Abstract

Study design:

An observational study.

Objective:

To develop a self-administered tool for assessment of sacral sparing after spinal cord injury (SCI) and to test its validity in individuals with SCI.

Setting:

Peking University Third Hospital, Beijing, China.

Methods:

A 5-item SCI sacral sparing self-report questionnaire was developed based on several events that most patients might experience during bowel routine. 102 participants who sustained SCI within 12 months were asked to complete the questionnaire followed by an anorectal examination. Agreements of answers to the questionnaire and the physical examination were analyzed. Sensitivity, specificity and Youden's index of each item was calculated.

Results:

The first four questions regarding the S4-5 sensation including deep anal pressure showed high agreement with the results of the physical examination (κ: 0.79–0.93). Sensitivity, specificity and Youden's index were also high (all above 80%). For the fifth question related to the voluntary anal contraction, the agreement was almost perfect with good sensitivity and specificity among patients without increased anal sphincter tone (AST). In patients with increased AST, the agreement was fair.

Conclusion:

The validity of this questionnaire for the assessment of sacral sparing in up to 12 months post injury is good except for the motor function when there was increased AST. In some situations it could be considered as an alternative tool for digital rectal examination, especially when repeated examinations are not feasible. It is suggested that change of sacral sparing may be detected by the questionnaire.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The International Standards for Neurological Classification of Spinal Cord Injury (ISNCSCI) is now widely accepted as the gold standard for the assessment and characterization of neurological function after spinal cord injury (SCI). Based on a standardized sensory, motor and anorectal examination, the testing scores within the ISNCSCI worksheet are documented, and then the neurological level of injury (NLI) and the American Spinal Injury Association (ASIA) Impairment Scale (AIS) can be calculated. The AIS designates the degree of impairment from A to E.1

The ISNCSCI examination including AIS should be performed within 72 h of admission and discharge whenever possible,2 as well as during routine follow up throughout the patient’s lifetime. This is essential because the severity of injury may change over time post injury as a result of, for example, post-traumatic syringomyelia or clinical interventions.3 Thus, it is important to promptly detect any improvement or deterioration of the neurological impairment4, 5 or any possible effects of clinical care both in the acute phase after injury and during the long-term follow up.5, 6 Besides, monitoring the neurological level of injury and the AIS grade will also support clinical research and provide better understanding regarding the pathophysiology following SCI.6

Among the evaluations to be performed when classifying SCI using the ISNCSCI, sacral sparing is the most important component to distinguish a complete injury (AIS A) from an incomplete one (AIS B/C/D), as well as a sensory incomplete injury (AIS B) from a motor incomplete one (AIS C/D).1 The definition of sacral sparing was first introduced as a criterion of classification in the 1992 revision of ISNCSCI.7 Since then, this concept has remained an important concept in the following ISNCSCI updates.8 Furthermore, recently the value of sacral sparing as indicator for the prognosis of newly injured persons was reported.9 Therefore, it is obviously that sacral sparing testing should not be neglected at any ISNCSCI assessments.

Typically, the examination of sacral sparing including digital rectal examination should be conducted by health care professionals who have received standardized training on ISNCSCI.10 However, it is not always easy to get access to the anorectal area for examination at the acute settings.11 Meanwhile, for many of the patients with SCI who need regular assessments according to ISNCSCI, multiple visits to the clinic are not feasible for several reasons, such as poor economic conditions, long distance transportation and so on. In addition, some patients may not be willing to undergo repeated digital rectal examinations because of the uncomfortable feeling and associated risks such as rectal bleeding and undesired bowel motion.12

A few researches have made successful attempts to find alternative ways for examination or prediction of sacral sparing. Zariffa et al.13 reported a close relationship between functional sparing at S1 and S4-5 segments that may help estimate AIS grades when a complete examination of sacral sparing (S3-5) is not available. Marino et al.11 found that the pressure sensation at S3 dermatome showed a substantial agreement with deep anal pressure (DAP) in persons with supraconal SCI, suggesting S3 pressure as an alternative to a full sensory sacral sparing test. At the present time, these evaluations are still expected to be carried out by clinicians. Hence, it is proposed that a self-administered test for sacral sparing should have the following benefits: (1) easier and more acceptable for the patients, (2) require fewer resources, (3) provide faster data collection and (4) changes can be reported more readily as the procedures are performed regularly. Harvey et al.12 reported an approach of using self-report to determine S4-5 sensory and motor function. Patients with SCI for more than 1 year attending a SCI outpatient clinic were asked four questions regarding the sensation of light touch (LT), pinprick (PP), DAP and the voluntary anal contraction (VAC). The diagnostic accuracy was reasonably good, although a relatively high rate of false-positive responses was found in patients with lower level of injury.

However, there is need to further explore the feasibility of using self-assessment for the sacral sparing determination within the acute phase and the first year post injury. Furthermore, it could be easier for the patients to understand and perform if the questions are coupled to activities experienced during their regular bowel routine. This study aimed at developing and validating a bowel-routine-based self-report questionnaire for assessment of sacral sparing after SCI. The agreements of answers to the questionnaire and the health professional performed anorectal examination were tested.

Patients and methods

Participants

A total of 102 consecutive patients with SCI, aged over 18 years, who were admitted to the Department of Rehabilitation Medicine, Peking University Third Hospital were included. Patients were excluded if they had neurologic impairments unrelated to SCI, such as peripheral nerve injury, brain injury and cognitive deficits, or if they were unable to complete the questionnaire. Informed consent was obtained from each participant, and the study protocol was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Board of Peking University Third Hospital.

Questionnaire

A SCI sacral sparing self-report questionnaire (Appendix 1) was developed based on events that most patients experience during their regular bowel routine. Five questions were included in the questionnaire. Q1 (perceiving the tissue) and Q2 (identifying the water temperature as warm or cold) were designed for the evaluation of sensation at S4-5 dermatome, Q3 (perceiving the inserted finger) and Q4 (perceiving the inserted enema tube) for testing of the DAP, and Q5 (holding the enema for more than 1 minute) for evaluation of the VAC. Three options were offered for each question: Yes, No and not applicable (NA), and only one of them could be chosen.

Procedures

Within 1 week after admission, each participant was asked to complete the self-report questionnaire based on their perceptions during the bowel routine, no matter whether the tasks were performed by themselves or with assistance from others. Then on the same day, the ISNCSCI examination was performed by an attending physician who had received standardized training for the examination. The following items were recorded specifically for this study: sensation at S4-5 dermatome (S4-5 sensation, ‘preserved’ or ‘absent’), DAP (‘preserved’ or ‘absent’), VAC (‘preserved’ or ‘absent’) and anal sphincter tone (AST) (‘increased’ or ‘not increased’). For the S4-5 sensation, any sensory preservation at this level is considered as the evidence of sensory incompleteness. Therefore presence of either LT or PP at either side of S4-5 dermatome was recorded as ‘preserved’, regardless of whichever side or whether the sensation is normal or altered. A record of ‘absent’ only occurred when both LT and PP were lost on both sides.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 20.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Consistency test (κ coefficient) was performed between the following items: S4-5 sensation and Q1, S4-5 sensation and Q2, DAP and Q3, DAP and Q4, and VAC and Q5, respectively. In order to detect the possible influence of increased AST on Q5, consistency tests between Q5 and VAC was further performed in subgroups with or without increased AST, separately. Data collected from participants who sustained SCI <1 month (acute phase) or 1–12 months (post-acute phase) were further analyzed separately. Sensitivity, specificity and Youden's index of each question was calculated. Samples reporting ‘NA’ for any question were excluded from the analysis related to that specific question. κ-value was interpreted according to the following criteria:14 0 as poor; 0.01 to 0.20 as slight; 0.21 to 0.40 as fair; 0.41 to 0.60 as moderate; 0.61 to 0.80 as substantial; and 0.81 to 1.00 as almost perfect. Significance was set at the P<0.05 level.

Results

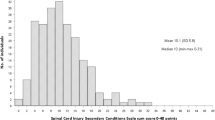

A total of 102 participants were included in this study. The standardized demographic characteristics, neurological level of injury and AIS of the study population are shown in Table 1. The median age was 46.0 years. The most common etiology is falls, followed by transport. The majority of individuals had cervical SCI (56%). Among the participants, 31 (30%) suffered a complete injury, whereas 71 (70%) individuals suffered an incomplete injury.

Table 2 shows the level of agreement between S4-5 sensation and Q1 and Q2, respectively. All participants had the experience of using tissue after defecation and accordingly chose ‘Yes’ or ‘No’ for Q1 (n=102), while one participant reported ‘NA’ for Q2 (n=101). Both κ coefficients are statistically significant, although the consistency of S4-5 sensation and Q1 (κ=0.91, almost perfect) is better than S4-5 sensation and Q2 (κ=0.79, substantial).

Consistencies between DAP and Q3 and Q4, respectively, are shown in Table 3. Only 89 out of 102 participants had the experience of digital evacuation (n=89 for Q3) while all of them had used enema at least once (n=102 for Q4). Both κ coefficients are statistically significant and reach almost perfect level (0.93 and 0.93, respectively), indicating that the agreement between Q3 and Q4 and DAP is excellent.

Level of agreement between VAC and Q5 (n=102) shown in Table 4, is substantial (κ=0.70, P<0.05). Table 5 further shows the results when considering the influence of AST. Among the participants, 24 were found with increased AST, while the other 78 participants were not. For the subgroup with increased AST, agreement was fair (κ=0.21) and not significant (P=0.09), while agreement in the subgroup without increased AST was almost perfect (κ=0.89) and significant.

When data from the acute (n=51) and the post-acute (n=51) phase groups were analyzed separately, the results of consistency test were similar to what was found from the whole group (n=102, Table 6). While accuracy of Q1-Q4 regarding sensory sacral sparing was good, the accuracy of Q5 regarding the motor sparing depended on the AST. The consistency between Q5 and VAC was fair in those with increased AST in the post-acute phase. Seven out of 51 participants in the acute phase presented with increased AST, and all of them reported ‘Yes’ for Q5 despite of the absence of VAC (false-positive response), making it impossible to calculate the κ coefficient. In those without increased AST, substantial to almost perfect consistency of Q5 with VAC was found in both acute and post-acute phase groups.

Sensitivity, specificity and Youden's index of each item are listed in Table 7. Both Q1 and Q2 show sensitivity and specificity of more than 90% for detecting the S4-5 sensation. Youden's index of Q1 (0.90) is higher than that of Q2 (0.83). Similarly was found for Q3 and Q4, each with very high sensitivity and specificity for detection of DAP independently and a higher Youden's index for Q4 (0.96) than for Q3 (0.92). For Q5, both the sensitivity and specificity of detecting the VAC in the subgroup without increased AST are high. In the subgroup with increased AST, the sensitivity of Q5 is 100% but the specificity is as low as 27%. Youden's index in the subgroup with increased AST (0.27) is also much lower than in the subgroup without increased AST (0.87).

Discussion

Sacral sparing is according to ISNCSCI essential for the assessment and classification of SCI. Monitoring change of sacral sensory and/or motor function is required for the detection of changes in AIS scores. However, it is not always easy to have the patients examined by health care professionals accurately and timely. In this study, a sacral sparing self-report questionnaire was evaluated for its validity as a self-administered tool for assessment of sensory and motor sacral sparing after SCI.

The feasibility of using self-report to determine S4-5 sensory and motor function has been demonstrated by Harvey, et al.12 In their study, patients were asked to answer four questions regarding the examination of S4-5 LT/PP, DAP and VAC. Reasonable diagnostic accuracy was found among 34 participants with chronic SCI in an outpatient clinic.

In the present study, we further explored the application of self-assessment of sacral sparing within the first year after SCI. Considering that patients may not be familiar with sacral examination, questions described in professional terms would be confusing to them. The self-report questionnaire was specially developed based on experiences during regular bowel management and was made in patient-friendly terms. The questionnaire and the ISNCSCI examination were conducted on the same day for each participant to increase the validity. In addition, influence of increased AST on the accuracy of motor sparing assessment was investigated.

All five questions within this questionnaire are related to the events that most SCI patients experience during their regular bowel routine, such like application of enema and/or digital evacuation, etc. It is easy for them to complete the questionnaire by simply recalling the actual situation. Meanwhile, it is more feasible for repeated assessment, especially in cases where it is not possible to perform anorectal examination. Items were designed to test the S4-5 sensation, DAP and VAC, respectively. Given that patients may have different patterns and habits of defecation, two independent items were provided for the S4-5 sensation and DAP.

Similar to the findings reported by Harvey et al.,12 the accuracy of the questions regarding S4-5 sensation (Q1 and Q2) was good in this study. It is supposed that every person would use either tissue or water for cleaning after defecation. As expected, all participants reported use of tissue and all except one reported use of water, indicating the necessity of including both Q1 and Q2 in the questionnaire. Both Q1 and Q2 show significant agreement with S4-5 sensation examination. This close relationship may be attributed to the common pathway conducting the stimulation of LT/PP during physical examination and of the tissue when cleaning the perianal region after defecation. For Q2, the consistency with S4-5 sensation was not as good as Q1 but still substantial. The reason for this discrepancy may be explained by the different sensory pathways involved. LT/PP, as a kind of superficial sensation, is conducted through the anterior spinothalamic tract, while the sensation of water temperature is conducted through the lateral spinothalamic tract. Injuries to these spinal tracts may be not the same in different individuals with SCI, resulting in a relatively less consistency of Q2 and S4-5 sensation. The sensation of temperature is not included in the ISNCSCI examination, but washing with water was commonly performed during bowel routine. Considering its substantial consistency with S4-5 sensation, it seems relevant to have Q2 included in the questionnaire. For example, Q2 may be much more applicable in some cultural circumstance where washing with water is the dominant manner of cleaning after defecation.

No specific question was designed for the S4-5 LT or PP. This was because neither of them could be mimicked by situations during regular bowel routine. As this questionnaire was only developed to reveal the S4-5 sensation roughly, to indicate possible changes in the patients' perception precise determination of LT/PP was not of primary importance. A substantial consistency of the questionnaire with the general sensation at S4-5 dermatome is acceptable. Once any changes in sensation are reported by the patients during bowel routine, the sacral LT and PP sensation should be evaluated by health care professionals to determine whether further investigations are needed.

Q3 and Q4 are related to the examination of DAP. Most participants used digital evacuation but not all of them while enema was required for everyone, indicating that digital evacuation was not a necessary step during defecation. However, it is still suggested that both these questions be asked. The agreement of Q3 and Q4 with the DAP examination was similar and almost perfect. This result is reasonable because digital evacuation, as well as insertion of an enema, are the same type of stimulation as a DAP examination.

Q5 is a question designed for identification of VAC. The consistency of VAC and Q5 was substantial. For the subgroup with increased AST, agreement was unsatisfactory and not significant. On the other hand, agreement in the subgroup without increased AST was almost perfect. This result reveals a strong influence of increased AST on the interpretation of response for Q5. In patients without increased AST, it is rather reliable as an indicator of preserved VAC. In patients with increased AST, however, care should be taken when a ‘Yes’ is reported because it may be a false-positive result.

Thus, the value of Q5 for individuals with SCI with increased AST is limited. Only for those without increased AST, Q5 could be considered as sensitive and specific enough to reflect the motor sacral sparing. This was similar to the findings by Harvey et al.,12 where a relatively high false-positive rate was found due to the inability of the participants to distinguish between involuntary and voluntary contraction. The fraction of participants with increased AST was not very high (7/51 in the acute phase and 17/51 in the post-acute phase), and therefore this self-report questionnaire can still be beneficial to at least two-third of the participants within the first year post injury.

The validity of this questionnaire in participants with acute and post-acute SCI was similar, except that the consistency of Q2 to S4-5 sensation decreased slightly from almost perfect (κ=0.87) in the acute phase to substantial (κ=0.72) in the post-acute phase. As mentioned above, Q2 was not as accurate as Q1 in reflecting the S4-5 sensation. Whether its accuracy would further decline with time requires further research among individuals with chronic SCI. In the present study, it is reasonable to conclude that Q2 is helpful to the assessment of S4-5 sensation up to 12 months after injury, especially when Q1 is not applicable.

In summary, the 5-item bowel-routine-based SCI sacral sparing self-report questionnaire may be an alternative assessment tool for the population with SCI not feasible to examine in the clinical setting. With the rapid progress of tele-medicine applied in the field of SCI,15 the potential of integrating this self-report tool with personal terminals such as mobile apps will allow for much easier and more efficient evaluation, especially for the patients living at distance from the SCI center. However, this questionnaire is not to replace the anorectal physical examination. Once any change is experienced, patients are suggested to consult the clinician for a standardized physical examination to rule out causes for the changes experienced.

This study has several limitations. First, all participants were inpatients in a single rehabilitation setting; hence, multicenter research is warranted in community settings/outpatient population or in other nationalities/ethnical groups to generalize the result. Second, due to the relatively short time duration from admission to discharge, every participant was assessed for only one time. For this reason, we could not evaluate the responsiveness of this questionnaire to the possible changes in sacral sparing. Finally, only participants within 12 months following SCI were involved. Thus, studies focusing on the responsiveness and long-term efficiency of this questionnaire in individuals with chronic SCI are warranted.

Conclusion

The 5-item SCI sacral sparing self-report questionnaire is a valid tool for sacral sparing assessment for self-administration in individuals with SCI. The validity of this questionnaire for the assessment of sensory sacral sparing is good. For the motor sacral sparing, increased AST may reduce the accuracy of the questionnaire, but the validity is good for those without increased AST. This self-report questionnaire may be considered as a supplemental tool for sacral sparing assessment, especially in the situation where repeated digital rectal examination is not feasible.

Data archiving

There were no data to deposit.

References

Kirshblum SC, Burns SP, Biering-Sorensen F, Donovan W, Graves DE, Jha A et al. International standards for neurological classification of spinal cord injury (Revised 2011). J Spinal Cord Med 2013; 34: 535–546.

DeVivo M, Biering-Sørensen F, Charlifue S, Noonan V, Post M, Stripling T et al. International Spinal Cord Injury Core Data Set. Spinal Cord 2006; 44: 535–540.

Walden K, Bélanger LM, Biering-Sørensen F, Burns SP, Echeverria E, Kirshblum S et al. Development and validation of a computerized algorithm for International Standards for Neurological Classification of Spinal Cord Injury (ISNCSCI). Spinal Cord 2015; 54: 197–203.

Buehner JJ, Forrest GF, Schmidt-Read M, White S, Tansey K, Basso DM . Relationship between ASIA examination and functional outcomes in the neurorecovery network locomotor training program. Arch Phys Med Rehab 2012; 93: 1530–1540.

Scivoletto G, Tamburella F, Laurenza L, Molinari M . Distribution-based estimates of clinically significant changes in the International Standards for Neurological Classification of Spinal Cord Injury motor and sensory scores. Eur J Phys Rehab Med 2013; 49: 373–384.

Lauschke JL, Leong GWS, Rutkowski SB, Waite PME . Changes in electrical perceptual threshold in the first 6 months following spinal cord injury. J Spinal Cord Med 2013; 34: 473–481.

van Middendorp JJ, Hosman AJF, Pouw MH, Van de Meent H . Is determination between complete and incomplete traumatic spinal cord injury clinically relevant? Validation of the ASIA sacral sparing criteria in a prospective cohort of 432 patients. Spinal Cord 2009; 47: 809–816.

Kirshblum SC, Waring W, Biering-Sorensen F, Burns SP, Johansen M, Schmidt-Read M et al. Reference for the 2011 revision of the international standards for neurological classification of spinal cord injury. J Spinal Cord Med 2013; 34: 547–554.

Kirshblum SC, Botticello AL, Dyson-Hudson TA, Byrne R, Marino RJ, Lammertse DP . Patterns of sacral sparing components on neurologic recovery in newly injured persons with traumatic spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehab 2016; 97: 1647–1655.

Samdani A, Chafetz RS, Vogel LC, Betz RR, Gaughan JP, Mulcahey MJ . The international standards for neurological classification of spinal cord injury: relationship between S4-5 dermatome testing and anorectal testing. Spinal Cord 2010; 49: 352–356.

Marino RJ, Schmidt-Read M, Kirshblum SC, Dyson-Hudson TA, Tansey K, Morse LR et al. Reliability and validity of S3 pressure sensation as an alternative to deep anal pressure in neurologic classification of persons with spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehab 2016; 97: 1642–1646.

Harvey LA, Weber G, Heriseanu R, Bowden JL . The diagnostic accuracy of self-report for determining S4–5 sensory and motor function in people with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 2012; 50: 119–122.

Zariffa J, Kramer JL, Jones LA, Lammertse DP, Curt A et alEuropean Multicenter Study about Spinal Cord Injury Study Group. Sacral sparing in SCI: beyond the S4-S5 and anorectal examination. Spine J 2012; 12: 389–400.

Landis JR, Koch GG . The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 1977; 33: 159–174.

Yozbatiran N, Harness ET, Le V, Luu D, Lopes CV, Cramer SC . A tele-assessment system for monitoring treatment effects in subjects with spinal cord injury. J Telemed Telecare 2010; 16: 152–157.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix 1

Appendix 1

Spinal cord injury sacral sparing self-report questionnaire

Q1. Can you feel the tissue when cleaning your perianal area after defecation?

□ Yes

□ No

□ NA, I don't use tissue

Q2. Can you feel the water temperature when washing your perianal area after defecation?

□ Yes

□ No

□ NA, I don't use water

Q3. Can you feel the finger(s) inserting into your rectum during digital evacuation?

□ Yes

□ No

□ NA, I don't use digital evacuation

Q4. Can you feel the enema tube inserted into your rectum during bowel routine?

□ Yes

□ No

□ NA, I don't use enema

Q5. Can you hold the enema for more than 1 minute when it is injected into your rectum?

□ Yes

□ No

□ NA, I don't use enema

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, N., Xing, H., Zhou, MW. et al. Development and validation of a bowel-routine-based self-report questionnaire for sacral sparing after spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 55, 1010–1015 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2017.77

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2017.77

This article is cited by

-

An interview based approach to the anorectal portion of the International Standards of Neurological Classification of Spinal Cord Injury Exam (I-A-ISNCSCI): a pilot study

Spinal Cord (2020)

-

Exploring the relationship between self-reported urinary tract infections to quality of life and associated conditions: insights from the spinal cord injury Community Survey

Spinal Cord (2019)