Key Points

-

Contains novel findings on dentists' and DCPs' perceptions of potential factors influencing the referral of patients to DCPs for fissure sealants.

-

Starts to explain how skill mix may work in dental teams and consequently, how it may be enhanced.

-

Dentists may be unaware of DCPs' scope of practice or of approaches to delegation.

-

There may be a need for enhanced undergraduate and postgraduate training.

Abstract

Objectives Little is known about the delegation of care within skill mix in dentistry, therefore this study aimed to explore dentists' and dental care professionals' (DCPs') perceptions of factors that might influence the referral of paediatric patients to dental hygienists and therapists for fissure sealants.

Method Qualitative semi-structured interviews were conducted with 10 dentists and 10 DCPs. Qualitative content analysis of the interview transcripts was used to identify themes in the data.

Results A predominant view was that there were no characteristics that systematically influenced the referral of patients to DCPs to place fissure sealants. However, idiosyncratic factors were said to occasionally play a role. Structural factors included use of resources, payment and contracting systems and practice characteristics. Individual patient-related factors were parents' and patients' attitudes and patient characteristics. Dentist-related factors included dentists' preferences, perceptions of DCPs, their perceived role of DCPs and providing a service to patients.

Conclusion This study has identified a variety of factors that may influence a dental practitioner's decision to refer child patients to DCPs for fissure sealant placement. However, these factors do not appear to be systematic.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The UK General Dental Council advises that 'Good dental care is delivered by a dental team' and requires all registrants to share their 'knowledge and skills with other team members as necessary in the interests of patients.'1

Continued changes in dentistry and oral health status have stimulated a need to review the roles of dental care professionals (DCPs) in order to deliver quality care. Recently the term 'skill mix' has been used to characterise such a mix of posts, grades or occupations in an organisation. The use of dental teams provides the potential to increase the access and efficiency of services by increasing the dental workforce and delegating tasks to specifically trained team members.2,3,4 A systematic review considered the output and cost of DCPs and estimated, very tentatively, that the addition of a dental hygienist to a single-handed dental practice increased output by 36%.5

The scope for delegation of specific tasks to team members will vary in accordance with the needs of patients. However, UK estimates suggest that 70% of all visits and 60% of all clinical time in primary care could be provided by dental therapists.6 The remainder of this paper will adopt the perspective that high quality care will see patients referred to dental therapists when this is in the best interests of the patient.

There are a number of challenges to the development of effective teams to improve healthcare quality, as quality is complex and multidimensional.7 One action proposed by Maxwell to achieve quality is the need to emphasise team, rather than individual performance.8 Thus, further research is indicated to better understand how healthcare teams work together, in order to optimise team working within dental practice.

Earlier qualitative and quantitative data imply that dentists are aware that teamwork is important, with surveys of dentists showing greater acceptance of therapists over time.9,10,11,12,13,14 Yet there has been very little research into how dentists and DCPs work together in teams, and in particular about how dentists decide on which patients to refer to DCPs for care. Greater insight into how dental teams work together might identify areas for improvement. As well as explaining the nature of skill mix in dentistry, such information might act as a basis for enhancing the role of skill mix to increase the effectiveness and efficiency of dental care.

Preventive treatment is acknowledged as being one of the important roles for dental hygienists and therapists and one specific skill expected of them is the application of fissure sealants.15 The aim of this study, therefore, was to identify factors that might influence the referral of patients from dentists to DCPs for the specific purpose of fissure sealant provision. A qualitative approach was adopted in order to uncover new areas or ideas that were not anticipated at the outset of the research.

Method

Qualitative semi-structured interviews were conducted by one investigator with 10 dentists and 10 DCPs. Recruitment was via letters to all primary care services and practitioners (dentists and DCPs) registered within a 50 mile radius of Sheffield. Purposive sampling was used to recruit participants to capture a range of experiences such as the practice setting (private or NHS), length of time qualified, role in the practice or service, age and gender. These criteria were selected because anecdotal reports have indicated that the new NHS dental contract did not encourage the use of therapists, because dentists and therapists might have different perspectives on referral patterns and because there has been a trend for greater professional acceptance of therapists.12,13,14 Sampling continued until 'saturation' when no new codes appeared in the data.16 Interviews were loosely structured and comprised open-ended questions related to the area to be explored. The original interview guide was based on preliminary discussions between researchers and primary care dentists.

Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed. The principle approach was qualitative content analysis. Data were analysed using line-by-line coding and then codes with common themes were brought together. The themes were then grouped into categories. All categories originated in the data and provided insights into, and explanations of, factors that might influence the prescribing patterns and thus success of fissure sealants. Deviant case analysis was also undertaken to ensure that any emergent explanations or theories were redefined to embrace all cases.16

The emergent categories are neither discrete nor mutually exclusive but are the constructions of the researchers to group and understand the data. Therefore, the results are presented as themes that emerged from the data rather than as coherent categories described by participants. However, quotes are used to illustrate key categories. Initials are used to anonymise the quotes.

Results

Participants demonstrated a range of perceptions as to the type of child patients that were referred by dentists to DCPs for fissure sealants. Qualitative data are primarily concerned with identifying the range of ideas and categories within the data and are not suited to describing how frequent is a particular view. However, a predominant view across most of the interviews was that there were no particular differences in the patient case-mix for fissure sealants seen by dentists or hygienists and therapists:

'They [dentists] send anybody to me, there is no boundary between what I have or have not treated.' (CT, therapist).

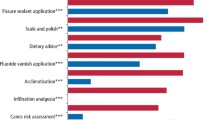

Often subsidiary to this view, several factors were mentioned that occasionally influenced treatment. These factors appeared to be idiosyncratic but could be drawn together into three categories: structural, patient and dentist-related factors (Fig. 1).

Structural factors

Three sub-categories of structural factors were identified in this category: use of resources, payments and contracting, and finally, practice or service characteristics.

Participants alluded to potential differences in referral patterns within different types of service. Notably, the referral of patients to DCPs in general dental practice was said to be influenced by the nature of the remuneration system and time pressures. Allowing DCPs to spend time on prevention was seen by some participants as enabling dentists to focus on more complex treatments. Time management and cost efficiency were therefore important considerations in the dentist's decision to refer a patient, and were therefore key sub-categories of resources. This decision, in turn, depended on the type of services in which they were working.

'In general dental practice time efficiency is important. So in simple fillings, they [dentists] have a good turn over.' (GD, dentist).

Payment and contracting were cited by both dentists and hygienists as factors in referral decisions. Employing DCPs depended on whether or not there was sufficient funding to accommodate them.

'I can't see a newly qualified DCP being able to break even, to do work under the new contract, because there is no funding for them, I think it is dependent on funding who is doing FS.' (J2D, dentist).

In contrast, some respondents expressed the view that the new NHS contract should encourage employment of DCPs. From this perspective it was felt that dentists in NHS practice may not engage fully in preventive treatments due to time considerations. Thus there were suggested benefits to employing DCPs in the practice, as they could take on more time-demanding preventive roles and release more of the dentist's time.

Several practice or service characteristics including the location and size of a practice were also said to influence the dentist's decision for referral. Practices or clinics in socio-economically deprived areas might be attended by children with high levels of caries. There might be attendant high work loads in these settings and consequently DCPs could be referred more children for caries prevention.

'...doing prevention depends on the area you work and the caries rate, I work in a high caries rate area and I do a lot of prevention.' (CT, therapist).

Individual patient factors

This section details a very variable theme in dentists' decisions for referral. Factors related to individual patients included parents' and patients' attitudes and patient characteristics such as the complexity of treatment, behaviour of the child, poor oral hygiene, socio-economic status, age and medical problems. These factors were distinct from the general 'type' of patients in a particular location, which was regarded as a structural factor.

Participants expressed a range of views about parental attitudes to DCPs. It was recognised that parents wanted the best treatment for their children and one opinion was that as long as the child was treated well, parents would not mind about the clinician's qualifications. Parental and patient attitudes were generally perceived as being positive towards DCPs. In the main, patients were reported to trust the system and, if a professional person referred their child to a DCP, they would accept that.

'I think the overall concern for parents is that the person is nice with their child.' (AD, dentist).

However, the participants did identify one parental group as being particularly concerned about the qualifications of the person providing treatment: those with negative dental experiences:

'Quite often the patients who had problems in the past, that makes them worry about the qualification of the person.' (KD, dentist).

Case complexity included different dimensions such as the volume or nature of treatment needs, poor oral health, disease levels, anxiety, medical history, age and socio-economic status of the patients.

The nature of the work referred to DCPs was described as 'simple and straightforward'. Complexity of treatment was therefore found to be an important factor in referral. Healthy patients who required routine dental care, fissure sealants, fillings or extractions in primary teeth were described as the most likely to be referred to DCPs.

'I would refer patients who were pretty immune to dental treatment, there were no particular difficulties and they have easy straight forward work like fissure sealants, simple fillings.' (OD, dentist).

Dentists' referral of anxious children varied and was described on a patient-by-patient basis. Some dentists did not refer anxious children to DCPs and used fissure sealants for them as part of their dental behaviour management strategy, in a sequence of systematic desensitisation.

'I use FS in an anxious child for acclimatisation and getting to know the child.' (JD, dentist).

Interestingly, it was mentioned that some anxious children appeared to respond better to new faces and dentists elected to refer them to DCPs for a gradual introduction to dentistry.

'If the child is difficult to manage I might refer the case to therapists for the acclimatisation and if it progresses well, they can stay with them.' (J2D, dentist).

Dentist-related factors

Dentist-related factors included dentists' perceptions of DCPs, their perceived role, dentists' preferences and providing a service to patients. Some variation in referral was linked to the quality of team working and communication abilities.

Not all dentists had complete knowledge of DCPs' training and the work that could be delegated to them. This lack of insight appeared to affect their referral decisions. Some variation in referral was linked to attitudes to DCPs in general, to the quality of team working and communication involved.

'Oh yeah, there is a law for therapists that they can place fissure sealants, hygienists I think just do scale and polishing...' (J2D, dentist).

There was also a warm appreciation among dentists for the potential support provided by DCPs, which allowed them to save time and focus on more complex treatment.

'I do think therapists are perfectly able to treat patients very well.' (AD, dentist).

There was wide variation in views on skill mix in dentistry, with a mixture of positive, ambivalent and negative comments. Potential barriers to skill mix were concerns about DCPs' clinical roles and responsibilities. Some dentists in the present study were positive about skill mix and appreciated DCPs' help and support. In contrast, other participants still thought there was a long way to go before skill mix was fully accepted in dental practice.

'Team working is good, it takes the workload off the dentists and they can do all the other things.' (OD, dentist).

The interviews did reveal some negative comments relating to DCPs' skills, professional competence of DCPs and financial matters. Indeed, the use of skill mix was found to be a perceived threat to the autonomy and standing of dentists who had studied for a long time and undertaken vocational training.

'[Dentists think] “Why should I do five years, leave college and have to have someone watch over me for a year when therapists can come out and not have any body watch over them?”' (JD, dentist).

One of the difficulties of embracing and carrying out skill mix effectively was ascribed to communication problems between dentists and DCPs. Participants believed that open communication was essential to deliver an efficient and effective service in both private and NHS settings. Furthermore, good communication ensured a shared understanding of colleagues' expectations.

'If the therapists said “Look, I'm particularly interested in difficult children”, I would refer them.' (OD, dentist).

Dentists were found to have a range of personal preferences which came into play in their decision to refer or not refer a child to a DCP for fissure sealants. However, despite repeated and direct questioning and interpretation, no specific pattern was apparent for dentists' personal preferences. Preferences seemed to be quirks of different individuals. Some dentists preferred to refer children for fissure sealants whereas others were happy to see the children and place their fissure sealants.

'I always do most of fissure sealants myself because I like doing the work.' (AD, dentist).

Interaction between the themes

There were a small number of interactions between these themes and the categories were not discrete. For example, there was a possible interaction between payment and contracting and dentists' preference.

'I still think that the new contract won't change the dentists who was never giving preventative advice, they are some dentists who are always doing it and I'm sure they are still doing it.' (AD, dentist).

Likewise, efficient use of time through the use of skill mix could interact with service to patients. For example, some dentists still opted to place fissure sealants themselves, despite acknowledged time constraints. In some cases there was also the consideration of not inconveniencing the patient with an extra visit (service to patient).

'I get directly involved when I do a regular check up, it may not be a particularly good use of my time but it is difficult to ask the patients to come back and see the other member of the staff to place fissure sealant.' (TD, dentist).

Discussion

This is the first study to explore dentists' and DCPs' perceptions about dentists' decision-making in the referral of patients to DCPs for specific items of treatment. A common finding in the data was that there were no factors that systematically influenced referral. However, a series of structural, patient-related and dentist-related factors were identified that might have some influence on the effectiveness and acceptance of team working and skill mix in dentistry.

In this study, the referral of patients to DCPs was found to be influenced by different financial situations, time pressures, payments, contracting systems and finally, practice or service characteristics. It was suggested that some dentists perceive DCPs to be less time-pressured, and are therefore happy to delegate dental prevention work to them. This finding is compatible with earlier research on dentists' views about DCPs delivering health interventions.9 In that study participants were keen to delegate preventive work to DCPs, whereas others merely wanted to pass on unrewarding tasks.

The findings from the systematic review and other quantitative studies that considered the productivity of DCPs triangulated with the results of our qualitative study, in that cost efficiency was mentioned as one of the key reasons influencing the use of skill mix in dentistry.5,13 However, dentists may be discouraged from making greater use of skill mix if they must incur the greater costs of employing a DCP, but are not rewarded adequately for the greater output. These data reveal that some dentists believe that the remuneration for the work done by DCPs does not offset the additional cost of employing one. Such dentists may need greater encouragement to do so.

There is a paucity of data on patient preferences and attitudes with respect to their acceptance of treatment provision by DCPs. Participants in the present study suggested that parental attitude was a possible factor considered by dentists when referring young patients to a DCP. Dyer and Robinson have studied the patient acceptability of treatment by DCPs.17,18 Approximately 60% were willing to receive simple restorative treatment from a therapist, with acceptability predicted by being younger and having a perceived need for treatment. Fewer (approximately 50%) were willing to allow a therapist to restore a child's tooth. They recommended that both government and dentists could be involved in promoting greater use of skill-mix to the public and patients. Gallagher and Wright have suggested that dentists' attitudes towards DCPs may have an impact on patient satisfaction with DCP-provided care.12

One participant felt that negative dental experiences might influence parental acceptance of treatment by DCPs. In a study of 1,000 adults across the UK, participant dental anxiety, as measured by the modified dental anxiety scale, was unrelated to their willingness to accept dental treatment from a therapist for themselves or a child.18

At least one dentist working with a DCP in this study was not completely aware of the range of duties that DCP might undertake. This observation may need further quantitative exploration. It may be that future education of qualified and undergraduate dentists is required if skill mix is to be further employed in dentistry.

One dentist in this study commented that dentists (unlike DCPs) took part in vocational training. This difference between dentists and hygienists and therapists is now decreasing with the introduction of pilot vocational training schemes for hygienists and therapists.

The potential role played by DCPs in caries prevention is acknowledged in these data and is supported by both policy and previous studies.13,14,15 The present study further demonstrated this belief through an in-depth qualitative enquiry. It was encouraging that participants frequently voiced their opinion that the role of DCPs in caries prevention was equally as important as the role of dentists in this respect.

As with all research, these data should be interpreted with care. The aim was to identify factors that might influence the referral of patients from dentists to hygienists or therapists. Dentists who did not work with these classes of DCPs could not refer to them, and consequently they were excluded from the study. It is possible that such dentists would have different views on the role of DCPs. The data can therefore only be applied to dentists who work with hygienists and therapists. The data do indicate a range of views on the referral of patients however, and saturation occurred so that no new themes emerged during the latter interviews, suggesting theoretical representation.

One other methodological matter that may have influenced the findings relates to acceptability bias. Participants were recruited to a study on referral of patients for fissure sealants and may have ascertained that the researchers supported this practice. They may therefore have provided views that were more positive about the use of skill mix. Nonetheless, participants did make some negative comments about aspects of work with DCPs.

In conclusion, this study has identified that a variety of factors may influence the use of skill mix and dentists' decisions to refer patients to DCPs for fissure sealant placement. Quantitative research would reveal the extent of factors influencing the use of skill mix in dentistry. However, greater use of skill mix might be encouraged by appealing to the 'business instincts' of dentists and by promoting the public acceptability of treatment by DCPs. Dentists' knowledge of the roles of DCPs might need to be assessed to see if dentists need further education in this important area.

References

General Dental Council. Principles of dental team working. London: General Dental Council, 2005.

World Health Organization. Report of an expert committee on auxiliary dental personnel. Tech Rep Series No. 163. Geneva: WHO, 1959.

Department of Health. Modernising NHS dentistry - implementing the plan. London: The Stationery Office, 2000.

Department of Health. NHS dentistry: options for change. London: The Stationery Office, 2002.

Galloway J, Gorham J, Lambert M, Richards D, Russell D, Welshman J. The professionals complementary to dentistry: a systematic review and synthesis. London: UCL Eastman Dental Hospital Dental Team Studies Unit, 2003.

Evans C, Chestnutt, I G, Chadwick B L. The potential delegation of clinical care in dental practice. Br Dent J 2007; 203: 695–699.

Donabedian A. The definition of quality and approaches to its assessment. Explorations in quality assessment and monitoring, volume 1. Chicago: Health Administration Press, 1980.

Maxwell R. Quality assessment in health. BMJ 1984; 288: 1470–1472.

Dyer T, Robinson P . General health promotion in general dental practice - the involvement of the dental team. Part 2: a qualitative and quantitative investigation of the views of practice principals in South Yorkshire. Br Dent J 2006; 201: 46–51.

Scheffler R M, Kushman J E . A production function for dental services: estimation and economic implications. Southern Econ J 1977; 44: 25–35.

Kushman J E, Scheffler R M, Miners L, Mueller C . Non-solo dental practice: incentives and returns to size. J Econ Bus 1978; 31: 29–39.

Gallagher J, Wright D A . General dental practitioners' knowledge of and attitudes towards the employment of dental therapists in general practice. Br Dent J 2003; 194: 37–41.

Harris R, Burnside G . The role of dental therapists working in four personal dental service pilots: type of patients seen, work undertaken and cost-effectiveness within the context of the dental practice. Br Dent J 2004; 197: 491–496.

Ross M K, Ibbetson R J, Turner S. The acceptability of dually-qualified dental hygienist-therapists to general dental practitioners in South-East Scotland. Br Dent J 2007; 202: E8.

General Dental Council. Scope of practice. London: General Dental Council, 2009.

Pope C, Mays N. Qualitative research in health care. London: BMJ Publishing, 2000.

Dyer T, Robinson P G. Public awareness and social acceptability of dental therapists. Int J Dent Hyg 2009; 7: 108–114.

Dyer T A, Humphris G, Robinson P G. Public awareness and social acceptability of dental therapists in the UK. Br Dent J in press.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Nilchian, F., Rodd, H. & Robinson, P. Influences on dentists' decisions to refer paediatric patients to dental hygienists and therapists for fissure sealants: a qualitative approach. Br Dent J 207, E13 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2009.856

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2009.856

This article is cited by

-

Dental skill mix: a cross-sectional analysis of delegation practices between dental and dental hygiene-therapy students involved in team training in the South of England

Human Resources for Health (2014)

-

Supporting newly qualified dental therapists into practice: a longitudinal evaluation of a foundation training scheme for dental therapists (TFT)

British Dental Journal (2013)

-

An evaluation of a vocational training scheme for dental therapists (TVT)

British Dental Journal (2010)