Abstract

Aggressive behavior in our modern, civilized society is often counterproductive and destructive. Identifying specific proteins involved in the disease can serve as therapeutic targets for treating aggression. Here, we found that overexpression of RGS2 in explicitly serotonergic neurons augments male aggression in control mice and rescues male aggression in Rgs2−/− mice, while anxiety is not affected. The aggressive behavior is directly correlated to the immediate early gene c-fos induction in the dorsal raphe nuclei and ventrolateral part of the ventromedial nucleus hypothalamus, to an increase in spontaneous firing in serotonergic neurons and to a reduction in the modulatory action of Gi/o and Gq/11 coupled 5HT and adrenergic receptors in serotonergic neurons of Rgs2-expressing mice. Collectively, these findings specifically identify that RGS2 expression in serotonergic neurons is sufficient to drive male aggression in mice and as a potential therapeutic target for treating aggression.

Similar content being viewed by others

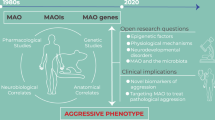

Introduction

Regulators of G protein signaling (RGS) proteins terminate G protein signals by accelerating the intrinsic GTPase activity of the G protein. In addition, RGS proteins can act as effector antagonists by blocking, for example, Gi/o, Gq/11, and Gs pathways1,2. The RGS family comprises more than 20 different family members identified in mammalian tissues where RGS2 belongs to the subgroup of small RGS proteins. This subgroup is characterized by small N- and C-termini flanking a conserved 130 amino acid long intra-protein domain also known as RGS domain, which is responsible for their interaction and activity on the G protein α-subunit3.

RGS2 is expressed in the periphery and brain and has been identified as an immediate early gene (IEG). Rapid upregulation of RGS2 expression has been shown, for example, in various brain regions like the hippocampus by excitatory stimuli4. These results suggest a regulatory role of RGS2 in synaptic transmission and synaptic plasticity during behavior. Indeed, RGS2 increases synaptic vesicle release at the presynaptic terminals via downregulation of Gi/o-mediated Ca2+ channel inhibition and Rgs2−/− mice reveal a decrease in synaptic transmission, but increase in long-term potentiation in the hippocampus5. The changes in synaptic plasticity may contribute to the increased anxiety and reduced male aggression of the Rgs2−/− mice5,6,7.

RGS2 has been identified as a quantitative trait for anxiety and variations within the Rgs2 gene are expected to play a role for the development of anxiety in humans8,9. Human genetic association studies linking RGS2 polymorphisms to panic disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, social anxiety disorder, and post-traumatic stress disorder10,11,12,13,14,15,16. Past meta-analytical integration studies examining the anxiety disorders in twins showed a genetic heritability of 31.6%. Generalized anxiety disorders (GADs) are responsible for 23% genetic variance, with the rest being accountable by unusual environmental factors. Several genetic studies implicate GAD susceptibility genes in the serotonergic and catecholaminergic systems, which are in part modulated by RGS2 (i.e. 5HTT, 5HT1A, MAOA) and the BDNF gene. Additionally, polymorphisms in the neuropeptide S receptor (NPSR1), neuropeptide Y receptor (NPYR), and corticotropin-releasing hormone receptor (CRHR1) genes with individuals exposed to catastrophic events such as a hurricane or early trauma are more susceptible to GAD and anxiety sensitivity. More importantly, RGS2 demonstrated a dose–response correlation to post hurricane GAD in mostly female victims17,18. Polymorphisms in specific genes appear to predispose individuals to GAD and anxiety sensitivity under stressful or traumatic environmental conditions.

Anxiety disorder and phenotypes are often associated with altered aggression, suggesting that overlapping and interconnected neuronal circuits are involved in the modulation of both behaviors19,20. Mouse models knocking out Rgs2 (Rgs2−/−) show increased anxiety and decreased male aggression7,21. Furthermore, mice treated with oxytocin demonstrated decreased anxiety with increased RGS2 expression22. Numerous reports in humans also implicate serotonin (5HT) involvement in regulating impulsive aggression. Functional polymorphisms in humans to the 5HT receptors and 5HT transporter (5HTT) were found to be associated with impulsive aggressive behaviors23. In addition, humans with polymorphisms in enzymes, which influence the production, release, and degradation of 5HT, are genetically predisposed to aggression. Polymorphisms identified in another enzyme, tryptophan hydroxylase (TPH) that catalyzes the rate-limiting step in 5HT synthesis, has been associated with susceptibility to borderline personality disorder, aggression, impulsivity, and suicidal behavior23. Together, these data suggest that 5HT may be the common neurotransmitter modulating and interconnecting the neuronal circuits underlying anxiety and aggression19,24. This is, for example, suggested by the fact that when the majority of serotonergic neurons lose their 5HT identity in the brain, it leads to increased aggression and anxiety in mice25. In general, changes in 5HT levels in the brain have been associated with altered anxiety and aggression. However, how changes in 5HT activity and 5HT release during behavior relate to an increase or decrease in anxiety and aggression is still controversial and may depend on the behavioral context and genetic background of the animal. In addition, whether RGS proteins such as RGS2 modulate anxiety and aggression via modulating the activity of 5HT neurons have not been explored.

Rgs2 mRNA has been detected in the dorsal raphe nuclei (DRN), one of the brain nuclei where serotonergic neurons originate26. Various Gi/o- and Gq-coupled GPCRs (G protein-coupled receptors), including 5HT1A and 5HT1B and α1 adrenergic (α1AR) receptors, have been identified in the serotonergic system and recent studies performed in heterologous expression systems showed that these receptor pathways are modulated by RGS proteins including RGS2 (refs27,28). Furthermore, RGS2 expression levels seem to correlate with 5HT1A and 5HT1B receptor expression levels in the DRN21. To investigate whether RGS2 regulates anxious and aggressive behavior via the serotonergic system in mice, we generated mice overexpressing Rgs2 specifically in serotonergic neurons. Exogenous expression of Rgs2 only in serotonergic neurons of the DRN augmented aggressive but not anxious behavior in mice. In addition, Rgs2-overexpressing mice were able to rescue the aggressive but not anxious phenotype in Rgs2−/− mice. Interestingly, exogenous expression of Rgs2 specifically in serotonergic neurons leads to increases in serotonergic firing, reduction/block of 5HT1B and α1AR modulation, and increased c-fos expression in the DRN and ventrolateral area of the ventromedial nucleus hypothalamus (VMHvl) after aggressive behavior.

Results

Detection of Rgs2 mRNA in serotonergic neurons

Since the serotonergic system and RGS2 was previously found to be involved in anxiety and aggression in mice7,25, we wanted to investigate whether RGS2 is modulating anxiety and aggression through the serotonergic system. Since there is no specific antibody available for RGS2 to determine if Rgs2 was expressed in serotonergic neurons, we used fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) of YFP-expressing serotonergic neurons5,29,30, followed by an Affymetrix gene array to detect differences in Rgs2 and the closely related RGS family member Rgs4 mRNA levels in serotonergic (5HT) neurons. RGS4 has also been described to modulate synaptic plasticity and to be expressed in the DRN in non-serotonergic neurons30,31. Dissociated serotonergic neurons from the DRN of E12.5 ePet-YFP+ mice were previously enriched with FACS where serotonergic neurons are expressing YFP (YFP+). Rgs2 mRNA was expressed in serotonergic YFP+ neurons but not Rgs4 (Fig. 1a). We also confirmed the Rgs2 mRNA expression in hippocampal cultures from wild-type mice but not Rgs2−/− mice as a control. 18S RNA was used as an internal control to normalize the relative Rgs2 and Rgs4 mRNA levels (Fig. 1c). To verify the serotonergic specificity of DRN-dissociated neurons, Pet-1 and tryptophan hydroxylase 2 (Tph2) levels were measured in serotonergic YFP+ and YFP− neurons from the DRN. mRNA levels of Pet-1 and Tph2 was evident in YFP+ but not YFP− neurons (Fig. 1b). Low levels of Pet-1 are not surprising since Pet-1 is a transcription factor initially being expressed at around E10.5. These findings demonstrate that Rgs2 is expressed in serotonergic neurons and suggest that Rgs2 has a specific function in the serotonergic transmitter system.

Rgs2 mRNA is detected in YFP-positive, serotonergic neurons by real-time quantitative PCR. a The relative Rgs2 mRNA expression from hippocampal neurons cultured from wild-type (WT; black circles) or Rgs2-knockout (Rgs2−/−, grey diamonds) mice. As expected, WT hippocampal neurons express Rgs2 mRNA but not Rgs2−/− hippocampal neurons. The relative Rgs2 (yellow triangles) or Rgs4 (white triangles) mRNA expression from serotonergic neurons cultured from ePet-YFP+ (YFP+), embryonic day 12.5 (E12.5) mice. mRNA from Rgs2 but not Rgs4 was detected. b The YFP-positive (YFP+) serotonergic neurons but not the YFP-negative neurons (YFP−, white triangles) express the Pet-1 and tryptophan hydroxylase 2 (Tph2) showing that YFP+ (yellow triangles) neurons are serotonergic neurons. β-actin was measured as an internal loading control and expressed at equal levels in the YFP+ and YFP− neurons. The low level of Pet-1 is most likely related to the fact that Pet-1 is a transcription factor initially expressed at E10.5 when the 5HT cells were sorted. c To compare the relative mRNA levels of Rgs2, Rgs4, Tph2, Pet-1, and β-actin from a, b in different neuronal cultures 18S RNA was used as an internal control and normalized to the amount of 18S RNA found in hippocampal or serotonergic neurons from each respective mRNA sample. The experiments were performed with three independent neuronal cultures in duplicates (n = 6). Relative gene expression data was analyzed with 2–ΔΔCT method80 and reported as mean ± SD. Statistical significance was evaluated with ANOVA (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001)

Creation of ePet-Rgs2 transgenic mouse lines

To investigate the physiological function and behavioral consequences of Rgs2 expression in the serotonergic system of mice, we used the Pet-1 enhancer region to overexpress Rgs2 specifically in the serotonergic system. The transcription factor Pet-1 is required for the development of the serotonergic system in the mouse brain30,32,33. A 5′ genomic fragment flanking the mouse Pet-1 gene restricts the expression of the reporter gene β-galactosidase to serotonergic neurons during development and in adult mice, indicating that the gene of interest Rgs2 will also be restricted to serotonergic neurons. Most importantly, the Pet-1 reporter shows highly reproducible 5HT-specific expression among independent transgenic mouse lines29,33. For stable integration of Rgs2 into the mouse genome, the Rgs2-IRES-GFP construct was subcloned 3′ to the β-globin minimal promoter and 40 kb serotonergic-specific ePet-1 enhancer in the modified pBACe3.6 vector (Fig. 2a) to create BAC transgenic mouse lines expressing Rgs2 specifically in serotonergic neurons. We selected two of the nine founder lines, which bred well and revealed a low and high expression of RGS2/GFP specifically in 5HT neurons (lines ePet-Rgs2lo and ePet-Rgs2hi; Fig. 2c). Quantitative analysis of the GFP intensity in 5HT neurons from ePet-Rgs2hi compared to ePet-Rgs2lo mice revealed a 2-fold increase in GFP expression (Fig. 2b). Since no specific antibody is available for RGS2, we analyzed Rgs2 mRNA levels in serotonergic neurons by single-cell reverse transcriptase quantitative PCR (qPCR) from ePet-Rgs2 transgenic mouse lines crossed with ePet-YFP for identification of serotonergic neurons. Rgs2 mRNA levels were 20.6% higher in serotonergic neurons from ePet-Rgs2hi compared to ePet-Rgs2lo mice (Fig. 2d, e).

Creation of transgenic mouse lines overexpressing RGS2 and quantification of Rgs2 mRNA levels specifically in serotonergic neurons. a Schematic of the construct used to create the BAC transgenic mouse lines, ePet-Rgs2lo and ePet-Rgs2hi. Rgs2-IRES-GFP was cloned 3′ of the 40 kb ePet-1 enhancer sequence. b Relative GFP expression levels in serotonergic neurons from ePet-Rgs2lo and ePet-Rgs2hi mouse brains. c Expression of the serotonergic-specific marker Tph, Rgs2-IRES-GFP, and colocalization of Tph and Rgs2-IRES-GFP in the DRN from an ePet-Rgs2lo and ePet-Rgs2hi mouse. d Example gels from single-cell quantitative reverse transcriptase-PCR of Rgs2 and Tph as internal control from YFP+, serotonergic neurons from littermate controllo, ePet-Rgs2lo, littermate controlhi, and ePet-Rgs2hi mouse brains. Serial dilutions from 20 to 24 were prepared from reversely transcribed cDNA. Single-cell qRT-PCRs revealed higher Rgs2 mRNA expression in ePet-Rgs2hi compared to ePet-Rgs2lo mice. e Quantitative analysis of the relative Rgs2 mRNA compared to Tph from serotonergic-positive neurons from control and ePet-Rgs2 transgenic mice indicate a 20.6% increase in Rgs2 mRNA levels in ePet-Rgs2hi compared to ePet-Rgs2lo mice. The number of cells analyzed is reported within parentheses for each mouse line. Relative gene expression data reported as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was evaluated with ANOVA (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001)

Overexpression of RGS2 in serotonergic neurons leads to male aggression

The transgenic mouse lines, ePet-Rgs2lo and ePet-Rgs2hi, exogenously expressing RGS2 in the 5HT system were characterized for male anxiety, depression, and aggressive behaviors in comparison to their wild-type littermates. Both ePet-Rgs2 transgenic mouse lines demonstrated minimal differences in their anxiolytic or depressive behavior compared to their control littermates in the open field, elevated plus maze, place preference, forced swim, or tail suspension tests (Table 1). However, ePet-Rgs2hi male mice exhibited augmented aggressive behavior in the resident intruder and tube dominance tests. ePet-Rgs2hi male mice displayed an increased number and duration of attacks and bites, as well as a shorter latency to their first attack in comparison to their littermate controls and ePet-Rgs2lo male mice in the resident intruder test (Fig. 3a–d, Supplementary Movies 1 and 2). They also demonstrated an increase in number and duration of attacks in the resident intruder test with pups (Fig. 3e, f). Interestingly, the ePet-Rgs2lo male mice indicated a trend for more aggressive behavior in the resident intruder test compared to their littermate controls, which may indicate a RGS2 dosage effect (Fig. 3a–d). Furthermore, the tube dominance test revealed that both ePet-Rgs2 transgenic mouse lines showed robust aggressive behavior compared to control littermates. From 54 trials with randomized opponents, 55% of the ePet-Rgs2lo and 70.4% of the ePet-Rgs2hi male mice forced their control littermates out of the tube (Fig. 3g, h, Supplementary Movie 3). Together, these results suggest that exogenous, serotonergic-specific expression of RGS2 in a dose-dependent manner leads to more aggressive but not anxious behavior in male mice.

Exogenous expression of RGS2 in serotonergic neurons induces aggressive behavior in mice. Exogenous expression of RGS2 in serotonergic neurons in ePet-Rgs2hi mice induce aggressive behavior in the resident intruder test without (a–d) and with pups (e, f) compared to their littermate controls (controllo, grey circles; controlhi, black circles). In the resident intruder test without pups ePet-Rgs2hi (squares) mice but not ePet-Rgs2lo (triangles) showed an increase in the number of attacks (a), an increase in the duration of attacks (b), a decrease in latency to first attack (c), and an increase in the number of bites (d) compared to control and ePet-Rgs2lo mice. The ePet-Rgs2hi mice also displayed an increase number (e) and duration (f) of attacks in the resident intruder test with pups compared to control and ePet-Rgs2lo mice. The number of mice tested is indicated within parentheses. Data are reported as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was evaluated with ANOVA (**p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001). g Aggression in the tube dominance test where mouse pairs are released at opposite ends of a plastic tube. Winners displaced or forced their opponent (loser) out of the tube. Aggression was measured in paired groups of males, littermate controllo (grey) vs. ePet-Rgs2lo (magenta) (g) and littermate controlhi (black) vs. ePet-Rgs2hi (dark blue) (h). Results are indicated as the percentage of displacement per group (winners). Aggressive behavior was pronounced in transgenic mice overexpressing RGS2 in serotonergic neurons. Six trials/mouse were performed with random opponents. The number of mice tested/group is indicated within parentheses

Rescue of RGS2 in 5HT neurons recovers male aggression in Rgs2 −/− mice

RGS2 deficiency in mice leads to an increase in anxiety and decline in male aggression7. To determine if the serotonergic system is involved in RGS2-dependent male aggression, we rescued RGS2 expression specifically in serotonergic neurons of Rgs2−/− mice by crossing them with the ePet-Rgs2 transgenic mouse lines. Both rescue lines showed increased number and duration of attacks in the resident intruder test compared to Rgs2−/− mice (Fig. 4a–d, Supplementary Movies 4 and 5). Moreover, Rgs2 rescue lines demonstrated a decrease in latency to first attack compared to Rgs2−/− mice (Fig. 4e). Surprisingly, Rgs2−/−/ePet-Rgs2lo rescue mice showed an increase in the number of bites, which was not seen in the Rgs2−/−/ePet-Rgs2hi mice (Fig. 4f). Additionally, both rescue lines, Rgs2−/−/ePet-Rgs2lo (78%) and Rgs2−/−/ePet-Rgs2hi (69%), won the majority of their battles in the tube dominance test against their Rgs2−/− littermate controls (Fig. 5a–b, Supplementary Movie 6). Surprisingly, the rescue mice from line Rgs2−/−/ePet-Rgs2lo won 43% of their battles against their exogenous expression ePet-Rgs2lo littermates, and Rgs2−/−/ePet-Rgs2hi mice won 60% of their battles against their exogenous expression ePet-Rgs2hi siblings in the tube dominance test (Fig. 5c, d, Supplementary Movie 7). Similar to the Rgs2 exogenous expression lines, no changes in anxiolytic or depressive behavior was observed in the rescue lines compared to Rgs2−/−mice (Table 2). Together, these results show that rescue of RGS2 in only serotonergic neurons of Rgs2−/− mice is sufficient to recover male aggression but not anxiety, indicating that RGS2 plays a major role in driving male aggression via the serotonergic system.

Rescue of RGS2 in serotonergic neurons recovers aggression in resident intruder test. Increased number and duration of attacks over a 10 min testing period from Rgs2-rescued mice, Rgs2−/−/ePet-Rgs2lo (b) and Rgs2−/−/ePet-Rgs2hi (c) compared to Rgs2−/− mice (a) on resident intruder day 10. The number of mice tested/group is indicated within parentheses. The average duration of attacks (d), latency to first attack (e), and number of bites (f) from Rgs2−/− mice (diamonds) compared to control (circles), Rgs2-rescued, Rgs2−/−/ePet-Rgs2lo (triangles), and Rgs2−/−/ePet-Rgs2hi (squares) mice are depicted as bar graphs. Rgs2-rescued mice showed augmented number and duration of attacks and reduced latency to first attack compared to their Rgs2−/− littermates. As expected, control mice demonstrated increased duration of attacks and reduced latency to first attack compared to their Rgs2−/− littermates. The number of mice tested/group is indicated within parentheses. Data are reported as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was evaluated with ANOVA (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01)

Rescue of RGS2 in serotonergic neurons recovers aggression in Rgs2−/− mice by the tube dominance test. Aggression was measured in combinations of paired groups from knockout (Rgs2−/−), exogenous expression (ePet-Rgs2lo, ePet-Rgs2hi) and rescue lines (Rgs2−/−/ePet-Rgs2lo, Rgs2−/−/ePet-Rgs2hi). Mouse pairs were released at opposite ends of a plastic tube and the winners displaced or forced their opponent out of the tube. Paired groups of males included Rgs2−/− (grey) vs. Rgs2−/−/ePet-Rgs2lo (light magenta) (a), Rgs2−/− (grey) vs. ePet-Rgs2hi (dark blue) (b), Rgs2−/−/ePet-Rgs2lo (light magenta) vs. ePet-Rgs2lo (magenta) (c), and Rgs2−/−/ePet-Rgs2hi (light blue) vs. ePet-Rgs2hi (dark blue) (d). Exogenous expression of RGS2 in serotonergic neurons rescued aggressive behavior in Rgs2−/−/ePet-Rgs2lo mice and more dramatically in Rgs2−/−/ePet-Rgs2hi mice. Results are indicated in the pie graphs as the percentage of displacement per group (winners). Four trials/mouse were performed with random opponents. The number of mice tested/group is indicated within parentheses

RGS2 overexpression in 5HT neurons increases neural activity

Several studies have shown that pharmacological or genetic reduction of 5HT or their receptors, in particular the 5HT1AR and 5HT1BR, can lead to aggressive behavior in mice and men34. Chronic or acute reduction of serotonergic activity by exogenous expression of 5HT1ARs or treatment with agonists in mice also led to an enhancement of aggression and suppression of 5HT neuron firing35. To investigate the physiological impact of RGS2 exogenous expression in serotonergic neurons, we performed in vivo extracellular recordings from DRN neurons in anesthetized mice. These neurons were selected for broad spikes,slow and regular firing and should contain between 60 and 80% of serotonergic neurons36,37,38,39,40,41. DRN neurons from exogenously expressing ePet-Rgs2hi mice showed a higher firing frequency in contrast to Rgs2−/− mice, which demonstrated a lower frequency and precision of firing compared to controls (Fig. 6c–d). Moreover, exogenous expression of Rgs2 in Rgs2−/− serotonergic neurons was able to recover DRN (serotonergic) neuron frequency and precision of firing to control levels (Fig. 6c–d).

Enhanced frequency of serotonergic neuron firing in mice overexpressing RGS2 specifically in seronergic neurons. a Representative traces from controlhi, ePet-Rgs2hi, Rgs2−/−, and Rgs2−/−/ePet-Rgs2hi serotonergic neuron firing patterns. Traces were measured from extracellular in vivo recordings of serotonergic neurons in anaesthetized mice (scale bar: voltage [a.u.] arbitrary units, 5 s). The mean firing rates (b), coefficient of variation of mean interspike interval (CV; c), and coefficient of variation of adjacent intervals (CV2; d) were analyzed from recorded cells. Serotonergic neurons from ePet-Rgs2hi (dark squares) mice exhibited a higher firing frequency compared to Rgs2−/− (grey diamonds) serotonergic neurons, which displayed slower firing rates and increased CVs. The number of cells analyzed are reported within parentheses for each mouse line. Mice (≥3) were tested per line. Data reported as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was evaluated with ANOVA (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001)

We were also able to confirm increases in neural activity by c-fos expression in the DRN after 7 days of resident intruder assays. Not surprising, control and Rgs2 overexpressing and rescue lines displayed a similar rise in DRN c-fos induction (as seen in firing frequencies) following resident intruder assays compared to no resident intruder encounters, but decreases in Rgs2−/− mice (Fig. 7a, b). Two important studies using optogenetic and pharmacogenetic control of the VMHvl identified it as an important locus for eliciting aggressive behaviors in mice42,43. Furthermore, removing inhibitory inputs into the VMHvl glutamatergic cells by lesioning the lateral septum GABAergic inputs increased aggression in mice44. To investigate if the neuronal activity is augmented in the VMHvl of Rgs2-overexpressing mice, we measured c-fos levels in the VMHvl before and after resident intruder tests. Indeed, c-fos induction in control and Rgs2-overexpressing mice were robust in the VMHvl (Fig. 7a, c). Rgs2−/− mice displayed a decrease in VMHvl c-fos induction following resident intruder assays compared to the Rgs2-overexpressing and control lines. Collectively, these data show that exogenous expression of Rgs2 in serotonergic neurons enhances their firing frequencies and maintains their precision of firing. Furthermore, exogenous expression of Rgs2 in serotonergic neurons increases the overall neuronal activity of the DRN and VMHvl following aggressive induced behavior in mice.

Exogenous expression of RGS2 in serotonergic neurons induces c-fos expression in the dorsal raphe nucleus (DRN) and ventrolateral part of the ventromedial nucleus hypothalamus (VMHvl). (a) Representative images of the DRN, higher magnification of boxed DRN area, VMH, and a higher magnification of the VMHvl area from controlhi, ePet-Rgs2hi, Rgs2−/−, and Rgs2−/−/ePet-Rgs2hi mice following 7 days of resident intruder tests. Asterisk represents the analyzed VMHvl region. Increased relative number of cells expressing c-fos after 7 days of resident intruder testing compared to day 0 (naive) in the DRN (b) and VMHvl (c) from controlhi (black circles), ePet-Rgs2hi (dark squares), Rgs2−/−/ePet-Rgs2hi (light squares), and Rgs2−/−(grey diamonds) mice. The number of slices analyzed is reported within parentheses for each mouse line. Mice (≥3) were tested per line. Data were reported as the average total number of c-fos-positive cells/slice within parentheses for each genotype, mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was evaluated with ANOVA (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001)

RGS2 expression in 5HT neurons attentuates GPCR-mediated Ca2+ spikes

Serotonergic activity is in particular regulated by 5HT1A and 5HT1B autoreceptors coupling to the Gi/o pathway as well as other modulatory transmitter systems such as the noradrenergic system coupling to Gi/o and Gq/11 pathways27,37,40,45,46. 5HT1A are localized somatodendritically and reduce serotonergic activity by activation of G protein-coupled inward-rectifying potassium channels (GIRK). 5HT1B receptors are localized at the presynaptic terminal, inhibit presynaptic Ca2+ channels, and therefore 5HT release onto 5HT neurons, thus reducing autoinhibition and increasing serotonergic activity. α1ARs coupling to the Gq/11 pathway increase serotonergic activity26. RGS2 has been shown to block Gq/11 and accelerate and attentuate Gi/o signals in a receptor-specific manner47. Therefore, we investigated if RGS2 affects GPCR modulation of serotonergic activity. We infected DRN neurons with the Ca2+ indicator GCaMP6 and compared Ca2+ spikes before and after application of 5HT1A, 5HT1B, and α1AR receptor (α1AR, Gq/11-coupled GPCR) agonists in DRN brain slices (Fig. 8). We observed that a much higher percentage of GCaMP6-infected neurons were silent in brain slices from Rgs2−/− mice in comparison to wild type or ePet-Rgs2hi (Fig. 8a–c). Application of the 5HT1A agonist 8-hydroxy-DPAT (8-OH-DPAT) decreased the rate of Ca2+ spikes in controlhi and ePet-Rgs2hi, as well as Rgs2−/− mice (Fig. 8d). In contrast, the 5HT1B agonist increased the firing rate drastically for Rgs2−/−, moderately for controlhi mice, and had no effect on ePet-Rgs2hi (Fig. 8e). Application of the α1AR agonist also increased Ca2+ spikes in Rgs2−/−and wild-type slices, but not in ePet-Rgs2hi (Fig. 8f). Thus, exogenous expression of RGS2 selectively modulates intrinsic GPCR signals in serotonergic neurons.

Exogenous expression of RGS2 in serotonergic neurons accelerates GPCR-mediated calcium signals in the DRN. a Representative calcium images and time-dependent changes in calcium fluorescence from a controlhi, ePet-Rgs2hi, and Rgs2−/− cell in the DRN during inactive and active states. Rgs2−/− cells showed minimal changes in calcium levels compared to increased calcium signals in controlhi and ePet-Rgs2hi cells in the DRN. b Calcium spike frequency and c percentage of active cells in the DRN from controlhi (circles), ePet-Rgs2hi (squares), and Rgs2−/− (diamonds) slices. (Note that neurons with a Ca2+ half spike width >5 s were excluded from calculating the mean calcium spike frequency in b; Supplementary Fig. 1A–C.) Calcium spike frequency of cells in the DRN before (closed, −) and after (open, +) application of d 5HT1AR (8-OH-DPAT), e 5HT1BR (CP93129), and f α1 adrenergic (phenyephrine) receptor agonist from controlhi (circles), ePet-Rgs2hi (squares), and Rgs2−/−(diamonds) slices. Number of cells is reported within parentheses for graphs b and d–f. Number of independent experiments is reported within parentheses for graph c. Data are reported as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was evaluated with ANOVA (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001)

Discussion

In the present study, we demonstrate that RGS2, a member of the small RGS family, drives male aggression through the serotonergic system. Exogenous expression of RGS2 exclusively in serotonergic neurons elevated the duration and number of attacks, decreased the latency of attacks, and increased the displacement of male mice in the tube dominance test. Moreover, we were able to rescue the docile phenotype in Rgs2−/− mice by overexpressing RGS2 only in serotonergic neurons. Aside from ePet-Rgs2hi mice spending more time in the center of the open field test, we did not observe any changes in anxious or depressed behavior in the Rgs2-overexpressing and rescue mouse lines compared to their respective control littermates. Our data identify a critical neuronal population, that is, serotonergic neurons in the DRN, where RGS2 modulates male aggression but not anxiety.

This result is in particular surprising, since RGS2 has been implicated to be involved in anxiety- and depression-related disorders in mice and men. Mouse models knocking out Rgs2 show increased anxiety and decreased aggression, and, more recently, heightened neophobia and fear learning7,21,48. Furthermore, extensive human genetic association studies implicate Rgs2 to anxiety, panic, and post-traumatic stress disorders10,11,12,13,14,15,16. Previous investigations suggest that individuals with depressed Rgs2 levels may be potentially at risk for anxiety- or depressive-like related disorders, which can manifest aggressive behavior. A patient study from suicide victims observed increased levels of RGS2 in prefrontal cortex and amygdala regions, which may suggest that anxiety- and depression-related disorders in humans could be mediated through other areas of the brain49. Moreover, linkage studies in humans with RGS6, 7, 8, 5, 19, and 12 implicate their involvement in anxiety, depression, bipolar disorders, and/or schizophrenia. Since only Rgs2, 13, 14, and Gα-interacting protein (Gaip) mRNAs were found in the DRN rat brain, other RGS proteins may be mediating their depressive and anxious behaviors outside the DRN, such as via the nucleus accumbens, amygdala, prefrontal cortex, or hippocampus49,50. Besides a plethora of data linking changes in 5HT levels to anxiety phenotypes, our data suggest that RGS2 modulates anxiety outside the serotonergic system.

The use of germ-line knockout mice for our rescue experiments with a transgenic line may present problems due to the different original backgrounds of the mice. For example, the Rgs2−/− mice originate from a 129 strain and the transgenic Rgs2 overexpression lines from a mixed background. Although they were both backcrossed for more than 17 generations in the C57/Bl6 background, genes from the original knockout, 129 strain in the flanking region and genetic background, or position effects from the transgenic line may contribute to the phenotype and physiology of the knockout and rescue mice51,52. Another caveat of behavior studies is the use of littermate controls and nulls, which may alter aggressive behavior due to the postnatal influences from their siblings52. Hence, the interpretation and translation of the data must be made with caution due to potential developmental adaption and physiological compensation secondary to the loss of the key gene during development53.

We observed in our study that RGS2 determines the spontaneous activity and precision of serotonergic neuron firing in vivo. High expression of RGS2 increases the precision and frequency of serotonergic firing, while serotonergic neurons with low levels/no expression of RGS2 reveal a lower, more irregular firing frequency. We also observed that the level of expression of RGS2 determines the amount of 5HT1B, but not 5HT1A, modulation of Ca2+ spikes. 5HT1B receptors are localized at the presynaptic terminal of serotonergic neurons. 5HT1B receptors activate the Gi/o pathway and inhibit presynaptic Ca2+ channels leading to a reduction of 5HT release. Axon collaterals of serotonergic projections back propagate onto 5HT neurons and downregulate the spontaneous activity of 5HT neurons. Therefore, 5HT1B receptor agonists increased DRN cell firing in wild-type mice, but not in 5HT1B-knockout mice54,55. In addition, expression of RGS2 at presynaptic terminals of serotonergic neurons predict an increase in the 5HT release, since RGS2 has been shown to increase synaptic transmitter release probability by downregulating the Gi/o-mediated presynaptic Ca2+ channel inhibition at hippocampal autapses5. The downregluation of the Gi/o-mediated presynaptic Ca2+ channel inhibition is also reflected in the absence of the 5HT1B agonist effects in ePet-Rgs2hi mice since RGS proteins inhibit G protein signaling and/or the acceleration of signal termination56 (see below).

Based on our previous study, we hypothesize that 5HT release in serotonergic neurons in the presence of RGS2 is increased and involves the RGS2-mediated attenuation of 5HT1B receptor responses. However, this has to be demonstrated in in vivo recordings from behaving animals and has to be compared to studies of 5HT1B autoreceptor knockout mice, which reveal an anti-anxiety and anti-depressant phenotype rather than an aggressive phenotype, which is observed in 5HT1B forebrain-knockout mice57,58.

RGS2 not only accelerates the Gi/o pathway but also act as a GTPase-activating protein on the Gq/11 pathway47. In fact, expression of RGS2 in Xenopus oocytes completely suppresses the Gq/11-induced activation of the Ca2+-activated Cl− conductance59. We observed a similar effect for the α1AR receptor modulation of Ca2+ spike activity in serotonergic neurons, which is abolished by a high expression of RGS2. RGS2 has been shown to specifically interact with α1AR receptors via sphinophilin. This RG2/spinophilin interaction drastically attenuate/block adrenaline-induced α1AR receptor signaling in a concentration-dependent manner, which is not observed in cells from Rgs2−/−mice60.

RGS proteins act as GTPase-activating proteins, which accelerate the hydrolysis of bound GTP on the G protein α-subunit. Physiologically this leads either to the inhibition of G protein signaling or the acceleration of signal termination56. Importantly, modulation of the GPCR signal can be GPCR/RGS specific, leading to the control of a subset of GPCR signal within a neuronal/cellular population in RGS concentration-dependent manner61. Since Rgs2 is an IEG, which is dynamically upregulated during activity and targets specific GPCRs and signaling pathways, one can hypothesize that the upregulation of RGS2 in 5HT neurons, for example, during stress, will shift the serotonergic modulation in the brain to higher aggression.

For example, the locus coerulus (LC) and the raphe nuclei reveal extensive inhibitory interconnectivity. 5HT2 receptors on the prolactin-releasing hormone nucleus drive the main inhibitory input to the LC. In return, the LC acts via inhibitory α2 and excitatory α1 adrenoceptors on the DRN62. Since RGS2 seems to dampen adrenergic signaling (Fig. 8) and increase 5HT release, one could postulate an increased 5HT tone within the aggression circuit5.

There is an abundance of reports in humans and mice that led to the hypothesis that low 5HT levels as a trait-like phenomenon are associated with aggressive behavior24,34,63,64. For example, patients with high level of aggressive and violent behavior have low cerebrospinal fluid levels of 5HT metabolites20. Deletion of the majority of 5HT neurons in the mouse brain leads to a reduction of brain 5HT levels and an increase in aggression25.

In contrast, during the performance and expression of aggressive behavior, 5HT levels have been shown to be increased63. For example, activation of GABAA or 5HT1A receptors in the DRN, which leads to the inhibition of 5HT neuronal activity, decreases aggressive behaviors, and high-aggressive vs. low-aggressive rats reveal an increased number of c-fos- positive 5HT neurons in the DRN and medial raphe nuclei categorized by their performance in the residence intruder test65. Rats and mice exposed to aggressive and agonistic encounters also reveal an increase in c-fos-positive 5HT neurons or DRN neurons66,67. In addition, acquisition of dominance behavior in female hamsters has been associated with activation of DRN 5HT neurons and 5HT1A agonists injected into the hypothalamus or systemically administered fluoxetine increases aggression (note that male hamsters reveal the opposite behaviors)68. Social interaction with an unfamiliar partner and area also results in an increase in extracellular 5HT levels in the ventral hippocampus69.

Species-specific aggression as tested with the resident intruder and tube dominance test involves a stress (neuroendocrine) response and can be divided into different behavioral states, that is, predisposition, social engagement, aggressive interaction, and establishment of social rank70. Aggressive interaction induces an immediate stress response accompanied with high 5HT levels in both dominant and subordinate animals. It has been suggested that dominant animals have immediate and stronger endocrine (i.e. 5HT) responses during social engagement, the time before aggressive interactions. Therefore, our results may suggest that RGS2 is increasing 5HT release in particular during initiation of aggression. Since RGS2 is speeding up GPCR signals by accelerating the GTPase activity of, in particular, Gi/o proteins and attenuating a specific subset of GPCR signals, 5HT neurons should respond much faster and with higher amplitudes to changes in the neuroendocrine response selected for increased aggressive behavior.

We observed in our study that c-fos staining in the DRN is increased after aggressive behavior in ePet-Rgs2hi-expressing mice, and decreased in Rgs2−/− mice. Surprisingly, there was only a tendency of increased c-fos expression in ePet-Rgs2hi-expressing mice compared to controlhi-expressing mice, despite persistently augmented aggressive behavior. Since the aggressive behavior of ePet-Rgs2hi mice peaked after 7–8 days of resident intruder encounters, perhaps c-fos expression levels adapted or peaked earlier in both lines as described previously in a similar study in rats71. In this study, they reported changes in the c-fos expression patterns in specific regions of the brain after 10 vs. 1 encounter to a resident intruder. Certain brain regions remained unaltered, while others increased in c-fos expression. Interestingly, the c-fos activity in the DRN continued to increase following the 10th encounter. C-fos is an IEG and activated by increased neuronal activity. Thus, the results suggest that the DRN neuronal circuit is activated by aggression. Increased c-fos expression in serotonergic neurons has also been observed in highly aggressive vs. low aggressive rats after the resident intruder test65. We observed and increased c-fos staining in serotonergic and non-serotonergic neurons in the DRN.

Upregulation of 5HT neuronal activity during aggression may involve glutamatergic and GABAergic input into the DRN and recruitment of local feedforward and feedback circuits. For example, increased glutamate release causes a phasic increase of 5HT release from DRN 5HT neurons and is observed during escalated aggression. The process may involve activation of GABAB receptors localized on non-serotonergic neurons in the DRN, which leads to an increase in glutamate release72.

The ventromedial prefronal cortex (PFC) sends direct glutamatergic input into the DRN, which drives c-fos expression and synaptic transmitter release, particularly in GABAergic neurons73. However, other studies suggest that synaptic input into the DRN from the PFC is bilaterally organized and innervates both GABAergic and 5HT neurons74. In addition, other brain areas have been identified, which directly innervate the DRG and reveal increased c-fos activity during aggressive behavior, such as the PFC, the ventromedial and lateral hypothalamus, the amygdala, and the locus coeruleus75,76. These areas send glutamatergic projections (PFC and LhB) and GABAergic and glutamatergic projections (lateral hypothalamus, preoptic area, substantia nigra) to GABAergic and 5HT neurons in a brain region-specific manner with defined spatial organization within the DRN74,77.

Methods

Real-time qPCR

To compare the relative mRNA levels of Rgs2 and Rgs4 in hippocampal and serotonergic neurons, total RNA was isolated from 21 days in culture hippocampal or embryonic 12.5 (E12.5) serotonergic neurons with RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen Inc.) and purified with on-column DNase digestion using RNase-Free DNase Set (Qiagen Inc.). Continental cultures of hippocampal neurons were prepared according to a modified version of published procedures from mouse pups (P0–3)78,79. Dissociated serotonergic neurons were previously enriched with FACS (of live cells) from ePet-YFP+ mice where serotonergic neurons are expressing YFP30.

For real-time PCR, 1 mg of RNA was used for reverse transcription with Advantage Real Time for PCR Kit (BD Biosciences) to generate 100 μl complementary DNA (cDNA). Three microliters of the final real-time product was used for real-time PCR for Rgs2, Rgs4, ePet-1 (serotonergic specificity), Tph2 (serotonergic specificity), and β-actin (loading control). 18S RNA was used in a 1:100–300 dilution as internal control and normalized to the 18S RNA found in neurons from wild-type mice. Real-time PCR quantification was performed on iCycler Iq Detection System (Bio-Rad) with CYBR Green Assay (Bio-Rad), and cDNA fragments of Rgs2, Rgs4, ePet-1, Tph2, β-actin, and 18S RNA were amplified with primer pairs: Rgs2 forward/reverse: TGATTGCCCAAAATATCCAA/GGGCTCCGTGGTGATCTG; Rgs4 forward/reverse:

AGAAATGGGCTGAATCGTTG/CCTCTCTGGTGCAAGAGTCC; ePET-1 forward/reverse:

GCAGCGGGCAGATCCAGTTG/TGAGCTTGAACTCGCCGTGG; Tph2 forward/reverse: TTTAAGGACAATGTCTATCG/CTGGGAATGGGCTGACCATA; β-actin forward/reverse: CCATCTTGGCCTCACTGTCC/AGCTCAGTAACAGTCCGCCT; 18S forward/reverse: AAACGGCTACCACATCCAAG/CCTCCAATGGATCCTCGTTA. The PCR reactions used a modified two-step profile with an initial denaturation step for 3 min at 95 °C, followed by 40 cycles of 15 s denaturation at 95 °C and 25 s polymerase reaction at 57 °C. The experiments were performed with three independent neuronal cultures in duplicates (n = 6). Specificity of real-time PCR products was documented with gel electrophoresis and resulted in a single product with desired length. The melt-curve analysis showed that each primer pair had a single product-specific melting temperature. All primer pairs have at least 95% of PCR efficiency as reported from the slopes of the standard curves generated iQ software (Bio-Rad, version 3.1). Relative gene expression data was analyzed with 2–ΔΔCT method80.

Mice

Adult male and female mice (Rgs2−/−, ePet-Rgs2lo, ePet-Rgs2hi, Rgs2−/−/ePet-Rgs2lo, controllo, Rgs2−/−/ePet-Rgs2hi, controlhi) were housed on a 12 h light/dark cycle with food and water ad libitum. The present study was carried out in accordance with the European Communities Council Directive of 2010 (2010/63/EU) for care of laboratory animals and approved by a local ethics committee (Bezirksamt Arnsberg) and the animal care committee of North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany, based at the LANUV (Landesamt für Umweltschutz, Naturschutz und Verbraucherschutz, Nordrhein-Westfalen, D-45659 Recklinghausen, Germany). The study was supervised by the animal welfare commission of the Ruhr-University Bochum. All efforts were made to minimize the number of mice used for this study.

Trangenic mice

The Rgs2−/− mice were a gift from Josef M. Penninger at the Institute of Molecular Biotechnology in Vienna, Austria and backcrossed into C57/Bl6 mice7. For stable integration of Rgs2 constructs into the mouse genome, Rgs2-IRES-GFP was subcloned 3′ to the β-globin minimal promoter and 40 kb serotonergic-specific ePet-1 enhancer in the modified pBACe3.6 vector as previously described29. The pBAC-ePet-Rgs2-IRES-GFP constructs were microinjected into pronuclei by the Case Western Reserve University Transgenic Core Facility (Cleveland, OH, USA). Transgene expression was detected by PCR analysis (forward/reverse: TCTGAACAGGAGCCCATCCC/TTATGCCCAGCCCATCGAAT) and GFP expression in founders. We received nine founder lines, which were positive for the ePet-Rgs2-IRES-GFP BAC constructs. These founder lines were backcrossed for >17 generations into C57/Bl6 mice and evaluated for RGS2/GFP expression in 5HT neurons. Two high-expressing ePet-Rgs2-IRES-GFP founder lines were bred to hemizygosity.

Histology

Fluorescence microscopy was performed as previously described81. Adult male mice (six ePet-Rgs2lo mice, five ePet-Rgs2hi mice) were perfused with 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), pH 7.4, and dissected brains post fixed in the same solution for 1 h. Brains were cryoprotected in 30% sucrose (wt vol−1), 1× PBS overnight at 4 °C. Thirty micrometers of coronal cryostat sections were collected, blocked in 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (fetal bovine serum) in PBST (PBS with 0.1% Triton X-100) for 1 h at room temperature and incubated with a primary antibody against GFP (1:1000 dilution, Frontier Institute) and conjugated with goat-anti-rabbit-A488 secondary antibody (1:1000; Molecular Probes). Images of brain slices were analyzed with a Leica TCS SP5II confocal microscope using a ×20/0.3 NA objective. The intensity of the GFP fluorescence in serotonergic neurons was quantified using NIH Image J.

Single-cell qRT-PCR

Coronal slices (250 μm thick) through the DRN were prepared from male mice by using a modified Leica VT1000S vibrotome. Slices were incubated at 30 °C for 25 min and then maintained at room temperature. During recordings, slices were superfused with artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF; 124 mM NaCl, 3 mM KCl, 1.23 mM NaH2PO4, 26 mM NaHCO3, 10 mM dextrose, 2.5 mM CaCl2, and 1.2 mM MgSO4) equilibrated with 95% O2, 5% CO2 at 30 °C (flow rate, 1–2 ml min−1)82. Coronal slices were prepared from different Rgs2 transgenic mouse lines (≥3 male mice/genotype) expressing YFP under the control of Pet-1 enhancer to allow for better visualization of serotonergic neurons by YFP. To isolate mRNA from YFP+ serotonergic neurons (>3 neurons/mouse), coronal slices were maintained and equilibrated with 95% O2, 5% CO2 at 33 °C in external solution (12.5 mM NaCl, 0.25 mM KCl, 0.125 mM NaH2PO4, 2.6 mM NaHCO3, 2 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgSO4, 2 mM d(+)glucose, pH 7.4). Pulled glass micropipettes (2–4 MΩ) filled with internal solution (125 mM potassium gluconate, 10 mM HEPES, 4 mM NaCl, 0.2 mM EGTA, 2 mM MgCl2, 4 mM ATP, 0.4 mM GTP, 10 mM phosphocreatine, 10 mM KOH, pH 7.3) were used to patch individual neurons and remove cytoplasm-containing mRNA. cDNA was transcribed with SuperScript III First Strand Synthesis System with oligo (dT) primers according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Invitrogen, Life Technologies). Serial dilutions from 20 to 24 were prepared from reversely transcribed cDNA. Rgs2 and Tph (internal loading control) were amplified using Red Load Taq Master (Jena Bioscience) from cDNAs by quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR). Duplicate qRT-PCRs were performed for each cell. Relative RNA expression levels were calculated as a ratio of the Rgs2 and Tph band intensities with NIH Image J. The background intensity of each gel was also factored into the calculation to eliminate exposure differences between gels. The following oligonucleotide primers were used for qRT-PCR: Rgs2 forward/reverse: GGCAGAAGCATTTGATGAAC/TGAAGCAGCCACTTGTAGCC; Tph forward/reverse: TGTGGCCATGGGCTATAAAT/TGTAGAGGGGGTCGGAGC.

Behavior tests for aggression

Resident intruder test: Resident male mice were single housed for at least 14 days before testing and at least 5 days without cage cleaning to facilitate territorial behavior. Resident mouse cages were not cleaned for the entire testing session. Six- to eight-week-old resident intruder mice were housed in rat cages in groups of 15 male mice per cage for at least 10 days before testing to allow acclimation to the dark/light cycle. For 10 consecutive days, one male intruder was introduced to a resident intruder cage for 5 min during their dark cycle. The time to first attack, number of attacks, duration of attacks, number of threats, number of tail rattles, and number of bites were video tracked with the Ethovision XT 8.5 software (Noldus) and later analyzed in a blinded fashion.

Resident intruder test with pups: Resident male mice were housed with one female until pups were born. Resident’s female and pups (postnatal 7–10 days old) were separated from the resident with a clear plastic barrier before testing. Resident mouse cages were not cleaned for the 10 days of testing. Six- to eight-week-old resident intruder mice were housed in rat cages in groups of 15 male mice per cage for at least 10 days before testing to allow acclimation to the dark/light cycle. For 10 consecutive days, one male intruder was introduced to a resident intruder cage for 5 min during their dark cycle. The female and pups were present during the trial and separated from the males by an olfactory permeable partition. The time to first attack, number of attacks, duration of attacks, number of threats, number of tail rattles, and number of bites were video tracked with the Ethovision XT 8.5 software (Noldus) and later analyzed in a blinded fashion.

Tube dominance test: Aggression was tested by using displacement from a plastic tube (30 cm long and 3.0 cm diameter). Pairs of male mice were released into either end of the tube. The first mouse to exit was the “loser.” A maximum session of 10 min was performed and 6 trials with randomized opponents. In the event that both mice remained in the tube for the entire 10 min or both mice exited the tube at the same time, this was considered a “tie.” The plastic tube was cleaned between subjects with 70% ethanol. Number of winners per group is represented as a percentage of the total number trials.

Behavior tests for anxiety

Open field test: The open field arena consisted of an acrylic chamber (30 × 30 × 30 cm3; Noldus), subdivided into a center (14.5 × 14.5 cm2) and border region, which was brightly illuminated by several 75 W incandescent bulbs mounted above the arena. Mice were placed into the center of the open field and the following parameters were video tracked for 15 min with the Ethovision XT 8.5 software (Noldus): time spent in the center, time spent in the border, total distance traveled, and border-to-center transitions. The apparatus was cleaned between subjects with 70% ethanol. For each mouse data were averaged from three trials.

Elevated plus maze test: A modified version of the elevated plus maze was designed according to Pellow et al83. A maze consisting of two, 33 × 6 cm2 open arms, two 33 × 6 × 16.5 cm2 closed arms, and a 6 × 6 cm2 open center was elevated 43 cm above the floor. Mice were acclimated to the behavior lab 60 min before testing. During the 5 min testing period, the following parameters were video tracked and analyzed with Ethovision XT 8.5 software (Noldus): number of entries into the closed arms, open arms and center, time spent in the closed arms, open arms and center, number of head-dips, number of urine puddles, and number of fecal pellets. The maze apparatus was cleaned between subjects with 70% ethanol. For each mouse data were averaged from three trials.

Place preference test: The place preference test, also known as the light/dark mouse exploration test was created according to the modified specifications as Crawley and Goodwin84. Briefly an open field arena (30 × 30 × 30 cm3) was divided into two arenas, an open, light arena and a dark closed arena consisting of a black infrared see through plexiglass box with an opening (30 × 15 × 30 cm3). The light arena was brightly illuminated by 75 W incandescent bulbs mounted above the arena. Mice were placed into the right corner light arena and the following parameters were video tracked with an infrared camera for 5 min with the Ethovision XT 8.5 software (Noldus): time spent in the light and dark arena and the number of transitions between the light and dark arenas. The arenas were cleaned between subjects with 70% ethanol. For each mouse data were averaged from three trials.

Novelty suppressed feeding test: Mice were deprived of food for 24 h before testing with water available ad libitum. A familiar food pellet (weighing ~2 g) was placed in the middle of a new aversive environment (arena: 30 × 30 × 30 cm3), brightly illuminated with two 75 W incandescent bulbs. Mice were placed into a plastic tube in the right corner of the arena, which was removed at the start of the test. The task ended when the mice first fed, defined as biting the food pellet with use of the forepaws. The latency to start feeding served as a measurement of anxious behavior. Subjects were recorded by a video camera for further analysis. Mice were allowed to consume food an additional 5 min in the arena before returning to home cages. Food consumption was measured for potential feeding differences among test groups.

Behavior tests for depression

Force swim test: Mice were placed in a 5 L beaker with a 17 cm diameter and water (23−25 °C) to a depth of 20 cm85. Mice were placed in the water undisturbed for duration of 6 min. Each mouse underwent three trials. The time spent swimming (mobile vs. highly mobile) vs. the time spent floating (immobile) was video tracked with the Ethovision XT 8.5 software (Noldus). The number of fecal pellets per session were also recorded and disposed of after each trial.

Tail suspension test: Mice were resuspended by their tails using adhesive tape for 6 min86. Each mouse underwent three trials. Cumulative mobility (mobile vs. highly mobile) vs. immobility time was video tracked with the Ethovision XT 8.5 software (Noldus).

All transgenic ePet-Rgs2 mouse lines used for behavior studies were hemizygotes. Four- to six-month-old male mice were used for behavior experiments. All mice were single housed in the behavior lab for the duration of the testing period. For the aggression tests, male mice were single housed for at least 4 weeks before testing. Cleaning of the cages was executed at least 2 days prior to testing and not during the testing period to facilitate territorial behavior. Anxiety tests were performed during the light cycle, whereas the aggression tests were performed during the dark cycle of the mice. Mice acclimated 14 days to the dark/light cycle and behavior lab before testing. Data acquisition was performed using a video recording system and Ethovision tracking software. All statistical analyses were calculated by means of one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Significance for comparisons: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001. Results are presented as mean ± SEM from all trials.

Extracellular in vivo recordings of serotonergic neurons

Recordings have been previously performed and described87,88,89. Briefly, adult male mice (≥3 mice/genotype) were anesthetized with 1.5–2% isoflurane. A sagittal incision along the mid-line was performed to expose the cranium and a window 4.0 mm caudal from bregma to access the dorsal raphe region. A multi-electrode device (“Eckhorn microdrive,” Thomas Recording, Giessen) was used to monitor single neurons within the DRN. Single-cell activity was sampled with high temporal resolution (32 kHz) and analyzed offline for spike detection. Alternatively, signals of multiple electrodes were routed through an on-line spike sorter (Plexon, Dallas, TX) and time markers for each detected action potential were stored. Recordings were performed in naive, anesthetized animals in the dorsal raphe. The position of the dorsal raphe was determined according to the xyz coordination of mouse brain (anterior-posterior (AP): −4.1; medial-lateral (ML): 0.0; dorso-ventral (DV: −1.7 to 2.5 mm).

In the offline data analysis, single unit action potentials were detected with custom-made software implemented in Matlab. Possible serotonergic neurons were identified using the classic criteria, broad spikes and slow (around 2 Hz), regular firing, established previously36,37. According to Beck et al.38 and Kirby et al.38,39 error rates using AP duration as a criteria to distinguish serotonergic from non-serotonergic neurons in the DRN are around 20–40%.

Baseline spike trains were analyzed for mean firing rate and spike width. To quantify the spike train regularity, coefficients of variation (CV) of interspike intervals (ISIs) were calculated. Additionally, the CV for adjacent intervals, CV2 ([2(∆ti+1 − ∆ti)] (∆ti+1 + ∆ti)−1), of ISIs were calculated88. An average of CV2 over n estimates the intrinsic variability of a spike train, nearly independent of slow variations in average rate. All statistical analyses were calculated by means of one-way ANOVA. Significance for comparisons: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001. Results are presented as mean ± SEM. Exponential fit of activity after stimulation onset and offset was made with IgorPro (WaveMetrics, Portland, OR, USA).

C-fos induction studies

Rescue mouse line Rgs2−/−/ePet-Rgs2hi, littermate controlhi, Rgs2−/−, and ePet-Rgs2hi mice were introduced to an intruder for 0 (naive) or 7 days. Ninety minutes after exposure to the intruder, mice were anesthetized and perfused with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS, pH 7.4, and dissected brains were post fixed in the same solution for 1 h. Brains were cryoprotected in 30% sucrose (wt/vol), 1× PBS overnight at 4 °C. Forty-five micrometers of coronal sections were collected, blocked in 4% FBS in PBST for 1 h at room temperature and incubated with primary antibodies, rabbit anti-c-fos(1:1000 dilution, Santa Cruz), and secondary antibodies, goat-anti-rabbit Dylight 649 (1:1000; Molecular Probes), for 2.5 h at room temperature or overnight at 4 °C. Brain slices were mounted with Roti-Mount FlourCare DAPI (Roth) to identify the nucleus. Images of brain slices were analyzed with a Leica TCS SP5II confocal microscope using a ×20/0.3 NA objective. The number of slices analyzed is reported in the bars for each mouse line. Mice ≥3 were tested per line. Data were reported as the average total number of c-fos-positive cells/slice for each genotype, mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was evaluated with one-way ANOVA (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001).

Intracranial virus injections

GCaMP viruses were injected in anaesthetized adult mouse brains in the dorsal raphe90,91. All mouse lines were injected with pAAV.Syn.GCaMP6f.WPRE.SV40 (Penn Vector Core, Philadelphia, PA), except for ePet-cre mice, which were injected with pAAV.CAG.Flex.GCaMP6f.WPRE.SV40 (Penn Vector Core, Philadelphia, PA) for 5HT-specific neuron expression. The position of the dorsal raphe was determined according to the xyz coordination of mouse brain (AP: −4.1; ML: 0.0; DV: −1.7 to 2.5 mm). Mice were deeply anesthetized with 1.5–2.0% isoflurane and placed into a stereotactic frame (Narishige, Japan). The skin was opened with a sagittal incision along the mid-line. A small craniotomy was performed and 0.5–1 µl of virus was applied in 100 µm steps using pressure injection in 2 min intervals. A customized glass pipette attached to a 5 ml syringe was used for virus delivery. At the end of injection the skin was sutured (Surgicryl Monofilament, Belgium). After the surgery, animals received subcutaneous injection of carprofen (2 mg kg−1) for analgesia. Animals were placed individually into their home cages to recover and allow for virus expression for 7–14 days.

GCamP6 imaging of DRN neurons in brain slices

Coronal slices (250 μm thick) through the median raphe nuclei were prepared from male mice by using a modified Leica VT1000S vibrotome as described above. Coronal slices were placed in a recording chamber with oxygenated (95% O2, 5% CO2) ACSF. All experiments were performed at 30 °C with a perfusion flow rate of 1–2 ml min−1 82. GCaMP fluorescent neurons were visualized and imaged with a Leica TCS SP5 confocal laser scanning microscope interfaced to a personal computer, running Leica Application Suite Advanced Fluorescence software (LAS AF 2.6) with ×20 objective lens. GCaMP was excited with a 488 nm Argon laser. Emitted light was detected by a PMT after passing through a bandpass filter (505–605 nm). The confocal aperture was wide open during Ca2+ imaging experiments to collect maximum emitted fluorescence. Imaging was performed at 1400 Hz, 371 ms frame−1, and 512 × 512 frames. Drugs were dissolved in ACSF. To determine whether GPCR agonists were able to exhibit evoked Ca2+ elevations, agonists were added directly to ACSF. CP93129 (5HT1B agonist, 50 nM), 8-OH-DPAT (5HT1A agonist, 10 mM), and phenyephrine (α1-AR agonist, 10 μM) were obtained from Tocris. Data were collected from at least four different experiments, using tissue derived from at least four mice for each condition. Ca2+ spikes were detected and analyzed using dedicated software written in Matlab. The fluorescence trace was calculated by measuring the mean fluorescence intensity of the region of interest per frame. Regions of interest were marked before calculating ΔF/F. ΔF/F = (F − F0)/F0, where F is the fluorescence and F0 is the baseline fluorescence. The measured fluorescent intensity was corrected for a baseline value defined as the lowest (<10%) value of the fluorescence measured during the experiment. Ca2+ spikes were analyzed offline and were defined as spikes with a clear onset and offset. The half-width of the spikes were calculated at the median of the spike amplitude.

Statistics and reproducibility

All statistical analyses were calculated with SigmaPlot and Microsoft Excel software unless otherwise stated. Data were initially analyzed for normality by the Shapiro–Wilk test (p ≥ 0.05), and then tested for equal variance with the Equal Variance Test (p ≥ 0.05). If data sets passed both tests, a t test for comparison of two groups or one-way ANOVA (post hoc t test) for comparison of more than two groups was used. Significance for comparisons: *p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.01; ***p ≤ 0.001. Cell counts from specific areas of n ≥ 3 mice are presented as mean ± SEM. For counting, slices were imaged for c-fos-positive cells, followed by manual cell count using NIH Image J. For calcium imaging, spikes were analyzed using NIH Image J (Fiji). In vivo recordings were analyzed by the Matlab software. The n for every experiment is reported in the figures.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The authors declare that all the data supporting the findings of this study are available in the manuscript, figures, and supplementary information files. Source data can be found in Supplementary Data 1. All materials and other data supporting this study are readily available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Heximer, S. P. & Blumer, K. J. RGS proteins: Swiss army knives in seven-transmembrane domain receptor signaling networks. Sci. STKE 2007, pe2 (2007).

De Vries, L., Zheng, B., Fischer, T., Elenko, E. & Farquhar, M. G. The regulator of G protein signaling family. Annu Rev. Pharm. Toxicol. 40, 235–271 (2000).

Zheng, B., De Vries, L., Gist Farquhar, M. & Farquhar, M. Divergence of RGS proteins: evidence for the existence of six mammalian RGS subfamilies. Trends Biochem. Sci. 24, 411–414 (1999).

Ingi, T. et al. Dynamic regulation of RGS2 suggests a novel mechanism in G-protein signaling and neuronal plasticity. J. Neurosci. 18, 7178–7188 (1998).

Han, J. et al. RGS2 determines short-term synaptic plasticity in hippocampal neurons by regulating Gi/o-mediated inhibition of presynaptic Ca2+ channels. Neuron 51, 575–586 (2006).

Hutchison, R. M., Chidiac, P. & Leung, L. S. Hippocampal long-term potentiation is enhanced in urethane-anesthetized RGS2 knockout mice. Hippocampus 19, 687–691 (2009).

Oliveira-Dos-Santos, A. J. et al. Regulation of T cell activation, anxiety, and male aggression by RGS2. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 97, 12272–12277 (2000).

Yalcin, B. et al. Genetic dissection of a behavioral quantitative trait locus shows that Rgs2 modulates anxiety in mice. Nat. Genet 36, 1197–1202 (2004).

Tang, K. M. et al. Regulator of G-protein signaling-2 mediates vascular smooth muscle relaxation and blood pressure. Nat. Med. 9, 1506–1512 (2003).

Hohoff, C. et al. RGS2 ggenetic variation: association analysis with panic disorder and dimensional as well as intermediate phenotypes of anxiety. Am. J. Med. Genet. B https://doi.org/10.1002/ajmg.b.32299 (2015).

Koenen, K. C. et al. RGS2 and generlized anxiety disorder in an epidemilogic sample of hurricane-exposed adults. Depress. Anxiety https://doi.org/10.1002/da.20528 (2009).

Leygraf, A. et al. Rgs 2 gene polymorphisms as modulators of anxiety in humans? J. Neural Transm. 113, 1921–1925 (2006).

Otowa, T. et al. Association of RGS2 variants with panic disorder in a Japanese population. Am. J. Med. Genet. 156B, 430–434 (2011).

Smoller, J. W. et al. Influence of RGS2 on anxiety-related temperament, personality, and brain function. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry https://doi.org/10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2007.48 (2008)

Stein, M. B. et al. Influence of RGS2 on sertraline treatment for social anxiety disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2013.301 (2014).

Amstadter, A. B. et al. Variant in RGS2 moderates posttraumatic stress symptoms following potentially traumatic event exposure. J. Anxiety Disord. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2008.12.005 (2009).

Bartlett, A. A. & Singh, R. H. R. Anxiety and epigenetics. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 978, 145–166 (2017).

Gottschalk MG, D. K. Genetics of generalized anxiety disorder and related traits. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 19, 159–168 (2017).

Nelson, R. J. & Chiavegatto, S. Molecular basis of aggression. Trends Neurosci. 24, 713–719 (2001).

Neumann, I. D., Veenema, A. H. & Beiderbeck, D. I. Aggression and anxiety: social context and neurobiological links. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 4, 12 (2010).

Lifschytz, T. et al. Relationship between Rgs2 gene expression level and anxiety and depression-like behaviour in a mutant mouse model: serotonergic involvement. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 15, 1–12 (2011).

Okimoto, N. et al. RGS2 mediates the anxiolytic effect of oxytocin. Brain Res. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brainres.2012.03.012 (2012).

Pavlov, K. A., Chistiakov, D. A. & Chekhonin, V. P. Genetic determinants of aggression and impulsivity in humans. J. Appl. Genet. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13353-011-0069-6 (2012).

Gross, C. & Hen, R. The developmental origins of anxiety. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 5, 545–552 (2004).

Hendricks, T. J. et al. Pet-1 ETS gene plays a critical role in 5-HT neuron development and is required for normal anxiety-like and aggressive behavior. Neuron 37, 233–247 (2003).

Grafstein-Dunn, E., Young, K. H., Cockett, M. I. & Khawaja, X. Z. Regional distribution of regulators of G-protein signaling (RGS) 1, 2, 13, 14, 16, and GAIP messenger ribonucleic acids by in situ hybridization in rat brain. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 88, 113–123 (2001).

Maejima, T., Masseck, O. A. A., Mark, M. D. D. & Herlitze, S. Modulation of firing and synaptic transmission of serotonergic neurons by intrinsic G protein-coupled receptors and ion channels. Front. Integr. Neurosci. 7, 40 (2013).

Ghavami, A. et al. Differential effects of regulator of G protein signaling (RGS) proteins on serotonin 5-HT1A, 5-HT2A, and dopamine D2 receptor-mediated signaling and adenylyl cyclase activity. Cell Signal. 16, 711–721 (2004).

Scott, M. M. M. et al. A genetic approach to access serotonin neurons for in vivo and in vitro studies. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 102, 16472–16477 (2005).

Wylie, C. J. et al. Distinct transcriptomes define rostral and caudal serotonin neurons. J. Neurosci. 30, 670–684 (2010).

Gerber, K. J., Squires, K. E. & Hepler, J. R. Roles for regulator of G protein signaling proteins in synaptic signaling and plasticity. Mol. Pharmacol. https://doi.org/10.1124/mol.115.102210 (2016).

Hendricks, T., Francis, N., Fyodorov, D. & Deneris, E. S. The ETS domain factor Pet-1 is an early and precise marker of central serotonin neurons and interacts with a conserved element in serotonergic genes. J. Neurosci. 19, 10348–10356 (1999).

Scott, M. M., Krueger, K. C. & Deneris, E. S. A differentially autoregulated Pet-1 enhancer region is a critical target of the transcriptional cascade that governs serotonin neuron development. J. Neurosci. 25, 2628–2636 (2005).

Coccaro, E. F., Fanning, J. R., Phan, K. L. & Lee, R. Serotonin and impulsive aggression. CNS Spectrums https://doi.org/10.1017/S1092852915000310 (2015).

Audero, E. et al. Suppression of serotonin neuron firing increases aggression in mice. J. Neurosci. 33, 8678–8688 (2013).

Aghajanian, G. K., Wang, R. Y. & Baraban, J. Serotonergic and non-serotonergic neurons of the dorsal raphe: reciprocal changes in firing induced by peripheral nerve stimulation. Brain Res. https://doi.org/10.1016/0006-8993(78)91140-X (1978).

Vandermaelen, C. P. & Aghajanian, G. K. Electrophysiological and pharmacological characterization of serotonergic dorsal raphe neurons recorded extracellularly and intracellularly in rat brain slices. Brain Res. 289, 109–119 (1983).

Beck, S. G., Pan, Y. Z., Akanwa, A. C. & Kirby, L. G. Median and dorsal raphe neurons are not electrophysiologically identical. J. Neurophysiol. 91, 994–1005 (2004).

Kirby, L. G., Pernar, L., Valentino, R. J. & Beck, S. G. Distinguishing characteristics of serotonin and non-serotonin-containing cells in the dorsal raphe nucleus: electrophysiological and immunohistochemical studies. Neuroscience 116, 669–683 (2003).

Calizo, L. H. et al. Raphe serotonin neurons are not homogenous: electrophysiological, morphological and neurochemical evidence. Neuropharmacology 61, 524–543 (2011).

Mlinar, B., Montalbano, A., Piszczek, L., Gross, C. & Corradetti, R. Firing properties of genetically identified dorsal raphe serotonergic neurons in brain slices. Front. Cell. Neurosci. https://doi.org/10.3389/fncel.2016.00195 (2016).

Falkner, A. L., Grosenick, L., Davidson, T. J., Deisseroth, K. & Lin, D. Hypothalamic control of male aggression-seeking behavior. Nat. Neurosci. https://doi.org/10.1038/nn.4264 (2016).

Lin, D. et al. Functional identification of an aggression locus in the mouse hypothalamus. Nature https://doi.org/10.1038/nature09736 (2011).

Wong, L. C. et al. Effective modulation of male aggression through lateral septum to medial hypothalamus projection. Curr. Biol. 26, 593–604 (2016).

Morikawa, H., Manzoni, O. J., Crabbe, J. C. & Williams, J. T. Regulation of central synaptic transmission by 5-HT(1B) auto- and heteroreceptors. Mol. Pharm. 58, 1271–1278 (2000).

Day, H. E., Campeau, S., Watson, S. J. Jr. & Akil, H. Distribution of alpha 1a-, alpha 1b- and alpha 1d-adrenergic receptor mRNA in the rat brain and spinal cord. J. Chem. Neuroanat. 13, 115–139 (1997).

Gerber, K. J., Squires, K. E. & Hepler, J. R. Roles for regulator of G protein signaling (RGS) proteins in synaptic signaling and plasticity. Mol. Pharmacol. 1–56, https://doi.org/10.1124/mol.115.102210 (2015).

Raab, A. et al. Increased fear learning, spatial learning as well as neophobia in Rgs2−/− mice. Genes Brain Behav. https://doi.org/10.1111/gbb.12420 (2018).

Senese, N. B. & Rasenick, M. M. T. J. The role of G-proteins and G-protein regulating proteins in depressive disorders. Front. Pharm. 9, 1289 (2018).

Squires, K. E., Montañez-Miranda, C., Pandya, R. R. & Torres, M. P. H. J. Genetic analysis of rare human variants of regulators of G protein signaling proteins and their role in human physiology and disease. Pharm. Rev. 70, 446–474 (2018).

Matthaei, K. I. Genetically manipulated mice: A powerful tool with unsuspected caveats. J. Physiol. https://doi.org/10.1113/jphysiol.2007.134908 (2007).

Eisener-Dorman, A. F., Lawrence, D. A. & Bolivar, V. J. Cautionary insights on knockout mouse studies: the gene or not the gene? Brain Behav. Immun. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2008.09.001 (2009).

Drucker, D. J. Never waste a good crisis: confronting reproducibility in translational research. Cell Metab. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2016.08.006 (2016).

Evrard, A. et al. 5-HT1A and 5-HT1B receptors control the firing of serotoninergic neurons in the dorsal raphe nucleus of the mouse: studies in 5-HT1B knock-out mice. Eur. J. Neurosci. 11, 3823–3831 (1999).

Adell, A., Celada, P. & Artigas, F. The role of 5-HT 1B receptors in the regulation of serotonin cell firing and release in the rat brain. J. Neurochem. 79, 172–182 (2001).

Ross, E. M. Coordinating speed and amplitude in G-protein signaling. Curr. Biol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2008.07.035 (2008).

Nautiyal, K. M. et al. Distinct circuits underlie the effects of 5-HT1B receptors on aggression and impulsivity. Neuron https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2015.03.041, 1–14 (2015).

Nautiyal, K. M. et al. A lack of serotonin 1B autoreceptors results in decreased anxiety and depression-related behaviors. Neuropsychopharmacology https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2016.109 (2016).

Herlitze, S., Ruppersberg, J. P. & Mark, M. D. New roles for RGS2, 5 and 8 on the ratio-dependent modulation of recombinant GIRKs expressed in Xenopus oocytes. J. Physiol. 517, 341–352 (1999).

Wang, X. et al. Spinophilin regulates Ca2+ signalling by binding the N-terminal domain of RGS2 and the third intracellular loop of G-protein-coupled receptors. Nat. Cell Biol. 7, 405–411 (2005).

Xie, G. X. & Palmer, P. P. How regulators of G protein signaling achieve selective regulation. J. Mol. Biol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmb.2006.11.045 (2007).

Ressler, K. J. & Nemeroff, C. B. Role of serotonergic and noradrenergic systems in thepathophysiology of depression and anxiety disorders. Depress Anxiety 12, 2–19 (2000).

Takahashi, A., Quadros, I. M., De Almeida, R. M. M. & Miczek, K. A. Brain serotonin receptors and transporters: Initiation vs. termination of escalated aggression. Psychopharmacology 213, 183–212 (2011).

de Boer, S. F., Olivier, B., Veening, J. & Koolhaas, J. M. The neurobiology of offensive aggression: revealing a modular view. Physiol. Behav. 146, 111–127 (2015).

van der Vegt, B. J. et al. Activation of serotonergic neurotransmission during the performance of aggressive behavior in rats. Behav. Neurosci. 117, 667–674 (2003).

Haller, J., Tóth, M. & Halász, J. The activation of raphe serotonergic neurons in normal and hypoarousal-driven aggression: A double labeling study in rats. Behav. Brain Res. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbr.2005.01.006 (2005).

Haller, J., Tóth, M., Halasz, J. & De Boer, S. F. Patterns of violent aggression-induced brain c-fos expression in male mice selected for aggressiveness. Physiol. Behav. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2006.03.030 (2006).

Terranova, J. I. et al. Serotonin and arginine–vasopressin mediate sex differences in the regulation of dominance and aggression by the social brain. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1610446113 (2016).

Cadogan, A. K., Kendall, D. A., Fink, H. & Marsden, C. A. Social interaction increases 5-HT release and cAMP efflux in the rat ventral hippocampus in vivo. Behav. Pharmacol. https://doi.org/10.1097/00008877-199406000-00007 (1994).

Summers, C. H. & Winberg, S. Interactions between the neural regulation of stress and aggression. J. Exp. Biol. 209, 4581–4589 (2006).

Martinez, M. Adaptation in patterns of c-fos expression in the brain associated with exposure to either single or repeated social stress in male rats. Eur. J. Neurosci. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1460-9568.1998.00011.x (1998).

Takahashi, A. et al. Glutamate input in the dorsal raphe nucleus as a determinant of escalated aggression in male mice. J. Neurosci. https://doi.org/10.1523/jneurosci.2450-14.2015 (2015).

Challis, C., Beck, S. G. & Berton, O. Optogenetic modulation of descending prefrontocortical inputs to the dorsal raphe bidirectionally bias socioaffective choices after social defeat. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 8, https://doi.org/10.3389/fnbeh.2014.00043 (2014).

Zhou, L. et al. Organization of functional long-range circuits controlling the activity of serotonergic neurons in the dorsal raphe nucleus. Cell Rep. 18, 3018–3032 (2017).

Sparta, D. R. & Stuber, G. D. Cartography of serotonergic circuits. Neuron 83, 513–515 (2014).

Takahashi, A. & Miczek, K. A. Neurogenetics of aggressive behavior: studies in rodents. Curr. Top. Behav. Neurosci. 17, 3–44 (2014).

Weissbourd, B. et al. Presynaptic partners of dorsal raphe serotonergic and GABAergic neurons. Neuron 83, 645–662 (2014).

Bekkers, J. M. & Stevens, C. F. Excitatory and inhibitory autaptic currents in isolated hippocampal neurons maintained in cell culture. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 88, 7834–7838 (1991).

Wittemann, S., Mark, M. D., Rettig, J. & Herlitze, S. Synaptic localization and presynaptic function of calcium channel β4-subunits in cultured hippocampal neurons. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 37807–37814 (2000).

Livak, K. J. & Schmittgen, T. D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods 25, 402–408 (2001).

Mark, M. D. et al. Delayed postnatal loss of P/Q-type calcium channels recapitulats the absence epilepsy, dyskinesia, and ataxia phenotypes of genomic Cacna1A mutations. J. Neurosci. 31, 4311–4326 (2011).

Maejima, T. et al. Postnatal loss of p/q-type channels confined to rhombic-lip-derived neurons alters synaptic transmission at the parallel fiber to purkinje cell synapse and replicates genomic cacna1a mutation phenotype of ataxia and seizures in mice. J. Neurosci. 33, 5162–5174 (2013).

Pellow, S. & File, S. E. Anxiolytic and anxiogenic drug effects on exploratory activity in an elevated plus-maze: a novel test of anxiety in the rat. Pharm. Biochem Behav. 24, 525–529 (1986).