Key Points

-

Notes that Peutz-Jeghers syndrome is an inherited disorder characterised by gastrointestinal polyposis.

-

Highlights that Peutz-Jeghers patients have an increased risk for developing cancer, both in the gastroinstestinal tract as well as in other organs.

-

Suggests dentists should be aware of Peutz-Jeghers syndrome when characteristic mucocutaneous pigmentations are observed.

Abstract

Peutz-Jeghers syndrome (PJS) is a rare, autosomal dominant inherited disorder, caused by germline mutations in the LKB1 tumour suppressor gene. It is clinically characterised by distinct perioral mucocutaneous pigmentations, gastrointestinal polyposis and an increased cancer risk in adult life. Hamartomatous polyps can develop already in the first decade of life and may cause various complications, including abdominal pain, bleeding, anaemia, and acute intestinal obstruction. Furthermore, patients have an increased risk for developing cancer, both in the gastrointestinal tract as in other organs. The medical management of PJS mainly consists of surveillance and treatment of the hamartomatous polyps. Upper and lower endoscopies are recommended for surveillance and removal of PJS polyps in the stomach and the small and large intestine. Furthermore, the high risk for pancreatic cancer justifies surveillance of the pancreatic region by MRI or endoscopic ultrasound. In addition, breast and gynaecological surveillance is recommended for female patients. Although the genetic defect underlying PJS is known, the pathogenesis of hamartomas and carcinomas is unclear. More insight into the molecular background of PJS might lead to targeted therapies for patients with this syndrome.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In 1896, the London physician Sir Jonathan Hutchinson illustrated a case of twin sisters with 'black pigmented spots on the lips, and inside of the mouth' (Fig. 1).1 These pigmentations were different from the typical brown freckles located on the wings of the nose and cheeks. This was the first notification of the typical skin findings of Peutz-Jeghers syndrome (PJS). A follow-up of the so-called 'Hutchinson twins' noted that one sister died of intestinal blockage at the age of 20 years, and the second twin died of breast cancer at age 52.2,3

In 1921, the Dutch physician Jan Peutz described the combination of mucocutaneous pigmentations and gastrointestinal polyps in three young siblings.4 More than 20 years later, the American physician Harold Jeghers described two patients with the same symptoms.3 These observations led to the description of the syndrome in 1949 by Jeghers, McKusick and Katz in the New England Journal of Medicine. Finally, in 1954 the eponym Peutz-Jeghers syndrome was introduced by Bruwer and colleagues.5

Today, the clinical diagnosis of PJS is defined by diagnostic criteria of the World Health Organisation (WHO) (Box 1).6 The syndrome is rare, with an incidence estimated between 1 in 50,000 to 1 in 200,000 live births.7

Genetic background

PJS is caused by a germline mutation in the liver kinase B1 (LKB1, also known as serine/threonine kinase 11; STK11) tumour suppressor gene, located on chromosome 19p13.3 of the human genome.8,9 The syndrome inherits in an autosomal dominant way, and in approximately 25% of cases a de novo mutation is present. With the currently available techniques, a germline mutation is found in 80–94% of clinically affected patients, of which more than 60% is a point mutation.10,11,12 The clinical features of PJS vary among patients and affected families. Despite several studies, no convincing genotype-phenotype correlation has been demonstrated.13,14,15

Clinical features

Mucocutaneous pigmentations are seen in around 95% of PJS patients, and can be the first clinical sign before any gastrointestinal symptoms occur. The mucocutaneous lesions are flat, have a blue-greyish colour, and vary in size between 1 to 5 mm. They are mostly seen in the perioral region, but can also be found on the buccal mucosa, around the nostrils, at the hands and feet, and in the peri-anal region. Pigmentations on the lips are distinctive since they cross the vermilion border and are often much darker and more densely clustered than common freckles (Fig. 2). Their origin remains poorly understood. It is hypothesised that they are benign neoplasms of melanocytes with limited growth potential.16 The pigmentations develop in infancy and can be the first clinical sign before any gastrointestinal symptoms occur. They fade during adolescence in most patients, but less so on the buccal mucosa. Although the pigmentations are not believed to have malignant potential, the cosmetic effect can be burdensome.

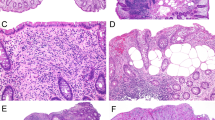

The predominant clinical feature of PJS is polyposis of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. In rare cases, polyps are found outside the gastro-intestinal tract, for example in the gall bladder, the lungs, the urogenital tract or nasopharynx. Peutz-Jeghers polyps have a typical macroscopic and microscopic appearance, and are referred to as hamartomas. They are often pedunculated and consist of a branched, tree-like smooth muscle core covered with normal epithelium (Fig. 3).17 Hamartomas are found throughout the GI tract, but are mainly located in the small intestine, usually in the jejunum.18,19 They can develop in the first decade of life and may cause complaints of abdominal pain, blood loss, or acute intestinal obstruction, in particular resulting from intussusception of a small bowel segment carrying a large hamartoma (≥15 mm).19 The latter often requires acute surgical intervention. By the age of ten, one third of patients experience polyp-related symptoms.20 The cumulative risk of intussusception by the age of 20 years is 50%.19

During the second half of the 20th century, epidemiological and molecular genetic studies revealed that PJS is also associated with an increased cancer risk. A lifetime risk for any cancer between 37% and 93%, and relative risks ranging from 10 to 18 in comparison with the general population have been reported.21 A substantial part of this elevated cancer risk is attributed to an increased risk for gastrointestinal tumours (mainly colorectal, small bowel, gastric and pancreatic cancer). A cohort study of 133 Dutch PJS patients showed a cumulative cancer risk of 76% at age 70 years, with a gastrointestinal cancer risk of 51% at this age (Fig. 4).22 Female patients are at even higher risk than male patients, because of the additional risk of breast cancer and gynaecological cancers in women.

Predominantly due to the elevated cancer risk, mortality in PJS patients is significantly increased compared to the general population. In the study of van Lier et al.22 42 of the 133 patients had died at a median age of 45 years, including 28 cancer related deaths (67%).

In addition to malignant gynaecological tumours, female PJS patients of reproductive age can also develop small, asymptomatic, bilateral ovarian tumours, known as 'sex-cord' tumours with annular tubules (SCTATs) at a young age.23 PJS-associated SCTATs have a low malignant potential and a good prognosis. These tumours are often associated with signs of hyperestrogenism, causing precocious puberty. Male PJS patients have an increased incidence of Sertoli cell testicular tumours.24,25 These lesions are often hormonally active and patients can present with testicular enlargement or gynaecomastia.

At present, the pathogenesis and molecular mechanisms underlying PJS-associated cancer development are unclear. Although a hamartoma-carcinoma sequence, in which the hamartomas are considered premalignant lesions, has been proposed by some,26,27,28 several facts contradict this theory. Dysplastic and carcinomatous changes do occur in hamartomas, but are very rare.26,29,30 In addition, the location of the gastrointestinal malignancies in PJS patients does not always correlate with the location of the hamartomatous polyps.29,31 Furthermore, the number of polyps decreases with advancing age, whereas the cancer incidence increases.18,32 Moreover, a much higher cancer incidence would be expected if hamartomas were indeed precursor lesions, given the high polyp load in most PJS patients. This all suggests that hamartomas and carcinomas are two distinct entities of PJS.

Surveillance and treatment

Because of the risk of hamartoma-related complications and the increased cancer risk in PJS, and due to the lack of effective methods for chemoprophylaxis to prevent the formation of hamartomas and malignancies, patient management should focus on prevention by surveillance. Over the years, several surveillance recommendations have been proposed.7,21,33,34,35 However, all these recommendations are based on clinical experience and expert opinion. No evidence-based surveillance strategy for PJS is available since no controlled trials on the effectiveness of such programmes have been published.

It is generally accepted that surveillance of the gastrointestinal tract should start at a young age (8–10 years). Upper and lower endoscopies are recommended for detection and removal of PJS polyps in the stomach and the small and large intestine. A diameter ≥15 mm is regarded an indication for polypectomy. At later age, surveillance of the gastrointestinal tract should also address detection of precursor lesions or malignancies at an early, asymptomatic stage. Furthermore, female PJS patients should undergo regular surveillance of the breasts and genital tract from the age of 25–30 years. Since data show that PJS patients also harbour a highly increased risk for pancreatico-biliary cancer, surveillance of the pancreas by yearly endoscopic ultrasound and/or MRI from the age of 30 years seems feasible.36 Currently, this is only done in well-defined research protocols.

Psychological burden

PJS is a chronic disease that affects patients from a young age and is associated with considerable morbidity and decreased life expectancy. Furthermore, regular and multiple invasive surveillance examinations are needed. This affects the psychological condition and quality of life of patients. Compared to the general population, PJS patients suffer more frequently from mild depression and experience a poorer mental quality of life.37,38 Furthermore, they encounter more limitations in daily functioning due to emotional problems, and experience a poorer general health perception. Both physical and psychological burden of disease also influence the decisions of PJS patients regarding family planning and the use of prenatal genetic testing, especially in women.39 Besides the physical care, accurate genetic counselling and psychological support should therefore be part of the care for PJS patients.

Considering the increased risk of developing cancer, early diagnosis of PJS is essential. Dentists and other oral healthcare professionals might play a valuable role in the diagnosis and referral of patients by recognising the typical pigmentations.

References

Hutchinson J . Pigmentation of lips and mouth. Vol VII, Archives of Surgery London: West, Newman, 1896.

Weber F . Patches of deep pigmentation of oral mucous membrane not connected with Addison's disease. Q J Med 1949; 12: 404–408.

Jeghers H, Mc K V, Katz K H . Generalized intestinal polyposis and melanin spots of the oral mucosa, lips and digits; a syndrome of diagnostic significance. N Engl J Med 1949; 241: 1031–1036.

Peutz J L A . Over een zeer merkwaardige, gecombineerde familiaire polyposis van de slijmvliezen van den tractus intestinalis met die van de neuskeelholte en gepaard met eigenaardige pigmentaties van huid en slijmvliezen. Ned Maandschr v Geneesk 1921; 10: 134–146.

Bruwer A, Bargen J A, Kierland R R . Surface pigmentation and generalized intestinal polyposis (Peutz-Jeghers syndrome). Proc Staff Meet Mayo Clin 1954; 29: 168–171.

Hamilton S R, Aaltonen L A . World Health Organization Classification of Tumours. Pathology and Genetics. Tumours of the Digestive System. Lyon: IARC Press 2001.

Giardiello F M, Trimbath J D . Peutz-Jeghers syndrome and management recommendations. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2006; 4: 408–415.

Haemminki A, Markie D, Tomlinson I et al. A serine/threonine kinase gene defective in Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. Nature 1998; 391: 184–187.

Jenne D E, Reimann H, Nezu J et al. Peutz-Jeghers syndrome is caused by mutations in a novel serine threonine kinase. Nat Genet 1998; 18: 38–43.

Aretz S, Stienen D, Uhlhaas S et al. High proportion of large genomic STK11 deletions in Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. Hum Mutat 2005; 26: 513–519.

Volikos E, Robinson J, Aittomaki K et al. LKB1 exonic and whole gene deletions are a common cause of Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. J Med Genet 2006; 43: e18.

de Leng W W, Jansen M, Carvalho R et al. Genetic defects underlying Peutz-Jeghers syndrome (PJS) and exclusion of the polarity-associated MARK/Par1 gene family as potential PJS candidates. Clin Genet 2007; 72: 568–573.

Amos C I, Keitheri-Cheteri M B, Sabripour M et al. Genotype-phenotype correlations in Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. J Med Genet 2004; 41: 327–333.

Lim W, Olschwang S, Keller J J et al. Relative frequency and morphology of cancers in STK11 mutation carriers. Gastroenterology 2004; 126: 1788–1794.

Schumacher V, Vogel T, Leube B et al. STK11 genotyping and cancer risk in Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. J Med Genet 2005; 42: 428–435.

Rowan A, Bataille V, MacKie R et al. Somatic mutations in the Peutz-Jeghers (LKB1/STK11) gene in sporadic malignant melanomas. J Invest Dermatol 1999; 112: 509–511.

WHO Classification of Tumours of the Digestive System, 4 ed. Vol 3. Lyon: IARC Press 2010.

Utsunomiya J, Gocho H, Miyanaga T et al. Peutz-Jeghers syndrome: its natural course and management. Johns Hopkins Med J 1975; 136: 71–82.

van Lier M G, Mathus-Vliegen E M, Wagner A et al. High cumulative risk of intussusception in patients with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome: time to update surveillance guidelines? Am J Gastroenterol 2011; 106: 940–945.

Tovar J A, Eizaguirre I, Albert A et al. Peutz-Jeghers syndrome in children: report of two cases and review of the literature. J Paediatr Surg 1983; 18: 1–6.

van Lier M G, Wagner A, Mathus-Vliegen E M et al. High Cancer Risk in Peutz-Jeghers Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Surveillance Recommendations. Am J Gastroenterol 2010; 105: 7.

van Lier M G, Westerman A M, Wagner A et al. High cancer risk and increased mortality in patients with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. Gut 2011; 60: 141–147.

Young R H, Welch W R, Dickersin G R et al. Ovarian sex cord tumour with annular tubules: review of 74 cases including 27 with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome and four with adenoma malignum of the cervix. Cancer 1982; 50: 1384–1402.

Wilson D M, Pitts W C, Hintz R L et al. Testicular tumours with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. Cancer 1986; 57: 2238–2240.

Young S, Gooneratne S, Straus F H et al. Feminizing Sertoli cell tumours in boys with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. Am J Surg Pathol 1995; 19: 50–58.

Hizawa K, Iida M, Matsumoto T et al. Neoplastic transformation arising in Peutz-Jeghers polyposis. Dis Colon Rectum 1993; 36: 953–957.

Perzin K H, Bridge M F . Adenomatous and carcinomatous changes in hamartomatous polyps of the small intestine (Peutz-Jeghers syndrome): report of a case and review of the literature. Cancer 1982; 49: 971–983.

Gruber S B, Entius M M, Petersen G M et al. Pathogenesis of adenocarcinoma in Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. Cancer Res 1998; 58: 5, 267–270.

Korsse S E, Biermann K, Offerhaus G J et al. Identification of molecular alterations in gastrointestinal carcinomas and dysplastic hamartomas in Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. Carcinogenesis 2013; 34: 1611–1619.

Latchford A R, Neale K, Phillips R K et al. Peutz-jeghers syndrome: intriguing suggestion of gastrointestinal cancer prevention from surveillance. Dis Colon Rectum 2011; 54: 1547–1551.

Dozois R R, Judd E S, Dahlin D C et al. The Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. Is there a predisposition to the development of intestinal malignancy? Arch Surg 1969; 98: 509–517.

Giardiello F M, Brensinger J D, Tersmette A C et al. Very high risk of cancer in familial Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. Gastroenterology 2000; 119: 1447–1453.

Tomlinson I P, Houlston R S . Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. J Med Genet 1997; 34: 1007–1011.

Lindor N M, Greene M H . The concise handbook of family cancer syndromes. Mayo Familial Cancer Program. J Natl Cancer Inst 1998; 90: 1039–1071.

Beggs A D, Latchford A R, Vasen H F et al. Peutz-Jeghers syndrome: a systematic review and recommendations for management. Gut 2010; 59: 975–986.

Korsse S E, Harinck F, van Lier M G et al. Pancreatic cancer risk in Peutz-Jeghers syndrome patients: a large cohort study and implications for surveillance. J Med Genet 2013; 50: 59–64.

Woo A, Sadana A, Mauger D T et al. Psychosocial impact of Peutz-Jeghers Syndrome. Fam Cancer 2009; 8: 59–65.

van Lier M G, Mathus-Vliegen EM, van Leerdam M E et al. Quality of life and psychological distress in patients with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. Clin Genet 2010; 78: 219–226.

Van Lier M G, Korsse S E, Mathus-Vliegen E M et al. Peutz-Jeghers syndrome and family planning: the attitude towards prenatal diagnosis and pre-implantation genetic diagnosis. Eur J Hum Genet 2012; 20: 236–239.

McGarrity T J, Kulin H E, Zaino R J . Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol 2000; 95: 596–604.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed Paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Korsse, S., van Leerdam, M. & Dekker, E. Gastrointestinal diseases and their oro-dental manifestations: Part 4: Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. Br Dent J 222, 214–217 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2017.127

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2017.127

This article is cited by

-

Ultrasonography with the colonic segment-approach for colonic polyps in children

Pediatric Radiology (2019)

-

Hereditary Polyposis Syndromes

Current Treatment Options in Gastroenterology (2019)