Key Points

-

Provides an explanation of oral surgery complexity levels and procedures.

-

Provides an explanation of the proposed oral surgery patient care pathway.

-

Discusses potential solutions to remedy the challenges of implementing the proposed oral surgery commissioning framework.

Abstract

Introduction The Guide for commissioning oral surgery and oral medicine published by NHS England (2015) prescribes the level of complexity of oral surgery and oral medicine investigations and procedures to be carried out within NHS services. These are categorised as Level 1, Level 2, Level 3A and Level 3B. An audit was designed to ascertain the level of oral surgery procedures performed by clinicians of varying experience and qualification working in a large oral surgery department within a major teaching hospital.

Materials and methods Two audit cycles were conducted on retrospective case notes and radiographic review of 100 patient records undergoing dental extractions within the Department of Oral Surgery at King's College Dental Hospital. The set gold standard was: '100% of Level 1 procedures should be performed by dental undergraduates or discharged back to the referring general dental practitioner'. Data were collected and analysed on a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet. The results of the first audit cycle were presented to all clinicians within the department in a formal meeting, recommendations were made and an action plan implemented prior to undertaking a second cycle.

Results The first cycle revealed that 25% of Level 1 procedures met the set gold standard, with Level 2 practitioners performing the majority of Level 1 and Level 2 procedures. The second cycle showed a marked improvement, with 66% of Level 1 procedures meeting the set gold standard.

Conclusion Our audit demonstrates that whilst we were able to achieve an improvement with the set gold standard, several barriers still remain to ensure that patients are treated by the appropriate level of clinician in a secondary care setting. We have used this audit as a foundation upon which to discuss the challenges faced in implementation of the commissioning framework within both primary and secondary dental care and strategies to overcome these challenges, which are likely to be encountered in any NHS care setting in which oral surgery procedures are performed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Guide for commissioning oral surgery and oral medicine1 is a landmark document published by NHS England in September 2015 which prescribes the complexity of oral surgery and oral medicine investigations, procedures and management that should be undertaken by practitioners in both primary and secondary care settings. Whilst the recommendations in the document are not currently enforced, they will in future form the foundation upon which oral surgery and oral medicine services are delivered in England. For the purposes of this article we will discuss this guide in the context of commissioning oral surgery services only.

The commissioning guide divides oral surgery procedures into three levels that reflect a clinician's competence to deliver care of a specific complexity. Level 1 procedures are those that are commissioned to be performed by a clinician with a level of competence as defined by the curriculum for dental foundation training or equivalent training programme. Consequently, these procedures are the minimum expected to be performed within NHS primary dental care services.

Level 2 procedures are those that require a surgeon with enhanced skills due to procedural complexity or modifying patient factors which further complicate treatment. Level 2 procedures may be performed by clinicians who are registered on the General Dental Council's (GDC) specialist list. However, entry on the GDC's specialist register is not an absolute requirement for clinicians who provide Level 2 care. As a result, Level 2 procedures can either be performed in primary or secondary care depending on commissioning patterns.

Level 3A procedures are those which are to be performed by a registered specialist oral surgeon as defined by the GDC criteria or a consultant oral surgeon. Level 3B procedures are those which are to be performed specifically by a consultant and therefore Level 3 procedures will usually be performed in a secondary care setting. The levels of complexity are summarised in Box 1.

A pre-requisite of having obtained a BDS qualification is for all general dental practitioners (GDPs) to have developed clinical skills to a level of competence defined by the curriculum for dental foundation training or an equivalent curriculum. At the very minimum GDPs are expected to acquire the clinical skills required to perform routine non-surgical dental extractions.

The three-year specialty training programme in oral surgery outlines the knowledge, skills and attitudes required to be a specialist in oral surgery. Practitioners who have completed this training pathway and have passed the Tri-Collegiate Membership of Oral Surgery examination may apply for the award of a certificate of completion of specialist training (CCST) and entry onto the GDC's list of specialists in oral surgery.2

Given that the Guide for commissioning oral surgery and oral medicine1 was published relatively recently, there may still be a lack of awareness amongst practitioners in primary and secondary care settings regarding the introduction of the commissioning framework. Consequently, adherence with the new framework may be limited at present. As NHS England seek to streamline care and alleviate time and financial pressures upon secondary care settings, future compliance will need to be improved as the framework will form the basis of commissioning for dental services in oral surgery.

This audit was carried out within the setting of a major teaching hospital and as such there is a responsibility to ensure that all undergraduate students develop the clinical skills as defined by GDC criteria to perform non-surgical dental extractions. The department is part of a wider NHS Foundation Trust with a responsibility to ensure that patients are treated as per the requirements of the 18 week Referral To Treatment (RTT) pathway. Oral surgery cases are triaged in a manner that fulfils both of these obligations and ensures that cases of higher complexity are treated by more experienced members of staff, thereby reducing waiting list times and improving the efficiency of patient care.

Aim

This audit sought to ascertain the compliance with the Guide for commissioning oral surgery and oral medicine1 in a large oral surgery teaching department for the management and treatment of oral surgery cases only and provide an indication of the proportion of Level 1 procedures performed by different levels of practitioner.

Gold standard

The set gold standard was that 100% of Level 1 extractions should be discharged back to the GDP for treatment or performed by the dental undergraduate students to fulfil teaching requirements for the undergraduate oral surgery teaching programme. This ensured that undergraduates would fulfil a sufficient number of quotas required to develop their clinical skills and access to Level 2 and Level 3 practitioners would be improved for those patients requiring more complex treatment.

Materials and methods

A randomised retrospective case note and radiographic review of 100 consecutive patient records undergoing non-surgical and surgical dental extractions within the Department of Oral Surgery at King's College Dental Hospital was performed in April 2016 and July 2016.

Both first and second audit cycles were carried out on patients undergoing treatment under local anaesthetic or intravenous sedation with local anaesthesia only. Procedures performed under general anaesthesia were not included. Cases of all medical complexities were included as were cases treated by all levels of clinicians including undergraduate students. Case selection intentionally excluded all minor oral surgery procedures except non-surgical and surgical tooth extractions.

Case notes were used to determine the level of practitioner by whom the treatment was performed. Where documented, modifying factors were taken into consideration when deciding the level of complexity of each procedure. Both plain film radiographs and cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) scans were used to establish the procedural complexity of each case.

A specialty registrar and a consultant in oral surgery performed the review independently of each other to ensure calibration between the auditors when deciding the level of complexity of each case. Only case notes where there was agreement in the level of complexity between both auditors were included in the audit cycles. Data were entered into a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet for analysis.

The results of the first audit cycle, together with a comprehensive explanation of the commissioning guide were presented in a formal meeting to all clinicians and surgeons within the Department of Oral Surgery at King's College Dental Hospital. An action plan was formulated and recommendations made to improve compliance with the set gold standard.

Subsequently, a second audit cycle was performed three months after the implementation of the action plan. Both the first and second cycles of the audit were performed by the same members of the oral surgery team.

Results

First audit cycle

An overall consensus between both auditors as to whether a procedure was a Level 1, 2 or 3 procedure based upon case note review, radiographic assessment and consideration of modifying factors was achieved in 80 cases (80%). Of these, there was agreement that 54 (67.5%) cases were Level 1 procedures, 17 (21.3%) were Level 2 procedures and nine (11.3%) were Level 3 procedures.

Of the 54 Level 1 procedures, 14 (25%) met the set gold standard. The remaining 40 (74.1%) Level 1 cases were triaged for and treated by Level 2 practitioners. No Level 1 case was treated by a Level 3 practitioner.

Of the 17 Level 2 procedures, 16 (94%) were treated by Level 2 practitioners.

In one instance a Level 2 procedure was triaged to a Level 2 practitioner but treated by a Level 1 practitioner due to service pressures.

Seven of the nine (77%) Level 3 procedures were performed by Level 3 practitioners. The remaining two, whilst triaged to a Level 3 practitioner, were performed by a Level 2 practitioner due to service pressures and teaching requirements.

Second audit cycle

An overall consensus between both auditors as to whether a procedure was a Level 1, 2 or 3 procedure based upon case note review, radiographic assessment and consideration of modifying factors was achieved in 67 cases (67%). Of these, there was agreement that 39 (58.2%) cases were Level 1 procedures, 22 (41.8%) were Level 2 procedures and one (1.5%)was a Level 3 procedure.

Of the 39 Level 1 procedures, 26 (66%) met the set gold standard. The remaining 13 Level 1 cases were triaged to and treated by Level 2 practitioners. No Level 1 case was treated by a Level 3 practitioner.

Of the 22 Level 2 procedures, 20 (90%) were treated by Level 2 practitioners.

In one instance a Level 2 procedure was triaged to a Level 2 practitioner but treated by a Level 1 practitioner due to teaching requirements. The remaining Level 2 case was treated by a Level 3 practitioner due to staff shortages.

The single Level 3 procedure was performed by a Level 3 practitioner.

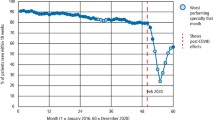

In all cases treatment was performed within the Department of Oral Surgery at King's College Dental Hospital. Level 1 procedures performed by Level 1 practitioners were done so by dental undergraduate students. No patients were discharged back to the referring GDP. These results are summarised in Figure 1.

Action plan and recommendations

The results of the first audit cycle were presented together with a comprehensive explanation of the Guide for commissioning oral surgery and oral medicine1 to all clinicians within the Department of Oral Surgery at King's College Dental Hospital in order to explain the rationale for the audit and improve understanding of the proposed commissioning framework amongst all clinicians working within the department.

The action plan proposed a method to improve calibration amongst all clinicians within the department when deciding the level of complexity of a procedure during outpatient clinic assessment. A specially created calibration tool was devised, comprising of ten cases for which each clinical staff member was asked the level of complexity relating to the clinical and radiographic information provided. The use of this identified a consensus of 70% amongst 46 members of the clinical team. The action plan included the further use of this calibration tool alongside ongoing quarterly re-audit in order to improve adherence with the set gold standard and to address any variance in consensus between clinicians working within the same department.

The auditors recommended that all clinicians should independently familiarise themselves with the Guide for commissioning oral surgery and oral medicine1 in order to develop a better understanding of the importance of triaging cases to the appropriate level of practitioner. Furthermore, it was recommended that each clinician should specify the level of complexity of a case and the associated complicating factors in the clinical notes in order to justify their decision to triage each case to a particular level of practitioner.

Discussion

Description of the complexity levels

The Guide for commissioning oral surgery and oral medicine1 describes the procedural complexity of a case and the corresponding competence of a practitioner to perform a certain procedure. The three levels of complexity do not account for any impact of medical factors affecting the patient, the contract upon which delivery of care is performed, nor the setting in which treatment is performed. Care is delivered by a pathway approach in order to standardise the delivery of oral surgery services throughout England and thereby ensure consistency in the delivery of care.

The summarised patient journey (Fig. 2) published in the guide describes the management of cases of different levels of complexity that present in both primary and secondary care. The implementation of this pathway aims to dissolve the artificial divide between primary and secondary care,1 thereby improving the efficiency of the delivery of care.

Summarised illustrative patient journey (Oral Surgery) from Chief Dental Officer Team, Guide for commissioning oral surgery and oral medicine, NHS England, 20151

As per the guide, there is an expectation for Level 1 procedures to be delivered within any NHS dental primary care contract. Level 2 procedures are those to be managed by a clinician who may or may not be registered on the GDC specialist list for oral surgery but nonetheless have enhanced skills and experience in oral surgery. This may be defined by their years of postgraduate experience in performing oral surgery procedures or formal postgraduate and/or specialist qualifications, the most recognised of which is the completion of the Tri-Collegiate Membership of Oral Surgery examination. Dentists with special interests (DwSI) in oral surgery or accredited practitioners under various NHS pilot schemes are also considered to be Level 2 practitioners. Level 3 procedures may necessitate a multidisciplinary approach or may require specialised facilities and as a result will usually be performed in secondary care settings.

Whilst a procedure may be considered Level 1 on the basis of clinical and radiographic examination, modifying factors may complicate this and thus the overall procedure may instead be considered a Level 2 procedure. These modifying factors may include the following:

-

Complex medical history

-

Social factors

-

Patient anxiety.

For example, a routine non-surgical extraction in a fit and healthy patient would be considered a Level 1 procedure. If the same patient's medical history was complicated by a longstanding medical condition, physical disability or mental health condition, their treatment would be considered to be a Level 2 procedure.

Referral of oral surgery treatment to secondary care

Recent figures suggest that a significant number of referrals to secondary care settings and specialist oral surgery units are for routine dental extractions and for treatment of less complex procedures.3 Despite the small sample size, the results of this audit further support this finding with at least half of all procedures referred to this secondary care unit being of Level 1 complexity.

This results in further pressure upon consultant-led waiting lists which have come under further scrutiny since the introduction of the 18-week RTT pathway. Increased waiting list times further disadvantage those patients with complex treatment who would benefit most from Level 2 and Level 3 care.

Furthermore, referral of Level 1 procedures can also place a financial burden upon the secondary care organisation. Consultant-led departments are obliged to commence the process of treatment for all patients who are referred from primary care within the remit of the 18 week RTT pathway and failure to do so results in a financial penalty. This can be avoided if Level 1 procedures are appropriately managed in primary care.

Referral of oral surgery procedures to teaching hospitals

One notable exception to the prescribed care pathway is that of referral of oral surgery procedures to dental teaching hospitals. Teaching hospitals have a responsibility to provide and maintain a continuous source of patients and procedures of all levels of complexity in order to successfully support clinical teaching of dental undergraduate students, dental core trainees and specialty registrars. As a result teaching hospitals benefit from the acceptance of Level 1 and a greater proportion of Level 2 procedures which may otherwise be treated in primary care in order to fulfil their teaching obligations. However, acceptance of a greater number of Level 1 procedures is only of benefit to a teaching hospital if these referrals are treated by undergraduate students and trainees rather than more experienced clinicians. This audit has demonstrated that over half of the procedures performed in this department were Level 1 procedures. Whilst the first cycle showed that this did not necessarily fulfil teaching obligations, the second audit cycle showed a marked improvement in triaging of patients for treatment by undergraduate students. The poor compliance with the gold standard in the first audit cycle is likely to be reflective of an unfamiliarity with the commissioning guide amongst all members of the team, particularly part-time or locum staff. Consequently, clinicians may have been more amenable to raising their threshold for case selection for undergraduates, especially in light of pressures placed upon them by patients who decline undergraduate treatment.

Patients referred for treatment of a Level 1 procedure should be made aware by the referring GDP that their treatment will be performed by an undergraduate trainee in a teaching hospital setting and not a staff or associate specialist (SAS) grade. Failure to do so will result in an unnecessary delay of treatment for the patient if they refuse undergraduate treatment and are subsequently discharged back to their referring GDP for management.

Whilst teaching hospitals do benefit from access to Level 1 and Level 2 procedures, this is not carte blanche for GDPs to refer all oral surgery procedures for treatment. Patients must be given the choice of where they would like to have their treatment and in the case of Level 1 procedures, whether they would prefer their treatment to be performed by their own GDP in a familiar setting or by a supervised undergraduate student.

Finally, GDPs must remain mindful that many teaching hospitals provide dental emergency and walk-in services which act as an additional source of access to a significant number of Level 1 and Level 2 procedures for teaching undergraduate students and all levels of trainees. Patients accessing these services may not necessarily be registered with a GDP and as such access care on an ad hoc basis for symptomatic treatment.

Challenges of the new model

Services

Ideally, barring the aforementioned exception of referral to teaching hospitals, all Level 1 procedures and a greater proportion of Level 2 procedures should be performed in primary care. Whilst this may ultimately be an achievable goal, the authors are also of the opinion that it is too idealistic to expect such conformity with the commissioning guide at the present time with immediate effect and without the investment of top-up training for those GDPs who may be deskilled or inexperienced. In this audit the set gold standard was not achieved in either the first or second audit cycles due to a combination of challenges in successful adherence to the new commissioning model and we can postulate that these same challenges are faced in both primary and secondary dental care settings throughout NHS services nationally.

The main challenge is most likely to be of awareness of the new model of commissioning amongst both primary and secondary care practitioners. GDPs working under growing time and financial pressures may view referral to secondary care as a means of alleviating some of these pressures. In secondary care, triage of referred Level 1 procedures may be further overlooked by locum practitioners or trainees on rotation, including dental core trainees and postgraduate students. This point is illustrated by the results of the first audit cycle, with 74.1% of Level 1 procedures being performed by Level 2 practitioners.

A solution to remedy this challenge may be through further formal education or top-up training for all practitioners and the availability of guidance or mentoring from more senior and experienced colleagues and consultants. Following the implementation of an action plan the second audit cycle showed a marked improvement in line with the set gold standard. However, the body of competent Level 1, 2 and 3 practitioners already existed within this model. In a primary care setting, consideration needs to be given to increasing awareness of commissioning patterns, improving confidence and providing re-training to enable GDPs to undertake all Level 1 activity.

Whilst the number of Level 1 procedures referred for treatment remained relatively unchanged in this audit, the proportion that were treated by dental undergraduate students significantly increased as a direct consequence of a formal staff meeting in which all team members were educated further on the Guide for commissioning oral surgery and oral medicine1 and its significance within secondary care. This was further reinforced using a specially created calibration tool, the use of which identified an overall consensus of 70% amongst 46 members of the team.

Furthermore, an agreement could not be reached between the two auditors regarding the level of complexity in 20% of cases in the first cycle. If an agreement could not be reached between two individuals, it is unrealistic to expect a complete consensus within any secondary care department. This provides further explanation as to why the set gold standard was not achieved in the second cycle even after an action plan was formulated and delivered. Inter-operator variance, both in primary and secondary care, is therefore likely to remain an ongoing challenge in achieving any such gold standard and should be reflected in future commissioning patterns.

In a teaching hospital, consideration of unpredictable factors such as staff sickness and clinical tutor absence may unavoidably result in reallocation of patients to prevent delay in provision of treatment. Subsequently, this may result in Level 1 procedures which would ordinarily be performed by supervised undergraduate students being performed by Level 2 practitioners. Commissioners will need to accommodate for this margin of error when negotiating future primary and secondary care oral surgery contracts.

It is not uncommon to encounter patients who are insistent upon specialist or consultant care even if their treatment can be readily performed by a non-specialist in primary care. Under the time constraints of outpatient clinics it is too idealistic to expect all clinicians not to yield to such pressure, particularly if they are junior or less experienced members of the team. To address this, GDPs and secondary care practitioners should encourage patients, through an informed discussion, of the benefits of shorter waiting times and continuity of care if their treatment can be performed by Level 1 practitioners in a familiar and locally accessible setting. As the commissioning guide reflects future contractual agreements, referral to a secondary care setting for Level 1 procedures will require a verbal understanding between the GDP and patient that treatment will be exclusively carried out by dental undergraduate students or referred back for management in primary care should this be deemed unacceptable by the patient.

This audit has demonstrated that up to 60% of procedures performed in the department were Level 2 procedures performed by specialists and dentists with enhanced skills and experience. Clinicians who are not specialists but have enhanced skills in oral surgery can perform Level 2 procedures in primary care depending on national commissioning arrangements. Future commissioning patterns may reflect this to increase access for specialist services in primary care, thereby improving overall access and in turn reducing waiting times.

Currently, GDPs are under a number of hidden pressures including limited clinical time, greater patient demands and increased litigation. These factors, combined with a potential lack of experience, may drive the current trend in increased number of referrals for Level 1 cases to secondary care for treatment. Whilst the commissioning guide has paved the way for all Level 1 activity to be performed in primary care, commissioners are yet to address the lack of oral surgery training courses aiming to refresh and enhance oral surgery skills for the GDP. Successful implementation of the commissioning guide will rely on upskilling Level 1 practitioners in primary care with further ongoing investment in training or CPD courses.

At present no defined national pathway exists for accreditation as a Level 2 practitioner, although a number of pilot schemes are paving the way for this in the future. This, combined with the relatively few accredited oral surgery teaching courses, poses a challenge to those GDPs with enhanced skills and experience seeking such accreditation. A solution for national accreditation through a robust process will further increase the provision of oral surgery services in primary care and improve adherence with proposed commissioning framework.

Conclusion

The Guide for commissioning oral surgery and oral medicine1 sets out a framework for oral surgery services to be delivered in a more efficient and financially viable manner. This audit provides a basis from which one can assess the nature of the challenges faced in implementing the guide within a secondary care setting and discusses the challenges that may be faced in primary care. Through greater education for both clinicians and patients, these challenges can be overcome to achieve greater continuity and familiarity of care for patients accessing NHS oral surgery services.

References

Chief Dental Officer Team. Guide for commissioning for oral surgery and oral medicine. London: NHS England, 2015.

Specialty Advisory Committee for Oral Surgery. Specialty Training Curriculum – Oral Surgery. London: Faculty of Dental Surgery, 2014.

Coulthard P, Kazakou I, Koron R, Worthington H V . Oral Surgery: Referral patterns and the referral system for oral surgery care. Part 1: General dental practitioner referral patterns. Br Dent J 2000; 188: 142–145.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed Paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Modgill, O., Shah, A. Compliance with the guide for commissioning oral surgery: an audit and discussion. Br Dent J 223, 509–514 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2017.838

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2017.838

This article is cited by

-

Guide for commissioning oral surgery: the development of a calibration tool

British Dental Journal (2020)

-

Modelling clinical decision-making in triage of referrals for extraction

British Dental Journal (2019)

-

Initial periodontal therapy before referring a patient: an audit

British Dental Journal (2019)