Key Points

-

Raises awareness of the importance of primary care dentists determining a patient's risk of bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw (BRONJ) before bone-impacting dental treatments.

-

Provides evidence suggesting that dentists need more support to revise and update their practice relating to BRONJ to ensure it is consistent with best practice recommendations.

Abstract

Background In April 2011 the Scottish Dental Clinical Effectiveness Programme published the Oral health management of patients prescribed bisphosphonates guidance document. The aims of this study were to examine whether dentists' practice and beliefs changed after guidance publication to determine whether a knowledge translation intervention was required, and to inform its development.

Methods Three postal surveys sent to three independent, random samples of dentists throughout Scotland pre- and post-guidance publication. The questionnaire, framed using the theoretical domains framework (TDF), assessed current practice and beliefs relating to recommended management of patients on bisphosphonates.

Results The results (N = 420) suggest that any significant impact the guidance may have had on the recommended management of patients on bisphosphonates by primary care dentists, had reached its peak ten months post publication. A more positive attitude, greater perceived ability, and greater motivation were all associated with significantly more performing of all recommended behaviours at every time point.

Conclusions Prior to this study, there was little available information about how patients on bisphosphonates were being managed in primary dental care, or what beliefs may be influencing management decisions. This study was able to identify levels of compliance pre- and post-guidance publication and determine that further intervention was necessary to enable sustained uptake of recommendations. Using the TDF to identify beliefs associated with best practice made it possible to suggest theoretically informed strategies for service improvement. The next step is to test the intervention(s) in a randomised controlled trial.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Bisphosphonates are a class of drugs used to delay the onset and slow the progression of bone-impacting diseases and conditions, as well as to moderate bone-related treatment complications. Bisphosphonates can significantly improve quality of life by reducing bone pain and the risk of bone fractures. However, bisphosphonates accumulate at sites of high bone turnover, like the jaw. This accumulation can reduce bone blood supply to these areas, which could lead to osteonecrosis, particularly if that site is injured.

Dentists are seeing an ever-increasing number of patients on bisphosphonates as these drugs are now more commonly prescribed to prevent and manage a variety of conditions, including osteoporosis. In April 2011, the Scottish Dental Clinical Effectiveness Programme (SDCEP) published guidance on the oral health management of patients prescribed bisphosphonates.1 The guidance was designed to reduce uncertainty about whether and when a patient on bisphosphonates should receive dental treatment in primary care so as to reduce the risk of bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw (BRONJ). The guidance was prompted by stakeholder concern that patients on bisphosphonates were experiencing unnecessary delays in receiving urgently needed dental treatment because they were being referred to oral surgery/oral maxillofacial surgery specialists instead of being treated more appropriately in primary care. There was also the possibility that patients who should be referred to specialists for some dental treatments, were being treated inappropriately in primary care. The SDCEP guidance includes advice about how primary care dentists can assess BRONJ risk, and outlines best practice recommendations for general and risk-specific treatment options for patients on bisphosphonates, including when to ask advice from, or refer to, specialists before carrying out dental treatment in primary care.

Nevertheless, it is well-documented that the publication of guidance documents may not be enough to result in the translation of best practice recommendations into clinical practice.2,3,4,5 To investigate this issue in dentistry, the education and training body for NHS Scotland (NES) established the Translation Research in a Dental Setting programme (TRiaDS) to work in partnership with SDCEP.6 This paper describes a TRiaDS study investigating the translation of the SDCEP guidance on managing patients prescribed bisphosphonates into Scottish primary care dental practice. The three aims of this study were:

-

1

Examine the primary dental care management of patients on bisphosphonates before and after guidance publication. The objective was to determine if further intervention was required to encourage the uptake of this guidance's recommendations into clinical practice.

-

2

To identify dentists' beliefs associated with SDCEP recommended management of patients prescribed bisphosphonates and examine these beliefs before and after guidance publication. The objective was to inform intervention design by identifying specific beliefs that may be influencing compliance with recommended management behaviours.

-

3

To identify possible strategies to improve compliance via changing target beliefs, should further intervention be required.

Method

Design

This study includes a series of three postal surveys. The SDCEP bisphosphonates guidance was published in April 2011. In February 2011, 2012 and 2013 an identical questionnaire was mailed to three independent, random samples of dentists throughout Scotland. The questionnaire assessed current practice and beliefs relating to the management of patients on bisphosphonates.

Measures

Current practice

Using the SDCEP guidance document as a guide, study researchers and stakeholders (members of the SDCEP guidance working group, research fellows in oral healthcare, a health psychologist, and academic dentists involved in teaching and primary care research) identified 16 key behaviours that should be included when assessing current practice for managing patients prescribed bisphosphonates (Table 1).

Eight of these key behaviours were relevant for managing all patients prescribed bisphosphonates. To further an understanding of where uptake issues may lie, these eight behaviours were grouped into four management categories (record, assess, prevent, monitor). This was also a way of discriminating between behaviours that the guidance recommends (in categories record, assess, monitor) and historically established behaviours it suggests omitting from current practice because of the lack of supporting evidence (all in the 'prevent' category: ie not prescribing chlorhexidine, not prescribing antibiotics, not arranging drug holidays).

The SDCEP guidance supports risk-based management for the other eight behaviours, depending on whether patients have a lower BRONJ risk (for example, taking (or starting) bisphosphonates to manage osteoporosis but are otherwise healthy), or higher BRONJ risk (for example, taking (or starting) bisphosphonates to manage malignant conditions). Data on managing via these eight behaviours were grouped within the two risk categories (see Table 1).

Dentists were asked to rate how often they were implementing each of the 16 behaviours using a five-point scale (never, rarely, sometimes, usually, always). Every response of 'usually/always' following recommended management was given a score = 1, all other responses were given a score = 0. Current practice, in terms of compliance with guidance recommendations (Table 1), was calculated from the frequency scores (that is, percentage of scores = 1). The mean of the summed frequency scores for the collated behaviours within each management category (record, assess, prevent, monitor, manage lower BRONJ risk and manage higher BRONJ risk) were used to calculate current practice scores for the ANOVA (Table 1), correlation (Table 3), and regression (Table 4) analyses. The results are presented so that higher scores reflect better practice.

Beliefs

This study used the theoretical domains framework (TDF) to identify beliefs associated with the management of patients prescribed bisphosphonates.7 The TDF synthesises 128 variables from 33 theoretical models into 12 discrete domains (namely, knowledge, skills, professional identity, beliefs about capabilities, beliefs about consequences, goals/motivation/intention, memory, environmental context and resources, social and professional influence, emotion, behavioural regulation, nature of the behaviour). It has protocols for choosing the most relevant domain(s) to apply to a behaviour, for assessing domains and associated beliefs, and for linking beliefs with behaviour change strategies that can be incorporated into intervention design.8,9,10,11,12 This makes it a pragmatic tool for comprehensively exploring beliefs associated with clinician decision-making and for enabling non-theorists to provide a theoretical underpinning to intervention design, as supported by the UK Medical Research Council (MRC).13 The TDF has been successfully applied to a variety of clinical behaviours including blood transfusion, prescribing and hand washing.14,15,16

Following the TDF protocols, study researchers and stakeholders identified beliefs within TDF domains that are likely to be salient to managing patients on bisphosphonates in primary care. These were: attitude (from the TDF domain 'beliefs about consequences'); perceived ability (from the TDF domain 'beliefs about capabilities'); and motivation (from the TDF domain 'goals/motivation/intention'). In the postal questionnaire, to assess attitude dentists were asked if each behaviour was important for managing patients on bisphosphonates in the guidance-recommended way, was appropriate to perform in primary care, and if it was something they would rather refer to a specialist (an oral surgeon or oral maxillofacial surgeon) to perform. To assess perceived ability, dentists were asked how difficult they thought each behaviour was to carry out. To assess motivation, dentists were asked how motivated they were to perform each behaviour. All belief items used the same five-point response scale ('strongly disagree' to 'strongly agree').

Separate totals (mean of summed responses) were created for attitude, ability and motivation for each management category (record, assess, prevent, monitor, lower BRONJ risk and higher BRONJ risk). Variables were scored so that higher scores reflect stronger beliefs in support of performing the guidance-recommended behaviours.

Procedure

A total of 1,296 dentists were randomly selected across three different time points. The sample was identified from a database provided to the dental directorate in NHS Education for Scotland by the Information Services Division (ISD). This database contains the contact information of all dentists in Scotland providing primary care NHS dental services. Computer-generated random numbers were used to select dentists across Scotland.

Two months prior to the SDCEP guidance publication, an invitation letter and questionnaire were posted to 300 dentists. Ten months post publication, 595 dentists were randomly assigned to receive the letter and questionnaire via post (N = 293) or via email (N = 302). Twenty-two months post publication, 400 dentists were posted a questionnaire. All non-respondents were posted the questionnaire two weeks after each initial mailing, and then a postcard reminder after four weeks.

Statistical analysis

Statistical significance was based on two-sided tests with p = 0.05 as the criterion. Measures were tested for internal consistency using Cronbach's alpha. Changes in behaviour and beliefs over time were tested using ANOVA and Bonferonni post hoc comparison tests. The relationship between beliefs and SDCEP guidance recommended management were examined using Pearson correlations at each time point and stepwise multiple regression analyses which combined all three time point samples.

Results

Response rate and participants

Response rate for the T1 survey was 38% (114/300). The overall response rate for the T2 survey was 40% (117/293) via post; 10% (31/302) via email. At T3, the response rate was 39% (158/400). The total sample profile (N = 420) was: 62% male, average age was 43 years (ranging between 23 and 70); 49% were practice principals, 45% were practice associates and 6% were salaried; On average, they worked 8.5 sessions per week, and there were two other dentists in each practice, ranging from 1 (N = 42) to 12 (N = 1); 66% of practices (277/420) employed a dental hygienist or hygienist-therapist. ANOVA revealed no significant differences between the three independent random samples (T1, T2, T3) in any of these demographic variables. Independent t-tests also revealed no significant differences between the dentists who responded to the posted or emailed invitations at T2, and therefore these participants were treated as one sample in all analyses.

The gender and health board profile of the final sample of dentists was similar to the whole population in the ISD database. Independent surveys of general dental practitioners in Scotland have had similar postal response rates and sample profiles.17,18,19

A post hoc power analysis showed that the ANOVA analyses (examining changes over time) had power = 0.99 to detect a medium effect size (f = 0.25; F-test, ANOVA: N = 420, df = 2, with three groups), as did the regression analyses (f2 = 0.15; N = 330, three predictors: attitude, perceived ability, motivation).20

Current practice (see Table 1)

Behaviours relevant to managing all patients on bisphosphonates.

-

T1: Two months before the guidance was published: Compliance ranged from 16% (18/114) to 70% (80/114). Behaviours with lowest compliance with SDCEP guidance recommendations were: (1) record the past use of bisphosphonates; (2) not prescribing chlorhexidine mouthwash after an invasive treatment; and (3) not prescribing antibiotics after an invasive treatment.

-

T2: 10 months after the guidance was published: Compliance ranged from 25% (31/148) to 79% (111/148). Behaviours with the lowest compliance with SDCEP guidance recommendations were as T1. All behaviours showed increase compliance (were more in line with recommended management) in T2 compared to T1. Behaviours showing significantly improved compliance from T1 were: (1) record current use of bisphosphonates (15% increase in compliance: F = 4.8, p <0.01) and (2) identify BRONJ risk based on medical condition (13% increase in compliance: F = 3.7, p <0.05).

-

T3: 22 months after the guidance was published: Compliance ranged from 38% (60/158) to 80% (126/158). Behaviours with lowest compliance with SDCEP guidance recommendations were the same as at T1 and T2. There was no significant change in compliance from T2 to T3. However, significantly improved behaviours from T1 to T3 were: (1) not prescribing antibiotics after an invasive treatment (22% increase in compliance: F = 3.1, p <0.05); (2) not prescribing chlorhexidine after an invasive treatment (17% increase in compliance); (3) identify BRONJ risk based on medical condition (15% increase in compliance); and (4) record current use of bisphosphonates (14% increase in compliance).

Managing patients at lower risk of BRONJ

-

T1: Two months before guidance publication: Compliance ranged from 11% (12/114) to 99% (112/114). Behaviours with lowest compliance with SDCEP guidance recommendations were: (1) ask advice from specialist before bone-impacting treatments (11% compliance); (2) perform bone-impacting treatments (18% compliance); and (3) not ask advice from specialists before straightforward extractions (32% compliance).

-

T2: 10 months after guidance publication: Compliance ranged from 14% (18/148) to 100% (148/148). Behaviours with lowest compliance with SDCEP guidance recommendations were the same as at T1. The one behaviour which showed significant improvement from T1 to T2 was: provide oral hygiene advice (9% increase in compliance, p <0.05).

-

T3: 22 months after guidance publication: Compliance ranged from 20% (32/158) to 98% (155/158). Behaviours with lowest compliance with SDCEP guidance recommendations were as T1 and T2. There was no significant change in compliance in any behaviour from T2 to T3. However, two behaviours showed significant improvement in compliance from T1 to T3: (1) provide oral hygiene advice (8% increase in compliance: F = 7.4, p <0.001); and (2) not ask advice from specialists before straightforward extractions (19% increase in compliance: F = 4.7, p <0.01).

Managing patients at higher risk of BRONJ

-

T1: Two months before guidance publication: Compliance ranged from 47% (54/114) to 96% (109/114). Behaviours with lowest compliance with SDCEP guidance recommendations were: (1) perform straightforward extractions (47% compliance); (2) undertake remedial dental work as soon as possible (74% compliance); (3) ask advice from specialists before straightforward extractions (78% compliance); and (4) perform bone-impacting treatments (79% compliance).

-

T2: 10 months after guidance publication: Compliance ranged from 51% (75/148) to 99% (146/148). Behaviours with lowest compliance with SDCEP guidance recommendations were the same as at T1. The one behaviour which significantly improved from T1 was: undertake remedial dental work as soon as possible (13% improved compliance: F = 4.1, p <0.05).

-

T3: 22 months after guidance publication: Compliance ranged from 49% (77/158) to 100% (158/158). Behaviours with lowest compliance with SDCEP guidance recommendations were as T1 and T2. There was no significant change in compliance in any behaviour from T2 to T3. The one behaviour which showed a significant improvement in compliance from T1 to T3 was: provide oral hygiene advice (4% improved compliance: F = 3.9, p <0.05).

-

At T3, participants reported complying with guidance recommendations for an average of four (SD = 2) out of eight behaviours when managing all patients prescribed a bisphosphonate, for an average of five (SD = 1.5) of the eight behaviours relating to managing lower BRONJ risk patients, and six (SD = 1.4) of the eight behaviours relating to managing higher BRONJ risk patients. No dentist was complying with all guidance recommendations at any time point.

Beliefs and practice (Table 2)

At every time point participants had a positive attitude toward performing guidance-recommended (GR) behaviours in the record, monitor, and both of the risk-based management categories. Out of a possible score of 5, means ranged between 3.7 and 4.4. On average, participants were also highly motivated and had high perceived ability to perform these behaviours (thought they were easy to do), with means ranging between 3.6 and 4.4. Participants had a comparatively less positive attitude, were less motivated, and had lower perceived ability to perform GR behaviours in the prevent category. The means for these beliefs were consistently lowest at each time point, with perceived ability to perform prevent-category behaviours the lowest of all belief means at every time point (ranging between 2.3 and 2.5).

Ten months after the guidance was published (T2), participants were significantly more motivated than they were two months before publication (T1) to perform GR behaviours in the record (F = 7.1, p <0.001) and prevent (F = 8.3, p <0.001) categories. Participants also had a significantly more positive attitude (F = 5.4, p <0.01) toward GR management of lower risk patients. No significant change in beliefs occurred in the post publication period 10 months to 22 months (T3). However, the results presented in Table 2 show that the initial changes in beliefs (T1 to T2) supporting GR management were sustained from T1 to T3. Furthermore, some beliefs which did not significantly change in the short term (T1 to T2) did change to be significantly more in favour of GR management in the longer term (T1 to T3) that is, attitude toward recording (F = 3.8, p <0.05), attitude toward prevention (F = 7.6, p <0.001), perceived ability to record (F = 3.3, p <0.05), perceived ability to manage lower BRONJ risk patients (F = 3.1, p <0.05), and motivation for GR managing lower BRONJ risk patients (F = 8.0, p <0.001).

All beliefs which were significantly correlated with GR behaviours were entered into a series stepwise regression analyses (Tables 3 and 4). Motivation explained significant variance in recording BRONJ risk (26%) and GR managing of higher BRONJ risk patients (34%). Attitude explained significant variance in following GR behaviours in the prevent (66%), monitor (60%) and manage lower BRONJ risk (47%) categories.

Discussion

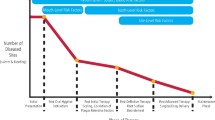

One aim of this study was to examine the primary dental care management of patients on bisphosphonates before and after guidance publication. The objective was to determine if further intervention was required to encourage the uptake of this guidance's recommendations into clinical practice. Ten months after the guidance was published (T2), all but one of the key behaviours were being performed more in line with guidance recommendations compared to reports of current practice in the survey conducted 2 months prior to publication (T1). At 22 months post publication (T3), current practice had changed very little from T2.

This suggests that most of the guidance recommendations had permeated the practice of the general population of dentists in Scotland within 10 months of its publication. However, the trend toward better practice attenuated over time. The results suggest that any significant impact the guidance may have had on the GR management of patients prescribed bisphosphonates had reached its ceiling by 10 months. This, together with noncompliance for most behaviours still occurring at 10 months and at 22 months post publication, strongly supports the need for further intervention to encourage dentists to improve their uptake of these guidance recommendations. It also adds to the general evidence that clinicians need more than the publication of guidance to improve and sustain changes in clinical practice.

The underlying message of this guidance was for primary care dentists to more often manage lower BRONJ risk patients without asking specialists for advice or referring patients. The results of this study suggest that this message was being communicated to primary care dentists in Scotland post publication. However, an unexpected generalisation effect also seems to have occurred in that fewer dentists were also asking advice or referring higher BRONJ risk patients to specialists compared to pre-guidance practice (that is, there was an decrease in compliance for managing this patient group after publication). The appearance of what may be a guidance-inspired problem affecting patients at most risk of BRONJ provides further support for an intervention.

The second aim of this study was to identify beliefs associated with GR management and examine these beliefs before and after guidance publication. The objective was to identify specific beliefs that could be targeted to influence compliance with recommended management behaviours and so inform intervention design. In order to provide a theoretical underpinning to this research, the TDF was used to identify and assess beliefs that may influence clinician decision-making relating to the management of patients on bisphosphonates. This methodology was given some validation because all beliefs identified using this process were significantly associated with all GR management categories included in these analyses (record, prevent, monitor, manage patients at higher and lower BRONJ risk). Furthermore, they acted as would be expected, with a more positive attitude, greater perceived ability, and greater motivation associated with significantly more GR management at every time point. Although a significant correlation is not evidence of a causal relationship, it is a necessary precursor of one. This study was therefore able to identify beliefs that could be targeted in an area (managing patients prescribed bisphosphonates) where there is currently little information about what may be guiding decision-making.

The final aim of this study was to identify possible strategies to improve guidance compliance, should further intervention be required. The results of the regression analyses were able to narrow the possible belief targets even further, suggesting that strategies should focus on encouraging a more positive attitude to behaviours in the prevent, monitor, and lower BRONJ risk management categories, as well as increase motivation to perform behaviours in the record and higher BRONJ Risk management categories. There are evidence-based psychological techniques that can be used to influence attitude and motivation, including providing information, persuasive statements, positive reinforcement and encouragement, goal setting and prompts, all of which can inform intervention design.21,22,23 Furthermore, taking snapshots of current practice from independent samples of dentists at different time points helped pinpoint where primary care dentists need most support to improve their uptake of GR management. All three samples showed lowest level of compliance with the same behaviours: not asking advice from specialists before bone-impacting treatments when managing patients at lower BRONJ risk; not prescribing antibiotics to prevent BRONJ after an invasive treatment; perform bone-impacting treatments when managing patients with lower BRONJ risk; not performing bone-impacting treatments when managing patients with higher BRONJ risk; and ask advice from specialists before straightforward extractions when managing patients at higher BRONJ risk.

An example of an intervention which targets beliefs and behaviours identified in this study would be to use professional media and/or send a letter to all dentists in Scotland. This would be to provide information about evidentiary and professional support for asking advice from specialists before bone-impacting treatments when managing patients at higher but not lower BRONJ risk, and to encourage dentists not to prescribe antibiotics or chlorhexidine to prevent BRONJ. Dentists might also benefit from a postcard reminder that SDCEP guidance documents are available on line, along with a prompt to check that their current practice is in line with guidance recommendations.

An issue which emerged in this study was how difficult dentists perceived it was to follow recommendations to omit behaviours from established practice (not prescribing chlorhexidine, not prescribing antibiotics, not arranging drug holidays). They were also less motivated and had a less favourable attitude toward omitting these three behaviours, compared to performing the other 13 behaviours at every time point. A possible reason for this is that the guidance reports that there is no evidence that these behaviours can prevent BRONJ, and that these behaviours do not increase BRONJ risk. It is plausible that this reflects just how concerned dentists are about taking every possible precaution to prevent BRONJ, and how reluctant they are to relinquish these behaviours in their current management arsenal. Nevertheless, 'it can't hurt' is not really an appropriate philosophy for best practice healthcare.

Although this study was adequately powered, the low response rate may cast doubts about the generalisability of these results. However, there is no indication that the randomly selected dentists in this study differed in their demographics from the total population of dentists in Scotland, nor from other dentists independently and randomly selected for other national surveys. Furthermore, the snapshot approach was a pragmatic way of identifying current practice and beliefs from a greater number of dentists from the relatively small population of dentists in Scotland. It could be argued that having three random sets of independent samples from all the GDPs in Scotland ensured that the study participants were as representative as possible. The three independent samples were certainly representative of each other. Evidence for this is the lack of significant differences between these samples in any demographic variable, including gender, age, practice role, average sessions worked per week, number of colleagues, if they had been a vocational trainer and if their practice employed a hygienist/hygienist therapist.

This study did attempt to improve response rates by including another approach to delivering the survey to this population. The T2 questionnaire was delivered by post, as well as online to two independent random samples of dentists. The hope was that this much less costly delivery method would result in a similar response rate to the postal method, and so be worth pursuing in the later follow-up. However, the online delivery had a dismal response rate and this methodology was not repeated. There was no significant difference in the demographics of the responding participants, nor did excluding the 31 dentists who did reply electronically significantly change any of the results. It is possible that using the email addresses automatically allocated by the NHS to each NHS list number, rather than any personal email account, may be the source of the problem. Any dentist not using the NHS generated email address would be completely unaware of the survey invitation.

Conclusion

Prior to this study, there was little available information about how patients on bisphosphonates were being managed in primary dental care in Scotland, or what beliefs may be mediating management decisions. This study was able to identify levels of compliance pre-and post-guidance publication for specific recommended behaviours and determine that further intervention was necessary to encourage better practice. Applying a theoretical framework to identifying and assessing beliefs which may be driving the performing of guidance recommended behaviours made it possible to suggest theoretically informed interventions based on study results. The next step is to implement the intervention(s) in a system wide, randomised controlled trial.

Although this study is set in Scotland, its subject and findings are of current relevance to all UK dentists. Bisphosphonates are now more commonly prescribed across the UK to prevent and manage more conditions, and so all dentists are going to be dealing with more patients at risk of BRONJ. Furthermore, there is an ever increasing number of guidance documents being produced. It is not appropriate to ignore the evidence showing that dentists need support to revise and update their practice following guidance publication. It is hoped that the results of this study can provide some insight when addressing these issues.

References

Scottish Dental Clinical Effectiveness Programme. Oral Health Management of Patients Prescribed Bisphosphonates. April 2011. Available online at http://www.sdcep.org.uk (accessed 1 December 2014).

Seddon M E, Marshall M N, Campbell S M, Roland M O . Systematic review of studies of quality of clinical care in general practice in the UK, Australia and New Zealand. Qual Health Care 2001; 10: 152–158.

Grimshaw J M, Thomas R E, MacLennan G et al. Effectiveness and efficiency of guideline dissemination and implementation strategies. Health Technol Assess 2004; 8: 1–84.

Grol R : Improving the quality of medical care. Building bridges among professional pride, payer profit, and patient satisfaction. JAMA 2001; 286: 2578–2585.

Bero L A, Grilli R, Grimshaw J M, Harvey E, Oxman A D, Thomson M A . Closing the gap between research and practice: an overview of systematic reviews of interventions to promote implementation of research findings by health care professionals. BMJ 1998; 317: 465–468.

Clarkson J E, Ramsay C R, Eccles M P et al. The translation research in a dental setting (TRiaDS) programme protocol. Implement Sci 2010; 5: 57.

Michie S, Johnston M, Abraham C, Lawton R, Parker D, Walker A . Making psychological theory useful for implementing evidence based practice: a consensus approach. Qual Saf Health Care 2005; 14: 26–33.

Francis J, O'Connor D, Curran J . Theories of behaviour change synthesised into a set of theoretical groupings: introducing a thematic series on the theoretical domains framework. Implement Sci 2012; 7: 35.

Cane J, O'Connor D, Michie S . Validation of the theoretical domains framework for use in behaviour change and implementation research. Implement Sci 2012; 7: 37.

Francis J J, Stockton C, Eccles M P et al. Evidence-based selection of theories for designing behaviour change interventions: using methods based on theoretical construct domains to understand clinicians' blood transfusion behaviour. Br J Health Psychol 2009; 14: 625–646.

French S D, Green SE, O'Connor D A et al. Developing theory-informed behaviour change interventions to implement evidence into practice: a systematic approach using the Theoretical Domains Framework. Implement Sci 2012; 7: 38.

Abraham C, Michie S . A taxonomy of behavior change techniques used in interventions. Health Psychol 2008; 27: 379–387.

Medical Research Council. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: new guidance. London: MRC, 2008.

Islam R, Tinmouth A T, Francis J J et al. A cross-country comparison of intensive care physicians' beliefs about their transfusion behaviour: A qualitative study using the theoretical domains framework. Implement Sci 2012; 7: 93.

Duncan E M, Francis J J, Johnston M et al. Learning curves, taking instructions, and patient safety: using a theoretical domains framework in an interview study to investigate prescribing errors among trainee doctors. Implement Sci 2012; 7: 86.

Boscart V M, Fernie G R, Lee J H, Jaglal S B : Using psychological theory to inform methods to optimize the implementation of a hand hygiene intervention. Implement Sci 2012; 7: 77.

Borrie, F, Bonetti D., Bearn D . What influences the implementation of interceptive orthodontics in primary care? Br Dent J 2014; 216: 687–691.

Glidewell, L, Thomas, R, MacLennan et al. Do incentives, reminders or reduced burden improve healthcare professional response rates in postal questionnaires?: Two randomised controlled trials. BMC Health Serv Res 2012; 12: 250.

Leavy P, Templeton A, Young L, McConnell C . Reporting of occupational exposures to blood and body fluids in the primary dental care setting in Scotland: An evaluation of curren practice and attitudes. Br Dent J 2014; 217: E7.

Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang A G, Buchner A . G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav Res Methods 2007; 39: 175–191.

Abraham C, Michie S . A taxonomy of behavior change techniques used in interventions. Health Psychol 2008; 27: 379–387.

Bonetti D, Johnston M, Pitts N B et al. Knowledge may not be the best target for strategies to influence evidence-based practice: Using psychological models to understand RCT effects. Int J Behav Med 2009; 16: 287–293.

Eccles M, Grimshaw J, Walker A, Johnston M, Pitts N . Changing the behaviour of healthcare professionals: the use of theory in promoting the uptake of research findings. J Clin Epidemiol 2005; 58: 107–112.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the TRiaDS working group, participating dentists and NES for funding this study. The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and may not be shared by others.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed Paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bonetti, D., Clarkson, J., Elouafkaoui, P. et al. Managing patients on bisphosphonates: The practice of primary care dentists before and after the publication of national guidance. Br Dent J 217, E25 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2014.1121

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2014.1121