Abstract

Study design:

Case report and review of the literature.

Objectives:

Myxopapillary ependymoma (MPE) is a relatively rare glioma that develops from the spinal part of the filum terminale, usually in adulthood. While it is generally benign, MPE can disseminate intraspinally, and this malignant behavior requires a multidisciplinary response with surgery and radiotherapy. We report here a case of MPE occurring in the lumbosacral spine area of an 8-year-old boy.

Setting:

Japan, Tokyo.

Methods:

We report here a case of MPE, treated with subtotal surgical resection followed by craniospinal irradiation (CSI), in an 8-year-old boy. The patient was referred to our hospital with a 6-month history of severe pain in the lower back and legs, paralysis of the legs and dysuria. Magnetic resonance imaging images showed a large tumor that filled the entire spinal canal below L1. After subtotal resection of the tumor, the pathological findings established a diagnosis of MPE. Since the tumor had perforated its capsule, increasing the risk of intraspinal dissemination, the patient underwent radiotherapy and CSI after surgery.

Results:

Magnetic resonance images obtained 3 years after the surgery did not show any recurrence of MPE.

Conclusion:

Although tumor resection followed by CSI can be considered an effective strategy for treating a child with MPE, long-term follow-up is necessary to ensure early detection of any local recurrence or dissemination of the tumor, or of post-radiotherapy scoliosis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Myxopapillary ependymoma (MPE) is a relatively rare encapsulated glioma, WHO grade I, originating from the spinal part of the filum terminale. Although MPEs in the cauda equina region are generally slow-growing and benign, they often recur locally if incompletely resected or if the tumor capsule is perforated.1 MPEs can also disseminate intraspinally.

Case presentation

History and examination

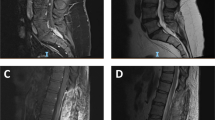

An otherwise healthy 8-year-old boy was referred to our hospital, when he developed dysuria after a 6-month history of pain in the lower back and legs. He had difficulty in standing and walking, and his abdomen was distended due to retaining urine in the bladder. Plain X-ray images revealed extensive scalloping of the posterior wall of the vertebral bodies at the lumbosacral region (Figure 1a). Magnetic resonance (MR) images findings established a diagnosis of neuroparalysis caused by a cauda equina tumor filling the spinal canal from L1 to S3 (Figures 1b and c). There was no tumor in the other spinal canal space and a brain.

Preoperative lumbar sagittal MR images: (a): T1-weighted; (b): T2-weighted; (c): Gd-DTPA. C inset: an axial image from the L3 level (indicated by the line in the right panel). Arrows indicate a very large tumor filling the spinal canal, with a low signal from L1 to S3 on the T1-weighted images, high signal on the T2-weighted images and non-uniform uptake on the Gd−DTPA contrast images. The patient's abdomen is distended due to urinary retention.

Operation and postoperative course

We performed a hemilaminectomy at the left side from L1 to S1, exposing the dura mater. The tumor was carefully removed using an ultrasonic surgical aspirator, and gross total removal was achieved macroscopically. Since the tumor capsule perforated, we considered subtotal resection. The patient experienced significant relief from the lower back and leg pain immediately after surgery. Pathological examination revealed that the overall tumor morphology was consistent with MPE (Figure 2). The MIB1 index was 1%. The patient underwent postoperative craniospinal irradiation (CSI) at a dose of 24.3 Gy (1.5 Gy per fraction: 5 days; 1.2 Gy per fraction: 14 days) and localized radiotherapy at a dose of 16 Gy (2 Gy per fraction: 8 days), with a total dose of 40.3 Gy. When the patient was discharged 8 weeks after the surgery, he was almost entirely free of the original neurological symptoms. Magnetic resonance images obtained 3 years later showed no evidence of local recurrence or intraspinal tumor dissemination, as there was no deformity of the lumbar spine.

Photomicrographs of surgical specimens stained with H & E (a), and immunostained for vimentin (b), glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) (c), and S100 (d). H & E staining shows hyperplasic tumor cells with circular/elliptical nuclei and mucinous stroma. Specific staining indicating the presence of GFAP, vimentin and S100 led to a diagnosis of myxopapillary ependymoma. (Scale bar=150 μm).

Discussion

MPE, which was first reported by Kernohan in 1932, is relatively rare. Childhood onset of spinal MPE is even more rare. Only six cases have been previously reported in which a patient under 15 years of age received CSI to treat MPE.2, 3, 4 Our patient is the youngest to undergo subtotal resection and CSI for MPE. Although surgical resection is the first choice of treatment for MPE, a multidisciplinary approach using radiotherapy or chemotherapy is required to prevent local recurrence and intraspinal dissemination if the tumor capsule has been perforated.1 Nakamura et al.1 reported that a radiotherapy dose of 40–50 Gy may prevent MPE dissemination and local recurrence in adults (mean age, 33 years) when the tumor cannot be completely resected and intraspinal dissemination is suspected.

Of the 6 reported cases of children who were treated with CSI for MPE when less than 15 years old, four received CSI as part of the initial treatment strategy because meningeal dissemination and distal metastasis were already present, and complete resection was impossible (Table 1).2, 3, 4 One of these four patients died of an unrelated cause, and another experienced a recurrence of the tumor. However, tumor progression was suppressed in the other two patients. Therefore, we concluded that a sufficient dose of postoperative CSI might prevent local recurrence and intraspinal dissemination of MPE, even in children.2, 3, 4 In two cases, children were treated with CSI when MPE recurred despite complete resection.2, 3 Therefore, we recommend including postoperative CSI as part of the initial treatment strategy if the tumor capsule is perforated, as in our patient’s case, or if there is even the slightest suspicion of intraspinal dissemination.

In children, who have not yet reached skeletal maturity, CSI's long-term side effects may include spinal deformities. Reports of MPE in children have not discussed spinal deformities following treatment. To minimize the risk of CSI-related spinal deformities in this 8-year-old boy, we chose to perform a left hemilaminectomy. Although Naganawa et al.5 reported that no spinal kyphosis deformities developed during an 8-year follow-up period in 20 patients (mean age, 43 years) who underwent hemilaminectomy, our patient was a child who had not yet reached skeletal maturity, and who had received a total radiation dose of 40.3 Gy. Thus, careful observation for the onset of any spinal deformities is particularly important for this patient.

Conclusion

We reported here a case of MPE occurring in the lumbosacral spine area of an 8-year-old boy. At 3-year follow-up, the patient's side effects have been mild and he is progressing well. However, we are continuing to follow him to detect local tumor recurrence, intraspinal dissemination or indications of post-radiotherapy scoliosis.

References

Nakamura M, Ishii K, Watanabe K, Tsuji T, Matsumoto M, Toyama Y et al. Long-term surgical outcomes for myxopapillary ependymomas of the Cauda Equina. Spine 2009; 34: E756–E760.

Al-Halabi H, Montes JL, Atkinson J, Farmer JP, Freeman CR . Adjuvant radiotherapy in the treatment of pediatric myxopapillary ependymomas. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2010; 55: 639–643.

Chinn DM, Donaldson SS, Dahl GV, Wilson JD, Huhn SL, Fisher PG . Management of children with metastatic spinal myxopapillary ependymoma using craniospinal irradiation. Med Pediatr Oncol 2000; 35: 443–445.

Merchant TE, Kiehna EN, Thompson SJ, Heideman R, Sanford RA, Kun LE . Pediatric low-grade and ependymal spinal cord tumors. Pediatr Neurosurg 2000; 32: 30–36.

Naganawa T, Miyamoto K, Hosoe H, Suzuki N, Shimizu K . Hemilaminectomy for removal of extramedullary or extradural spinal cord tumors: medium to long-term clinical outcomes. Yonsei Med J 2011; 52: 121–129.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Disclaimer

No portion of this paper has been presented previously.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Shirasawa, H., Ishii, K., Iwanami, A. et al. Pediatric myxopapillary ependymoma treated with subtotal resection and radiation therapy: a case report and review of the literature. Spinal Cord 52 (Suppl 2), S18–S20 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2014.95

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2014.95