries are insulating polysulfides (Li2Sx, 1 < x < 8), which could easily dissolve in liquid electrolyte16. Besides losing active material, the dissolved polysulfides also deteriorate the conductivity of the electrolyte and the electrode leading to capacity degradation17,18,19. What's more, part of the insulating reaction products cover the electrode and prevent its further electrochemical reactions. Recently, carbon-based capping the sulfides into thin wrapping layers is a successful strategy to reduce polysulfides dissolution into the electrolyte. However, because of safety issues concerning carbon materials, great efforts are also directed to carbon-free coatings for achieving superior rate performance, high tap density and surface stability20. At this stage, a novel iron sulfides nanostructures with 2D morphology for lithium ion transport and uniform carbon-free conducting nanocoating layer are still highly desired.

Herein, we successfully exhibit a novel one-dimensional anatase TiO2 modified FeS nanostructure composed of 2D graphene-like FeS nanosheets via a facile hydrothermal growth method followed with the treatment in TiCl4 solution. As expected, the TiO2 modified FeS nanostructure displayed excellent Li storage properties with considerable capacity of 520 mAh g−1 after 100 discharge/charge cycles at 200 mA g−1, superior cyclic stability (456 mAh g−1 even after 500 discharge/charge cycles at 400 mA g−1) and improved rate capability compared with those of the pure FeS nanostructures. The enhanced electrochemical performances of the composite electrodes can be attributed to the large exposed electrochemical active surface, the improvement of lithium diffusion coefficient and the electrical conductivity of the overall electrode because of the introduction of anatase TiO2 phase, which were confirmed by the investigation of the lithium storage performance, electrochemical impedance and the kinetics of lithium ion insertion/extraction.

Results

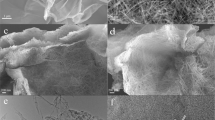

The FeS@TiO2 nanostructures were synthesized via a facile hydrothermal method combined with a post-treatment process. Figure 1 shows the X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of the FeS products before and after TiO2 treatment. All peaks in Figure 1a can be well indexed as hexagonal FeS (JCPDS Card No. 03-065-3356, space group P-62c). As for the FeS@TiO2 sample shown in Figure 1b, all the diffraction peaks of FeS remain unchanged, while the peak located at 25.2° matches well with the (101) plane of anatase TiO2 (JCPDS Card No. 01-065-9124), indicating the formation of anatase TiO2. The morphology and microstructures of the as-prepared products were characterized by field-emission scanning electron microscopy (FE-SEM) as illustrated in Figure 2. One-dimensional (1D) wire-like materials with lengthes of tens of micrometers on a large scale can be obtained for the FeS@TiO2 nanostructures (Figure 2a). Further observation of the SEM image in Figure 2b, we can clearly see that the wire-like nanostructures were assembled by numerous 2D nanosheets, being in sharp contrast with the smooth surface of the precursor before calcination (Figure S1), while keeping well with the pure FeS nanostructures (Figure S2), due to the running away of organics in the precursor. The corresponding energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) (Figure 2c) suggests the existence of Fe, S, Ti and O in the resultant FeS@TiO2 nanostructures, further confirm the introduction of TiO2, in good agreement with the XRD result. In the spectrum, the peak of Pt comes from the deposited platinum when prepared for SEM characterization. The corresponding elemental mapping of Fe, S, Ti and O in the FeS@TiO2 nanostructures is shown in Figure S3, revealing the uniform dispersion of those elements. Besides, the EDS pattern and the corresponding elemental mapping of Fe and S in the pure FeS nanostructures are also depicted in Figure S4 and S5.

Typical TEM image of an individual FeS@TiO2 nanostructure was shown in Figure 2d, where a lot of nanosheets assemble into the 1D composite nanostructure can be seen. Further observation of the nanosheet (Figure S6) revealed that TiO2 nanoparticles were implanted on the surface of FeS nanosheet. Figures 2e and 2f show the high-resolution TEM (HRTEM) images of the FeS nanosheet and TiO2 nanoparticle in the composite nanosheets. The well-resolved periodic lattice fringe with an interplanar distance of 0.48 nm comes from the (101) plane of hexagonal FeS (Figure 2e). Two sets of lattice fringes with inter-plane spacing of 0.24 and 0.35 nm indicated in the HRTEM image (Figure 2f) are attributed to the (004) and (101) planes of the anatase TiO2 phase, respectively.

For the formation of FeS nanosheets, it is believed that the annealing temperature plays an important role in determining their final shapes. Previously, people reported that nanowires were obtained once the annealing temperature was set at 200–300°C21. While in our case, we increased the annealing temperature to 500°C and nanosheets assembled nanostructures were thus obtained. At a higher temperature, combined with the evaporation the organics from the precursors, the rapid diffusion process of the atoms may take place across the interface (the amorphous layers, grain boundaries and so on) to allow the formation of the hexagonal FeS nanosheets10, which may be attributed to the confined growth within the (001) plane of the hexagonal symmetrical crystals22,23. With the reaction went along, the novel nanostructures assembled by nanosheets were collected.

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) was employed to analyze the information on the surface chemical compositions and the valence states of the FeS@TiO2 nanostructures. Figure 3a shows the XPS spectrum of the S 2p core-level. Two signals at 161.5 and 167.5 eV can be attributed to S 2p3/2 and S 2p1/2, respectively, characteristic peaks of FeS. The core level spectra of Fe 2p are shown in Figure 3b. Peaks corresponding to 708.4 eV and 721.6 eV are attributed to Fe2+ states coming from FeS phase, whereas 710.5 eV and 723.4 eV are ascribed to Fe3+ states, which may be attributed to the Fe3+ formed from iron and oxide elements. The peak of O 1s (Figure 3c) is centered at 530.2 eV, which is attributed to the O2+ forming oxide with titanium. Fig. 3d presents the XPS spectra of Ti 2p doublet peaks. The binding energy of Ti 2p1/2 and Ti 2p3/2 was observed at approximately 464.2 eV and 458.5 eV, respectively. The splitting data between the Ti 2p1/2 and Ti 2p3/2 core levels are 5.7 eV, indicating a normal state of Ti4+ in the anatase TiO224. These results indicate that anatase TiO2 phase have been introduced successfully into the FeS nanostructures.

To demonstrate the effect of the introduced anatase TiO2 in improving the lithium storage performance, we investigate the electrochemical properties of the pristine FeS and FeS@TiO2 nanostructures as anode materials for lithium batteries, respectively. Figures 4a and 4b show the discharge/charge voltage profiles of the FeS and FeS@TiO2 nanostructures electrodes at a current density of 200 mA g−1 between 0.01 and 3.0 V versus Li+/Li for the first cycle, respectively. A quite distinct plateau at 1.25 V is observed, which is caused by a reaction between iron sulfides and lithium with the formation of Fe and Li2−xFeS2 phases depending on the quantity of lithium transfer per pyrrhotite25. Another plateau exists between 0.8 and 0.2 V, which is mainly attributed to the formation of Li2FeS2 and the solid electrolyte interface (SEI) layer on the electrode surface26. The FeS and FeS@TiO2 nanostructures electrodes deliver large initial discharge capacity of 900 and 920 mAh g−1 during the first cycle, which may be attributed to the form of SEI layer and the irreversible reaction between Li and FeS as indicated in the following reactions:

In the charge profiles, voltage slopes can be observed at 1.9–2.0 V, which is associated with the oxidation process of Fe to Li2FeS227. No significant differences of the voltage profiles indicate that the reaction between the introduced TiO2 and lithium is too feeble to contribute to the total capacity of FeS@TiO2 electrode.

Stable cyclic performance of electrode materials is important for practical application of lithium-ion batteries. The discharge/charge cycling stability of the FeS and FeS@TiO2 nanostructures electrodes were examined at a current density of 200 mA g−1 between 0.01 and 3.0 V. As evidenced in Figure 4c, the composite electrode shows considerable enhanced discharge/charge capacity with respect to the pure FeS electrode during all the 100 cycles. The FeS@TiO2 nanostructures electrode exhibits a discharge capacity of 505 mAh g−1 during the 15 th cycle and remains at 510 mAh g−1 after 100 cycles, which are much higher than those of the pure FeS electrode (320 and 266 mAh g−1 during the 15 th and after 100 cycles, respectively). To better understand the advantage of the FeS@TiO2 nanostructures in lithium storage, the rate performance of the FeS@TiO2 nanostructures electrode is also investigated (Figure 4d). Obviously, compared with the pristine FeS electrode, the specific capacities of the composite electrode are substantially increased at all investigated discharge/charge rates from 100 to 4000 mA g−1. It depicts that the ninth cycle discharge capacities are around 705, 474, 382, 283 and 160 mAh g−1 at current densities of 100, 500, 1000, 2000 and 4000 mA g−1, respectively, which are about two times larger than those of the pristine FeS electrode (407, 235, 179, 121 and 60 mAh g−1). These results reveal that the incorporation of anatase TiO2 into FeS nanostructures can greatly enhance the electrochemical performance for lithium storage.

To get more information about the electrochemical properties of the FeS@TiO2 nanostructures electrode, the cyclic performance was also carried out at current densities of 100, 400 and 800 mA g−1 as revealed in Figure 5a. When tested at a low current density of 100 mA g−1, the capacity of the composite electrode is as high as 635 mAh g−1 after 100 discharge/charge cycles, much higher than that of the C@FeS nanoplates electrode10. Importantly, the FeS@TiO2 nanostructures electrode still exhibits an excellent cyclic performance at much higher current densities of 400 and 800 mA g−1 and the capacities reach 440 and 355 mAh g−1 after 100 discharge/charge cycles. The corresponding coulombic efficiencies of the electrode cycled at 100 to 800 mA g−1 were shown in Figure 5b. The coulombic efficiencies (nearly 100%) are still highly expected for the composite electrode, though different discharge/charge current densities are applied, further demonstrating the excellent lithium storage performance of the FeS@TiO2 nanostructures electrode. Furthermore, the composite electrode exhibits satisfactory cycling performance as evidenced in Figure 5c and 5d. The specific capacity of the composite is 430 mAh g−1 after 500 discharge/charge cycles at 400 mA g−1 with a coulombic efficiency of 99%, demonstrating the high cyclic stability and good reversibility of the FeS@TiO2 nanostructures electrode.

To explore the potential application of the FeS@TiO2 nanostructures as the anode material of full battery, spinel LiMn2O4 nanowires were synthesized and selected as the cathode material because of its three-dimensional tunnel structure for the migration of lithium ions and advantage of fast charging resulted from the stable delithiated structure28. All peaks in the XRD pattern of the as-synthesized LiMn2O4 nanowires (Figure S7) can be well indexed as spinel LiMn2O4 (JCPDS Card No. 01-089-8325). Figure S8 shows the SEM image of the as-synthesized LiMn2O4 nanowires with uniform diameter of 200 nm and length of 10 um. The electrochemical performances of the as-prepared LiMn2O4 nanowires were first evaluated as demonstrated in Figures 6a and 6b. The LiMn2O4 nanowires electrode exhibits impressive specific capacities (82–94 mAh g−1 at 500 mA g−1), high coulombic efficiency of 99% and excellent cycling performance with capacity retention more than 87% after 100 charge/discharge cycles. Galvanostatic charge-discharge curves of the half cell based on the LiMn2O4 nanowires electrode (Figure S9) display expected discharge plateau potentials of 4.05 and 3.9 V at 500 mA g−1, in according with the previous report28. As can be seen in Figure 6b, the cathode shows capacities of 89, 85, 78, 70 and 62 mAh g−1 at current densities ranged from 100 to 2000 mA g−1. The little capacity loss with the increase of the charge/discharge current densities indicates the superior rate capability of the LiMn2O4 nanowires.

Cycling performance of the as-synthesized LiMn2O4 nanowires electrodes at (a) 500 mA g−1 and (b) various current densities ranged from 100 to 2000 mA g−1. (c) Charge and discharge voltage profiles at 200 mA g−1 and (d) rate performance at current densities between 500 and 1500 mA g−1 of the as-fabricated full battery based on FeS@TiO2 nanostructures anode and LiMn2O4 nanowires cathode.

To demonstrate the real contribution of the FeS@TiO2 nanostructures electrode to the assembled LiMn2O4/FeS@TiO2 full battery, the over-capacity of the LiMn2O4 nanowires was adopted. Figure 6c shows the charge/discharge voltage profiles of the as-fabricated full battery. As expected from the operating voltages of the FeS@TiO2 nanostructures and LiMn2O4 nanowires, their combination produces a battery with an operating voltage of 2.2 V and the discharge capacity of the battery is 520 mAh g−1 with a coulombic efficiency of 98% at 200 mA g−1. The rate performance of the full battery was further inspected, as illustrated in Figure 6d. Remarkably, an acceptable capacity of 350 and 170 mAh g−1 at 500 and 1500 mA g−1, respectively, during the 5th cycle could be achieved, which are comparable with the rate performance of practical graphite-based full battery, although the rate capacity at high current density is still need to be improved. Further investigations are on-going to improve the capacity of the full cell at high discharge rates to meet the demand of electronic device for high energy density.

Discussion

In order to gain better understanding on the enhanced electrochemical performances of the FeS@TiO2 nanostructures electrodes, we have performed CV measurements to investigate the kinetics of lithium ion insertion/extraction at the electrode/electrolyte interface and rate of lithium diffusion in the film. It is known that the change in peak shape with sweep rate reflects the kinetics of lithium insertion/extraction at the electrode/electrolyte interface and rate of lithium diffusion in the film29. Figures 7a and 7b show the CV curves of the pristine FeS and the FeS@TiO2 nanostructures electrodes recorded at scan rates of 0.1–0.8 mV s−1 in the voltage range of 0.01–3.0 V after 5 th, 10 th, 15 th and 20 th cycles. As the scan rates increase, the cathodic and anodic peaks moved to lower and higher potential, respectively, with the increase of the magnitude of the peak currents. Furthermore, the peak currents of the FeS@TiO2 nanostructures electrodes are higher than those of the pristine FeS electrodes, indicating the incorporation of TiO2 render the composite electrodes much faster lithium diffusion and much higher lithium storage capacity. As evidenced in Figures 7c and 7d, linear correlation was established between the anodic/cathodic peak currents and the square roots of scan rates for both Peak 1 and 2, which suggests diffusion-limited reactions30. In this kind of reaction, the peak currents and scan rates follow the Randles-Sevcik equation31:

Where Ip is the peak current; n is the number of transfer electrons; A is the surface area of electrodes; D is the diffusion coefficient; υ is the scan rate and ΔC0 is the concentration of reaction. It is worth noting that the slops for peak 1 and peak 2 on the FeS@TiO2 nanostructures were higher than those for the FeS system, revealing that the combination of TiO2 into the FeS nanostructures is benefit to improve the lithium diffusion coefficient, resulting the enhanced electrochemical performance for lithium storage.

To gain insight into the prominent electrochemical properties of the FeS@TiO2 nanostructures with respect to the FeS electrode, we also take the electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) measurements as shown in Figure 8. The equivalent circuit model of the studied system is also shown in Figure 8 inset to represent the internal resistance of the test battery according to literature32,33. The high-frequency semicircle corresponds to the contact resistance (Rf) and constant phase element of the SEI film (CPE1), the semicircle in the medium-frequency region is assigned to the charge-transfer impedance (Rct) and constant phase element of electrode/electrolyte interface (CPE2) and Zw is associated with the Warburg impedance corresponding to the lithium-diffusion process. Clearly, the diameter of the semicircle for the FeS@TiO2 nanostructures electrode in the high-medium frequency regain is much smaller than that of the pristine FeS electrode, revealing that the FeS@TiO2 nanostructures electrode possess lower contact and charge-transfer impedances. This result also validates that the introduced TiO2 can improve the electrical conductivity of the overall electrode. Besides, from the low frequency inclined line, we can find that the lithium-diffusion process of the FeS@TiO2 nanostructures electrode is much easier than that of the FeS electrode, further conforming that the coated TiO2 benefit the lithium-diffusion of the composite electrode. The kinetic differences of FeS and FeS@TiO2 electrodes were further investigated by modeling AC impedence spectra based on the modified equivalent circuit34,35. The fitted impedence parameters are listed in Table 1. It can be seen that the SEI film resistance Rf and charge-transfer resistance Rct of the FeS@TiO2 electrode are 84.9 Ω and 109 Ω, which are significantly lower than those of the pristine FeS (140.2 Ω and 169.7 Ω). This fact once again confirms that the introduction of TiO2 can preserve the high conductivity of the FeS@TiO2 composite electrode and greatly enhance rapid electron transport during the electrochemical lithium insertion/extraction reaction, resulting in significant improvement in the electrochemical performances.

In summary, we exhibited a novel one-dimensional anatase TiO2 modified FeS nanostructure composed of 2D FeS nanosheets and TiO2 nanoparticles. The composite electrodes show a capacity of 510 mAh g−1 after 100 cycles, much higher than that of the pristine FeS nanostructures (266 mAh g−1) at a current density of 200 mA g−1. Meanwhile, the integrated electrodes exhibit enhanced rate capability at current densities ranged from 100 to 4000 mA g−1 and long-term cycling stability with little performance degradation even after 500 discharge/charge cycles at current density of 400 mA g−1. The superior electrochemical performances of the composite nanostructures can be ascribed to the incorporation of anatase TiO2, which, to some extent, improve the conductively of the integrated electrodes and enhance the kinetics of lithium insertion/extraction at the electrode/electrolyte interface and rate of lithium diffusion in the film. The carbon-free conducting nanocoated electrodes would open up new opportunities in the development of high performance next-generation lithium-ion batteries and other energy conversion and storage devices used for alternative and sustainable energy.

Methods

Preparation of FeS and FeS@TiO2 nanostructures

FeS nanostructures were prepared by using solvothermal method, similar to the literature except the anneal temperature21. Briefly, FeCl2·4H2O (1.18 g) was mixed with CH3CSNH2 (thioacetamide, 0.9 g) in Teflon-lined steel autoclave and 40 mL ethylenediamine was add to it. The container was sealed and heated to 180°C for 4 days under solvothermal conditions to obtain organic-inorganic composite nanowires. FeS nanostructures were obtained by annealing the composite products at 500°C for 60 min under a flow of N2 (200 sccm). To obtain FeS@TiO2 nanostructures, the composite products were first immersed in the TiCl4 solution (40 mM) at 70°C for 30 min and then annealed at 500°C for 60 min under a flow of N2 (200 sccm).

Fabrication of LiMn2O4 nanowires

LiMn2O4 nanowires were fabricated via a solid state reaction of β-MnO2 nanowires and lithium hydroxide. The synthesis of β-MnO2 nanowires can be seen in our previous report36. Typically, manganese sulfate (0.338 g) and potassium chlorate (0.246 g) were dissolved in 25 mL of distilled water under vigorous stirring to form a homogeneous solution. The mixture was then transferred to a Teflon-lined stainless steel autoclave and kept in an oven at 200°C for 12 h. After being treated, the obtained β-MnO2 nanowires were collected and then mixed with lithium hydroxide with mole ratio of 1:0.55. After annealing at 750°C for 10 h in air, the LiMn2O4 nanowires were obtained.

Charactization

The phase purity of the products were characterized by X-ray powder diffraction (XRD) using an X-Ray diffractometer with Cu Kα radiation (λ = 0.15 nm). Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images and energy dispersive X-Ray spectroscopy (EDS) analyses were obtained using a Sirion 200 microscope. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and high-resolution TEM (HRTEM) observations were carried out on a Philips CM 200 instrument. X-Ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) spectra were performed on a VG Multilab 2000 system with a monochromatic aluminium anode X-ray source.

Electrochemical evaluation

The working electrodes were fabricated by coating a slurry containing 70 wt% active materials ( FeS or FeS@TiO2 nanostructures), 20 wt% acetylene black (Super-P) and 10 wt% polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) dissolved in N-methyl-2-pyrrolidinone onto a copper foil and dried at 80°C in vacuum for 12 h before pressing. Laboratory-made two-electrode CR2032 coin cells were assembled in an argon-filled glovebox using a pure lithium foil as the counter electrode. A separator membrane (Celgard 2300) was used to isolate the two electrodes. The electrolyte was 1 M LiPF6 dissolved in a mixture of ethylene carbonate (EC) and dimethyl carbonate (DMC) (v/v = 1:1). The coin cells were galvanostatically discharged/charged at different current densities between 0.01 and 3.00 V (vs. Li+/Li) by using a battery testing system (LAND, China). Cyclic voltammetry (CV) was measured on an electrochemical workstation (CHI 760D, CH Instruments Inc., Shanghai) and electrochemical impedance spectrometry in the frequency range of 100 kHz to 0.1 Hz at room temperature.

References

Arico, A. S., Bruce, P. G., Scrosati, B., Tarascon, J. & Schalkwijk, W. V. Nanostructured materials for advanced energy conversion and storage devices. Nat. Mater. 4, 366–377 (2005).

Guo, Y.-G., Hu, J.-S. & Wan, L.-J. Nanostructured Materials for Electrochemical Energy Conversion and Storage Devices. Adv. Mater. 20, 2878–2887 (2008).

Wang, H. et al. Graphene-wrapped sulfur particles as a rechargeable lithium-sulfur battery cathode material with high capacity and cycling stability. Nano Lett. 11, 2644–2647 (2011).

Lee, S., Cho, Y., Song, H.-K., Lee, K. T. & Cho, J. Carbon-coated single-crystal LiMn2O4 nanoparticle clusters as cathode material for high-energy and high-power lithium-ion batteries. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 51, 8748–8752 (2012).

Singh, N. et al. Paintable battery. Sci. Rep. 2, 481 (2012).

Ding, S., Chen, J. S. & Lou, X. W. One-Dimensional Hierarchical Structures Composed of Novel Metal Oxide Nanosheets on a Carbon Nanotube Backbone and Their Lithium-Storage Properties. Adv. Funct. Mater. 21, 4120–4125 (2011).

Wang, H. G., Ma, D. L., Huang, X. L., Huang, Y. & Zhang, X. B. General and controllable synthesis strategy of metal oxide/TiO2 hierarchical heterostructures with improved lithium-ion battery performance. Sci. Rep. 2, 481 (2012).

Wang, X. F. et al. Three-dimensional hierarchical GeSe2 nanostructures for high performance flexible all-solid-state supercapacitors. Adv. Mater. 25, 1479–1486 (2013).

Liu, J. & Liu, X.-W. Two-dimensional nanoarchitectures for lithium storage. Adv. Mater. 24, 4097–4111 (2012).

Xu, C. et al. Controlled soft-template synthesis of ultrathin C@FeS nanosheets with high-Li-storage performance. ACS Nano 6(6), 4713–4721 (2012).

Liu, H., Su, D. W., Wang, G. X. & Qiao, S. Z. An ordered mesoporous WS2 anode material with superior electrochemical performance for lithium ion batteries. J. Mater. Chem. 22, 17437–17440 (2012).

Yang, L. et al. Hierarchical MoS2/polyaniline nanowires with excellent electrochemical performance for lithium-ion batteries. Adv. Mater. 25, 1180–1184 (2013).

Xiao, J. et al. Electrochemically induced high capacity displacement reaction of PEO/MoS2/graphene nanocomposites with lithium. Adv. Funct. Mater. 21, 2840–2846 (2011).

Ji, L., Lin, Z., Alcoutlabi, M. & Zhang, X. Recent developments in nanostructured anode materials for rechargeable lithium-ion batteries. Energy Environ. Sci. 4, 2682–2699 (2011).

Kostov, S. et al. X-ray absorption fine structure studies of FeS cathodes in lithium polymer electrolyte batteries. Journal of Power Sources 81–82, 709–714 (1999).

Kim, Y. & Goodenough, J. B. Lithium insertion into transition-metal monosulfides: tuning the position of the metal 4 s band. J. Phys. Chem. C 112, 15060–15064 (2008).

Cheon, S. E. et al. Rechargeable litium sulphur battery II. Rate capacity and cycle characteristics. J. Electrochem. Soc. 150, A800–A805 (2003).

Ji, L. et al. Graphene oxide as a sulfur immobilizer in high performance lithium/sulfur cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 18522–18525 (2011).

Ji, L. et al. Porous carbon nanofiber-sulfur composite electrodes for lithium/sulfur cells. Energy Environ. Sci. 4, 5053–5059 (2011).

Wang, Y.-Q. et al. Rutile-TiO2 nanocoating for a high-rate li2Ti5O12 anode of lithium-ion battery. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 7874–7879 (2012).

Nath, M., Choudhury, A., Kundu, A. & Rao, C. N. R. Synthesis and characterization of magnetic iron sulfide nanowires. Adv. Mater. 15, 2098–2101 (2003).

Wang, W. Z. et al. High-yield synthesis of single-crystalline antimony telluride hexagonal nanoplates using a solvothermal approach. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127, 13792–13793 (2005).

Saadat, S. et al. Template-free electrochemical deposition of interconnected ZnSb nanoflakes for li-ion battery anodes. Chem. Mater. 23, 1032–1038 (2011).

Luo, Y. S. et al. Seed-assisted synthesis of highly ordered TiO2@Fe2O3 core/shell arrays on carbon textiles for lithium-ion battery applications. Energy Environ. Sci. 5, 6559–6566 (2012).

Yang, S. H. & Quinn, C. H. Chemical, structural and electrochemical comparison of natural and synthetic FeS2 pyrite in lithium cells. Electrochim. Acta. 46, 2613–2621 (2001).

Wu, B., Song, H., Zhou, J. S. & Chen, X. H. Iron sulphide-embedded carbon microsphere anode material with high-rate performance for lithium-ion batteries. Chem. Commun. 47, 8653–8655 (2011).

Fong, R., Jones, C. H. W. & Dahn, J. R. A study of pyrite-based cathodes for ambient temperature lithium batteries by in situ Fe Mossbauer spectroscopy. J. Power Sources, 26, 333–339 (1989).

Hosono, E., Kudo, T., Honma, I., Matsuda, H. & Zhou, H. S. Synthesis of single crystalline spine LiMn2O4 nanowires for a lithium ion battery with high power density. Nano Lett. 9(3), 1045–1051 (2009).

Rougier, A., Striebel, K. A., Wen, S. J. & Cairns, E. J. Cyclic voltammetry of pulsed laser deposited LixMn2O4 thin films. J. Electrochem. Soc. 145, 2975–2980 (1998).

Zhang, B. et al. Exceptional electrochemical performance of freestanding electrospun carbon nanofiber anodes containing ultrafine SnOx particles. Energy Environ. Sci. 5, 9895–9902 (2012).

Das, S. R., Majumder, S. B. & Katiyar, R. S. Kinetic analysis of the Li+ ion intercalation behavior of solution derived nano-crystalline lithium manganite thin films. J. Power Sources. 139, 261–268 (2005).

Yang, S., Feng, X., Ivanovici, S. & Müllen, K. Fabrication of Graphene-encapsulated oxide nanoparticles: towards high-performance anode materials for lithium storage. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 49, 8408–8411 (2010).

Chang, K. & Chen, W. X. L-Cysteine-assisted synthesis of layered MoS2/graphene composites with excellent electrochemical performances for lithium ion batteries. ACS Nano 28, 4720–4728 (2011).

Yang, S. B. et al. Nanographene-constructed hollow carbon spheres and their favorable electroactivity with respect to lithium storage. Adv. Mater. 22, 838–842 (2010).

Yang, S. B., Song, H. H. & Chen, X. H. Electrochemical performance of expanded mesocarbon microbeads as anode material for lithium-ion batteries. Electrochem. Commun. 8, 137–142 (2006).

Wang, L. J. et al. Facile synthesis and electrochemical properties of CoMn2O4 anodes for high capacity lithium-ion batteries. J. Mater. Chem. A 1, 2139–2143 (2013).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the support from the National Natural Science Foundation (21001046, 51002059, 91123008), the 973 Program of China (2011CB933300) and the Program for New Century Excellent Talents of the University in China (grant no. NCET-11-0179). We thank the Analytical and Testing Center of Huazhong University Science & Technology and the Center of Micro-Fabrication and Characterization (CMFC) of WNLO for the samples measurements.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.F.W., D.C. and G.Z.S. devised the original concept, designed the experiment, discussed the interpretation of results and co-wrote the paper. X.F.W., Q.Y.X. and L.J.W. performed the experiments. B.L. and T.L. analysed the dates. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information

supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, X., Xiang, Q., Liu, B. et al. TiO2 modified FeS Nanostructures with Enhanced Electrochemical Performance for Lithium-Ion Batteries. Sci Rep 3, 2007 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep02007

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep02007

This article is cited by

-

0D–2D Schottky heterostructure coupling of FeS nanosheets and Co9S8 nanoparticles for long-term industrial-level water oxidation

Nano Research (2023)

-

Recent progress in Ti-based nanocomposite anodes for lithium ion batteries

Journal of Advanced Ceramics (2019)

-

Freestanding Three-Dimensional CuO/NiO Core–Shell Nanowire Arrays as High-Performance Lithium-Ion Battery Anode

Scientific Reports (2018)

-

Amine-assisted synthesis of FeS@N-C porous nanowires for highly reversible lithium storage

Nano Research (2018)

-

Silicon and Carbon Nanocomposite Spheres with Enhanced Electrochemical Performance for Full Cell Lithium Ion Batteries

Scientific Reports (2017)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.