Abstract

Rapid photobleaching of fluorescent proteins can limit their use in imaging applications. The underlying kinetics is multi-exponential and strongly depends on the local chromophore environment. The first, reversible, step may be attributed to a rotation around one of the two exocyclic C-C bonds bridging phenol and imidazolinone groups in the chromophore. However it is not clear how the protein environment controls this motion - either by steric hindrances or by modulating the electronic structure of the chromophore through electrostatic interactions. Here we study the first step of the photobleaching kinetics in 13 red fluorescent proteins (RFPs) with different chromophore environment and show that the associated rate strongly correlates with the bond length alternation (BLA) of the two bridge bonds. The sign of the BLA appears to determine which rotation is activated. Our results present experimental evidence for the dominance of electronic effects in the conformational dynamics of the RFP chromophore.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The genetically-encoded fluorescent proteins (FPs) are powerful tools for imaging in biology1. The prototypical green fluorescent protein (GFP) from the jellyfish Aequorea Victoria consists of an 11-stranded β-barrel surrounding the 4-(p-hydroxybenzylidene)imidazolidin-5-one chromophore, which is formed autocatalytically1. The red fluorescent protein (DsRed) from coral Discosoma sp.2 has a similar structure, but the chromophore is extended by a π-conjugated acylamine tail1, producing red-shifted absorption and fluorescence. DsRed and its monomeric mFruits variants3,4 are advantageous for deeper imaging because of better red light penetration through biological tissues. Unfortunately, the RFPs suffer from rapid photobleaching3,4. The corresponding rates strongly depend on chromophore environment3,4 and the mutations around the chromophore can result in improved photostability5.

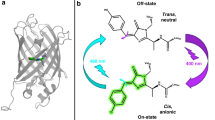

There is growing evidence that the key process of first, reversible step of photobleaching in different FPs is the cis-trans isomerization of the chromophore in the excited state, involving rotation around imidazolinone exocyclic bond (I-bond)6. In addition to I-bond isomerization, the rotation around phenyl (P-) bond can also be very efficient (sometimes barrierless and on picosecond timescale) in the isolated chromophore7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14. In DsRed and mFruits, fast reversible bleaching observed in bulk experiments15,16, fluorescence correlation17,18,19,20 and single molecule spectroscopy20,21 were also attributed to the conformational transformations of chromophore.

It is clear that the protein matrix inhibits the otherwise very fast (picosecond) I- or P-rotations in the excited state22, but the fundamental question of how this is accomplished, through steric hindrance or by controlling the electronic structure of the chromophore exocyclic bonds remains unanswered23.

Demachy and co-authors24 considered the steric hindrance effects on the rotational motion of the indole group of the cyan fluorescence protein (ECFP) chromophore by using molecular mechanics (MM) simulations and found that two non-polar residues (Ile167 and Val150) in a close proximity to the chromophore strongly limit its rotational freedom by short-range van der Waals repulsion. Maddalo and Zimmer25 calculated the equilibrium (static) values of P- and I-twisting angles in the ground electronic state of 38 different variants of GFP proteins using force field MM (with freely rotating P- and I-bonds in the absence of protein) and compared them to the corresponding experimental crystallographic data. Neither P- nor I-rotation calculated angles show any correlation with the measured ones. These studies suggest that although in some cases (such as ECFP with the bulky indole group in the chromophore) the steric and electrostatic force field effects are important; in others (like GFP family with smaller phenyl group) these effects are not dominant.

An alternative explanation, based on electronic effects, has been proposed12,13,23,26. The electrons are π-conjugated along the whole length of the chromophore. If the alternation of single and double bonds is definite, as in the neutral form of the GFP chromophore, the rotation will preferentially occur around single bond7,8,13. However, in the anionic form of the chromophore each bond in the bridge region has an intermediate order whose particular value can vary in response to local electric field of a particular mutant27. The rotation around one of the bonds would be less restricted if the bond character is closer to 1 and vice versa8,12,13,23,26, which means that the BLA between the P- and I-bonds in the excited state would be a controlling factor in selecting particular rotation coordinate and photoreaction rate. Using the apt expression of Olsen, Lamothe and Martinez13, “The isolated anion chromophore lies on the “razor's edge” between I-bond and P-bond torsion, allowing relatively minor environment and/or dynamical effects to tune between the two outcomes”.

There is an experimentally accessible parameter which reflects the environment-mediated variations of the BLA. This is the difference between the permanent dipole moments of the chromophore in the ground and excited states, Δμ. We have recently developed a purely optical method of measurement of this parameter, which uses the unique dependence of the two-photon absorption cross section on Δμ28,29. Here we show the strong correlation of the rate constant of the first, reversible step of photobleaching with the Δμ value, thus presenting experimental evidence for the dominance of electronic effects in conformational dynamics of red FPs.

Results

Photobleaching properties of the red FPs

To examine the role of the protein environment on the chromophore photoconversion dynamics, we selected a series of red FPs with the same chromophore, including DsRed2, its monomeric offspring mFruits and several new chimeras (see Methods).

The photobleaching kinetics of the proteins, monitored via the red fluorescence intensity decrease, is described in most cases by at least three exponents, in qualitative agreement with previous observations3,4,5,16. In partially bleached sample, some of the fluorescence signal recovers if the sample rests in the dark. Figure 1 shows the initial stage of photobleaching of DsRed2. After continuous bleaching of 50% of the initial signal the laser was strongly attenuated to a power level that does not cause any bleaching and the dark recovery was recorded. In this experiment 40% of initial signal was recovered. Depending on the protein and the depth of initial bleaching we observed 20–96% recovery.

Photobleaching kinetics of DsRed2 under continuous wave laser irradiation (532 nm, P = 1.1 W/cm2).

After 85 s of bleaching, the laser was strongly attenuated (to P = 0.03 W/cm2) and the dark recovery of signal was monitored. Red line shows the linear regression to the initial part of the bleaching. Inset shows a magnified part of the initial stage of the kinetics.

One can phenomenologically describe the photobleaching process with the following scheme:

where A is the initial state, B is the first intermediate state which can transform back to A either in dark or upon illumination, C is the next intermediate state, etc. Ri is the rate of the corresponding reaction, which generally contains both photo-induced and dark contributions. At the low excitation power conditions used here, the rate of the forward photo-induced conversion is

where P is the power density, ν is the photon frequency, h is the Planck's constant, σ1 is the one-photon absorption cross section at excitation wavelength, φp is the quantum yield of photoconversion, k1 is the rate constant for photoconversion, τ is the lifetime of the A excited state. We apply the method of initial rates which provides R1 as the derivative of the normalized kinetic curve at the initial stage, see Fig. 1.

For each protein we measured the dependence of R1 on incident power density (Fig 2). All of the dependences are linear, indicating that there is no saturation and only one-photon absorption process is involved. The φp values can be derived from linear regressions, since the σ1 are known (Supplementary Table). Finally, the monomolecular rates k1 = φp/τ were calculated (Supplementary Table). The k1 values vary remarkably (~40 times) throughout the series, suggesting crucial role of protein environment.

Two-form two-state model. Relation between Δμ and BLA

To correlate the bond length alternation between the P- and I-bonds with Δμ, we consider a simple two-form two-state (2F2S) model, previously developed for resonating charge-transfer molecules30,31,32. The model predicts that both Δμ and BLA depend linearly on the weight ρ of form B (Fig. 3):

and

where BLAmax is the difference between the fully single and fully double bond lengths. Similarly, in the excited state, BLA* = − BLA = (2ρ−1)BLAmax. Combining (3) and (4), we obtain:

Two-form two-state model of optical transitions in red FP chromophore.

Only two electronic states, ground (S0) and excited (S1), are considered. The chromophore in the ground state is presented as a linear combination of the two limiting resonating forms, A and B, bottom. The A form (with wavefunction ΨΑ) represents the situation where the charge is fully localized on the acylamine oxygen and the B form (ΨB) – where it is localized on phenolic oxygen. The chromophore wavefunction in the ground state ΨG is: ΨG = (1−ρ)1/2 ΨA + (ρ)1/2 ΨB, where ρ is the relative weight of form B. The parameter ρ can be gradually tuned by applying different local electric field E to the chromophore (i.e. by varying local electrostatic environment in the series of proteins). The model further assumes that upon optical excitation the two limiting resonating forms transform to each other (ΨA → ΨB and ΨB → ΨA), implying that each of the forms undergoes a complete charge transfer. The excited state is then represented by (top): ΨE = (ρ)1/2 ΨA − (1−ρ)1/2 ΨB. If ΨA and ΨB are orthonormal,  (see30,31,32), one can easily show that

(see30,31,32), one can easily show that  depends linearly on ρ: Δμ = (1−2ρ)μmax, where

depends linearly on ρ: Δμ = (1−2ρ)μmax, where  .

.

For our particular problem of rotational dynamics around the exocyclic P- or I-bond of the red FP chromophore, it is reasonable to set the BLA parameter equal to a difference between the P- and I-bond lengths (BLA = lP − lI). Taking into account that the chromophore is not symmetric with respect to the bridge carbon atom, the permanent dipole difference Δμ will not be zero at the so-called “cyanine” limit where BLA = 0, but equal to some constant value Δμc. With these two refinements Eq. (5) will read:

Making use of the available crystallography data on several red FPs, including mStrawberry33, mCherry33, mPlum34 and DsRed35,36, we plot lP − lI versus Δμ in Fig. 4. This figure also includes two data points corresponding to the red FP chromophore in vacuum which we obtained using quantum mechanical calculations. The linear correlation between lP − lI and Δμ (R = −0.89, P = 0.008) provides an experimental support for the 2F2S model. Using (6) we estimate Δμc = (3.7 ± 1.2) D and μmax = (12.6 ± 2.9) D for the red FP chromophore.

Dependence of the difference between the P- and I-bond lengths on the change of permanent dipole moment (Δμ).

Circles represent experimental data points. The square symbol represents the quantum-mechanically calculated chromophore with the ground-state optimized (almost flat) geometry in vacuum. The star symbol represents the optimized geometry with the dihedral angle between phenol and imidazolinone rings constrained at 16°. The horizontal black dashed line corresponds to the “cyanine” limit where BLA = 0. The horizontal red dashed line shows the maximum possible BLA (lP − lI = 0.091 Å), corresponding to the neutral GFP chromophore37 where the P- and the I-bonds are basically single and double, respectively.

Correlation between photoconversion rate k1 and Δμ

Figure 5 shows the dependence of the photoconversion rate k1 on Δμ. With the increase of Δμ, the rate first exponentially decreases, then reaches the minimum at ~ 3 D and finally increases with about the same speed. Quite interestingly, the minimum point occurs near BLA* = 0, i.e. where the two bonds lengths are similar. Indeed, in mPlum, corresponding to point number 4, lP = 1.366 Å and lI = 1.358 Å, whereas the pure single and double bond lengths would be 1.451 ÷ 1.457 Å and 1.337 ÷1.366 Å, respectively, as in 2-benzylthio-3-i-butyl-5-(2-chlorophenylmethylidene)-4H-imidazoli-4-one)38 and in bare neutral GFP chromophore37. In the excited state, these bond lengths could probably slightly change, but, at least in the framework of 2F2S model, the BLA* in mPlum and probably mCherry at pH11 (point number 5) will be still very close to zero. The effective conjugation of the P- and I-bonds locks the chromophore in planar conformation and results in slowest photoconversion rates for these proteins. On the other hand, moving away from the minimum point leads to an elongation of one of the bonds, and, respectively, to an exponential increase of rotational rate. The sign of the BLA* (see top x-axis) implies that for the proteins with Δμ < 3 D the rotation around I-bond results in photoconversion, whereas for Δμ > 3.5 D, it is the rotation around P-bond.

Dependence of the rate of first photobleaching step on the change of permanent dipole moment.

The points numbering corresponds to, in increasing order, mTangerine, mStrawberry, mCherry, mPlum, mCherry at pH11, mTangerine/mCherry chimera, DsRed2, mStrawberry at pH 11, mBanana/mTangerine chimera, mStrawberry/DsRed2 chimera, mBanana, tdTomato/DsRed2 chimera and mCherry/tdTomato chimera. The top x-axis represents the BLA parameter in the excited state, i.e. same as in Fig. 4, but with opposite sign. The insets show the frequency of attempts (ν)9, maximum possible barrier height (a or b) and maximum possible change of permanent dipole moment (μmax), obtained from separate independent fits (red dashed lines) of the left and right branch of the dependence to Arrhenius law (see text). The continuous blue line shows the best fit of data to Eq. (13).

Assuming that the rotation about either bond occurs independently, we present the rate of the first photochemical step as a sum of the two contributions each described by Arrhenius law:

where ν is the frequency of attempts, E is the energy barrier for the rotation around the bond in the excited state, indexes P and I designate as before rotations around phenyl and imidazolinone exocyclic bonds, T is the temperature, R is the universal gas constant. Assuming that the barrier for rotation varies linearly with the weight of one of the forms shown in Fig. 3 (for justification see for example39), we can write: EP = aρ and EI = b(1−ρ), where a and b are the coefficients corresponding to the maximum possible barrier for the P- or I-bond, respectively, i.e. to the case when the corresponding bond is pure double. Substituting ρ from (3) into the above equations and taking into account that at BLA = 0, Δμ = Δμc, we obtain:

and

Substituting these expressions into (7) we get

where

On either side from the minimum point and not very close to it, only one term of (10) dominates, so we fitted each branch of experimental dependence shown in Fig. 5 with a segment of straight line and obtained the pairs of parameters C1, K1 and C2, K2 from the corresponding slopes and intercepts. The intersection of the two segments provides an independent estimation of Δμc = (3.0 ± 0.3) D, which matches within the experimental error the value found from structural data in the previous section. For a quantitative evaluation of limiting barrier heights a, b and corresponding μmax,1and μmax,2values, we used the frequencies of the P- and I-torsional vibrations in the excited state (νP = 4.7×1012 s−1and νI = 3.8×1012 s−1), calculated theoretically for the GFP model chromophore in vacuum9. Substituting these numbers, as well as C1, K1, C2 and K2 in the systems (11) and (12), we obtained a = (24.6 ± 3.8) kcal/mol, b = (24.3 ± 3.0) kcal/mol, μmax,1 = (10.4 ± 1.9) D, μmax,2 = (12.4 ± 2.2) D. Previous theoretical calculations of the excited-state potential energy of the neutral GFP chromophore (where the P-bond is purely double in the excited state) as a function of P-angle, obtained at either semiempirical7 or ab initio13 levels correlate to each other and predict the maximum barrier a = 30.5 kcal/mol7, agreeing well with our result.

A close coincidence of a and b suggests that the limiting barriers for rotations around P- and I- double bonds are very similar. Since also μmax,1 ≈ μmax,2 we can fit the whole experimental dataset with a symmetric function

containing only 3 fitting parameters: A = ν exp(−Emax/2RT) , K = Emax/2μmaxRT and Δμc, where ν is an effective frequency of vibrations, Emax is a maximum barrier height for rotation around the double bond. This approach better describes the region around Δμc, where two terms in (10) are similar. The result of the fitting is shown in Fig. 5. The following parameters were obtained: A = 2.51×103 s−1, K = 1.89 D−1, Δμc = 2.9 D. Defining ν = (νP + νI)/2 = 4.25×1012 s−1, we obtain Emax = (24 ± 1) kcal/mol and μmax = (11 ± 3) D, which are both in good agreement with the results of independent fitting of the right and left branches.

With these parameters in hand, we have estimated, using Eqs. (8) and (9), the barriers for rotations around P- and I-bonds for all the proteins in the excited state (see Supplementary Table). These values fall in the range between 9.8 kcal/mol and 14.4 kcal/mol.

Discussion

Olsen and Smith11 have recently calculated the structures and excited-state potential energy profiles for P- and I-rotations of the flat red FP chromophore in vacuum. They have shown that the rotation around the I-bond in the excited state encounters a potential barrier of 12.8 kcal/mol (using MRPT2 method) or 17 kcal/mol (using SA-CASSCF method). Using Δμ = 5.96 D for flat chromophore in vacuum (Fig. 4) and our experimental parameters, we estimate, according to (9), EI = 15.4 kcal/mol, which agrees well with theoretical predictions.

The good agreement of our experimental barriers (for both I- and P-rotations) with the high-level quantum-mechanical simulations strongly suggests that the first step of photobleaching consists in (either I- or P-bond) photoisomerization process and that the protein surrounding governs the twisting dynamics mainly by electronic effects. Alternatively, possible steric clashing of phenolate ring with the Ile161 residue upon rotation about the I-bond was discussed for DsRed40 and mCherry41. If the chromophore is pushed to the trans conformation without adjusting the rest of local structure, the two groups would come into the spatially forbidden contact. Our experimental results show that the chromophore in mTangerine, mStrawberry and mCherry undergoes a rotation around the I-bond in the excited state. All three proteins have Ile161, yet the photoconversion rate varies by an order of magnitude in the series, indicating that steric hindrance is not the main factor. (This is also consistent with the experimentally observed cis-trans isomerization in DsRed15). In fact, the potential energy for the rotation peaks near 90°11, where the van der Waals contact is not yet reached. In this case the barrier height would be still determined by electronic effects.

Interestingly, a similar conclusion about electronic effects has been drawn recently42 in a very different experimental approach where a large number of donor/acceptor substituted analogs of GFP chromophore were encapsulated in the so-called “octaacid” nanocavity, mimicking the β-barrel. It was shown that the substituent donating/withdrawing strength that tunes the resonance of the chromophore similarly to the effect of local field in proteins, strongly dominates the steric effects in controlling fluorescence efficiency. However, we note that for the red FPs considered here, rotations around either P- or I-bond in the excited state cannot compete with the radiative transition, because photoconversion rates are much less than 109 s−1 (Fig. 5). This would be possible only if the barriers for the I- or P-rotation were less than 4 ÷ 5 kcal/mol (cf. eq. (7)), which is indeed the case for a number of non-fluorescent GFP chromophore analogs in vacuum or non-protein environment (where either EI or EP < 5 kcal/mol7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,43,44 ).

Therefore we conclude that the protein-modulated electronic structure of the chromophore, namely the BLA in the bridge region, is the main factor in selecting the bond for rotation as well as the rotation speed. The isomerization in the excited state provides the trans-isomer in the case or I-rotation or ~90°-twisted conformer in the case of P-rotation. Whereas the first is quasi-stable in its ground state (seconds – minutes) even in vacuum11, the second is unstable in vacuum11, but is probably stabilized by protein matrix10 even more than the flat conformer due to the strong electrostatic and hydrogen bonding interactions of electronic density shifted to phenolate11 with nearby residues and water molecules34.

The fluorescent proteins are unique in biology: a monolithic β-barrel encapsulates and controls an otherwise wobbly chromophore. The linear and nonlinear absorption provides us with a window into how electrostatics within the protein can control conformational changes of the chromophore and while the opportunity to observe this effect is uniquely presented in fluorescent proteins, it is possible that the same mechanism may control the folding, structure and function of many different proteins.

Methods

Expression and purification of new RFP chimeras

Two portions of each of the Fruits and DsRed2 were amplified with PCR. The first portion contained the coding region from the start codon through to the 99th codon. The second portion extended from 94th codon to the termination. The overlapping 5 codons was used to join the various coding regions and clone the resulting chimera in pCP using a ligation-independent joining reaction (In Fusion, Clontech). pCP is a constitutive E. coli expression plasmid that appends a His tag to the N-terminus for purification. The proteins were purified using nickel affinity columns (Macherey-Nagel). The sequences and plasmids are freely available for research use at Addgene45.

Photophysical characterization of proteins

Absorption spectra, fluorescence spectra and excitation spectra of new FP mutants were measured and corrected as described before46. The fluorescence quantum yields were measured relatively to Rhodamine B in methanol46. Fluorescence lifetime was measured with a synchroscan streak camera (C5680-21, Hamamatsu) with 15-ps time resolution46.

Maximum extinction coefficient of all proteins was measured by using a gradual alkaline denaturation method, similarly to ref.47. The absorption spectral changes were monitored upon gradual titration of a protein solution with 1N NaOH. The extinction coefficient of the native FP form was obtained by selecting the linear part of the dependence of its peak optical density versus the optical density at 450 nm, corresponding to the anionic green FP chromophore in denatured form, for which εmax = 44,000 M−1 cm−148. If green immature form was also present, then its contribution to the denatured form as well as partial transformation of the red form to the green form was taken into account. The contributions of the red and green forms at 450 nm were also taken into account.

Evaluation of permanent dipole moments change

The 2PA spectra of DsRed2 and mFruits were published46 and those of new chimeras were obtained as described previously46. These spectra were then fitted with a sum of two one-photon excitation spectra29. The first corresponds to the independently measured excitation spectrum, whose amplitude was varied. The second corresponds to a blue-shifted experimental excitation profile whose shift and amplitude were varied. The amplitude of the first excitation profile was used as a two-photon absorption cross section value  (see Supplementary Fig. 1) in calculation of Δμ, according to the formula28,29:

(see Supplementary Fig. 1) in calculation of Δμ, according to the formula28,29:

where c is the speed of light, NAis the Avogadro's number, n is the refraction index of water, F = (n2+2)/3 is the Lorentz local field factor,  is the frequency (in cm−1) of the maximum one-photon absorption,

is the frequency (in cm−1) of the maximum one-photon absorption,  is the maximum extinction coefficient.

is the maximum extinction coefficient.

Measurements of photobleaching kinetics

Photobleaching kinetics were measured under continuous wave irradiation of the buffer solutions of purified proteins with Nd:YVO4 laser (Verdi, Coherent, 532 nm) and simultaneous detection of fluorescence signal at 90° with a A601f-2 CCD camera (Basler, Germany) through a 75-mm objective and a long-pass red filter transmitting λ > 690 nm. The whole volume of the solution (40 μl) contained in a fluorometer sub-micro cell (Starna Cells, Inc.. Atascadero, CA) was irradiated with a uniform photon flux which was attained by expanding the laser beam with a telescope to a cross-section larger than the cell input window. This geometry also ascertained the absence of diffusion contribution to the observed kinetics. The optical density of the samples at 532 nm was kept lower than 0.05 to provide constant excitation intensity along the 1-cm optical path of the laser. The operation of the camera and acquisition of fluorescence signal were computer-controlled with a LabView program. We have checked that a reference solution of Rhodamine 6G in dimethylformamide showed a single exponential photobleaching kinetics under these conditions (see Supplementary Fig. 2).

Quantum-chemical calculations

The structure of the “twisted” RFP chromophore (phenol ring being twisted and tilted out of coplanarity (~16°) with the imidazolinone ring) in vacuum was obtained by partial geometry optimization using Gaussian 0949 and the B3LYP/6-311++G(d,p) density functional and basis set. Angles and dihedrals involving the positioning of the phenol ring relative to the imidazolinone ring were frozen. The “flat” red FP chromophore model was generated by completely removing the angle and dihedral constraints placed on the phenol ring and its connection to the imidazolinone ring and performing geometry optimization as outlined above. The partially optimized “twisted” and “flat” structures were then analyzed using the INDO/S2-CIS method and the S0-->S1 Δµ values were obtained for these two models. The INDO/S2-CIS method used is a version that was provided by the original developer, Prof. Michael Zerner to Prof. Callis in 198050. In practice, calculations use INDO/1 one-electron integrals, Mataga-Nishimoto electron repulsion parameters and interaction scaling factors fσ = 1.267 and fπ = 0.585. The CI included 196 singly excited configurations generated from the 14 highest filled MOs and the lowest empty MOs, with no energy selection.

References

Chalfie, M. & Kain, S. R. (eds.) Green Fluorescent Protein, 2nd Ed.(Wiley, 2006).

Matz, M. V. et al. Fluorescent proteins from nonbioluminescent Anthozoa species. Nature Biotechnol. 17, 969–973 (1999).

Shaner, N. C. et al. Improved monomeric red, ornage and yellow fluorescent proteins derived from Discosoma sp. Red fluorescent protein. Nature Biotechnol. 22, 1567–1572 (2004).

Wang, L., Jackson, W. C., Steinbach, P. A. & Tsien, R. Y. Evolution of new nonantibody proteins via iterative somatic hypermutation. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101, 16745–16749 (2004).

Shaner, N. C. et al. Improving the photostability of bright monomeric orange and red fluorescent proteins. Nature Meth. 5, 545–551 (2008).

Subach, F. V. & Verkhusha, V. V. Chromophore transformations in red fluorescent proteins. Chem. Rev. 112, 4308–4327 (2012).

Voityuk, A. A., Michel-Beyerle, M.-E. & Rösch, N. Structure and rotation barriers for ground and excited states of the isolated chromophore of the green fluorescent protein. Chem. Phys. Lett. 296, 269–276 (1998).

Weber, W., Helms, V., McCammon, J. A. & Langhoff, P. W. Shedding light on the dark and weakly fluorescent states of green fluorescent proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96, 6177–6182 (1999).

Martin, M. E., Negri, F. & Olivucci, M. Origin, nature and fate of the fluorescent state of the green fluorescent protein chromophore at the CASPT2//CASSCF resolution. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126, 5452–5464 (2004).

Altoe, P., Bernardi, F., Garavelli, M., Orlandi, G. & Negri, F. Solvent effects on the vibrational activity and photodynamics of the green fluorescent protein chromophore: A quantum-chemical study. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127, 3952–3963 (2005).

Olsen, S. & Smith, S. C. Radiationless decay of red fluorescent protein chromophore models via twisted intramolecular charge-transfer states. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129, 2054–2065 (2007).

Olsen, S. & Smith, S. C. Bond selection in the photoisomerization reaction of anionic green fluorescent protein and kindling fluorescent protein chromophore models. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 8677–8689 (2008).

Olsen, S., Lamothe, K. & Martinez, T. J. Protonic gating of excited-state twisting and charge localization in GFP chromophores: A mechanistic hypothesis for reversible photoswitching. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 1192–1193 (2010).

Rafiq, S., Rajbongshi, B. K., Nair, N. N., Sen, P. & Ramanathan, G. Excited state relaxation dynamics of model green fluorescent protein chromophore analogs: Evidence for cis-trans isomerism. J. Phys. Chem. A 115, 13733–13742 (2011).

Habuchi, S. et al. Evidence for the isomerization and decarboxylation in the photoconversion of the red fluorescent protein DsRed. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127, 9877–8984 (2005).

Dean, K. et al. Analysis of red-fluorescent proteins provides insight into dark-state conversion and photodegradation. Biophys. J. 101, 961–969 (2011).

Heikal, A. A., Hess, S. T., Baird, G. S., Tsien, R. Y. & Webb, W. W. Molecular spectroscopy and dynamics of intrinsically fluorescent proteins: Coral red (dsRed) and yellow (Citrine). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97, 11996–12001 (2000).

Malvezzi-Campeggi, F., Jahnz, M., Heinze, K. G., Dittrich, P. & Schwille, P. Light-induced flickering of DsRed provides evidence for distinct and interconvertible fluorescent states. Biophys. J. 81, 1776–1785 (2001).

Schenk, A., Ivanchenko, S., Röcker, C., Wiedenmann, J. & Nienhaus, G. U. Photodynamics of red fluorescent proteins studied by fluorescence correlation spectroscopy. Biophys. J. 86, 384–394 (2004).

Hendrix, J., Floors, C., Dedecker, P., Hofkens, J. & Engelborghs, Y. Dark states in monomeric red fluorescent proteins studied by fluorescence correlation and single molecule spectrsocopies. Biophys. J. 94, 4103–4113 (2008).

Lounis, B., Deich, J., Rossel, F. I., Boxer, S. G. & Moerner, W. E. Photophysics of DsRed, a red fluorescent protein, from th e ensemble to the single-molecule level. J. Phys. Chem. B 105, 5048–5054 (2001).

Tolbert, L. M., Baldridge, A., Kowalik, J. & Solntsev, K. M. Collapse and recovery of green fluorescenct protein chromophore emission through topological effects. Acc. Chem. Res. 45, 171–181 (2012) and references therein.

Jung, G. et al. Fluorescence lifetime of fluorescent proteins. .In: Jung G. (ed.) Fluorescent Proteins I. Springer Series on Fluorescence 12, Ch. 11, pp. 69–97 (Springer, 2012).

Demachy, I. et al. Cyan fluorescent protein: Molecular dynamics, simulations and electronic absorption spectrum. J. Phys. Chem. B 109, 24121–24133 (2005).

Maddalo, S. L. & Zimmer, M. The role of the protein matrix in green fluorescent protein fluorescence. Photochem. Photobiol. 82, 367–372 (2006).

Jung, G., Wiehler, J. & Zumbusch, A. The photophysics of Green Fluorescent Protein: Influence of the key amino acids at positions 65, 203 and 222. Biophys. J. 88, 1932–1947 (2005).

Liano, T., Nifosi, R. & Tozzini, V. Relationship between structure and optical properties in green fluorescent proteins: A quantum mechanical study of the chromophore invironment. Chem. Phys. 298, 17–28 (2004).

Drobizhev, M., Tillo, S., Makarov, N. S., Hughes, T. E. & Rebane, A. Color Hues in red fluorescent proteins are due to internal quadratic Stark effect. J. Phys. Chem. B 113, 12860–12864 (2009).

Drobizhev, M., Makarov, N. S., Tillo, S., Hughes, T. E. & Rebane, A. Describing two-photon absorptivity of fluorescent proteins with a new vibronic coupling mechanism. J. Phys. Chem. B 116, 1736–1744 (2012).

Lu, D., Chen, G., Perry, J. W. & Goddard, W. A. III Valence-bond charge-transfer model for nonlinear optical properties of charge-transfer organic molecules. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 116, 10679–10685 (1994).

Barzoukas, M. Runser, C., Fort, A. & Blanchard-Desce, M. A two-state description of (hyper)polarizabilities of push-pull molecules based on a two-form model. Chem. Phys. Lett. 257, 531–537 (1996).

Painelli, A. & Terenziani, F. A non-perturbative approach to solvatochromic shifts of push-pull chromophores. Chem. Phys. Lett. 312, 211–220 (1999).

Shu, X., Shaner, N. C., Yarbrough, C. A., Tsien, R. Y. & Remington, S. J. Novel chromophores and buried charges control color in mFruits. Biochem. 45, 9639–9647 (2006).

Shu, X., Wang, L., Colip, L., Kallio, K. & Remington, S. J. Unique interactions between the chromophore and glutamate 16 lead to far-red emission in a red fluorescent protein. Prot. Sci. 18, 460–466 (2009).

Yarbrough, D., Wachter, R. M., Kallio, K., Matz, M. V. & Remintopn, S. J. Refined structure of DsRed, a red fluorescent protein from coral, at 2.0-Å resolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 462–467 (2001).

Wall, M. A., Socolich, M. & Ranganathan, R. The structural basis for red fluorescence in the tetrameric GFP homolog DsRed. Nature Struct. Biol. 7, 1133–1138 (2000).

Kurimoto, M. et al. Kinetic stabilization of biopolymers in single-crystal hosts: Green fluorescent protein in α-lactose monohydrate. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 121, 6952–6953 (1999).

Huang, X., Liu, Z., Yang, F. & Ding M. Synthesis and properties of novel imidazolone derivatives containing a sulfur atom. Phosphorus, Sulfur and Silicon 182, 939–950 (2007).

Kemnitz, C. R. & Loewen, M. J. “Amide resonance” correlates with a breadth of C-N rotation barriers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129, 2521–2528 (2007).

Chudakov, D. M., Feofanov, A. V., Mudrik, N. N., Lukyanov, S. & Lukyanov, K. A. Chromophore environment provides clue to “kindling fluorescent protein” riddle. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 7215–7219 (2003).

Stiel, A. C. et al. Generation of monomeric reversibly switchable red fluorescent proteins for far-field fluorescence nanoscopy. Biophys. J., 95, 2989–2997 (2008).

Baldridge, A., Samanta, S. R., Jayaraj, N., Ramamurthy, V. & Tolbert, L. M. Steric and electronic effects in capsule-confined green fluorescent protein chromophores. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 712–715 (2011).

Follenius-Wund, A. et al. Fluorescent derivatives of the GFP chromophore give a new insight into the GFP fluorescence process. Biophys. J. 85, 1839–1850 (2003).

Litvinenko, K. L., Webber, N. M. & Meech, S. R. Internal conversion in the chromophore of the green fluorescent protein: Temperature dependence and isoviscosity analysis. J. Phys. Chem. A 107, 2616–2623 (2003).

http://www.addgene.org/ (19 July 2012).

Drobizhev, M., Makarov, N. S., Tillo, S., Hughes, T. E. & Rebane, A. Two-photon absorption properties of fluorescent proteins. Nature Meth. 8, 393–399 (2011).

Kredel, S. et al. Optimized and far-red-emitting variants of fluorescent protein eqFP611. Chem. Biol. 15, 224–233 (2008).

Ward, W. W. Biochemical and physical properties of green fluorescent protein. In: Chalfie, M. & Kain, S. R. (eds.) Green Fluorescent Protein 2nd Ed. (Wiley, 2006) Ch. 3., pp. 39–65.

http://www.gaussian.com/g_tech/g_ur/m_citation.htm (19 July 2012).

Ridley, J. & Zerner, M. Intermediate Neglect of Differential Overlap (INDO) Technique for Spectroscopy: Pyrrole and the Azines. .Theor. Chim. Acta (Berlin) 32, 111–134 (1973).

Acknowledgements

We thank Seth Olsen for useful discussion and Bret Davis and Jeff Simkins for technical help. This work was supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences grant R01 GM086198.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MD and TEH wrote the main manuscript text, YS, PW and AR designed and assembled the experimental setup, JNS and PRC accomplished quantum mechanical calculations, AM and MD acquired and analyzed experimental data and TEH, KO'D and LD designed, expressed and purified fluorescent proteins. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Drobizhev, M., Hughes, T., Stepanenko, Y. et al. Primary Role of the Chromophore Bond Length Alternation in Reversible Photoconversion of Red Fluorescence Proteins. Sci Rep 2, 688 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep00688

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep00688

This article is cited by

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.