Abstract

Studies reveal that there exists much interaction and communication between bacterial cells, with parts of these social behaviors depending on cell–cell contacts. The cell–cell contact has proved to be crucial for determining various biochemical processes. However, for cell culture with relatively low cell concentration, it is difficult to precisely control and retain the contact of a small group of cells. Particularly, the retaining of cell–cell contact is difficult when flows occur in the medium. Here, we report an optofluidic method for realization and retaining of Escherichia coli cell–cell contact in a microfluidic channel using an abrupt tapered optical fibre. The contact process is based on launching a 980-nm wavelength laser into the fibre, E. coli cells were trapped onto the fibre tip one after another, retaining cell–cell contact and forming a highly organized cell chain. The formed chains further show the ability as bio-optical waveguides.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Bacteria in nature display complex multicellular social behaviors, such as interaction and communication with one another, allowing them to sense, integrate and modulate their behavior in response to environmental fluctuation1,2,3,4,5. The interaction and communication between bacterial cells can be divided into those relying on diffusible factors1,2,3,5,6 and those depending on cell–cell contacts7,8. The cell–cell contact has proved to be crucial for determining the suppression of neoplastic phenotype9, activating microRNA biogenesis10, preparing spheroids composed of primary cancer cells11, etc. Cell contact-dependent interactions are also widespread among bacteria12 as elementary processes of cargo delivery and cell-to-cell signaling. Cell–cell contact, as a most straightforward way of interaction between cell individuals, is a key process to understand the relationship between cell differentiation and communication. It is, however, very hard to rule out the external effects such as cell paracrine or nutrient concentrations in the study of cell–cell contact in a large cluster of cells, unless employing some special techniques, such as well-designed patterned materials13, to localize a few cells. However, this cell–cell contact is generally realized in stationary medium, it will become difficult to retain this contact when realized in a flowing medium. To improve the precision and selectivity of cell–cell contact and meanwhile retaining this contact in such a flowing medium for further biochemical analysis, a technique, which can be applied to flexibly manipulate cells and precisely analyze their biochemical properties, is highly desired. Among the candidates for cell manipulation and analysis techniques, optofluidics can be considered as a preferable one.

By bridging optics and microfluidics, optofluidics has emerged as a dynamic and versatile platform, which enables simultaneous delivery of light and fluids with high precision, constantly delivering new insights and discoveries in a wide range of applications14,15. Particularly, optofluidics is well-suited for biochemical applications16,17,18, such as biomolecule sensing and analysis16, manipulation and transportation of living cells at controlled speeds and directions17,18, etc. The key technique for cells manipulation in an optofluidic platform is optical trapping. Since its birth19, optical trapping has been applied in localizing and manipulating cells with focusing laser beams20,21, known as optical tweezers (OTs). To avoid the bulky structure and inflexibility of focusing objective and optical system in OTs, optical fibres are applied to trap and manipulate different objects22,23,24,25,26,27,28, such as cells22,23,24,25,26,27. A single cell can be trapped22, deformed23, or stretched24 using two counter-aligned optical fibres (TCFs) and transported25,26 or arranged25,27 using a single gradually tapered optical fibre (GTF), exhibiting high stiffness. Compared to the TCFs, GTF exhibits higher three-dimensional flexibility in manipulation. Due to its very small size, GTF tip, which provides very high optical intensity and strong optical force to trap cells, is totally occupied by a single cell with a larger size than the tip size during the trapping process. This often limits the trapping capability of a tapered fibre to only a single cell. Generally, optical methods, such as OTs20,21, TCFs22,23,24 and GTF25,26,27, are limited to single cell trapping and manipulation. However, stable trapping of multiple particles and cells, particularly, with organized alignment29, is of great importance in a wide variety of applications, such as cell–cell contact realization and retaining7,11,13. In addition, most cells trapped with GTF are limited to eukaryotic cells. However, trapping of smaller bacterial cells, such as E. coli cells, which are key candidates for studying cell–cell contact interaction and communication, is challenging. Compared to GTF, abrupt tapered optical fiber (ATF) will be more hopeful for stable trapping of small bacterial cells because it can minimize optical loss in the non-tapered region and thus can maximize optical intensity and optical force at the fiber tip. Therefore, in this work, we report realization and retaining of cell–cell contact using an ATF by launching a laser beam at 980 nm wavelength into the fiber placed in a microfluidic channel. E. coli cells, which own the optical properties of high transparency and larger refractive index (n = 1.39) than that of the surrounding (e.g. water, n = 1.33), were used as cell samples. These cells can form an extension of the ATF and consequently trap their compatriots, which greatly expand the trapping capability of the ATF. With the laser power varying from 13 to 85 mW, E. coli cell chains with trapped cell numbers from 2 to 17 were formed at the fibre tip, which represents the optofluidic realization and retaining of highly organized bacteria cell–cell contact. The formed cell chains were further used as bio-optical waveguides, offering a seamless interface between optical and biological worlds.

Results

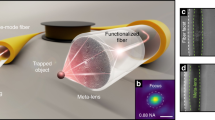

Figure 1 schematically shows optofluidic realization and retaining of E. coli cell–cell contact in a microfluidic channel (see Methods for fabrication). An ATF (see Methods for fabrication and Fig. S1 for details) was placed in the microfluidic channel with a flowing E. coli suspension (see Methods for preparation). With a laser at 980 nm wavelength (with little photodamage to E. coli cells in optical traps30) launched into the ATF, E. coli cells delivered by the flowing suspension were trapped and connected one after another, forming a bacteria cell chain.

Stable trapping and orientation of a single E. coli cell

To better understand the mechanism of E. coli cell–cell contact, stable optical trapping of a single E. coli cell was performed (Fig. 2a). A flowing suspension was served to deliver the E. coli cells to the ATF. To get high delivery efficiency, the flow velocity of the E. coli cell suspension in the microfluidic channel was 16 μm/s. By launching a laser at 980 nm wavelength with an input optical power of 30 mW into the fibre, a single E. coli cell delivered by the flowing suspension was trapped. Interestingly, it was found that, an E. coli cell with any arbitrary azimuthal angle θ (the angle between the long axis of the E. coli and the extension of the ATF central axis) was trapped with a fixed orientation in the final stable state, i.e., θ = 0°. For example, as shown in Fig. 2a, at ton = 0 s (laser on, Fig. 2a1), the E. coli with θ = 83° was delivered toward the ATF by the flowing suspension with a distance of 7.9 μm to the ATF tip. Once trapped, the E. coli was gradually rotated from θ = 83° to 0° in 0.7 s (Fig. 2a2–a4). Once laser was off, the trapped E. coli was flowed away by the flowing suspension (Fig. 2a5 and a6).

Optical trapping of a single E. coli cell in the micofluidic channel.

(a) Optical microscope images of the trapping and orientation process of a single E. coli cell. Blue, red and yellow arrows indicate flow velocity (16 μm/s), the input laser with an optical power of 30 mW and the orientation of the E. coli, respectively. (b) Calculated torque acting on an E. coli cell as a function of azimuthal angle θ. Inset I shows the calculation model, the E. coli is orientated with θ to the ATF central axis, point i indicates the arbitrary interaction point with a position vector ri pointed from the central point of the E. coli cell. Inset II shows the most stable trapping orientation with θ = 0. (c) Calculated trapping force (FT) exerted on a single E. coli cell as a function of distance (D) between the cell and the fiber tip. Inset I schematically shows the calculation model and inset II shows the simulated energy density distribution around the trapped E. coli cell.

To explain the trapping and orientation ability of the ATF, a finite-element method was used to simulate distribution of optical energy density, which is related to the trapping ability, output from the ATF (Fig. S2). In the simulation, the E. coli cell was assumed to be a rod (diameter: 700 nm, length: 2 μm) with hemispherical caps. The refractive indices are 1.44, 1.39 and 1.33 for the ATF, E. coli cell and water, respectively at the wavelength of 980 nm. Simulation results show that, benefiting from the abrupt tapered shape, energy density is highly concentrated at the tip of the fibre, which can exert a large gradient force on the cell near the tip and thus the cell will be stably trapped. By integrating the time-independent Maxwell stress tensor 〈TM〉 on a surface enclosing the E. coli cell, the optical force (i.e. electromagnetic force, FEM) exerted on the cell can be calculated by31,32

where n is the surface normal vector.

The orientation of the trapped E. coli cell can be decided by the restoring torque (T) which is defined as33

where dFEM i is the electromagnetic force element at the interaction point i and ri is the position vector pointing from the central point of the E. coli cell to the interaction point where dFEM i is generated (inset I of Fig. 2b shows the calculation model). Figure 2b shows the calculated restoring torque acting on the E. coli cell with an azimuthal angle θ to the ATF central axis. It can be seen that the torque is 0 with θ = 0 (inset II), indicating the most stable orientation for the trapped E. coli cell. And thus, the E. coli was finally trapped with its long axis along the central axis of the ATF as shown in Fig. 2a.

To show the trapping ability of the ATF for an E. coli cell with different distances to the ATF tip, as an example, the FEM exerted on an E. coli cell with different distance (D) to the ATF tip at the input optical power of 30 mW was calculated, as shown in Fig. 2c. In the experiment, the azimuthal angel (θ) of the E. coli cells delivered toward the tip was varied from −90° to 90°, therefore, in the calculation, we take θ = 0 as a particular datum (inset I). Because FEM is directed to the fibre, thus it acts as a trapping force (FT). It can be seen that, for D < 8 μm, FT > 2 pN. Therefore, the E. coli cell will be stably trapped by FT. Inset II of Figure 2c shows the simulated energy density distribution around the trapped E. coli cell.

Cell-cell contact realization

To demonstrate stable trapping and connecting of multiple E. coli cells with highly organized orientation, i.e., realization and retaining of E. coli cell–cell contact, the 980-nm wavelength laser with an optical power of 30 mW was launched into the ATF (Fig. 3a). When cell I delivered by the flowing suspension with a flow velocity of 3 μm/s was near the ATF tip (t = 0 s, Fig. 3a1), it was then trapped by optical trapping force. Interestingly, when cell II was delivered toward the ATF (t = 11 s, Fig. 3a2), it was also trapped and connected to cell I (t = 13 s, Fig. 3a3), realizing cell–cell contact with cell number of N = 2. Similarly, the delivered cells III and IV were trapped and connected to the former cell at t = 20 and 40 s, realizing cell–cell contact with N = 3 and 4 as shown in Fig. 3a4 and a5, respectively. Remarkably, all the trapped and connected cells were aligned with the same orientation, i.e., with their long axis along the ATF central axis. The reason is that the restoring torque is zero when the long axis of the cell is along the ATF axis, making this orientation a most stable one. This is similar to that of trapping a single E. coli cell analyzed in Fig. 2. Further experiment shows that trapping stability of the tail cell in the formed cell chain was decreased with increasing flow velocity, but can be trapped back immediately once decreasing the flow velocity (Fig. 3a6–a8). The realized cell–cell contact was retained in a stable state and the formed cell chain was not released until the laser was turned off (t = 70 s, Fig. 3a9). Moreover, highly organized E. coli cell chains (and cell–cell contact) with different cell numbers were formed by increasing the input optical powers while remaining the flow velocity at 3 μm/s. Figure 3b shows the formed cell chains with cell numbers of N = 3, 8, 11, 14 and 17 (respective chain lengths of L = 6.6, 16.4, 21.4, 27.8 and 34.6 μm) at input optical powers of P = 20, 44, 56, 68 and 83 mW, respectively. Examples of other formed cell chains with different numbers and lengths at different input optical powers are shown in Fig. S3. It should be noted that there are some other cells around the trapped cell chain in Fig. 3b and Fig. S3. However, these cells cannot be trapped and will move to other places due to the Brownian motion of the E. coli cells, thus these cells make little influence on the trapped cell chains. Figure 3c shows the relation of connected largest E. coli cell numbers and chain length in a stable cell chain versus input optical power. It can be seen that the contacting ability is increased with the increasing input optical power. To realize cell–cell contact and form cell chains with larger cell numbers, one should only increase the optical power launched into the ATF. Details of realization the E. coli cell–cell contact and forming cell chains using this optofluidic method is shown in Video S1.

Realization and retaining of E. coli cell–cell contact in the micofluidic channel.

(a) Optical microscope images of the trapping and forming process of a cell-cell contact chain by launching the 980-nm wavelength light with a power of 30 mW (red arrow indicated) into the fiber. The blue arrows indicate the direction of flowing suspension with a velocity of 3 μm/s. (b) E. coli cell chains formed with different cell numbers N = 3, 8, 11, 14 and 17 at different input optical powers P = 20, 44, 56, 68 and 83 mW, respectively. L indicates respective chain length. Insets schematically show the corresponding E. coli cell chains. (c) Largest E. coli cell number (N) in a stable formed chain and corresponding chain length (L) as a function of input optical power P. (d) Cell growth and division after trapped and contacted. Red, blue and yellow arrows indicate the launched laser, the contact between adjacent cells and the division sites of cells, respectively.

To extend this method to the potential usage of cell studies, additional experiments were carried out to test the cell viability and proliferation after cell chain formation and cell-cell contact realization. To make sure the E. coli cells in a good growing and multiplying condition, cells in the logarithmic phase were chosen and diluted with liquid culture medium (Lysogeny broth, LB). To avoid the influence of water fluctuation induced by the flowing medium, the cell growth and division observation was carried out in stationary culture medium. Figure 3d, as an example, shows growth and division of cells after cells A and B were trapped and contacted with an optical power of 30 mW launched into the ATF. At t = 0 min, the lengths of the cells A and B are 2.7 and 2.5 μm, respectively. At t = 20 min, the cells A and B grew to 3.7 and 3.1 μm, respectively. At t = 30 min, the respective lengths of the cells A and B are 3.9 and 3.3 μm. At t = 40 min, the two cells were divided into four cells (cells A1, A2, B1 and B2) with respective lengths of 2.1, 1.9, 1.8 and 1.6 μm. At t = 50 min, the lengths of the four cells are increased to 2.7, 2.0, 2.0 and 1.9 μm, respectively. These results show that the E. coli cells in the formed cell chains with cell-cell contact using this method have a good viability and proliferation ability.

Cell-cell contact retaining

To demonstrate the retaining ability of the realized bacteria cell–cell contact, moving of formed cell chains were further realized by moving the ATF in the microfluidic channel. To realize a stable moving of the chain and decrease water fluctuation, a flow velocity of 3 μm/s was chosen. Figure 4, as an example, shows the moving of a chain with N = 5 and L = 10.4 μm formed at an input optical power P = 32 mW. Figure 4a shows the initial location of the cell chain. By moving the ATF in −y direction, the chain was simultaneously moved with 3.2 μm (Fig. 4b), 4.6 μm (Fig. 4c) and 6.1 μm (Fig. 4d) at tM = 2, 3 and 4 s, respectively. In the moving process, the formed cell chain was kept stable, retaining the realized cell–cell contact. Further experiments show that two-dimensional (2D) moving of a cell chain can also be realized (see Fig. S4). These results show that the formed cell chain is stable and the cell-cell contact can be retained. To show the stability of the cell chain for a long time, additional experiments have been carried out to maintain the formed cell chain. In the experiment, a formed cell chain with a length of about 25 μm was used as an example. Experimental results show that the chain can be maintained stable (if the ATF is kept stable) for about 4 hours on condition that the flow velocity is smaller than 5 μm/s which caused little water fluctuation.

Optical microscope images of flexible moving of a cell chain and light propagation along a cell chain.

(a–d) Flexible moving of a cell chain, the chain was formed by connecting five E. coli cells at an input optical power of 32 mW. Blue arrows indicate the flow velocity (3 μm/s). Insets schematically show the original location of the chain. (e,f) Light propagation along a cell chain. The slanted red arrow indicates the output 644-nm light at the output of the chain.

Waveguiding ability

Generally, most of the optical waveguides are fabricated with materials which lack biocompatibility. However, the rapid progresses in biological and biomedical applications with optical interfaces have motivated an ever-increasing demand for biocompatible photonic components. To extend this realized cell–cell contact and formed cell chains to an interdisciplinary function and connect the optical and biological worlds seamlessly, we further demonstrate the waveguiding ability of the formed cell chains. After formation of the chains, a laser at 644-nm wavelength (optical power: 10 μW) was coupled into the ATF using an optical coupler (keeping the 980-nm laser launched). Figure 4e, as an example, shows the formed cell chain (length: L = 33.2 μm, contacted cell number: N = 17) at a flow velocity of about 3 μm/s with a 980-nm wavelength laser (85 mW) launched into the ATF. With the 644-nm laser launched into the ATF, obvious light propagation along the formed cell chain was observed (Fig. 4f). The dynamic propagating of the 644-nm wavelength laser along the formed cell chain is shown in Video S2. This phenomenon indicates that the formed cell chains can be used as bio-optical waveguides. The importance of these bio-optical waveguide is that it is highly biocompatible, because the waveguide is directly formed with cells, rather than the inorganic materials. However, the limitation of this waveguide is that it can only be used in liquid environments.

Simulation and explanation

To explain the realization and retaining phenomena of highly organized bacteria cell–cell contact, simulations on optical energy density distribution and calculation on optical force were carried out by finite-element method. Figure 5a shows energy density distribution of four chains with cell numbers of N = 2, 5, 10 and 20, respectively at an input optical power normalized to 1 W (see Fig. S5 for more examples). It can be seen that light was highly confined inside the cells and propagated along the cell chain. This is because the connected E. coli cells have larger refractive index than that of the surrounding (water). In other words, the cell chain makes the ATF tip extended and consequently more cells were trapped. This greatly expands the trapping capability of the ATF. Figure 5b shows the calculated optical force exerted on the last E. coli cell in the chain by using Eq. (1). Calculation results show that, all the optical force exerted on the tail cells of chains with different cell numbers is directed to the ATF, thus this optical force is a trapping force (FT). As a result, the cells can be trapped together, realizing cell–cell contact. The cell chain formation principle is that: first, a trapping force, which was induced by the gradient of the highly concentrated light intensity at the ATF tip, exerts on the E. coli cell near the ATF tip. Once the cell is trapped (Fig. 2). Light will be propagated along the trapped cell. Light intensity gradient also exists at the end of the trapped cell and this gradient can further exert a trapping force on the second coming cell to trap and connect it to the former cell. Similarly, light can then propagate along the trapped cells and light intensity gradient exists at the end of the trapped cells. The trapped and contacted cells serve as an extension of the fibre and the light intensity gradient is shifted from the fibre tip to the end of the trapped cells. This intensity gradient can exert trapping force to the coming cells, these cells can then be trapped and connected to the former cells one by one, forming a cell chain. Interestingly, FT is firstly decreased from 118.5 to 62 pN/W as N is increased from 2 to 11 and then increased from 62 to 96.2 pN/W as N is increased from 11 to 14 and finally gradually decreased. This phenomenon is resulted from the redistribution of light as N is increased, intuitional example can be seen from the variation of energy density at the 7th, 12th and 15th cells in the formed chain with N = 20 (Fig. 5a). Actually, resulting from the low absorptivity of 980-nm wavelength light by the E. coli cells, the contacted cells with hemispherical caps act as ordered arrayed microlens and light irradiated on them will be sequentially focused and/or diverged, resulting in light intensity (and thus optical force) variation along the cells. The optical force (Fy) exerted on a cell beside the ATF axis in y direction can also be calculated using Eq. (1). By integrating Fy with distance along y direction, the trapping potential for the cell trapped at the ATF axis was calculated and shown in Fig. 5b. Details of the potential calculation are shown in Fig. S6. The absolute value of the potential for cells along the ATF axis is larger than 1.0 × 104 KBT/W, this large trapping potential further demonstrate the trapping and realization ability of the cell–cell contact with the ATF.

Simulation and calculation results for cell–cell contact and formed E. coli cell chains at an input optical power normalized to 1 W.

(a) Simulated energy density distribution for E. coli cell chains with cell numbers (N) of 2, 5, 10 and 20.(b) Calculated trapping force (FT) and trapping potential exerted on the last E. coli cell in the chain as a function of cell number (N). Inset schematically shows the model used in the simulation and calculation.

Discussion

Simulation and calculation results give an intuitional explanation for the highly organized cell–cell contact realization and retaining. Further experimental results show that, the retaining of cell–cell contact and the chain stability using this optofluidic method were influenced by the flow velocity. To show the influence of flow velocity on the stability of the formed cell chains, experiments with flowing suspension at different flow velocities were carried out when cell chains with different lengths were formed at different optical powers. Figure 6 shows the critical flow velocity (Vf0) for chains with different lengths. Each data of the length represents the largest length of a stable chain formed at each specific optical power as shown in Fig. 3(c). It can be seen that Vf0 is decreased with chain length, thus for a longer chain, the chain can stay stable with a smaller flow velocity. The chain can only stay stable when the flow velocity is smaller than Vf0. For each chain, when the flow velocity was larger than Vf0, the chain will be collapsed due to the water fluctuation induced by the flow. In this case, the cell–cell contact is invalid. In addition, although the cells in a chain experience both optical and fluidic forces, the chain formation is not relied on the fluidic force. To verify that the chain formation is only resulted from optical force, additional experiments were carried out. In the experiments, the flow was stopped and a formed cell chain was moved to and fro in transverse direction by moving the fibre (Video S3). In the moving process, the chain was kept stable and there was no loss of trapped cell numbers. Thus the fluidic flow simply serves to deliver the cells to the ATF. Further experiments show that the ATF, which can be used to realize multiple cell–cell contact, is highly reproducible. Different ATFs were fabricated using the same fabrication method to realize the cell–cell contact (see Fig. S7). In addition, for the same ATF, it is highly reusable and can be used for more than 10 times, while the cell-cell contact realization and retaining ability is not decreased. For practical application of this method in cell-cell contact study, the temperature distribution along the trapped cell alignment direction is also important, because cells are sensitive to temperature. In the experiments, to make sure the cells in a suitable temperature condition, all the experiments were carried out at room temperature (about 25°C). During the experimental process, there was no obvious temperature influence to the trapped cells chains. In our experiments, the temperature increment (ΔT) is resulted from the water absorption of the 980 nm wavelength laser. Although ΔT along the cell chains cannot be directly measured, it can be estimated from the simulation results34. Details of the ΔT estimation and calculation are shown in Fig. S8 (Supplementary Information). Calculation results show that the temperature increment after the trapping is within suitable temperature range for the E. coli survival and proliferation35.

Critical flow velocity (Vf0) as a function of cell chain length (L).

Each data of the length represents the longest length of a stable chain formed at each specific optical power as shown in Fig. 3(c).

This optofluidic method enables realizing and retaining stable cell–cell contact and the controlling of the trapped cells number using an ATF. Although E. coli cells were used as the objects for realization and retaining of bacteria cell-cell contact, the method would also be effective for cells of other species with a high transparency for operating light and a larger refractive index than that of the surrounding medium. Using existing manufacturing techniques, ATF used in this work can be integrated into current lab-on-a-chip platforms for multiple cells manipulation and biomedical/biochemical analysis via highly organized cell–cell contact. The cell–cell contact and optical manipulation in this manner could pave the way of investigating signal transduction and communication between cells. This work opens up the possibility of retaining cell–cell contact of bacterial cells using optical forces and enables the study of signal transduction between highly organized cells. Moreover, it shows the ability of forming bio-optical waveguides with cells, which offers a seamless interface between optical and biological worlds. This method would bridge researches in optofluidics, optical manipulation, biophotonics and cell biology, providing great potential in future interdisciplinary fundamental and applied researches.

Methods

Fabrication of microfluidic channel

The channel was fabricated in a quartz plate using femtosecond (fs) laser writing. The writing system is based on a commercial available amplified fs laser (Spectra Physics, Hurricane-1K-X, pulse center wavelength: 800 nm). An objective (×100, NA = 0.73) was used to focus the pulsed laser onto the quartz plate. A transverse writing configuration was adopted and the quartz plate was translated by motorized stages in a direction perpendicular to the laser beam. The writing speed was set at 150 μm/s. After writing, the channel (width: 140 μm, depth: 125 μm) was polished by oxyhydrogen flame brushing.

Preparation of E. coli cell suspensions

The E. coli cells were grown at 37°C in Lysogeny broth (LB), washed in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) buffer and re-suspended in the PBS buffer (diluted with deionized water) to desired concentrations (E. coli cell density: ~1.5 × 105 #/mL). After preparation, the suspensions were injected into a micropump (KDS LEGATO 270) connected to the microfluidic channel.

Fabrication of ATF

The ATF was fabricated by drawing a commercial single-mode optical fiber (connector type: FC/PC, core diameter: 9 μm, cladding diameter: 125 μm, Corning Inc.) through a flame-heating technique. Before heating, the fiber was sheathed by a glass capillary (inner diameter: ~0.9 mm, wall thickness: ~0.1 mm, length: ~120 mm) which ensures the fabricated ATF straightly placed in the microfluidic channel. The fiber was firstly kept heating for about 100 s until reaching its melting point. Then, with a drawing speed at about 3 mm/s applied on the heating region, the fiber was broken with an abrupt tapered tip (Figure S1).

Description of experimental setup

A personal computer interfaced microscopy (Union, Hisomet II) with a charge-coupled device was used for real-time monitoring and image capture. The ATF was placed in the channel and a flowing E. coli suspension was transfused into the channel by a micropump. A 980-nm wavelength laser was coupled into an optical splitter (10% : 90%). The 10% optical power was connected to an optical power meter for measurement and the other 90% was launched into the ATF for E. coli trapping and manipulation.

References

Bassler, B. L. Small talk: cell-to-cell communication in bacteria. Cell 109, 421–424 (2002).

Waters, C. M. & Bassler, B. L. Quorum sensing: cell-to-cell communication in bacteria. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 21, 319–346 (2005).

Bassler, B. L. & Losick, R. Bacterially speaking. Cell 125, 237–246 (2006).

Keller, L. & Surette, M. G. Communication in bacteria: an ecological and evolutionary perspective. Nature Rev. Microbiol. 4, 249–258 (2006).

Bischofs, I. B., Hug, J. A., Liu, A. W., Wolf, D. M. & Arkin, A. P. Complexity in bacterial cell–cell communication: Quorum signal integration and subpopulation signaling in the Bacillus subtilis phosphorelay. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 6459–6464 (2009).

Dubey, G. P. & Ben-Yehuda, S. Intercellular nanotubes mediate bacterial communication. Cell 144, 590–600 (2011).

Kovacs, E. M. & Yap, A. S. Cell–cell contact: cooperating clusters of actin and cadherin. Curr. Biol. 18, R667–R669 (2008).

Krauss, R. S. Regulation of promyogenic signal transduction by cell–cell contact and adhesion. Exp. Cell Res. 316, 3042–3049 (2010).

Rubin, H. Cell–cell contact interactions conditionally determine suppression and selection of the neoplastic phenotype. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 105, 6215–6221 (2008).

Hwang, H. W., Wentzel, E. A. & Mendell, J. T. Cell–cell contact globally activates microRNA biogenesis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 7016–7021 (2009).

Kondo, J. et al. Retaining cell–cell contact enables preparation and culture of spheroids composed of pure primary cancer cells from colorectal cancer. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 6235–6240 (2011).

Konovalova, A. & Søgaard-Andersen, L. Close encounters: contact–dependent interactions in bacteria. Mol. Microbiol. 81, 297–301 (2011).

Tang, J., Peng, R. & Ding, J. The regulation of stem cell differentiation by cell-cell contact on micropatterned material surfaces. Biomaterials 31, 2470–2476 (2010).

Psaltis, D., Quake, S. R. & Yang, C. Developing optofluidic technology through the fusion of microfluidics and optics. Nature 442, 381–386 (2006).

Monat, C., Domachuk, P. & Eggleton, B. Integrated optofluidics: A new river of light. Nature Photon. 1, 106–114 (2007).

Fan, X. & White, I. M. Optofluidic microsystems for chemical and biological analysis. Nature Photon. 5, 591–597 (2011).

Schmidt, H. & Hawkins, A. R. The photonic integration of non-solid media using optofluidics. Nature Photon. 5, 598–604 (2011).

Liu, G. L., Kim, J., Lu, Y. & Lee, L. P. Optofluidic control using photothermal nanoparticles. Nature Mater. 5, 27–32 (2006).

Ashkin, A. Acceleration and trapping of particles by radiation pressure. Phys. Rev. Lett. 24, 156–159 (1970).

Grier, D. G. A revolution in optical manipulation. Nature 424, 810–816 (2003).

Dholakia, K., Reece, P. & Gu, M. Optical micromanipulation. Chem. Soc. Rev. 37, 42–55 (2008).

Wei, M., Yang, K., Karmenyan, A. & Chiou, A. Three-dimensional optical force field on a Chinese hamster ovary cell in a fiber-optical dual-beam trap. Opt. Express 14, 3056–3064 (2006).

Guck, J., Ananthakrishnan, R., Moon, T., Cunningham, C. & Käs, J. Optical deformability of soft biological dielectrics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 84, 5451–5454 (2000).

Franze, K. et al. Müller cells are living optical fibers in the vertebrate retina. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 104, 8287–8292 (2007).

Xin, H., Xu, R. & Li, B. Optical trapping, driving and arrangement of particles using a tapered fibre probe. Sci. Rep. 2, 818 (2012).

Mohanty, S. K., Mohanty, K. S. & Berns, M. W. Manipulation of mammalian cells using a single-fiber optical microbeam. J. Biomed. Opt. 13, 054049 (2008).

Hu, Z., Wang, J. & Liang, J. Manipulation and arrangement of biological and dielectric particles by a lensed fiber probe. Opt. Express 12, 4123–4128 (2004).

Mishra, Y. N., Ingle, N. & Mohanty, S. K. Trapping and two-photon fluorescence excitation of microscopic objects using ultrafast single-fiber optical tweezers. J. Biomed. Opt. 16, 105003 (2011).

Mohanty, S. K., Mohanty, K. S. & Berns, M. W. Organization of microscale objects using a microfabricated optical fiber. Opt. Lett. 33, 2155–2157 (2008).

Neuman, K. C., Chadd, E. H., Liou, G. F., Bergman, K. & Block, S. M. Characterization of photodamage to Escherichia coli in optical traps. Biophys. J. 77, 2856–2863 (1999).

Xin, H. & Li, B. Targeted delivery and controllable release of nanoparticles using a defect-decorated optical nanofiber. Opt. Express 19, 13285–13290 (2011).

Yang, A. H. J. & Erickson, D. Stability analysis of optofluidic transport on solid-core waveguiding structures. Nanotechnology 19, 045704 (2008).

Gauthier, R. Theoretical investigation of the optical trapping force and torque on cylindrical micro-objects. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 14, 3323–3333 (1997).

Xin, H., Lei, H., Zhang, Y., Li, X. & Li, B. Photothermal trapping of dielectric particles by optical fiber-ring. Opt. Express 19, 2711–2719 (2011).

Cooper, V. S., Bennett, A. F. & Lenski, R. E. Evolution of thermal dependence of growth rate of Escherichia coli populations during 20,000 generations in a constant environment. Evolution 55, 889–896 (2001).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 11274395, 61205165, 61007038 and 10974261) and the 2012 New Academic Researcher Award for Doctoral Candidates granted by Ministry of Education, China.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

B.L. supervised the project; H.X., Y.L. and H.Z. performed the experiments; H.X. performed the simulation and calculation; H.X., Y.Z., H.L. and B.L. discussed the results and wrote the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information

Video S1

Supplementary Information

Video S2

Supplementary Information

Video S3

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Xin, H., Zhang, Y., Lei, H. et al. Optofluidic realization and retaining of cell–cell contact using an abrupt tapered optical fibre. Sci Rep 3, 1993 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep01993

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep01993

This article is cited by

-

Biophotonic probes for bio-detection and imaging

Light: Science & Applications (2021)

-

Fiber-based optical trapping and manipulation

Frontiers of Optoelectronics (2019)

-

Optical Trapping and Manipulation Using Optical Fibers

Advanced Fiber Materials (2019)

-

Investigation of optical force on magnetic nanoparticles with magnetic-fluid-filled Fabry-Perot interferometer

Scientific Reports (2018)

-

Thermal gradient induced tweezers for the manipulation of particles and cells

Scientific Reports (2016)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.