Abstract

Study design:

Cross-sectional study.

Objectives:

To establish whether inter-professional rehabilitation goals from people with non-traumatic spinal cord injury (SCI) can be classified against the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) SCI Comprehensive and Brief Core Sets early postacute situation.

Setting:

Neurological rehabilitation unit.

Methods:

Rehabilitation goals of 119 patients with mainly incomplete and non-traumatic SCIs were classified against the ICF SCI Core Sets following established linking rules.

Results:

A total of 119 patients generated 1509 goals with a mean (and s.d.) of 10.5 (9.1) goals per patient during the course of their inpatient rehabilitation stay. Classifying the 1509 rehabilitation goals against the Comprehensive ICF Core Set generated 2909 ICF codes. Only 69 goals (4.6%) were classified as ‘not definable (ND)’. Classifying the 1509 goals against the Brief ICF Core Set generated 2076 ICF codes. However, 751(49.8%) of these goals were classified as ‘ND’. In the majority of goals (95.7%), the ICF code description was not comprehensive enough to fully express the goals set in rehabilitation. In particular, the notion of quality of movement or specificity and measurability aspects of a goal (usually described with the criteria and acronyms SMART) could not be expressed through the ICF codes.

Conclusion:

Inter-professional rehabilitation goals can be broadly described by the ICF Comprehensive Core Set for SCI but not the Brief Core Set.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Spinal cord injuries may have profound effects on the physical functioning of an individual and cause activity limitations and participation restrictions.1 The level of lesion and the degree of neurological completeness/incompleteness influence the physical ability following a spinal lesion, but quality of life in spinal cord injury (SCI) is largely determined by activity and participation issues, such as personal care, community transportation and stable relationships.2 The ability to describe, classify and code information and measurements on such a broad range of health issues requires a common framework and language. The Word Health Organisation endorsed the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) as a member of the family of international classifications and was designed to provide such a framework; it aimed to ‘establish a common language for describing health-related states in order to improve communication’ (p3).3 The ICF understands human functioning to be the result of complex interactions between health conditions and environmental and personal factors.

Although the ICF is intended to be a document for use in clinical practice, its length and complexity make this a practical challenge. Tailored useful applications have therefore emerged and continue to be under development; the ICF should therefore be seen as a living tool.4 The need for such tailoring has led to the creation of condition-specific Core Sets5 that aim to contain a practically useful number of ICF codes, which are comprehensive enough to cover the range of health issues relevant to a particular condition.

Core Comprehensive and Brief Sets for individuals with SCI have been developed for the early postacute6 and the long-term situations.7 The Comprehensive early postacute Core Set consists of 162 ICF codes of which 63 are from ‘body functions’, 14 from ‘body structures’, 53 from ‘activities and participation’ and 32 from ‘environmental factors’. The Brief Set consists of 26 codes with 8 from ‘body functions’, 3 from ‘body structures’, 9 from ‘activities and participation’ and 5 from ‘environmental factors’. The Comprehensive Core Set has been validated for use by physiotherapists as well as occupational therapists who found that this Set covered the majority of patient problems they encountered.8, 9 More recently, Chen et al.10 developed an alternative Core Set as they felt that the existing ones were too influenced by western values and were not fully applicable to people from Asia who were seen as being more conservative and having closer family relationships.

Goal setting, defined as ‘the formal process whereby a rehabilitation professional or team together with the patient and/or their family negotiate goals',11 is widely practiced in rehabilitation settings even though its effectiveness has so far eluded formal unequivocal confirmation.12 The process of goal setting has been described as complex and frequently dominated by the professionals in the team.13 Challenging and yet achievable goals, frequently described with the acronym SMART (Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevent and Timed), have the potential to maximise the goal setting process.14 Attempts to classify patient goals against the ICF within the acute and postacute general rehabilitation settings have concluded that they broadly map against ICF domains.15, 16 Wallace et al.17 found that the goals of people with SCI are represented by the ICF, although they did not actually classify these goals against the Core SCI Sets. The aim of this study was therefore to specifically classify inter-professional rehabilitation goals from people with mostly non-traumatic and incomplete SCI against the ICF SCI Comprehensive and Brief Core Sets.

Materials and Methods

This study utilised anonymised data from a clinical database of 1458 patients admitted to an inpatient neuro-rehabilitation unit. The database18 contained diagnostic information, gender, age, length of stay, admission and discharge destination, rehabilitation goals and standardised clinical outcome measures (Barthel Index, Functional Independence Measure) of 1458 patients with a variety of neurological conditions admitted consecutively over a 13-year period.

From this database, we extracted the information of all 119 patients with a diagnosis of ‘SCI’ and classified their rehabilitation goals against the ICF SCI Comprehensive and Brief Core Sets. The rehabilitation goals are developed by the multi-disciplinary team in partnership with the patient, at weekly meetings. The process of goal planning broadly follows the principles described previously by others19, 20 and involves the agreement of relevant goals that are measureable, achievable and can be expressed in behavioural terms. These short- and long-term goals are reviewed on a two or three weekly basis, and the outcome of a goal is documented as either ‘Achieved’, ‘Not achieved’, ‘Ongoing’, ‘Goal revised’ or ‘Goal abandoned’.

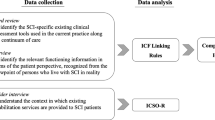

Classification of the goals followed the linking rules recommended by Cieza et al.21 involving the following steps:

-

Prior to classification, the researchers developed good knowledge of the conceptual and taxonomical fundaments of the ICF, as well as of the chapters, domains and categories of the detailed classification, including definitions.

-

Each individual goal was carefully inspected and analysed to ascertain the overall goal and divide the overall goal into a primary goal, a secondary goal aspect and a tertiary goal aspect as appropriate. For example, the overall goal ‘To walk to local shop, to purchase a newspaper’ was divided into the primary goal ‘To walk to local shop’ and the secondary goal aspect ‘to purchase a newspaper’.

-

Each primary, secondary and tertiary goal was then classified against the Comprehensive ICF Core Set for SCI—early postacute situation as well as the Brief ICF Core Set for SCI—early postacute situation.

This classification was conducted by two researchers (BH, JF) who independently classified a sub-sample of 40 goals. These were then compared and discussed to ensure a common interpretation. The remaining goals were then analysed independently, and any uncertainties or discrepancies were resolved by discussion.

-

The use of any assistive devices, orthoses, standing frames and so on described within a goal was identified by applying the ICF code ‘e115—Products and technology for personal use in daily living’.

-

Some goals required the support or assistance of another person, for direct physical assistance, facilitation, supervision or for giving prompts. In these cases, we added the ICF codes ‘e340—Personal care providers and personal assistants’ or ‘e355—Health professionals’ where this support was specifically provided by a health professional.

-

Where the content of a goal was more specific or precise than any of the available categories from a Core Set, we initially allocated the category that most closely matched the overall sentiment of the goal and then recorded that the precise nature of the goal could not be classified.

-

Where the content of a goal could not be matched against any of the available ICF codes from the Core Sets it was allocated ‘ND—not definable’.

Data analyses utilised descriptive statistics, providing frequency data of the goals against ICF domains of the component body functions, activities and participation and environmental factors from the SCI Core Sets. The frequency of goals, which could not be classified according to the existing codes, was also determined.

Results

The sample comprised 119 patients with a SCI diagnosis, 46 (38.7%) of whom were female. For the vast majority (114 or 95.8%), the underlying cause of their SCI was of a non-traumatic nature and included spinal tumours, cord compression and inflammation. In 45 patients (37.8%), the lesion was in the cervical area, and in 62 (52.1%) it was in the thoracic/lumbar area. For 12 (10.1%) patients, the database information was not clear enough to ascertain the precise level of lesion. A total of 102 (86.7%) patients had an incomplete lesion, and 8 (6.7%) had a complete lesion. For nine patients, the database information was not clear on their level of completeness. The mean (s.d., median, range) age on admission was 53.3 (16.4, 54.5, 67) years and their mean (s.d., median, range) length of stay was 43.6 (38.4, 36.0, 368) days. The median (interquartile range) Functional Independence Measure score on admission was 93.0 (34) and on discharge it was 113.0 (21). The median Barthel Index score on admission was 12.0 (9) and on discharge it was 18.0 (7).

These 119 patients generated 1509 goals with a mean (s.d.) of 10.5 (9.1) goals per patient during the course of their inpatient rehabilitation stay. Ninety-five of these goals had a secondary aspect and 5 also had a tertiary aspect. By the end of their stay, 1279 (77.7%) of these goals had been achieved, 154 (9.4%) had not been achieved, 45 (2.7%) were still ongoing, 13 (0.8%) had been revised and 18 (1.1%) were abandoned as they were inappropriate.

The majority of goals were multifaceted and were expressed through more than one ICF code; for example, the goal ‘to be transferring with minimal assistance from a nurse using a sliding board’ would have been expressed by three ICF codes (d420 for the transferring activity, e355 for the assistance provided by a health professional and e115 for the use of a product of personal use). Classifying the 1509 rehabilitation goals against the Comprehensive ICF Core Set therefore generated 2909 ICF codes. Only 69 goals (4.6%) were classified as ‘ND’. All 65 goals (95.7%) in the ICF SCI Core Sets were not specific enough to fully express the goals set in rehabilitation; for example, the goal ‘To transfer from sitting to standing, using my arms to push up and taking weight through my feet before taking hold of Carter Rollator’ (walking appliance) was classified as d420 (transferring oneself) and e120 (products and technology for personal indoor and outdoor mobility and transportation). However, the detailed description goes much beyond this simple code and expresses the notion of quality of achieving this transfer and the exact nature/type/brand of equipment to be used.

Classifying the goals against the Brief ICF Core Set generated 2076 ICF codes. However, 751 (49.8%) of these goals were classified as ‘ND’.

Table 1 provides a frequency breakdown of codes from the SCI Core Sets used against the 1509 rehabilitation goals from our sample.

When viewed against the major ICF categories, then our results showed that the rehabilitation goals set by the patients in our sample were mostly related to mobility (62.6%) or self-care (35.2%). In 510 (33.8%) goals, products and technology were used, and health professionals or other personal assistants had a significant role in achieving in 603 (40.0%) goals. Table 2 summarises the frequency (and the percentage) of codes from the Comprehensive ICF SCI Core Set against the major ICF domains.

Discussion

This study aimed to determine whether it was possible to classify rehabilitation goals against the ICF Core Sets for SCI. It enabled us to ascertain how many of these goals could be classified onto the ICF SCI Core Data Sets and therefore give an indication of how these Core Sets may reflect inpatient rehabilitation practice. Our findings suggest that for the vast majority of goals an appropriate code from the Comprehensive Core Set could be identified. This supports the findings by Herrmann et al.8, 9 who investigated the applicability of the ICF Core Sets for SCI to physiotherapy and occupational therapy practice and also by Mittrach et al.22 who concluded that goals of physiotherapy can be described with the language of the ICF.

Classification of goals against the Brief Core Set proved much more difficult, because there was no equivalent code for almost half of the goals. The usefulness of the Brief Core Set therefore seems limited within the context of rehabilitation goal setting. Others have also suggested that the Brief Core Sets for SCI reflect relevant areas of activity and participation in only a limited way and may require revision;23 alternatively categories from the Comprehensive Set could substitute insufficient Brief Core Set categories.6 Even though we were able to identify appropriate codes for the majority of goals, we found that in most cases the goal description was more extensive or more specific than the ICF codes permitted. In many cases, an ICF code ending in ‘8’ or ‘9’ (‘other specified’ or ‘unspecified’) could have been used. However, the use of these codes ending in 8/9 has been specifically discouraged in the ICF linking rules.21 Additional elements, beyond the broad goal topic (such as transferring, walking or dressing), were embedded in the goal.v. These elements would contribute to making the goals SMART,14 by adding specificity on the activity, any support or equipment needed, the time frame and quantification of the performance. In line with the aims of clinical practice, goals also focussed on enhancing the ‘quality’ of movement, making reference to good posture, expected movement sequence or appropriate weight bearing. This supports the notion that rehabilitation goals are often educational in nature, making explicit to the patient ‘how to’ achieve particular tasks. Barnard et al.13 described the process of goal setting as being heavily influenced by members of the rehabilitation team, particularly when describing the quality standards of a goal. This quality element seems less important to the developers of the ICF; it is possible that it represents a unique priority for therapists involved in rehabilitation, although this has yet to be investigated.

The focus of the vast majority of goals was related to activity and participation issues of mobility (62.6%), self-care (35.2%) and domestic life (13.9%). These were similar priorities as found by some24, 25 but not to others.26, 27 In particular, goals relating to employment, leisure activity and personal relationships were infrequent in our sample. Patients at a later stage of their rehabilitation journey, or following return to the community, may well have a greater interest in these areas.

Very few goals (0.5%) focussed on the impairment level, which aims at improving individual body structures or individual body functions. Wallace et al.17 also found that activity and participation goals were a key focus for individuals with SCI at the transition from hospital to home.

Most of the patients in our sample had an incomplete SCI of non-traumatic origin. Therefore, our findings may not generalise to individuals with complete lesions of traumatic origin. They may therefore also not generalise to patients who undergo rehabilitation in a specialist SCI centre.28 Our investigation was based on a retrospective analysis of rehabilitation goals against the language of the ICF. The goals in our sample were not necessarily written with a full knowledge of the ICF or the desire to use the language of the ICF by either the patients or the multi-disciplinary team members. Therefore, goals set with the specific intent to utilise the language of the ICF may have produced a much better match. There seems merit in a more standardised use of the ICF language when setting goals, as this may facilitate better comparisons of outcomes. However, using a standardised language should not limit the content of goal setting, particularly relating to the specificity of such goals.

Data archiving

There were no data to deposit.

References

Carpenter C, Forwell SJ, Jongbloed LE, Backman CL . Community participation after spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2007; 88: 427–433.

Chang F-H, Wang Y-H, Jang Y, Wang C-W . Factors associated with quality of life among people with spinal cord injury: application of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health model. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2012; 93: 2264–2270.

World Health Organisation. International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF). World Health Organisation: Geneva, Switzerland. 2001.

Kostanjsek N . Use of The International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) as a conceptual framework and common language for disability statistics and health information systems. BMC Public Health 2011; 11: S3.

Stucki G, Cieza A, Ewert T, Kostanjsek N, Chatterji S, Bedirhan T . Application of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) in clinical practice. Disabil Rehabil 2002; 24: 281–282.

Kirchberger I, Cieza A, Biering-Sørensen F, Baumberger M, Charlifue S, Post MW et al. ICF core sets for individuals with spinal cord injury in the early post-acute context. Spinal Cord 2010; 48: 297–304.

Cieza A, Kirchberger I, Biering-Sørensen F, Baumberger M, Charlifue S, Post MW et al. ICF Core Sets for individuals with spinal cord injury in the long-term context. Spinal Cord 2010; 48: 305–312.

Herrmann KH, Kirchberger I, Stucki G, Cieza A . The Comprehensive ICF core sets for spinal cord injury from the perspective of physical therapists: a worldwide validation study using the Delphi technique. Spinal Cord 2011; 49: 502–514.

Herrmann KH, Kirchberger I, Stucki G, Cieza A . The comprehensive ICF core sets for spinal cord injury from the perspective of occupational therapists: a worldwide validation study using the Delphi technique. Spinal Cord 2011; 49: 600–613.

Chen H-C, Yen T-H, Chang K-H, Lin Y-N, Wang Y-H, Liou T-H et al. Developing an ICF core set for sub-acute stages of spinal cord injury in Taiwan: a preliminary study. Disabil Rehabil 2015; 37: 51–55.

Wade DT . Goal setting in rehabilitation: an overview of what, why and how. Clin Rehabil 2009; 23: 291–295.

Levack WMM, Taylor K, Siegert RJ, Dean SG, McPherson KM, Weatherall M . Is goal planning in rehabilitation effective? A systematic review. Clin Rehabil 2006; 20: 739–755.

Barnard Ra, Cruice MN, Playford ED . Strategies used in the pursuit of achievability during goal setting in rehabilitation. Qual Health Res 2010; 20: 239–250.

Bovend’Eerdt TJH, Botell RE, Wade DT . Writing SMART rehabilitation goals and achieving goal attainment scaling: a practical guide. Clin Rehabil 2009; 23: 352–361.

Lohmann S, Decker J, Müller M, Strobl R, Grill E . The ICF forms a useful framework for classifying individual patient goals in post-acute rehabilitation. J Rehabil Med 2011; 43: 151–155.

Huber EO, Tobler A, Gloor-Juzi T, Grill E, Gubler-Gut B . The ICF as a way to specify goals and to assess the outcome of physiotherapeutic interventions in the acute hospital. J Rehabil Med 2011; 43: 174–177.

Wallace MA, Kendall MB . Transitional rehabilitation goals for people with spinal cord injury. Disabil Rehabil 2014; 36: 642–650.

Freeman Ja, Hobart JC, Playford ED, Undy B, Thompson AJ . Evaluating neurorehabilitation: lessons from routine data collection. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2005; 76: 723–728.

Schut HA, Stam HJ . Goals in rehabilitation teamwork. Disabil Rehabil 1994; 16: 223–226.

Holliday RC, Cano S, Freeman JA, Playford ED . Should patients participate in clinical decision making? An optimised balance block design controlled study of goal setting in a rehabilitation unit. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2007; 78: 576–580.

Cieza A, Geyh S, Chatterji S, Kostanjsek N, Ustün B, Stucki G . ICF linking rules: an update based on lessons learned. J Rehabil Med 2005; 37: 212–218.

Mittrach R, Grill E, Walchner-Bonjean M, Scheuringer M, Boldt C, Huber EO et al. Goals of physiotherapy interventions can be described using the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health. Physiotherapy 2008; 94: 150–157.

Ballert C, Oberhauser C, Biering-Sørensen F, Stucki G, Cieza A . Explanatory power does not equal clinical importance: study of the use of the Brief ICF Core Sets for spinal cord injury with a purely statistical approach. Spinal Cord 2012; 50: 734–739.

Byrnes M, Beilby J, Ray P, McLennan R, Ker J, Schug S . Patient-focused goal planning process and outcome after spinal cord injury rehabilitation: quantitative and qualitative audit. Clin Rehabil 2012; 26: 1141–1149.

Hosseini SM, Oyster ML, Kirby RL, Harrington AL, Boninger ML . Manual wheelchair skills capacity predicts quality of life and community integration in persons with spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2012; 93: 2237–2243.

Simpson LA, Eng JJ, Hsieh JTC, Wolfe DL . The health and life priorities of individuals with spinal cord injury: a systematic review. J Neurotrauma 2012; 29: 1548–1555.

Hammell KW . Quality of life among people with high spinal cord injury living in the community. Spinal Cord 2004; 42: 607–620.

Van der Putten J, Stevenson V, Playford E, Thompson A . Factors affecting functional outcome in patients with nontraumatic spinal cord lesions after inpatient rehabilitation. Neurorehabil Neural Repair 2001, 99–104.

Acknowledgements

Dr Diane Playford was supported by the National Institute for Health Research University College London Hospitals Biomedical Research Centre.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Haas, B., Playford, E., Ahmad, A. et al. Rehabilitation goals of people with spinal cord injuries can be classified against the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health Core Set for spinal cord injuries. Spinal Cord 54, 324–328 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2015.155

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2015.155