Abstract

Study design:

A case of a very rare type of schwannoma is reported. It is the sixth reported case of intramedullary melanotic schwannoma and the only one localized in the conus.

Methods:

A 56-year-old woman was treated in this department for a C5–C6 spondylodiscitis. After 6 months her arms showed a rapid recovery, but her incomplete flaccid paraplegia remained stable. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with gadolinium enhancement of the lumbar tract revealed an intramedullary lesion at the level of Th12–L1. During surgery, an intramedullary, poorly vascularized, dark gray lesion was detected and was totally removed. One year after surgery, no recurrence was encountered and the patient showed significant improvement.

Conclusion:

It had previously been hypothesized that intramedullary melanotic schwannomas originate from the rostral components of the neural tube. This case presented a different localization with respect to the previously described cases, all localized in the cervical or high thoracic tracts, and thus uncertainties are raised about the previous hypotheses. Nevertheless, it is agreed that total surgical removal is the best treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Intramedullary schwannomas are rare, with only 57 cases described in the literature.1 The sixth reported case of intramedullary melanotic schwannoma is presented. The interest of this case lies in its peculiarity of being localized inside the conus medullaris.2, 3, 4, 5, 6 Since a few hypothesis regarding intramedullary melanotic schwannomas' origin were previously advanced, their applicability to this case is verified.

Case report

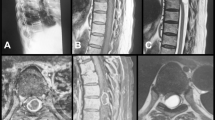

A 56-year-old woman with C5–C6 spondylodiscitis that had rapidly caused quadriplegia (ASIA B, C3), including urinary retention, had been surgically treated. Spondylo-discectomy (C4–C7) followed by arthrodesis and kyphosis correction had been performed. The same infection had also caused endocarditis. After 45 days of antibiotic therapy, the patient neurologically improved and the heart infection healed. Six months later, since the lower limbs were not improving correspondingly to her arms, a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with gadolinium enhancement of the lumbar tract was performed, and an intramedullary lesion at the level of Th12–L1 was found (Figure 1).

Surgery

A Th12 laminectomy was sufficient to expose the entire lesion. Duramater and arachnoid sheath were opened longitudinally (Figures 2a and b). A total progressive microscopic piece-meal removal was performed by dissecting the tumor from the adherent surrounding spinal cord. The approximately 3 × 4-cm lesion was dark gray, poorly vascularized, prevalently intramedullar and partially emerging into the posterior surface. Total removal of the lesion was verified by postoperative MRI (Figure 3). MRI performed 12 months after surgery showed no recurrence and the patient regained the ability to walk with a cane. Her urinary functions recovered.

Histopathological features

Surgical specimen, consisting of about 35-mm fragments, was routinely fixed in neutral buffered formol and embedded in paraffin. Some 5-μm sections were stained with hematoxylin–eosin and additional 5-μm sections of the most representative specimen were mounted on electrostatic slides and used for immunohistochemical study (standard streptavidin–biotin peroxidase method). The primary antibodies used were as follows: monoclonal antibody direct against HMB-45, melan-A, vimentin, Ki-67, polyclonal antibody against S-100 protein. Light microscopy revealed a highly cellular tumor composed of densely pigmented spindle cells. The neoplastic cells were isomorphous and were arranged in a swirling pattern. The nuclei were oval and sometimes vesicular. The cytoplasm was eosinophilic and frequently contained pigment in the form of fine or coarse granules. The lesion did not show necrosis and mitosis were exceedingly rare. Brown pigmented nerve fibers embedded in a fibrous stroma were also found. Immunohistochemical study showed diffuse HMB-45, melan-A, vimentin and S-100 immunocoloration both in the lesion and in the nervous root. Proliferation index, as determined by estimating the percentage of the Ki-67-positive cells of the total number of neoplastic cells, was less than 1%. Morphological appearance (Figure 4), along with immunohistochemical profile, agreed with diagnosis of melanotic schwannoma.

(a–d) Light-microscopy findings of melanotic schwannoma. Monotonous proliferation of spindle-shaped cells arranged in a fascicular pattern without necrosis and mitoses (a); the cytoplasm is filled with pigment (a, b) and pigmented nerve roots (c, d). Original magnifications: × 10 (a, b); × 5 (c); × 20 (d). Staining, hematoxylin–eosin (a–d).

Discussion

The results of a detailed revision of the literature, including intramedullary melanotic schwannoma presentation, duration of symptoms, location, treatment and outcome, are illustrated in Table 1.

Few authors have advanced theories regarding the origin of this rarely encountered tumor, including a co-origin with melanotic schwannomas of the peripheral nerves.4 It is known that peripheral nerve melanotic schwannomas are malignant in 10% of the cases and recur in 24% especially when partially resected.4 This may be due either to an abnormal differentiation of neural crest cells into melanogenetic Schwann cells at the origin, or to a later melanomatous transformation of schwannomas.4 Since the origin of the lesion in the previously described cases was cervical or high thoracic, it has been proposed that the tumor may originate from the rostral components of the neural tube.4

The previously described cases were surgically treated in four cases, of which three did not show recurrence (cases 1, 2 and 4 in Table 1) whereas one (case 3 in Table 1) showed aggressiveness and contiguous invasion requiring radiotherapy and re-operation. In only one case was needle aspiration performed.

The case of intramedullary melanotic schwannoma described in this report presented a peculiar localization (conus medullaris). This contradicts the previously advanced hypothesis, which suggests that its origin is from the rostral components of the neural tube. The second peculiarity of this case is its uncommon clinical presentation following a cervical spondylodiscitis.

Similar to the majority of the previously described types of treatment, total removal was performed and no recurrence was found at 1-year follow-up.

Conclusion

This study proves that melanotic schwannomas may be localized in the conus medullaris, which weakens the previous theories regarding its origin and its peculiar localization in the cervical or high thoracic tracts. The best treatment consists of total surgical removal followed by imaging controls to confirm the absence of recurrence.

References

Conti P, Pansini G, Mouchaty H, Capuano C, Conti R . Spinal neurinomas: retrospective analysis and long-term outcome of 179 consecutively operated cases and review of the literature. Surg Neurol 2004; 61: 35–44.

Acciarri N, Padovani R, Riccioni L . Intramedullary melanotic schwannoma: report of a case and review of the literature. Br J Neurosurg 1999; 13: 322–325.

Marchese MJ, McDonald JV . Intramedullary melanotic schwannoma of the cervical spinal cord: report of a case. Surg Neurol 1990; 33: 353–355.

Santaguida C, Sabbagh AJ, Guiot MC, Del Maestro RF . Aggressive intramedullary melanotic schwannoma: case report. Neurosurgery 2004; 55: 1430–1434.

Sola-Pérez J, Pérez-Guillermo M, Bas-Bernal A, Giménez-Bascuñana A, Montes-Clavero C . Melanocytic schwannoma: the cytologic aspect in fine-needle aspiration cytology (FNAC). Diagn Cytopathol 1994; 11: 291–296.

Solomon RA, Handler MS, Sedelli RV, Stein BM . Intramedullary melanotic schwannoma of cervicomedullary junction. Neurosurgery 1987; 20: 36–38.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mouchaty, H., Conti, R., Buccoliero, A. et al. Intramedullary melanotic schwannoma of the conus medullaris: a case report. Spinal Cord 46, 703–706 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2008.9

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2008.9

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Intramedullary schwannoma of conus medullaris: rare site for a common tumor with review of literature

Spinal Cord Series and Cases (2018)

-

Invasive intramedullary melanotic schwannoma: case report and review of the literature

European Spine Journal (2018)