Abstract

This paper focuses on a hitherto little-known long (or “Great”) wall that stretches along 737 km from northern Inner Mongolia in China, through Siberia into northeastern Mongolia. The wall was constructed during the late medieval period (10th to 13th century CE) but is commonly called the “Wall of Chinggis Khan” (or ‘Chingisiin Dalan’ in Mongolian). It includes, in addition to the long-wall itself, a ditch feature and numerous associated fortifications. By way of an analysis of this impressive construction we seek to better understand the concept of monumentality and in turn shed light on the wall’s structure, function and possible reasons for its erection. We pose the interesting question of whether any construction that is very large and labor intensive should be defined as a “monument”, and if so, what that definition of monumentality actually entails and whether such a concept is useful as a tool for research. Our discussion is relevant to the theme of this collection of papers in that it addresses the concept of the ‘extraordinary’ as conceived by archeologists. Following our analysis and discussion, we conclude that although size and expenditure of energy are important attributes of many monuments, monumentality (i.e., expression of the extraordinary) is not a binary “either-or” concept. Rather than ask whether the “Wall of Chinggis Khan” was or was not a monument per se, our analysis reveals aspects in which it was indeed monumental and extraordinary, and others in which it was not extraordinary, but rather an ordinary utilitarian artifact.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Monuments are almost by definition “extraordinary” features or structures. According to the common view, monumental works are something intentionally done for non-ordinary purposes. They often require investment of labor and skills that are beyond the ordinary needs for regular day-to-day constructions and they are viewed at the time of creation and thereafter as something unique and beyond the ordinary. This view has been recently supported by statements such as this by Levenson (2019, p. 23): “…monumentality is, in any case, a relational term that defines something through its otherness and opposition to the ‘norm’”. Therefore, addressing monuments and the concept of ‘monumentality’ can help us to clarify the concept of the ‘extraordinary’ and better understand its utility and potential pitfalls as an analytic tool.

When it comes to monumental works, the Great Wall of China is, arguably, the most celebrated monument in human history due to its huge size and the enormous amount of labor invested in its construction. Such features therefore provide an appropriate locus for testing ideas about the concept of monumentality as it relates to extraordinary structures and features. Construction and employment of long (or “Great”) walls occurred periodically in Chinese history from the final centuries BCE up until the 17th century CE (Jing, 2015; Pines, 2018; Waldron, 1990). Scholars have commonly viewed these walls as demarcating an ecological boundary between realms of agricultural societies and those of pastoral nomads (Huang and Needham, 1974, p. 384; Lattimore, 1937). However, the wall we study in this paper is located deep inside the steppe grasslands associated with pastoral communities, and thus it could not have been a borderline separating different ecological zones.

This unique ecological location prompts some basic research questions: What was the purpose of constructing such a large monument in a marginal and sparsely populated region; Who had motivation to invest the substantial amount of resources needed for the construction and maintenance of this wall-system; and how might the concept of ‘monumentality’ help us to better understand this construction in a way that deepens the concept as an expression of what is extraordinary in human life? These questions lead us to examine whether the tendency in archeology to focus on the monumental and the extraordinary is in fact useful for understanding the past or whether it simply obscures that which might have been quite ordinary, despite its impressive size and labor expenditure. The notion of monumentality carries with it the idea of being special and extraordinary, but when confronted with a concrete example of an archeological ‘monument’, we find that the concept breaks down to reveal multiple contexts in which our case study ranges from the extraordinary to the everyday.

Theoretical background

It is beyond the scope of this paper to review the extensive literature on monuments and monumentality in academic fields such as archeology, architecture, anthropology, and art history.Footnote 1 However, at a higher level of generalization it can be said that there are two schools of thoughts on the subject. The first, which we refer to as ‘the materialistic’ view, argues that in spite of the immense variability in what we define as monuments, these structures all share attributes such as large investment of labor and resources, technical skills, elaboration of design, imposing location, and high visibility, etc. (e.g., Buccellati et al., 2019; Brunke et. al., 2016; Trigger, 1990). The second school, which we refer to as ‘the subjective’ view, argues that monuments are related to the feelings and memories they evoke. As such, they also often have a symbolic meaning for societies and individuals. Thus, monumentality is a quality that is related to personal experience, culturally specific conditions and historic context (e.g., Hole, 2012; Osborne, 2014a). According to Osborne (2014a, p. 13), because “…monumentality lies in the meaning created by the relationship that is negotiated between object and person, and between object and the surrounding constellation of values and symbols in a culture”, even a tiny artifact can become monumental. In a similar way, the art historian, Wu Hung, argues that monumentality is a cultural concept that is rooted in specific historic context and as such we need to understand what people of a given time and location conceived monumentality to be, rather than imposing our own views on the past (Wu, 1996).

In our opinion, the disagreement among these two schools is not so much about what ‘monumentality’ is, as much as about what we want the concept of ‘monumentality ‘ to accomplish for us. The ‘materialistic’ school employs ‘monumentality’ as a definition that helps us to analyze objects (buildings, statues, infrastructure projects, etc.) and thereby the information that such objects can provide about the society that constructed them. The ‘subjective’ view, in contrast, hopes to uncover the meaning that these objects once held in the societies that constructed them and for the individuals who used or encountered them in the past. Although there is indeed overlap between these two schools of thought (admittedly somewhat obscured by our simple definitions), we are convinced that at an abstract level they represent the dichotomy between etic and emic viewpoints. While in this study we are more interested in using the concept of ‘monumentality’ (and the ‘extraordinary’) as external tools by which we analyze past societies and their actions, we suggest that such a ‘materialistic’ view will also inevitably shed light on the way people experienced monuments. Contrary to Osborne (2014a, p. 9) who argues that the etic approach is incapable of capturing the effects that the built environment had on people, we think that it is only through such an external analysis that we might hope to understand the complexities involved in the interaction of humans with their environment, including the man-made environment. This is especially true for prehistoric societies, as well as for historic periods for which we may not have very detailed or pertinent historical records.

In order to use monumentality as an analytic tool, we first need to define this complicated term, which, even at the most basic level, turns out to be a difficult task. The complexity of the phenomenon of monumentality and its varied manifestations are acknowledged by most scholars who have written on the subject. It is also clear that some definitional lines, even if they may be somewhat arbitrary, must be drawn. If we accept Levenson’s (2019, p. 19) idea that “…nothing is monumental, and everything is monumental”, then clearly our definition will not be useful for distinguishing or explaining anything. On the other hand, we do not want to return to the ‘check-list’ approach of early scholars such as Gordon Childe (1945).

In this respect, we can agree with Levenson that monumentality is “…a relational term that defines something through its otherness and opposition to the ‘norm’” (Levenson, 2019, p. 23). However, we are in need of a more comprehensive definition that takes this relational aspect into account, but which also provides a more concrete starting point to explore the ‘extraordinary’ quality of monuments. Diverse definitions do exist in the literature; some put more emphasis on aspects related to the construction of a monument, such as the energy expenditure (e.g., Trigger, 1990), while others emphasize the visual effects achieved by the finished monument (e.g., Hageneuer and Schmidt, 2019). But is it possible or useful to set concrete limits, even as a heuristic device, beyond which something cannot be viewed as ‘monumental’? For example, can we say, as suggested above, that a very small artifact should not be considered as monumental? On the opposite side of the spectrum, and more directly pertinent to our topic at hand, can an artifact of daily functional use, even if very large and resource intensive, be considered a monument? In other words, are engineered features such as aqueducts, roads, and defensive walls appropriately considered ‘monumental’ per se? According to Osborne (2014a), size and scale of investment are not enough to define and bestow monumentality. Indeed, none of the many papers in the comprehensive book edited by Osborne (2014b), entitled Approaching Monumentality in Archeology, address such common structures as these. Others, however, argue that even large infrastructure projects, such as water supply and sewer systems, might be considered ‘monumental’ (Brunke et al., 2016, pp. 277–283).

One potential way of constructing a theoretical framework from the various aspects discussed above—i.e., intentions, scale of investment, and visual impact—is by employing the “handicap principle”, otherwise known as costly signaling. This concept, which was developed to explain the evolutionary logic of what seem to be extraordinary traits and behaviors of different animal species (Zahavi and Zahavi, 1997), was adopted early on in fields such as economics and communication (e.g., Spence, 1973). The idea is that when a signal (in our case, the monument) is highly visible to a targeted audience (including competitors), the cost of producing the signal (e.g., investment in the monument) guarantees the fidelity of the information it carries. Put another way, the ability and willingness of the transmitter (i.e., the builder of the monument) to invest such a huge amount of resources beyond any practical need, proves even to a skeptical observer that he or she is not bluffing. At the same time, if the information is effectively transmitted and accepted then the investment is actually economically prudent as it may save a much larger investment, such as conflict, down the line.

This model, which is not terribly different from the more traditional anthropological concept of conspicuous consumption, explains the seemingly senseless expenditure some human societies are willing to invest in wistful behavior, such as large scale feasts or ceremonies. Such investment, it is argued, signals the power and increasing political and social prestige of aspiring leaders (Aranyosi, 1999; Bliege and Smith, 2005). In archeology, this idea has been used to explain large scale expenditure in monumental constructions even during periods of economic pressure (e.g., Glatz and Plourde, 2011; Neiman, 1997; Trigger, 1990; Wright, 2017). However, while costly signaling can serve as a source of inspiration to explain monumentality, archeologists lack the rigorous ability of economists to test such a model with accurate cost-benefit analysis, or to connect it convincingly to evolutionary theory, as done by zoologists (Conolly, 2017).

A more realistic way to approach monumentality in archeology is to identify core aspects of this concept and examine the ways in which they are interconnected and how they are manifested (or not) in concrete case studies (e.g., Burentogtokh et al., 2019; Honeychurch et al., 2009). Such an approach is taken by Brunke et al. (2016, 254–255) who stipulates five major criteria for the identification and study of ancient monuments: Size, position, permanence, investment, and the complexity of the given project. All five categories are relative (e.g., relative size in comparison to other constructions, prominent position relative to the surrounding environment, etc.); but they are also factors that we can quantify and analyze. In the analysis presented below we use these criteria, as well as insights taken form costly signaling theory, as a starting point to assess the so-called “Wall of Chinggis Khan”.Footnote 2

The medieval wall-system

In contrast to the well-known “Great Wall of China” far to the south, our study focuses on a northern system of walls constructed during the late medieval period (10th to 13th centuries CE) in what are today parts of northeastern China, Siberia, and Mongolia. All together, these walls stretch over a distance of at least 3500 km (Jing and Miao, 2008, p. 22); however, some argue that by taking into account all of the parallel lines, the accumulated length is more than 6500 km (Ping, 2008, p. 101), making it one of the longest walls and largest human-made structures. However, in spite of its huge size, the historical documents are silent about the construction of this wall-system. Thus, it is unclear when exactly it was built, who built it, and for what purposes. It is not even clear if all the different wall lines are part of one pre-planned project or whether they represent an accumulation of different projects constructed at different times (within this 300-year span) for different purposes.

While the historic context of the construction of this wall-system(s) is important, due to these many uncertainties we have opted in this paper to focus less on the historically relevant questions, and instead consider the more general issues involving analysis of the wall-system. To ensure that we are analyzing a coherent construction project rather than an agglomeration of different projects we concentrate on one wall section which seems to represent a pre-planned integrated construction. This section, known by its traditional name, the “Wall of Chinggis Khan”, stretches 737 km across the grasslands of the border area between present day Mongolia, Russia, and China (Fig. 1). Besides the mounded wall itself, our section also includes a ditch feature and several auxiliary structures such as rectangular and circular enclosures, some of substantial dimension and suggestive of fortifications or supply depots (Fig. 2). In spite of its impressive size and preservation, relatively little archeological or historical research has been done on this wall-system (exceptions are Baasan, 2006; Lunkov et al., 2011; Ma, 2013). The analysis presented here is based on two field seasons carried out by a joint Mongol-Israeli-American team in Dornod province of northeastern Mongolia (Shelach-Lavi et al., 2020).

In spite of ongoing disagreements, most scholars attribute the construction of the “Wall of Chinggis Khan” to the Khitan-Liao dynasty (907–1125 CE) (Lunkov et al., 2011). The Khitans were a semi-nomadic group that originated in present-day Inner Mongolia. They established their dynasty after the collapse of the Uighur Empire in Mongolia (744–840 CE) and the Tang dynasty of China (618–907 CE). At the end of the first millennium CE, the Khitan conquered large swathes of Manchuria, eastern Inner Mongolia and the Mongolian steppe, to form the Khitan-Liao Empire (Fig. 3). The administration of the Liao dynasty combined Chinese and nomadic elements and was a formidable enemy of the Northern Song (960–1127 CE), the reigning Chinese dynasty to the south. During the early years of the 12th century, the Jurchen peoples of Manchuria, previously vassals of the Liao, united and in a very short period were able to destroy the Liao dynasty and push the Song southward. They followed these successful conquests by establishing the Jin dynasty (1115–1234 CE).

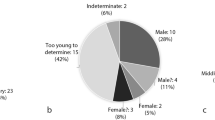

Given this tumultuous political history, it is no surprise that the building of the northern wall-system has been attributed to the Khitans, the Jurchen, and to the later Mongols. Based on a series of radiocarbon dates on samples excavated from both wall sections and from associated structures, our preliminary assessment affirms the consensus of Khitan-Liao period construction (Table 1). The wall is a continuous feature across the open landscape and is visible above ground throughout most of its length, but is currently preserved to a height of no more than 1 m. Using high-resolution satellite images, we were able to trace the entire length of the wall which stretches between the Khentii mountains in the west and the Da Xingan mountains in the east. Along the wall line we identified no fewer than 72 individual auxiliary structures arranged in 42 clusters (Fig. 1). The more or less even spread of these clusters along the line of the wall and the uniformity of each structure’s shape and size suggests a pre-planned and integrated system.

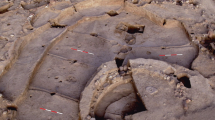

Our team conducted test excavations during the summer of 2019 in and around Cluster no. 24 designed to assess the structure of the wall and the various enclosures nearby. A trench dug through the wall exposed a section of its profile which proved to be constructed of compacted earth layers. However, because it was heavily eroded, it is difficult to reconstruct the original shape and height. On the north side of the wall line our trench exposed a man-made ditch feature that is now filled in by the eroded earth from the original wall. The ditch is about 2 m deep and 2–3 m wide (Fig. 4). It is reasonable to suggest that the earth excavated from the trench was used to build the wall and thus produced a barrier that combined both the depth of the ditch with the height of the wall.

A group of three structures, together comprising Cluster no. 24, located about 200 m south of the wall line was also targeted for excavation. These include a large rectangular enclosure inside which a second, smaller rectangular structure is situated, and a large adjacent circular structure (Fig. 2). The large and small rectangular structures are 108 and 25 m wide, respectively, and the circular structure is 135 m across its diameter. A section dug into the wall of the small rectangular structure demonstrated that it was much more solidly built in comparison to that of the long-wall. Although it was also heavily eroded, the wall of the enclosure is preserved to a height of greater than one meter with clear layers of highly compacted earth mixed with crushed limestone (Fig. 5). The original height of this enclosure wall, and the walls of the larger rectangular structure, must have been significantly higher and more labor intensive than that of the long-wall itself. Another section, dug into the wall of the circular structure, suggests that it was not as high as that of the adjacent rectangular enclosures, but in terms of building technique, was similar in construction and involved the use of an intentionally mixed earth and crushed lime material which was compacted in vertical horizontal layers (Fig. 5). Based on our observations, the walls of the rectangular and circular structures were probably both constructed using the traditional Chinese method of ‘tamped earth’ to compact the sediments and provide a more durable embankment.Footnote 3

Analyzing the monumentality of the medieval wall-system

As a starting point for our analysis of the Medieval Wall-System we consider the five criteria suggested by Brunke et. al. (2016, pp. 254–255); namely size, position, permanence, investment, and relative complexity of the project. The first characteristic, size, seems to be self-evident in this case so we will not discuss it further. We start from estimates of investment in the project and its complexity, and then discuss the permanence and position of the wall-system. We end by addressing additional parameters including the intended function of the wall and surmise the social and political value with which it was originally invested.

How complex and resource intensive was the construction of the wall-system?

Brunke et. al. (2016, p. 255) judge the complexity of a project based on the degree to which: “…the technical knowledge, the artisanal skills and the organizational and logistical effort required to construct the object exceed both qualitatively and quantitatively the levels entailed in construction of a structure reflecting the norm for the surrounding area”. While the technical skills required to construct the wall-system do not seem to be exceptional for what was common for buildings during this period, the logistics of constructing such a project in an area that was remote from the dynastic centers and from concentrations of human labor and resources, must have been immense. Estimating the size of the labor force needed to accomplish such a project is fundamental for our understanding of the complexity of the wall-system and how expensive it was in terms of resource expenditure.

While precise calculation of the amount of labor that went into the construction of the wall-system (comprising both the long-wall and associated structures) is impossible, estimates based on historic sources, ethnographic observations, and experimental archeology can provide approximations that are good enough for the purpose of this study (Abrams, 1994; Abrams and Bolland, 1999; Erasmus, 1965; Shelach et al., 2011; Yuan, 1983). Based on the work of Abrams and Erasmus one of us has previously estimated that a worker can construct 1 m3 of wall, including the excavation of the required earth and the building of the wall itself, in 1.4 work-days (Shelach et al., 2011). However, according to the Han mathematical manual, the Jiuzhang suanshu (九章算術 Nine Chapters on the Mathematical Art), a single conscript worker was expected to excavate, transport and construct 7.55 m3 of tamped earth wall in a month (Shen et al., 1999: 254–260). Thus a single person was considered able to construct 1 m3 of wall in about four days. This is also the estimate presented by Yuan Zhongyi based on his observations of contemporary peasant work. According to his estimate, one person is able to dig 0.5 m3 of earth per day and construct 0.5 m3 of wall per day (Yuan, 1983, p. 45). Of course, these assessments are more accurate for the kinds of conditions, tools and techniques that existed in pre-modern China. However, in order to provide a very general estimate of the cost of constructing the wall line and its associated structures based on the above accounts, we use a range between 1.5 and 4 worker days for the construction of 1 m3 of wall in our analysis. This range includes the digging of earth and the actual construction of the wall, but not the transportation of the soil. Constructing the wall line itself may be closer to the lower estimate because the earth was excavated on the spot (i.e., from the ditch) and was not extensively tamped. In contrast, the building of the adjacent enclosures were more time consuming because the earth was probably transported over greater distances, and the walls were larger and more thoroughly tamped.

As mentioned above, the ditch that runs along the wall line is about 2 m deep and 2–3 m wide (Fig. 4). It was probably slightly wider at the top than at the bottom but, overall it seems to have a volume of about 4 m3 for each meter of wall. Combining the length of the long-wall (737,000 m) and the accumulated length of the walls of the 72 rectangular and circular structures (14,500 m) and multiplying that by 4 (4 m3 of earth per 1 m3 of wall), tallies up to 3,006,000 m3 of earth that the workers had to excavate and from which they constructed the wall-system in total. Based on the calculations above, this would have required between 4.5 million to 12 million work days. If we assume that each worker can work about 350 days a year, this amounts to between 12,857 to 34,355 work years. In other words, a working force of between 13,000 and 35,000 people could construct this wall in about a year. These are, of course, extremely minimalistic estimates. For one thing, the ground in northeastern Mongolia is frozen for about half of each year. Therefore, workers were probably able to excavate the ditch and construct the earthen walls for only six months out of each year, which doubles our estimates for the amount of time needed for the construction. In addition, those numbers reflect only the amount of work directly invested in the construction of the walls. Other types of expenses, such as providing food, water, and clothing for such a large work force in such a remote area would probably have been very high as would other expenses such as producing and transporting the necessary tools and other logistical items, including perhaps even providing military protection. Such associated costs would again likely double the amount of work required for this project. Thus, a realistic estimate would be that a working force of between 13,000 and 35,000 people could have constructed this wall-system in approximately four years.

This estimate certainly represents a substantial expenditure of labor, resources, and time. Using the criteria suggested by Levenson (2019, p. 23), that monumentality should be evaluated through its otherness and opposition to the norm, it is clear that such investment far exceeded the cost of constructing a house or even an entire village during the medieval period in China and Mongolia. On the other hand, for a dynasty such as the Khitan-Liao, this was probably not such an extraordinary project. For example, the Liao history (Liao shi, 遼史) reports that during the second year of the Liao Shengzong emperor’s reign (983–1012 CE), the Liao mobilized 200,000 people to build a mountain road. According to the historic report this huge work force was able to complete the construction in a single day.Footnote 4

The permanence and position of the wall-system

As they do for their other criteria, Brunke et al. (2016, pp. 254–255) define the two concepts of permanence and position in relative terms. They emphasize an object’s exposed position relative to the surrounding buildings and environment (i.e.,position) and its presence within the surrounding area over a long period of time (i.e., permanence). While these definitions are straight-forward enough, the analysis of the wall-system based on these concepts provides somewhat ambivalent results. In considering the permanence of the northern wall, we propose that this idea comprises at least two unrelated aspects: (a) How long did the wall function, and (b) how long did it remain visible in a way that shaped the local environment? Based on our current field work it seems that the wall-system functioned for the duration of the Khitan-Liao period. Charcoal samples taken from the bottom of the ditch feature and the lower levels of the small rectangular enclosure suggest that the construction of Cluster no. 24 likely commenced during the mid 10th or very early 11th century CE. Two later dates from the same enclosure and the adjacent circular embankment fall into the later Khitan period during the 11th and 12th centuries CE, suggesting that activity was ongoing through much of the two century reign of this dynasty (Table 1). Although ceramic shards associated with the Khitan style were found on the surface of all structures that we visited, their density was fairly low (Shelach-Lavi et al., 2020) and the same was indicated by our test excavations. Based on current information and recognizing that five dates can only provide a preliminary assessment, we believe it is likely that all structures at Cluster no. 24 were used contemporaneously but that the phases of occupation were relatively short-term and possibly episodic.

The visual impact of the wall-system is, however, not limited to the time of its use-life. The wall line and especially the associated structures have continued to remain highly visible throughout history and up to the present day (see more about visibility below). It might be said that in many ways this ‘artifact’ shaped the local and perhaps even regional landscape in significant ways. Although the wall is remote from any permanent population centers, the remains of the wall were noted and seen as important landmarks by travelers during ancient and more recent times. This, for example, was probably the wall that the Daoist monk and traveler Qiu Chuji (known by his Daoist name of Master Changchun, 1148–1227 CE) recorded in a remote region of Mongolia during his travels to meet Chinggis Khan (Li, 1931, p. 63). Similarly, during the 18th and 19th centuries European and Russian explorers to the region report seeing the wall line and its associated features on several occasions (Jing, 1982; Lunkov et al., 2011). Our survey and excavations suggest that the structures were visited in later periods and were sporadically used as a focus of feasts or rituals. Even in very recent times, the remains of Cluster no. 27 have been used by the Mongolian military as part of their border outpost.

Addressing the position (or visibility) of the wall-system is also not as clear-cut as one might expect. On the one hand, because it is located in such an open environment where no other permanent structures exist and because the region is relatively flat, the wall and especially the accompanying structures, must have been highly visible. Even today, when the wall and the structures have been considerably eroded away, they are still clearly visible and are easily identified, for example, on satellite images. However, because of the natural environment and the scarcity of local population, such visibility would be true for any structure built in this region. Therefore, the question may be better rephrased as follows: Was the wall and its associated structures placed in such a way that enhanced their visibility, making them clear demarcations on the landscape and apparent from far distances?

To address these questions more systematically we conducted a viewshed analysis of a section of the wall and associated clusters nos. 26–34. Using GIS tools, we compared the area seen from those nine clusters to the area seen from eight points located nearby those clusters but on higher ground (Fig. 6). The difference is quite clear: On average each of the clusters “sees” (and is “seen” from) 137,862 pixels of 30 × 30 m while each of the comparison points “sees” an area almost ten times as large (1,259,007 pixels). Raising the view point height of the clusters by 3 m, on the assumption that people could have used watch towers or other elevated constructions, had a negligible effect on the results. A cross sectional analysis of the geography along a line that connects all clusters confirms a preference to locate these structures at lower elevations in less visible areas (Shelach-Lavi et al., 2020). Such placement of the structures was probably intentional and we thus suspect it had to do with the intended function of the structures and of the wall-system generally (see below). However, in terms of the “position” criterion, it certainly weighs against the idea of the wall as monumental.

Intended function of the wall and the value placed upon it

Intentionality and function, as discussed above, are often part of our understanding of the monumentality of an object or a structure (e.g., Levenson, 2019; Osborne, 2014a). This raises the question of whether the people that constructed a given artifact, feature, or building intended it to impress viewers and evoke memories or emotions? Furthermore, can we describe the intended function that it was supposed to fulfill as unique or ‘monumental’? While scholars disagree about its exact time of construction, all prior research agrees on the function of the medieval wall-system as a fortification built in a time of war (e.g., Lunkov et al., 2011; Ma, 2013; Ping, 2008; Wang, 1921). Warfare is undoubtedly an extraordinary event and its association (and memory) is often related to an aura of monumentality. However, our analysis sheds doubt on this consensus. For one, the actual obstacle that was supposed to stop an invading army—the wall line—was not that formidable. As discussed above, the ditch was probably 2 m wide and 2 m deep and the wall no more than 2 m in height (Fig. 4). Such walls were not a serious obstacle for the armies of the time which could open a passage through them with relatively little effort.

The military function of the wall-system is also contradicted by the location of the associated structures at lower elevations and with minimal control over the extended wall line itself (Fig. 6). Such locations are related to the position of local streams and are probably associated with roads and pathways that connected areas north and south of the wall. Thus we conclude that the wall-system was geared towards controlling and monitoring the movement of people and their pastoral herds, as well as perhaps other movements of civilian populations, such as trade, rather than defending against the attack of large armies. The wall would have served to channel the movement of people and animals to pre-designated crossings where even with a minimal presence of guards they could be monitored and managed effectively (Shelach-Lavi et al., 2020). Such a task, which may have been associated with both controlling and taxing local nomadic communities, might be best described as ‘mundane’ and certainly not as ‘monumental’.

If indeed the wall was not meant to preform ‘monumental’ deeds such as defense during warfare, can we understand the wall-system based upon the costly signaling model? Was it meant to convey a clear and ‘honest’ signal to the local population about the power of the Khitan-Liao dynasty? As suggested above, it is almost impossible for archeologists to test costly signaling hypotheses using a rigorous cost-benefit analysis. Furthermore, costly-signaling is a rather mechanistic approach that, given its pedigree in biological evolution, does a poor job of capturing the dynamics of social and political interaction on the ground. Costly-signaling is a version of McLuhan’s (1964) phrase “the medium is the message” such that the signal, or the message, to be communicated is indeed its great cost of production. This model focuses primarily on the intent of the maker but assumes an effect on the intended audience, which in our case was likely a more complex process involving multiple audiences. Costly-signaling is a simple approach to social dynamics, but it does point our attention to the important issue of perception and audiences and raises the question of in what ways did different communities understand, conceptualize, and perceive this wall? In short, did they view this massive construction as monumental and extraordinary, or did they perceive it in mixed contexts and from multiple perspectives, as our discussion so far would suggest? Again, this is not a question that archeologists can easily decipher given our limited sources of evidence, but examining it closely allows us to pull together what material, historical, and contextual facts are available to evaluate this question of perception and costly-signaling.

We hypothesize two major audiences for whom the signal may have been intended and meaningful: The local nomadic inhabitants of the steppe and diverse members of the political community that made up the Khitan-Liao Empire. Given the first audience, the costly signaling model assumes that the monument was often encountered (i.e., viewed) by the local target population it was intended to impress, and that the message it was meant to convey was clearly understood. The location of the clusters of structures along natural routes of movement is in keeping with these locational criteria and would have been well suited for communities practiced in a tradition of mobile politics (Honeychurch, 2015). These pathway areas are indeed the ideal places at which mobile herding groups could have been exposed to overt messaging and this case would be in line with similar landscape organizations, for example that of monomial stone carvings in Late Bronze Age Anatolia (Glatz and Plourde, 2011). However, in the Anatolian example it is clear how an extensive investment in producing a forceful and ‘honest’ message through stone carving placement would have been beneficial when compared to the much higher cost of deploying administrative or military power. In the case of the Mongolian wall-system, it is not clear how many people would have viewed this structure and, even if they did, when considering the costs of construction as well as those of operating this extensive system, that it would have saved much expenditure at all. Rather, as a message-distribution mechanism, the wall-system would seem to be quite inefficient.

Turning to the second potential audience, we pose the question of whether the investment in such a wall would have had symbolic meaning internally for those upon whom the ruling house depended for political support. This question introduces a body of anthropological theory concerned with symbolic messaging, political theater, and the making of political landscapes as fundamental parts of statecraft (Smith, 2003). In the case of Khitan-Liao politics, Lin (2011) has been one of the most attentive scholars to aspects of the built landscape as overt political and symbolic statement. In particular, Lin focuses on the perception among political constituencies of the construction of massive Khitan walled cites which in many cases were only partially inhabited by pastoral nomadic elites (Lin, 2011, p. 240). In this case, the ‘message’ of the urban center was more important as a legitimizing political statement than was its daily function as a city. The construction of the “Wall of Chinggis Khan” raises similar possibilities for our study given that the vocabulary of wall building had been part of the East Asian imperial tradition for over a millennium prior to the rise of the Khitan-Liao. Therefore, one hypothesis is that the perceptions on the part of the Khitan aristocracy of their leadership and its legitimacy might have been reinforced by such impressive construction projects very much in keeping with expectations for an imperial state. However, turning to the historical texts in search of evidence for such a hypothesis reveals that our wall is never so much as mentioned nor did a single notable personage take credit for its construction. Our case study argues against the logic of both the costly-signaling and political landscape models. Instead, the evidence, once again, encourages us to view the “Wall of Chinggis Khan” as an ordinary and utilitarian feature of the far northern landscape.

Conclusion

The discussion above is somewhat complex and can be seen as taking either multiple perspectives on the status of the wall-system in question or perhaps as merely confusing for a reader. Clearly, according to some criteria the wall-system is ‘monumental’ while according to others it is not. However, to our minds this is in fact an accurate reflection of the concept of monumentality (or the ‘extraordinary’) itself. We probably cannot expect any artifact or building to fit all the different criteria of ‘monumentality’. Rather, we should ask which criteria it does indeed fit and under what conditions or circumstances does such a fit help us to better understand the features or constructions we seek to study. We argue that using the concepts of monumentality and ‘the extraordinary’ in this way, rather than as either/or definitions of exclusion or inclusion, makes them more useful as analytic tools. By addressing the set of questions and criteria as presented here in a thoughtful and systematic manner, we were indeed able to deepen our understanding of the northern wall-system.

At the beginning of this paper we posed the following question: Can we explain an extraordinary expenditure of human labor and resources as resulting, not from extraordinary circumstances and objectives, but as part of that which is merely ordinary? Our reply to this question is a resounding ‘yes’. The wall-system in question was probably constructed to address fairly mundane issues despite its impressive geographic extent and the amount of labor invested in its construction. From the emic perspective of those who built and used this structure and of those whom it was intended to manage, the wall-system was probably not seen as ‘monumental’ but rather as a daily reality. The wall was simply something to pass through in the process of pastoral movements or, on the other hand, a structure to manage such passage in the interest of the state.

On the other hand, from our etic viewpoint, as researchers who strive to understand societies of the past, the construction of this wall was certainly an extraordinary event. Given the perspective of an ‘archeological gaze’ backwards, that which impresses us as scientists is easily imagined as monumental. Perhaps it can be argued that those factors which made the wall-system ‘non-monumental’ at the time of its construction and use—its location in a remote and sparsely populated area and the fact the no one took credit for its construction—are exactly those which make it extraordinary (and by extension ‘monumental’) for us today. Its extraordinary location can be seen from two complementary perspectives: (1) It is very different from the location of any other long-wall (or great-wall) lines in East Asian history; and (2) throughout time, no other structure that required a comparable amount of investment and complex organizational skills, was built in this region. It is these extraordinary traits that are always relative to their immediate setting, that guide our study and understanding of the wall-system. Such observations lend themselves to historically oriented questions: Why was such a monument built during this time and how did the need for such monumentality reflect the unique conditions that must have inspired it? While addressing these questions is beyond the scope of this paper, our ability to articulate them clearly is due to our exploration of the type of monumentality that such a wall-system engenders.

Data availability

The datasets generated during this study are not yet publicly available due but will become available when we finish publishing all of our analyses. It is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Notes

We are limiting ourselves to the definitions of monumentality that focus on material objects. An even broader discussion exists in other fields where the terms monument and monumentality are applied to concepts, acts, persons, written records, etc. (for a survey of those fields see Hogue, 2019).

The name is folkloristic and the wall has no historic connection to Chinggis Khan (Baasan, 2006). It was probably built prior to the birth of Chinggis Khan by the Khitan-Liao dynasty (907–1125). For the sake of objectivity, we will refer to it below as the ‘wall system’ or ‘medieval wall-system’—including in this definition the line of the wall and ditch feature, as well as associated structures.

For description of the ‘tamped earth’ or ‘pounded earth’ (Chinese hangtu 夯土) technique see Shelach-Lavi, 2015, pp. 200–201.

二年秋, 詔修諸嶺路, 昉發民夫二十萬, 一日畢功 (遼史卷七十九 Liao shi, chapter 79). This sentence is perhaps an exaggeration regarding the total number of workers, as well as their ability to complete the work in one day, but there are many other references to large scale work projects in the Liao shi. Archeological work at Liao period city sites located in the central parts of the Liao territory, supply additional evidence for the ability of the Liao to organize and support very large-scale projects (e.g., Neimenggu, 2013).

References

Abrams EM (1994) How the maya built their world: energetics and encient architecture. University of Texas Press, Austin

Abrams EM, Bolland TW (1999) Architectural energetics, ancient monuments, and operations management. J Archaeol Method Theory 6.4:263–291

Aranyosi EF (1999) Wasteful advertising and variance reduction: Darwinian models for the significance of nonutilitarian architecture. J Anthropol Archaeol 18(3):356–375

Baasan T (2006) Chingisiin Dalan gezh iuu ve? [What is the Chingis Wall?]. Admon, Ulaanbaatar

Bliege BR, Smith EA (2005) Signaling theory, strategic interaction, and symbolic capital. Curr Anthropol 46(2):221–248

Brunke H, Bukowiecki E, Cancik-Kirschbaum E, Eichmann R, van Ess M, Gass A, Gussone M, Hageneuer S, Hansen S, Kogge W, May R, Parzinger H, Pedersén O, Sack D, Schopper F, Wulf-Rheidt U, Ziemssen H (2016) Thinking big. Research in monumental constructions in antiquity. eTopoi J Ancient Stud Special 6:250–305

Buccellati F, Hageneuer S, van der Heyden S, Levenson F(eds) (2019) Size matters–understanding monumentality across ancient civilizations. Transcript Verlag, Bielefeld

Burentogtokh J, Honeychurch W, Gardner W (2019) Complexity as integration: pastoral mobility and community building in ancient Mongolia. Soc Evol Hist 18(2):54–71

Childe G (1945) Directional changes in funerary practices during 50,000 years. Man 45:13–19

Conolly J (2017) Costly signalling in archaeology: origins, relevance, challenges and prospects. World Archaeol 49(4):435–445

Erasmus C (1965) Monument building: some field experiments. Southwest J Anthropol 21:277–301

Glatz C, Plourde AM (2011) Landscape monuments and political competition in late bronze age Anatolia: an investigation of costly signaling theory. Bull Am Sch Orient Res 361:33–66

Hageneuer S, Schmidt SC (2019) Monumentality by numbers. In: Buccellati F, Hageneuer S, van der Heyden S, Levenson F (eds) Size matters–understanding monumentality across ancient civilizations. Transcript Verlag, Bielefeld, pp 291–308

Hogue TS (2019) The eternal monument of the divine king: monumentality, reembodiment, and social formation in the decalogue. Ph.D. Dissertation, Near Eastern Languages and Cultures, UCLA

Hole F (2012) West Asian perspective on early monuments. In: Burger RL, Rosenswig RM (eds) Early new world monumentality. University Press of Florida, Gainsvill, pp 457–465

Honeychurch W (2015) Inner Asia and the spatial politics of empire: archaeology, mobility, and culture contact. Springer Publications, New York

Honeychurch W, Wright J, Amartuvshin CH (2009) Re-writing monumental landscapes as inner Asian political process. In: Hanks B, Linduff K (eds) Social complexity in prehistoric eurasia: monuments, metals, and mobility. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 330–357

Huang R, Needham J (1974) The nature of Chinese society: a technical. Interpretation. East and West 24(3–4):381–401

Jing A (1982) Guanyu Hulunbeie’r gu bianhao de shidai (On the Dating of the Hulunbeie’r Ancient Border Marking). Shehui kexue zhanxian 1:193–199

Jing A (2015) A history of the Great Wall of China. SCPG, New York

Jing A, Miao T (2008) Liao Jin bianhao yu changcheng (The Great Wall and Border Marker of the Liao and Jin). Dongbei Shidi 6:18–31

Lattimore O (1937) Origins of the Great Wall of China: a frontier concept in theory and practice. Geogr Rev 27(4):529–549

Levenson F (2019) Monuments and monumentality–different perspectives. In: Buccellati F, Hageneuer S, van der Heyden S, Levenson F (eds) Size matters–understanding monumentality across ancient civilizations. Transcript Verlag, Bielefeld, pp 17–40

Li Z (1931) The travels of an alchemist: the journey of the Taoist Ch’ang-Ch’un from China to Hindukush at the Summons of Chingiz Khan. G. Routledge & Sons, London, (Trans. Waley A)

Lin H (2011) Perceptions of liao urban landscapes: political practices and nomadic empires. Archaeol Dialog 18(2):223–243

Lunkov AV, Kharinskii V, Kradin NN, Kovychev EV (2011) The frontier fortification of the liao empire in eastern Transbaikalia. Silk Road 9:104–121

Ma Y (2013) Jin jiehao beixian’ zhi yiyi (Disagreement with the definition ‘the Northern Line of the Jin Boarder Mote’). Chinese Great Wall Museum J 37–43

McLuhan M (1964) Understanding media: the extensions of man. McGraw-Hill, New York

Neiman FD (1997) Conspicuous consumption as wasteful advertising: a darwinian perspective on spatial patterns in classic maya terminal monument dates. Archeol Papers Am Anthropol Assoc 7:267–290

Neimenggu ZWKY (2013) Neimenggu ziahiqu wenwu kaogu yanjiusuo 2012 Neimenggu ziahiqu wenwu kaogu yanjiusuo kaogu faxian zongshu. Caoyuan wenwu (Summary of Archaeological Findings by the Institute of Archaeology and Cultural Relics of Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region during 2012). Caoyuan Wenwu 1:1–9

Osborne JF (2014a) Monuments and monumentality. In: Osborne JF (ed) Approaching monumentality in archaeology. IEMA Proceedings. State University of New York Press, Albany. pp 1–19

Osborne JF (ed) (2014b) Approaching monumentality in archaeology, IEMA Proceedings. State University of New York Press, Albany

Ping Y (2008) Jin Changcheng de kaogu faxian yu yanjiu (Archaeological Research of the Jin Great Wall). In: Sun Wenzheng, Wang Yongcheng (eds) Jin Changcheng yanjiu lunji (Collected Research Papers on the Jin Wall), Vol. 2. Wenshi, Jilin. pp 88–166

Pines Y (2018) The earliest ‘Great Wall’? long wall of Qi revisited. J Am Oriental Soc 138(4):743–762

Shelach-Lavi G (2015) The archaeology of ancient China: from prehistory to the Han Dynasty. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Shelach G, Raphael K, Jaffe Y (2011) Sanzuodian: the structure, function and social significance of the earliest stone fortified sites in China. Antiquity. 85:11–26

Shelach-Lavi G, Wachtel I, Golan D, Batzorig O, Chunag A, Ellenblum R, Honeychurch W (2020) Medieval long-wall construction on the Mongolian Steppe during the eleventh to thirteenth centuries AD. Antiquity. 94(375):724–741. https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2020.51

Shen K, Crossley JN, Lun AW-C (1999) The nine chapters on mathematical arts. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Smith A (2003) The political landscape: constellations of authority in early complex polities. University of California Press, Berkeley

Spence M (1973) Job market signaling. Quart J Econ 87:355–374

Trigger BG (1990) Monumental architecture: a thermodynamic explanation of symbolic behavior. World Archaeol 22(2):119–132

Waldron A (1990) The Great Wall of China: from history to myth. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Wang G (1921) Jin jie haokao (The Border Trench of Jin). Zhonghua shuju, Beijing

Wright J (2017) The honest labour of stone mounds: monuments of bronze and iron age Mongolia as costly signals. World Archaeol 49(4):547–567

Wu H (1996) Monumentality in early Chinese art and architecture. Stanford University Press, Stanford

Yuan Z (1983) Cong Qinshihuang ling de kaogu ziliao kan Qin wangchao de yaoyi (Analyzing the Corvee System of the Qin Dynasty based on Archaeological Data from the Tomb of Qin Shihuang). Zhongguo nongming zhanzheng shi yanjiu jiekan 3:43–55

Zahavi A, Zahavi A (1997) The handicap principle: a missing piece of Darwin’s puzzle. Oxford University Press, Oxford, New York

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by research funds provided by the Louis Frieberg Chair of East Asian Studies, and by the Ring Family Foundation for Atmospheric and Global Studies, both at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Field equipment and U.S. participation were made possible with funding from the National Endowment for the Humanities (Grant RZ-249831-16). We greatly appreciate the generous support provided by the Mongolian Institute of Archeology and thank the local people of Dornod province for their assistance and kind hospitality. We are especially grateful for the Mandel Scholion Interdisciplinary Research Center in Humanities and Jewish Studies at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, for their kind support of this publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shelach-Lavi, G., Honeychurch, W. & Chunag, A. Does extra-large equal extra-ordinary? The ‘Wall of Chinggis Khan’ from a multidimensional perspective. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 7, 22 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-020-0524-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-020-0524-2