Key Points

-

Improved awareness of ASA PS Classification as a tool for assessment and communication between settings.

-

Exploration of ASA PS strengths and limitations for dentists and anaesthetists in everyday practice.

-

Increased knowledge of alternative medical and dental patient risk assessment tools.

Abstract

Background Medical risk assessment is essential to safe patient management and the delivery of appropriate dental care. The American Society of Anesthesiologists Physical Status (ASA PS) Classification is widely used within medicine and dentistry, but has received significant criticism. This is the first UK survey to assess the consistency of medical risk assessment in dentistry.

Aims (i) To determine the use and consistency of the ASA PS among dentists and anaesthetists. (ii) To consider the appropriateness of the ASA PS in relation to dental treatment planning and delivery of care.

Method A cross-sectional online questionnaire was distributed to anaesthetists and dental practitioners in general practice, community and hospital dental services. Questions focused on professional backgrounds, use of the ASA PS, alternative approaches to risk assessment in everyday practice and scoring of eight hypothetical patients using ASA PS.

Results There were 101 responses, 82 were complete. Anaesthetists recorded ASA PS score more frequently than dental practitioners and found it more useful. Inconsistencies were evident in the assignment of ASA PS scores both between and within professional groups.

Conclusion Many dental practitioners did not use or find ASA PS helpful, with significant inconsistencies in its use. An awareness of alternative assessment scales may be useful across settings. Accepting its limitations, it would be helpful for all dentists to be educated in ASA PS and its use in medical risk assessment, particularly in relation to conscious sedation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Recent years have seen an increase in life expectancy resulting from the advancements in healthcare.1 Patients now attend for dental examination and treatment with more complex medical histories, often reporting multiple co-morbidities2 and polypharmacy.3 Patient risk assessment is therefore essential to their safe management and the delivery of appropriate dental care.

Within medicine, risk prediction tools are widely used and contribute towards clinical decision making.4 Many of these tools focus on the overall physical status of the patient, although some are more specific to the physiological and operative management of a particular disease or procedure.5

One of the most widely accepted assessment tools in medicine and dentistry is the American Society of Anesthesiologists Physical Status (ASA PS) Classification.6

ASA PS was introduced as a system for the collection and tabulation of statistical data in anaesthesia7,8 aimed at linking operative risk and prognostic outcomes of surgery. It was found, however, to be dependent upon too many variables, such as the planned operative procedure, the skill of the surgeon, attention to post-operative care and the experience of the anaesthetist.7,8

The classification offered a method of recording the overall physical status of a patient before surgery and aimed to encourage adoption of common terminology that would make statistical comparisons possible across settings and medical literature.7,8 This has been subsequently modified to the more familiar 6-point scale used today (Table 1).

This classification is used extensively in medicine not only for anaesthetic assessment, but for performance evaluation, clinical research and to inform policy making. In dentistry it is used to summarise patients' general health, though more often used in patients receiving dental treatment under conscious sedation. Recent guidance9 states that dentists who undergo training in conscious sedation techniques are expected to know the relevance of the patient's ASA status and this should be documented in the patient's record.10 Although not mentioned in the guidance, it is generally accepted that dental patients who are ASA III or graver are not suitable for the provision of conscious sedation in primary care.11 Despite this it is acknowledged that some Community Dental Services (CDS) may treat patients with additional needs in primary care that are considered to be ASA III.

Despite its popularity, ASA PS has received criticism regarding the accuracy and usefulness of information that it yields.7,12,13

Aims

This paper aims to determine the use and consistency of the ASA PS among dentists and anaesthetists, and consider the appropriateness of the ASA PS in relation to dental treatment planning and delivery of care.

Method

An online link to a cross-sectional questionnaire (Fig. 1) was disseminated via e-mail to a global list of anaesthetists and dentists across London including general dental practitioners (GDPs), hospital dental practitioners (HDPs), and community dental practitioners (CDPs). The questionnaire sought to collect information about the professional backgrounds of the respondents and their use of the ASA PS Classification or other approaches to patient assessment in everyday practice. Prior to this, a pilot questionnaire was distributed to two representatives from each professional group to minimise the risk of errors, in addition to ascertaining face and content validity.

For dentists, questions also focused on experience in conscious sedation and the classifications of patients that they felt would be most appropriately treated in primary or secondary care settings. For anaesthetists, this extended to questions relating to experience of working with dental teams and their perception of the accuracy of dentists using ASA PS scores.

The final section asked respondents to give their ASA PS scores to hypothetical patients. Following feedback from the pilot questionnaire, eight scenarios with varied medical histories were considered sufficient to show an outcome for this investigation.

In order to maximise the number of responses obtained, the link was sent on three occasions through the mailing list. Although the survey was anonymous, participants were prevented from responding more than once from the same e-mail account by software.

Results

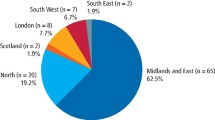

One hundred and one responses were initially received, of which 82 were complete. The professional backgrounds and number of respondents from each group are demonstrated in Table 2.

The largest group assessed were the HDPs. Practitioners from all disciplines and stages of professional development ranging from dental core trainee through to consultant level were included. The GDP group was comprised of those recently qualified, in addition to more experienced practitioners, and CDPs ranged from dental officer to senior dental officer. The majority of the anaesthetist group were very experienced at specialist registrar or consultant levels. This is demonstrated for all groups by the spread of years in holding a primary qualification.

The ASA PS was used most frequently by anaesthetists, with a minority reporting never using it (5.3%, n = 1). Most GDPs reported never using this tool (80.0%, n = 20), with many stating that the ASA PS was not useful (56.0%, n = 14). Approximately a third of HDPs (33.3%, n = 13) and CDPs (29.4%, n = 5) also agreed that the use of ASA PS Classification was not helpful in daily practice.

A large proportion of HDP (50.0%, n = 20) and CDP (52.9%, n = 9) groups were involved in the delivery of dental treatment under conscious sedation. These practitioners tended to find the ASA PS somewhat helpful, although only a small proportion reported always documenting the score in the patient's records (7.5%, n = 3 and 5.8%, n = 1 respectively), suggesting low compliance with guidance10 in relation to record keeping.

Dental practitioners from across settings had little awareness of other physical assessment scales (9.8%, n= 8) compared to anaesthetists (47.4%, n = 9).

GDPs were asked which ASA PS scores they felt should be suitable for treatment in the CDS. Many (54.6%, n = 29 combined responses) felt that ASA PS I and II patients were suitable for referral to this setting. A number (41.6%, n = 22 combined responses) believed that ASA PS III and IV were suitable. A small proportion felt that scores of V and VI were also suitable (3.8%, n = 2 combined responses). Similar results were also seen among members of the CDS and Hospital Dental Service (HDS) regarding ASA scores considered appropriate for treatment under conscious sedation in the dental hospital environment (Fig. 2 and Fig. 3).

All anaesthetists taking part in the study worked regularly with various dental teams, most commonly adult oral surgery (52.6%, n = 10), and least frequently adult special care dentists (15.8%, n = 3). Most of them felt that dentists were able to correctly assign ASA PS most of the time or sometimes (Table 3).

Participants were requested to assign an ASA grade to eight hypothetical patients, which showed considerable variation in results, not only between professional groups, but also within the same groups as summarised in Table 4.

Discussion:

Eighty percent of GDPs (n = 20) never recorded patients ASA PS in the medical history compared to 94.7% of anaesthetists who always (68.4%, n = 13) or sometimes (26.3%, n = 5) documented this. Thirty five percent (n = 6) of CDPs and 55.0% (n = 22) of HDPs never recorded ASA PS scores.

A substantial proportion of anaesthetists within this study felt that dentists were only sometimes or not able to assign an accurate ASA score to patients, although the reason for this assumption is unclear. Inconsistencies were evident among anaesthetists, suggesting that this is likely due to inter-operator variability following the subjectivity of the classification, rather than a difference in applied clinical knowledge.

A particularly low response was received in relation to participant awareness of alternative physical assessment tools. This may be due to a lack of awareness, or the question may have been overlooked by respondents. Suggestions included Mallampati Score, Body Mass Index, Performance Status and the Goldman Index. Learning disability scales were also highlighted, but tended to relate to patient cognitive assessment, which has implications for consent rather than medical risk assessment.

An awareness of alternative assessment tools (Table 5) may be important when determining medical risk prediction, especially in a hospital and community setting where it can form the basis of inter-professional communication.

The majority of GDPs felt that patients of ASA PS I-III were appropriate for treatment under conscious sedation in the CDS. However, as CDS is a primary care service, it is not necessarily considered an appropriate setting for delivery of conscious sedation for those graded III and IV.11

A small proportion of GDPs indicated that they would consider referring patients up to score V (moribund) and VI (brain dead), both in the absence and presence of an anaesthetist to provide conscious sedation in the dental hospital environment, highlighting the lack of knowledge of the ASA PS scale. The ASA PS scale should therefore be used with caution as a means of communication with GDPs. Verbal feedback further emphasised this lack of awareness among GDPs following distribution of the questionnaire.

GDPs did not differ in their ASA PS referral criteria to Community and Hospital Dental Services for conscious sedation, indicating the potential for inappropriate referrals to CDS and secondary care. Additionally, this would suggest that some GDPs are not aware that, generally, only ASA I and II patients are suitable for treatment in primary dental care11. Ultimately, such confusion will potentially make it difficult for the commissioners of sedation services in dentistry.

In relation to the assignment of ASA PS scores to eight hypothetical patients, this study did not seek to compare responses to a predetermined correct answer in any of the cases, since the level of agreement between professionals is the closest estimation of the most suitable score.13 In all instances, considerable variation was shown between and within each professional group, however, the anaesthetists tended to be more consistently in agreement. For seven of eight hypothetical patients, the predicted ASA PS scores spanned four or more categories.

There are a number of potential reasons for such variation which can be explored using the example of scenario 8: 57-year-old male with a history of alcohol dependency, liver cirrhosis and mild asthma triggered by moderate exercise. Responses for this scenario spanned from ASA I (normal healthy patient) to ASA V (moribund), suggesting a general lack of awareness of the meaning of each ASA PS score. Taking the highest proportion of answers as the closest approximation of the most suitable score, this scenario would be ASA PS III. The ASA PS Classification has previously described ASA III as 'severe systemic disease that limits activity, but is not incapacitating'.14 However the term 'incapacitating' has been highlighted as poorly defined, open to interpretation and therefore a source of variability.12 This ambiguous term has now been removed from the classification,6 however, respondents may be unaware of this change and have difficulties interpreting what constitutes 'severe disease'. Therefore, they may have scored with uncertainty due to the broad nature of the ASA PS categories.

Within the professional groups, respondents have different knowledge bases, with some perhaps thinking beyond the information provided in the scenario. For example, some may think of the co-morbidities associated with liver cirrhosis such as portal hypertension and encephalopathy, which may influence their decision making. In these hypothetical scenarios, respondents were unable to ask patients further questions or consult with medical professionals, however, in the clinical situation this could influence scoring.

Variations were not apparently related to years of experience, which is in agreement with findings from a number of external studies,12,13 suggesting that education in ASA PS would be beneficial at all levels of each professional group.

Investigations conducted among anaesthetists have highlighted subjectivity and poor reproducibility of the ASA PS Classification.7,12,13,25 Specific studies among dental practitioners are lacking, although variability among dental practitioners has been shown when compared to a computer model.26

There are inherent difficulties associated with the subjective nature of this scale.25 It does not include factors such as age, sex, weight, pregnancy, intended surgery, expertise of the anaesthetist or surgeon, degree of pre-surgical preparation or the facilities for postoperative care. The term 'systemic' can be misleading since local disease can cause a significant change in physical status, but is not included in the classification.27 Patients may also fluctuate between ASA PS scores depending on the management of their disease.

From a dental perspective, anxiety related to examination and treatment can have a substantial effect on underlying medical co-morbidity. This should be taken into consideration when assessing a patient's physical status, however, should not affect the ASA PS score. Consequently a number of dental physical assessment tools have been developed (Table 6).

Dental practitioners in this study did not demonstrate any knowledge of dental specific risk assessment tools. They have not become widely adopted within dentistry, possibly due to problems brought by the subjective foundation of the ASA PS Classification or simply a lack of awareness.

Limitations

The comparatively small sample has its limitations. Equal proportions of professional groups would have been more ideal, but based on the demographic information of the participants, it is believed that the responses adequately represent the views of the professional groups desired in the sample.

ASA PS has been evaluated among dentists in one previous investigation only.26 It is not possible to directly compare results from this study due to differences in methodologies.

Due to the online basis of the questionnaire, it is possible that participants may have used online resources or collaborated to inform in their decision making, which may not be possible in the clinical situation. Technical errors in saving responses could have also reduced the response rate.

This study could be expanded to explore the rationale behind the ASA score decision making process among professionals and reasons for scoring variability, perhaps on a qualitative basis.

Conclusion

Many dental practitioners do not find ASA PS Classification helpful and a poor understanding was demonstrated. There is a lack of consistency in the use of the ASA PS between and within different dental and anaesthetist groups. This does not seem to be related to professional development, but is more so due to the inherent subjective nature of the classification. This may lead to confusion among some GDPs as to where they can appropriately refer patients.

An awareness of alternative medical risk assessment scales may be useful, particularly when communicating with other teams involved in patient care. However, there is a poor general awareness among dental professional groups. Adoption of an assessment tool incorporating dental anxiety may be more relevant to patients requiring conscious sedation within the dental setting. This would not only apply to clinical risk assessment, but also the wider considerations of research, service development and performance evaluation.

In summary, accepting its limitations, it would be helpful for all dentists to be educated in the use of ASA PS Classification and its application in medical risk assessment, particularly in relation to conscious sedation.

References

Office for National Statistics. Population aging in the United Kingdom and its constituent countries and the European Union. 2012. Available online at http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/rel/mortality-ageing/focus-on-older-people/population-ageing-in-the-united-kingdom-and-europe/rpt-age-uk-eu.html (accessed January 2016).

Greenwood M, Jay R H, Meechan J G . General medicine and surgery for dental practitioners. Part 1 – the older patient. Br Dent J 2010; 208: 339–342.

Carter L M, McHenry I D S, Godlington F L, Meechan J G . Prescribed medication taken by patients attending general dental practice: changes over 20 years. Br Dent J 2007; 203: E8.

Chhabra B, Kiran S, Malhotra N, Bharadwaj M, Thakur A . Risk stratification in anaesthesia practice. Indian J Anaesthesia 2002; 46: 347–352.

Surginet. Risk prediction in surgery. 2016. Available online at http://www.riskprediction.org.uk/ (accessed January 2015).

American Society of Anesthesiologists. ASA Physical Status Classification System. 2014. Available online at http://www.asahq.org/resources/clinical-information/asa-physical-status-classification-system (accessed January 2016).

Fitz-Henry J . The ASA classification and pre-operative risk. Ann Royal Coll Surg Eng 2011; 93: 185–187.

Saklad M . Grading of patients for surgical procedures. Anesthesiology. 1941; 2: 281–284.

Intercollegiate Advisory Committee for Sedation in Dentistry. Standards for Conscious Sedation in the Provision of Dental Care. 2015. Available online at http://www.rcseng.ac.uk/fds/publications-clinical-guidelines/docs/standards-for-conscious-sedation-in-the-provision-of-dental-care-2015 (accessed January 2016).

Society for the Advancement of Anaesthesia in Dentistry. The Safe Practice Scheme. A quality assurance programme for implementing national standards in conscious sedation for dentistry in the UK. 2015. Available online at http://www.saad.org.uk/images/Linked-Safe-Practice-Scheme-Website-L.pdf (accessed January 2016).

Craig D . Skelly M . Chapter 4: Initial assessment and treatment planning. In Practical conscious sedation, first edition. pp 52. London: Quintessence Publishing Co. Ltd, 2004.

Aronson W L . McAuliffe M S . Miller K . Variability in the American Society of Anesthesiologists Physical Classification Scale. Am Assoc Nurse Anaesth 2003; 74: 265–274.

Burgoyne L . Smetzler M P . Pereiras, L A, Norris A L . De Aremendi A J . How well do paediatric anesthesiologists agree when assigning ASA physical status classifications to their patients? Paediatr Anaesth 2007; 17: 956–962.

American Society of Anesthesiologists. New classification of physical status (Editorial). Anesthesiology 1963; 24: 111.

Mallampati S R . Gatt S P . Gugino L D et al. A clinical sign to predict difficult tracheal intubation: a prospective study. Can Anaesth Soc J 1985; 32: 429–34.

Albouaini K . Egred M . Alahmar A . Wright D J . Cardiopulmonary exercise testing and its application. Postgrad Med J 2007; 83: 675–682.

Scott S . Lund J N . Gold S et al. An evaluation of POSSUM and P-POSSUM scoring in predicting post-operative mortality in a level 1 critical care setting. BMC Anaesthesiology 2014; 14: 104.

Nashefa S A M . Roquesb F . Hammill B G et al. Validation of European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation (EuroSCORE) in North American cardiac surgery. Euro J Cardio-Thoracic Surg 2002; 22: 101–105.

Goldman L, Caldera D L, Nussbaum S R . Multifactorial index of cardiac risk in noncardiac surgical procedures. New Eng J Med 1977; 297: 845–850.

New York Heart Association. Classes of Heart Failure. 2015. Available online http://www.heart.org/HEARTORG/Conditions/HeartFailure/AboutHeartFailure/Classes-of-Heart-Failure_UCM_306328_Article.jsp (accessed January 2016).

Karnofsky D A . Burchenal J H . The clinical evaluation of chemotherapeutic agents in cancer. evaluation of chemotherapeutic agents, first edition. pp 196. Columbia University Press: Columbia, 1949.

Oken M . Creech R H . Tormey D C . Toxicity and response criteria of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. 1982. Am J Clin Oncol 1982; 5: 649–655.

Allman K, Wilson I (eds). Chapter 5: Respiratory Disease. In Oxford Handbook of Anaesthesia,third edition. pp 100. Oxford University Press: Oxford, 2011.

World Health Organization. BMI Classification. 2015. Available online at http://apps.who.int/bmi/index.jsp?introPage=intro_3.html (accessed January 2016).

Sankar A . Johnson S R . Beattie, W S, Tait G . Wijeysundera DN . Reliability of the American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status scale in clinical practice. Br J Anaesth 2014; 113: 424–432.

De Jong K J M, Oosting J, Abraham-Inpijin L . Medical risk classification of dental patients in the Netherlands. J Pub Health Dent 1993; 53: 219–222.

Daabiss M . American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status classification. Ind J Anaesth 2011; 55: 111–115.

McCarthy F M, Malamed S F . Physical evaluation system to determine medical risk and indicated dental therapy modifications. J Am Dent Assoc 1979; 99: 181–184.

Goodchild J . Glick M . A different approach to medical risk assessment. Endo Top 2003; 4: 1–8.

Fehrenbach M . ASA Physical Status Classification System for Dental Professionals. 2015. Available online at http://www.dhed.net/ASA_Physical_Status_Classification_SYSTEM.html (accessed January 2016).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank everyone who took the time to take part in this study. Without such kind assistance, this work would not have been possible.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed Paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Clough, S., Shehabi, Z. & Morgan, C. Medical risk assessment in dentistry: use of the American Society of Anesthesiologists Physical Status Classification. Br Dent J 220, 103–108 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2016.87

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2016.87

This article is cited by

-

Oral sedation in dentistry: evaluation of professional practice of oral hydroxyzine in the University Hospital of Rennes, France

European Archives of Paediatric Dentistry (2021)

-

Preprocedural Assessment for Patients Anticipating Sedation

Current Anesthesiology Reports (2020)

-

Evaluation of cardiac risk in dental patients

British Dental Journal (2018)