Key Points

-

Highlights the pressures facing general dental practitioners' engagement with CPD.

-

Questions the effectiveness and quality assurance processes of CPD.

-

Emphasises some of the potential problems with translational clinical research.

Abstract

Objectives To explore general dental practitioners' opinions about continuing professional development (CPD) and potential barriers to translating research findings into clinical dental practice.

Design Qualitative focus group and interviews.

Subjects, setting and methods Four semi-structured interviews and a single focus group were conducted with 11 general dental practitioners in North East England.

Outcome measure Transcripts were analysed using the constant comparative method to identify emergent themes.

Results The key theme for practitioners was a need to interact with colleagues in order to make informed decisions on a range of clinical issues. For some forms of continuing professional development the value for money and subsequent impact upon clinical practice was limited. There were significant practice pressures that constrained the ability of practitioners to participate in certain educational activities. The relevance of some research findings and the formats used for their dissemination were often identified as barriers to their implementation in general dental practice.

Conclusions There are a number of potential barriers that exist in general dental practice to the uptake and implementation of translational research. CPD plays a pivotal role in this process and if new methods of CPD are to be developed consideration should be given to include elements of structured content and peer review that engages practitioners in a way that promotes implementation of contemporary research findings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Researchers are encouraged by their institutions to publish in specialist journals with high impact factors.1 For universities and other institutions they are an esteem indicator that relates to frequency by which articles are subsequently cited by other researchers.2 Impact factors do not, however, measure changes in clinical practice, arguably a truer impact, brought about by the results of publication. Clinical impact is difficult to assess, unless the evidence is widely adopted or incorporated into national or international clinical guidelines but despite their existence, subsequent implementation into practice is not always a linear process.3 Selective publication in specialist journals risks disseminating the results of clinically relevant data to a niche audience that, by its very nature, is not based in primary care. This strategy for dissemination risks isolating research from the environment where the vast majority of dental service is delivered.4 An understanding of how dental practitioners engage with continuing education and how researchers should engage with practitioners is critical to bridging the divide between research and practice. If ignored and research cannot easily be translated into clinical practice, this divide is likely to widen.5

Accessing publications can form a component of dentists' continuing professional development (CPD) but since its introduction in 2003 as a legal requirement in the UK, a number of competing sources of continuing education have developed.6 The variation in quality of CPD with the potential consequences impacting upon patient safety has been criticised.7 The focus of this study was therefore to explore some of the difficulties that general dental practitioners have in selecting reliable research evidence to support an evidence-based clinical practice. It looked to examine which methods of continuing education and dissemination of research were perceived to be the most effective. The results should inform clinical researchers, government organisations, regulators and manufacturers about how best to engage with dental practitioners, particularly in presenting and disseminating research findings and impact upon clinical practice.

Objective

The objective was to explore the effectiveness of CPD among a sample of general dental practitioners and identify barriers to adopting new clinical evidence into practice.

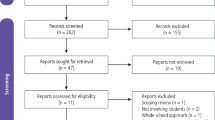

Methods

A purposive sampling strategy was used to obtain a varied sample of general dental practitioners working in the North East of England.8 The sample was stratified in order to include male and female practitioners and the number of years of experience: less than 2 years; 2–10 years; and more than 10 years post-qualification.

The study was risk assessed and insured through Newcastle University after the protocol had been externally reviewed by the research and development department at NHS North of Tyne. It was not subject to NHS ethical review process as patients were not involved in the design or conduct of the research.

One member of the research team (SS) conducted the face-to-face interviews and facilitated the focus group. Interviews took place in participants' workplaces but the focus group meeting was held at Newcastle University. In all settings, only the interviewer and participant(s) were present.

The semi-structured interviews were held first and followed an initial topic guide drawn from an earlier review of the existing scientific literature. It was anticipated that the topic guide would be modified in light of the responses received from participants so that emergent themes could be explored in greater depth as the interviews progressed.

The semi-structured interviews and the focus group discussion were audio-recorded before being professionally transcribed verbatim. The semi-structured interviews lasted between 27 and 53 minutes and the focus group recording lasted 104 minutes. Unique identifier codes were used on the transcripts instead of participants' names to maintain anonymity.

The data were manually analysed using the constant comparative method.9 Each transcript was therefore coded and its data assessed in turn in order to identify the pertinent issues and to guide the direction of the next interview or focus group. Following an initial analysis of the anonymised transcripts (SS), another member of the research team (RH) undertook independent analysis of the unmarked transcripts. Both researchers then met to agree a thematic framework.

Results

Four semi-structured interviews and a focus group were held with participants (Table 1). The sample included principal and associate general dental practitioners with between 1 and 28 years' experience of practising dentistry. Four themes emerged from analysis of the data: networking; postgraduate education; practice pressures and the relevance of research findings to general dental practice (Table 2).

Networking

Participants placed a great deal of importance upon having discussions and engaging with colleagues when considering a range of topics including treatment options, new materials, procedures and their own CPD. Although this interaction occurred in a number of different ways, informal discussion with colleagues during the working day (particularly around lunch breaks) occurred most commonly. Indeed, the value and benefits derived from these conversations (described by one dentist below as a form of 'peer review') were perceived as an integral component of everyday general dental practice and a necessary precursor to implementing change.

'Before we make any changes the first thing I would do would be to seek peer review, so chat to other dentists... peer review is probably the most important non-verifiable stuff'. (Principal, ID3)

Participants discussed how they held some practitioners' opinions in higher esteem as a consequence of their experience of working in general dental practice. Clinical experience was deemed to be a key factor in practitioners' abilities to distinguish the usefulness of new information and its application to clinical dental practice. Similarly, experienced practitioners who conducted a significant amount of certain types of treatment were seen to be influential.

A potential barrier to implementing clinical techniques in practice was when subjects and clinical interventions were viewed as being 'academic'. Based upon the personal experiences of participants, discussion emphasised the divisions that can sometimes occur between practitioners operating in different practising environments. In these situations, the professional background of the clinician providing the advice was an important consideration for primary care-based clinicians.

'If one [dentist] is in the hospital and one in practice, they'll find it difficult to relate to each other... especially on cases and treatment plans. The barrier isn't the people; it's the environment in which they work'. (Principal, ID8)

Practitioners described two contrasting preferences for the types of person they would seek for advice or information. Some participants favoured a 'true peer' who was typically described as a conscientious clinician undertaking a similar scope of practice with whom they could easily relate. Other participants, however, favoured identifying an 'expert peer' who they perceived to be an opinion leader even if they were associated with a different practising demographic. Typically, expert peers were described as being active in undergraduate and postgraduate education or they were experienced practitioners with private practice commitments.

Engaging and talking with colleagues acted as means to process and triangulate the information received at postgraduate courses and conferences. This was deemed an important activity as a consequence of the potential for bias at conferences and other CPD events where presenters may favour specific techniques or materials.

'Sometimes people present all the positives of something but don't give you the pitfalls'. (Associate, ID2)

Practitioners felt a need to informally appraise the relevance of the data and techniques presented to their own practice of dentistry through informal conversation with colleagues. As a result, CPD formats that encouraged networking provided welcome opportunities for discussion.

'[In] the ones with really long coffee and lunch breaks you learn just as much talking to your colleagues in the break as the person standing at the screen'. (Associate, ID1)

Participants identified a number of perceived risks in not participating in peer review with colleagues. General dental practice was described as potentially isolating particularly if practitioners had been working in the same practice for a number of years. Opportunities to develop informal links with clinicians from other practices were thought to assist in preventing the development of complacency with respect to current practice. In particular, those involved in the training of foundation dentists cited the benefits of engaging in discussion with newly-qualified graduates and added that this also provided an incentive to keep up to date and maintain their own knowledge. The time pressure associated with general dental practice was also acknowledged as a factor that limited the opportunities for networking and peer review.

Postgraduate education

The variety of formats currently available for clinicians to access CPD subjects was viewed positively by participants. While the majority of postgraduate courses and conferences incurred expense for practitioners in both time and financial terms, it was the perceived value of the course to them as clinicians (and not necessarily the cost) that was a key factor in determining whether they would attend.

'I'm sufficiently self-aware to recognise that after three o'clock on the first day I'm not taking any more in and so I'd have a day where it was pointless me being there'. (Associate, ID1)

'Two years ago... I probably learnt three or four things and it was £600... I decided that it wasn't a great use of money'. (Associate, ID2)

Like many other educational formats available, attendance at conferences provided a number of opportunities for practitioners to gain the required number of hours of CPD required by the regulator (General Dental Council) to remain as a registrant.6 Participants in this study identified two types of conference: those primarily aimed at generalists (for example, the British Dental Association annual conference) and those more relevant to specialists and academics (for example, the British Society of Periodontology Scientific Meeting). The latter category was not perceived as being so relevant to general dental practitioners and this format was not therefore a high priority for attendance. General conferences were occasionally criticised for lacking focus and adopting a commercial bias towards marketing and cosmetic dentistry. Consequently, these conferences were felt to be more relevant to practice owners and development of 'the business of dentistry' rather than improving clinical practice. While the reputation and experience of the presenter was an important consideration, the value for money of high profile speakers with national and international reputations was questioned. The need for practitioners to regularly review their personal development plan (PDP) was agreed to be an area of good practice to avoid CPD becoming a tick box exercise simply to fulfil regulatory requirements. PDPs were used to aid decision-making, which assisted practitioners in their selection of appropriate courses from the plethora of options available.

'The increase in volume of postgraduate course and providers has led to difficulty in deciding which courses would be worthwhile attending... [it] has changed so much since I qualified, there has been an explosion'. (Principal, ID11)

One example of the significant expansion affecting CPD was thought to be the number of formally taught postgraduate courses leading to qualifications such as MSc or MClinDent. These programmes typically involved a range of learning styles providing a structure to CPD and possibly longer-term career benefits. While many of these courses were reported to attract high financial costs, several participants perceived that these programmes were directed towards younger practitioners and that they formed part of an emerging career structure in general dental practice.

'BDS isn't enough anymore, you have to continue doing exams to stay one step ahead of the competition'. (Associate, ID5)

Short, 'hands-on', clinically-oriented courses were discussed and although the perceived benefits to learning were often highly valued, others discussed how these experiences had not always provided added value to their personal development.

'You were asked to prepare a cavity and fill it with this new material, when in effect all I was doing was what I do 100 times a day... it didn't improve my ability to do the task.' (Associate, ID3)

Live clinical demonstrations allowed clinicians to make direct comparisons and appraise their own techniques, but where this educational format was not possible, recorded and edited video was thought to provide the next best alternative. Participants preferred hands-on teaching elements to be small and informal to allow the presenter to interact with colleagues and provide relevant feedback on their work.

Most practitioners recruited to this study regularly reported accessing online verifiable CPD. Younger practitioners appeared to be more accepting and engaged with this method of learning, while older practitioners preferred interaction with colleagues and the opportunity for peer review. In this small study sample, the journals most frequently used to access verifiable CPD were Dental Update and the British Dental Journal. Several other online providers were also accessed by participants (for example, Dentaljuce and the Dental Channel). These websites also typically required a subscription or annual fee and often a strong incentive to engage with specific research papers was the fact that subsequent questions would provide the desired verifiable CPD hours required as a condition of registration with the General Dental Council (GDC). Online learning was often reported to be time efficient and cost-effective for many practitioners, however, the format was also described as being 'soul destroying' by one practitioner who explained how this teaching often failed to promote changes to either behaviour or practice. A relatively new method of online learning in dentistry is the increasing use of webinars, which typically allow users to communicate with the speaker over the Internet. Webinars were perceived to be a 'safe' environment in that participants felt comfortable to ask questions either verbally or through typed messages.

Practice pressures

Participants viewed general dental practice as a busy, high-pressured environment with the single greatest pressure relating to a shortage of time in which to attend formal teaching events. Consequently, some practitioners did not view their attendance at postgraduate courses during the working week as a feasible option, especially in light of NHS contractual obligations and their associated targets for service delivery.

Participants discussed a number of clinically-oriented CPD courses including those that endorsed the use of new and/or novel dental materials. A potential barrier to using new dental materials in primary care, however, was often thought to relate to the practice principal in their role as a 'gatekeeper' in the management of resources. If a practice owner considered the financial cost of a material to be prohibitively expensive or non-essential then effectively the principal could act as a potential barrier. While some associates were prepared to purchase these materials personally, others were not, and there was the potential for conflict:

'I wouldn't like associates to all be having different materials as you want everyone using the same. Some associates do buy things themselves but it causes problems with other associates saying they want to use it as well but don't want to pay for it'. (Principal, ID9)

Private practice was considered to offer more flexibility in the use of new dental materials as any increase in financial costs could more easily be encompassed within private charges. Conversely, many of the new dental materials currently available were often perceived as being beyond the reach of NHS primary care dentistry. Practice visits from manufacturer's representatives were generally thought to be useful in raising practitioners' awareness of new products. Some participants cited negative opinions relating to the representatives' limited knowledge of the handling properties of new materials and their clinical application. Others reported being aware of who the more knowledgeable representatives were, but despite this many remained sceptical of their opinions because they were believed to be paid on commission.

Time constraints were reported as a barrier to conducting clinical audit during surgery hours; however, those practitioners working under an NHS contract are obligated to participate in such activity. A widely-held perception was that practitioners working in salaried and hospital dental services benefited from more flexibility during normal working hours and that a significant disadvantage for primary care-based NHS practitioners was the need to maintain productivity and achieve contractual (UDA) targets.

In their daily clinical work, practitioners reported implementing a number of national guidelines including those published by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), Cochrane Collaboration and the Department of Health. Several practitioners were critical of these guidelines for being difficult to interpret (for example, Cochrane) or because they relied upon expert opinion rather than other forms of scientific evidence (for example, NICE).

'I find the Cochrane things very useful, obviously they put a huge amount of work into it but it can be quite complicated to understand'. (Principal, ID3)

In the latter case, practitioners frequently reported relying upon their own expertise and experience when deciding the relevance of the guideline to their clinical practice.

Relevance of research

This theme related to the ability of practitioners to access, interpret and apply research findings to their clinical practice. Discussion initially focused upon concerns for some practitioners with respect to their ability to interpret the evidence:

'There wasn't much exposure to research papers while I was at University... it was only when I began to do my own postgraduate training I learnt how to interpret them'. (Principal, ID3)

A number of dental journals were used as examples by participants during the discussion about research findings. The scientific publications most frequently identified and read by participants were the British Dental Journal and Dental Update. Other publications (for example, Dentistry and Dental Tribune) provided more of a magazine-style, general news update on current dental issues. Collectively, these publications were thought to provide a good source of CPD for practitioners. The format and content of some publications (for example, Dental Update) was well-liked by participants for the straightforward and clear format in which relevant, practice-focused information was presented. Consequently, these articles were deemed to be more relevant to primary care dentistry as the illustrated clinical application of techniques and materials was generally preferred over the presentation of scientific charts and diagrams, which could often prove more challenging to interpret.

Accessing the range of scientific dental journals available was difficult for practitioners unless they personally subscribed or held an affiliation to a dental teaching hospital or university library. A number of additional dental journals were identified by participants in relation to paediatric dentistry and periodontology, however, these publications were also criticised for often being of limited relevance to primary dental care practitioners. These 'specialist' academic journals were perceived to be more relevant to academic and salaried dental service roles.

Discussion

Clinical researchers face a challenge in ensuring that the final steps of translational research are successful and knowledge is transferred from basic science research through controlled clinical trials and delivered into practice. The results suggest that this must be an active process, not solely involving publication in specialist journals or at society conferences. Researchers should be aware of the potential shortcomings of niche publications and consider alternative routes by which to disseminate their findings. This may include more active wider participation in providing CPD and exploring novel routes of communication and dissemination with which primary care practitioners want to engage. Academic and hospital-based practitioners should be engaged with the delivery and commissioning process of CPD programmes. While networking with peers is positive and should continue, input from other practitioners, academics and specialists would enrich and provide depth to discussions. Perhaps there should be a more robust accreditation process for CPD providers. The GDC are clear in their mandate that they do not approve CPD activity but devolve all responsibility for collecting CPD to the dental professional.10 'Quality' therefore remains difficult to judge and the question remains whether hours are the most appropriate method of continued competence and if these are indicative of continued fitness to practice.

Some of the perceived barriers lie in the environment in which clinical research is conducted and its applicability to primary care. Researchers must be mindful of this in the planning and design of research projects and, where possible, include primary care practitioners as key stakeholders and partners with academics to design and conduct studies that answer fundamental research questions that ultimately result in benefits for patients. Fully embracing primary care dentistry in the conduct of large, multicentre studies is not without its risks and costs, but it is essential to provide a true representative evidence base for developing new, patient-centred treatment strategies.

Clearly different working arrangements and practising demographics have the potential to influence behaviour. The results highlight a number of pressures in primary care that encourage the status quo. Not all of these lie within the control of the individual practitioner but are subject to the pressures of working for and with others, often within much larger organisations and with the added constraints of professional regulation and contractual obligations.

Limitations

Our findings are based upon a small purposive sample of general dental practitioners working in one region in England, yet although the study used a small sample size the responses of participants were relatively homogenous, which meant that data saturation occurred quickly.

It is not possible to generalise our findings to the wider dental workforce across England. Similarly, we do not know whether other dental professionals working in the dental team would differ significantly in their opinions. Further work could explore any similarities or differences voiced by these professional groups.

An alternative approach to elicit responses may have been to have undertaken a postal questionnaire survey. However, this method has several disadvantages including limitations on the richness of the data collected using questionnaires, the potential for poor response and the difficulty for researchers to probe respondents further on their written responses.11,12

Conclusion

There are a number of potential barriers that exist in general dental practice to the uptake and implementation of translational research. CPD plays a pivotal role in this process and if new methods of CPD are to be developed, consideration should be given in their inception to include elements of structured content and peer review that engages practitioners in a way that promotes implementation of contemporary research findings.

References

Thomson-Reuters. ISI Web of Knowledge journal citation reports. Thomson-Reuters, 2012.

Lavis J, Ross S, McLeod C, Gildiner A . Measuring the impact of health research. J Health Serv Res Policy 2003; 8: 165–170.

Grol R, Grimshaw J . From best evidence to best practice: effective implementation of change in patients' care. Lancet 2003; 362: 1225–1230.

Department of Health, British Association for the Study of Community Dentistry. Delivering better oral health: an evidence-based toolkit for prevention. London: DH, 2009.

Bero L A, Grilli R, Grimshaw J M, Harvey E, Oxman A D, Thomson M A . Closing the gap between research and practice: an overview of systematic reviews of interventions to promote the implementation of research findings. BMJ 1998; 317: 465–468.

General Dental Council. Continuing professional development for dentists. London: GDC, 2012.

General Dental Council. Make wise CPD choices. GDC Gazette 2013; 7–8.

Ritchie J, Lewis J, Elam G . Designing and selecting samples. In Ritchie J, Lewis J (eds) Qualitative research practice - a Guide for social science students and researchers. pp 77–86. London: Sage, 2003.

Glaser B G . The constant comparative method of qualitative analysis. Soc Probl 1965; 12: 436–445.

General Dental Council. Continuing professional development for dental professionals. London: GDC, 2013.

McColl E, Jacoby A, Thomas L et al. Design and use of questionnaires: a review of best practice applicable to surveys of health service staff and patients. Health Technol Assess 2001; 5: 1–256.

Edwards P, Roberts I, Clarke M, DiGuiseppi C, Pratap S, Wentz R . Increasing response rates to postal questionnaires: systematic review. BMJ 2002; 324: 1183.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the general dental practitioners who participated in this study. Conflicts of interest and sources of funding: This was an investigator's self-funded study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed Paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Stone, S., Holmes, R., Heasman, P. et al. Continuing professional development and application of knowledge from research findings: a qualitative study of general dental practitioners. Br Dent J 216, E23 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2014.451

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2014.451