Key Points

-

This paper summarises demographic details of the specialist orthodontic workforce in the United Kingdom.

-

Particular emphasis is placed on changes in the gender and ethnic balance of the specialist workforce.

-

Reasons for changes are suggested, together with implications for workforce planners.

Abstract

Objective To describe the gender and ethnic trends of the United Kingdom orthodontic workforce.

Design and setting A cross-sectional survey using a postal questionnaire to specialist orthodontic practitioners in the United Kingdom (2006-2007).

Subjects All those on the Specialist List in Orthodontics held by the General Dental Council in October 2006.

Materials and methods The data collected using the questionnaire included demographic details (gender, ethnicity, current age, place of birth), undergraduate and postgraduate dental schools attended, calendar years in which professional qualifications were achieved, anticipated year of retirement and geographical location of work place.

Results The response rate was 81.5%. There are more male (60.2%) than female (39.8%) orthodontists presently working in the United Kingdom. Minority ethnic groups are better represented amongst the orthodontic workforce than they are in the general population, however their distribution throughout the United Kingdom is uneven. The trends in the results indicate that the gender and ethnic balance of the specialist orthodontic workforce has been changing and the proportion of females and those from non-white ethnic groups has increased. In contrast, the majority of those retiring over the next few years will be white males (60%).

Conclusion This study suggests that there will be greater ethnic diversity and more female orthodontists in the future workforce. Consequently, working patterns should be kept under regular review so that an optimal orthodontic service can be maintained in the United Kingdom.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Planning future workforce requirements is a notoriously difficult process to undertake, particularly as there continues to be a need1 and growing demand for orthodontic treatment within the United Kingdom. The ability to provide an optimal orthodontic service may be affected if there is an insufficient supply of appropriate workforce personnel. In recent years, some changes have been reported in the demographics of the dental2,3,4 and orthodontic5 workforces which may be of significance to workforce planners.

The proportion of registered female dentists in the United Kingdom has increased.6 In 2006, 37% of those on the Specialist List in Orthodontics held by the General Dental Council were female.6 This is a similar proportion to workforce reports from other countries within the European Union.7 However, it appears further changes are likely, as 66% of those currently in orthodontic training posts are female.5

Numerous studies have indicated that differences can exist in the working patterns of male and female dental practitioners8,9,10,11 and it is generally accepted that greater proportions of females work part-time8,9,10 and take career breaks.10,11 The most recent United Kingdom workforce report suggested that a 'feminisation' of orthodontic specialists was occuring.5 Therefore, in light of current understanding of working patterns, future workforce planning may be affected.

In the last few years it has also become apparent that the proportion of those from minority ethnic groups either applying, in training or practising, both dentistry and orthodontics, has increased.4,12,13,14,15 Despite this, little is known as to whether the cultures and traditions of minority ethnic groups affect the supply of orthodontic personnel.12,16

The aims of this study were to examine the demographics of the current specialist orthodontic workforce and explore any trends which may exist in the gender and ethnic balance of those on the Specialist List in Orthodontics.

Materials and methods

Ethical approval was granted for this research from the Joint Research and Ethics Committee of the University College London/University College London Hospitals (reference 06/Q0505/17).

Target population

The target population for this study was the 1,155 registrants on the Specialist List in Orthodontics held by the General Dental Council on the 31 October 2006.6 There were a number of registrants whose addresses were outside the United Kingdom. For the purposes of this study, all those with overseas addresses were excluded and this resulted in a final target population of 1,088 registrants.

Questionnaire development

A pilot questionnaire developed by the research team was circulated to 32 orthodontists (94% response rate) of various grades and geographic locations. This allowed the questionnaire to be assessed for acceptability, validity, question relevance and error. Subsequent to the pilot study, some minor amendments were made and the final questionnaire was produced. The data collected using the questionnaire included:

-

1

Demographic details: gender, ethnicity, place of birth and current age

-

2

Undergraduate and postgraduate dental school attended and calendar years in which professional qualifications were achieved

-

3

Anticipated year of retirement

-

4

Geographical location of work place.

Postal method

For the main study, each subject received a cover letter, a questionnaire and a stamped addressed return envelope in November 2006. In order to maximise the response rate, principles of the Tailored Design Method17 were applied where possible. An identical second, and subsequently third, mailing in January and February 2007 was sent to all non-respondents.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarise the demographics of respondents and logistic regression was used to illustrate year-on-year changes in the gender and ethnicity of newly qualified dental practitioners who went on to undertake further specialist training in orthodontics. Statistical analysis was carried out using SPSS version 14.0 for Windows18 and Stata Version 9.2.19 ArcView GIS 3.220 geographical mapping software was used to construct the thematic map shown in Figure 3.

Results

Response to the questionnaire

Of the 1,088 orthodontists surveyed, 887 returned completed questionnaires, giving an overall response rate of 81.5%. No response bias could be detected in relation to gender and year of undergraduate qualification of respondents and non-respondents. The majority of respondents answered all questions, but in some cases, due to no response being given to some questions, the total number of responses in any section was less than the total number of questionnaires returned.

Demographics of respondents

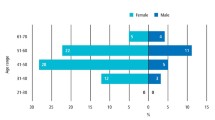

Sixty percent of respondents were male and the mean age of respondents was 46.12 (SD 9.91) years. The population pyramid usefully illustrates the difference in ages of males and females (Fig. 1). There were more males than females recorded in every age band over the age of 40 years, while there were more females in the younger age bands.

Most respondents described their ethnicity as white British (71.4%) (Table 1). The population pyramids in Figure 2 demonstrate that there was a greater frequency of younger orthodontists in the non-white ethnic groups and marginally more females than males. However, the opposite was true in the white group, where there was a greater frequency of older orthodontists and more males than females. On the other hand, there were more white female orthodontists than their male counterparts in the younger age groups.

The geographical distribution of specialist practitioners in terms of ethnicity (white and non-white) and gender is displayed in Figure 3. Respondents were mapped according to the location of their principal place of work and were categorised under the ten strategic health authorities (SHAs) in England and by country for Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. Strategic health authorities were chosen as they are responsible for developing and improving local health services, but they also provide a useful platform for future research. It was only in the London region that there was an almost equal representation of each gender and ethnic group (male and female, white and non-white). There appeared to be equal proportions of white males and females in Scotland, the East Midlands, the South East and South West England, but a greater proportion of white males in almost every other region examined. The map also illustrated that there was a greater concentration of those from non-white ethnic groups working in the South of England than in the rest of the United Kingdom.

Gender and ethnic trends in the orthodontic workforce

In order to examine any demographic trends amongst respondents, logistic regression analysis was conducted which showed the year-on-year changes in gender across the orthodontic workforce by examining the year of undergraduate qualification. The year of undergraduate qualification was chosen as this information was supplied by the majority of respondents and was stable. The results show that the probability of being a newly qualified female dental graduate increased by 6% each year from 1953 to 2000 and this trend was highly statistically significant (OR = 1.06, CI = 1.04-1.08, p <0.001) (Fig. 4).

A similar analysis was conducted examining the year-on-year changes in ethnicity (Fig. 5). The results show that the odds of being a white British graduate decreased by 7.5% each year from 1953 to 2000 (OR = 0.93, CI = 0.91-0.94, p <0.001), while the odds of being a dental graduate from a South Asian or 'Other' ethnic group increased each year by 14% and 5%, respectively (OR = 1.14, CI = 1.10-1.18, p <0.001; OR = 1.05, CI = 1.03-1.07, p <0.001). No statistically significant trend could be detected amongst white Irish graduates and this may possibly be explained by the small numbers involved (OR = 1.03, CI = 0.99-1.06, p = 0.157).

In addition, the gender and ethnic trends were examined together and showed that the probability of being a white female dental graduate increased by 2.5% each year from 1953 to 2000 (p = 0.001), whilst the probability of being a white male graduate decreased by 8% each year (p <0.001). The probability of being a non-white female or male dental graduate increased by 12% and 5% respectively each year (both p <0.001) (Table 2 and Fig. 6).

Current geographical location compared with place of birth, undergraduate and postgraduate study

Almost a quarter of respondents worked in the same SHA/region as where they were born (Table 3). A connection was also demonstrated between places of education, as almost half of respondents studied in the same SHA/region for their undergraduate and postgraduate qualifications and approximately one third are currently working in the same SHA/region as where they completed either their undergraduate or postgraduate study.

Retirement

It was found that just over 15% of respondents plan to retire from the NHS in the next five years and almost two thirds of this group are white males (Table 4). Almost a third of respondents will have retired from NHS practice in ten years time and more than half of this group will be white males.

Discussion

Gender trends

Whilst currently there are more male than female orthodontists working in the United Kingdom, it is clear that this is changing and the trends demonstrated in Figure 4 seem likely to continue. It is recognised that females now make up a greater proportion of the orthodontic postgraduate student body than males.5 However, it is yet to be seen whether more females will choose the flexibility of specialist practice over a hospital career upon qualification. Interestingly, the British Orthodontic Society Training Grades Group database shows there are currently more female than male fixed-term training appointments (FTTAs) in employment across the United Kingdom.21

Previous studies have highlighted that only a small difference exists in the working patterns of male and female orthodontists,5,7,22 although there were some differences in their output per session.5,22 It is well established that various factors, such as having children, can affect the working patterns of dental practitioners.8,9,10 However, it is unclear whether the working patterns of dental practitioners and specialist orthodontists are always comparable and some researchers have commented that female specialists may be less likely to take time away from work than their colleagues in general practice.5,22

Therefore, as more females enter the workforce, it would be prudent to investigate the effect of career breaks and family size on the working patterns of specialists, as the findings of this study imply that in time there may be more female orthodontists than male.

Ethnic trends

The proportion of respondents from non-white minority ethnic groups (15.7%), particularly the Asian Indian group, was greater than the average in the United Kingdom general population (7.9%).23 However, this has not always been the case and the ethnic make-up of the specialist orthodontic workforce is seen to have changed considerably over the last forty years (Figs 5 and 6). In the 1950s the profession was dominated by those of white British ethnic origin. However, since the 1960s there has been a steady increase in those of South Asian ethnic origin (Indian, Pakistani or Bangladeshi backgrounds) and in the mid-1970s those from 'Other' ethnic groups.

Migration from the Commonwealth to the United Kingdom largely started in the 1950s and has continued to some extent ever since.24 In 1972 the United Kingdom joined the European Union, which has since given greater freedom of movement between the member states24 and this may help to explain the increase in 'Other' ethnic groups amongst the United Kingdom population. Although these historical events may partly explain the ethnic diversity of the workforce, they do not explain how the proportion of white male orthodontists has decreased, and the proportion of South Asian orthodontists has increased, above the proportions in the general population.

Previous research has shown that a greater proportion of those from minority ethnic groups than in the general population apply to undergraduate dental courses.12,13 Equally it is acknowledged that the family unit of those from minority ethnic groups plays an important role in guiding career choice.25 A recent report indicated that South Asian parents are encouraging their daughters to obtain professional qualifications at university and reported that dentistry was a key area where proportionally more South Asian females submit successful applications than white females.26 There is also a greater probability that following undergraduate education, those from minority ethnic groups will pursue additional postgraduate education and training.25 These factors combined may help explain why South Asians, in particular, are more likely to enter professions such as dentistry and pursue postgraduate orthodontic training. It is, however, unknown whether changes in the ethnic balance will affect workforce availability, although it has previously been suggested that this may be the case.27 This is an area which requires further research.

All the evidence does seem to support the hypothesis that the trends displayed in Figures 5 and 6 are likely to continue. The majority of non-white orthodontists are in the younger age bands, while white males dominate the older age bands (Fig. 2). Therefore, as the workforce begins to age and the older white males retire, there will be an increase in the proportion of females and those from non-white ethnic groups.

This study provides further confirmation that there is a link between place of birth, undergraduate and postgraduate study and current place of work.28 However, as the demographics of the workforce change, the migration of workers throughout the United Kingdom may also change. The 2001 population census found that minority ethnic groups tend to live in the main cities and almost half of the entire population of minority ethnic groups was based in London,29 thus the findings of Figure 3 are perhaps not surprising. In addition, it is acknowledged that those of South Asian ethnic background, particularly females,26 may be more likely to live at home during their university education30 and thus perhaps work eventually in the same region, although with the increased cost of living the same can be said for all school leavers and in 2007 nearly one third planned to live at home during their university years.31 However, a more recent study has indicated that this figure may actually be much higher.30 Therefore, the significant regional variation in orthodontic service provision which already exists22 may be further exacerbated by any continued changes in the workforce demographics.

Conclusion

This study suggests that there will be greater ethnic diversity and more females in the future orthodontic workforce. Accordingly, current and anticipated working patterns require further consideration to ensure that an optimal orthodontic service can be maintained in the United Kingdom.

References

Nuttall N, Harker R . Impact of oral health. Children's dental health in the United Kingdom 2003. London: The Stationery Office, 2004. ISBN 0 11 621268 3. http://www.statistics.gov.uk/downloads/cdh5_Impact_of_oral_health.pdf (accessed 12 March 2008).

Universities and Colleges Admissions Service. Qualifications/Subject datasets 2000-2006. Available from http://www.ucas.com/about_us/stat_services/stats_online/annual_datasets_to_download/

Duguid R, Drummond J R . The admission of students to UK dental schools – recent trends (1983-1998). Eur J Dent Educ 2000; 4: 71–76.

Newton N T, Gibbons D E . The ethnicity of dental practitioners in the United Kingdom. Int Dent J 2001; 51: 49–51.

Murphy T C, Parkin N A, Willmot D R, Robinson P G . The feminisation of the orthodontic workforce. Br Dent J 2006; 201: 355–357.

General Dental Council. The dentists register. London: General Dental Council, 2006.

McGuinness N, Collins M . The orthodontic workforce in Ireland: a report by the Orthodontic Society of Ireland. J Ir Dent Assoc 2007; 53: 142–144.

Brennan D S, Spencer A J . Differences in time devoted to practice by male and female dentists. Br Dent J 1992; 172: 348–349.

Matthews R W, Scully C . Working patterns of male and female dentists in the UK. Br Dent J 1994; 176: 463–466.

Newton J T, Thorogood N, Gibbons D E . The work patterns of male and female dental practitioners in the United Kingdom. Int Dent J 2000; 50: 61–68.

Newton J T, Buck D, Gibbons D E . Workforce planning in dentistry: the impact of shorter and more varied career patterns. Community Dent Health 2001; 18: 236–241.

Bedi R, Gilthorpe M S . Ethnic and gender variations in university applicants to United Kingdom medical and dental schools. Br Dent J 2000; 189: 212–215.

Stewart F M J, Drummond J R, Carson L, Hoad Reddick G . The future of the profession – a survey of dental school applicants. Br Dent J 2004; 197: 569–573.

Gallagher J E, Patel R, Donaldson N, Wilson N . The emerging dental workforce: why dentistry? A quantitative study of final year dental students' views on their professional career. BMC Oral Health 2007; 7: 7. DOI: 10.1186/1472-6831-7-7.

Drugan C S, Chestnutt I G, Boyles J R . The current working patterns and career aspirations of specialist trainees in dentistry. Br Dent J 2004; 196: 761–765.

Newton J T, Thorogood N, Gibbons D E . A study of the career development of male and female dental practitioners. Br Dent J 2000; 188: 90–94.

Dillman D A . Part one. Elements of the tailored design method. In Mail and internet surveys: the tailored design method. 2nd ed. pp 3–214. New York: John Wiley and Sons, 2000.

SPSS Version 14.0. SPSS UK Ltd, 2005. 1st Floor, St Andrew's House, West Street, Woking Surrey, GU21 1EP.

Stata Version 9.2. College Station, Texas, 77845, USA, 2007.

ArcView GIS 3.2. Environmental Systems Research Institute, Inc., 1999.

British Orthodontic Society. Personal communication with Miss C. O'Brien, Secretary of Training Grades Group, April 2007.

Robinson P G, Willmot D R, Parkin N A, Hall A C . Report of the Orthodontic Workforce Survey of the United Kingdom February 2005. Sheffield: Department of Oral Health and Development, School of Clinical Dentistry, The University of Sheffield, 2005. http://www.bos.org.uk/publicationslinks/workforcesurvey.htm

Office for National Statistics. United Kingdom 2001 census. Ethnicity and identity: population size webpage. London: Office for National Statistics, 2004. http://www.statistics.gov.uk/cci/nugget.asp?id=455 (accessed 12 March 2008).

Migration Watch UK . The history of migration to the UK. Guildford: Migration Watch UK, 2006, Briefing Paper 6.1. http://www.migrationwatchuk.com/Briefingpapers/history/history.asp (accessed 12 March 2008).

Connor H, Tyers C, Modood T, Hillage J . Why the difference? A closer look at higher education minority ethnic students and graduates. London: Department for Education and Skills, 2004. Research report no. RR552. http://www.dfes.gov.uk/research/data/uploadfiles/RR552.pdf (accessed 12 March 2008).

Bagguley P, Hussain Y . The role of higher education in providing opportunities for South Asian women. Bristol: Joseph Rowntree Foundation/The Policy Press, 2007. http://www.jrf.org.uk/bookshop/eBooks/1997-education-ethnicity-poverty.pdf (accessed 12 March 2008).

Newton J T . Career hopes of dental school applicants. Br Dent J 2005; 198: 697.

O'Brien K D, Roberts C . An analysis of the effects of place of childhood, undergraduate and postgraduate education upon the regional distribution of specialist orthodontic practitioners. Br Dent J 1991; 171: 280–282.

Office for National Statistics. United Kingdom 2001 census. Ethnicity: regional distribution webpage. London: Office for National Statistics, 2003. http://www.statistics.gov.uk/cci/nugget.asp?id=263 (accessed 12 March 2008).

Davies P, Slack K, Hughes A, Mangan J, Vigurs K . Knowing where to study? Fees, bursaries and fair access. The Sutton Trust/Staffordshire University, 2008. http://www.suttontrust.com/reports/StaffordshireReportFinal.pdf (accessed 12 March 2008).

Anon. Third of students to live at home. BBC News website 2007 July 18. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/education/6903236.stm (accessed 12 March 2008).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Collins, J., Hunt, N., Moles, D. et al. Changes in the gender and ethnic balance of the United Kingdom orthodontic workforce. Br Dent J 205, E12 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2008.839

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2008.839

This article is cited by

-

High job satisfaction among orthodontic therapists: a UK workforce survey

British Dental Journal (2018)

-

High job satisfaction among orthodontic therapists

BDJ Team (2018)

-

Career satisfaction and work-life balance of specialist orthodontists within the UK/ROI

British Dental Journal (2017)

-

Orthodontist wins award

British Dental Journal (2010)

-

Factors which influence working patterns of orthodontists in the United Kingdom

British Dental Journal (2009)