Abstract

Study design:

Literature review/semi-structured interviews.

Objective:

To develop a spinal cord injury (SCI) research strategy for Australia and New Zealand.

Setting:

Australia.

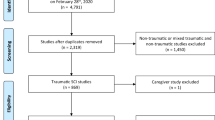

Methods:

The National Trauma Research Institute Forum approach of structured evidence review and stakeholder consultation was employed. This involved gathering from published literature and stakeholder consultation the information necessary to properly consider the challenge, and synthesising this into a briefing document.

Results:

A research strategy ‘roadmap’ was developed to define the major steps and key planning questions to consider; next, evidence from published SCI research strategy initiatives was synthesised with information from four one-on-one semi-structured interviews with key SCI research stakeholders to create a research strategy framework, articulating six key themes and associated activities for consideration. These resources, combined with a review of SCI prioritisation literature, were used to generate a list of draft principles for discussion in a structured stakeholder dialogue meeting.

Conclusion:

The research strategy roadmap and framework informed discussion at a structured stakeholder dialogue meeting of 23 participants representing key SCI research constituencies, results of which are published in a companion paper. These resources could also be of value in other research strategy or planning exercises.

Sponsorship:

This project was funded by the Victorian Transport Accident Commission and the Australian and New Zealand Spinal Cord Injury Network.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Considerable research effort is directed towards finding ways to either repair the damage associated with spinal cord injury (SCI) or manage these secondary consequences of the injury. High-quality, high-impact research underpins clinical practice and policy that can ultimately improve the lives of people with traumatic and non-traumatic SCI.1, 2, 3 However, conducting such a research is challenging and requires a shared understanding between research stakeholders of SCI research priorities, activities and opportunities. To this end, in recent years, the SCI research community has engaged in a variety of initiatives aimed at optimising SCI research planning, conduct and outputs, for example, through the following:

-

Formation of collaborative networks, such as the Spinal Cord Injury Network,4 North American Clinical Trials Network,5, 6 NeuroRecovery Network7 and European Multicentre Study about Spinal Cord Injury;8

-

Development of a grading system and other strategies to evaluate the readiness of preclinical studies for clinical translation;9, 10

-

Development of guidelines for the conduct of SCI clinical trials, such as the International Campaign for Cures of Spinal Cord Injury Paralysis series11, 12, 13, 14 and for preclinical research, through the United States National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke15 and, more recently, guidelines for reporting through the Minimum Information about a Spinal Cord Injury experiment project;16

-

Development of SCI patient registries, such as the Australian Spinal Cord Injury Register19 and the Rick Hansen Spinal Cord Injury Registry in Canada,20 to facilitate research, injury monitoring and benchmarking.

To build upon such initiatives, this project aimed to develop a unified, regional (Australian and New Zealand) SCI research strategy that

-

Addresses SCI research priorities;

-

Harnesses research collaborations to optimise research quality and impact and minimise duplication of research effort;

-

Minimises the burden on patients with SCI who participate in the research; and

-

Can assist research funders by articulating principles underpinning high-quality, high-impact research in this field.

Methods

To address this aim, the National Trauma Research Institute (NTRI) collaborated with the Spinal Cord Injury Network as part of the NTRI Forum program,21 a 3-year research program established in 2012 and funded by the Victorian Transport Accident Commission. The NTRI Forum aims to improve the care of people with brain, spinal cord or other major traumatic injuries through two phases of activity:

Phase 1:

-

Defining a major challenge in the brain or SCI through consultation with key stakeholders to understand the issues and complexities; and

-

Gathering from published literature and further consultation the information necessary to properly consider the challenge and presenting this in a briefing document.

Phase 2:

-

Convening stakeholder dialogues to connect the information from the briefing document with the people who can make change happen (clinicians, researchers, people with SCI, advocacy organisations, health system managers, policy-makers and funding agencies); and

-

Briefing the organisations and individuals who can effect change about their role in developed strategies.21

The NTRI Forum is modelled on the Canadian McMaster Health Forum, established in 2009 by John Lavis, to support evidence-informed health systems and address a broad range of health policy challenges in Canada.22, 23 Evaluation of the McMaster model of evidence briefs and structured stakeholder consultations has demonstrated that this approach appears to be highly regarded by participants and leads to intentions to act.24

This paper describes the outcomes of Phase 1 of the NTRI Forum process––that is, defining the problem, then synthesising and summarising evidence from literature and consultations into a briefing document. Companion papers present a review of prioritisation literature that informed Phase 125 and the outcomes of Phase 2.26 We certify that all applicable institutional and governmental regulations concerning the ethical use of human volunteers were followed during the course of this research.

Results

In addition to the rapid review of evidence,25 there were four key outputs from Phase 1 of the Research Strategy Forum:

-

1

A Research Strategy Roadmap that presents an overview of the major steps and outlines key planning questions––that is, the HOW of a research strategy;

-

2

A Research Strategy Framework articulating six research strategy domains and examples of specific strategies and activities addressing these domains––that is, the WHAT of a research strategy;

-

3

A Draft Set of Principles drawn from the research strategy framework to act as a starting point for discussion and deliberation at the stakeholder dialogue; and

-

4

A set of three Draft Options for Consideration within and following the stakeholder dialogue.

1. Research strategy roadmap: The ‘HOW’ of a research strategy

At the outset of this NTRI Forum, it was clear that development of a research strategy was a complex, multifaceted task. Health research stakeholders may have differing and potentially conflicting perspectives on what a research strategy means, looks like or should achieve. Perspectives of patients and carers regarding research priorities based on their lived experience of SCI may be quite different from that which clinicians deem important.27 For example, a researcher may have a narrower focus and consider specific infrastructure, human resources or other research support needs; research funders and service delivery organisations may be driven by return on investment or the overall impact of a research project on a health or a compensation system.

To this end, a ‘research strategy roadmap’ (Figure 1) outlining key steps in the process was developed to provide a guide to the ‘how’ of developing a research strategy. The roadmap was based on a checklist of themes representing good practices in health research priority setting, developed by the World Health Organization,28 and a qualitative study of key health-care stakeholders that resulted in the development of a conceptual health priority-setting framework.29

The roadmap identified questions pertaining to each step in the process for deliberation by key stakeholders in SCI research. It was decided to focus the NTRI Forum on Stage 1 of the roadmap because of the following:

-

Consideration and determination of the aims of the strategy, resources available and other factors that could influence the strategy and are critical to subsequent planning and development;

-

The principles considered important to high-quality SCI research may vary between various stakeholder groups. Beginning the process of understanding, discussing and resolving these differences to create a unified set of principles is an important initial task28; and

-

The participants in the Forum process did not have a specified mandate or authority to progress development of a regional SCI research strategy; wider consultation with identified stakeholders following the Forum was required to seek input on the draft set of principles and the next steps in strategy development and determine who will lead the next steps in the process.

2. Research strategy framework: The ‘WHAT’ of a research strategy

To inform deliberations at the stakeholder dialogue, views and information on the development of a SCI research strategy were gathered through one-on-one key informant consultation and a review of previous SCI research strategy initiatives. The key informant consultation involved qualitative, semi-structured one-on-one interviews of approximately 30 min with four individuals with extensive experience in SCI research, research administration and clinical practice. Unlike quantitative research, in which a random sample is chosen to facilitate generalisation to a larger population, qualitative research involves purposefully sampling a small number of participants based on their specific knowledge or experience of the phenomenon of interest.30, 31, 32, 33 In this project, an in-depth understanding of SCI research issues and how they may be addressed was facilitated by generating initial themes from the four semi-structured interviews as described below. These themes were further developed in the Phase 2 stakeholder dialogue, which brought together 23 key stakeholders in SCI research.26

The four chosen participants, identified through the expert panel overseeing this NTRI Forum and contacted directly via email, had expert knowledge of SCI research as follows:

-

Participant 1 had a 24-year experience in SCI research comprising 4 years as a basic scientist and 20 years in research administration, including 11 years as a research Program Director for the US National Institutes of Health (NIH).

-

Participant 2 had 7 years of SCI research experience in the areas of community participation and in reviewing bowel, bladder and sexual health literature and 5-year SCI clinical experience as a physical therapist.

-

Participant 3 experienced an SCI at C4-C5 level in 1971, initiated Australia’s first SCI registry and has consulted as an actuary in a number of SCI forums and initiatives.

-

Participant 4 had a background in SCI project management and 4-year postdoctoral research experience focussing on SCI research priorities from both consumer and researcher perspectives.

The interviews focused on four questions:

-

1

Briefly describe your experience in the field of SCI research.

-

2

From your perspective, what are the big challenges in SCI research today?

-

3

How do you think a research strategy could best address these challenges?

-

4

What principles could guide the strategic planning of SCI research in order to optimise research quality and impact?

Notes were taken during these consultations, but no audio was recorded. A line-by-line content analysis of these notes was used to generate themes representing the information gathered.

Initial themes identified from stakeholder consultation interviews were as follows:

-

Standards of care: Although there are large repositories of SCI research knowledge, currently there are more treatment ‘options’ than definitive standards. In some cases, clinical use has preceded the development of an evidence base. These factors have led in some instances to an unscientific, ‘wild west’ approach with practitioners using or promoting treatments that are not supported by high-level evidence and/or expert consensus.

-

Optimising research: A number of challenges to optimising SCI research were identified, ranging from difficulties in recruiting adequate numbers of participants with SCI leading to underpowered clinical trials to the need to standardise laboratory or animal models in basic research. These challenges can be addressed by enhancing communication between researchers––for example, through meetings, enhanced discussion and publication of research protocols and findings and the use of virtual/social networks. Such strategies could also foster more interdisciplinary dialogue—for example, to incorporate bioengineering perspectives. However, it was acknowledged that strategies directed at fostering large collaborative studies involve striking a delicate balance between promoting creativity (the need to pursue innovative lines of enquiry) and regulation (the need to consolidate research efforts to maximise explanatory power). Other identified strategies for optimising research quality included setting targets for establishing therapy viability within lines of research enquiry and abandoning research if these are not met; strengthening peer review processes; mandating that research conforms to particular standards if a research grant is substantial; conducting replication studies to verify or refute findings from preclinical studies; and data harmonisation and sharing.

-

Translation and implementation: Challenges identified were lack of translation of laboratory work into new drugs and therapies and pressure to implement high-profile, expensive therapies that are not accessible to many patients with SCI. The need was identified for SCI research to impact upon as many SCI stakeholders as possible (for example, rather than impact being limited to those with SCI who can afford therapies or high-resource countries).

-

Consumer engagement and input: The need to ensure that research is relevant and significant to consumers was identified, as well as the need for greater engagement between consumers and researchers to connect identified priorities to the research effort. Examples of such work include studies examining the priorities of people with SCI27 and their views on specific therapies, such as tendon transfer surgery.34

-

Moving research ‘beyond the hospital’: The need to foster research beyond a focus on cure, best treatment and medical complications was identified. It was felt that greater attention should be given to the following:

-

Developing models of service delivery for SCI rehabilitation;

-

Determining the optimal timing, intensity and focus of therapy;

-

Addressing psychosocial aspects, such as the role of resilience, family sustainability, depression and motivation in coping with day-to-day living;

-

Overcoming impediments to community participation; and

-

Maintaining health, well-being and quality of life in the long term.

-

In addition to the specific themes identified above, participants in the consultation interviews felt that an SCI research strategy should do the following:

-

Articulate its fundamental aim;

-

Encompass all phases of SCI research––that is, from basic science to human clinical trials;

-

Consolidate information about ‘hot topics’ and current research to get a bigger picture of the research landscape and determine gaps, as current research planning is opportunistic and driven by academics and clinicians rather than the needs of the target population. However, moving to a model that is less researcher driven could reduce motivation for researchers;

-

Inform a national reporting and monitoring framework, for example, through links to a registry or database;

-

Harness the potential of registries that continuously capture data, which can form a basic data set that can be supplemented by other items. This may address the limits to applicability of the randomised controlled trial model, which is based around carefully controlled experiments; and

-

Consider the importance of implementation research, as many breakthroughs fall down at the point of implementation.

In addition to a rapid review of evidence focusing on SCI research priorities,25 six previous SCI research strategy initiatives across 10 publications were identified through the consultation interviews. All except one35 originated from outside of Australia. Information on organisations involved, stakeholder participation and aims/scope of the various initiatives and key themes/recommendations is presented in Table 1.

The six identified SCI research strategy initiatives illustrate the breadth of SCI research strategy challenges. Collectively, they encompass basic, clinical and translational research and have diverse aims—determining the research needs of the SCI community;35 prioritising research funding;42, 43, 44 reviewing the state of the science;36 in-depth exploration of specific research topics37; and promotion and translation of completed research.38 Similar diversity can be found in the resulting recommendations, which include enhanced research training,36 improving research infrastructure35, 36 and trial co-ordination,36, 37, 42 in addition to identification of specific research topic areas.35, 38, 39, 41, 42

Given the diversity of concepts elucidated by the one-on-one interviews and the identified research strategy publications, information from both of these sources was synthesised into a unifying Research Strategy Framework articulating six themes, underpinned by examples of strategies and activities (Table 2).

3. Draft set of principles

A draft set of principles of a research strategy were developed in order to inform the Phase 2 stakeholder dialogue.26 The draft principles, drawn from the data gathered from the initial stakeholder consultations and literature reported above, encompassed the six themes identified by the research strategy framework. For each draft principle, a set of questions for deliberation was outlined to prompt discussion at the stakeholder dialogue. Three questions were posed for all draft principles:

-

1

Should this principle be adopted?

-

a

As currently worded?

-

b

With modifications? If so,

-

a

-

2

What is the rationale for this principle?

-

3

What resources and information can inform operationalisation of this principle?

Further questions specific to each individual principle were also developed. Examples of these questions are contained in Table 3. The prompting questions were a combination of generic questions dealing with broad research concepts (for example ‘How is ‘priority’ defined––that is, what are the appropriate prioritisation criteria?’) and questions designed to elucidate more specific to the Australian and New Zealand SCI research environment (for example ‘What local and international methods of co-ordinating patient involvement in research exist?’). This enabled the dialogue to draw upon both international and local attendees, facilitated comparison and harmonisation of a local research strategy with related international initiatives and elucidated the information that the local SCI research environment required to enact a regional strategy that responded to specific contextual needs.

4. Draft options for consideration

Although the range of potential SCI research strategy activities to follow-up after the Forum was dependent upon deliberations at the stakeholder dialogue, a set of three options for moving the research strategy forward was developed for consideration:

-

OPTION 1: Prepare a paper/position statement reflecting the agreed principles of high-quality SCI research and disseminate this to SCI research stakeholders (for example, through a journal publication, conference presentation, website and other channels).

-

OPTION 2: Option 1 plus further development of a regional (Australia and New Zealand) SCI research strategy that is voluntary (that is, people can choose to follow or not follow the recommendations within the strategy).

-

OPTION 3: Option 1 plus further development of a regional (Australia and New Zealand) SCI research strategy based on the roadmap that is constituted by a national body (involving formal processes of approval of research).

The SCI research strategy roadmap, framework, draft set of principles and options for consideration to further advance the strategy were assembled into a briefing document. This document was sent to 23 SCI research stakeholders representing basic scientists, clinical researchers, administrators, consumer advocates, policy makers and funders 1 week prior to the Phase 2 structured stakeholder dialogue to guide dialogue deliberations. The results of the stakeholder dialogue are reported in a companion paper.26

Discussion

This was the first known project that aimed to develop a unified, regional (Australian and New Zealand) SCI research strategy. The process of gathering background data and creating meaningful and useful frameworks to facilitate development of the strategy was challenging on a number of levels. First, development of a research strategy is a complex task that requires the sustained commitment of multiple research stakeholder groups, which include researchers, clinicians, funders, persons with SCI and their carers, advocacy organisations and policymakers. To convey an overview of the key tasks in the process, we chose to develop a research strategy ‘roadmap.’ This had the advantage of giving the SCI research community a full view of the breadth and nature of the tasks involved in developing, implementing and assessing the impact of a research strategy. One disadvantage of this approach is that research strategy development is not linear; in reality, considerations of who should lead the strategy, information needs and implementation plans inevitably become part of the initial discussion of the context and aims of the strategy. However, breaking the task of research strategy development into conceptual steps did enable determination of a starting point and focus of the Forum.

Second, a ‘research strategy’ is a multifaceted concept, as evidenced by the breadth of SCI research strategy development efforts identified in research strategy reports and journal publications. Similarly, initial stakeholder consultation revealed a broad range of issues relating to strategic planning and conduct of SCI research. Although we could have focussed on a specific area of research strategy for this Forum, we did not want to presuppose where the SCI community wanted to begin their research strategy development. We chose to propose a list of draft principles encompassing the six themes within the research strategy framework at the stakeholder dialogue. Another approach could have been to leave this open for discussion. However, unstructured discussion carries the risk of being unfocussed, leaving participants dissatisfied. For this reason and based on our experience in the Forum process over a number of topics, we have found that drafting material for discussion is a better approach than having an ‘open forum’, even if draft materials are criticised, heavily modified or abandoned. The draft options for consideration were developed on the same principles.

We did not conduct a traditional database-driven systematic search for research strategy planning publications in this project for two reasons. First, research strategy documents are often in report form rather than peer-reviewed journal publications and therefore are not indexed in medical literature databases. Therefore, they are best identified through direct consultation with experts in the field. Our liaison with such experts through the one-on-one interviews reinforced the value of this approach—four of the six research strategies identified were in report rather than journal form. Second, a systematic search for related literature had already been undertaken as part of our rapid review pertaining to SCI research priorities.25 An advantage of our multi-faceted approach to the identification of literature is that this enabled a better understanding of the breadth and nature of SCI research strategy activity. For example, although our rapid review of evidence pertaining to SCI research priorities25 noted a lack of broad stakeholder engagement in SCI research prioritisation, the report-based strategy documents demonstrate wider engagement of researchers, clinicians, funders and other stakeholders in SCI research planning.

The research strategy roadmap and framework presented herein are of potential use to research strategy development in areas other than SCI. However, some issues specific to SCI research strategy development may not be relevant to other research areas. The relatively small number of participants with SCI available for clinical trials is one example. Area-specific research issues should therefore be borne in mind when considering the use of these resources to develop research strategy in other fields.

Results of dialogue deliberations and a discussion of these findings in the context of the international SCI research environment are presented in a companion paper.26

References

Noonan VK, Soril L, Atkins D, Lewis R, Santos A, Fehlings MG et al. The application of operations research methodologies to the delivery of care model for traumatic spinal cord injury: the access to care and timing project. J Neurotrauma 2012; 29: 2272–2282.

Craven C, Balioussis C, Verrier MC, Hsieh JT, Cherban E, Rasheed A et al. Using scoping review methods to describe current capacity and prescribe change in Canadian SCI rehabilitation service delivery. J Spinal Cord Med 2012; 35: 392–399.

Guihan M, Bosshart HT, Nelson A . Lessons learned in implementing SCI clinical practice guidelines. SCI Nurs 2004; 21: 136–142.

The Spinal Cord Injury Network, 2011http://www.spinalnetwork.org.au/ (accessed 9 April 2013).

Christopher and Dana Reeve Foundation. North American Clinical Trials Network, 2014 http://www.christopherreeve.org/site/c.ddJFKRNoFiG/b.8720879/k.B691/NACTN.htm (accessed 26 August 2014).

Guest J, Harrop JS, Aarabi B, Grossman RG, Fawcett JW, Fehlings MG et al. Optimization of the decision-making process for the selection of therapeutics to undergo clinical testing for spinal cord injury in the North American Clinical Trials Network. J Neurosurg Spine 2012; 17 (Suppl 1): 94–101.

Christopher and Dana Reeve Foundation. NeuroRecovery Network, 2012 http://www.christopherreeve.org/site/c.ddJFKRNoFiG/b.5399929/k.6F37/NeuroRecovery_Network.htm (accessed 18 February 2013).

European Multicentre Study about Spinal Cord Injury, 2013http://www.emsci.org/ (accessed 25 August 2014).

Kwon BK, Okon EB, Tsai E, Beattie MS, Bresnahan JC, Magnuson DK et al. A grading system to evaluate objectively the strength of pre-clinical data of acute neuroprotective therapies for clinical translation in spinal cord injury. J Neurotrauma 2011; 28: 1525–1543.

Kwon BK, Soril LJ, Bacon M, Beattie MS, Blesch A, Bresnahan JC et al. Demonstrating efficacy in preclinical studies of cellular therapies for spinal cord injury—how much is enough? Exp Neurol 2013; 248: 30–44 Erratum in: Exp Neurol. 2013; 248: 299–300.

Fawcett JW, Curt A, Steeves JD, Coleman WP, Tuszynski MH, Lammertse D et al. Guidelines for the conduct of clinical trials for spinal cord injury as developed by the ICCP panel: spontaneous recovery after spinal cord injury and statistical power needed for therapeutic clinical trials. Spinal Cord 2007; 45: 190–205.

Tuszynski MH, Steeves JD, Fawcett JW, Lammertse D, Kalichman M, Rask C et al. Guidelines for the conduct of clinical trials for spinal cord injury as developed by the ICCP Panel: clinical trial inclusion/exclusion criteria and ethics. Spinal Cord 2007; 45: 222–231.

Steeves JD, Lammertse D, Curt A, Fawcett JW, Tuszynski MH, Ditunno JF et al. Guidelines for the conduct of clinical trials for spinal cord injury (SCI) as developed by the ICCP panel: clinical trial outcome measures. Spinal Cord 2007; 45: 206–221.

Lammertse D, Tuszynski MH, Steeves JD, Curt A, Fawcett JW, Rask C et al. Guidelines for the conduct of clinical trials for spinal cord injury as developed by the ICCP panel: clinical trial design. Spinal Cord 2007; 45: 232–242.

Landis SC, Amara SG, Asadullah K, Austin CP, Blumenstein R, Bradley EW et al. A call for transparent reporting to optimize the predictive value of preclinical research. Nature 2012; 490: 187–191.

Lemmon VP, Ferguson AR, Popovich PG, Xu XM, Snow DM, Igarashi M et al. Minimum information about a spinal cord injury experiment: a proposed reporting standard for spinal cord injury experiments. J Neurotrauma 2014; 31: 1354–1361.

Biering-Sorensen F, Charlifue S, Devivo MJ, Grinnon ST, Kleitman N, Lu Y et al. Using the spinal cord injury common data elements. Top Spinal Cord Inj Rehabil 2012; 18: 23–27.

DeVivo MJ, Biering-Sorensen F, New P, Chen Y . Standardization of data analysis and reporting of results from the International Spinal Cord Injury Core Data Set. Spinal cord 2011; 49: 596–599.

Norton L Spinal Cord Injury, Australia 2007–08. Injury Research and Statistics Series no. 52. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare: Canberra, Australia, 2010.

Noonan VK, Kwon BK, Soril L, Fehlings MG, Hurlbert RJ, Townson A et al. The Rick Hansen Spinal Cord Injury Registry (RHSCIR): a national patient-registry. Spinal Cord 2012; 50: 22–27.

NTRI Forum—Improving Care of the Injured, 2014http://www.ntriforum.org.au/ (accessed 31 July 2014).

Lavis JN, Posada FB, Haines A, Osei E . Use of research to inform public policymaking. Lancet 2004; 364: 1615–1621.

Lavis JN . How can we support the use of systematic reviews in policymaking? PLoS Med 2009; 6: e1000141.

Moat KA, Lavis JN, Clancy SJ, El-Jardali F, Pantoja T,, Knowledge Translation Platform Evaluation study team. Evidence briefs and deliberative dialogues: perceptions and intentions to act on what was learnt. Bull World Health Organ 2014; 92: 20–28.

Bragge P, Piccenna L, Middleton JW, Williams S, Creasey G, Dunlop S et al. Developing a spinal cord injury research strategy using a structured process of evidence review and stakeholder dialogue. Part I: Rapid review of SCI prioritisation literature. Spinal Cord, (doi:10.1038/sc.2015.85).

Middleton JW, Piccenna L, Gruen RL, Williams S, Creasey G, Dunlop S et al. Developing a spinal cord injury research strategy using a structured process of evidence review and stakeholder dialogue. Part III: Outcomes. Spinal Cord, (doi:10.1038/sc.2015.87).

Anderson KD . Targeting recovery: priorities of the spinal cord-injured population. J Neurotrauma 2004; 21: 1371–1383.

Viergever RF, Olifson S, Ghaffar A, Terry RF . A checklist for health research priority setting: nine common themes of good practice. Health Res Policy Syst 2010; 8: 36.

Sibbald SL, Singer PA, Upshur R, Martin DK . Priority setting: what constitutes success? A conceptual framework for successful priority setting. BMC Health Services Res 2009; 9: 43.

Coyne IT . Sampling in qualitative research. Purposeful and theoretical sampling; merging or clear boundaries? J Adv Nurs 1997; 26: 623–630.

Crabtree B, Miller WL . Doing Qualitative Research, 2nd edN. Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1999.

Denzin N, Lincoln Y . Handbook of Qualitative Research, 2nd edN. Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA,. 2000.

Sandelowski M . The problem of rigor in qualitative research. ANS Adv Nurs Sci 1986; 8: 27–37.

Anderson KD, Friden J, Lieber RL . Acceptable benefits and risks associated with surgically improving arm function in individuals living with cervical spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 2009; 47: 334–338.

Gruen RL, Bragge P, Sedgman C, Pitt V, Chau M . An Environmental Scan of Traumatic Brain Injury and Spinal Cord Injury Research for the Victorian Transport Accident Commission (TAC): Summary of Findings. National Trauma Research Institute: Melbourne, Australia, 2011.

Liverman C, Altevogt B, Joy J, Johnson R,, Committee on Spinal Cord Injury Institute of Medicine Spinal Cord Injury: Progress, Promise and Priorities. Washington DC, USA, 2005.

Creasey G, McKenna S, Soril L, Samos C, Beekhuis G. . A Roadmap for Spinal Cord Injury: The Stanford Symposium on Regeneration, Repair and Restoration of Function After Spinal Cord Injury, 2012.

Weaver FM . Spinal Cord Injury QUERI Center 2012 Strategic Plan. Department of Veterans Affairs (DOVA): Illinois, USA. 2012.

Institute for Safety Compensation and Recovery Research Neurotrauma Research Strategy 2011—2015. Institute for Safety, Compensation and Recovery Research: Melbourne, Australia, 2012.

Boninger ML, Brienza D, Charlifue S, Chen YY, Curley KC, Graves DE et al. State of the Science Conference in Spinal Cord Injury Rehabilitation 2011: introduction. Spinal Cord 2012; 50: 342–343.

Heinemann AW, Steeves JD, Boninger M, Groah S, Sherwood AM . State of the Science in Spinal Cord Injury Rehabilitation 2011: informing a new research agenda. Spinal Cord 2012; 50: 390–397.

Adams M, Carlstedt T, Cavanagh J, Lemon RN, McKernan R, Priestley JV et al. International spinal research trust research strategy. III: A discussion document. Spinal Cord 2007; 45: 2–14.

Ramer MS, Harper GP, Bradbury EJ . Progress in spinal cord research—a refined strategy for the International Spinal Research Trust. Spinal Cord 2000; 38: 449–472.

Harper GP, Banyard PJ, Sharpe PC . The International Spinal Research Trust's strategic approach to the development of treatments for the repair of spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 1996; 34: 449–459.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the following people for their generous contribution to this project: Dr Naomi Kleitman, Craig H Neilson Foundation, California, USA; John Walsh AM, Magoo Actuarial Consulting, NSW, Australia; Pam Draganovic, La Trobe University, Victoria, Australia; Emma Donoghue, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia. This project was funded by the Victorian Transport Accident Commission and the Australian and New Zealand Spinal Cord Injury Network.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bragge, P., Piccenna, L., Middleton, J. et al. Developing a spinal cord injury research strategy using a structured process of evidence review and stakeholder dialogue. Part II: Background to a research strategy. Spinal Cord 53, 721–728 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2015.86

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2015.86

This article is cited by

-

Research priorities to enhance life for people with spinal cord injury: a Swedish priority setting partnership

Spinal Cord (2023)

-

What do we know about evidence-informed priority setting processes to set population-level health-research agendas: an overview of reviews

Bulletin of the National Research Centre (2022)

-

Ambulances are for emergencies: shifting attitudes through a research-informed behaviour change campaign

Health Research Policy and Systems (2019)

-

Work and SCI: a pilot randomized controlled study of an online resource for job-seekers with spinal cord dysfunction

Spinal Cord (2019)

-

It is a marathon rather than a sprint: an initial exploration of unmet needs and support preferences of caregivers of children with SCI

Spinal Cord (2018)