Key Points

-

Provides an overview of the clinical indicators of root resorption.

-

Explains the role of modern imaging in classifying resorptive lesions.

-

Discusses the management of resorption considering classification and aetiology.

-

Provides algorithms for practitioners to follow when considering the diagnosis and management of resorption.

Abstract

In this second paper the clinical indicators of root resorption and their diagnosis and management are considered. While the clinical picture can be similar, pathological processes of resorption vary greatly from site to site and this paper proposes appropriate approaches to treatment for teeth that are affected by resorption.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Root resorption has been defined as the loss of dental hard tissue as a result of osteoclastic cell action1 and can occur on both external and internal surfaces. The process can be self limiting and is often sub-clinical as seen in the case of surface resorption.2 It can, however, be more progressive and potentially destructive.2 The resorptive process has been classified as being internal or external to the tooth with a number of sub-classifications.3 Internal resorption is inflammatory in nature but the resorptive process may have a replacement component with tissue of mixed origin being deposited within the canal.4 This tissue can be calcific.4 External root resorption can be classified as being surface, inflammatory, cervical or replacement resorption.2 Although the clinical picture may be similar and any difference appears only to be related to the site of resorption, the pathological processes are somewhat different and thus demand different treatment protocols. Accurate and early diagnosis of resorption is critical for successful treatment. This paper considers diagnosis and proposes appropriate approaches to treatment for teeth that are affected by resorption.

Diagnosis

History

Diagnosis should be based upon a sound clinical history. Teeth affected by resorption lesions are often asymptomatic and may present as an incidental finding upon radiographic examination so it is essential that the clinician should pay particular attention to aspects of the history that may play a role in the development of resorption.

These factors include:

-

History of crown preparation6

-

History of pulpotomy6

-

Use of intra-pulpal chemicals such as internal bleaching products9,10,11

-

History of surgical procedures in proximity to the affected roots

-

In more extensive resorptive conditions involving multiple teeth it may be of interest to discuss if the patient has any contacts with cats (see below).16

For a more extensive review of possible aetiological factors that may be elicited from the history the reader should refer to the first of these papers.17

Clinical examination

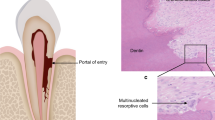

Full extra and intra oral clinical examinations should be performed before more specific investigations of the relevant teeth are carried out. The colour of the tooth should be noted with specific reference to precise site of any discolouration (Fig. 1). In the cervical portion of the teeth pinkish colouration is indicative of resorption. The presence of all restorations should be recorded and note made of primary disease, leaking margins and recurrent caries. The use of percussion is of relevance in resorption cases and thus should be noted and compared to adjacent teeth: a metallic sound may suggest a diagnosis of ankylosis. An increase in mobility may indicate attachment loss or pathological fracture due to extensive external resorption. This should be compared by recording the mobility of the adjacent teeth. A complete loss of physiological mobility may also indicate an ankylosed tooth. After a basic periodontal examination has been recorded, note should be made of any pocketing in relation to the teeth under investigation. Subgingival cavities may be noted on pocket charting. These should be probed and the nature of the cavities described.

Radiographic examination

If resorption is suspected one or more periapical radiographs should be taken. Panorals do not provide sufficient detail for the diagnosis of smaller lesions.18 Parallax radiographs should be considered as this technique will yield further information about the site and type of lesion. Using the 'same lingual, opposite buccal rule' (SLOB) the shift of an external lesion can be detected. Internal lesions, however, should remain in a similar position relative to the root canal (Figs 2a-c).19

Following parallax radiography the lesion shifts in the opposite direction as the film indicating the lesion is buccally situated and thus external. Note also the walls of the canal clearly visible throughout the lesion. The poor prognosis is confirmed when CBCT was used to quantify the extent of the lesion

The limitations of routine dental radiography are widely known.20,21,22 Superimposition of anatomical features, inadvertent distortion when film holders are used and the two-dimensional nature of the image may result in a less than ideal image. Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that radiographs may not be sufficiently sensitive to enable diagnosis of external resorptive lesions.18 The size of the lesion, its location, local anatomy and bone density have all been demonstrated to influence the detection of lesions.23,24,25 Small resorptive cavities and those present on buccal and lingual surfaces are more likely to remain undiagnosed.23,25,26 Significant differences in inter and intra-rater detection of resorption have been demonstrated.27,28 Thus clinicians should be aware of these limitations, examine radiographs under appropriate conditions and refer for an opinion for further imaging if in doubt.

Cone beam computed tomography (CBCT)

A number of case reports have demonstrated that CBCT can enhance the diagnosis of resorptive lesions.29,30,31 These have been further supported by clinical studies though most are in vitro.32,33,34 The one in vivo study had a small sample size.22 The use of CBCT enables the precise determination of site, type and extent of the lesion. There has been an increase in the number of publications related to the use of CBCT for diagnosis of both internal and external lesions although many are case reports.30,35,36,37 Most clinical studies are related to artificially generated root lesions.34,38,39 Nonetheless the indications are that CBCT is of value in the diagnosis, and ultimately the management of resorption (Figs 3a-c and 4a-c).22 As exposure to ionizing radiation must be kept to a minimum, referral for CBCT should only be made if it will be of significant assistance in diagnosis or management. Figure 5 presents a simple algorithm that may be used to help classify lesions radiographically and indicates when CBCT may be of value.

For further information upon the use of CBCT in dentistry readers are directed towards the European guidelines on dental CBCT at http://ec.europa.eu/energy/nuclear/radiation_protection/doc/publication/172.pdf. This comprehensive report reviews the current evidence pertaining to the use of CBCT in dental and maxillofacial imaging and provides evidence-based guidelines for clinicians using or seeking to use CBCT as a diagnostic and treatment planning aid.

At this point the clinician may have come to a reasonably accurate diagnosis, although not necessarily the extent of the lesion or the possible management options. In order that resorption can be accurately diagnosed and classified careful examination and use of any appropriate special tests are essential. Each type of lesion bears certain characteristics and it is only following accurate diagnosis that the correct form of treatment can be instigated.

In the following section different forms of resorption are considered.

External surface resorption

Surface resorption is usually sub-clinical. Radiographically it may be seen as cavitation in the cementum and dentine, or an alteration of the root contour.40 There is no corresponding inflammatory response in the periodontal ligament and there is no destruction of adjacent alveolar bone.41 This type of resorption is self limiting and, if diagnosed, no further treatment is necessary.40

External inflammatory resorption

External root resorption is often sub-clinical unless there is an acute inflammatory process and the tooth becomes tender to pressure or there is an associated swelling or the reduced support leads to mobility. The resorptive lesion is often an incidental radiographic finding. Presentation will vary depending upon whether the process is infective or sterile.

Sterile inflammatory resorption

Associated with pressure including orthodontics, impacted teeth etc (Figs 6a and b), radiographic evidence of causative pathology such as ectopic tooth/ bony pathology and radiographic shortening and blunting of the root apices related to the upper anterior teeth.42 The extent of the shortening is variable but the apices are classically rounded. These teeth usually give a positive response to vitality testing. If there is a history of trauma, the extent of the resorption may be more extensive and there may be a loss of vitality. If there is a superimposed infective process the resorption may be far more aggressive with more extensive and irregular root destruction.

Infective inflammatory resorption

Associated with trauma and/or pulpal necrosis (Figs 7a, b and 8). The canal can often be visualised radiographically.19 When the process is related to an endodontic stimulus alone the resorptive area is associated primarily with the apex or a lateral canal or both.

Associated with radiographic irregular concavity/concavities: bowl shaped resorption of the root and a corresponding radiolucency in the bone.43 May appear moth-eaten.

In the mildest form there may simply be a local loss of architecture but in severe forms there can be extensive loss of hard tissue.

In avulsion injuries the site may be potentially anywhere at which the periodontal ligament and the cementum have been damaged due to the trauma or via adverse environmental conditions such as dehydration if inappropriately stored.

These teeth will give a negative response to vitality testing.6

External cervical resorption

Resorptive lesions on the external cervical aspect of the tooth are often symptomless though there may be a sensation of mild discomfort or irritation from the surrounding gingival tissues.44 Initially there would not be pulpal involvement45 but if the lesion is significantly advanced there may be pulpitic symptoms as a communication with the pulp may ensue.4 Thus pulpitic symptoms may arise and these may precede those of periapical disease. Clinically, it may be that cervical resorption is only detected when the lesion is in close proximity to the crown (Figs 9a-d).

Other signs of external cervical resorption:

-

The cervical enamel and root surface may appear to be pink due to vascular granulation tissue within the resorptive cavity.1

-

Probing may elicit profuse bleeding46

-

The edges of the cavity may be palpated as being sharp and thinned

-

Probing of the cavity reveals a hard, rough surface and distinguishes resorption from caries47

-

A purulent exudate indicates a superimposed infective process

-

Unless the lesion is very extensive, the tooth will be positive to vitality testing as the pulp will not be involved

-

Mobility of the coronal portion may be indicative of a pathological fracture.

Diagnosis can be problematic if the cavity cannot be visualised and assessed easily intra-orally. In such cases, external cervical resorption is notoriously difficult to distinguish from internal resorptive lesions.44,48 Both may present with a 'pink spot' though the origin and histopathology of these varies. Differentiation between the two is largely based upon radiographic examination using the parallax technique. Radiographically features may include:

-

Asymmetric irregular radiolucency in the cervical region of the root

-

Possible corresponding loss of alveolar bone49

-

Interproximal lesions may be diagnosed more readily and thus earlier but care should be taken to differentiate these from cervical burnout on radiographs

-

The periphery of the lesion may be irregular and appear to be superimposed upon the outline of the pulp cavity50

-

In more advanced cases the lesion may be multilocular and mottled if these is fibro-osseous tissue in the cavity50

-

The root canal may reveal a loss of radiographic continuity in advanced disease.

Conventional radiography does not allow for three dimensional imaging and assessment of ECR lesions.31 As such CBCT is a valuable diagnostic aid and offers the potential for accurate assessment of the extent of the lesion and aids treatment planning.21,30,31

Heithersay subdivided cervical resorptive lesions into four categories (Fig. 10):51

-

Class 1 lesions just penetrate the root dentine of the cervical area

-

Class 2 lesions are deeper and in closer proximity to the pulp but remain within coronal dentine (Figs 11a and b)

Figure 10 Heithersay's classification of cervical resorption51

-

Class 3 lesions are more extensive and involve the coronal third of the root. (Figs 12a and b)

-

Class 4 lesions extend into the coronal half of the root dentine and may completely envelop the pulp: there is a possibility of pulpal involvement (Fig. 13).

If three or more teeth show signs of resorption and there is no clear cause factor a diagnosis of multiple idiopathic resorption should be considered. (Figs 14a and b)

In the panoral radiograph of 2008 the retained roots of the lower central incisors are evident and there is a large resorptive cavity in the lower left lateral incisor tooth 32. Within three years a similar lesion presented on the lower right lateral incisor and all the lower incisors suffered pathological fractures. This patient had no relevant dental history thus a diagnosis of multiple idiopathic resorption was made

External replacement resorption

There are often no symptoms associated with external replacement resorption (ERR)52 but there may be clinical signs when 10-20% of the root is affected.53 There are three significant clinical manifestations of ERR:

-

A change in percussive sound; the tooth will have a high pitched or metallic sound to percussion.53,54 Simple percussion with the handle of a dental mirror has been demonstrated as a reliable method of diagnosing ERR55

-

A lack of mobility.53,54 Classically this can be assessed with manual palpation of the tooth in a labio-lingual direction and use of the Miller index.56 Electronic gauges such as Periotest may be used but the results must be interpreted with caution57 and a diagnosis made only after corroboration with other signs and symptoms55

-

The tooth may be infra-occlusion.53,58 This will be more severe if the ERR began before the age of 10 years, less severe in the 12-16 year age range and may be minimal if it occurs after pubertal growth and in adulthood.59

In the early stages of ERR there may be minimal or no evidence on radiographs.56 With conventional two dimensional radiography if the ERR is occurring on the labial or lingual surfaces it will not be readily visible.60,61 In more advanced lesions there is complete or partial loss of the lamina dura and, depending upon the extent of the process, the root dentine will appear either irregular or completely 'moth-eaten' as bone progressively replaces dentine. There is an absence of radiolucency (Fig. 15)43

Internal inflammatory resorption

The tooth may have a history of trauma, vital pulp therapy or crown preparation.6

Internal resorption may present as the original characteristic 'pink spot' or Mummery tooth.62 The clastic activity within the pulp space thins the dentine to the point at which the granulation tissue63 of the resorptive cavity lies beneath the enamel, thus the crown of the tooth may have a pinkish hue (Fig. 16).

The tooth is often partially vital and there may be the symptoms of pulpitis63 though vitality testing may be inconclusive. If there is complete necrosis of the pulp the patient may develop signs and symptoms indicative of periapical periodontitis: tenderness to percussion, sinus tract development and/or acute swelling.

Radiographically there will be an oval shaped lacunae within the canal, often spreading symmetrically or eccentrically (Figs 17 and 18).49 If the lesion is not in the most apical portion of the root, it will merge with the normal canal anatomy apical to the resorptive region.48

The margins are sharp, smooth and clearly defined and the canal will not appear present in the area of the lesion.19 As described above, paralleling technique is essential when taking radiographs.

Internal replacement resorption

Internal replacement resorption results in:

-

An asymmetric and irregular enlargement of the pulp canal with distortion of the canal anatomy40,64

-

The canal/pulp may appear to be obliterated or replaced with a mixed radio-opaque area with loss of the root canal walls63

-

This may also appear as a pinkish area in the crown of the tooth

-

Vitality testing may yield a positive response unless there is crown or root perforation.65

Replacement resorption may be very difficult to distinguish from ECR.63 Referral for CBCT may be appropriate if there is doubt.30,66

Management

The fundamental principle related to management of any resorptive lesion is to halt the activity of the osteoclastic cell. This may be by: removing the source of stimulation, reducing osteoclastic activity, stimulating repair or by a combination of methods. In cases of resorption due to pressure it may be possible to remove the stimulus; for example extraction of the impacted canine or to halt active orthodontic treatment. In cases in which the stimulus is necrotic pulpal tissue and bacteria, root canal treatment is key to success. In cases in which the stimulus is damage to the periodontal ligament, cementum or predentine, direct management may be more difficult and treatment should be directed to influencing the osteoclastic cell behaviour.

The decision as to whether or not to treat may be difficult to make. Key considerations will be related to the degree of resorption, the activity of the lesion and the aetiology. Mild resorption related to orthodontic tooth movement for example will not require intervention other than reduction or cessation of forces yet internal resorption of any kind most certainly will. If resorption due to an expanding lesion of unknown aetiology within the cortical bone is evident, immediate referral to the local maxillofacial department is essential. Likewise if the aetiology or extent of a resorptive process cannot be defined, referral to a specialist centre is advisable. Once a diagnosis has been made a management plan can be devised. Heithersay divided the management options for resorptive root lesions into four categories:51

-

Conditions that will respond to conservative endodontic treatment

-

Conditions that will require surgical endodontics

-

Conditions that will require combined therapy, for example, endodontics, orthodontics, periodontics and prosthodontics

-

Conditions that will not respond to or do not require any treatment.67

Treatment should be initiated only if it will improve the prognosis of the tooth. All treatment should be performed under optimal conditions including a good light source and magnification.

External inflammatory resorption: prevention

Maintenance of vitality

Prevention of external root resorption is essential. Patients at risk of dental trauma should be provided with custom made gum shields to be worn when the risk is present.68 Those patients with a Class II Division 1 incisor relationship should be advised about the benefits of orthodontic treatment.69,70 Those at risk of trauma and those who work with people at risk of trauma should be instructed in the judicious management of traumatised teeth and the optimum handling of avulsed teeth. Ideally, avulsed teeth should be immediately gently manipulated back into place.71 If replantation is not possible the tooth should be stored in a suitable medium. Sterile saline is an excellent medium but may not be readily available. Milk is often at hand, but if not, simply placing a tooth under the tongue may be adequate to reduce the drying time of the periodontal ligament and provide optimum conditions for cell survival.71 The period of time the tooth is extra-oral is critical: if the extra-oral period exceeds 90 minutes, healing is significantly lowered.43

The patient should visit the dentist immediately and the tooth/teeth splinted with a functional splint for up to two weeks (Figs 19a and b).71 If there is damage to the alveolar bone the tooth may not be easily repositioned as the socket may be damaged also. Patients presenting with trauma or history of trauma to the dentition should be kept under regular clinical and radiographic review. Prescription of antibiotics is wise, especially if there has been suspected contamination of the wound or tooth at injury. Tetracycline has been recommended as the antibiotic of choice as it has substantial anti-bacterial as well as anti-resorptive properties.72 In addition to antibiotics, steroids have been demonstrated to have anti-resorptive properties. The routine use of Ledermix paste in the root canal has been advocated as this material contains both tetracycline and corticosteroids.73 The use of Emdogain has also been advocated for improving both periodontal cell survival after avulsion and periodontal ligament repair.74

Closed apex or open apex?

Revascularisation and maintenance of vitality is possible in teeth with incomplete apex formation if the tooth is replanted within 60 minutes of avulsion.75,76 If the apex is radiographically less than 1.1 mm in diameter this indicates incomplete formation.76 Prevention of bacterial contamination is paramount in the drive for successful replantation therefore emersion in doxycycline has been shown to improve success.77 Nonetheless approximately only 50% of such teeth may maintain vitality.6 If the apex is closed, patients should be advised about the merits of elective endodontics, which should ideally be performed in seven to ten days.78 As the tooth is theoretically vital at replantation single visit root canal treatment may be performed if begun within seven to ten days. It may, however, be prudent to dress the tooth with calcium hydroxide and definitively obturate when healing is more advanced and the splint removed. This should be completed within one month (Figs 20a and b).6 For further information about the management of avulsed teeth the reader should refer to the International Association of Dental Traumatology guidelines published in Dental Traumatology in 2007.71

External inflammatory resorption: damage limitation

If resorption is diagnosed treatment must be considered: resorption may be rapid, resulting in tooth loss in as little as two months.43 Management is largely based upon the aetiology: whether the process is sterile or infective. If the stimulus is sterile due to orthodontic tooth movement treatment should not necessarily be discontinued but the forces should be reduced. If resorption is due to stimulation from an infective process the stimulus should be halted and orthograde endodontics is the treatment of choice. Endodontic therapy undertaken to a high standard results in favourable outcomes in cases of resorption.79 This can be complicated by the loss of apical constrictions if the resorptive cavity surrounds the terminus of the root (Figs 21 and 22). It is wise to favour a multiple visit approach as it is know that chemo-mechanical disinfection may not eradicate all pathogens. Corticosteroid/antibiotic pastes have been recommended as their placement has been seen to be associated with reduction of resorptive cells.80 However, calcium hydroxide remains the gold standard81 as it eradicates bacteria, may necrotise cells in the resorptive lacunae, neutralise the acidic environment of the lacunae and also stimulate repair.49,82,83 Long term placement of calcium hydroxide has a significant negative effect upon fracture resistance of dentine.84 As such dressings should not be left in situ for over 30 days.84 Regular reviews are essential. Following this routine orthograde obturation should be performed. Surgical endodontics may be required when an orthograde approach is not possible. This would classically occur when there is impediment to the canals such as the presence of a post retained crown. An apparent lack of patency may also indicate a surgical approach (Figs 23a-d).

EIR associated with impacted teeth and/or expanding infra-bony lesions

Where impacted teeth are involved in a resorptive lesion several factors must be considered:

-

Is the impacted tooth valuable for dental aesthetics and function?

-

If so, can the impacted tooth be exposed and aligned?

-

Is the resorption so extensive that extraction of the affected tooth must be considered?

-

Will removal of the impacted tooth have other associated morbidity?

Thus although removal of the associated stimulus (the impacted tooth) will halt the resorptive process,6 extra consideration must be given to further consequences of this, anticipating the importance of attempting to keep the impacted tooth and the long-term prognosis of the affected tooth (Fig. 24).

The management of resorption associated with expanding lesions is difficult and guided largely by the type of pathology involved. It is not within the remit of this article to discuss management of the non-infective infra bony pathologies themselves but the options invariably are related to excision of the lesion or local management. If a bony lesion is deemed so threatening that recurrence or significant expansion is likely, excision may be the only option. In this case the teeth will often be extracted as part of the excision. If non-excisional management is planned the lesion may be accessed, enucleated and/or curettage performed. As with the above example, some lesions may simply be drained. In these instances teeth may be left in situ. Orthograde root canal treatment will often be necessary as loss of vitality is common (Figs 25a and b).

The 21, 22 and 23 have all been rendered non-vital and resorptive activity initiated on the root surfaces. Extraction was contra-indicated as the risk of osteoradionecrosis was high and the patient had an additional risk of bisphosphonate induced osteonecrosis. The teeth were dressed with calcium hydroxide/iodoform (TG PEX -Technical & General Ltd)

External cervical resorption

Several factors have been associated with the stimulation of cervical resorption.51 Prevention is therefore important and this is especially apparent when internal bleaching is concerned.9,10 If there is a cervical defect that may expose external root surface to internally placed bleaching products these should be managed before treatment.85 Once the access cavity has been prepared, the gutta percha and floor of cavity should be sealed to prevent passage of the bleaching agent through the dentine. It is recommended this is at least 2 mm thick. This can be done with glass ionomer, composites or materials such as Cavit or IRM.86 The restorative material should be placed at the level of the cemento-enamel junction. This can be ascertained by using a BPE or William's probe to measure the distance from incisal edge to CEJ externally and ensuring that this length is not exceeded internally.87 Carbamide peroxide 35% and sodium perborate with water have both been proposed as being suitable alternatives to hydrogen peroxide.88 Other factors associated with cervical resorption include surgery/surgical trauma and periodontal therapy. In both these instances clinicians should strive to avoid damage to the root cementum and periodontal ligament where possible.89 As with apical resorption associated with orthodontics, a correlation with orthodontics and cervical resorption has been suggested.51 Thus excessive tipping force pressure should be minimised.

The focus of treatment is to access the resorptive lesion, remove resorptive tissue and restore the cavity.50 The site, extent and pulpal involvement of the cervical resorptive lesion will dictate the treatment protocol. Heithersay suggests that Class 1-3 lesions are restorable but Class 4 lesions rarely so.89 In addition, Class 3 and 4 lesions may present additional challenges: the presence of 'ectopic, bone-like' deposits within the cavity and multiple connections with the periodontal ligament that may impede complete curettage.40 If the lesion is readily accessible and appears radiographically less advanced, direct non-surgical access may be possible.40 If available CBCT will help establish the restorability without exploratory intervention31 but in many instances surgical exposure of the lesion is the only way of truly assessing the site and planning treatment. Alternative methods of treatment have been proposed. These include:

-

Orthodontic extrusion, treatment of the lesion and orthodontic re-intrusion40

-

Access and management of the lesion from an internal approach alone90

-

Extraction, management of the lesion and replantation90

-

Do nothing.40

Ultimately, none of these alternative treatment methods are without limitation or risk of failure. As such, simple, direct surgical approach remains the mainstay of sensible treatment planning for lesions that cannot be accessed non-surgically.91

If there is pulpal involvement or suspected near pulpal involvement root canal treatment should be performed. Heithersay recommends that root canal treatment should be instituted then the canal protected with a spreader before performing the surgical repair and finally completing the obturation.40 It may, however, be more prudent to perform endodontic treatment electively beforehand. A full thickness flap should be raised to allow maximum visualisation and access to the site. Whether a surgical or non-surgical approach has been undertaken once the lesion has been accessed management is largely the same: the site should be ideally isolated with rubber dam and sealant paste. The area should be thoroughly curetted until no bleeding is present and the cavity walls are sound. This will ensure that the vascular supply is not maintained and remaining resorptive cell front is removed and there is less likelihood of recurrence.40 The cavity may be conditioned with 90% trichloroacetic acid. It is thought this process may improve the removal of resorptive cells to an extent not possible with mechanical debridement alone (and simultaneous removal of this tissue will minimise bleeding).51,92 Lavage with sodium hypochlorite and scrubbing with EDTA has also been advocated.93 In Class 3/4 lesions, Heithersay92 recommends placing an intra-canal medicament, Ledermix paste (Blackwell), in the first visit (if RCT has not already been performed) and temporary dressing of Cavit (3M ESPE) in the resorptive cavity. Ten to 14 days later the site is reopened, if necessary further curettage performed, endodontic treatment completed and a permanent restoration placed in the resorptive cavity.

A range of materials may be used for restoration of the prepared cavity. Heithersay suggests the use of a glass ionomer.89 The cavity can also be restored with composite (Figs 26a-f).6 The clinician should be guided by the conditions; composite will not be an option if isolation cannot be guaranteed. Mineral trioxide aggregate is an appropriate restorative material. It is biocompatible and has excellent sealing abilities plus the setting process requires moisture, which is ideal for such lesions.94,95 Indeed it is possible there could be regeneration of the periodontium as this has been shown to occur when the material is used as a retrograde obtundant in endodontics.96 It is, however, difficult to handle and may 'wash out' in larger cavities. Although there is a paucity of data to support their use, newer materials such as Biodentine (Septodont) may prove to be the material of choice. Like MTA it consists of tricalcium silicate as well as calcium carbonate and zirconium oxide. As is the case for MTA, there is an uptake of silicone and calcium into adjacent dentine. The former is thought to have a bioactive role, inducing local remineralisation. The latter forms calcium phosphate precipitates: apatite crystal formations at the boundary of material and dentine. These may result in improved physical strength and acid resistance.97

A full thickness muco-periosteal flap was raised to access the resorptive lesion, the area was curetted and the margins prepared. (a) Composite resin was placed (b) and the restoration re-contoured. The flap was replaced and sutured (c) with 5-0 Prolene (Ethicon, Inc, Johnson & Johnson). (d) shows the site at three month review. (e) and (f) show the radiographic appearance before and after restoration

In teeth exhibit external cervical resorption aesthetic considerations are paramount. Periodontal reattachment may not occur if the tooth has been restored with traditional restorative materials, so a periodontal defect may remain or the tissues may migrate apically resulting in compromised aesthetics.40 Mineral trioxide aggregate may discolour and therefore may be contraindicated for restoration of anterior lesions. Clinicians may also consider the use of guided tissue regeneration after definitive repair to promote a differential tissue response and potentially heal regeneration of periodontal ligament (PDL).98,99 This may only be appropriate when the muco-periosteal flap can be placed at least 2 mm coronal to the defect margins.99 The use of root surface conditioning agents and enamel matrix proteins to promote regeneration has been shown to be effective for certain periodontal defects.100,101,102 This technique is simpler than GTR as no membrane is required.9 Although of theoretical interest, there is a paucity of data to demonstrate the benefit of Emdogain after repair of resorptive lesions.

Management of multiple idiopathic cervical resorption lesions is challenging due to the progressive nature of the condition. The only definitive solution is extraction.103 Surgical exposure, lesion curettage and restoration with various materials have been described.104,105 CBCT is useful in diagnosis. The site predisposes to attachment loss and periodontal disease therefore long-term supportive periodontal therapy is essential.104 Finally, lesions tend to recur. Neely and Gordon106 reported the follow-up of two patients, a father and son, over 22 years and despite eight procedures five extractions were required in the father. The son exhibited evidence of resorption in both maxillary first molars. Despite intervention the upper left first molar was extracted.106 In these patients tooth loss is inevitable thus both patients and clinicians should accept any restorative intervention cannot prevent disease progression but may improve aesthetics and control pulpitic symptoms. All patients should be subject to regular clinical and radiographic reviews. Currently there are no guidelines about the frequency of reviews for two or three dimensional imaging so sensible patient focused decisions should be made.

External replacement resorption

Once ERR is established there is no effective treatment. Progression will result in complete resorption of the root and eventual crown fracture. In older patients the progression is slow and may not require immediate treatment, indeed the tooth may last for years as a functional and aesthetic unit.107 In younger patients, before or during the pubertal growth phase, the progression of ERR is more rapid and the need for further treatment must be anticipated.107 The patient should be informed of this and routine monitoring should be instigated to allow more accurate prediction of when elective intervention may be necessary. Furthermore in the younger patient ankylosis may interfere with vertical development of the alveolar process.52 This may lead to improper function and compromised aesthetics. Thus, early intervention is essential. For management of ERR the following options maybe considered:

1. Accept position, restore the incisal level with composite and monitor

It is possible in the short to medium term to simply build an infra-occluded tooth up in composite to improve the aesthetics. This may be of further use in bone preservation before implant placement. In younger patients before or during the pubertal growth phase this option may not be suitable as the normal development of the alveolar process can arrest if the tooth is left in situ. In addition the tooth may be unacceptably long if restored and thus the aesthetics may remain significantly compromised.52

2. Autotransplantation

Autotransplanation with a premolar has been proposed as a management technique.108,109 Apical development of the donor tooth must be considered and elective endodontic therapy of the tooth performed if the apex is fully developed as these teeth carry a higher risk of pulpal necrosis.109 Careful preoperative planning and atraumatic surgical technique are essential.110 Once transplanted the donor tooth can be disguised to give the appearance of the lost tooth. Contraindications to such an approach include: gross discrepancies in donor tooth and recipient site size or proposed tooth shape, the possible need for future orthodontics, systemic health problems, patients older that 12-14 years and excessive damage to the alveolus of the recipient site.111,112

3. Surgical repositioning

Extraction and replantation of the tooth has been advocated, theoretically breaking bony contact with the root and promoting healing.113 The tooth is extracted and replaced correcting vertical and/or horizontal discrepancies and functionally splinted or orthodontically anchored.114,115 A technique involving extraction of the tooth, reinforcement and augmentation with a titanium post and replantation met with limited success.116 There is a paucity of evidence to support such treatment plans.52

4. Extraction

In adults a tooth with ERR may survive up to 20 years as the disease process is slow.107 As such extraction would only be indicated if pathological fracture occurred or deemed likely or aesthetics were severely compromised. In children this should not be performed immediately after diagnosis but timed in conjunction growth phases.117 It has been suggested that extractions of teeth with ERR in children should be timed with the start of the adolescent growth spurt:118 10.5-13 years old for girls and 12.5-15 years old for boys.119 Thus maintaining space and aesthetics up to the time of extraction while allowing vertical alveolar growth during puberty. Extraction of teeth with ERR is notoriously difficult, necessitating a surgical approach. As such there can be considerable bone loss and the defect may be worse.120,121 This may complicate both implant-based and convention restorative planning.122,123 If extraction is planned, socket/ridge preservation may be considered to minimise alveolar resorption.124

After extraction the patient may have the space filled with a conventional fixed or removable prosthesis, an implant and prosthesis or have orthodontic space closure, expansion or maintenance in preparation for a restorative solution. Orthodontic space closure may not always be viable and the aesthetic outcome may be compromised with discrepancies in tooth size and symmetry. Furthermore, existing malocclusions, compromised dental health, cost of treatment and compliance problems may complicate or contra-indicate orthodontics.117

5. Decoronation

This may be regarded as a suitable alternative to extraction. It is indicated when the root is not expected to resorb within a year and/or the site is planned for routine restorative or implant retained prosthesis.117 It should not be considered if orthodontic space closure is planned. In the adult patient this may be considered two years before implant placement.117 In the growing child it may be indicated when the infraposition of the tooth advances to or beyond a quarter of the position is should be in.59,121 Decoronation prevents extensive bone loss associated with extraction and preserves alveolar ridge height and width.121 Furthermore, it can be viewed as elective management when pathological fracture is likely or aesthetics are severely compromised.117 The suggested technique for decoronation is:

-

Raise a full thickness mucoperiosteal flap

-

Remove the crown using rotary instrument and smooth the root face to be flush with or just below the alveolar crest

-

Removal of any root filling/medicament that may induce inflammation or prevent bony growth

-

Covering the root surface with a full thickness mucoperiosteal flap121,125

Many of these techniques require specialist care. A recent Cochrane review indicates that there is very little evidence as to the optimal treatment option when management of the ankylosed tooth is concerned.126 Extraction of these teeth is not without risk and the surgical deficit may be significant, potentially complicating future implant placement. Patients must consent to such associated morbidity. If pathological fracture is predicted, elective decoronation and provision of an overdenture or fixed prosthesis may be the optimum solution. Timing of intervention can be critical to minimise morbidity and optimise outcomes.

A recent proposal has been the management of terminal replacement resorption with the use of calcitonin. The rationale derives from the management of patients with osteoporosis. As the process of boney resorption is essentially similar to dental hard tissue resorption it is logical to assume that treatment rationales for catabolic bone disorders may also be advantageous for dental resorptive disorders. Drugs used include calcitonin, prostaglandin E2 and more notably for the dental profession, bisphosphonates. One study has demonstrated that bisphosphonates have no influence upon resorptive activity when used as an intra-canal medicament in replanted teeth.127 Others have indicated a more positive outcome for modification of osteoclastic behaviour when lesions are treated with bisphosphonates.128,129 Limited conclusions can be extrapolated to the human model as these are in vitro or on animal models. The side effects of bisphosphonate therapy would likely render this treatment regimen unjustifiable to the majority of patients with resorptive lesions. A reasonable argument could perhaps be constructed for bisphosphonate therapy in patients with multiple-idiopathic resorptive lesions.

An algorithm for the management of external type resorptive lesions can be found in Figure 27.

Internal inflammatory resorption

The aim of treatment in internal resorption cases is to remove any stimulus and vital tissue that may be allowing the resorptive process to perpetuate. If the tooth is restorable, root canal treatment is usually the treatment modality of choice.130 Endodontic therapy associated with internal resorption should be considered in two phases: chemomechanical debridement and obturation.

Chemomechanical preparation

Access should be minimal to preserve maximum tooth structure. In inflammatory resorptive cases the process can be complicated by excessive haemorrhage from the canal. If bleeding cannot be controlled, a perforation or a misdiagnosis and external cervical resorption may be considered.6 Furthermore if there is a replacement resorption the canal may be partially or completely obstructed. The former can be managed by mechanical extirpation of the pulp tissue with copious lavage. If there are anatomical discrepancies or blockages, the canal form is often impossible to clean mechanically although long shank burs and diamond tipped endosonics may help. Chemical disinfection of the canal system therefore must be considered essential, hypochlorite being the irrigant of choice.131 Passive ultrasonic irrigation may be used as an adjunct.132 The combination of cavitation and acoustic streaming produced by the use of ultrasonics can further aid both chemical and mechanical cleansing.133

Even with this combination it may be impossible to totally eliminate bacteria from the irregular crypts of the resorptive area.134,135 Intra canal medicaments must be used to further decontaminate the intricacies of the canal system thus single stage root canal treatment is not advocated. The current modus operandi is for the placement of an inter appointment calcium hydroxide paste.136 The combination of sodium hypochlorite and calcium hydroxide has been shown to significantly reduce the number of bacteria (Fig. 28).137

Obturation

Consideration must be given to obturation of both the canal apical to the resorptive cavity and the resorptive cavity and coronal canal. The apical portion may be obturated with cold lateral condensation, warm vertical compaction or continuous wave compaction. Flowable gutta percha and vertical condensation is then necessary for optimum three-dimensional obturation of the resorptive cavity (Figs 29a-b and 30).133,138,139 Carrier-based systems may not obturate the resorptive cavity. If the lesion has perforated the canal wall it has been shown that mineral trioxide aggregate (MTA) is the material of choice for repair.140 Case reports suggest the canal should be obturated with gutta-percha to the level of the lesion and an MTA dressing placed to fill the cavity.141,142 A muco-periosteal flap may have to be raised to ensure isolation and complete obturation of the perforation. Where there is no perforation and the remaining tooth is not significantly undermined the prognosis is good for treatment of internal resorption.143 See Figure 31 for an algorithm to aid in the management of internal resorption.

Internal replacement resorption

Management protocols should follow that for internal inflammatory resorption but the clinician must be aware of an additional level of complexity owing to calcific tissue within the canal. The lesion should be throughly curetted. The application of 90% trichloracetic acid may help inactivate the lesion.40,92 The use of endosonics may aid removal of mixed calcific tissue obstructing access. Orthograde root canal treatment may not be possible and surgical endodontics may be considered to be the only option.

An algorithm for the management of internal type resorptive lesions can be found in Figure 31.

Conclusions

Resorption presents with a range of aetiologies and prognoses. A thorough understanding of the pathology is essential to allow appropriate treatment planning. Management can be challenging. Timely intervention is essential for optimum management. Practitioners must be aware of when to intervene and have the confidence to do so. Delays in treatment via late diagnoses and referral waiting times may be catastrophic. The outcome for treatment may be uncertain and patients should always be well informed of this. This review presents algorithms for treatment planning which should assist management of resorptive lesions in a timely and appropriate fashion thus improving the long term prognosis for teeth presenting with resorptive defects.

References

Patel S, Ford T P . Is the resorption external or internal? Dent Update 2007; 34: 218–220, 222, 224–226, 229.

Andreasen J O . External root resorption: its implication in dental traumatology, paedodontics, periodontics, orthodontics and endodontics. Int Endod J 1985; 18: 109–118.

Andreasen J O . Luxation of permanent teeth due to trauma. A clinical and radiographic follow-up study of 189 injured teeth. Scand J Dent Res 1970; 78: 273–286.

Wedenberg C, Zetterqvist L . Internal resorption in human teeth - a histological, scanning electron microscopic, and enzyme histochemical study. J Endod 1987; 13: 255–259.

Andreasen J O, Andreasen F . Root resorption following traumatic dental injuries. Proc Finn Dent Soc 1992; 88(Suppl 1): 95–114.

Trope M . Root resorption due to dental trauma. Endodontic Topics 2002; 1: 79–100.

Mattison G D, Delivanis H P, Delivanis P D, Johns P I . Orthodontic root resorption of vital and endodontically treated teeth. J Endod 1984; 10: 354–358.

Cwyk F, Saint-Pierre F, Tronstad L . Endodontic implications of orthodontic movement. J Dent Res 1984; 63: 286.

Heithersay G S . Invasive cervical resorption. Endodontic Topics 2004; 7: 73–92.

Harrington G W, Natkin E . External resorption associated with bleaching of pulpless teeth. J Endod 1979; 5: 344–348.

Cvek M, Lindvall A . External root resorption following bleaching of pulpless teeth with oxygen peroxide. Endod Dent Traumatol 1985; 1: 56–60.

Nitzan D, Keren T, Marmary Y . Does and impacted tooth cause root resorption of the adjacent one? Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1981; 51: 221–224.

Chu F C, Li T K, Lui V K, Newsome P R, Chow R L, Cheung L K . Prevalence of impacted teeth and associated pathologies — a radiographic study of the Hong Kong Chinese population. Hong Kong Med J 2003; 9: 158–163.

Karring T, Nyman S, Lindhe J, Sirirat M . Potentials for root resorption during periodontal wound healing. J Clin Periodontol 1984; 11: 41–52.

Magnusson I, Claffey N, Bogle G, Garrett S, Egelberg J . Root resorption following periodontai flap procedures in monkeys. J Periodontal Res 1985; 20: 79–85.

von Arx T, Schawalder P, Ackermann M, Bosshardt D D . Human and feline invasive cervical resorptions: the missing link? — Presentation of four cases. J Endod 2009; 35: 904–913.

Darcey J, Qualtrough A . Resoprtion: part 1. Pathology, classification and aetiology. Br Dent J 2013; 214: 439–451.

Laux M, Abbott P V, Pajarola G, Nair P N . Apical inflammatory root resorption: a correlative radiographic and histological assessment. Int Endod J 2000; 33: 483–493.

Gartner A H, Mack T, Somerlott R G, Walsh L C . Differential diagnosis of internal and external root resorption. J Endod 1976; 2: 329–334.

Patel S, Dawood A, Whaites E, Pitt Ford T . New dimensions in endodontic imaging: part 1. Conventional and alternative radiographic systems. I Endod J 2009; 42: 447–462.

Patel S, Dawood A, Ford T P, Whaites E . The potential applications of cone beam computed tomography in the management of endodontic problems. Int Endod J 2007; 40: 818–830.

Patel S, Dawood A, Wilson R, Horner K, Mannocci F . The detection and management of root resorption lesions using intraoral radiography and cone beam computed tomography - an in vivo investigation. Int Endod J 2009; 42: 831–838.

Andreasen F M, Sewerin I, Mandel U, Andreasen J O . Radiographic assessment of simulated root resorption cavities. Endod Dent Traumatol 1987; 3: 21–27.

Bender I B . Factors influencing the radiographic appearance of bony lesions. J Endod 1982; 8: 161–170.

Goldberg F, De Silvio A, Dreyer C . Radiographic assessment of simulated external root resorption cavities in maxillary incisors. Endod Dent Traumatol 1998; 14: 133–136.

Chapnick L . External root resorption: an experimental radiographic evaluation. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1989; 67: 578–582.

Goldman M, Pearson A H, Darzenta N . Endodontic success – who's reading the radiograph? Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1972; 33: 432–437.

Goldman M, Pearson A H, Darzenta N . Reliability of radiographic interpretations. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1974; 38: 287–293.

Patel S, Kanagasingam S, Mannocci F . Cone beam computed tomography (CBCT) in endodontics. Dent Update 2010; 37: 373–379.

Cohenca N, Simon J H, Mathur A, Malfaz J M . Clinical indications for digital imaging in dento-alveolar trauma. Part 2: root resorption. Dent Traumatol 2007; 23: 105–113.

Patel S, Dawood A . The use of cone beam computed tomography in the management of external cervical resorption lesions. Int Endod J 2007; 40: 730–737.

Kamburoğlu K, Kursun S . A comparison of the diagnostic accuracy of CBCT images of different voxel resolutions used to detect simulated small internal resorption cavities. Int Endod J 2010; 43: 798–807.

Liedke G S, da Silveira H E, da Silveira H L, Dutra V, de Figueiredo J A . Influence of voxel size in the diagnostic ability of cone beam tomography to evaluate simulated external root resorption. J Endod 2009; 35: 233–235.

Durack C, Patel S, Davies J, Wilson R, Mannocci F . Diagnostic accuracy of small volume cone beam computed tomography and intraoral periapical radiography for the detection of simulated external inflammatory root resorption. Int Endod J 2011; 44: 136–147.

Bandlish R B, McDonald A V, Setchell D J . Assessment of the amount of remaining coronal dentine in root-treated teeth. J Dent 2006; 34: 699–708.

Walter C, Krastl G, Izquierdo A, Hecker H, Weiger R . Replantation of three avulsed permanent incisors with complicated crown fractures. Int Endod J 2007; 41: 356–364.

Maini A, Durning P, Drage N . Resorption: within or without? The benefit of cone-beam computed tomography when diagnosing a case of an internal/external resorption defect. Br Dent J 2008; 204: 135–137.

Lermen C A, Liedke G S, da Silveira H E, da Silveira H L, Mazzola A A, de Figueiredo J A . Comparison between two tomographic sections in the diagnosis of external root resorption. J App Oral Sci 2010; 18: 303–307.

Kamburoglu K, Kurşun S, Yüksel S, Oztaş B . Observer ability to detect ex vivo simulated internal or external cervical root resorption. J Endod 2011; 37: 168–175.

Heithersay G S . Management of tooth resorption. Aust Dent J 2007; 52(Suppl 1): 105–121.

Andreasen J O, Hjorting-Hansen E. Replantation of teeth. II. Histological study of 22 replanted anterior teeth in humans. Acta Odontol Scan 1966; 24: 287–306.

Baumrind S, Korn E L, Boyd R L . Apical root resorption in orthodontically treated adults. Am J Orthodt Dentofacial Orthop 1996; 110: 311–320.

Andreasen J O, Hjorting-Hansen E. Replantation of teeth. I. Radiographic and clinical study of 110 human teeth replanted after accidental loss. Acta Odontol Scand 1966; 24: 263–286.

Gulabivala K, Searson L J . Clinical diagnosis of internal resorption: an exception to the rule. Int Endod J 1995; 28: 255–260.

Wedenberg C, Lindskog S . Evidence for a resorption inhibitor in dentin. Scand J Dent Res 1987; 95: 205–211.

Trope M, Chivian N . Root resorption. In Pathways of the Pulp. Eds Cohen S and Hargreaves K, Ninth edition, Mosby Elsevier.

Liang H, Burkes E J, Frederiksen N L . Multiple idiopathic cervical root resorption: systematic review and report of four cases. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 2003; 32: 150–155.

Makkes P C, Thoden van Velzen S K . Cervical external root resorption. J Dent 1975; 3: 217–222.

Tronstad L . Root resorption - etiology, terminology and clinical manifestations. Endod Dent Traumatol 1988; 4: 241–252.

Patel S, Kanagasingam S, Pitt Ford T . External cervical resorption: a review. J Endod 2009; 35: 616–625.

Heithersay G S . Invasive cervical resorption: an analysis of predisposing factors. Quintessence Int 1999; 30: 83–95.

Andersson L . The problem of dentoalveolar ankylosis and subsequent replacement resorption in the growing patient. Aust Endod J 1999; 25: 57–61.

Andersson L, Blomlöf L, Lindskog S, Feiglin B, Hammarström L . Tooth ankylosis. Clinical, radiographic and histological assessments. Int J Oral Surg 1984; 13: 423–431.

Andreasen J O . Periodontal healing after replantation of traumatically avulsed human teeth. Assessment by mobility testing and radiography. Acta Odontol Scand 1975; 33: 325–335.

Campbell K, Casas M, Kenny D, Chau T . Diagnosis of ankylosis in permanent incisors by expert ratings, Periotest and digital sound wave analysis. Dent Traumatol 2005; 21: 206–212.

Campbell K, Casas M, Kenny D . Ankylosis of traumatized permanent incisors: pathogenesis and current approaches to diagnosis and management. J Can Dent Assoc 2005; 71: 763–768.

Andreasen M, Mackie I, Worthington H . Does it have the properties necessary for use as a clinical device and can the measurements be interpreted? Dent Traumatol 2003; 19: 214–217.

Andreasen J O, Borum M, Jacobsen H, Andreasen F . Replantation of 400 avulsed permanent inciors. 4. Factors related to periodontal ligament healing. Endod Dent Traumatol 1995; 11: 76–89.

Malmgren B . Decoronation: how, why and when? J Calif Dent Assoc 2000; 28: 846–854.

Andersson L . Dentoalveolar ankylosis and associated root resorption in replanted teeth: experimental and clinical studies in monkeys and man. Swed Dent J Suppl 1988; 56: 1–75.

Stenvik A, Beyer-Olsen E M, Abyholm F, Haanaes H R, Gerner N W . Validity of the radiographic assessment of ankylosis. Evaluation of long-term reactions in 10 monkey incisors. Acta Odontol Scand 1990; 48: 265–269.

Mummery J . The pathology of 'pink spots' on teeth. Br Dent J 1920; 41: 301.

Patel S, Ricucci D, Durak C, Tay F . Internal root resorption: a review. J Endod 2010; 36: 1107–1121.

Oehlers F A . A case of internal resorption following injury. Br Dent J 1951; 90: 13–16.

Ne R F, Witherspoon D E, Gutmann J L . Tooth resorption. Quintessence Int 1999; 30: 9–25.

Bhuva B, Barnes J, Patel S . The use of limited cone beam computed tomography in the diagnosis and management of a case of perforating internal root resorption. Int Endod J 2011; 44: 777–786.

Heithersay G S . Clinical endodontic and surgical management of tooth and associated bone resorption. Int Endod J 1985; 18: 72–92.

Johnson T, Messer L . An in vitro study of the efficacy of mouthguard protection for dentoalveolar injuries in de-ciduous and mixed dentitions. Endod Dent Traumatol 1996; 12: 277–285.

Forsberg C, Tedestam G . Etiological and predisposing factors related to traumatic injuries to permanent teeth. Swed Dent J 1993; 17: 183–190.

Burden D . An investigation of the association between overjet size, lip coverage, and traumatic injury to maxillary incisors. Eur J Orthod 1995; 17: 513–517.

Flores M T, Andersson L, Andreasen J O et al. Guidelines for the management of traumatic dental injuries. II. Avulsion of permanent teeth. Dent Traumatol 2007; 23: 130–136.

Sac-Lim V, Wang C Y, Trope M . The effect of systemic tetracycline on resorption of dried replanted dogs' teeth. Endod Dent Traumatol 1998; 14: 127–132.

Pierce A, Lindskog S . The effect of an antibiotic cortico-steroid combination on inflammatory root resorption. J Endod 1997; 14: 459–464.

Filippi A, Pohl Y, von Arx T . Treatment of replacement resorption with Emdogain – preliminary results after 10 months. Dent Traumatol 2001; 17: 134–138.

Yanpiset K, Trope M . Pulp revascularization of replanted immature dog teeth after different treatment methods. Endod Dent Traumatol 2000; 16: 211–217.

Kling M, Cvek M, Mejare I . Rate and predictability of pulp revascularization in therapeutically reimplanted permanent incisors. Endod Dent Traumatol 1986; 2: 83–89.

Cvek M, Cleaton-Jones P, Austin J, Lownie J, Kling M, Fatti P . Effect of topical application of doxycycline on pulp revascularization and periodontal healing in reimplanted monkey incisors. Endod Dent Traumatol 1990; 6: 170–176.

Trope M, Yesilsoy C, Koren L, Moshonov J, Friedman S . Effect of different endodontic treatment protocols on periodontal repair and root resorption of replanted dog teeth. J Endod 1992; 18: 492–497.

Cvek M . Treatment of non-vital permanent incisors with calcium hydroxide. II. Effect on external root resorption in luxated teeth compared with the effect of root filling with gutta-percha. A follow-up. Odontol Revy 1973; 24: 343–354.

Pierce A, Heithersay G S, Lindskog S . Evidence for direct inhibition of dentinoclasts by a corticosteroid/antibiotic endodontic paste. Endod Dent Traumatol 1987; 4: 44–45.

Mohammadi Z, Dummer M . Properties and applications of calcium hydroxide in endodontics and dental traumatology. Int Endod J 2011; 44: 697–730.

Tronstad L, Andreasen J O, Hasselgren G, Kristerson L, Riis I . pH changes in dental tissues after root canal filling with calcium hydroxide. J Endod 1981; 7: 17–21.

Massarstrom L E. L, Blomlof L B, Feiglin B, Lindskog S F. Effect of calcium hydroxide treatment on periodontal repair and root resorption. Endod Dent Traumatol 1986; 2: 184–189.

Andreasen J O, Farik B, Munksgaard E C . Long-term calcium hydroxide as a root canal dressing may increase risk of root fracture. Dent Traumatol 2002; 18: 134–137.

Walton R, Rotstien I . Bleaching discoloured teeth: internal and external. In Walton R, Torabinejad M (eds) Principles and practice of endodontics. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: W B Saunders, 1996.

Rotstien I, Zyskind D, Lewinstein I, Bamberger N . Effect of different protective base materials on hydrogen peroxide leakage during intracoronal bleaching. J Endod 1992; 26: 716–718.

Lim K C . Considerations in intracoronal bleaching. Aust Dent J 2004; 30: 69–73.

Lee G P, Lee M Y, Lum S O, Poh R S, Lim K C . Extraradicular diffusion of hydrogen peroxide and pH changes associated with intracoronal bleaching of discoloured teeth using different bleaching agents. Int Endod J 2004; 37: 500–506.

Heithersay G S . Invasive cervical resorption following trauma. Aust Dent J 1999; 25: 79–85.

Frank A, Torabinejad M . Diagnosis and treatment of extracanal invasive resorption. J Endod 1998; 7: 500–504.

Frank A L, Bakland L K . Nonendodontic therapy for supraosseous extracanal invasive resorption. J Endod 1987; 13: 348–355.

Heithersay G S . Treatment of invasive cervical resorption: an analysis of results using topical application of trichloroacetic acid, curettage, and restoration. Quintessence Int 1999; 30: 96–110.

Dhingra A, Verma M . CBCT and mineral trioxide aggreage in the management of communicating external invasive multiple resorption: a case report. Endod Pract 2011; 14: 18–24.

Camilleri J, Montesin F, Papaioannou S, McDonald F, Pitt Ford T . Biocompatibility of two commercial forms of mineral trioxide aggregate. Int Endod J 2004; 37: 699–704.

Matt G D, Thorpe J R, Strother J M, McClanahan S B . Comparative study of white and gray mineral trioxide aggregate (MTA) simulating a one-or two-step apical barrier technique. J Endod 2004; 30: 876–879.

Camilleri J, Pitt Ford T . Mineral trioxide aggregate: a review of the constituents and biological properties of the material. Int Endod J 2006; 39: 247–254.

Han L, Okiji T . Uptake of calcium and silicon released from calcium silicate–based endodontic materials into root canal dentine. Int Endod J 2011; 44: 1081–1087.

Melcher A H . On the repair potential of periodontal tissues. J Periodontol 1976; 47: 256–260.

Rankow H, Krasner P . Endodontic applications of guided tissue regeneration in endodontic surgery. J Endod 1996; 22: 34–43.

Hammarström L . Enamel matrix, cementum development and regeneration. J Clin Periodontol 1997; 24: 658–668.

Sculean A, Windisch P, Keglevich T, Chiantella G C, Gera I, Donos N . Clinical and histologic evaluation of human infrabony defects treated with an enamel matrix protein derivative combined with a bovine-derived xenograft. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent 2003; 23: 47–55.

Velasques-Plata D, Scheyer E, Mellonig J . Clinical comparison of an enamel matrix derivative used alone or in combination with a bovine-derived xenograft for the treatment of periodontal osseous defects in humans. J Periodontol 2002; 73: 433–440.

Moody A, Speculand B, Smith A, Basu M . Multiple idiopathic external resorption of teeth. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1990; 19: 200–202.

Yu V, Messer H, Tan K . Multiple idiopathic cervical resorption: case report and discussion of management options. Int Endod J 2011; 44: 77–85.

Iwamatsu-Kobayashi Y, Sato-Kuriwada S, Yamamoto T . A case of multiple idiopathic external root resorption: a 6 year follow-up. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2005; 100: 772–779.

Neely A L, Gordon S C . A familial pattern of multiple idiopathic cervical root resorption in a father and a son: a 22 year follow-up. J Periodontol 2007; 78: 367–371.

Andersson L, Bodin L, Sorensen S . Progression of root resorption following replantation of human teeth after extended extraoral storage. Endod Dent Traumatol 1989; 5: 39–47.

Andreasen J O, Paulsen H, Yu Z, Ahlquist R, Bayer T, Schwartz O . A long-term study of 370 autotransplanted premolars. Part I. Surgical procedures and standardized techniques for monitoring healing. Eur J Orthod 1990; 12: 3–13.

Andreasen J O, Paulsen H, Yu Z, Bayer T, Schwartz O . A long-term study of 370 autotransplanted premolars. Part II. Tooth survival and pulp healing subsequent to transplantation. Eur J Orthod 1990; 12: 14–24.

Andreasen J O, Paulsen H, Yu Z, Ahlquist R, Bayer T, Schwartz O . A long-term study of 370 autotransplanted premolars. Part I. Surgical procedures and standardized techniques for monitoring healing. Eur J Orthod 1990; 12: 3–13.

Andreasen J O, Paulsen H, Yu Z, Schwartz O . A long-term study of 370 autotransplanted premolars. Part III. Periodontal healing subsequent to transplantation. Eur J Orthod 1990; 12: 25–37.

Andreasen J O, Kristerson L, Tsukiboshi M, Andreasen F . Autotransplantation of teeth to the anterior region. In Andreasen J O, Andreasen F, Andersson L (eds) Textbook and colour atlas of traumatic injuries to the teeth. Copenhagen: Munksgaard, 1994.

Andreasen J O, Håkansson L . Atlas of replantation and transplantation of teeth. Michigan: W B Saunders, 1992.

Moffat M, Smart C, Fung D, Welbury R . Intentional surgical repositioning of an ankylosed permanent maxillary incisor. Dent Traumatol 2002; 18: 222–226.

Takahashi T, Takagi T, Moriyama K . Orthodontic treatment of a traumatically intruded tooth with ankylosis by traction after surgical luxation. Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthop 2005; 127: 233–241.

Filippi A, Pohl Y, von Arx T . Treatment of replacement resorption by intentional replantation, resection of the ankylosed sites, and Emdogain – results of a 6-year survey. Dent Traumatol 2006; 22: 307–311.

Sapir S, Shapira J . Decoronation for the management of an ankylosed young permanent tooth. Dent Traumatol 2008; 24: 131–135.

Steiner D . Timing of extraction of ankylosed teeth to maximize ridge development. J Endod 1997; 23: 242–245.

Tanner J M . Growth at adolescence. 2nd ed. Oxford: Blackwell Scientific Publications Ltd, 1962.

Lam R . Contour changes of the alveolar process following extractions. J Prosthet Dent 1960; 10: 25–32.

Malmgren B, Cvek M, Lundberg M, Fryholm A . Surgical treatment of ankylosed and infrapositioned reimplanted incisors in adolescents. Scand J Dent Res 1984; 92: 391–399.

Barone R, Clauser C, Grassi R, Merli M, Prato G P . A protocol for maintaining or increasing the width of masticatory mucosa around submerged implants: a 1-year prospective study on 53 patients. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent 1998; 18: 377–387.

Abrams L . Augmentation of the deformed residual edentulous ridge for fixed prostheis. Compend Contin Educ Gen Dent 1980; 1: 205–213.

Fickl S, Zuhr O, Wachtel H, Stappert C F, Stein J M, Hürzeler M B . Dimensional changes of the alveolar ridge contour after different socket preservation techniques. J Clin Periodontol 2008; 35: 906–913.

Filippi A, Pohl Y, von Arx T . Decoronation of an ankylosed tooth for preservation of alveolar bone before implant placement. Dent Traumatol 2001; 17: 93–95.

de Souza R F, Travess H, Newton T, Marchesan M A . Interventions for treating traumatised ankylosed permanent front teeth (Review). Cochrane Database Systematic Rev 2010; CD007820.

Thong Y, Messer H, Zain R, Saw L, Yoong L . Intracanal bisphosphonate does not inhibit replacement resorption associated with delayed replantation of monkey incisors. Dent Traumatol 2009; 25: 386–393.

Liewehr F R, Craft D W, Primack P D et al. Effect of bisphosphonates and gallium on dentin resorption in vitro. Endod Dent Traumatol 1995; 11: 20–26.

Levin L, Bryson E, Caplan D, Trope M . Effect of topical alendronate on root resorption of dried replanted dog teeth. Dent Traumatol 2001; 17: 120–126.

European Society of Endodontology, Quality guidelines for endodontic treatment: consensus report of the European Society of Endodontology. Int Endod J 2006; 39: 921–930.

Eliyas S, Briggs P F, Porter R W . Antimicrobial irrigants in endodontic therapy: 1. Root canal disinfection. Dent Update 2010; 37: 390–397.

Alves F R, Almeida B M, Neves M A, Moreno J O, Rôças I N, Siqueira J F Jr. Disinfecting oval-shaped root canals: effectiveness of different supplementary approaches. J Endod 2011; 37: 496–501.

Stamos D E, Stamos D G . A new treatment modality for internal resorption. J Endod 1986; 12: 315–319.

Bystrom A, Sundqvist G . Bacteriologic evaluation of the effect of 0.5 per cent sodium hypochlorite. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1983; 55: 307–312.

Bystrom A, Sundqvist G . Bacteriologic evaluation of the efficacy of mechanical root canal instrumentation in endodontic therapy. Scand J Dent Res 1981; 89: 321–328.

Sjogren U, Figdor D, Spanberg L, Sundqvist G . The antimicrobial effect of calcium hydroxide as a short-term intra canal dressing. Int Endod J 1991; 24: 119–125.

Siqueira J F Jr, Guimarães-Pinto T, Rôças I N . Effects of chemomechanical preparation with 2.5% sodium hypochlorite and intracanal medication with calcium hydroxide on cultivable bacteria in infected root canals. J Endod 2007; 33: 800–805.

Torabinejad M, Skobe Z, Trombly P, Krakow A, Gron P, Marlin J . Scanning electron microscopic study on root canal obturation using thermo-plasticised gutta-percha. J Endod 1978; 8: 245.

Gencoglu N, Yildrim T, Garip Y, Karagenc B, Yilmaz H . Effectiveness of different gutta-percha techniques when filling experimental internal resorptive cavities. Int Endod J 2008; 41: 836–842.

Main C, Mirzayan N, Shabahang S, Torabinejad M . Repair of root perforations using mineral trioxide aggregate: a long term study. J Endod 2004; 30: 80–83.

Jacobovitz M, de Lima R K . Treatment of inflammatory internal root resorption with mineral trioxide aggregate: a case report. Int Endod J 2008; 41: 905–912.

Hsien H C, Cheng Y A, Lee Y L, Lan W H, Lin C P . Repair of perforating internal resorption with mineral trioxide aggregate: a case report. J Endod 2003; 29: 538–539.

Haapasalo M, Endal U . Internal inflammatory root resorption: the unknown resorption of the tooth. Endodontic Topics 2006; 14: 60–79.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Professor Horner of the University of Manchester for his time and support drafting and reviewing the legends and text pertinent to oral and maxillofacial imaging.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed Paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Darcey, J., Qualtrough, A. Resorption: part 2. Diagnosis and management. Br Dent J 214, 493–509 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2013.482

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2013.482

This article is cited by

-

How to assess and manage external cervical resorption

British Dental Journal (2019)

-

The ins and outs of root resorption

British Dental Journal (2018)

-

Root perforations: aetiology, management strategies and outcomes. The hole truth

British Dental Journal (2016)