Abstract

Study design:

Mixed retrospective-prospective cohort study.

Objectives:

To determine 2-year survival following discharge from hospital after spinal cord injury in Bangladesh.

Setting:

Bangladesh.

Methods:

Medical records were used to identify all patients admitted in 2011 with a recent spinal cord injury to the Centre for Rehabilitation of the Paralysed, a large Bangladeshi hospital that specialises in care of people with spinal cord injury. Patients or their families were subsequently visited or contacted by telephone in 2014. Vital status and, where relevant, date and cause of death were determined by verbal autopsy.

Results:

350 of 371 people admitted with a recent spinal cord injury in 2011 were discharged alive from hospital. All but eleven were accounted for two years after discharge (97% follow-up). Two-year survival was 87% (95% CI 83% to 90%). Two-year survival of those who were wheelchair-dependent was 81% (95% CI 76% to 86%). The most common cause of death was sepsis due to pressure ulcers.

Conclusion:

In Bangladesh, approximately one in five people with spinal cord injury who are wheelchair-dependent die within two years of discharge from hospital. Most deaths are due to sepsis from potentially preventable pressure ulcers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Many studies have investigated survival after spinal cord injury in high-income countries.1, 2, 3, 4 However, little is known about survival after spinal cord injury in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), especially after discharge from hospital. Most data on survival after spinal cord injury in LMICs are obtained retrospectively from hospital records and focus on acute survival during the period of hospitalisation immediately after spinal cord injury.1, 5, 6, 7, 8 The few studies that have looked at survival after discharge in LMICs (Zimbabwe, Nepal, Sierra Leone and Bangladesh) report survival ranging from 30 to 75% between 1 and 5 years after discharge.9, 10, 11, 12, 13 These studies are either very small or have high losses to follow-up so they do not provide precise and rigorous estimates of survival.

The largest study of survival in people with spinal cord injury after discharge from hospital in a LMIC was a retrospective chart audit conducted in India. That study reported survival of 86% 5 years after discharge in a sample of 537 patients discharged from a tertiary rehabilitation facility between 1981 and 2011.12 The authors reported an impressive 91% follow-up rate. However, the sample only included those in whom the hospital kept medical records on following discharge. This inclusion criterion is problematic because it is not known how many potential participants were excluded by the failure of the hospital to keep medical records following discharge or whether those people who were excluded had a similar survival rate to the study sample. Few patients were included from the 1980s and 1990s, suggesting that the medical records did not document all patients discharged from the hospital.

Given the limitations of existing data on survival after spinal cord injury in LMICs, we conducted a cohort study to determine survival after spinal cord injury in Bangladesh. Particular care was taken to clearly define the study cohort and to achieve as complete a follow-up as is possible in a LMIC. We followed up patients 2 years after they had been discharged, reasoning that this period was long enough to provide an indication of survival rates but not so long as to make large losses to follow-up unavoidable.

Materials and Methods

Design

Patients admitted to the Centre for Rehabilitation of the Paralysed (CRP) in 2011 were identified retrospectively from hospital records in 2014. The outcome of interest was vital status, which was determined by contacting patients or their families between March and December 2014. Consequently, the study was a mixed retrospective-prospective cohort study. The study received ethical approval from the CRP (CRP/RE/0401/98) and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki Principles. Informed consent was provided by participants or, if the participant had died, from immediate family members.

Setting and participants

Setting

The CRP admits approximately 390 patients a year with recent spinal cord injury.14, 15 This makes the CRP one of the largest acute spinal cord injury units in the world. It receives referrals from all over Bangladesh including referrals from other hospitals. Most patients make a small financial contribution to their care on the basis of the ability to pay, but care is primarily funded by government and not-for-profit organisations.

Participants

The study was conducted on all patients admitted to the CRP in 2011 with a recent spinal cord injury. Most patients were admitted within a few days of their spinal cord injury, but some were admitted to other hospitals and later transferred to the CRP. Patients admitted to the CRP more than 1 year after spinal cord injury were excluded from the study. Eligible patients (study participants) were identified from hospital records. The hospital routinely maintains three sets of records: a list of patients kept by the hospital’s admission centre, a similar list kept by the social welfare department and a detailed medical record kept by the medical record department. All three sets of records were cross-checked to ensure all potential participants were identified. The same records were also used to identify cause of injury (traumatic or non-traumatic), date of injury, the American Spinal Injuries Association Impairment Scale (AIS grade A–E),16 level of injury (tetraplegia or paraplegia) and equipment provided on discharge.

Two cohorts were studied. The first cohort consisted of all study participants. The inception time for this cohort was the date of admission to hospital. Data from the first cohort were used to determine survival in the 2 years following admission to hospital. The second cohort was a subset of the first cohort. It consisted of participants discharged alive from the CRP. The inception time for this cohort was the date of discharge from hospital. Data from the second cohort were used to determine survival in the 2 years after discharge from hospital. The second cohort was the cohort of primary interest but for clarity the cohorts are presented chronologically.

Sample size

The sample size was dictated by available resources. A decision was made to sample 1 year of admissions. This decision was made with the knowledge that ~390 eligible patients are admitted to the CRP each year14, 15 and with the expectation that a 2-year survival would be between 65% and 85%.9, 10, 11, 12, 13 With a sample size of 390 and a survival of 75%, the estimated precision of an estimate of survival is better than ±5%.

Outcome

The outcome was survival. Bangladesh does not have a death registry so an attempt was made to contact every participant or one of his or her family members (or in one case a close friend nominated by the participant when initially admitted to hospital) by telephone in 2014 to ascertain vital status. If a participant or family member could not be contacted by telephone, staff went to the participant’s home. This was a major undertaking, requiring travel by CRP staff to remote parts of Bangladesh. If the participant had died, family members were asked the date of death. Cause of death was determined by asking family members about participants’ symptoms prior to death (that is, verbal autopsy17). CRP records were relied upon for five participants known to have died at CRP within a month of admission and whose family members could not be contacted.

Survival was stratified by whether participants were wheelchair dependent or able to walk at the time of discharge. Ability to walk was used as a surrogate for the severity of injury because the data could be easily and reliably collected over the telephone or from the medical records. The AIS grades were available from the medical records but were not used because they could not be verified. Ability to walk at the time of discharge was determined by asking those participants who were alive in 2014 the following question (in Bangla): ‘On discharge, did you require a wheelchair for mobility on a daily basis?’ Ability to walk at the time of discharge in those who died before being followed up in 2014 was determined from the medical records. Participants were classified as unable to walk on discharge if the medical records specified that they were discharged home with a wheelchair. If the medical records indicated the participant was discharged home with a walking aid (for example, crutches or a frame) then the participant was classified as able to walk. Twenty-six participants were discharged home without any equipment (usually because the participant discharged himself against hospital advice or the participant was referred to another hospital). In these 26 participants, assessment of the ability to walk was based on a combination of the level of injury (tetraplegia versus paraplegia) and the AIS grade. Twenty-two of the 26 participants had AIS A (n=16) or AIS B (n=6) lesions, and 2 participants had AIS C tetraplegia; all were classified as unable to walk. Two participants had AIS D paraplegia and were classified as able to walk.

Data analysis

Data were analysed using Stata v13.1 (College Station, TX, USA). Two analyses were conducted: one on the cohort of participants admitted to the CRP and one on the cohort of participants discharged alive from the CRP. In the first analysis, survival time was time since admission. In the second analysis, survival time was time since discharge. In both analyses, the cumulative probability of survival was determined using the Kaplan–Meier method.18

There were very few missing data. Only 11 participants were lost to follow-up. Therefore, the analysis was conducted using case-wise deletion. A simple sensitivity analysis was conducted in which the worst-case and the best-case scenarios were imputed for the 11 participants lost to follow-up.19 The worst-case scenario assumed that all 11 died one day after discharge. The best-case scenario assumed that all 11 were alive on 31 December 2014.

Results

Survival from admission

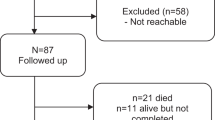

Three hundred and seventy-one people were admitted to CRP in 2011 with a recent spinal cord injury (Figure 1 and Table 1). Of these, 11 participants (3%) were lost to follow-up after discharge and therefore were censored one day after discharge. Included in the 11 lost to follow-up was one participant whose death after discharge was confirmed but whose date of death could not be determined. The remaining 360 participants (97%) of the cohort contributed survival data until they died or were followed up. Median follow-up time was 34.4 months (interquartile range 31.0–37.8 months) and total person-time of follow-up was 11 157 months. Seventy-five participants had died at follow-up, of whom 20 died in the first month after admission. The 2-year survival from the time of admission was 83% (95% confidence interval (CI), 79–87%), and the annual mortality rate from the time of admission was 0.08 deaths per person-year (95% CI, 0.07–0.10; Figure 2). Sensitivity analyses that imputed worst-case and best-case outcomes for the 11 missing participants lost to follow-up yielded nearly identical estimates of 2-year survival (worst-case 83%, best-case 84%).

Survival from discharge

Three hundred and fifty participants admitted to CRP in 2011 with a recent spinal cord injury survived until discharge. Of these, 339 participants (97%) contributed survival data until they died or were followed up. Median follow-up time for this cohort was 31.4 months (interquartile range 27.6–34.8 months) and total person-time of follow-up was 9937 months. Fifty-four participants had died at follow-up (excluding one participant who died, but date of death was not known), giving a 2-year survival rate from the time of discharge of 87% (95% CI, 83–90%) and an annual mortality rate from the time of discharge of 0.07 deaths per person-year (95% CI, 0.05–0.09; Figure 3). The hazard was slightly higher in the first few months after discharge but was nearly constant thereafter. Again, sensitivity analyses that imputed worst-case and best-case outcomes for the 11 participants lost to follow-up yielded nearly identical estimates of 2-year survival (worst case, 87%; best case, 88%).

Two hundred and twenty-eight of the 350 participants discharged home were wheelchair dependent on discharge. All but four of the 54 deaths (93% of deaths) occurred in those who were wheelchair dependent. The 2-year survival for those who were wheelchair dependent was 81% (95% CI, 76–86%), whereas the 2-year survival for those who were walking was 98% (95% CI, 94–100%; Figure 4).

Cause of death

Causes of death are shown in Table 1. The most common cause of death prior to discharge was respiratory failure (n=13/21, 62%). The most common cause of death after discharge was sepsis due to pressure ulcers (n=30/54, 56%).

Discussion

This study provides the first robust estimates of survival following discharge from hospital with spinal cord injury in a LMIC. The strengths of this study were the clear definition of the study cohorts and the high rate of follow-up. All admissions in 2011 were identified, and vital status in 2014 was ascertained in 97% of participants. A sensitivity analysis demonstrated that the estimates of survival were insensitive to the small number of missing outcomes. Ambiguities about the study cohort and loss to follow-up have been the biggest limitations of past studies conducted in LMICs.1

There were a number of limitations to our study. One is that families of participants were sometimes unable to nominate the exact date of death. When that occurred, they were asked to estimate the date. Such estimates are prone to error, but it is difficult to correct estimates of survival for such errors when the pattern of the errors is not known. Another limitation of the study was that data on wheelchair use were self-reported by those participants who were alive at follow-up and were extracted from the medical records in those participants who died before follow-up. A small number of participants may have been misclassified. A further limitation is that 27 participants were discharged from CRP to another hospital for acute medical problems. Of these 14 died, 11 were still alive in 2014 and 2 (one of whom died) were lost to follow-up. The 14 participants who died were considered to have died after discharge even though 11 died within 3 days of discharge from CRP to another hospital. The other 3 died between 3 and 28 months after discharge from CRP.

To some extent the estimates of survival after discharge provided by this study can be generalised to other hospitals in Bangladesh and other LMICs. Most people with spinal cord injury in Bangladesh and some other LMICs are discharged from hospital into environments similar to those in which the patients from CRP were discharged, where there is little or no access to disability or health services. Survival in such environments will depend on the severity of injury and might depend on the pre-discharge quality of hospital care. It is not known how the severity of injury of patients discharged from CRP compares with the severity of injury of patients discharged from other hospitals in Bangladesh and other LMICs. Moreover, although the quality of hospital care provided by a specialist spinal cord injury centre like CRP is likely to be better than that in other hospitals, it is not known if or how much the quality of hospital care influences survival after discharge. Until these questions are resolved, the current data provide the best estimates of survival after discharge from hospital with a spinal cord injury in Bangladesh and other LMICs.

Most of the participants who died prior to discharge died of respiratory failure. In contrast, most of the participants who died after discharge died from sepsis due to pressure ulcers. The latter finding is consistent with reports of a very high prevalence of pressure ulcers in people with spinal cord injury living in LMICs.13, 20 It is thought that pressure ulcers can be prevented with simple, inexpensive interventions such as regular change in position and the use of cushions on wheelchairs and foam overlays on beds.21 These considerations suggest that interventions to improve survival after discharge from hospital with spinal cord injury in LMICs should focus on prevention of pressure ulcers. However, it is difficult to know how best to intervene. Currently, patients from CRP who are wheelchair dependent are discharged home with foam cushions typically funded by the hospital. They are also educated about skin care. Possibly, patients require ongoing education and support after discharge. This has prompted us to commence a clinical trial examining a low-cost model of community-based support specifically aimed at preventing pressure ulcers and other complications (for details see www.anzctr.org.au/Trial/Registration/TrialReview.aspx?id=364277).

Over 90% of participants in the cohort were men. This could indicate either that, in Bangladesh, men are much more likely compared with women to experience a spinal cord injury, or that men are much more likely compared with women to be referred to CRP or both. A population-based cohort study conducted on all people who experience spinal cord injury in a geographical area would be required to explore these possibilities, but such a study would be difficult to conduct. Most participants sustained their spinal cord injury due to trauma; however, 20 participants had non-traumatic spinal cord injuries. Six of these people had died by the 2-year follow-up. It was not possible to do secondary survival analyses for those with non-traumatic spinal cord injury or any other variable because the subgroups were too small and the estimates of survival would have been imprecise.

The main finding from this study is that, in Bangladesh, approximately one in five people with spinal cord injury who are wheelchair dependent die within 2 years of discharge from hospital. Most of these deaths are due to sepsis from potentially preventable pressure ulcers.

Data Archiving

There were no data to deposit.

References

World Health Organization International Perspectives on Spinal Cord Injury 2013. Geneva, Switzerland.

Frankel HL, Coll JR, Charlifue SW, Whiteneck GG, Gardner BP, Jamous MA et al. Long-term survival in spinal cord injury: a fifty year investigation. Spinal Cord 1998; 36: 266–274.

Strauss DJ, Devivo MJ, Paculdo DR, Shavelle RM . Trends in life expectancy after spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2006; 87: 1079–1085.

Middleton JW, Dayton A, Walsh J, Rutkowski SB, Leong G, Duong S . Life expectancy after spinal cord injury: a 50-year study. Spinal Cord 2012; 50: 803–811.

World Health Organization and The World Bank World Report on Disability 2011. World Health Organization Press, Geneva, Switzerland.

Nwadinigwe CU, Iloabuchi TC, Nwabude IA . Traumatic spinal cord injuries (SCI): a study of 104 cases. Niger J Med 2004; 13: 161–165.

Kawu AA, Alimi FM, Gbadegesin AA, Salami AO, Olawepo A, Adebule TG et al. Complications and causes of death in spinal cord injury patients in Nigeria. West Afr J Med 2011; 30: 301–304.

Correa GI, Finkelstein JM, Burnier LA, Danilla SE, Tapia LZ, Torres VN et al. Work-related traumatic spinal cord lesions in Chile, a 20-year epidemiological analysis. Spinal Cord 2011; 49: 196–199.

Scovil CY, Ranabhat MK, Craighead IB, Wee J . Follow-up study of spinal cord injured patients after discharge from inpatient rehabilitation in Nepal in 2007. Spinal Cord 2012; 50: 232–237.

Gosselin RA, Coppotelli C . A follow-up study of patients with spinal cord injury in Sierra Leone. Int Orthop 2005; 29: 330–332.

Razzak A, Helal SU, Nuri RP . Life expectancy after spinal cord injury in a developing country - a retrospective study at CRP, Bangladesh. DCIDJ 2011; 22: 114–123.

Barman A, Shanmugasundaram D, Bhide R, Viswanathan A, Magimairaj HP, Nagarajan G et al. Survival in persons with traumatic spinal cord injury receiving structured follow-up in South India. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2014; 95: 642–648.

Levy LF, Makarawo S, Madzivire D, Bhebhe E, Verbeek N, Parry O . Problems, struggles and some success with spinal cord injury in Zimbabwe. Spinal Cord 1998; 36: 213–218.

Centre for Rehabilitation of the Paralyzed. Annual Report: July 2009 to June 2012 CRP Printing Press: Bangladesh. 2010.

Centre for Rehabilitation of the Paralyzed. Annual Report: 2012-2013, Ability not disability CRP Printing Press: Bangladesh. 2010.

Kirshblum SC, Burns SP, Biering-Sorensen F, Donovan W, Graves DE, Jha A et al. International standards for neurological classification of spinal cord injury (revised 2011). J Spinal Cord Med 2011; 34: 535–546.

Murray CJ, Lopez AD, Black R, Ahuja R, Ali SM, Baqui A et al. Population Health Metrics Research Consortium gold standard verbal autopsy validation study: design, implementation, and development of analysis datasets. Popul Health Metr 2011; 9: 27.

Clark TG, Bradburn MJ, Love SB, Altman DG . Survival analysis part I: basic concepts and first analyses. Br J Cancer 2003; 89: 232–238.

Clark TG, Bradburn MJ, Love SB, Altman DG . Survival analysis part IV: further concepts and methods in survival analysis. Br J Cancer 2003; 89: 781–786.

Zakrasek EC, Creasey G, Crew JD . Pressure ulcers in people with spinal cord injury in developing nations. Spinal Cord 2015; 53: 7–13.

European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel and National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel Prevention and Treatment of Pressure Ulcers: Quick Reference Guide. Washington, DC, National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel. 2009.

Acknowledgements

We thank all staff and patients from the Centre for the Rehabilitation of the Paralysed who helped collect data. We also thank the staff from the admissions/discharge and social welfare departments for their diligent record keeping in 2011. This work was supported by two Bridging Support Grants from The University of Sydney, Australia [171654 and 2013-00033].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

MSH, MAR and MMQ are employed by the Centre for the Rehabilitation of the Paralysed and received salary support to conduct the submitted work. Readers may perceive that they have an interest in portraying good survival following admission and discharge from this centre. The remaining authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hossain, M., Rahman, M., Herbert, R. et al. Two-year survival following discharge from hospital after spinal cord injury in Bangladesh. Spinal Cord 54, 132–136 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2015.92

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2015.92

This article is cited by

-

An assessment of disability and quality of life in people with spinal cord injury upon discharge from a Bangladesh rehabilitation unit

Spinal Cord (2023)

-

In-hospital mortality in people with complete acute traumatic spinal cord injury at a tertiary care center in India—a retrospective analysis

Spinal Cord (2022)

-

Telerehabilitation for individuals with spinal cord injury in low-and middle-income countries: a systematic review of the literature

Spinal Cord (2022)

-

Incidence, severity and time course of pressure injuries over the first two years following discharge from hospital in people with spinal cord injuries in Bangladesh

Spinal Cord (2022)

-

Successful outcomes of endoscopic lithotripsy in completely bedridden patients with symptomatic urinary calculi

Scientific Reports (2020)