Key Points

-

Describes how dental practice has become stratified with the emergence of 'dental elites' who represent practitioners to commissioning authorities.

-

Argues that a greater degree of distributed clinical leadership is necessary to defuse tensions between the micro (clinical) and macro (policy) level.

-

Suggests that there is a need to consider ways to develop practitioner clinical engagement.

Abstract

Aim While doctors are moving centre-stage into managerial and leadership commissioning roles, the role of clinicians in NHS dental commissioning has retained a mainly representative model. In this paper we describe the discourse of 'rank and file' dental practitioners and the implications of this for clinical engagement and clinical leadership in dentistry.

Method As part of an NIHR study of NHS dental contracting a questionnaire was sent to 925 practitioners. The questionnaire included a free text box inviting further comment. We received 113 lengthy narratives in 333 (43%) of the questionnaires returned and so undertook a discourse analysis of this data - focusing on the use of language, shared meaning and how practitioners portrayed their identity and activities.

Results Three discursive repertoires were identified: professional subordination; a disconnected hierarchy; and a strained collegiality. Underpinning these repertoires was the sense of disjuncture between the macro-level (managerial) and micro-level (practice), and the problematic nature of clinical leadership in a profession where dentists' common identity is fractured by their individual clinical and business practice.

Conclusions This paper presents an insight into the views of dental practitioners in their own words, and the challenges of engaging dental practitioners in a new commissioning era.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

A profession – medicine, or dentistry, is often taken as an archetype of this model1 – is often defined as being a special kind of occupation characterised as having the right to control its own work.2 This autonomy though, is not the same as that say, of circus jugglers and magicians who possess de facto autonomy by virtue of the esoteric or isolated nature of their work. Rather, professions are deliberately granted autonomy, including the right to determine who can legitimately do its work and how the work should be done.2 Parsons extends this further, by arguing that professions are therefore characterised by universalism, neutrality and homogenity, since once any individual has gained the prescribed accreditation, they should be treated as 'equal' to their colleagues by members of the profession.3

In the NHS, a quasi-market in health care has been in existence since the 1990s.4 However, a separation of purchasers (or commissioners) from providers of health care, originally intended to bring incentives to efficiency and cost effectiveness to a monolithic and bureaucratic public sector, is increasingly recognised as having limitations in the health care context.4 Hence the UK healthcare market has been more accurately described as 'reputational' and relational, than one based on pure economic principles.5 And this places a strain on one of the basic features of the medical profession, because competition undermines its collective collegiality. UK dentistry is already fragmented, and partially insulated from the rest of the NHS, by nature of its system of dental practice which is based on a sub-contracting arrangement where dental practitioners own their own businesses and premises and are reimbursed by the state for services they provide.4 A system based on commissioning in UK dentistry therefore presents particular challenges.

Commissioning is intended to be the means by which health care resources and demands can be brought into some sort of balance, achieving the 'best value' for patients and tax payers.6 While strong commissioning is put forward as a means of optimising efficiency and as an essential antidote to supplier-induced demand, experiences of NHS commissioning are often rather different, and disappointing. Smith et al.,7 for example, identify that, too often, the commissioning process 'plays at the margins'. Likewise, commissioning in dentistry appears to have been slow to live up to its promise - being hitherto mainly preoccupied in dealing with difficult contractual issues, rather than with undertaking commissioning in its true sense.8 These shortfalls have now been recognised, leading to NHS commissioning being significantly re-structured in recent years.

And so a new commissioning era in dentistry has now begun. Local commissioning by primary care trust (PCT) commissioners has been replaced with a more centralised system supplemented with greater clinical involvement with strategic decision making at a local level,9 and hopes are high that these latest changes will address some of the fundamental flaws recognised in the previous system – a lack of consistency in dental commissioning decisions taken at a local level, and an under-representation of the clinical view when strategic commissioning decisions were made.8 Whether these latest reforms are any the more likely to yield the kind of benefits envisaged by a system involving commissioning, however, is still open to debate.

In an NIHR funded study of NHS general dental practice contracting we observed that NHS dental commissioning was heavily tied up with dental contracting issues as well as with the negotiation of wider managerial/professional tensions.4,10,11 This three-year study included a questionnaire to dental practitioners which investigated their relationships and dealings with local commissioners, involvement with professional networks and their interpretation of the current NHS dental contract.11 At the end of the questionnaire there was a free text box allowing respondents to express further thoughts, and because just under a third of respondents provided lengthy written comments in response to this invitation, we felt this wealth of data merited some in-depth analysis. Although there is a range of possible methodological approaches to analysing free text questionnaire data such as this,12 we opted to use a discourse analysis approach due to the large number of lengthy and complex narratives available to us. It is important though to still bear in mind that the data was generated in the context of a questionnaire topic focusing on NHS dental commissioning and contracting experiences.

Discourse analysis is a term that in itself covers a range of rather different approaches to qualitative data analysis,13 although they all have in common a general focus on the interaction between people and what is happening naturally, based on the principle that discourse is a fundamental medium for human action.14 Discourse portrays common understandings and ways of acting – expressing 'who and what is normal, standard and acceptable',15 so discourse analysis often involves examining conversations between people which are not staged, as they would be say, in an interview situation. Discursive repertoires are identified, which are a cluster of terms, categories and idioms that are closely conceptually organised.14 They portray the creation and maintenance of social norms, the construction of personal and group identities and the negotiation of social and political interaction.16 Discursive repertories can be revealed not just in analysis of conversations, but in a content analysis of text such as newspaper reports, and even free text as in our dataset. In this article therefore we outline the discursive repertoires of dental practitioners identified from their comments given as free text in a questionnaire on the factors which influence practitioners' responses to NHS dental contracts.

Method

National research ethics approval (reference number 10/H1011/38) and NHS research governance approvals were obtained for the study. Questionnaires were sent by post to a cluster sample of 924 dentists (all owners of their practice) drawn from 14 PCTs across England. Lists of the names and addresses of dental practice owners were obtained from Care Quality Commission lists of providers of dental care (which included solely private as well as NHS providers). After three mailings between January and May 2013, 393 questionnaires were returned (43%). Quantitative questionnaire data were entered SPSS (version 20) and free text comments from 113 questionnaires entered into NVIVO (version 10).

The analysis of free text data involved identifying broad themes and functions of the language used, focusing upon 'language above the level of the sentence'.13 Analysis involved three aspects: immersion in the language itself, scrutiny of any variability and inconsistency of meanings between participants, and considering the implications of the account given and what the discourse set out to achieve.17 Analysis was undertaken by a dental and two non-dental researchers with emerging interpretations discussed within the analytic team. It involved the coding of the written extracts into themes which were then shaped into discursive repertoires by coding and recoding in the course of the analysis as understanding of the data deepened.

Results

Almost a third of respondents (29%, 113) provided comments at the end of the questionnaire. Twenty of these free text comments were provided by solely private practitioners. There were no significant differences in the demographic characteristics of those giving additional text compared with those not adding comments: 39% (41) of respondents who provided comments had practices with more than 90% of an NHS workload, compared to 56% (54) of practitioners not commenting, (p = 0.28). Likewise, those giving comments were not significantly more likely to be engaged in professional activity outside their dental practice: 20% (20) reported attending dental meetings outside their practice more than once in the last month, and 40% (22) were involved in a PCT advisory group, compared to 16% (39) and 60% (33) respectively of those not offering additional comments (p = 0.26 and p = 0.08).

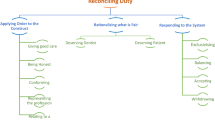

Three discursive repertoires were identified from the data: a) professional subordination; b) a disconnected hierarchy; and c) a strained collegiality – all expressions of a feeling of disconnect which presents challenges to the new vision of an increase in collaborative commissioning and clinical engagement in the strategic development of dental services.

Professional subordination

Practice owners portrayed their identity through their comments, as in a subordinate position to managerial influence (local commissioners as well as central policy and regulatory managerial influence). This is strikingly different from the usual picture of managerial/professional struggle where professionals (albeit 'embattled'), tend to retain their power.18 Far from the usual ongoing competition for public legitimacy between professionals and managers (often seen as a 'discursive game' where each party continues to argue their case for ascendency in an effort to exert control), dentists portray commissioners as having the ascendency by possessing 'structural power' through their control of the public purse and ability to unilaterally implement sanctions. The discourse exhibited in the narratives is one of vulnerability and chastisement embedded within a superior-subordinate relationship:

'After recent claw-back meeting I really felt like a silly little girl, not a 46-year-old business-owning dental professional'. (III3)

'I suspect whoever came up with them [regulations] tried to make them as ambiguous as possible (perhaps with the intention of tripping up providers when the day of judgement comes). As hard as I have tried I am sure I will have fallen foul of them. More concerning is that I hear that 'errors' are not picked up as they occur and performers informed of mistakes, but they are allowed to continue, and accumulate, again to be answered for on judgement day'. (I30)

The use of positional power by commissioners is typical of a managerial leadership style,19 and appreciated less by participants than influence based on personal power – that is, perceived credibility (involvement in clinical work), integrity and years of experience in both clinical work and running a business. Owning a business, being a dental professional and acquiring experience of both roles over time were seen as the appropriate route to prestige and influence. Dentists expressed dismay that personal power had so little currency in the leadership at the present time.

'The last dental contract is/was a total disaster and the future pilot one heading in completely the wrong direction. It would be simple to write the only way forward but hey, 30+ years of experience is being ignored'. (III61)

Disconnected hierarchy

A disconnect between the dental professional and managerial view was seen in the way dentists' constructed their notions of 'good care' and 'fair return'. 'Good care' in the eyes of practitioners was heavily contextualised by micro-level (practice) constraints (what was 'practically possible and affordable'). Dentists identified these practice constraints as growing – rising costs of outgoings such as laboratory fees and the ever increasing demands of a tighter regulatory framework. Dentists' judgements on what constituted 'fair care' were drawn more heavily from what was recognised as appropriate by peers and patients, than from the viewpoint of commissioners.

'Dentists have always been independent practitioners within the NHS, and the relative freedom to carry out professional care in a way you see fit (within obvious legal and professional guidelines) is very dear to many who wish to be judged by their patients and peers not by a PCT commissioner whose knowledge of clinical practice is negligible'. (IV86)

Freidson20 identifies the 'macro' (population level) and 'micro' (clinical care of individual patients) perspectives as a major line of cleavage within the medical profession and that there are bound to be tensions when standards defined say at the macro-level by academics and managers are incongruent with the micro-level. Certainly the discourse of practitioners seems tolerant to some degree of compromise in quality when resources are squeezed at the practice level. Dentists' portrayed the defining of 'quality' as an ongoing problem-solving dynamic, rather than an outlining of absolutes. Thus clinical dentistry is no different to other types of professional work which consists of solving problems that present as 'messy indeterminate situations.21 Acceptable quality standards for clinical work appeared to be both individually and collectively identified, with clinical colleagues united in a continuous and mutual process of 'knowing-in-action' and 'reflection-in-action' through their repertoire of common practice experiences.21 While practitioners gave a sense of being aware of a dilution of the quality of care provided to patients among their peers, they tended to suspend overt public judgement of their colleagues' conscientiousness and ethics of practice. Dentists though were dismissive where quality considerations were seen as being tacitly ignored in order to maintain managerial and financial targets, and commissioning was often depicted as insufficiently cognisant of pressures at the practice level.

'When the NHS does not allow for business development and has perverse incentives, you cannot expect the practitioner to ignore the business implications and it cannot be a surprise that the needs of the patient sometimes are compromised'. (I45)

'Practice expenditure increased by 17% over the last three years. Contract value increased by 2.125% over same period! Enough said. Either quality of care is reduced or contract values must increase substantially to close this gap'. (V9)

'Totally unachievable – patients no longer receive the proper treatment. Dentists have always played the game and will always do so'. (V57)

That is not to say that 'fairness' and 'acceptable care' are not closely guarded social norms of dentists – they are. Professional standards are acknowledged, but judgement on what is 'fair' and 'acceptable' appears valued most when it is made by patients and peers.

'It is all far too complex and dentists do what they like with impunity. As the contract stands nobody should be refusing a patient if they cost too much. But it happens all the time... it needs to be properly controlled so that everybody takes their share of loss making patients'. (XIV9)

The disconnected hierarchy (where there is a disjunction between those delivering front-line services and those responsible for front-line management) is typical of other examples in health care.19 Paradoxically, an inverted power structure appears to exist, where those at the bottom (practitioners) have a greater influence over decision making on a day-to-day basis, than commissioners who are nominally in control at the 'top'. Discretion rather than prescription appears a key feature of dental work because this complex clinical decision making environment is not readily be reduced to a formulaic solution. This leaves considerable scope for adaptation at the micro-level. A highly selective connection up and down the hierarchy (between the practice and commissioning level – but only between some providers and commissioners) leaves the system open to exploitation.

'It is scandalous that practitioners advertise NHS availability and then refuse to do these items [scale and polish, white fillings]. The practice of avoidance is extremely widespread (Channel Four, Dispatches programme), but nobody is doing anything about this?' (II84)

'No matter how experienced the practitioner, it colours your judgement. Being older with patients I have treated for years keeps my judgement sound'. (IV38)

'Most corporates are screwing the system for profit and have the PCTs wrapped around their little fingers, very similar to the Southern Cross affair in elderly care'. (IV47)

Strained collegiality

The existence of a disconnected hierarchy opens up the possibility of different relationships between commissioners and practitioners characterised by some dentists as an uneven playing field with 'insiders' and 'outsiders'. Some practitioners (the 'insiders') were seen as being in a clique with commissioners and able to exploit this relationship to their own advantage. These cliques were felt to exclude other practitioners - the 'outsiders', who saw their exclusion as unjust. From an outsider perspective there were a number of benefits that insiders accrued; most notably, preferential treatment in contract awards and less scrutiny in terms of the delivery of work.

'There is also a sense of 'favouritism' in the area. Certain practices awarded contracts that weren't tendered and LDC did not 'have the balls' to challenge it as the practice owner was on the LDC'. (XI15)

'I have felt distressed about being outside the PCT 'information loop'. Contracts are continually awarded to a parade of secondary care providers who are 'here today and gone tomorrow'. Quality assessment of such providers is very difficult to assess'. (IX50)

While on the one hand practitioners appeared to value a clinical involvement in commissioning by 'senior' practitioners in the profession, they also pointed to an obvious conflict of interest which existed, for example when practitioners in the 'inner circle' of commissioning discussions, held NHS dental contracts themselves. The clinical 'elite' were seen as holding competing (and sometimes incompatible) responsibilities when acting as both leaders and clinical providers.19

'In our area, these over-treating dentists have seen their practices thrive [under the UDA system] as their lab bills plummeted. They have become dental practice advisors or risen to high office in the Deanery. This means that they will have huge advantage when the new contracts are handed out. The PCT can't see anything wrong with one of their dental practice advisors being employed by a dental practice chain that had been awarded huge contracts. He now has a prestigious University post. One dentist now in high office once gave us a lecture about how to split treatments over several band two courses!'. (VII54)

Discussion

This paper draws on the views of a high number of self-selected participants who have offered views on their experience of working as a dental practitioner. As with most qualitative research though, there is no basis for claims of a wider generalisation – those both completing the comment section and returning their questionnaire inevitably represents practitioners with particularly strong views on the way dental commissioning and contracting is conducted. The professional identities constructed in the discourses available to us therefore reflect the desire of some practitioners to articulate concerns about the way dentistry is commissioned. Moreover, we must note that what is described here is our construction of the identity construction of others, and, as with any type of qualitative research; our interpretation inevitably carries a degree of subjectivity. Nevertheless, running through the dataset available to us, was a theme of a discourse of disconnection – between the clinical and managerial, and between the 'rank and file' practitioner and the so-called clinical 'elites'. Since recent reforms have identified increased clinical engagement as an essential way forward in the new commissioning era, our data raises concerns as to whether new models of clinical representation (in the form of Local Dental Networks (LDNs)),9 will adequately meet the need for greater clinical involvement in commissioning decisions.

Our data depicts the dental profession as more of an aggregate of individual professionals, than corporate in nature – with practitioners bound together through their professional identity, but fractured through their individual clinical and business practice. Though a certain level of stratification is in evidence (those in 'high office') – with elites being dentists who hold roles at a range of levels (local dental committees, LDNs, professional associations), the 'rank and file' hold concerns that open competition means that truly clinical dental leaders are conflicted. Thus, as observed by Edmonstone,19 the very notion of clinical leadership is contested. There is a risk that clinical leadership becomes merely an instrumental means to managerial ends and restricted to operational matters which are largely cosmetic - merely tokenism. Relying on dental clinical elites in the form of LDN representation might also be insufficient to bridge the micro and macro level disconnect apparent in our data. To move beyond tokenism, a means of connecting with the wider 'rank and file' practitioner in order to harness peer pressure to maintain standards, looks necessary. Thus while the need for clinical engagement has been recognised, there is little guidance on exactly that should look like, or how best it can be achieved.19 Certainly, a greater involvement of practitioners in commissioning decisions is necessary, but probably not sufficient. What appears needed is a greater clinician-to-clinician dialogue and agreement on 'efficient', 'affordable' and 'appropriate' care looks like in dental practice. Issues of power also need to be addressed, and the potentiality positive and functional aspects of conflict in organisations recognised.19

In the wider NHS, a greater involvement of doctors in managerial decisions is seen as an essential mechanism to effect real improvements in productivity and quality of care within the system.22 This reflects a global move towards greater clinical involvement in the management and strategic delivery of services which extends beyond a mainly representative model – where clinicians are like a 'Greek chorus' – commenting on what is going on on-stage, without really taking part in the play.23 In the US, where there are similar debates about the encroachment of managerial influence on the collective and individual autonomy of the medical profession,1 a great deal of autonomy is retained by individual practitioners, but there the main source of leverage which acts to preserve and qualify this autonomy, is rooted in clinicians' local membership of their professional association.2

Current notions of the type of medical engagement necessary to optimise performance involves a model of greater distributed leadership that is, many dentists at all levels engaged in priority setting and decision making, particularly around models of care, quality and safety. This is somewhat at odds with the principle of professional restratification, where rank and file practitioners become subject to the power of medical elites who exercise considerable technical, administrative and cultural authority.24 Friedson describes restratification as 'professionalism reborn in a hierarchical form', and a means of retaining professional authority over the content and provision of care - although this brings with it an inherent danger; that an essential ingredient of homogeneity among the profession is compromised,2 leading to disaffection among the 'rank and file'. A greater degree of distributed leadership helps to resolve some of these tensions.

While there is a need for a greater degree of clinical leadership in dentistry, our study indicates that notions of what this constitutes, varies significantly between the policy outlined and the thoughts of the 'rank and file' practitioner. This is by no means a tension experienced only in dentistry: Clark23 suggests that 'clinical engagement' is often talked about in terms of what 'someone else should do' – when managers talk about physician engagement they are generally speaking in code for what they would like clinicians to do but cannot get them to do; but when clinicians speak about engagement, they are speaking in code for what they 'give that is not appreciated, valued or supported by the administration'. Clinical engagement is suggested as probably more important than clinical leadership itself in terms of optimising service quality and efficiency.23 Our paper adds support for this view, and identifies new challenges for the new dental commissioning structure - to recognise ways to foster greater links between dental practitioners as well as resolving the dichotomy between the macro and micro-level views of dental service delivery.

Commentary

This is a timely paper coming as it does when local dental networks are just finding their feet and voice, and at a time when it is announced that £6 billion of health and social care spending in Greater Manchester will be overseen by a devolved body to manage and allocate priorities for spending in specialised services, social care and public health from April 2016. This paper is based on 333 free text narrative responses to a questionnaire sent to 925 practitioners. The paper concludes that whilst clinical leadership is exulted as the new driver for change, it is clinical engagement by practitioners with the commissioning process that will matter more in the coming years.

What is troubling is that the 'rank and file' GDPs churning through the UDA contract in England fear a number of things. They fear that local commissioners and the Government have created an ambiguous system that operates to trip them up at the micro-level of treating patients and interpreting the contract. This cynical paranoia is well founded in the complexity of NHS contract regulations about mixing NHS and private treatment and when to claim for certain types of treatment, such as urgent treatment. They fear that commissioners have become more disconnected from dentists. Further reorganisation of local area teams, limited access to high quality dental advice and overworked, under-resourced contract mangers will only make this worse. The self-selected GDPs who voiced their concern about the contract expressed a fear of injustice about the current NHS contract, wondering about the unfairness of it, how their colleagues were exploiting the system and leaving other dentists to pick up the high needs patients who are not well served by the system.

These GDPs also decried the 'elite' dentists; whose cosy relationship with commissioners they perceived gave them an unfair advantage in tendering awards and scrutiny of their delivery of their contracts.

The authors accept this may not be a representative or generalisable sentiment across the country but it certainly undermines professional relationships. The prospect of internecine warfare between general dental practitioners may not be on the cards but unless dentists involve themselves with their LDC's, the BDA through their representative committees such as the General Dental Practitioners Committee (GDPC) and in their local dental network, clinical commissioning will be a one sided affair. And that side, the commissioners' side are likely to have all the power especially if the Greater Manchester model is rolled out in stark contrast to the national commissioning we all thought we would get in April 2013 when NHS England came into being.

Len D'Cruz General Dental Practitioner Dento-legal advisor Dental Protection Ltd

Author questions and answers

1. Why did you undertake this research?

As part of an NIHR funded study on NHS dental practice contracting we undertook a postal questionnaire to investigate practitioners' relationships and dealings with commissioners, their involvement with professional networks and their interpretation of the current NHS dental contract.1 We received so many detailed and lengthy responses in the free text section of the questionnaire that we felt this merited an in-depth analysis. We decided that these narratives were suited to a discourse analysis which focussed on identifying common understandings and ways of acting expressed in naturalistic forms of communication. Studying the unsolicited nature of the comments in this way, allowed us to uncover practitioners' social norms, their construction of their personal and group identities, and the way in which their social and political interactions tend to be played out. Because the context of the questionnaire was NHS commissioning and contracting, our data gave an insight into a dental practice world – revealing deep tensions between clinical and small business activity and the managerial and policy level where decisions are made.

2. What would you like to do next in this area to follow on from this work?

NHS dental commissioning has been recently restructured, with the degree of clinical influence on commissioning decisions renegotiated. With local professional networks emerging as a key player in commissioning arrangements, studying whether these clinical leaders can bridge the separation between micro-level and macro-level concerns will be important – or whether 'rank and file practitioners' remain discontented and cynical because the nature of the dental market means that truly clinical leaders will always be conflicted on account of vested interests.

References

Fitzgerald L, Ferlie E . Professionals: back to the future? Hum Relat 2000; 53: 713–739.

Freidson E . Profession of medicine: a study of the sociology of applied knowledge. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1988.

Parsons T . The social system. London: Tavistock Publications, 1951.

Harris R, Mosedale S, Garner J, Perkins E . What factors influence the use of contracts in the context of NHS dental practice – a systematic review of theory and logic model. Soc Sci Med 2014; 108: 54–59.

Ferlie E . The creation and evolution of quasi-markets in the public sector: some early evidence from the NHS. Policy Polit 1994; 22: 105–112.

Department of Health. Health reform in England: update and commissioning framework. 2006. Online information available at http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20080814090418/dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/DH_4137226 (accessed March 2015).

Smith J, Lewis R, Harrison T . Making commissioning effective in the reformed NHS in England. London: Health Policy Forum, 2006. Online information available at http://www.birmingham.ac.uk/Documents/college-social-sciences/social-policy/HSMC/publications/2006/Making-Commissioning-effective.pdf (accessed March 2015).

Steele J for the Department of Health. NHS dental services in England. An independent review. 2009. Online information available at http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20130107105354/http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/DH_101137 (accessed March 2015).

NHS Commissioning Board. Securing excellence in commissioning NHS dental services. 2013. Online information available at http://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2013/02/commissioning-dental.pdf (accessed March 2015).

Harris R, Holt R . Interacting logics in general dental practice. Social Sci Med 2013; 94: 63–70.

Harris R, Brown S, Holt R, Perkins E . Do institutional logics predict dental chair-side opportunism? Social Sci Med 2014; 122: 81–89.

O'Cathain A, Thomas K J . 'Any other comments?' Open questions on questionnaires – a bane or a bonus to research? BMC Med Res Methodol 2004; 4: 25.

Hammersley M . On the foundations of critical discourse analysis. Lang Commun 1997; 17: 237–248.

Potter J . Discourse analysis and discursive psychology. In Cooper H (ed) APA handbook of research methods in psychology. Volume 2: research designs - quantitative, qualitative, neuropsychological and biological. Washington: American Psychological Association Press, 2012.

Maguire S, Hardy C . Organising processes and the construction of risk: a discursive approach. Acad Manage J 2013; 56: 231–255.

Starks H . Choose your method: a comparison of phenomenology, discourse analysis, and grounded theory. Qual Health Res 2007; 17: 1372–1380.

Burck C . Comparing qualitative research methodologies for systematic research: the use of grounded theory, discourse analysis and narrative analysis. J Fam Ther 2005; 27: 237–262.

Thorne M L . Colonizing the new world of NHS management: the shifting power of professionals Health Ser Manag Res 2002; 15: 14–26.

Edmonstone J . Clinical leadership: the elephant in the room. Int J Health Plann Manage 2009; 24: 290–305.

Friedson E . The reorganisation of the medical profession. Med Care Res Rev 1985; 42: 11–35.

Frankford D M, Konrad T R . Responsive medical professionalism: integrating education, practice and community in a market-driven era. Acad Med 1998; 73: 138–144.

Department of Health. High quality care for all: NHS next stage review final report. 2008. Online information available at https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/228836/7432.pdf (accessed March 2015).

Clark J . Medical leadership and engagement: no longer an optional extra. J Health Organ Manag 2012; 26: 437–443.

Mahmood K . Clinical governance and professional restratification in general practice. J Manag Med 2001; 15: 242–252.

Harris R, Brown S, Holt R, Perkins E . Do institutional logics predict interpretation of contract rules at the dental chair-side? Soc Sci Med 2014; 122: 81–89.

Acknowledgements

HS&DR Funding Acknowledgement: This project was funded by the National Institute for Health Research Health Services and Delivery Research Programme (project number 09/1801/1055).

Department of Health Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed therein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the HS&DR Programme, NIHR, NHS or the Department of Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed Paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Harris, R., Garner, J. & Perkins, E. A discourse of disconnection – challenges to clinical engagement and collaborative dental commissioning. Br Dent J 218, 393–397 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2015.246

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2015.246

This article is cited by

-

Collaborative leadership with a focus on stakeholder identification and engagement and ethical leadership: a dental perspective

British Dental Journal (2021)

-

The relationship between professional and commercial obligations in dentistry: a scoping review

British Dental Journal (2020)