Abstract

The present knowledge of microbial community mainly focus on total sponge, the spatial distribution of microbes in sponges is rarely known, especially those with potential ecological functions. In this study, based on gene library and ∫-LIBSHUFF analysis, the spatial distribution of prokaryotic symbionts and nitrogen cycling genes in the cortex and endosome sections of sponge Astrosclera willeyana were investigated. A significance difference of bacterial phylotypes between the cortex and endosome was revealed. For example Bacteroidetes, Frankineae and Propionibacterineae were detected only in the endosome, whereas Cyanobacteria, Planctomycetacia and Micrococcineae were only associated with the cortex. Some branches of α-Proteobacteria, γ-Proteobacteria, Corynebacterineae, Acidimicobidae, Crenarchaeota and Euryarchaeota also showed distribution difference. Bacterial denitrifiers and ammonia oxidizing bacteria (AOB) were observed using nirS and amoA genes as markers. Particularly, AOB were only associated with the endosome. This study highlighted the spatial distribution of bacterial symbionts especially those with ammonia oxidization function.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Marine sponges are hosts of diverse marine microorganisms1,2,3. The association between microorganisms and their host has been studied firstly using microscopic observation and culture-dependent approach4,5. Nucleic acid-based culture-independent molecular techniques have demonstrated the extraordinary microbial diversity associated with sponges2,3,6,7 and sponge-specific microbes which are different from those in the environmental seawater have been suggested2,3. In recent years deep sequencing has demonstrated the presence of as many as 27 bacterial phyla and 8 candidate divisions in sponges8,9,10. However there is only limited information on the spatial distributions of these populations as most studies have focused on the microbial population of the complete sponge.

As sessile filter-feeding organisms, sponges pump large amounts of water through their channel system. As a consequence of seawater pumping in and out the sponge body, an oxygen concentration gradient in sponge body may occur11,12. Thus, it can be hypothesized that a spatial distribution of microorganisms in sponges probably exists because of the filtering by canals with different apertures and the different inner-environments e.g. oxygen. It is reasonable that the microbial population on the sponge surface is different form that in the sponge mesohyl13. But, the microbial spatial distribution in the sponge body remains largely unknown. The exploratory survey of spatial distribution of microorganisms in sponge body was first made in 2000 to investigate the spatial arrangement of Desulfovibrionaceae14. Since 2007, the microbial spatial distribution in sponges has drawn people's more attention15,16,17. However different results have been observed, for example, the spatial distribution of microorganisms within the body of sponges Polymastia cf. corticata and Tethya aurantium was found to be specific15,16, while a homogeneous spatial distribution of microorganisms in sponge T. californiana was indicated17. Meanwhile, to date, we have no information on the distribution of Euryarchaeota in sponges. In addition, though many reports have suggested the nitrogen cycling mediated by the sponge-associated microbes since 200618,19,20,21, only the spatial distribution of ammonia monooxygenase amoA gene in sponge Polymastia cf. corticata has been investigated16. Thus, more investigations need to be carried out on the spatial distribution of microbial symbionts especially those with ecological functions in different sponges to provide more evidence for the spatial distribution hypothesis and increase the understanding of related microbial functions.

The sponge Astrosclera willeyana provides an ideal species for microbial spatial distribution investigation because it is characterized by a round sphere shape. In this study, using gene library-based molecular approach and statistical ∫-LIBSHUFF analysis, the spatial distribution of prokaryotic symbionts, especially those with nitrogen-cycling function, in the cortex and endosome of sponge A. willeyana were investigated. The spatial distribution difference of microbial symbionts in the cortex and endosome of A. willeyana, particularly ammonia oxidizing bacteria (AOB) in the endosome is suggested. This is the first time that the spatial distribution of bacterial denitrifiers with nirS gene and Euryarchaeota in sponges has been demonstrated.

Results

Four 16S rRNA gene libraries of bacteria, actinobacteria, cyanobacteria and archaea and two functional gene libraries of nirS and amoA genes were constructed. Diverse bacterial phylotypes including actinobacteria and cyanobacteria and archaeal phylotypes were detected in sponge A. willeyana. The ammonia monooxygenase amoA gene and the nitrite reductase nirS gene were also observed. In contrast, the bacterial anaerobic ammonia oxidation of bacteria, archaeal ammonium oxidation, nitrite reductase nirK, nitric oxide reductase norB, cytochrome nitrite reductase nrf, nitrite oxidoreductase nxr and nitrogen fixation nif genes were not detected (Table 1). A total of 334 clones from these six gene libraries were sequenced successfully and the number of sequenced sequences was saturated based on rarefaction analysis (Fig. S1). According to Table 1, bacteria including those with nirS gene, archaea and actinobacteria were detected in both endosome and cortex samples. Notably, cyanobacteria were only observed in the cortex and the amoA gene was only found in the endosome suggesting some extent of spatial distribution. At the level of OTU, these results also indicated different microbial populations between the cortex and endosome of sponge A. willeyana.

The spatial distribution of bacteria

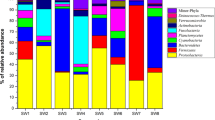

Based on the 16S rRNA gene library using universal primer for bacteria (Fig. 1-1), diverse bacterial phylotypes including Planctomycetes, Cyanobacteria, Bacteroidetes, Firmicutes, α-Proteobacteria, γ-Proteobacteria and Actinobacteria were observed in the endosome and cortex of sponge A. willeyana. γ-Proteobacteria dominated in both endosome and cortex samples (51.72% and 30%, respectively) followed by α-Proteobacteria. Firmicutes were also found in endosome and cortex. Particularly, Bacteroidetes (8.62%) was only associated with the endosome (Fig. 1-1A), while Planctomycetes (28.33%) and Cyanobacteria (10%) were only observed in the cortex (Fig. 1-1B). As shown in Fig 2, 2 of 5 OTUs of γ-Proteobacteria were detected only in the cortex, the other 2 OTUs were detected only in the endosome, while the remaining one was overlapped. In the case of α-Proteobacteria, 3 of 5 OTUs were detected only in the cortex, 1of 5 was present only in the endosome and the remaining one was overlapped in two sections.

NJ-phylogenetic tree based on bacteria 16S rRNA gene sequences (1,420–1,520bp) without actinobacteria.

Bootstrap values (1,000 replicates) lower than 50% are not shown.  mark means the OTU only in the cortex and

mark means the OTU only in the cortex and  mark means the OTU only in the endosome.

mark means the OTU only in the endosome.  mark means the OTU in both cortex and endosome samples. The number inside the parenthesis means the number of sequences within each OTU.

mark means the OTU in both cortex and endosome samples. The number inside the parenthesis means the number of sequences within each OTU.

In Fig. 1-1A, actinobacteria were found in the endosome rather than in the cortex. However, using actinobacteria specific primer, a total of 118 actinobacteria 16S rRNA gene sequences were observed in the cortex and endosome sections. Acidimicrobidae and Actinobacteridae including Propionibacterineae, Frankineae, Micrococcineae and Corynebacterineae were found (Fig. 1–2). Acidimicrobidae dominated the actinobacterial community in the endosome and cortex (73.85% and 77.14%) followed by Corynebacterineae. Particularly, Propionibacterinea (6.15%) and Frankineae (3.08%) were only found in the endosome, while Micrococcineae (8.57%) was only found in the cortex. Fig. 3 shows that 6 of 10 OTUs of Acidimicrobidae were detected only in the endosome and 2 only in the cortex. The remaining 2 OTUs were overlapped. One OTU of Propionibacterineae, one OTU of Frankineae and 2 of 3 OTUs of Corynebacterineae were only present in the endosome, while 2 OTUs of Micrococcineae were only observed in the cortex. Therefore, actinobacteria also exhibited obvious spatial distribution difference.

NJ-phylogenetic tree based on actinobacteria 16S rRNA gene sequences (639 bp).

Bootstrap values (1,000 replicates) lower than 50% are not shown.  mark means the OTU only in the cortex and

mark means the OTU only in the cortex and  mark means the OTU only in the endosome.

mark means the OTU only in the endosome.  mark means the OTU in both cortex and endosome samples. The number inside the parenthesis means the number of sequences within each OTU.

mark means the OTU in both cortex and endosome samples. The number inside the parenthesis means the number of sequences within each OTU.

The spatial distribution of archaea

A total of 36 archaea 16S rRNA gene sequences were obtained. As shown in Fig. 1–3, Crenarchaeota and Euryarchaeota were detected in both endosome and cortex sections with Crenarchaeota as the predominant group, i.e. 88.89% and 61.11% in the endosome and cortex, respectively. As shown in Fig. 4, Crenarchaeota and Euryarchaeota were observed in both sections, but some OTUs were found only in the cortex.

NJ-phylogenetic tree based on archaea 16S rRNA gene sequences (913bp).

Bootstrap values (1,000 replicates) lower than 50% are not shown.  mark means the OTU only in the cortex and

mark means the OTU only in the cortex and  mark means the OTU in both cortex and endosome samples. The number inside the parenthesis means the number of sequences within each OTU.

mark means the OTU in both cortex and endosome samples. The number inside the parenthesis means the number of sequences within each OTU.

The spatial distribution of ammonia-oxidizing bacteria and bacterial denitrifiers

As for microbial functional genes, 1 of 2 OTUs of bacterial nirS gene was found only in the cortex, while another was overlapped between two samples (Fig. 5). Both OTUs of bacterial amoA genes were only found in the endosome indicating their space-specific distribution in this sponge (Fig. 6).

The comparison of prokaryotic populations and nitrogen cycling genes between the cortex and endosome of sponge Astrosclera willeyana

Fig. 7 summarizes the spatial distribution of sponge prokaryotic symbionts and their nir and amoA genes (represented by OTUs). Obviously, different spatial distribution of bacteria and those with nirS and amoA genes in the cortex and endosome was indicated. For example, Bacteroidetes, Frankineae, Propionibacterineae and AOB (with dotted line box in Fig. 7) are space-specific in the endosome, while Cyanobacteria, Planctomycetacia and Micrococcineae (with solid line box in Fig. 7) are cortex-specific. In addition, some α-Proteobacteria, γ-Proteobacteria, Corynebacterineae and Acidimicobidae show spatial distribution difference. In the case of functional genes involved in the ammonia-oxidization and denitrification, the amoA gene is only associated with the endosome section.

Spatial distribution of the prokaryotic symbionts and functional genes in the South China Sea sponge A. willeyana.

The outer orange circle of the lower half represents the cortex sample. The inner yellow circle represents the endosome sample. The upper half of the figure means the shared microbes or genes in two samples. The phylum which was detected only in the cortex sample or only in the endosome sample was surrounded by solid line box or dotted line box. Number refers to the number of OTUs.

The result of statistical analysis of bacterial community, archaeal community and nirS gene spatial distribution difference between the cortex and endosome by ∫-LIBSHUFF is exhibited in Table S1 (the gene libraries of cyanobacteria and actinobacteria were included in the bacterial library). Because amoA gene shows certain spatial specificity, the amoA gene sequences were not analyzed by ∫-LIBSHUFF. According to Table S1, a significance difference of bacterial phylotypes between the cortex and endosome is suggested because of the P-value below 0.098 at the 0.05 level. Though some archaeal OTUs are associated only with cortex (Fig. 4), no statistically significant difference of spatial distribution of archaea was suggested according to ∫-LIBSHUFF analysis. Meanwhile, bacterial nirS genes in endosome and cortex also did not exhibit a significant difference.

Discussion

In common with most sponges, A. willeyana contains a large population of Proteobacteria, especially γ-Proteobacteria, as the dominant group of its bacterial community3,6,7,10. However there is only spatial differentiation within a few of its branches. Similarly, Acidimicrobidae, which has been grouped into sponge-specific microorganisms3, shows no spatial specificity. In contrast, Bacteroidetes, Cyanobacteria and Planctomycetacia show obvious spatial distribution specificity. Cyanobacteria has been observed widely in sponges22, its space-specific distribution in the cortex of sponge A. willeyana maybe related to its biological functions e.g. photosynthesis23. Interestingly, Cyanobacteria was detected only in the endosome of sponge Tethya aurantium Pallas 176615, which indicated that microbial spatial distribution maybe sponge species-dependent.

Diverse sponge-associated actinobacteria have been revealed24,25,26. In this study actinobacteria did show a strong selectivity in the spatial location, for example Frankineae, Propionibacterineae in the endosome and Micrococcineae in the cortex. Meanwhile, the abundance of actinobacteria in the endosome is greater than that in the cortex. It is worth mentioning that, in this study, a significant difference of DNA specificity between bacterial 16S rRNA gene universal primer and actinobacteria 16S rRNA gene specific primer was observed. Actinobacterial 16S rRNA gene specific primer is much more sensitive to sponge-associated actinobacteria DNA than bacterial 16S rRNA gene universal primer. For instance, using bacteria 16S rRNA gene universal primer only one actinobacteria OTU was detected. In contrast, Acidimicrobidae, Corynebacterineae, Propionibacterineae and Micrococcineae were detected using actinobacterial specific primer. This result suggests that the species-specific primers are very important for the diversity study of sponge microbial symbionts.

Group I Crenarchaeota are widely distributed in the marine environment27. Almost all sponge-associated archaea belong to this group28,29,30,31, while Euryarchaeota appeared in few sponges8. In this study, both Crenarchaeota and Euryarchaeota were detected in sponge A. willeyana. It was the first time to reveal the homogeneous spatial distribution of Euryarchaeota in sponges. Though some archaeal OTUs were only observed in the cortex, archaea show no significant distribution difference between the cortex and endosome of sponge A. willeyana.

In the process of nitrification, ammonia monooxygenase (amo) is an important enzyme for oxidizing ammonia to hydroxylamine. The process of turning nitrite to nitrogen oxide catalyzed by nitrite reductase is an important limiting step of denitrification. Nitrite reductase can be classified into two types, copper-type nitrite reductase (the product of the nirK) and cytochrome-type (the product of the nirS)32. In the absence of appropriate 16S rRNA gene to look for specific ammonia-oxidizing bacteria and denitrifying bacteria, genes encoding ammonia monooxygenase (amoA) and nitrite reductase (nirK and nirS) are often used as molecular markers to study homologous microbial diversity33,34,35. In this study, bacterial nirS and amoA genes were found in the South China Sea sponge A. willeyana, suggesting the presence of bacterial denitrifiers and ammonia-oxidizing bacteria in this sponge.

It should be mentioned that, the amoA gene of β-Proteobacteria showed no spatial distribution difference in sponge Polymastia cf. corticata16. However in this study, the bacterial amoA genes were found only in the endosome of sponge A. willeyana exhibiting spatial distribution specificity. This maybe a result of different Proteobacteria groups in these different two sponges, e.g. α-Proteobacteria and γ-Proteobacteria rather than β-proteobacteria were observed in sponge A. willeyana. It is suggested that ammonia-oxidizing archaea (AOA) dominate the process in low ammonia nitrogen level area, while in an area of high level ammonia nitrogen, AOB may take on the dominator role instead of archaea36. In this study AOB was found in sponge A. willeyana, which is in consist with the results of sponge Polymastia cf. corticata16, indicating the important nitrification role of AOB in sponges because of high level of ammonia nitrogen released by the host as a metabolic waste.

Denitrification is generally considered as a process medicated by bacteria under low oxygen concentration37,38,39. During sponge's filter-feeding, the internal oxygen concentration changes because of the water pumping11,40. If the oxygen concentration reduces to a low level when water pumping out, it just creates a condition for denitrification process. In this study, nirS gene was detected in cortex and endosome sections. It was the first time to investigate the spatial distribution of bacterial denitrifiers with nirS gene in sponges.

Sponge microbial symbionts are proposed to be captured by a combination of horizontal and vertical transmission2. As filter feeders, sponges are suggested to select microorganisms in the different areas of their bodies41. The microbial spatial distribution hypothesis is helpful to explain the different microbial community in different spatial locations within one sponge and then understand the related microbial functions. The revealed complex but unique microbial communities in the cortex and endosome of sponge A. willeyana in this study provide new evidence for the spatial distribution hypothesis on sponge microbial symbionts. It is suggested that more sponge species with different shape and different microbial community should be investigated to provide more information for the microbial spatial distribution in sponges. Meanwhile, further research should be undertaken to confirm that whether there is a particular selective mechanism in sponges resulting in the spatial distribution of microbial community.

Methods

Sponge sampling

Sponge was collected from the Yongxing island (112°20′E, 16°50′N) in the South China Sea by diving at a depth of ca. 20 m. It was placed in an ice-cooled box and transported to the laboratory immediately. The sponge sample was identified as Astrosclera willeyana according to 28S rRNA gene with 99% identify.

DNA extraction and PCR amplification

Sponge was rinsed 3 times by artificial seawater (ASW) (1.1 g CaCl2, 10.2 g MgCl2·6H2O, 31.6 g NaCl, 0.75 g KCl, 1.0 g Na2SO4, 2.4 g Tris-HCl, 0.02 g NaHCO3, 1 L distilled water, pH 7.6). A-endosome sample and B-cortex sample were obtained from the cortex and endosome sections of sponge A. willeyana, respectively (six parallel samples from each section, Fig. S2). The spatial samples were washed 3 times with ASW and separately grinded using sterilized mortars and pestles. Then the genomic DNA was extracted and purified using the QIAGEN DNeasy Tissue Kit following the manufacturer's protocol. The mixed DNA from three parallel samples for each section was used for PCR.

The primers and PCR conditions used to amplify 16 S rRNA gene and functional gene fragments are shown in Table S233,34,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52. The PCR mixture (50 µL) contained 200 ng template DNA, 250 µM dNTPs, 0.2 µM of each primer, 2.5 U of TransStart Fastpfu DNA polymerase (TransGen) and 1×TransStart FastPfu Buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.8, 10 mM KCl, 10 mM (NH4)2SO4, 2 mM MgSO4).

Gene library construction, phylogenetic and ∫-LIBSHUFF analysis

The amplified products were recovered and purified using Agarose Gel DNA Purification Kit (Takara, Dalian). Purified PCR products were cloned with the pEASY-Blunt Cloning kit (TransGen) following the manufacturer's instructions. The positive recombinants were screened on X-Gal (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indoly-β-D-galactopyranoside)-IPTG (isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactopyranoside) -ampicillin plates by color-based recombinant selection. The positive clones were further identified by vector primers M13F/R. Sequencing of plasmids was performed using vector primers on ABI 3730xl capillary sequencers (Applied Biosystems).

Using DOTUR software, sequences of all 16S rRNA genes with similarities > 97% were considered as one operational taxonomic unit (OTU), while functional gene sequences with similarities > 92% were considered as one OTU53. The diversity was determined by rarefaction analysis using OriginPro (Version 8). DNA sequences were aligned with Clustal W and classified using the RDP (http://rdp.cme.msu.edu/index.jsp) classifier with a confidence threshold of 70%. All OTUs' representative sequences, their nearest neighbors and some reference sequences were imported in MEGA (Version 5). Neighbor-Joining phylogenetic tree was constructed using software package PHYLIP54. The difference analysis between the two libraries of cortex and endosome samples was carried out with ∫-LIBSHUFF55.

Nucleotide sequence accession number

All representative sequences were deposited in Genbank under accession numbers: JQ362353 (sponge Astrosclera willeyana 28S rRNA gene), JN113042-JN113058 (actinobacteria 16S rRNA gene), JN113059-JN113064 (archaea 16S rRNA gene), JN113065-JN113084 (bacteria 16S rRNA gene), JN113085-JN113086 (cyanobacteria 16S rRNA gene), JN113087-JN113088 (nirS gene) and JN113089-JN113090 (amoA gene).

References

Friedrich, A. B., Fischer, I., Proksch, P., Hacker, J. & Hentschel, U. Temporal variation of the microbial community associated with the mediterranean sponge Aplysina aerophoba. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 38, 105–113 (2001).

Hentschel, U., Hopke, J., Horn, M., Friedrich, A. B., Wagner, M. et al. Molecular evidence for a uniform microbial community in sponges from different oceans. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68, 4431–4440 (2002).

Taylor, M. W., Radax, R., Steger, D. & Wagner, M. Sponge-associated microorganisms: Evolution, ecology and biotechnological potential. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rew. 71, 295–324 (2007).

Vacelet, J. & Donadey, C. Electron microscope study of the association between some sponges and bacteria. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 30, 301–314 (1977).

Webster, N. S. & Hill, R. T. The culturable microbial community of the Great Barrier Reef sponge Rhopaloeides odorabile is dominated by an α-Proteobacterium. Mar. Biol. 138, 843–851 (2001).

Hentschel, U., Usher, K. M. & Taylor, M. W. Marine sponges as microbial fermenters. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 55, 167–177 (2006).

Hardoim, C. C., Costa, R., Araújo, F. V., Hajdu, E., Peixoto, R. et al. Diversity of bacteria in the marine sponge Aplysina fulva in Brazilian coastal waters. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75, 3331–3343 (2009).

Webster, N. S., Taylor, M. W., Behnam, F., Lücker, S., Rattei, T. et al. Deep sequencing reveals exceptional diversity and modes of transmission for bacterial sponge symbionts. Environ. Microbiol. 12, 2070–2082 (2010).

Lee, O. O., Wang, Y., Yang, J. K., Lafi, F., Al-Suwailem, A. & Qian, P. Pyrosequencing reveals highly diverse and species-specific microbial communities in sponges from the Red Sea. ISME J. 5, 650–664 (2011).

Schmitt, S., Tsai, P., Bell, J., Fromont, J., Ilan, M. et al. Assessing the complex sponge microbiota: core, variable and species-specific bacterial communities in marine sponges. ISME J. 6, 564–576 (2012).

Schönberg, C. H. L., Hoffmann, F. & Gatti, S. Using microsensors to measure sponge physiology. Boll. Mus. Ist. Biol. Univ. Genova 68, 593–60 (2004).

Schläppy, M., Weber, M., Mendola, D., Hoffmann, F. & de Beer, D. Heterogeneous oxygenation resulting from active and passive flow in two Mediterranean sponges, Dysidea avara and Chondrosia reniformis. Limnol. Oceanogr. 55, 1289–1300 (2010).

Gerce, B., Schwartz, T., Syldatk, C. & Hausmann, R. Difference between bacterial communities associated with the surface or tissue of Mediterranean sponge species. Microb. Ecol. 61, 769–782 (2011).

Manz, W., Arp, G. & Schumann-Kindel, G. Widefield deconvolution epifluorescence microscopy combined with fluorescence in situ hybridization reveals the spatial arrangement of bacteria in sponge tissue. J. Microbiol. Meth. 40, 125–134 (2000).

Thiel, V., Neulinger, S. C., Staufenberger, T., Schmaljohann, R. & Imhoff, J. F. Spatial distribution of sponge-associated bacteria in the Mediterranean sponge Tethya aurantium. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 59, 47–63 (2007).

Meyer, B. & Kuever, J. Phylogenetic diversity and spatial distribution of the microbial community associated with the Caribbean deep-water sponge Polymastia cf. corticata by 16S rRNA, aprA and amoA gene analysis. Microb. Ecol. 56, 306–321 (2008).

Sipkema, D. & Blanch, H. W. Spatial distribution of bacteria associated with the marine sponge Tethya californiana. Mar. Biol. 157, 627–638 (2010).

Hallam, S. J., Mincer, T. J., Schleper, C., Preston, C. M., Roberts, K. et al. Pathways of carbon assimilation and ammonia oxidation suggested by environmental genomic analyses of marine Crenarchaeota. PLoS Biol. 4, 520–536 (2006).

Steger, D., Ettinger-Epstein, P., Whalan, S., Hentschel, U., de Nys, R. et al. Diversity and mode of transmission of ammonia-oxidizing archaea in marine sponges. Environ. Microbiol. 10, 1087–1094 (2008).

Bayer, K., Schmitt, S. & Hentschel, U. Physiology, phylogeny and in situ evidence for bacterial and archaeal nitrifiers in the marine sponge Aplysina aerophoba. Environ. Microbiol. 10, 2942–2955 (2008).

Mohamed, N. M., Saito, K., Tal, Y. & Hill, R. T. Diversity of aerobic and anaerobic ammonia-oxidizing bacteria in marine sponges. ISME J. 4, 38–48 (2010).

Webb, V. L. & Maas, E. W. Sequence analysis of 16S rRNA gene of cyanobacteria associated with the marine sponge Mycale (Carmia) hentscheli. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 207, 43–47 (2002).

Zehr, J. P. & McReynolds, L. A. Use of degenerate oligoncleotides for amplification of the nifH gene from the marine cyanobacterium Trichodesmium-thiebautii. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 55, 2522–2526 (1989).

Li, Z. Y. & Liu, Y. Marine sponge Craniella austrialiensis-associated bacterial diversity revelation based on 16S rDNA library and biologically active actinomycetes screening, phylogenetic analysis. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 43, 410–416 (2006).

Zhang, H., Lee, Y. K., Zhang, W. & Lee, H. K. Culturable actinobacteria from the marine sponge Hymeniacidon perleve: isolation and phylogenetic diversity by 16S rRNA gene-RFLP analysis. Anton. Leeuw. Int. J G 90, 159–169 (2006).

Jiang, S., Sun, W., Chen, M., Dai, S., Zhang, L. et al. Diversity of culturable actinobacteria isolated from marine sponge Haliclona sp. Anton. Leeuw. Int. J G 92, 405–416 (2007).

Karner, M. B., DeLong, E. F. & Karl, D. M. Archaeal dominance in the mesopelagic zone of the Pacific Ocean. Nature 409, 507–510 (2001).

Preston, C. M., Wu, K. Y., Molinski, T. F. & DeLong, E. F. A psychrophilic crenarchaeon inhabits a marine sponge: Cenarchaeum symbiosum gen nov, sp, nov. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93, 6241–6246 (1996).

Margot, H., Acebal, C. & Toril, E. Consistent association of crenarchaeal archaea with sponges of the genus Axinella. Mar. Biol. 140, 739–745 (2002).

Lee, E. Y., Lee, H. K., Lee, Y. K., Sim, C. J. & Lee, J. H. Diversity of symbiotic archaeal communities in marine sponges from Korea. Biomol. Eng. 20, 299–304 (2003).

Holmes, B. & Blanch, H. Genus-specific associations of marine sponges with group I crenarchaeotes. Mar. Biol. 150, 759–772 (2007).

Heylen, K., Gevers, D., Vanparys, B., Wittebolle, L., Geets, J., Boon, N. & De Vos, P. The incidence of nirS and nirK and their genetic heterogeneity in cultivated denitrifiers. Environ. Microbiol. 8, 2012–2021 (2006).

Rotthauwe, J. H., Witzel, K. P. & Liesack, W. The ammonia monooxygenase structural gene amoA as a functional marker: Molecular fine-scale analysis of natural ammonia-oxidizing populations. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63, 4704–4712 (1997).

Braker, G., Fesefeldt, A. & Witzel, K. P. Development of PCR primer systems for amplification of nitrite reductase genes (nirK and nirS) to detect denitrifying bacteria in environmental samples. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64, 3769–3775 (1998).

Braker, G., Zhou, J. Z. & Wu, L. Y. Nitrite reductase genes (nirK and nirS) as functional markers to investigate diversity of denitrifying bacteria in Pacific Northwest marine sediment sommunities. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66, 2096–2104 (2000).

Di, H. J., Cameron, K. C., Shen, J. P., Winefield, C. S., O'Callaghan, M. et al. Nitrification driven by bacteria and not archaea in nitrogen-rich grassland soils. Nat. Geosci. 2, 621–624 (2009).

Zumft, W. G. Cell biology and molecular basis of denitrification. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rew. 61, 533–545 (1997).

Hoffmann, F., Radax, R., Woebken, D., Holtappels, M., Lavik, G. et al. Complex nitrogen cycling in the sponge Geodia barretti. Environ. Microbiol. 11, 2228–2243 (2009).

Fiore, C. L., Jarett, J. K., Olson, N. D. & Lesser, M. P. Nitrogen fixation and nitrogen transformations in marine symbioses. Trends Microbiol. 18, 455–463 (2010).

Sarà, M. A study on the genus Tethya (Porifera, Demospongiae) and new perspectives in sponge systematics. in: Vacelet J., Boury-Esnault, N. (eds.). Taxonomy of Porifera from the N.E. Atlantic and Mediterranean Sea. NATO ASI Ser, Ser G: Ecol Sci 13. Springer: Berlin. pp. 205–225 (1987).

Wehrl, M., Steinert, M. & Hentschel, U. Bacterial uptake by the marine sponge Aplysina aerophoba. Microb. Ecol. 53, 355–365 (2007).

Lane, D. J., Pace, B., Olsen, G. J., Stahl, D. A., Sogin, M. L. et al. Rapid determination of 16S ribosomal-RNA sequences for phylogenetic analyses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 82, 6955–6959 (1985).

Delong, E. F. Archaea in coastal marine environment. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89, 5685–5689 (1992).

Martin-Laurent, F., Philippot, L., Hallet, S., Chaussod, R., Germon, J. C. et al. DNA extraction from soils: Old bias for new microbial diversity analysis methods. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67, 2354–2359 (2001).

Philippot, L., Piutti, S., Martin-Laurent, F., Hallet, S. & Germon, J. C. Molecular analysis of the nitrate-reducing community from unplanted and maize-planted soils. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68, 6121–6128 (2002).

Mohan, S. B., Schmid, M., Jetten, M. & Cole, J. Detection and widespread distribution of the nrfA gene encoding nitrite reduction to ammonia, a short circuit in the biological nitrogen cycle that competes with denitrification. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 49, 433–443 (2004).

Stach, J. E., Maldonado, L. A., Ward, A. C., Goodfellow, M. & Bull, A. T. New primers for the class actinobacteria: application to marine and terrestrial environments. Environ. Microbiol. 5, 828–841 (2003).

Casciotti, K. L. & Ward, B. B. Phylogenetic analysis of nitric oxide reductase gene homologues from aerobic ammonia-oxidizing bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 52, 197–205 (2005).

Francis, C. A., Roberts, K. J., Beman, J. M., Santoro, A. E. & Oakley, B. B. Ubiquity and diversity of ammonia-oxidizing archaea in water columns and sediments of the ocean. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102, 14683–14688 (2005).

Vanparys, B., Bodelier, P. & De Vos, P. Validation of the correct start codon of norX/nxrX and universality of the norAXB/nxrAXB gene cluster in Nitrobacter species. Curr. Microbiol. 53, 255–257 (2006).

Clementino, M. M., Vieira, R. P., Cardoso, A. M., Nascimento, A. P. & Silveira, C. B. Prokaryotic diversity in one of the largest hypersaline coastal lagoons in the world. Extremophiles 12, 595–604 (2008).

Jetten, M. S., Niftrik, L., Strous, M., Kartal, B., Keltjens, J. T. et al. Biochemistry and molecular biology of anammox bacteria. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 44, 65–84 (2009).

Schloss, P. D. & Handelsman, J. Introducing DOTUR, a computer program for defining operational taxonomic units and estimating species richness. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71, 1501–1506 (2005).

Felsenstein, J. PHYLIP: phylogeny inference package (version 3.5c). University of Washington, Seattle (1993).

Schloss, P. D., Larget, B. R. & Handelsman, J. Integration of microbial ecology and statistics: a test to compare gene libraries. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70, 5485–5492 (2004).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) (41076077; 41176127).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ZY and ZL conceived and designed the experiments. ZY performed the experiments. ZY and ZL analyzed the data and wrote the paper.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information

Suppl.Tables S1,S2 and Figures S1, S2

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareALike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, Z., Li, Z. Spatial distribution of prokaryotic symbionts and ammoxidation, denitrifier bacteria in marine sponge Astrosclera willeyana. Sci Rep 2, 528 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep00528

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep00528

This article is cited by

-

Spatial and temporal anoxia in single-osculum Halichondria panicea demosponge explants studied with planar optodes

Marine Biology (2021)

-

Testing the relationship between microbiome composition and flux of carbon and nutrients in Caribbean coral reef sponges

Microbiome (2019)

-

Nitrification in intertidal sponge Cinachyrella cavernosa

Aquatic Ecology (2018)

-

Functional Transcripts Indicate Phylogenetically Diverse Active Ammonia-Scavenging Microbiota in Sympatric Sponges

Marine Biotechnology (2018)

-

Vertical profiles of water and sediment denitrifiers in two plateau freshwater lakes

Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology (2017)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.

mark means the OTU only in the cortex,

mark means the OTU only in the cortex,  mark means the OTU in both cortex and endosome samples. The number inside the parenthesis means the number of sequences within each OTU.

mark means the OTU in both cortex and endosome samples. The number inside the parenthesis means the number of sequences within each OTU.

mark means the OTU only in the endosome. The number inside the parenthesis means the number of sequences within each OTU.

mark means the OTU only in the endosome. The number inside the parenthesis means the number of sequences within each OTU.