Key Points

-

Discusses primary care oral surgery tariffs in England and Wales.

-

Discusses contract types in primary care oral surgery in England and Wales.

-

Includes evidence-based recommendations for standardisation of primary care oral surgery contracts and tariffs.

Abstract

Primary care oral surgery services vary markedly throughout the country but until now there has been a paucity of data on these services. The British Association of Oral Surgeons (BAOS) primary care group (the authors) were tasked to gather data around primary care oral surgery contracts and tariffs and provide evidence-based recommendations on the commissioning of these services. Following a freedom of information (FOI) request, data were obtained for 27 English local area teams and seven Welsh local health boards. The data demonstrated both regional and national variability with respect to primary care oral surgery contracts, concerning both contract type and level of remuneration. These differences are discussed and the authors make recommendations for standardising oral surgery contracts and tariffs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

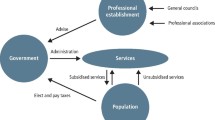

The Medical Education England Review of oral surgery services and training published in 2010 recommended the expansion and development of commissioning of primary care oral surgery (PCOS) services to better serve local need. It concluded 'there is considerable support for the expansion and extension of OS services in the primary care setting to support local delivery of services.'1 While some areas had already successfully commissioned services,2,3 the increase and development of PCOS followed this review.

The aspirations of this document have been expanded upon in the Guide for commissioning oral surgery and oral medicine4 which was published in 2015. This guide describes the direction required to commission oral surgery services in primary care using a consistent and coherent approach. Further work on the implementation of this guide is ongoing.

The BAOS became aware that there was considerable variation nationally in both the type of contracts being awarded and in the level of remuneration made available. Disappointingly, high quality national data on these contracts was not easily accessible. BAOS was invited by the Chief Dental Officer, Sara Hurley, to provide evidence-based recommendations around the commissioning of oral surgery services to assist with implementation of the visions set out in the commissioning guide.

Materials and methods

The BAOS primary care group (the authors) formulated a request for disclosure of data relating to primary care oral surgery contracts in accordance with the Freedom of Information Act.5 This was submitted to every area team (the local dental commissioning arms of NHS England) and to their Welsh equivalents (health boards).

This very detailed request was refused by NHS England under Section 12 of the Act5 as they estimated that the cost of compliance would exceed the prescribed limit of eighteen hours of administration time. Following further discussions with the freedom of information team the request was modified (see Box 1) and resubmitted. Data were ultimately received for 27 English local area teams (LATs) and seven Welsh local health boards (LHBs).

In addition to this data, the accounts of an urban practice holding a regional oral surgery contract was analysed to provide data on the cost of establishing and running a stand-alone primary care oral surgery service.

Results

The figures for the total commissioned activity for primary care oral surgery (PCOS) for 27 English LATs and seven Welsh LHBs are shown in Table 1. Some of the English data were grouped into regions (shown in the first column). The second column details the LATs in each region. Columns three and four show the total spend on oral surgery commissioned and the population per region.6,7 The last column shows the regional oral surgery spend per head of population which varies from £0.12 in Lancashire and Greater Manchester to £1.75 in Hertfordshire and South Midlands.

Four out of the seven Welsh LHBs who replied commission oral surgery services (Cwm Taf, Powys and Betsi Cadwallader do not). The figure for Cardiff and Vale is improbably high and is most likely to include secondary care services. Attempts to clarify the correct figure have been unsuccessful.

If Cardiff and Vale is excluded, the total PCOS spend of the 27 LATs and three LHBs (19 regions) ranges from just under £200,000 (Shropshire and Staffordshire) to just over £4.5 million (Hertfordshire & South Midlands). The total commissioned activity is just under £49 million with a mean spend of £2.7 million.

The data showed that there are two main contracts offered – primary dental service (PDS) contracts based around units of dental activity (UDA) and service level agreements (SLAs).

Eight regions (five English and three Welsh) run PDS contracts with a mean UDA value across all respondents of £60. The value was highly variable, ranging from £20 in Cardiff and Vale to £99 in Yorkshire and Humber (Fig. 1). Additionally, four out of eight regions demonstrated considerable intra-regional variation. Information on the number of UDAs per course of treatment was not available (although the norm is three, this cannot be assumed). Aneurin Bevin and ABMU boards only commission PDS contracts (Cardiff and Vale also commission PDS contracts and may commission SLA contracts but this is unclear from their data) while the five others provide services under a mixture of PDS and SLAs.

Figure 2 shows the 17 regions that commission SLA contracts and the assessment fees paid. These range from £30 (London) to £100 (Hywel Dda). Three regions appear to pay nothing for an assessment visit.

SLA fees for treatment with local anaesthesia alone, from the same 17 regions, are shown in Figure 3. The mean fee across all respondents was £199. These are again very variable (from £100 in South Central to £546 in Lancashire and Greater Manchester). Some of these fees may include assessment within the fee.

Figure 4 shows SLA fees for the 14 out of 17 regions that commission treatment with local anaesthetic and sedation. The mean fee across all respondents was £277. Once again, the tariffs are highly variable (from £112 in London to £621 in Yorkshire and Humber).

One region (Yorkshire and Humber) responded to the request with a very detailed 'fee per item' tariff, which is reproduced in Table 2. This is given to ten out of 21 PCOS providers in the region. The remaining 11 providers command tariffs varying from £120–£225 per procedure, including sedation.

Table 3 shows the 2013/2014 profit/loss for an urban stand-alone single surgery OS practice in the North East of England. The bottom-line profit is 7.6%.

Discussion

The data received from the freedom of information request provides a valuable national picture of how variable the PCOS commissioning landscape is. The complexity of different contract types and the challenge of even defining the boundaries of primary and secondary care mean some figures should be interpreted with caution. This was illustrated by the Cardiff and Vale response, which appears to be an outlier and is very likely to include secondary care spend. Despite this, the huge differences in remuneration for providers were clearly evident and cannot be accounted for by the geographically variable cost of providing the service, especially in light of substantial variation within the LAT or LHB regions. The best example of intra-regional variability was Yorkshire and Humber where ten out of 21 providers in the region receive a fairly complex 'fee per item' tariff (Table 2) while the remainder are on considerably variable PDS and SLA tariffs. This seems illogical and unnecessarily complicated.

Despite some difficulty with interpretation (confounded by the regional grouping of the English data), these data provide a reasonable starting point for understanding how PCOS is currently commissioned across England and Wales. Three regions were using PDS contracts alone, five a mix of PDS and SLA, and twelve SLA alone. Table 4 summarises the numerous differences between the two contract types. The discrepancies in the levying of patient charges and payment of superannuation are the most controversial of these and this variation seems inequitable to both providers and patients alike.

As PCOS expands, there is likely to be greater demand from patients for a consistent and logical approach to the collection of patient charges, especially given the widespread expectation that specialist services (previously delivered in hospital settings) should be free at the point of delivery. This is the case with SLA contracts but not PDS, with some patients being charged for a procedure while others are not.

The data on sedation showed that inhalational sedation (IHS) with nitrous oxide was very rarely commissioned and the vast majority of sedation carried out is intravenous (IV) in nature. This is perhaps an oversight as IHS can often be used when IV sedation is contra-indicated. Furthermore, IHS has been shown to be effective in reducing anxiety in adults attending for oral surgery procedures8 making it a good alternative for those unsuitable for IV sedation on medical or social grounds.

Some commissioning bodies pay an additional fee for sedation and some do not. As there is clearly a cost to the provider in meeting the mandatory and best practice standards in sedation9,10 it would seem reasonable for this to be remunerated. It is possible that in some areas the additional cost has either been 'built in' to a generic fee or that the fee has been omitted to discourage over-prescription of sedation. Two out of three regions, which do not appear to pay an assessment fee, also commission sedation services. This is at odds with best sedation9 and medico-legal11 practice. Those regions that do not commission sedation in primary care may be paying more for their patients to be treated in secondary care where tariffs are often higher.2

Commissioners also need to consider any additional services that primary care oral surgeons may be able to provide, for example, soft tissue biopsies. This will mean organising for the specimen to be processed histopathologically as well as perhaps seeing the patient for a follow up appointment to check healing and to discuss the results. Similarly, specialist oral surgeons may be competent to see patients with temporomandibular joint pain or intra-oral white patches such as lichen planus. These conditions can require longer appointments to consult with and diagnose the patient with the potential need for multiple follow up appointments. Conditions such as these are not easily grouped into a basic oral surgery tariff and we would recommend an in-depth discussion with the provider to ensure a suitable tariff is agreed upon.

The broad nature of the request to include all PCOS means that the activity will reflect a wide skill mix ranging from dentists without formal training, but with an interest in oral surgery, to consultant-delivered care.12 As commissioning becomes more structured around the three tiers of care central to the commissioning model for dentistry,4 it is anticipated that managed clinical networks (MCNs) will take on a greater quality assurance role in matching treatment complexity to provider competence. What is of vital importance is that the provider should either be on the specialist list for oral surgery or be able to objectively demonstrate their competence. Any GDPs providing tier 2 oral surgery should be appropriately quality assured and all providers monitored to ensure they are delivering an optimal service.

The extent of the variation in tariff is surprising and the cost of providing a service illustrated in Table 3 makes it difficult to see how some of the minimum tariffs could be profitable while maintaining quality. The proposed introduction of patient reported outcome and experience measures4 (PROMS/PREMS) in England may go some way to providing real-time data on service quality.

Recommendations

In order to encourage the expansion of PCOS there should be an expectation that tariffs and contracts do not favour incumbent providers. New services require substantial investment in infrastructure and human resources to deliver complex treatment in a primary care environment. Contracts should reflect this, both in their duration and in the level of their remuneration. Robust management of contracts by commissioners is essential and can be facilitated through means such as MCN oversight of skill mix, PROMS/PREMS data and mandatory SAAD inspections9 for services offering sedation.

Any tariff has to be viable to allow potential providers to run their business. This may depend on the size of the practice as well as additional contracts in operation. Setting up a stand-alone practice is costly and any business plan will need to be approved for a business loan. In order for this to happen, the contract duration must be sufficient for the viability of a loan and for this reason the authors would recommend a minimum duration of five years for a contract. It may not be possible to offer a service for some of the lower tariffs unless other income streams in the practice provide sufficient long-term stability to make investment viable. This would be impossible for a stand-alone oral surgery provider. In addition, an annual uplift needs to be built in to the tariff to allow for inflation and the inevitable increasing costs of running a service over time.

A reasonable profit enables a practice to re-invest in equipment and infrastructure as well as to provide the appropriate staff training to ensure a gold standard oral surgery and sedation service. A narrow profit margin could result in corner cutting where patients will ultimately suffer if services fail or are of poor quality.

Table 5 shows the authors' recommended SLA tariff, which is based on a current SLA contract in Wales and is competitively priced based on the figures we obtained from our FOI request. The SLA fees should reflect the fact that there is no superannuation included (as with a PDS contract) and therefore should be higher to compensate for this.

We realise that the inclusion of a fee for patients who fail to attend is controversial but would advocate this providing the practice has taken all possible steps to ensure attendance. By this, we mean that it is not acceptable to merely send the patient an appointment letter in the post hoping that they will attend. We would suggest that once a patient is at the top of the waiting list they are sent a letter inviting them to contact the practice to make a mutually convenient appointment. Once the patient has telephoned and confirmed an acceptable time and date to attend, a confirmation letter with those details together with other relevant information is sent out via post or email. In addition to this, the patient should be sent a text message two days before the appointment. If after all of these measures, a patient still fails to attend their appointment we would argue that the practice has taken all possible steps to ensure the patient attends and as such the practice should not be financially disadvantaged if they do not. The 'fail to attend fee' does not provide any profit for the practice but, at least, goes some way towards covering the administration and surgery costs that have been incurred.

We would also recommend a higher consultation fee for patients with temporomandibular dysfunction. These patients have traditionally been seen in secondary care and can be more time consuming to see and treat. Some primary care specialists have the skills to manage a proportion of this group of patients12 and commissioners may want to take this into account, particularly if there are high waiting times for oral surgery out-patient appointments in secondary care in their region.

With regard to a PDS contract, the authors would recommend setting a minimum UDA value of £65. As there are units of orthodontic activity (UOAs)13 perhaps unit of surgical activity or 'USA' could be used rather than UDA. As per the PDS contract terms, one UDA (USA) would be awarded for a consultation alone, with three UDAs (USAs) being awarded per consultation and treatment episode. If IV sedation is provided, a fee equivalent to an additional three UDAs (USAs) should be paid (an additional service fee). In a deviation from the standard PDS contract, we would recommend more flexibility in treating patients with a higher clinical need. Our suggestion would be that for specific cases a second course of treatment could be claimed, allowing the oral surgeon the means to provide more than one treatment visit. We would anticipate that cases which may need a second treatment visit would be those where patients require extraction of more than six teeth, where patients need multiple extractions in three or four quadrants or where medically compromised patients need treatment to be staged. These proposals will involve ensuring consistent data gathering and robust data monitoring by commissioners and providers alike.

While there is a need for national consistency in commissioning, some local flexibility must be maintained. Although both contract types have advantages and disadvantages, their simultaneous use creates inequities to both providers and patients, therefore it would be preferable to move forward with a single contract model. Recommendations have been made by the BAOS for both PDS and SLA models. However, in terms of ease of use and of flexibility for the speciality of oral surgery, we feel that the use of an SLA system is more appropriate. The PDS system is restrictive in terms of structure of the contract as well as requiring a great deal more input in terms of administrative time. The SLA contract is more in line with secondary care contracts and, crucially, patients are not disadvantaged by being charged a fee for specialist oral surgery in primary care. If this type of contact could be tied in with superannuation it would be far more equitable for the providers and keep them in line with the rest of the NHS workforce.

Conclusion

Contracts in primary care oral surgery are extremely variable, in both their nature and remuneration. There is unquestionably scope for standardisation of tariffs and contracts both regionally and nationally. High priority should be given to procuring gold standard services provided by appropriately trained individuals, be they specialists or other quality assured and experienced oral surgeons outwith the specialist list. NHS England could and should address this promptly to ensure optimal patient care.

References

Medical Education England. Review of Oral Surgery Services and Training. 2010.

Kendall N . Improving access to oral surgery services in primary care. Prim Dent Care 2009; 16: 137–142.

Dyer T A . A five-year evaluation of an NHS dental practice-based specialist minor oral surgery service. Community Dent Health 2013; 30: 219–226.

NHS England. Guide for Commissioning Oral Surgery and Oral Medicine. 2015. Available at http://www.england.nhs.uk/commissioning/wp-content/uploads/sites/12/2015/09/guid-comms-oral.pdf (accessed May 2017).

Legislation.gov. Freedom of Information Act 2000. 2000. Available at http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2000/36 (accessed May 2017).

NHS. NHS Commissioning Boards: Local area teams. NHS England, 2012. Available at https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2012/06/lat-senates-pack.pdf (accessed May 2017).

NHS Wales. Public Health Wales Observatory interactive map. 2016. Available at http://www.publichealthwalesobservatory.wales.nhs.uk/information-about-the-interactive-map (accessed May 2017).

Hierons R J, Dorman M L, Wilson K, Averley P, Girdler N . Investigation of inhalational conscious sedation as a tool for reducing anxiety in adults undergoing exodontia. Br Dent J 2012; 213: E9.

Society for the Advancement of Anaesthesia in Dentistry. Guidance for Commissioning NHS England Dental Conscious Sedation Services. London, 2013. Available at http://s540821202.websitehome.co.uk/Wordpress2/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/SAAD-Guidance-Commissioning-Sedation.pdf (accessed May 2017).

Intercollegiate Advisory Committee for Sedation in Dentistry. Standards for Conscious Sedation in the Provision of Dental Care. London, 2015. Available at http://www.dstg.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/Linked-IACSD-2015.pdf (accessed May 2017).

DDU. Dental professionals should give patients a 'cooling off period'. DDU, 2012. Available at https://www.theddu.com/press-centre/press-releases/dental-professionals-should-give-patients-a-cooling-off-period (accessed May 2017).

Brotherton P, Gerrard G, Bennett K, Coulthard P . The scope of practice of UK oral surgeons. Oral Surg 2015; 8: 83–90.

NHS England. Transitional commissioning of primary care orthodontic services. NHS England, 2013. Available at https://www.england.nhs.uk/commissioning/wp-content/uploads/sites/12/2015/09/orth-som-nov.pdf (accessed May 2017).

UK Parliament. NHS (Dental Charges) (Amendment) Regulations 2016: Written statement – HCWS606. UK Parliament, 2016. Available at http://www.parliament.uk/business/publications/written-questions-answers-statements/written-statement/Commons/2016-03-11/HCWS606/ (accessed May 2017).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr Paul Averley for his help and advice during the preparation of this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed Paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hierons, R., Gerrard, G. & Jones, R. An investigation into the variability of primary care oral surgery contracts and tariffs in England and Wales (2014/2015). Br Dent J 222, 870–877 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2017.500

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2017.500

This article is cited by

-

Erratum

British Dental Journal (2017)