Abstract

Study design:

Retrospective database analysis.

Objectives:

To describe comorbidities, pain-related pharmacotherapy, healthcare resource use and costs among patients with spinal cord injury (SCI) newly prescribed pregabalin.

Setting:

United Kingdom (UK).

Methods:

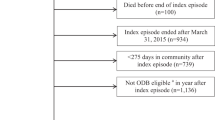

Using The Health Improvement Network database, SCI patients newly prescribed (index event) pregabalin (N=72; average age 48 years; 53% female) were selected. Study measures were evaluated during both the 9-months pre-index and follow-up periods.

Results:

Prevalent comorbidities included musculoskeletal disorders (51.4%), digestive disorders (23.6%) and urogenital disorders (20.8%). Opioids were the most frequently prescribed medications (pre-index, 58.3%; follow-up, 61.1%, P=not significant (NS)) followed by nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugss (43.1 and 45.8%, P=NS). Use of anti-epileptics (other than pregabalin) recommended for SCI neuropathic pain decreased (25.0 vs 12.5%, P=0.0290), whereas sedative/hypnotic use (18.1 vs 26.4%, P=0.034) increased during follow-up. Over 50% of patients had visits to specialists, and at least 1 in every 10 had laboratory/radiology-related visits. There were numerical decreases in proportions of patients with emergency room visits (22.2 vs 13.9%, P=NS) and hospitalizations (16.7 vs 12.5%, P=NS) during follow-up. Medication costs were higher during follow-up (median, £561.4 vs £889.5, P<0.0001). Costs of outpatient visits were similar during both study periods (£1082.1 vs £1066.1) as were total medical costs (£1689.0 vs £2169.4) when costs of pregabalin prescriptions were excluded. Inclusion of pregabalin costs resulted in higher (P<0.0001) total medical costs during follow-up.

Conclusion:

SCI patients had a high comorbidity, medication and healthcare resource use burden in clinical practice. Further research with larger sample sizes and more comprehensive data sources may serve to clarify study findings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Neuropathic pain (NeP), caused by a lesion or disease of the somatosensory nervous system, occurs in up to 50% of patients with spinal cord injury (SCI).1, 2, 3, 4 Pain is recognized as a primary driver of impaired patient functioning, quality of life and sleep in patients with SCI.5, 6 Although NeP following SCI (SCI-NeP) is common, it is notably difficult to manage and seldom resolves in the long term. Traditional analgesics are of limited value; however, there is evidence to support the use of pregabalin followed by amitriptyline, gabapentin and tramadol.7, 8

It is hypothesized that the effectiveness of pregabalin in the treatment of SCI-NeP is due to its effect on spontaneous and evoked neuronal hyperactivity/hyperexcitability. Pregabalin is purported to interact with voltage-gated N-type calcium ion channels at the α2-δ subunit in central nervous system neuronal tissues and with the NDMA receptor.9 Consequently, pregabalin reduces the release of neurotransmitters (such as glutamate in hyperexcited neurons) and causes a decrease in the transmission of nociceptive signals. Pregabalin is approved in the European Union for the treatment of central and peripheral NeP, general anxiety disorder, and as an adjunctive therapy in partial seizures. Pregabalin was also significantly more effective than placebo in two randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trials in patients with SCI-NeP.10, 11

Although a recent systematic review reported on the efficacy/effectiveness of medications for the treatment of SCI-NeP,7 and the costs associated with hospitalization and acute rehabilitation after SCI have been summarized,12 there is limited published literature quantifying the overall and specific costs associated with treating SCI-NeP patients in clinical practice after the initial hospitalization/rehabilitation phase. A recent study described annual direct medical costs (inpatient and outpatient) associated with the ‘postacute phase of care’ in SCI patients in the United States.13 However, similar data on costs associated with pain medications or costs of community-based care for SCI patients in the United Kingdom are unavailable. Thus, the overall goal of this study was to examine the prevalence of comorbidities, pain-related treatment patterns, healthcare resource utilization and direct medical costs in patients with SCI prescribed pregabalin in general practice settings in the United Kingdom.

Materials and methods

Data source and sample selection

Data for the study were obtained from the UK THIN (The Health Improvement Network) database. THIN comprises anonymized medical records from 429 general practices in the United Kingdom representing 7.7 million patients and includes data on patient characteristics (for example, age and gender), diagnoses and details of prescribed medications (for example, quantity dispensed and dosage). All records for each patient are linkable with a unique encrypted patient identifier to create a longitudinal record of the patient’s healthcare resource use during the period of evaluation.

All patients ⩾18 years old with a diagnosis of SCI (diagnoses codes presented in Table 1) on or after 1 July 2004, who initiated treatment with pregabalin at least 9 months after the SCI diagnosis (date of the first pregabalin prescription was designated as the index date) and who were continuously enrolled during the 9-month pre-index and follow-up periods were selected. Patients with missing data for age or gender were excluded. Patients with a diagnosis of seizure disorder were also excluded to ensure that SCI patients in the study were prescribed pregabalin for NeP.

Measures and analyses

Demographic characteristics and prevalence of comorbidities

Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients prescribed pregabalin were assessed and included average age, gender distribution and co-prevalence of selected comorbidities, including mental disorders, sleep disorders, cardiovascular disorders, digestive disorders, musculoskeletal disorders, urogenital disorders, metabolic disorders and pulmonary disorders.

Pain-related pharmacotherapy

Percent exposure (proportions of patients) and magnitude of use (number of prescriptions) were evaluated for medication classes recommended for the treatment of SCI-NeP based on clinical evidence,7, 8, 14 for medications commonly used to treat NeP and associated sequelae. The number of prescriptions, days of therapy and average daily costs of pregabalin were determined during the follow-up period. Compliance with pregabalin treatment was evaluated in patients who received at least two pregabalin prescriptions during follow-up using the Medication Possession Ration (MPR) and Proportion of Days Covered (PDC) measures. MPR was defined as total days supply (excluding days supply of last prescription)/total days between first and last prescription; MPR cutoffs were set at ⩾80%=good compliance and <80%=poor compliance. PDC was defined as total days supply/total number of days in the post-index study period. Persistence with pregabalin therapy was defined as the median number of days from the start date of the first pregabalin prescription until a gap of at least 30 days in therapy occurred.

Healthcare resource utilization and direct medical costs

Healthcare resource use (proportions of patients using resources and magnitude of use) was evaluated during the pre-index and follow-up periods, and included outpatient visits (general practitioners (GPs), specialists, laboratory/radiology and other outpatient services), emergency room (ER) visits and hospitalizations.

Direct medical costs associated with the use of medications, non-pharmacologic therapies, surgical procedures and interventions, outpatient and ER visits and total medical costs during both study periods were also determined. Costs associated with ER visits, non-pharmacological therapies, and surgical interventions and procedures were included only to the extent to which they were available in THIN. As THIN predominantly captures care delivered in GP practices, a majority of these costs are not represented in the total medical costs.

Costs of medications were determined using UK drug prices provided through the Multilex drug knowledge base from First Databank (FDB, Exeter, UK) and costs of other healthcare resources were determined based on reference cost fee schedules published by the UK National Health Service (NHS) and private insurance companies in the United Kingdom. All assigned costs were for the year 2011.

Statistics

Descriptive statistics (numbers and percents for categorical variables; means with s.d.’s and medians with interquartile ranges for continuous variables) were used to evaluate the different variables as appropriate. McNemar or Wilcoxon sign-rank tests were used to determine the statistical significance of within-group changes between the pre-index and follow-up periods. All analyses were performed using the SAS software system, PC version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, USA). The study protocol was approved by the Scientific Review Committee, which has been approved by the NHS South-East Multicenter Research Ethics Committee.

Results

Demographic characteristics and prevalence of comorbidities

A total of 72 patients satisfied all the study entry criteria and were included in the analysis. Demographic characteristics and clinical comorbidities of study patients are presented in Table 2. On average, patients were 48 (s.d.=13.1) years old and 52.8% were female. The median duration between the SCI diagnosis and the first pregabalin prescription was 326 days. Nearly three out of every four patients (72.2%) had at least one of the evaluated comorbidities; the most prevalent types of comorbidities were musculoskeletal disorders (51.4%), digestive disorders (23.6%) and urogenital disorders (20.8%).

Pain-related treatment patterns

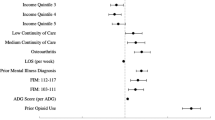

The proportions of patients who received ⩾1 prescription(s) for the various study medication classes are presented in Table 3 and the magnitude of use is presented in Table 4. Patients were characterized by a high burden of medications recommended for SCI-NeP, and those medications used to treat NeP and associated sequelae in both the pre-index and follow-up periods.

Opioids were the most frequently prescribed medications in both periods (pre-index, 58.3% and follow-up, 61.1%), followed by nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (43.1 and 45.8%, respectively), and analgesics recommended for SCI-NeP (44.4 and 40.3%, respectively). The proportions of patients who received anti-epileptics (other than pregabalin) recommended for SCI-NeP (25.0 vs 12.5%, P=0.0290) decreased significantly, whereas the proportions of patients who received sedative/hypnotics (18.1 vs 26.4%, P=0.0338) increased from pre-index to follow-up. More than 80% of patients received at least three of the evaluated medication classes in both the pre-index and follow-up periods.

During the pre-index period, among patients who received the various study medications, the magnitude of use was the highest for selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and strong opioids (a median of eight prescriptions each), followed by sedative/hypnotics (median, 6), muscle relaxants and weak opioids (both medians, 5). In the follow-up period, among users of the various medications, the magnitude of use was the highest for selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (median, 10), followed by strong opioids (median, 9.5), serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (median, 9), muscle relaxants (median, 8) and sedative/hypnotics (median, 6).

Patients received an average of 7.5 (s.d.=6.1, median=8) pregabalin prescriptions in the follow-up period; the average days of therapy with pregabalin were 243.6 days (s.d.=204.7, median=231) and the average daily cost of pregabalin was £3.0 (s.d.=£1.2, median=£2.6). Compliance with pregabalin therapy was high, the average MPR was 87.4% (s.d.=20.8%), and three out of every four patients (76.2%) had an MPR ⩾80%; the average PDC was 77.6% (s.d.=28.4%) and nearly two-thirds of patients (61.9%) had a PDC of ⩾80%. Persistence with pregabalin therapy, defined as the median time until a 30-day gap in therapy, was 141.5 days (mean=164 days and s.d.=114.2 days).

Healthcare resource use and direct medical costs

The proportions of patients who received the various healthcare services and the magnitude of service use during the study period are presented in Table 5. As THIN is a GP database, all study patients had visits to a GP during both the pre-index and follow-up periods. Over half had visits to specialists and at least 1 out of every 10 patients had laboratory procedure or radiology-related visits. There were numerical decreases (albeit not statistically significant) in proportions of patients with ER visits (22.2 vs 13.9%) and hospitalizations (16.7 vs 12.5%) in the follow-up period. The magnitude of healthcare resource use was substantial in both the pre-index and follow-up periods, with patients having a median of 17 GP visits and 3 visits with specialists in both periods.

Total medication costs, mean (median), were higher (P<0.0001) in the follow-up period (Table 6): pre-index, £1091.9 (£561.4) vs follow-up, £1483.6 (£889.5). Costs of outpatient visits were similar during both study periods (£1390 (£1082.1) vs £1352.6 (£1066.1)) as were total direct medical costs (£2528.6 (£1689.0) vs £2882.5 (£2169.4)) when costs of pregabalin were excluded. However, inclusion of pregabalin costs resulted in significantly higher (P<0.0001) total medical costs in the follow-up period (£3580.7 (£2896.7)). Costs of GP visits comprised the majority of the costs associated with total outpatient visits and medication costs accounted for over a third of the total direct medical costs in both study periods.

Discussion

Pain in SCI patients is notably difficult to manage and often refractory to treatment.7 Our study was the first to evaluate patterns of pain-related pharmacotherapy, healthcare resource use and direct medical costs in SCI patients receiving care in general practice settings in the United Kingdom. Our results suggest that SCI patients initiating treatment with pregabalin had a high comorbidity burden, over half of the patients had musculoskeletal disorders, and consistent with the pathophysiology of SCI (disrupted autonomic control of the gastrointestinal tract, decreased mobility and lack of sensation), the prevalence of comorbidities related to bladder and bowel dysfunction was also high.

Use of medications that are recommended or commonly used for the treatment of SCI-NeP7, 8, 14 was substantial and consistent with other chronic pain populations; opioids and NSAIDs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; were the most frequently prescribed treatments. Polypharmacy with pain-related medications noted in our study is not surprising given the high observed prevalence of musculoskeletal pain conditions in study patients. Moreover, because of this high co-prevalence of other pain comorbidities, and because physicians′ prescribing notes including the specific reason for prescribing each medication is not available in THIN, it is possible that the pain medication use patterns in our study are only partially reflective of SCI-NeP, and that these medications were in theory being prescribed for other noted pain comorbidities. However, we excluded patients with seizure disorders, and none of the study patients had general anxiety disorder, thus it is reasonable to conclude that pregabalin use in our study was largely related to SCI-NeP. There was no evidence of use of several therapies recommended for SCI-NeP including anti-spasticity medications, cannabinoids and intrathecal injections in our study. As THIN is a GP database, it is conceivable that these treatments were prescribed or administered (or both) by specialists in the United Kingdom and accordingly are not reflected in THIN.

Sample sizes in our study were too small to detect any notable changes in patterns of pharmacotherapy following the initiation of pregabalin treatment. Use of other anti-epileptics recommended for SCI-NeP decreased likely because these medications were replaced by pregabalin during follow-up. Conversely, use of sedative/hypnotics increased. Although this finding is puzzling, it conceivably represents the natural progression of comorbidities including sleep impairment in SCI patients rather than being related to pregabalin treatment. Compliance with pregabalin in SCI patients (MPR, 87% and PDC, 78%) was higher than compliance rates for pregabalin reported in patients with other chronic pain conditions, including diabetic neuropathy (DPN), PDC 47%;15 and fibromyalgia (FM), MPR, 79%,16 and PDC between 52 and 59%.17, 18 Persistence with pregabalin therapy was also higher (median=141.5 days, mean=164 days) than reported in patients with DPN (mean between 87 days and 113 days)15, 19 and FM (median 90 days).18 Such adherence to therapy may be considered a combined surrogate for efficacy and tolerability, as patients who continue on a therapy generally do so because it is effective and well tolerated, or conversely, the drug is not being discontinued for adverse events or lack of efficacy. These observations are worth further investigation with regard to outcomes and other factors that may contribute to adherence.

Resource use was substantial in both study periods with a median of 17 GP visits and over half of study patients seeking specialist care. The observed high rate of specialist consultation is consistent with the myriad of comorbid illnesses potentially requiring specialist supervision in SCI patients. Although we were unable to detect significant changes in resource use, there were numerical decreases in percent use in several resource use categories following initiation of pregabalin treatment, a finding worthy of further investigation.

Medication costs were higher in the follow-up period, primarily driven by initiation of pregabalin. In both periods, medication costs accounted for a large proportion of the total direct costs; however, this proportion is likely to be overstated given that ER visits, hospitalizations, surgical interventions and alternative treatments are not adequately captured in THIN. Consequently a majority of these costs, which are purported to be particularly high in SCI patients, could not be determined. Reported costs of ER visits are limited to the cost of an ER physician consultation, but costs of care delivered during the ER encounter, which are likely to constitute the majority of ER-related costs, were not available. Thus, the true direct medical costs of patients with SCI-NeP in general practice settings are underestimated in our study.

The interpretation of our findings is limited by the unavailability of physician prescribing notes in THIN or patient outcome measures including changes in pain severity levels, patient functioning and quality of life. Thus, it is not possible to determine the precise indications for which pain-related treatments were prescribed nor the effects of any prescribed treatments on patient outcomes. Accordingly, we could not ascertain whether pregabalin therapy resulted in an improvement in patient outcomes, thereby off-setting, at least partially, the increased costs of pregabalin treatment. Moreover, because specialists do not contribute data directly to THIN, SCI-NeP management that occurs outside of GP practices (including medical costs associated with this care) are not reflected in our study. We chose THIN despite these limitations because it is the largest source of real-world data in the United Kingdom where pregabalin is approved for a broad NeP indication, and accordingly, THIN was the best available data source for evaluating pregabalin use in SCI patients in community-based settings.

In conclusion, our study is the first to describe patterns of pain-related pharmacotherapy and healthcare resource use and costs in patients with SCI initiating treatment with an evidenced-based medication for the treatment of NeP in clinical practice in the United Kingdom. Our results indicate that SCI patients have a significant comorbidity, medication and healthcare resource use burden, and costs associated with treating these patients in clinical practice are significant. Although our study findings are largely descriptive and preliminary, they provide the best available evidence to date, and represent an essential first step towards a full understanding of the subject. Further research should include use of larger sample sizes and more comprehensive data sources to clarify these valuable initial findings, and more detailed investigation of the relationships among adherence to pregabalin, clinical outcomes and costs.

Data archiving

There were no data to deposit.

References

Eide PK . Pathophysiological mechanisms of central neuropathic pain after spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 1998; 36: 601–612.

Siddall PJ, McClelland JM, Rutkowski SB, Cousins MJ . A longitudinal study of the prevalence and characteristics of pain in the first 5 years following spinal cord injury. Pain 2003; 103: 249–257.

Norrbrink Budh C, Lund I, Ertzgaard P, Holtz A, Hultling C, Levi R et al Pain in a Swedish spinal cord injury population. Clin Rehabil 2003; 17: 685–690.

Werhagen L, Budh CN, Hultling C, Molander C . Neuropathic pain after traumatic spinal cord injury-relations to gender, spinal level, completeness, and age at the time of injury. Spinal Cord 2004; 42: 665–673.

Jensen MP, Kuehn CM, Amtmann D, Cardenas DD . Symptom burden in persons with spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2007; 88: 638–645.

Norrbrink Budh C, Hultling C, Lundeberg T . Quality of sleep in individuals with spinal cord injury: a comparison between patients with and without pain. Spinal Cord 2005; 43: 85–95.

Teasell RW, Mehta S, Aubut JA, Foulon B, Wolfe DL, Hsieh JT et al Spinal Cord Injury Rehabilitation Evidence Research Team. A systematic review of pharmacologic treatments of pain after spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2010; 91: 816–831.

Finnerup NB, Baastrup C . Spinal cord injury pain: mechanisms and management. Curr Pain Headache Rep 2012; 16: 207–216.

Lyrica (package insert) Pfizer Inc: New York, NY. 2007.

Siddall PJ, Cousins MJ, Otte A, Griesing T, Chambers R, Murphy TK . Pregabalin in central neuropathic pain associated with spinal cord injury: a placebo-controlled trial. Neurology 2006; 67: 1792–1800.

Vranken JH, Dijkgraaf MG, Kruis MR, Van der Vegt MH, Hollmann MW, Heesen M . Pregabalin in patients with central neuropathic pain: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of a flexible-dose regimen. Pain 2008; 136: 150–157.

Priebe MM, Chiodo AE, Scelza WM, Kirshblum SC, Wuermser LA, Ho CH . Spinal cord injury medicine. 6. Economic and societal issues in spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2007; 88: S84–S88.

French DD, Campbell RR, Sabharwal S, Nelson AL, Palacios PA, Gavin-Dreschnack D . Health care costs for patients with chronic spinal cord injury in the Veterans Health Administration. J Spinal Cord Med 2007; 30: 477–481.

Heutink M, Post MW, Wollaars MM, van Asbeck FW . Chronic spinal cord injury pain: pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatments and treatment effectiveness. Disabil Rehabil 2011; 33: 433–440.

Udall M, Harnett J, Mardekian J . Costs of pregabalin or gabapentin for painful diabetic peripheral neuropathy. J Med Econ 2012; 15: 361–370.

Gore M, Sadosky A, Zlateva G, Clauw DJ . Clinical characteristics, pharmacotherapy and healthcare resource use among patients with fibromyalgia newly prescribed gabapentin or pregabalin. Pain Pract 2009; 9: 363–374.

Burke JP, Sanchez RJ, Joshi AV, Cappelleri JC, Kulakodlu M, Halpern R . Health care costs in patients with fibromyalgia on pregabalin vs duloxetine. Pain Pract 2012; 12: 14–22.

Kleinman NL, Sanchez RJ, Lynch WD, Cappelleri JC, Beren IA, Joshi AV . Health outcomes and costs among employees with fibromyalgia treated with pregabalin vs standard of care. Pain Pract 2011; 11: 540–551.

Margolis J, Cao Z, Fowler R, Harnett J, Sanchez RJ, Mardekian J et al Evaluation of healthcare resource utilization and costs in employees with pain associated with diabetic peripheral neuropathy treated with pregabalin or duloxetine. J Med Econ 2010; 13: 738–747.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr Stephen McMahon (London Pain Consortium, King’s College London, UK) for his review and feedback regarding the study sample definition. Dr McMahon was not financially compensated for his collaboration on this project or development of this manuscript. This study was sponsored by Pfizer Inc.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Dr Gore is Principal Consultant, Kei-Sing Tai is Principal Statistician and Christopher George Rice is Research Associate at Avalon Health Solutions, Inc., who were paid consultants to Pfizer in connection with the development and execution of both this manuscript and the research it describes. Dr Gore also owns stock in Pfizer. Drs Sadosky, Cappelleri and Mardekian are all employees of Pfizer and own stock in Pfizer. Drs Finnerup and Nieshoff were not financially compensated for their collaboration on this project or development of this manuscript. Dr Finnerup received funding from the European Investigational Medicines Initiative, which is a public–private partnership between the pharmaceutical industry (including Pfizer) and the European Union.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Gore, M., Brix Finnerup, N., Sadosky, A. et al. Pain-related pharmacotherapy, healthcare resource use and costs in spinal cord injury patients prescribed pregabalin. Spinal Cord 51, 126–133 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2012.97

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2012.97

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Evaluation of methods to estimate missing days’ supply within pharmacy data of the Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD) and The Health Improvement Network (THIN)

European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology (2017)