Key Points

-

Delves deep into students' motivation to become clinicians.

-

Describes students' own experiences of stress in their undergraduate programmes.

-

Puts forward a more optimistic view of the role of stress in dental undergraduate training.

Abstract

Aims To use a qualitative approach to further explore the stress and well-being of dental hygiene and dental therapy students (DHDTS) during their undergraduate training.

Subjects and methods Semi-structured individual interviews to explore motivation, goals, and perceived stress, were conducted with eight DHDTS from across all three years of study at the University of Portsmouth Dental Academy (UPDA). Thematic analysis of the data was undertaken using Braun and Clarke's (2006) six phases of thematic analysis.

Results Three main themes of 'fulfilment', 'the learning environment', and 'perception of stress' were identified. Within these themes, a further 12 sub-themes were identified. Analysis suggested that a strong sense of passion to become a clinician mitigated most, but not all, of the stressful experiences of the DHDTS undergraduate learning environment.

Conclusions DHDTS' perceived sources of stress during their undergraduate programme were strongly linked to a sense of meaningfulness.

Listen to the author talk about the key findings in this paper in the associated video abstract. Available in the supplementary information online and on the BDJ Youtube channel via http://go.nature.com/bdjyoutube

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Research has predominantly used the Dental Environment Stress (DES)1 questionnaire to explore perceived sources of stress in dental undergraduate students.2,3,4 However, there are gaps in the literature when it comes to exploring stress among other members of the dental team, for example dental hygiene and dental therapy students (DHDTS), who are educated in a similar environment to dental undergraduate students.5 Most studies exploring dental student stress have equated psychological well-being with the presence or absence of stress, or psychological disorders such as depression.6,7,8 However, studies have also shown that there are multiple dimensions which contribute to a sense of positive psychological well-being. This body of knowledge suggests that positively-functioning individuals establish goals, direction, and purpose, which give them a sense of meaning in life.9,10

A recent study11 suggested that a stressful life can also be a meaningful life where the stress of pursuing goals feeds a sense of purpose. Linked to this, the study further suggested that individuals often will accept short-term costs, for example pain, anxiety and stress, in order to come out better in the long run. Subsequent research12 further supported this, and concluded that stress should not be seen as a weakness, but as a sign that something you care about is at stake. The literature also states that how the stress is appraised by an individual defines whether it is perceived as a challenge (enhancing) or a threat (debilitating).12,13,14

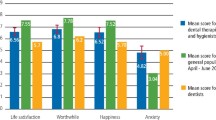

Another recent study15 used valid and reliable measures of well-being9,10,16in conjunction with the widely-used DES to explore stress and well-being in DHDTS. This study showed that DHDTS reported similar levels of stress to that of dental students. However, the DHDTS, unlike the dental students, also reported high scores in the psychological well-being dimensions associated with meaning; more specifically, goals, purpose in life, personal growth, and valued living.9,10,16 The findings of this research, which provided baseline data on student stress and well-being, provided the stimulus for this qualitative follow-on study.

Valued living is described as the successful consequence of meaningful goal pursuit that is intrinsically reinforced, and serves an individual's core values.16,17 Using the compass as a metaphor, values have been described as the direction of travel, and goals as the weigh-points that help individuals move in that direction.17 For example, an individual may have a core value of making a difference to society, and choose a career (goal) as a health care professional, which serves that value. Living a valued life requires the successful balance of aligning our goals and values across all of the different domains of life, so that over-prioritising activities which serves one value is not to the detriment of other personal values (for example, work-life balance).17,18

In the past, stress and well-being in the dental undergraduate programme has primarily been examined using quantitative methodology.3,4 Furthermore, the literature has revealed little new knowledge in the results and conclusions of studies over the last three decades.1,2,3,4 The need for further enquiry into this field, and the qualitative approach adopted within the current research, which captures students' experiences of stress and well-being from their own perspectives, rather than imposing pre-defined theoretical categories to simulate their experience of the world, is thus indicated. Indeed, a qualitative approach may provide a new opportunity to recognise phenomena (for example, meaning), that has previously been omitted by researchers' reliance on quantitative methodology.

Against this background, the aim of this study was to develop further our shared understanding of stress and well-being in the dental learning environment. Building on the former body of knowledge and earlier quantitative research, it qualitatively explores these considerations with one student community of DHDTS undertaking their training at the University of Portsmouth Dental Academy (UPDA).

Methods

Ethical approval was gained from the University of Portsmouth Science Faculty Ethics Committee (SFEC 2016–052). Participants were advised verbally and in writing, that all information they provided was confidential and that their data would be anonymised. They were given the interview schedule four days before the interview to ensure that consent to participate in a recorded interview was both informed and valid. A convenience sample of eight DHDTS from UPDA (11% of total student population), who had provided their email address to be contacted for a follow-up interview after completion of an online survey, were recruited to participate in semi-structured interviews of approximately 45 minutes duration. The participants were from Years 1 (N = 1), 2 (N = 5), and 3 (N = 2) of the BSc (Hons) in Dental Hygiene and Therapy, to ensure that their experiences reflected the undergraduate programme in its entirety. The interviews were conducted by the first author (MH), who was not actively involved in their education. Seven of the interviews were conducted in a small meeting room at UPDA, which was the preferred venue for the participants. One interview was conducted by telephone. All of the interviews were conducted in July 2016, after the results of the annual examinations. All of the participants were female.

Data collection

An interview schedule designed to explore perceived motivation, goals (in particular, goal failure) and stress in DHDTS, was piloted on two former students, and adapted in light of their feedback. The study participants were firstly asked to talk about their motivation to study dental hygiene and therapy. A second block of questions asked about their perceived causes of stressful experiences within the learning environment (for example, handling goal failure as well as criticism of their work); as identified from previous work and the literature. For example, participants were asked, 'we all fail to get all of our goals sometimes; what do you do if this happens to you?' and 'how do you deal with being observed and having your performance with patients assessed and graded?' The third block of questions was designed to explore the perceptions of stress within the learning environment as enhancing or debilitating.

Analysis

Interview transcriptions were sent to the participants, who were asked to confirm their accuracy before the analysis was carried out. Thematic analysis of the data was undertaken using Braun and Clarke's (2006) six phases of thematic analysis: 1. Familiarising oneself with the data; 2. Generating initial codes; 3. Searching for themes; 4. Reviewing themes; 5. Defining and naming themes; 6. Producing the report.19 The recorded interviews were manually transcribed as it is 'a key phase of data analysis within interpretative qualitative methodology', and as an approach was considered an excellent way for the researcher to become immersed within the data.20 Initial codes were generated from across the entire data set and then collated into potential themes. These themes were then reviewed and further defined, and named. Twenty-five percent of the data were analysed independently by the two second authors experienced in qualitative methodology (JCW and DRR), and three themes encompassing twelve sub-themes were identified.

Results

Table 1 shows the three themes and 12 sub-themes developed from the data.

Analysis of these themes suggested that the strong sense of passion to become a clinician mitigated most, but not all, of the stressful experiences of the dental learning environment.

In the first theme labelled fulfilment, the participants described their motivation for becoming a DHDT. Within the data the first sub-theme of an unfulfilled past emerged. Here participants expressed an overwhelming desire to feel needed and be trained for a profession which they felt made a difference to people's lives.

Six out of the eight participants had been dental nurses in the past. However, there was a distinct sense of lack of fulfilment, and even frustration at their restricted involvement in patient care in that role. For example, one participant described herself as 'reaching a ceiling' as a dental nurse. Another, reflecting on the lack of utilisation of additional skills that she had hoped would have expanded her role as a dental nurse, stated:

'I did an oral health education course and really liked the patient contact. I liked working at that level, which being an assistant [sic dental nurse] didn't allow' (SS1).

In the second sub-theme, 'enjoying the present', the degree programme itself was a source of fulfilment for all of the participants. The mature students, who had been away from formal education, described the programme as an opportunity to realise they were more academically capable than they had previously given themselves credit for. On the other hand, the younger participants who had progressed directly from A level studies, discussed their sense of fulfilment from the acquisition of life skills that the programme promoted:

'I feel more confident talking to people that I don't know. Like at first, I was a bit nervous – my communication skills weren't as good as what they are now and they've really improved, and that benefits me outside of Uni [sic University] as well' (SS4).

In the third sub-theme of 'expecting to be helpful and useful in the future', participants described how responsibility, patient engagement, and making a difference were key motivators to their perception of their future roles as DHDTS. The majority described their desire to 'help patients more directly' and 'be in the driving seat'. This sense of purpose was particularly strong for one participant who stated:

'Thinking you only get a limited time doing what you're doing and knowing that you have some sort of a contribution to society, someone else's life, it's not just waking up and doing what you're supposed to do'(SS8).

Another participant also valued the flexibility of her future job role in relation to the potential of a good work-family balance:

'I knew that hygiene and therapy is something that you can do part-time or full-time and often people do work part time in different practices, because as a woman in the future at some point a family is something that I would probably consider and it's quite nice that that it is a career that would adapt around that' (SS3).

In the second theme, labelled 'the learning environment', participants described their experiences of teaching and learning at UPDA. In the first sub-theme, labelled 'learning from peers', participants identified peer learning as a fundamental aspect of their progression through the programme. The majority of participants described how they enjoyed being part of larger peer-learning networks within their cohort, while a small minority relied on one or two significant others. Some participants also described maximising opportunities to learn from others outside of the university while they were undertaking paid work. One participant who was working as an agency dental nurse at weekends, stated:

'Just watching clinicians work and letting them know that I'm on this course. They've been really helpful in showing me things and giving me tips along the way. Just shadowing them and just seeing how they work and how it's kind of natural to them' (SS7).

Participants also identified peer support to be as equally important as peer learning:

'It's quite nice when you do talk to others and they say “yes, it happened to me last week” because you can feel very on your own. It's not until you all sit down and talk to each other that you realise that others feel the same. If you didn't have anyone to speak to, peer wise, you'd go a bit mad, I think. It's nice to be able to talk and realise that you're not alone' (SS2).

In the sub-theme 'differing feedback', all participants discussed the various ways that they learnt from tutors. However, there were mixed opinions in relation to dealing with the differing advice received from the clinical teaching staff. Some participants found it more difficult to accept conflicting advice than others, with one participant stating:

'It's very difficult if you have maybe the same patient and two appointments with them, and the first one someone tells you to do something and you get to the second appointment and a different tutor will say something different. It means that you struggle at the start to actually figure which is the right answer and then eventually as time goes on I think you find your own answer' (SS3).

Whereas the majority of participants felt that conflicting opinions reflected the reality of what it will be like in practice:

'In practice, everyone is different and as a clinician, so you're not stagnant just having one person's opinion, you have lots of different opinions which is good' (SS2).

'Everyone has different experiences – everyone has a different job and has trained in different areas. Although there are text-book answers, every clinician has a slightly different take on things. To be a well-rounded learner you need to have different opinions from different people. If you have only one view all of the time, then you don't learn different ways of looking or approaching things' (SS1).

In the third sub-theme, negative feedback was perceived as a necessary evil to learn from and develop. Most interviewees described negative feedback as 'not pleasant' or sometimes 'disappointing', with some participants describing how they 'beat themselves up', but then viewed it as a challenge:

'No-one likes negative feedback, I get quite a bit disappointed, but I think I need that to be able to learn to be able to progress. I beat myself up at first, but come out the other end. I think right, OK, then as a challenge, how am I going to make sure this doesn't happen next time? Or how can I change it to be better' (SS2).

'Initially it's not pleasant, but I think you definitely do just get used to it. It's not pleasant, but that is the best way. As a learning experience, if you're not being observed and graded then you're not going to learn or improve' (SS5).

Unsurprisingly, in the fourth sub-theme, 'examinations as barometer of current capabilities', all participants identified successfully passing the programme as their long-term goal. Passing examinations were perceived to be a 'barometer' to show their capabilities to themselves and others in the establishment:

'I enjoy exams, which is a little bit strange because it's kind of a marker to show what I can do. I feel like you spend all year working really hard, and if it was just tick boxes and didn't have those exams, you wouldn't be able to realise not only your potential, but others wouldn't realise it either'(SS6).

Some of the participants described how examination success in one year 'pushed' them to think about making it better for the next time, as one participant said:

'When I got my marks each year, I would think how can I make that better for next time' (SS1).

Interestingly, the sub-theme, 'examinations as failed attempts to measure capabilities', revealed how a minority of interviewees felt somewhat 'cheated' by the examination process itself. One participant quite bluntly stated:

'I felt like I wasn't showing off my true ability in those exams, because I revised a lot more and did a lot more revision compared to other people who didn't revise all the topics. I felt my revision wasn't reflected in those exams' (SS4).

In the penultimate sub theme, 'accepting failure as part of learning', the majority of participants identified goal failure as something that they accepted as part of being a student. For one participant, goal failure was described as a tool to aid resilience, whereas another described it as a form of self-acceptance:

'I think there's nothing constructive that ever happens from just being negative about something – if you keep trying, what doesn't kill you, makes you stronger, more resilient. If something really doesn't happen, maybe it wasn't meant to be. If you keep saying no in one field, maybe go another path; pave your own way' (SS8).

'I kind of don't expect everything to go perfect; I tend to just deal with things as they happen. When I first started revising I thought OK, I'm going to work as hard as I can, but if I have to retake, I'll have to retake; I didn't think that I'm going to get this first time, it might take a few goes, but I will get there eventually'(SS7).

'Rejecting failure', which was the final sub-theme, showed how for a minority of participants, goal failure was difficult to accept:

'I don't like it when things go wrong. I don't like to accept it. I want everything to be perfect. At the time, I keep thinking about it, like why did I do that? It's when I go home I realise then OK. Once I go home and realise what's happened – that's when it sinks in and that's when .... aah, I could have done this, when I didn't' (SS4).

Data for the final theme, labelled 'Perception of stress', emerged from responses by participants when they were asked how they physiologically reacted to stressors within the learning environment (examinations, feedback, and goal failure). Most participants described symptoms such as 'shaky hands', 'sweating', and an overarching worry to 'not let the patient know' that they were anxious.

In the first of the two sub-themes, 'negative perceptions of stress', the majority of students perceived the physiological symptoms of stress to affect their performance in a negative way:

'I do feel like it did affect me. Whereas if I didn't have those nerves, because I knew what I was doing, it was all in my mind, it just didn't come out that way because I felt nervous' (SS6).

'That initial feeling before you go into an exam, especially a practical exam was just horrible – it's not healthy at all, but I think that once you're in the exam, you kind of relax and everything just flows, but that initial horrible feeling before you go in to an exam, I just think is really unhealthy, and doesn't do anybody any good' (SS2).

In the second sub-theme, 'stress as enhancing', a small minority of students described the physiological symptoms as either enhancing their performance or as a challenge:

'At first I get nervous and then it kind of makes me write quicker – the adrenaline. I don't think it affects my knowledge – it's still in my mind – I've never had a mind blank from being nervous, it's just not a nice feeling' (SS4).

'It's that feeling in your stomach, it's that scared, horrible feeling and I get it with presentations – right before. They're just temporary things, because of something – you know why you're feeling that and in a way, it's good – you just feel human; they're not a bad thing – it's good to be put under stress for a bit to see how you cope with it' (SS7).

Discussion

The findings of this study suggested that the majority of participants derived a sense of fulfilment from aspects of their undergraduate programme that they perceived as stressful. The participants described a strong sense of purpose, where their current experiences of the undergraduate programme were understood within the context of their ambition to be future clinicians.11,21,22Although all the participants described their objective goal as passing the degree programme, many also described a subjective state of fulfilment that undertaking the programme provided. This is consistent with the literature which suggests that it is often the journey to the goal which may be more meaningful than its attainment. What is more, individuals who achieve desirable end states will often form new goals as a means of maintaining a sense of purpose.23,24

Motivation to become a dental hygienist and therapist served the values which the participants reported as around 'wanting to make a difference' and 'being needed'. Moreover, the clinical elements of the programme which involved treating patients as a student, meant that the participants were able to portray current valued living as learners, as well as envisaging a valued life as future clinicians.21,22 Furthermore, the subjective belief that they could actually make a difference, meant that participants in this study also demonstrated a sense of efficacy, which in addition to self-worth, purpose, and values, is one of the four levels of meaning described by Baumeister and Vohs (2005).21

Self-acceptance of criticism of one's work requires the motivation to endure the stress of receiving (negative) feedback in exchange for the learning opportunity of receiving it.25 Indeed, participants in this study highlighted aspects of the learning environment that were difficult, negative, and disappointing. However, most participants showed their maturity and discussed how they utilised the feedback as an opportunity to learn and grow, even where there were instances of conflicting opinions from faculty (the clinical teaching staff). Additionally, 'beating themselves up' also highlighted the issue that some participants reported a lack of self-compassion and found it difficult to take the perspective on their experiences as simply a part of being a student.17 More specifically, these participants tended to set the level of expectation for themselves within the context of that of a qualified clinician, rather than the level of a learner.

Goal attainment is central to Snyder et al.'s (1991) theory of hope.24 Specifically, hope is defined as 'the process of thinking about one's goals, along with the motivation to move towards those goals (agency), and the ways to achieve those goals (pathways),' regardless of the ease or the difficulty of obtaining them.26,27 Studies have shown that students can sustain their motivation by utilising goal setting as a challenge for high academic achievement, even under circumstances of stress.26,28 Indeed, a number of participants described how positive emotions from successful attainment of yearly examinations, encouraged them to set 'stretch goals'24 for higher academic achievement for the next year. On the other hand, some participants reported how reflecting on failed goal attempts led them to alter their pathway to goal pursuit. This is in line with the literature that showed that 'high hope' individuals have the ability to 'let go' of problematic goals. Moreover, they expect mistakes to happen, and do not question their innate talent, but rather conclude that in this case, they did not use the best strategy. They will replace failed goals with either new goals completely, or new pathways for the same goal.27 Snyder et al. (1991) have also described a 'high-hope' individual as someone whose repertoire of goal pursuit contains learning goals as well as performance goals.24,26 However, the majority of participants in this study tended to report goal setting in relation to the more long-term goals of passing the end of year examinations (performance goals). This is not surprising as Western culture puts great emphasis on students getting good grades rather than the process of learning (learning goals).17 Likewise, the literature suggests that 'competition for grades' is one of the high sources of stress in dental student undergraduate training.3,4

Although stress can and does pose a threat to health and well-being, recent research has suggested that stress can also be enhancing.12 Studies have shown that subtle differentiations of mindset can engender meaningful changes in an individual's psychological and physiological state.12,25 More specifically, it has suggested the more an individual adopts a 'stress is enhancing' mind-set, the more likely that stress will have an enhancing effects on their health, performance, and well-being. Conversely, if one views stress as debilitating, the stress is likely to have a deteriorating effect.25

Most of the participants in this study perceived stress as affecting their performance in a negative way. This is not considered surprising as individuals are typically encouraged to avoid stressful situations whenever possible, or actively control unavoidable or inevitable stress.25 Furthermore, the participants attempts to control unavoidable stress, paradoxically resulted in increased anxiety which they perceived affected their performance, and perpetuated the mindset that stress was debilitating. On the other hand, the minority of participants who described a stress enhancing and enabling mindset, suggested that stress enabled them to write quicker in examinations. This group also described examinations as a basis for reward and challenge.

A number of the subthemes identified reflected the notion of belongingness. This included 'expecting to be helpful and useful in the future', 'supporting and learning from peers', and 'accepting failure as part of learning'. As well as the literature which has shown the importance of belongingness in relation to the needs for meaning in life,29 belongingness in dental education has been defined as:

'A deeply personal and contextually mediated experience in which a student becomes an essential and respected part of the dental educational environment where all are accepted and equally valued by each other and which allows each individual student to develop autonomy, self-reflection and self-actualisation as a clinician.'30

Indeed, the DHDT students in this study certainly expressed notions of developing autonomy, self-reflection, and self-actualisation as members of the profession.

Most research on dental student stress has focused on the negative aspects of stress.3,4 This has resulted in some researchers advocating a curriculum change to reduce stress in the dental undergraduate programme.6,31,32,33 However, stress often results from activities that are meaningful, and reducing stress may result in reducing the meaning of the activity.11,12,21,22 Indeed, this study has shown that participants' perceived sources of stress in their undergraduate programme were very strongly linked to meaningfulness, therefore we would argue that reducing the sources of stress in the undergraduate programme may also reduce the meaningfulness of the course. Rather than introducing curriculum change, the researchers in this study recommend interventions to raise awareness of the meaningful relationship of stress as a coping mechanism to build resiliency.25

Within the limits of the study, it confirmed the notion found in existing literature which has associated stress in life with meaningfulness. However, while this study has offered some further insights into stress and well-being among DHDTS, some caution is required. The interview data were drawn from a relatively small sample. While it may be argued that this is consistent with qualitative research approaches described within the literature, the generalisability of the findings and conclusions drawn here to other situations and contexts must be determined by the reader.

Conclusions

This study has provided further understanding of stress and well-being in the dental learning environment. It has also provided new insight and a richer understanding of the previous quantitative study, in which DHDTS reported to be positively functioning individuals at the same time as perceiving their training to be highly stressful.15 Indeed, as the findings of this study were comparable with the findings of the previous quantitative study of the same student cohort, the authors contend that it has provided further evidence of the meaningful nature of stress in dental hygiene and dental therapy undergraduate education.

References

Garbee W H, Zucker S B, Selby G R . Perceived sources of stress among dental students. J Am Dent Assoc 1980; 100: 853–857.

Al-Samadani K H, Al-Dharrab A . The perception of stress among clinical dental students. World J Dent 2013; 4: 24–28.

Alzahem A M, Alaujan A H, Van der Molen H T, Schmidt H G, Zamakhshary M H . Stress among dental students: a systematic review. Eur J Dent Educ 2011; 15: 8–18.

Elani H W, Allison P J, Kumar R A et al. A systematic review of stress in dental students. J Dent Educ 2014; 78: 226–242.

Gordon N A, Rayner C A, Wilson V J, Crombie K, Shaikh A B, Yasin-Harnekar S . Perceived stressors of oral hygiene students in the dental environment. Afr J Hlth Prof Educ 2016; 8: 20–24.

Silverstein S T, Kritz-Silverstein D . A longitudinal study of stress in first-year dental students. J Dent Educ 2010; 74: 836–848.

Laurence B, Williams C, Eiland D . Depressive symptoms, stress, and social support among dental students at a historically black college and university. J American College Hlth 2009; 58: 65–63.

Abu-Ghazaleh S B, Rajab L D, Sonbol H N . Psychological stress among dental students at the University of Jordan. J Dent Educ 2011; 75: 1107–1114.

Ryff C D . Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. J Pers Soc Psychol 1989a; 57: 1069–1081.

Ryff C D . Beyond Ponce de Leon and life satisfaction: new directions in quest of successful ageing. Int J Behav Develop 1989b; 12: 35–55.

Baumeister R F, Vohs K D, Aaker J L, Gabinskey E N . Some key differences between a happy life and a meaningful life. J Pos Psychol 2013; 8: 505–516.

McGonigal K . The upside of stress. London: Vermilion, 2015.

Jamieson J P, Mendes W B, Nock M K . Improving acute stress responses: the power of reappraisal. Current Directions Psychol Sci 2013; 22: 51–56.

Jamieson J P, Nock, M K, Mendes W B . Mind over matter: reappraising arousal improves cardiovascular and cognitive responses to stress. J Exp Psychol Gen 2012; 141: 417–422.

Harris M, Wilson J C, Homes S, Radford D R . Perceived stress and well-being among dental hygiene and dental therapy students. Br Dent J 2017; 222: 101–106.

Smout M, Davies M, Burns N, Christie A . Development of the valuing questionnaire (VQ). J Context Behav Sci 2014; 3: 164–172.

Dahl J C, Plumb J C, Stewart I, Lungdren T . The art and science of valuing in psychotherapy: Helping clients discover, explore, and commit to valued action using acceptance and commitment therapy. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger, 2009.

Aube J, Fleury J, Smetana J . Changes in women's roles: Impact on and social policy implications for the mental health of women and children. Develop Psychopath 2000; 12: 633–656.

Braun V, Clarke V . Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 2006; 3: 77–101.

Bird C M . How I stopped dreading and learned to love transcription. Qual Inq 2005; 11: 226–248.

Baumeister F, Vohs D . The pursuit of meaningfulness in life. In C R Snyder and S J Lopez (eds) Handbook of positive psychology. pp 608–618. New York: Oxford University Press, 2005.

Feldman D B, Snyder C R . Hope and the meaningful life: Theoretical and empirical associations between goal-directed thinking and life meaning. J Soc Clin Psychol 2005; 24: 401–421.

Sommer K L, Baumeister R F, Stillman T F . The construction of meaning from life events: empirical studies of personal narratives. In P T Wong (ed) The human quest for meaning: Theories, research and applications. pp 297–314. New York: Routledge, 2012.

Snyder C R, Harris C, Anderson J R et al. The will and the ways: development and validation of an individual-differences measure of hope. J Pers Soc Psychol 1991; 60: 570–585.

Crum A J, Salovey P, Achor S . Rethinking stress: The role of mindsets in determining the stress response. J Pers Soc Psychol 2013; 104: 716–733.

Snyder C R . Conceptualising, measuring, and nurturing hope. J Couns Dev 1995; 73: 355–360.

Snyder C R, Cheavens J, Sympson S C . Hope: an individual motive for social commerce. Group Dynamics 1997; 1: 107–118.

Snyder C R, Shorey H S, Cheavens J, Mann Pulvers K, Adams V H, Wiklund C . Hope and academic success in college. J Educ Psychol 2002; 4: 820–826.

Stillman T F, Baumeister R F . Uncertainty, belongingness, and four needs for meaning. Psychol Inq 2009; 20: 249–251.

Radford D R, Hellyer P . Belongingness in dental undergraduate education. Br Dent J 2016; 10: 539–543.

Naidu R S, Adams J S, Simeon D, Persad S . Sources of stress and psychological disturbance among dental students in the West Indies. J Dent Educ 2002; 66: 1021–1030.

Divaris K, Barlow P J, Chendea S A et al. The academic environment; the students' perspective. Eur J Dent Educ 2008; 12: 120–130.

Polychronopoulou A, Divaris K . Dental students' perceived sources of stress: A multi-country study. J Dent Educ 2009; 73: 631–639.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed Paper

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Harris, M., Wilson, J., Hughes, S. et al. Does stress in a dental hygiene and dental therapy undergraduate programme contribute to a sense of well-being in the students?. Br Dent J 223, 22–26 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2017.584

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2017.584