Abstract

Study design:

Qualitative study using individual in-depth interviews.

Objectives:

The objective of this study was to explore the factors influencing the choice of bladder management for male patients with spinal cord injury (SCI).

Setting:

Public hospitals in Malaysia.

Methods:

Semistructured (one-on-one) interviews of 17 patients with SCI; 7 were in-patients with a recent injury and 10 lived in the community. All had a neurogenic bladder and were on various methods of bladder drainage. Interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim and analyzed using thematic analyses.

Results:

The choice of bladder management was influenced by treatment attributes, patients’ physical and psychological attributes, health practitioners’ influences and social attributes. Participants were more likely to choose a treatment option that was perceived to be convenient to execute and helped maintain continence. The influence of potential treatment complications on decision making was more variable. Health professionals’ and peers’ opinions on treatment options had a significant influence on participants’ decision. In addition, patients’ choices depended on their physical ability to carry out the task, the level of family support received and the anticipated level of social activities. Psychological factors such as embarrassment with using urine bags, confidence in self-catheterization and satisfaction with the current method also influenced the choice of bladder management method.

Conclusion:

The choice of bladder management in people with SCI is influenced by a variety of factors and must be individualized. Health professionals should consider these factors when supporting patients in making decisions about their treatment options.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In people with spinal cord injury (SCI), there is an increased risk of urinary tract deterioration, giving rise to significant morbidity and mortality.1 Health professionals often emphasize the clinical importance of appropriate bladder management and stringent surveillance of renal functions to prevent these complications. Despite medical advances, conservative management remains the mainstay of bladder management,2 and the common options are the following: clean intermittent catheterization (CIC), either self or assisted, indwelling catheterization, either transurethrally (IDUC) or suprapubically (SPC), and spontaneous voiding.3

The choice of a bladder management method should take into consideration factors such as patients’ age, functional status, preference, motivation and cost.4, 5 Existing clinical practice guidelines list the indications for each treatment option but do not guide the health professionals on how to help patients deliberate the risks and benefits of each of these options.1, 6 This is particularly important in decisions where there is clinical equipoise in supporting one treatment option over another.4, 7

In Malaysia, the four options mentioned above are widely available in general public hospital. Owing to the lack of resources, urodynamic study is not routinely performed during the initial admission. Most patients use disposable polyvinyl catheter for CIC. Suprapubic and urethral catheters are changed every 2 to 6 weeks, depending on the type of catheter. Family members are taught how to change suprapubic catheter at home, but for urethral catheter, it is usually carried out in a health facility for fear of urethral injury. The surgeon decides whether suprapubic catheter insertion needs to be carried out under general or local anesthesia.

Previous studies have noted that patients changed their bladder management over time and suggested that incontinence, obesity, autonomic dysreflexia, spasticity, dependency, accessibility and clothing influence are among some contributing factors.3, 5 Most were retrospective studies, and to the authors’ knowledge, there is no study that explicitly looked at the decision-making process of people with SCI when choosing a treatment for bladder management. By understanding these factors, health professionals would be in a better position to engage patients in shared decision making. Patients who are actively involved in decision making have better knowledge of treatment options, a more accurate expectation of possible benefits and harms, lower decisional conflicts and make choices that are consistent with their values.8 Therefore, this study aimed to explore factors that influence patients’ decisions when choosing a type of bladder management.

Materials and methods

This study used a qualitative methodology to provide an accurate description and interpretation of the decision-making process from the perspective of patients with SCI.9

Participants

Seventeen participants with SCI were recruited from five hospitals in Malaysia that offer spinal rehabilitation services (Table 1). A purposeful sampling technique10 was used to achieve maximum variations in terms of age, level of disability, method of bladder drainage, duration of injury and stage of decision making. Inclusion criteria were the following: patients with traumatic SCI (either paraplegia or tetraplegia with complete or incomplete injury), neurogenic bladder, Malaysian, male and ability to speak either English or Malay. We excluded patients who had a cognitive impairment. Patients attending the outpatient spinal clinics and those admitted for spinal rehabilitation were screened for eligibility. Except for one participant who refused to participate owing to logistic difficulties, all 17 who were approached agreed to participate.

Data collection

Between May and December 2012, semistructured interviews were conducted by two of the researchers (JPE and CJN), using an interview topic guide (Box 1). Development of the interview guide was based on the conflict theory of decision-making,11 the author’s (JPE) experience in working with people who have SCI, opinions of experts in the field of decision making and issues identified from the literature. Interviews were conducted until data saturation was reached, that is, ‘a point reached during data collection when no new themes or issues arise within a category of data’.12 All interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim and checked. Memos were used to document any relevant impressions, spontaneous ideas, evaluations, solutions and thoughts after each interview and throughout the analyses. The duration of the interviews ranged from 23 to 75 min.

Analysis

The NVivo qualitative software package (version 10; QSR International Pty Ltd, Doncaster, VIC, Australia) was used to manage the data, which were analyzed thematically using an approach described by Braun and Clarke.13 The analysis focused on the reasons why the patients chose or rejected a particular treatment option or changed their bladder management method. JPE read the transcripts repeatedly to familiarize herself with the data. Labeling individual phrases or paragraphs with descriptive codes that reflect the meaning of the data generated the initial codes. The codes that were conceptually similar were grouped into categories and were constantly compared within and across transcripts. The coding framework was revised iteratively until the team agreed on the final framework, which was then used to code the rest of the transcripts. The final process involved defining and naming the themes.

Reflections and data trustworthiness

JPE is a female rehabilitation physician with 6 years of experience in managing patients with SCI; as a novice qualitative researcher, this study is part of her PhD project. CJN and WYL are her PhD supervisors and are experienced qualitative researchers in the field of medical decision making. A number of steps were taken to ensure data trustworthiness. In-depth interviews allowed prolonged engagements with the participants, which enabled the researcher to gain the participants’ trust and better understand the research field. The researchers also kept records of all analysis decisions, kept a reflective journal and maintained the verbatim quotations throughout all stages of analysis. Emerging codes and categories were constantly critiqued and challenged by CJN and WYL to reduce potential bias during data interpretation by JPE.

Statement of ethics

Both University Malaya Medical Centre Medical Ethics Committee (878.7) and The Ministry of Health Medical Research Ethics Committee (NMRR-12-91-10850) approved the study. We certify that all applicable institutional and government regulation regarding the ethical use of human volunteers were followed during the course of this research. Written consent was obtained from all participants.

Results

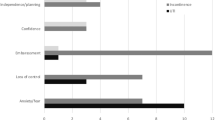

The factors influencing a patient’s choice of a bladder management method were classified into broad categories: treatment attributes, patient attributes (physical and psychological), health professionals’ influences and social attributes (Table 2). Illustrative quotes that support the themes are presented in Boxes 2, 3,4,56.

Treatment attributes

Treatments that were perceived to be convenient to execute and offer continence appealed to participants. However, the impact of the potential treatment complications on their decision was more variable (Box 2).

Convenience

The participants interpreted the concept of ‘convenience’ differently. What appeared to be a convenient treatment option by a patient might be considered as inconvenient by another. For instance, some participants considered the frequent catheterization in CIC as troublesome and chose IDUC instead. For this group, carrying a urine bag was considered convenient, as the urine bag could store large amounts of urine. On the other hand, those who chose CIC viewed regular catheterization as an act that disciplined them and perceived the urine bag as ‘annoying’ and the presence of tubing restrictive to their mobility. The ability to change a suprapubic catheter at home by family members was considered convenient compared with IDUC, which required travelling to a health facility.

Continence

The ability of a particular treatment option to maintain continence was an important consideration when making a decision. Patients were more likely to accept occasional incontinence; however, when the continence became more frequent, they would opt for another method of bladder management.

Treatment harm

When making a decision, almost all participants were concerned about renal disease, but the reactions to other complications (urinary tract infections, urethral injury and surgical complications) were more variable. Many considered IDUC, CIC and SPC to be protective against renal disease, whereas spontaneous voiding was felt to be an unsafe option. Past experience in handling these complications and doctors’ reassurance helped to alleviate these concerns. Participants who refused SPC viewed the procedure as painful, particularly among those who had recent surgeries. Although the patients’ main reasons for avoiding SPC were fear of complications, they were unclear about the nature of complications. There was a misperception that SPC surgery involved the genitalia.

Patients’ physical attributes

Physical disability

Participants cited impaired hand function, body imbalance and impaired transfer skills as reasons not to choose CIC (Box 3). As they regained these functions over time, their bladder management method preference tended to change.

Sexuality and fertility

Concerns about sexuality and fertility did not emerge spontaneously unless the researchers probed the issues. At the early stage of the injury, having sex and children were not priorities and did not influence the choice of bladder drainage. The importance of these functions became more evident at later stages of their illnesses when they began to think about having a relationship and marriage.

Patients’ psychological attributes

Embarrassment

Participants were embarrassed to carry a urine bag and were concerned about the stigma (Box 4). Those who chose this method also shared the same sentiment but coped with it by hiding the urine bag.

Confidence in catheterization

Participants’ decision to use CIC was not only affected by the confidence in performing catheterization themselves but also whether they trusted their caregiver to perform the task. There was fear that an inexperienced caregiver would inflict pain and injury to them during the catheterization.

Satisfaction

The satisfaction that participants had with their current method reinforced their belief that it was the best choice for them, whereas dissatisfaction made them discontinue the method and seek another treatment option.

Health professionals’ influences

Opinions on treatment options

Participants tended to respect and concur with the health professionals’ expert opinions on the treatment recommendation, even when they were not fully informed of the treatment options and their risks and benefits (Box 5). At times, patients were instructed by the doctors to choose a particular treatment option without first asking their preference.

At early stages of injury, patients with SCI were overwhelmed with many competing concerns, and bladder management was often not their priority. In addition, most had no prior knowledge about SCI. As a result, they often followed their doctors’ recommendations when making the decision. However, this did not apply when SPC was recommended; other factors such as fear of surgery and peers’ opinions had a greater influence on the participants’ decisions compared with the doctors’ opinions.

Support

The degree of support provided to the patients by the doctors influenced the participants’ treatment choices. Discussing the decision over several sessions and using educational materials helped the patients to make decisions.

Social attributes

Peers’ opinions and experiences

Peers with bladder problems had a substantial influence on patients’ decisions and could, at times, over-ride doctors’ recommendations (Box 6). Observing their peers performing a particular bladder drainage method had a significant impact on the participant’s decision. Similarly, being surrounded by peers using a different method of bladder management might lead them to choose that method. Similarly, the information that participants gathered from their experienced SCI peers served as an impetus to help them decide whether to accept a particular treatment option.

Family support

This study did not find that family support had a direct influence on the patients’ decision-making process. Participants felt that their families were not knowledgeable about their condition, and some felt uncomfortable discussing bladder drainage methods with their family, because it was perceived as something private. However, participants did consider the burden of care their choices might have on their family and choose methods that were the easiest for their families to manage.

Social activities

The level of social activities in which the patient was likely to be engaged is a factor to consider when making decisions about treatment options. Participants would choose an option that they perceived would allow them to participate in their social activities. When the patients were not involved actively in social activities, they were willing to tolerate the disadvantages of a particular treatment option.

Discussion

This qualitative study provides insight into the factors that influence decision making in people with SCI. Through interviews, the participants expressed how the treatment attributes, health professionals’ preferences, and their physical, social and psychological status influenced their decisions.

This study highlights how people with SCI give different emphases to medical complications associated with treatment options, which in turn determine their choice of bladder drainage method. The information provided by health professionals, participants’ preinjury perceptions about disability and bladder problems and previous experience all contribute to the participants’ views regarding these complications. Therefore, it is important for health professionals to explore patients’ perceptions of treatment complications and provide accurate information, especially during the early phases of their illnesses.

Following SCI, survivors are usually confined to an environment with which they are unfamiliar, and this often excludes them from making decisions about their own treatment.14, 15 Similar to a previous study, we found that participants trust and rarely question the information they receive from health professionals,16 impelling them to simply agree with what was recommended. Health professionals should be aware of this imbalanced power relationship and make an attempt to create an environment in which patients are able to make informed choices with minimal influence from health professionals. One way to achieve this would be to ensure that patients receive accurate and balanced information about the treatment options and their benefits and risks. In this study, some participants who made decisions based on insufficient information and misperceptions decided to change their method of bladder management at a later time. Such a change normally occurred when the patient experienced adverse effects of the chosen treatment option. This result not only causes psychological distress to the patient but also wastes resources for retraining patients.

Peers’ influences on participants’ decisions in this study echoed the results of previous studies that described peer support as indispensable when peers have experience with SCI.17, 18 In this study, peer support seemed to influence those who were making decisions about SPC. It is likely that our participants did not receive adequate information and support when they were asked to consider SPC. A previous study reported that SPC users’ initial negative experiences were due to inadequate preparation and support from health professionals.19

It was rather unexpected that, in this study, there was a lack of involvement of the family in the patients’ decision-making process. SCI is known to cause emotional and physical stress to family members, and many are involved in caregiving responsibilities. Thus, it would be natural to assume that their opinions are valued when making treatment decisions.20 It could be that our participants considered bladder management as something private, which consequently hindered family involvement. More studies are needed to define the role of the family in decision making, across different contexts and cultures.

As evident from this study, the ability of patients to imagine their future activities influenced the choice of bladder drainage. SCI survivors encountered difficulties to move forward and needed time to rediscover their new selves.21 In the case of bladder management, it might be necessary to help them visualize the possible social activities in which they are likely to engage and how different methods of bladder drainage may facilitate or hinder those activities. Once these individuals have chosen a method, it is equally important to educate them on how to manage the entire procedure not only in the community but also at home and in the office. For instance, in CIC, in addition to emphasizing the ability to self-catheterize, the health professionals should counsel patients on how they could independently prepare the catheterization equipment, discard the urine and manage the consequences of leaking, such as changing soiled clothes and linens. Patients who are managed in hospitals are likely to overlook these tasks, as most of these are carried out by hospital aids.

Clinical implications

This study describes the importance of how the particular treatment, the attributes of patients and health professionals and social factors affect the decision-making process of patients with SCI. Patients also trust the information they receive from health professionals and use it to help them make decisions. It is, therefore, crucial for health professionals to provide sufficient high-quality information and explore what is important to SCI patients when assisting them in making decisions that are congruent with their values. At the time of this study, there were no structured health education programmes on bladder management options at any study sites. Future patient education programmes should include the provisions of accurate and balanced information on the treatment options and their risks and benefits. Health professionals should be trained on how to support patients in decision making using effective communication skills or decision support tools, such as patient decision aids.8 The important role that peers play in the decision-making process suggests that having a platform for patients to connect with their peers is beneficial.

Limitations and strengths

This study has a few limitations. First, decision making is a dynamic process that occurs over time. By interviewing participants at a particular stage of illness may not provide a full picture of their decision-making process. Future studies should consider conducting multiple interviews with each participant over time. Other methods of data collection, such as observation and clinical record analysis, might also be helpful. Second, the patients interviewed were from a tertiary hospital with rehabilitation facilities, and thus the findings may not be transferrable to those in different settings where the options are not identical. The variations in clinical settings, health-care policies and cultural beliefs on bladder-related diseases and disabilities may also make some of the findings non-transferable.

The strength of this study is it is one of the few studies that capture the experiences of patients with SCI in the decision-making process. The sampling technique enabled us to capture patients at the point of decision making as well as those with experience. This approach provides information at the time of decision making as well as retrospectively.

Conclusion

Participants’ encounters with health professionals and interactions with peers have important roles in the decision-making process. Patients’ physical, psychological and social attributes influence their choice of bladder management. Health professionals should consider these factors when supporting patients in making decisions about their treatment options.

Data Archiving

There were no data to deposit.

References

Wolfe DL, Ethans K, Hill D, Hsieh JTC, Mehta S, Teasell RW et al. Bladder health and function following spinal cord injury. In: Eng JJ, Teasell RW, Miller WC, Wolfe DL, Townson AF, Hsieh JHC, et al (eds). Spinal Cord Injury Rehabilitation Evidence. Vancouver. 2010 pp 1–19.

Wyndaele JJ, Madersbacher H, Kovindha A . Conservative treatment of the neuropathic bladder in spinal cord injured patients. Spinal Cord 2001; 39: 294–300.

Cameron AP, Wallner LP, Tate DG, Sarma AV, Rodriguez GM, Clemens JQ . Bladder management after spinal cord injury in the United States 1972 to 2005. J Urol 2010; 184: 213–217.

El-Masri WS, Chong T, Kyriakider AE, Wang D . Long-term follow-up study of outcomes of bladder management in spinal cord injury patients under the care of the Midlands Centre for Spinal Injuries in Oswestry. Spinal Cord 2012; 50: 14–21.

Yavuzer G, Gok H, Tuncer S, Soygur T, Arikan N, Arasil T . Compliance with bladder management in spinal cord injury patients. Spinal Cord 2000; 38: 762–765.

Abrams P, Agarwal M, Drake M, El-Masri W, Fulford S, Reids S et al. A proposed guideline for the urological management of patients with spinal cord injury. BJU Int 2008; 101: 989–994.

Jamison J, Maguire S, McCann J . Catheter policies for management of long term voiding problems in adults with neurogenic bladder disorders. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011; 12: CD004375.

Stacey D, Bennett C, Barry MJ, Col NF, Eden KB, Holmes-Rovner M et al. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011; 10: CD001431.

Sandelowski M . Focus on research methods. Whatever happened to qualitative description? Res Nurs Health 2000; 23: 334–340.

Creswell JW, Plano Clark VL (eds). Collecting data in mixed methods research. In:. Designing and Conducting Mixed Method Research. Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA. 2011 pp 173–174.

Janis IL, Mann L . A conflict model of decision making. In:. Decision Making: A Psychological Analysis of Conflict, Choice and Commitment. Free Press: New York, NY, USA. 1977 pp 45–80.

Morse J . Designing funded qualitative research. In: Denzin N, Lincoln Y (eds). Handbook for Qualitative Research. Sage Publication: Thousand Oaks, CA. 1994 pp 220–235.

Braun V, Clarke V . Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 2006; 3: 77–101.

Sand Å, Karlberg I, Kreuter M . Spinal cord injured persons’ conceptions of hospital care, rehabilitation, and a new life situation. Scand J Occup Ther 2006; 13: 183–192.

Pellatt GC . Patient–professional partnership in spinal injury rehabilitation. Br J Nurs 2004; 13: 948–953.

Burkell JA, Wolfe DL, Potter PJ, Jutai JW . Information needs and information sources of individuals living with spinal cord injury. Health Info Libr J 2006; 23: 257–265.

Veith EM, Sherman JE, Pellino TA, Yasui NY . Qualitative analysis of the peer mentoring relationship among individuals with spinal cord injury. Rehabil Psychol 2006; 51: 289–298.

Haas BM, Price L, Freeman JA . Qualitative evaluation of a community peer support service for people with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 2013; 51: 295–299.

Sweeney A, Harrington A, Button D . Suprapubic catheters: a shared understanding, from the other side looking. J Wound Ostomy Continenence Nurs 2007; 34: 418–424.

Bergmark BA, Winograd CH, Koopman C . Residence and quality of life determinants for adults with tetraplegia of traumatic spinal cord injury etiology. Spinal Cord 2008; 46: 684–689.

Carpenter C . The experience of spinal cord injury: The individual’s perspective-Implications for rehabilitation practice. Phys Ther 1994; 74: 614–628.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Director of Health Malaysia for permission to publish this paper. The study was funded by the BKP Grant from University of Malaya, Malaysia (BKP002-2012A).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Engkasan, J., Ng, C. & Low, W. Factors influencing bladder management in male patients with spinal cord injury: a qualitative study. Spinal Cord 52, 157–162 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2013.145

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2013.145

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Experiences of people with spinal cord injuries readmitted for continence-related complications: a qualitative descriptive study

Spinal Cord (2024)

-

Pulse article: survey of neurogenic bladder management in spinal cord injury patients around the world

Spinal Cord Series and Cases (2021)

-

Stigma and self-management: an Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis of the impact of chronic recurrent urinary tract infections after spinal cord injury

Spinal Cord Series and Cases (2018)

-

Current and future international patterns of care of neurogenic bladder after spinal cord injury

World Journal of Urology (2018)

-

Associations with being physically active and the achievement of WHO recommendations on physical activity in people with spinal cord injury

Spinal Cord (2017)