Key Points

-

Reports the oral health education and preventive treatment needs that should be incorporated into conscious sedation care pathways.

-

Provides a unique insight into the challenges parents face in adopting and maintaining healthy behaviours and into their specific needs for oral health education and promotion.

-

Informs readers about the past experiences of oral health preventive services and the support that families of anxious children would like to help to inform efficient planning of future health services.

Abstract

Introduction Few studies have assessed the preventive needs of children treated under conscious sedation or their parents'/guardians' views regarding oral health education.

Aim To report on the profile of children who required treatment under conscious sedation. Also to obtain the views of the parents or guardians of these children on their experiences of oral health preventive services and the support they would like in order to improve their child's oral health.

Method A researcher-administered questionnaire was used to collect quantitative and qualitative responses from a consecutive sample of 123 parents/guardians during their child's sedation appointment at King's College Hospital.

Results Caries was the main reason for the child's sedation treatment and 77.2% of them were high caries risk. Parents reported that their general dentist had given advice about sugar (80%) and tooth-brushing (74%), but few had prescribed fluoride varnish (15%), fissure sealants (12%) or a fluoride rinse (36%). Parents felt challenged by the ready availability of sugar, and others suggested difficulty in maintaining healthy oral habits in complex families. Overall, the majority of parents thought leaflets, health professionals' advice, and Internet websites could be informative, and they requested school- and hospital-based prevention programmes.

Discussion The majority of children had high caries risk. They had received advice but not professional preventive treatment such as fluoride varnish and fissure sealants. Their parents requested preventive education using new technologies and media and better access through school-based and hospital prevention programmes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Dental anxiety is the most common reason for referral to specialist paediatric dentistry services.1,2 The Paediatric Dentistry Department at King's College Hospital (KCH) performs at least 1,283 treatment sessions under conscious sedation (including nitrous oxide inhalation sedation, oral midazolam sedation, and intravenous midazolam sedation – discounting episodes delivered by trainees and undergraduates) every year, with the majority being for the treatment of dental caries. However, there appears to be an unmet need for preventive care. In fact, there have been no previous studies to look into either the preventive needs or the experience of oral health preventive services of this cohort of families. Neither the recently published guidelines for conscious sedation nor the previous NICE guidelines mentioned disease prevention.3,4

It makes sense that any sedation care pathway that provides care for high caries risk children should include preventive education and support behaviour change.5 Although life-style changes to improve diet and oral hygiene habits can be difficult to achieve, oral health education is a key component part of disease prevention. Indeed, the Ottawa Charter for oral health promotion stressed the importance of helping individuals improve personal oral health habits, achieved through the provision of information, health education and enhancement of life skills.6

An evidence based toolkit by the Department of Health and BASCD (2014) provides a template of caries preventative interventions aimed at the population as a whole, and at those patients who are of a high caries risk, in particular.7 Evidence also suggests that a dental system that focuses on preventive rather than curative treatment could lead to significant economic savings.8 Moreover, health professionals have an ethical responsibility to inform their patients about how to prevent disease.9 In that sense, everyone in the care pathway, from GDPs to community and hospital specialist services have a significant role to play in the management of young children with caries. Previous studies, from this unit have reported the preventive knowledge and needs of children referred for general anaesthesia.10,11 One of these studies has suggested that GDPs in England feel frustrated and isolated, and are facing barriers that are related to the child, parents, social and cultural environment, level of training, guideline implementation, secondary care communication, health policy and funding.5

The aim of this study is to report on the profile of children who required treatment under conscious sedation and obtain the views of their parents or guardians on their experiences of oral health preventive services and the support they would like to have to in order to improve their child's oral health. The authors will use the term parent to cover both parents and legal guardians throughout.

Material and methods

This study received approval from KCH audit committee and was registered under CASS (Clinical Audit Support System) number CG112. The two researchers (DA and MSO) interviewed a consecutive sample of 123 children, and their parents, who had already been scheduled to receive dental treatment under conscious sedation at King's College Hospital. This setting is one of the largest sedation service providers in the UK, and services a catchment area that includes South East London and covers part of the neighbouring counties of Kent, Surrey and Sussex.

The interview questionnaire was previously published by Olley et al.10 and included 23 closed and open questions and was administered as a one-to-one interview between the parent and one of the researchers (Appendix 1). The interviews took place between May 2011 and January 2013 during their child's already scheduled, sedation visit. Recorded data included: patient's details; family's demographics; status of the referring practitioner; ASA grade of the patient; dental diagnosis; caries risk assessment; type of treatment required under sedation; type of sedation; and previous history of general anaesthesia or conscious sedation for dental treatment. Questionnaires were made anonymous using the hospital identification number. Those parents who declined to take part, those who did not speak English and those whose child had an aborted conscious sedation session were excluded. If the caries risk assessment was not already recorded clearly in the case-notes, an assessment was carried out by the researcher based on the clinical notes according to the Faculty of General Dental Practitioners (FGDP) for the selection criteria for dental radiography.12

Quantitative data was extracted from the closed questions. This was then entered into SPSS (SPSS for Windows, Version 20) and analysed. The responses to the open-ended questions, as well as any additional comments from the parents, was recorded verbatim in writing by the researcher and later categorised by theme. These were entered into a Microsoft Office Excel spread-sheet and analyszed using thematic data analysis.13 This is a common approach to qualitative data analysis which requires examining the data to identify relevant themes through a series of systematic steps. The researchers (DA and MSO) used the same approach as Aljafari et al., by first familiarising themselves with the data through reading the transcripts, followed by a more detailed reading to assign primary codes to the data. As more data were collected, these primary codes were being constantly reviewed and modified, combined or truncated to create appropriate themes. During data analysis, the researchers would regularly meet with the third researcher (MTH) to read through transcripts and discuss coding and emerging themes to encourage the reliability.

Results

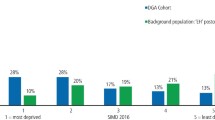

A total of 123 interviews were conducted with the parents/guardians of children treated under conscious sedation. Details of the sample of children are shown in Table 1. The majority of patients (78%) were referred by their GDP. The source of referral was the specialist hospital-based paediatric dental accident and emergency service (6%), the family doctor (4%), and another hospital dental professional (5%). Another 5% were referred from other sources. The source of referral was not recorded for two patients. Sixty children were treated under inhalation sedation, 37 under oral sedation, and 26 under intravenous sedation. The mean age of patients undergoing treatment under all three types of sedation was eight and a half years and the age range was from two to 16 years. There was no statistically significant difference in the gender of patients in different sedation groups. Most children were either white (40%) or black British (35%). The remainders were Asian, mixed or other. The ethnic group of one patient in the sample was not reported. Around 94% of children in the total sample have always lived in the UK and around 6% have previously lived in another country. A large proportion of parents had professional (managerial/technical/skilled/non-manual) occupations (47%) and the remainders either had manual occupations (27%) or were unemployed (26%). The reporter was the mother in 71.5% of the interviews, the father in 25%, and both in three of them. A step mother was interviewed in one case as she was the accompanying adult.

Seventy-one per cent of the children had been referred for caries management, 19% were referred due to trauma, and the remaining 10% were referred for other reasons, such as orthodontic extractions, extractions of supernumerary or submerged teeth, or due to anomalies such as molar incisor hypomineralisation, or the need for minor oral surgery, for example, excisional biopsy. The reason for using sedation was anxiety in 50% of the cases and pre-cooperative behaviour in 21% of the cases. In 29% of cases, the use of sedation was attributed to the need for complex or extensive treatment.

Fifteen percent of the children had had a previous general anaesthetic (GA) for dental reasons and so had 22% of their siblings. Half of the children who had a previous dental GA also had a previous experience of conscious sedation. Another 6.5% of those in the total sample had past experience of dental conscious sedation only.

Regarding the impact of the child's poor oral health on the child and on the family, parents reported that 65% of the children suffered from pain, 31% suffered from difficulty chewing or talking, and 25% from emotional problems (such as being irritable or miserable). Around 9% of the parents also reported some impact on their child's self-confidence, 5% reported some impact on activities (such as singing or playing a musical instrument), 5% reported some social functional impact (such as playing or speaking to friends), and 4% reported some impact on their child's general health. These data are summarised in Figure 1.

Eighty percent of the parents reported that their GDP had advised them about sugar consumption, a further 76.4%, reported having received advice about tooth-brushing and 45.5% had been advised to use fluoride toothpaste. Fifteen percent said their GDP talked to them about fluoride varnish and 12% about fissure sealants, and 10.5% said their GDP talked about sugar-free chewing gum. Only 15% of parents of children aged three years and above said they were advised about fluoride varnish. Fifteen per cent of the parents of 'at high caries risk' children aged six years and above (thus likely to have erupted permanent first molars) said they were advised about fissure sealants by their GDP and only 36% of parents of 'at high caries risk children' aged eight years and above said they were advised regarding the daily use of fluoride mouthwash.

Regarding the parents views on oral health education delivery, the qualitative data showed that the parents faced challenges in promoting their children's oral health. This resulted in the identification of seven main themes, namely: availability of sugars (Theme 1); lack of oral health awareness (Theme 2); parenting skills (Theme 3); shifting responsibilities (Theme 4); challenging behaviour of adolescents (Theme 5); grandparents' adverse influence (Theme 6); and difficulty with brushing their children's teeth (Theme 7). It appeared from the qualitative data that the obstacles faced by parents in maintaining their children's oral-health were quite similar.

Availability of sugars was certainly one of the most important themes. A parent summarised this as follows, 'I think there is a shift within society towards more and more sugary foods sugar is there everywhere' (Interview No: 16, Theme 1; 7-year-old high caries risk child). Lack of oral health awareness was a main theme as well. One parent said, 'I wasn't informed of all of this before I knew all about it after my kids' teeth got rotten' (Interview No: 62, Theme 2; 14-year-old high caries risk child). Parents also acknowledged all the parenting challenges they faced with their children. One parent admitted 'I can't say “No” when they ask for sweets' (Interview No: 103, Theme 3; 6-year-old high caries risk child). Another said, commenting on the challenging behaviours of adolescents, 'I actually have a problem with her. She is in this age when she does not listen to me, and her attitude even at school is really difficult' (Interview No: 114, Theme 5; 16-year-old high caries risk child).Other parents, however, seemed to be shifting the responsibility to others. One father said 'Me and his mother are separated. He went with his mom to Columbia for three months. His grandparents and everyone there was giving him sweets, too much sweets [sic] and now his teeth are rotten' (Interview No: 116, Theme 4; 6-year-old high caries risk child).

Regarding the parents' views on oral health education delivery, the quantitative data showed that the majority of parents (83%) reported that they thought that leaflets are useful in providing oral health education. Almost 80% of them thought that health professionals were the best able to provide this information. Seventy percent thought that internet websites could be helpful, 39% thought that DVDs might be helpful and only 32% thought they would benefit from a telephone helpline service (Fig. 2).

Interestingly, the majority of parents (78%) reported that they would like to have access to more tooth brushing programmes in schools and nurseries in their area. Also, 68% percent of them thought that an oral health programme in the hospital would be helpful. Half of the parents thought training one of their peers from their local community to give oral health advice would be helpful, and 30% thought home visits from dental professionals would be helpful. Only 11% said they would like help finding another dentist. Only one parent said we should do nothing (Fig. 3).

Discussion

The majority of children requiring treatment under conscious sedation had caries, which implies that a high proportion were in need of preventive intervention. Failure of current caries prevention programmes were highlighted by the frequency of previous dental GA treatment that was reported by the parents, not only for the children in this sample but also for almost a fifth of their siblings.10,14,15,16 This is perhaps a consequence of poor engagement with dental health professionals and inadequate tailored preventive support following their previous GA or conscious sedation treatment episodes, rather than efforts by the general dental practitioners to provide verbal advice regarding sugar consumption and tooth brushing. These previous contacts are 'teachable moments' and should be regarded as valuable opportunities to target these families to provide preventive education and behaviour change management. The lack of provision of fluoride varnish and fissure seals, or advice regarding fluoride rinses may be due to failed post-operative follow-up attendance. We already know that many families with children with early childhood caries tend to attend their dentist on an emergency only basis, so perhaps the GDPs just did not have the opportunity to provide this care. The statistics from NHS Digital recently showed that more than 40% of children in England did not see a dentist last year.17 On the other hand, parents of children in this study, who received advice from their dentist described it as general knowledge, which was mainly based on tooth brushing and restricting sugar in the diet. Only a few received fluoride varnish application and fissure sealants. Clearly, more education needs to be directed not only towards those families, but also the general dental practitioners to ensure that the GDPs follow and implement the Department of Health guidelines on prevention of dental caries. In that sense, including prevention in the mandatory CPD scheme for dental professionals might be the best way forward.

Nutbeam18 recommended that oral health promotion interventions should include: health promotion action (for example, education), have validated health promotion outcomes (for example, health behaviour), and include objective health and social outcomes (for example, caries activity, plaque score and BPE). Parents of children with high caries risk usually display lack of knowledge on the prevention of dental caries. Amin and Harrison19 found that the GA experience led parents to adopt healthy behaviours soon after the GA but had no effect on their long-term preventive behaviours.19

Interventions in behaviour change are likely to be reproducible if they are reported clearly. In order to identify the type or types of intervention that are likely to be effective, it is important to analyse the full range of options available and use a rational system for selecting from among them.20,21 A 'care pathway' for high caries risk children who need treatment under conscious sedation must include prevention advice and support to implement behavioural change at home as an integral part of the specialist management. Such a prevention-based approach is not only associated with less morbidity, but also ensures that these children will become low caries risk young adults.

The parents in the present study appear to prefer leaflets as a source of oral health education.22,23 Evidence, however, suggests that for leaflets to be effective they have to have a simple and straightforward message, and use pictorial aids.24 Personal contact with health professionals was also seen by parents to be a valued source of preventive information.10,25,26 Families are interested in the internet as a potential source of oral health information.27,28 Interestingly, internet websites were thought to be a useful source of preventive information by 70% of parents in the present study and by 64% of those in the study by Olley et al.10 However, there is evidence that the internet can be a source of unreliable information29 and thus any websites aiming at dental health education have to be accurate, monitored and continuously updated. In the present study, new media sources such as DVDs and video-games were welcomed by 40% of the parents, which highlights that children nowadays can be targeted with means that were not available before.

It appeared from the qualitative data that the obstacles faced by parents in maintaining their children's oral-health were comparative to those reported in other studies.10,19 The themes and comments made by parents highlighted the genuine challenges they faced in promoting their children's oral health which actually require adoption of life-style changes within the whole family. This might not be easily achieved with the everyday stresses that these families face; over half of them were unemployed or from low-income manual backgrounds, and the average number of siblings per family was 2.66.

Accordingly, rather than adopting a blaming approach, health professionals have a responsibility to provide these parents with continuous one-to-one support and encouragement to adopt life-style changes. The family-centred empathetic approach favoured by many parents in the present study has to be acknowledged. There seems to be an imperative to target these families more, improve the skills of health professionals in oral-health counselling and concentrate the efforts of all healthcare professionals that are in contact with them, not just dentists.

Therefore, treating oral disease in children under conscious sedation should by no means be a one-off event. Treatment under conscious sedation is difficult, expensive and associated with higher morbidity. Oral diseases are the fourth most expensive diseases to treat in industrialised countries and evidence has shown significant savings in dental expenditures in industrialised countries that have adopted a preventive approach.7 Thus, the importance of targeting these groups with continuous tailored prevention cannot be overemphasised.

This study proposes that a care of pathway for high caries risk children who need treatment under conscious sedation should include personalised education and support for behaviour change to improve oral and general health habits (Fig. 4). Further studies will be required to test the effectiveness of this, and the efficacy of new technology to deliver better oral health education for this group of children and their families.

Conclusion

The majority of children treated under conscious sedation in the Paediatric Dentistry Department at KCH were 'high caries risk' and at least a fifth of the families had had previous contact with specialist dental services for either sedation or general anaesthesia. The oral health preventive support received by the families did not match DOH toolkit guidance in respect to fluoride varnish, fissure sealants or fluoride mouthwash. Their parents/guardians felt challenged by the ready availability of sugar and some found parenting a challenge. They requested school and hospital-based preventive programmes, personal delivery from an oral healthcare professional and leaflet and web-based educational information.

References

Evans D, Attwood D, Blinkhorn A S, Reid J S . A review of referral patterns to paediatric dental consultant clinics. Community Dent Health 1991; 8: 357–360.

Shaw A J, Nunn J H, Welbury R R . A survey of referral patterns to a paediatric dentistry unit over a 2-year period. Int J Paediatric Dent 1994; 4: 233–237.

Royal College of Surgeons. Standards for conscious sedation in the provision of dental care. Report of the Intercollegiate Advisory Committee for Sedation in Dentistry. 2015 https://www.rcseng.ac.uk/dental-faculties/fds/publications-guidelines/standards-for-conscious-sedation-in-the-provision-of-dental-care/

National Institute for Clinical Excellence. Clinical guideline 112. Sedation in children and young people. Sedation for diagnostic and therapeutic procedures in children and young people. 2010. Available online at https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/CG112 (accessed November 2016).

Aljafari A K, Gallagher J E, Hosey M T . Failure on all fronts: General dental practitioners' views on promoting oral health in high caries risk children – a qualitative study. BMC Oral Health 2015; 15: 45.

World Health Organization. Ottawa charter for health promotion: An International Conference on Health Promotion, the move towards a new public health. 1986. Available online at http://www.who.int/healthpromotion/conferences/previous/ottawa/en/ (accessed November 2016).

Public Health England. Delivering better oral health: An evidence-based toolkit for prevention. Third edition. 2014. Available online at https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/367563/DBOHv32014OCTMainDocument_3.pdf (accessed November 2016).

Peterson P E, Bourgeois D, Ogawa H, Estupinan-Day S, Ndiaye C . The global burden of oral diseases and risks to oral health. Bull World Health Organ 2005; 83: 661–669.

Kay E J, Locker D . Is dental health education effective? A systematic review of current evidence. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 1996; 24: 231–235.

Olley R C, Hosey M T, Renton T, Gallagher J . Why are children still having preventable extractions under general anaesthetic? A service evaluation of the views of parents of a high caries risk group of children. Br Dent J 2011; 210: 1–8.

Aljafari A K, Scambler S, Gallagher J E, Hoset M T . Parental views on delivering preventive advice to children referred for treatment of dental caries under general anaesthesia: A qualitative investigation. Community Dent Health 2014; 31: 75–79.

FGDP. Selection Criteria for Dental Radiography, 2nd edition. Faculty of General Dental Practitioners (UK), 2004.

Ritchie J, Lewis J . Qualitative research in practice: A guide for social science students and researchers. London: Sage, 2003.

Millar K, Asbury A J, Bowman A W, Hosey M T, Musiello T, Welbury R R . The effects of brief sevoflurane-nitrous oxide anaesthesia upon children's postoperative cognition and behaviour. Anaesthesia 2006; 61: 541–547.

Hosey M T, Macpherson L M, Adair P, Tochel C, Burnside G, Pine C . Dental anxiety, distress at induction and postoperative morbiditiy in children undergoing tooth extraction using general anaesthesia. Br Dent J 2006; 200: 39–43.

Albadri S, Jarad F D, Lee G T, Mackie I C . The frequency of repeat general anaesthesia for teeth extractions in children. Int J Paediatric Dent 2006; 16: 45–48.

NHS. NHS Dental Statistics England 2015-16. 2016 http://content.digital.nhs.uk/catalogue/PUB21701/nhs-dent-stat-eng-15-16-rep.pdf (accessed November 2016).

Nutbeam D . Evaluating health promotion: progress, problems and solutions. Health Promo Int 1998; 13: 27–44.

Amin M S, Harrison R L . Understanding parents' oral health behaviours for their young children. Qual Health Res 2009; 19: 116–127.

Michie S, Van Stralen M M, West R . The behaviour change wheel: A new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement Sci 2011; 6: 42.

Wood C E, Hardeman W, Johnston M, Francis J, Abraham C, Michie S . Reporting behaviour change interventions: Do the behaviour change technique taxonomy v1, and training in its use, improve the quality of intervention descriptions? Implement Sci 2011; 11: 84.

Redmond C A, Blinkhorn F A, Kay E J, Davies R M, Worthington H V, Blinkhorn A S . A cluster randomized controlled trial testing the effectiveness of a school-based dental health education program for adolescents. J Public Health Dent 1999; 59: 12–17.

Humphris G M, Field E A . The immediate effect on knowledge, attitudes and intentions in primary care attenders of a patient information leaflet: a randomized control trial replication and extension. Br Dent J 2003; 194: 683–688.

Arora A, Mcnab M A, Lewis M W, Hilton G, Blinkhorn A S, Schwarz E . 'I can't relate it to teeth': A qualitative approach to evaluate oral health education materials for preschool children in New South Wales, Australia. Int J Paediatric Dent 2012; 22: 302–309.

Kowash M B, Pinfield A, Smith J, Urzon M E J . Dental health education: Effectiveness on oral health of a long-term health education programme for mothers with young children. Br Dent J 2000; 188: 201–205.

Blinkhorn A S, Gratix D, Holloway P J, Wainright-Stringer Y M, Ward S J, Worthington HV . A cluster randomised, controlled trial of the value of dental health educators in general dental practice. Br Dent J 2003; 195: 395–400.

Harris C E, Chestnutt I G . The use of the Internet to access oral health-related information by patients attending dental hygiene clinics. Int J Dent Hygiene 2005; 3: 70–73.

Riordian R N, Mccreary C . Dental patients' use of the Internet. Br Dent J 2005; 207: 583–586.

Chestnutt I G, Reynolds K . Perceptions of how the Internet has impacted on dentistry. Br Dent J 2006; 200: 161–165.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed Paper

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivs 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Ogretme, M., AbualSaoud, D. & Hosey, M. What preventive care do sedated children with caries referred to specialist services need?. Br Dent J 221, 777–784 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2016.951

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2016.951