Abstract

Two dimensional polymers have emerged in recent years as useful materials for the development of catalysts for future energy demand. However, the synthesis of ultrathin organic two dimensional polymers is still limited and further development is necessary. Here we present the synthesis of nanometer-thick two-dimensional (2D) porphyrin polymer nanodisks via the exfoliation of covalent organic frameworks, and evaluate their performance in the hydrogen evolution reaction under irradiation with broadband light. The nanodisks are synthesized through the simultaneous axial coordination of pyridines and metal ions to produce 2D porphyrin nanodisks of 1 nm average thickness. Importantly, the polymer composite with platinum-reduced graphene oxide exhibits hydrogen evolution activity upon irradiation with visible and NIR light. These results represent the use of 2D ultrathin polymer nanodisks derived from covalent organic frameworks in heterogeneous photocatalytic processes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

wo-dimensional (2D) materials, such as chalcogenides, graphene1, and organic polymers2,3,4,5, have recently received significant attention due to their unique electronic and photochemical properties. In order to obtain these 2D materials in bulk, the exfoliation of layered materials in the liquid phase is one of the simplest synthetic procedures6,7,8. Meanwhile, covalent organic frameworks (COFs)9,10,11 have also recently been employed as starting materials for exfoliation into multiply-layered 2D polymers in the liquid phase12,13. For example, Zamora et al. reported a sonication procedure for the exfoliation of COFs into nano-sized layered structures14,15. More recently, Dichtel et al. reported that polar solvents, such as dioxane, water, and N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF), exfoliate COFs16. However, most of these previous studies showed that the exfoliated COFs, comprised of 1,3,5-triphenylbenzene unit, still possess structures with several layers. It is still unclear whether or not it is possible to exfoliate COFs composed of π-conjugated molecules such as porphyrins for the synthesis of 2D polymer nanodisks. Feng and Wang et al. reported the exfoliation of anthraquinone COFs using a ball milling method to produce 5 nm-thick redox active COFs as cathodes for lithium-ion battery17. Banerjee et al. reported the novel method to exfoliate COFs using a Diels-Alder reaction of N-hexylmaleimide and anthracene in COFs to exfoliate into the nanosheets12. Consequently, the further development of exfoliation methods is necessary to realize the rational syntheses of sub-nanometer- thick 2D π-conjugated ultrathin polymer nanodisks18,19.

Porphyrins are unique molecules in terms of their photochemical properties and structural diversities7,20. Not surprisingly, they have been employed as building blocks for COFs and have demonstrated carrier-transport as well as electro-catalytic properties10,21,22. Despite this, less is still known about the possible exfoliation of porphyrin COFs and their rational design applications.

In the present study, we report an exfoliation method for COFs composed of porphyrin molecules through the incorporation of metal ions and the use of axial ligands to disrupt the π-π stacking of the porphyrin COFs via steric hindrance. We observe the clear formation of uniform nanometer-thick disk-like dispersed macro-molecular structures using copper as the metal ion and 4-ethylpyridine as the axial ligand. Furthermore, we describe the photocatalytic activity of these structures for H2 generation under irradiation with visible and near-infrared (NIR) light23,24,25,26,27,28,29.

Results

Exfoliation design in porphyrin covalent organic framework

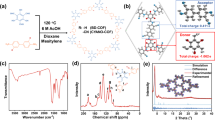

In order to exfoliate the COFs into two-dimensional (2D) polymer layers (referred as to exfoliated nanodisks in this study), we proposed that the coordination of axial ligands at the porphyrin centers of the COFs would disrupt the π-π interactions between the 2D-COF layers, resulting exfoliation (Fig. 1a). In this study, we employed the stable porphyrin-containing COFs (DhaTph) reported by Banerjee et al30. due to its chemical stability in solvents, a consequence of intramolecular hydrogen bonding. As axial ligands for exfoliation, we chose pyridines (i.e., pyridine size: 3.8 Å) to disrupt a π-π stacking (∼4 Å) between DhaTph layers. The DhaTph was built using the 5,10,15,20-tetrakis(4-aminophenyl)-21H,23H-porphyrin (Tph, 1) unit, and the 2,5-dihydroxyterephthalaldehyde (Dha, 2) linker unit. The DhaTph was synthesized through the formation of the Schiff-base between the amine (−NH2) of 1 and the aldehydes of 2 in the presence of acetic acid (CH3COOH), as previously described30. Detailed synthesis conditions and the chemical structures of the building blocks are shown in Supplementary Fig. 1. As reported by Banerjee et al. and Jiang et al., DhaTph is chemically stable due to the intramolecular hydrogen bonding within its planer surfaces30,31.

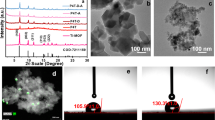

Strategy for the simultaneous exfoliation of the DhaTph and exfoliation using pyridine ligands. a Scheme for the synthesis of exfoliated DhaTph. The addition of metals and axial ligands induces exfoliation of the covalent organic frameworks composed of porphyrin units. b Chemical structures of DhaTph and pyridines. c The PXRD spectra of the DhaTph (black), e-CON(Cu, py) (cyan), e-CON(Cu, mpy) (pink), and e-CON(Cu, epy) (orange) (λ = 1.5418 Å)

The powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD, α = 1.5418 Å) pattern of DhaTph exhibited an intense peak at 2θ = 3.5° corresponding to diffraction of the (100) plane of the square lattice, with a d value of 25 Å (Fig. 1b). Minor diffraction peaks at 2θ = 7.1° and 22° correspond to (200) and (001) diffractions, respectively. Hence, the distance between the porphyrin layers is estimated to be approximately 4 Å based on the (001) planes, which is consistent with that reported by Banerjee et al30. The Fourier-transform infrared (FT-IR) spectrum of DhaTph acquired in attenuated total reflectance (ATR) mode exhibited a peak at 1612 cm−1, which corresponds to the imine (−C = N) stretching vibration of the linker (Supplementary Fig. 2). The FTIR spectra of monomers (1 and 2) are shown in Supplementary Fig. 3 for comparison. The scanning electron microscopy (SEM) image of the as-prepared DhaTph reveals a clumped morphology (Fig. 2). To quantitatively determine the width and height of DhaTph, we used atomic force microscopy (AFM) in tapping mode (Supplementary Fig. 4 and Supplementary Table 1). In order to perform the AFM experiments, DhaTph was firstly sonicated in DMF or ethanol for 10 min and spin coated onto a freshly prepared mica substrate. The thickness and width of DhaTph were determined to be 8.6 ± 3.4 nm and 162.9 ± 69.4 nm (n = 30, averaged value ± range of the distribution from 30 individual counts was shown in the following AFM measurement results), respectively. In the following section, we discuss the exfoliation of DhaTph through the simultaneous incorporation of metal ions and axial ligands in order to explore the exfoliation hypothesis presented above.

Structural analysis of e-CON(Cu, epy). a Scanning electron microscopy image of e-CON(Cu, epy) deposited on the silicon wafer. Scale bar is 1 μm. b AFM-measured thicknesses and widths of e-CON(Cu, epy). c Representative AFM image of e-CON(Cu, epy). d Cross-section of the image along the blue line in (c)

Exfoliation by incorporation of pyridine into the porphyrin centers

In order to exfoliate DhaTph into 2D polymer layers, we conceived the idea of simultaneously incorporating metal ions and pyridine (3.8 Å in perpendicular to the porphyrin plane) ligands into the porphyrin center to disrupt π-π stacking between the DhaTph layers (π-π distance (∼4 Å)).

Initially, we chose to simultaneously incorporate magnesium (Mg) or copper (Cu) ions, and axial py ligands into DhaTph. We refer to the exfoliated covalent organic nanodisks (e-CONs) synthesized from DhaTph through the incorporation of Mg or Cu ion, and py axial ligand as “e-CON(Mg, py)” and “e-CON(Cu, py)”, respectively. In a typical procedure, the above-mentioned DhaTph was refluxed in the pyridine containing a variety of divalent metal salts (Supplementary Fig. 1b, c). After reaction for typically 20 h, the e-COFs were collected by filtration and dried for subsequent characterization. Detailed synthetic protocols and product yields are provided in Supplementary Table 2.

To investigate whether or not exfoliation occurs through the simultaneous coordination of the metal and the axial py ligand, as described above, we first measured the PXRD spectrum of each sample in order to confirm loss of crystallinity upon exfoliation. The PXRD peak at 2θ = 3.5°, which corresponds to the (100) plane of the DhaTph, was completely absent in the exfoliated samples, consistent with the dramatic loss of DhaTph crystallinity with the incorporation of either metal ions, as shown in Fig. 1b and Supplementary Fig. 5 for e-CON(Cu, py) and e-CON(Mg, py), respectively. As a control experiment, we confirmed that the peak remained for the sample that was refluxed in pyridine without any metal ion for 20 h (Supplementary Fig. 6, Supplementary Fig. 7), suggesting that refluxing in pyridine alone does not cause the dramatic loss of the crystallite structure. This result is further evidence that the incorporation of the metal ion into the porphyrin is a possible factor determining the exfoliation of DhaTph to disorder the crystal structure of DhaTph.

Subsequently, we measured the FTIR spectra of e-CON(Mg, py) and e-CON(Cu, py) in ATR mode to confirm the incorporation of the metal ion and the py ligand in the e-CON. The FTIR spectra reveal that the −C = N stretching band at 1612 cm−1 (DhaTph imines and pyridine ligand) (Supplementary Fig. 2). Furthermore, we observed characteristic metalloporphyrin band at 1000 cm−1 for both e-CON(Mg, py) and e-CON(Cu, py)32. These results strongly suggest that metal ions and axial pyridine ligands have been incorporated into the e-CON. Energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) further reveal the incorporation of the metal into the porphyrin center, as shown in Supplementary Table 3. We note that the EDS results represent qualitative data for the incorporation of metal ion into porphyrin into the e-CON33.

We next examined the morphologies of e-CON powder by SEM, and the results of which are displayed in Supplementary Fig. 8 for e-CON(Cu, py) and for e-CON(Mg, py), respectively. The morphologies of the DhaTph changed dramatically upon exfoliation, revealing individual disk-like structures after exfoliation in pyridine in the presence of metal ions. In order to determine the degree of exfoliation facilitated by the simultaneous coordination of the pyridine ligands and metal ions to the porphyrin centers, we measured their thickness and width distributions by AFM in tapping mode (Supplementary Figs. 9 and 10). Upon exfoliation, the thicknesses were observed substantially decrease, to 2.3 ± 0.8 nm and 3.0 ± 1.3 nm while their widths were size retained at several hundred nanometers, with values of 124.1 ± 43.6 nm and 182.6 ± 39.4 nm, for e-CON(Mg, py) and e-CON(Cu, py) (n = 30), respectively. The thickness and width distribution are summarized in Supplementary Table 1. The degree of exfoliation achieved using copper ion appears five-fold greater in relation to thickness than that for observed using magnesium ion. We ascribe this increased exfoliation is due to the stability the Cu-metalloporphyrin34. This outcome further supports the hypothesis that the exfoliation of the DhaTph crystals occurs through the simultaneous coordination of the metal center and the pyridine.

The effect of axial ligand size on DhaTph exfoliation

To further optimize the exfoliation method described above for the preparation of sub-nanometer-thickness 2D polymers, 4-methylpyridine (mpy, 4.7 Å) and 4-ethylpyridine (epy, 6.0 Å) were employed as the axial ligands We refer to the resulting e-CONs as “e-CON(M, mpy)” or “e-CON(M, epy)” (M = Cu or Mg).

The PXRD spectra of these e-CON display dramatic decreases in the PXRD peak at 2θ = 3.5°, after 20 h of exfoliation, consistent with the loss of crystallinity, as displayed in Fig. 1 and Supplementary Fig. 5 for Cu and Mg ions, respectively. Time-dependent exfoliation experiments using epy reveal that crystallinity is significantly lost within 2 h (Supplementary Figs. 11 and 12 for Mg and Cu, respectively). This distinctive loss of crystallinity through heating at 120 °C in mpy and epy for 20 h was not observed by PXRD in the absence of the metal (Supplementary Fig. 6), confirming that the simultaneous incorporation of both the ligand and the metal are important for DhaTph exfoliation.

The FTIR spectra of e-CON(M, mpy) and e-CON(M, epy) formed after 20 h, are displayed in Supplementary Fig. 13 for mpy, and Supplementary Figs. 14 and 15 for epy, respectively. The FTIR spectra of mpy and epy used in this study (20 h) are also displayed for comparison. We observed the C = N stretching band at 1612 cm−1 and the metalloporphyrin band at 1000 cm−1 in each case32. To further confirm the incorporation of the ligands and the metals into the porphyrin centers, we conducted time-dependent experiments using the epy ligand (Supplementary Figs. 14 and 15 for Cu and Mg, respectively). The metal (1000 cm−1)32 and ligand (1612 cm−1) incorporation ratio increased with increasing reaction time. These results clearly indicate that the metal ion and ligand were incorporated into the porphyrin center of the DhaTph during the exfoliation reactions.

Supplementary Table 3 summarizes the results of EDS experiments performed on e-CON(Mg, epy) and e-CON(Cu, epy) formed after 20 h of the reaction. In order to quantify the ratio of metals in these COFs, we examined COFs and e-CON(Cu, epy) by inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectroscopy (ICP-AES) measurements (Supplementary Table 4). We observed 4.3 weight % Cu content, indicating that most of the porphyrin units (approximately 90%) in e-CON(Cu, epy) contain Cu in their porphyrin centers. This is also consistent with the increase of the amount of weight after the reaction, assuming that Cu ions consist of one or two pyridines at the site Supplementary Table 2. This suggests that the incorporation of this amount of the metal is sufficient to exfoliate COFs into 2D porphyrin polymers. The FTIR results also reveal that the 1612 cm−1 band increases in intensity as a result of the incorporation of the ligands into the porphyrins, although quantification is difficult due to the overlap with the Shiff-base band around 1612 cm−1.

SEM images of the powder also reveal disk-like shapes after exfoliation using mpy or epy (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Fig. 8). In order to examine their structures further, we also measured the thickness and width distributions of these e-CONs by AFM in tapping mode, and representative AFM images and their results are shown in Fig. 2, Supplementary Figs. 16–18 for e-CON(Cu, mpy or epy) and e-CON(Mg, mpy or epy), respectively. Interestingly, nanometer thick, 1.0 ± 0.4 nm (n = 30) 2D porphyrin polymers was observed for e-CON(Cu, epy) after 20 h of the exfoliation (Fig. 2c). These results reveal that the incorporation of copper ions and epy induces exfoliation to produce nanometer-thick e-CON. The exact values of the thickness and width are listed in Supplementary Table 1. Consequently, we successfully synthesized nanometer thick 2D polymers using copper and epy.

For the further characterization of synthesized nanodisk materials, gas isotherm adsorption, elemental analysis and thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) were conducted (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Table 5). After the reaction, we observed the drastic difference on the adsorption of N2 gas, representing that the pore shape was completely disordered after the reaction. In addition, we observed the ash formation after the TGA measurement, representing the incorporation of metals in the nanodisk. To understand the detailed structure of synthesized nanodisk, Grazing Incidence X-ray Diffraction (GIXD) is commonly used method to understand the thin layers of nanodisks. However, the solubility of nanodisk synthesized here is low and difficult to fabricate the film. Then, we measured their HR-TEM images to understand their structure to check the ordered structure in DhaTph, but not in the e-CON(Cu, epy) (Supplementary Fig. 19).

The detailed characterization for e-CON(Cu, epy). a BET results for DhaTph (black) and e-CON(Cu, epy) (red) with black circles for adsorption and white triangles for desorption, respectively. b TGA of DhaTph (black) and e-CON(Cu, epy) (red), respectively. c, d XPS data for the N1s for DhaTph (c) and e-CON(Cu, epy) (d), respectively. The binding energy for the fitting in the colored lines are shown

The incorporation of Cu in e-CON(Cu, epy) was further confirmed by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS, Fig. 3b, c and Supplementary Figs. 20 and 21). The N1s spectra clearly indicated the incorporation of Cu ion in the nanodisk35,36,37,38. We further observed a peak with a the binding energy of 935 eV, attributable to the Cu2p3/22+ oxidation state, characteristic of copper metalloporphyrin39 and is further evidence in support of the formation of the metalloporphyrin unit in these ultrathin 2D COFs (Supplementary Fig. 21). The exfoliation was carried out with a huge excess of pyridines as axial ligands. The quantification of axial ligand was difficult using FTIR measurement, but the linker signal of (−C = N−) overlapping hinder the quantification of pyridines on the nanodisks. Furthermore, the removal of pyridines from nanodisks to produce the pristine materials would be addressed in the future study, although we cannot prevent the decreased size of the products.

Photochemical properties and hydrogen evolution

In order to examine the photochemical properties of DhaTph and the e-CON, we first acquired diffuse reflectance spectra of their powders40 sandwiched between glass coverslips using an integrating sphere attachment (360–1500 nm range, Supplementary Fig. 22). The absorption spectra of the monomeric porphyrins (1, Mg-Tph (3), and Cu-Tph (4)) in toluene solutions are also shown in Supplementary Fig. 23, which depict typical Soret bands (S0 to S2 transition) at 430 nm and Q-bands (S0 to S1) at 500–700 nm. Diffuse reflectance spectra obtained from powder samples of 1, DhaTph and e-CON(Cu, epy), which not only broadened Soret band, but also broadened Q-bands in the NIR region. Similar observations were reported by Dichtel et al. for phthalocyanine COFs40. We used the NIR excitation wavelength in photocatalytic H2 evolution experiments discussed below. Photoluminescence spectra of monomers in toluene are displayed in Supplementary Fig. 23d. The emission maxima at 663 nm from Q-band were observed for these solution samples. Photoluminescence spectra of the solid samples on glass coverslips were acquired at an excitation wavelength of 408 nm in Supplementary Fig. 24. Dramatic decreases in fluorescence intensity were observed for the DhaTph and e-CON. Photo-electrochemical measurements of e-CON(Cu, epy) were performed using visible or NIR light (Fig. 4a). A three-electrode system with Ag/AgCl-reference and Pt-counter electrodes was used to measure the photocurrent. e-CON(Cu, epy) with 0.2% Nafion was dropped onto carbon electrodes to prepare film-coated working electrodes. Photocurrent responses were recorded over repeated on-off irradiation cycles (30 s, each) under ambient conditions (Fig. 4b). Photoirradiated wavelength-dependence on the Nyquist plots is shown in Supplementary Fig. 25. Photocurrent responses were observed during irradiation with visible light (>420 nm) as well as NIR light (>780 nm) to be consistent with the broad spectral absorption.

Photocatalytic activities of the exfoliated DhaTph. a Photocurrents upon irradiation of e-CON(Cu, epy) with visible (>420 nm) and NIR (>780 nm) light. Red and green colored periods indicated irradiation periods. b H2 evolution upon irradiation with visible (>420 nm) and NIR (>780 nm) light using e-CON(Cu, epy)/Pt/RGO (red) and DhaTph /Pt/RGO (black), 1.0 sun light from a solar simulator long-passed at 420 nm or 780 nm was used in these experiments

Porphyrin has been employed as a photosentsitizer for the photochemical generation of H220. Previously, visible-light sources have been used for photocatalytic reactions, such as the H2 evolution reaction, with composite materials composed of Pt nanoparticles/ reduced-graphene oxide (RGO)41. TEM images of these complexes are displayed in Supplementary Fig. 26. Here, we evaluated photocatalytic activities driven by visible (>420 nm) as well as NIR light (>780 nm). We investigated the H2 evolution reaction of dispersed polymer solutions upon photoirradiation. The enhanced H2 evolution was observed for e-CON(Cu, epy)/Pt/RGO, compared with DhaTph/Pt/RGO (Fig. 4b). The apparent quantum yields for H2 evolution for e-CON(Cu, epy)/Pt/RGO were 5.1% (at 420 nm) and 2.3% (at 780 nm), respectively. This enhancement in the activity might be arise from the higher surface area between e-CON and Pt/RGO, although the further detailed studies are necessarily to understand the detailed mechanisms on the enhancement42. Band gaps were determined from Tauc plots and are listed in Supplementary Table 6. Valence-band levels were determined by photoelectron-yield spectroscopy (PYS), and the valence-band level of e-CON(Cu, epy) was found to be 0.5 V vs NHE. In the case of Pt/RGO, distinctive H2 evolution was not observed (Supplementary Fig. 27). Moreover, the photocatalytic stability of e-CON(Cu, epy) for H2 evolution reaction was examined by cycle experiments. Supplementary Fig. 28 displays continuous H2 evolution without noticeable degradation in the subsequent runs, indicating that the as-prepared e-CON(Cu, epy) can be acted as a stable photocatalyst for H2-evolution reaction.

Discussion

We successfully synthesized a nanometer-thick 2D porphyrin polymer, by exfoliating COFs composed of porphyrin units, through the coordination of axial ligands. We confirmed that the simultaneous addition of metal ions and ligands induced the exfoliation of DhaTph to produce nanometer-thick 2D porphyrin polymer, when Cu ion and epy were used. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to report the exfoliation of DhaTph through the incorporation of axial ligand for the synthesis of nanometer exfoliated 2D porphyrin polymers. Furthermore, we discovered that these exfoliated DhaTph photo-catalyze the H2 evolution reaction upon irradiation with visible (>420 nm) and NIR (>780 nm) light. We demonstrated a way of engineering 2D polymers and showed that these polymers are photo-functional materials for use in photocatalytic reactions.

Methods

General information

Toluene, pyridine, and 4-methylpyridine were purchased from Wako (Osaka, Japan). Acetic acid and ethanol were purchased from Nacalai Tesque (Kyoto, Japan). 5,10,15,20-Tetrakis(4-aminophenyl)-21H,23H-porphyrin) was purchased from TCI (Tokyo, Japan). The other reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Tokyo, Japan). All reagents were used as received without further purification.

Spectroscopy

1H NMR spectra were recorded in CDCl3 on a JEOL ECS-400 NMR spectrometer (Tokyo, Japan). Powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) spectra were acquired on a RIGAKU Smart lab (Tokyo, Japan) diffractometer equipped with a target Cu-Kα (α = 1.5418 Å) source opening at a voltage of 45 kV, a current of 200 mA, and a scanning speed 5 °/min. The crystalline inter-planar distance (d) was determined using Bragg’s equation: nα = 2dsinθ. Fourier-Transform infrared spectra (FTIR) were acquired on a JASCO (Tokyo, Japan) FTIR 4100 spectrometer in attenuated total reflection mode over 600–4000 cm−1 spectral range with 16 cumulative scans. Solid state absorption spectra were measured on a Shimadzu (Kyoto, Japan) UV3600 absorption spectrometer equipped with an ISR-240A integrating sphere. The sample was placed between coverslip (24 × 32 mm2, #1, Neo cover glass, Matsunami) and attached to the BaSO4 plate. The grating was changed at 720 nm and the slit size was 5 nm. The solution state UV-vis absorption spectrum was measured on a V-630 bio absorption spectrometer (JASCO, Tokyo, Japan) using 1 × 1 cm2 cuvette. The sample concentration was approximately adjusted to absorption = 0.1 at 420 nm for the following solution phase fluorescence measurements. The solution state fluorescence absorption spectrum was measured on a FP-8200 fluorescence spectrometer (JASCO, Tokyo, Japan) using 1 × 0.5 cm2 cuvette. The sample concentration was approximately adjusted to the absorption of 0.1 at 420 nm for the following solution phase fluorescence measurements. Scan speed was 200 nm/min and excitation wavelength was 420 nm and measured the spectra from 650–750 nm. ICP-AES measurement was performed at the Toray Research Center, Inc. (Shiga, Japan) or using an ICPS-8100 (SIMADZU, Kyoto, Japan). XPS measurement was done by a JPS-9100 (JEOL, Tokyo, Japan). Sample was dropped on the carbon tape for the measurement.

Microscopy

Atomic force microscopy (AFM) was performed using a Seiko Instruments (Chiba, Japan) SPI3800/SPA400 AFM in tapping mode under ambient conditions. Each sample was dispersed in dimethylformamide (DMF) or ethanol and sonicated for 1 min (SHARP UT-206). The dispersed solution was then spin coated onto freshly prepared mica (1 × 1 cm). Trace was constructed by Gwyddion software. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images were acquired on a JEOL (Tokyo, Japan) JSM-6330F at an accelerator voltage of 20.0 kV, an emission current of 12 μA, and a working distance of 8.0 nm. Each sample of powder was placed onto carbon tape or dispersed solution on silicon wafer for SEM analysis. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) was performed at an accelerator potential of 200 kV using a JEOL JEM-2100, JEOL. Each sample was deposited onto a Cu grid for the acquisition of the TEM images.

Photo-electrochemistry

Photo-electrochemical experiments were carried out using an ALS CH1660B, BAS (Tokyo, Japan) using a three-electrode system. The electrolyte was NaSO4 (0.1 M), and Ag/AgCl-reference and platinum-counter electrodes were used for the measurements. The working electrode was a DhaTph or an e-CON(Cu, epy) film coated on a carbon electrode. Films were prepared by quickly dispersing the a DhaTph or an e-CON(Cu, epy) (1 mg) in ethanol (100 μL) and water (60 μL). Aqueous Nafion (5%, 4 μL) was mixed into the above solution (20 μL), and an aliquot (3 μL) of the resultant solution was deposited onto the carbon electrode, followed by drying at room temperature for further measurement. Photoirradiation was performed using a HAL-320W solar simulator (Asahi spectra, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with 420 nm (for visible light) or 780 nm (for NIR light) long-pass filters. The irradiation power was ca. 3 × 102 mW cm−2 at wavelengths greater than for >420 nm and >780 nm, respectively. For the H2 evolution reaction experiments, the DhaTph or e-CON(Cu, epy) was dissolved in water at a concentration of 0.5 mg/mL and sonicated for 10 min. An aliquot of this solution (0.5 mL) and Pt/RGO (0.25 mL) were transferred to a 30 mL test tube, and water (4.05 mL) and EDTA (0.2 mL, 0.5 M) were added. The test tube was sealed with a W-18 rubber cap (Sansho, Osaka, Japan), followed by bubbling with argon gas for 30 min prior to photoirradiation with 1.0 sun light, long-passed with 420 nm for visible or 780 nm filter for NIR light. The amount of H2 was detected by a gas chromatography using a TCD detector (GC-8A, Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan). The column temperature was 100 °C, the detector current was 60 mA, the primary pressure was 600 kPa and the carrier gas pressure was 300 kPa. A calibration curve was constructed using H2-standard gas (1020–11201, GL science) in order to determine the amount of H2. Photoelectron yield spectroscopy (PYS) was performed on a Bunkoukeiki (Tokyo, Japan) BIP-KV202GD spectrometer.

Synthesis of 2,5-dihydroxyterephthalaldehyde (Dha, 2)

Dihydroxyterephthalaldehyde (Dha) was synthesized following the procedure reported by Wagner43. In brief, 2,5-dimethoxybenzene-1,4-dicarboxaldehyde (Dma, 370 mg, 1.9 mmol), acetic acid (19 mL), and aqueous hydrogen bromide (47%, 16 mL) was added to a 100 mL flask and refluxed for 20 h. After cooling, water (7.5 mL) was added to the solution, followed by extraction with chloroform (3 × 7.5 mL). The organic layer was dried over Na2SO4, filtrated, and concentrated by rotary evaporation. Toluene (30 mL) was added to aid in the co-evaporation of the acetic acid, followed by concentration by rotary evaporation to afford 2 (120 mg 42%). 1H-NMR (CDCl3): δ 10.2 (s, 2H, OH), 12.8 (2, 2H, CHO), 7.2 (s, 2H, aromatic).

General procedure for the synthesis of the DhaTph

DhaTph was synthesized following the procedure reported by Banerjee30. In a typical experiment, 5,10,15,20-tetrakis(4-aminophenyl)-21H,23H-porphyrin) (28 mg) and 2 (14 mg) in a 5:5:1 mixture of ethanol:dichlorobenzene:acetic acid (6N) was added to a 50 mL round-bottomed flask, and the mixture was refluxed at 120 °C for 3 d. After cooling, the mixture was filtrated using #3 ϕ 40 mm Kiriyama filter paper (Kiriyama, Tokyo, Japan) and washed several times with ethanol. The resulting solid was dried under vacuum to afford the DhaTph (39 mg, 93%).

General procedure for the synthesis of e-CONs

The DhaTph and the metal salt were added to a 50-mL-round-bottomed flask and the ligand (10–15 mL) was added as solvent. The resulting mixture was typically refluxed at 120 °C for 20 h. In the time-dependent experiments, the reaction times were adjusted as indicated in the text. The reaction mixture was filtered, and the solid was washed with water, and dried under vacuum to afford the e-CONs. Typical synthetic reagents and results are summarized in Supplementary Table 2.

Data availability

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its supplementary information files.

References

Xia, F., Wang, H., Xiao, D., Dubey, M. & Ramasubramaniam, A. Two-dimensional material nanophotonics. Nat. Photonics 8, 899–907 (2014).

Rodriguez-San-Miguel, D., Amo-Ochoa, P. & Zamora, F. MasterChem: cooking 2D-polymers. Chem. Commun. 52, 4113–4127 (2016).

Kissel, P., Murray, D. J., Wulftange, W. J., Catalano, V. J. & King, B. T. A nanoporous two-dimensional polymer by single-crystal-to-single-crystal photopolymerization. Nat. Chem. 6, 774–778 (2014).

Kory, M. J. et al. Gram-scale synthesis of two-dimensional polymer crystals and their structure analysis by X-ray diffraction. Nat. Chem. 6, 779–784 (2014).

Liu, X.-H., Guan, C.-Z., Wang, D. & Wan, L.-J. Graphene-like single-layered covalent organic frameworks: synthesis strategies and application prospects. Adv. Mater. 26, 6912–6920 (2014).

Hernandez, Y. et al. High-yield production of graphene by liquid-phase exfoliation of graphite. Nat. Nanotechnol. 3, 563–568 (2008).

Wojcik, A. & Kamat, P. V. Reduced graphene oxide and porphyrin. Interact. Aff. 2-D. ACS Nano 4, 6697–6706 (2010).

Coleman, J. N. et al. Two-dimensional nanosheets produced by liquid exfoliation of layered materials. Science 331, 568–571 (2011).

Feng, X., Ding, X. & Jiang, D. Covalent organic frameworks. Chem. Soc. Rev. 41, 6010–6022 (2012).

Xu, H. & Jiang, D. Covalent organic frameworks Crossing the channel. Nat. Chem. 6, 564–566 (2014).

Waller, P. J., Gandara, F. & Yaghi, O. M. Chemistry of covalent organic frameworks. Acc. Chem. Res. 48, 3053–3063 (2015).

Khayum, M. A. et al. Chemically Delaminated Free-Standing Ultrathin Covalent Organic Nanosheets. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 55, 15604–15608 (2016).

Kandambeth, S. et al. Selective molecular sieving in self-standing porous covalent-organic-framework membranes. Adv. Mater. 29, 1603945 (2017).

Berlanga, I. et al. Delamination of layered covalent organic frameworks. Small 7, 1207–1211 (2011).

Berlanga, I., Mas-Balleste, R. & Zamora, F. Tuning delamination of layered covalent organic frameworks through structural design. Chem. Commun. 48, 7976–7978 (2012).

Bunck, D. N. & Dichtel, W. R. Bulk synthesis of exfoliated two-dimensional polymers using hydrazone-linked covalent organic frameworks. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 14952–14955 (2013).

Wang, S. et al. Exfoliation of covalent organic frameworks into few-layer redox-active nanosheets as cathode materials for lithium-ion batteries. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 4258–4261 (2017).

Mitra, S. et al. Self-exfoliated guanidinium-based ionic covalent organic nanosheets (iCONs). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 2823–2828 (2016).

Colson, J. W. & Dichtel, W. R. Rationally synthesized two-dimensional polymers. Nat. Chem. 5, 453–465 (2013).

Ladomenou, K. et al. Photochemical hydrogen generation with porphyrin-based systems. Coord. Chem. Rev. 304-305, 38–54 (2015).

Lin, S. et al. Covalent organic frameworks comprising cobalt porphyrins for catalytic CO2 reduction in water. Science 349, 1208–1213 (2015).

Mukherjee, G. et al. A porous porphyrin organic polymer (PPOP) for visible light triggered hydrogen production. Chem. Commun. 53, 4461–4464 (2017).

Vyas, V. S. et al. A tunable azine covalent organic framework platform for visible light-induced hydrogen generation. Nat. Commun. 6, 8508 (2015).

Xu, H.-Q. et al. Visible-light photoreduction of CO2 in a metal-organic framework: Boosting electron-hole separation via electron trap states. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 13440–13443 (2015).

Fateeva, A. et al. A water-stable porphyrin-based metal-organic framework active for visible-light photocatalysis. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 51, 7440–7444 (2012).

Stegbauer, L., Schwinghammer, K. & Lotsch, B. V. A hydrazone-based covalent organic framework for photocatalytic hydrogen production. Chem. Sci. 5, 2789–2793 (2014).

Li, L. et al. Sulfur-doped covalent triazine-based frameworks for enhanced photocatalytic hydrogen evolution from water under visible light. J. Mater. Chem. A 4, 12402–12406 (2016).

Pachfule, P. et al. Diacetylene functionalized covalent organic framework (COF) for photocatalytic hydrogen generation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 1423–1427 (2018).

Banerjee, T., Gottschling, K., Savasci, G., Ochsenfeld, C. & Lotsch, B. V. H2 evolution with covalent organic framework photocatalysts. ACS Energy Lett. 3, 400–409 (2018).

Kandambeth, S. et al. Enhancement of chemical stability and crystallinity in porphyrin-containing covalent organic frameworks by intramolecular hydrogen bonds. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 52, 13052–13056 (2013).

Chen, X. et al. Locking covalent organic frameworks with hydrogen bonds: General and remarkable effects on crystalline structure, physical properties, and photochemical activity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 3241–3247 (2015).

Nadeem, S., Abdul Mutalib, M. I. & Shaharun, M. S. One pot syntheses and characterization of meso- 5, 10, 15, 20-copper tetraphenylporphyrin. Rasayan J. Chem. 9, 309–314 (2016).

Newbury, D. E. & Ritchie, N. W. M. Is scanning electron microscopy/energy dispersive x-ray spectrometry (SEM/EDS) quantitative? Scanning 35, 141–168 (2013).

Domingues, M. R. M., Santana-Marques, M. G. & Ferrer-Correia, A. J. Formation of metalloporphyrins and metallochlorins in the source of a mass spectrometer under fast atom bombardment. Int. J. Mass Spectrom. Ion-. Process. 165/166, 551–559 (1997).

Eskelsen, J. R. et al. Correlating elastic properties and molecular organization of an ionic organic nanostructure. Nanoscale 6, 316–327 (2014).

Zhu, K. et al. The study of a novel cobalt-implanted pyridylporphyrin/graphene oxide nanohybrid for enhanced photocatalytic hydrogen evolution and its electron transfer mechanism. Nanoscale 10, 18635–18641 (2018).

Huang, G. et al. Effect of mesoporous chitosan action and coordination on the catalytic activity of mesoporous chitosan-grafted cobalt tetrakis(p-sulfophenyl) porphyrin for ethylbenzene oxidation. Catalysts 8, 199/191–199/116 (2018).

Liu, Y. et al. Chemical adsorption enhanced CO2 capture and photoreduction over a copper porphyrin based metal organic framework. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 5, 7654–7658 (2013).

Reid, I. et al. Electronic structure of the organic semiconductor copper tetraphenylporphyrin (CuTPP). Appl. Surf. Sci. 256, 720–725 (2009).

Spitler, E. L. & Dichtel, W. R. Lewis acid-catalysed formation of two-dimensional phthalocyanine covalent organic frameworks. Nat. Chem. 2, 672–677 (2010).

Zhu, M. et al. Surfactant assistance in improvement of photocatalytic hydrogen production with the porphyrin noncovalently functionalized graphene nanocomposite. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 5, 1732–1740 (2013).

Liu, G. et al. Nature-inspired environmental “Phosphorylation” boosts photocatalytic H2 production over carbon nitride nanosheets under visible-light irradiation. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 54, 13561–13565 (2015).

Kretz, T. B., Willem, Lerner, Hans-Wolfram & Wagner, Matthias 2,5-Diformylbenzene-1,4-diol: a versatile building block for the synthesis of ditopic redox-active Schiff base ligands. Z. Naturforsch. B 62, 66–74 (2007).

Acknowledgements

We thank the members of Comprehensive Analytical Center at SANKEN for their generous support. We also thank the Nanotechnology Open Facility at SANKEN for PYS measurements. This work was partly supported by the Cooperative Research Program of “Network Joint Research Center for Materials and Devices”, Osaka University, and Innovative Project for Advanced Instruments, Renovation Center of Instruments for Science Education and Technology, Osaka University, and Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (Projects JP15K13672 (Y.O.) and others) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) of the Japanese government, the Initiative for realizing diversity in the research environment project and startup for Institute for Advanced Co-Creation Studies at Osaka University, the Murata Science Foundation, and the Kato Foundation for Promotion of Science (Y.O.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.O. conceived the research and supervised the entire project. K.N. conducted most of the initial COFs and e-CONs synthesis and their structural characterization. Z.F. conducted synthesis, AFM measurement and XPS measurement. M.Z. conducted the electrochemical experiments and the H2 evolution experiments. X. L. helped the synthesis of COFs and e-CONs. J.X contributed to the XPS measurements. T.M. supervised the project. Y.O. wrote the original manuscript and all authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fan, Z., Nomura, K., Zhu, M. et al. Synthesis and photocatalytic activity of ultrathin two-dimensional porphyrin nanodisks via covalent organic framework exfoliation. Commun Chem 2, 55 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-019-0158-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-019-0158-8

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.