Abstract

This paper employs critical discourse analysis (CDA) to analyse the representation of political social actors in media coverage of the Gaza war of 2008–2009. The paper examines texts of systematically chosen news stories from four international newspapers: ‘The Guardian, The Times London, The New York Times and The Washington Post’. The findings show substantial similarities in representation patterns among the four newspapers. More specifically, the selected newspapers foreground Israeli agency in achieving a ceasefire, whereby Israeli actors are predominantly assigned activated roles. By contrast, the four newspapers foreground Palestinian agency in refusing ceasefire through assigning activated roles. The findings of this study suggest that news reports on the Gaza war of 2008–2009 are influenced by the political orientations of the newspapers and also their liberal and conservative ideological stances. Overall, the most represented actors are Israeli governmental officials, whereas Palestinian actors are Hamas members. This representation draws an overall image that the war is being directed against Hamas.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

This paper provides a critical discourse analysis (henceforth CDA) of US and UK press coverage of the Gaza War of 2008–2009, which took place during the days between December 27, 2008 and January 18, 2009. This paper seeks to delineate in particular the discursive practices and linguistic features that are responsible for drawing a specific representation of the social actors. My motivation for conducting the current article includes various dimensions:

CDA has an overtly political agenda (Kress, 1990) which is very relevant to examine war coverage. CDA aims ultimately to make a change of 'the existing social reality in which discourse is related in particular ways to other social elements such as power relations, ideologies, economic and political strategies and policies' (Fairclough, 2014). This is one of the ultimate goals of this paper in analysing war reporting in the international press. The paper does not aim to blame a part over the other rather than it aims to show factors influencing the reporting of the Gaza War of 2008–2009.

Among CDA frameworks, the paper employs the socio-semantic inventory proposed by van Leeuwen (1996). This framework provides principles and accurate representation choices. KhosraviNik (2008, p 14) suggests that the socio-semantic inventory 'certainly lays the ground for an explanatory framework for CDA studies' (see also KhosraviNik, 2010). The inventory examines language in the context that “reveals specific attitudes, ideologies and worldviews which are encoded through language” (Adampa, 1999, p 3).

The Gaza war is considered a turning point in changing attitudes towards Israel and more involvement of international community in the Israeli–Palestinian conflict. Across the years of conflict, both the Israelis and the Palestinians have accused the Western media (mainly the American and British press) of bias against their own side and issue. Israelis claimed the coverage by Western media was biased because it focused on the killing of Palestinian civilians. Palestinians and their supporters consider the media portrayal of Palestinian attacks as starting a cycle of violence that gets an Israeli response (see Cordesman and Moravitz, 2005, p 390).

To the best of my knowledge, a few CDA studies have examined the media coverage of the Israeli–Palestinian conflict. However, this paper is different from other CDA or media studies on Israeli–Palestinian conflict in several points: (1) This study examines not only the linguistic features, discursive strategies and representational categories, but also the specific images and patterns of representations in media coverage (see Kandil, 2009; Shreim, 2012; Kaposi, 2014; Almeida, 2011). (2) Most studies have been conducted within either an American or a British media context (see Ozohu-Suleiman, 2014). This paper lies in its CDA examination of representing social actors in both American and British contexts. (3) This paper focuses on the international level (US vs. UK) of newspapers by employing socio-semantic inventory (see section Socio-semantic inventory: main concept and representational categories).

In exclusively investigating the Gaza war of 2008–2009, this paper aims to contribute to critical understanding and discourse analysis of the international press on Middle East wars and mainly the case of Gaza in the American and British newspapers. More specifically this paper aims to

-

1.

Find the differing representations of social actors and processes by identifying the representational processes used by the US and UK newspapers in their reporting of the Gaza war of 2008–2009.

-

2.

Unveil ideologies underlying the different practices in the representation of social actors and examine their reflections on the image of Israeli and Palestinian actors in the international press.

To achieve the above-mentioned objectives, the paper employs CDA as the study’s main approach as we can see in the following section.

CDA: conception and principles

CDA is a form of discourse analysis that is a broad and complex interdisciplinary field (Fairclough and Wodak, 1997; Wodak and Meyer 2001) with different theories, methodologies and research issues (Jørgensen and Phillips, 2002; Weiss and Wodak, 2003; Blommaert, 2005). It is 'a perspective on critical scholarship: a theory and a method of analysing the way that individuals and institutions use language' (Richardson, 2007, p 1–2). This shows that CDA has taken as its subject the study of the intertwined links between language use and social power. From such a perspective and in line with Richardson’s view of CDA in his book 'Analysis of newspapers', this paper points out that

Critical discourse analysts offer interpretations [and explanation] of the meanings of texts rather than just quantifying textual features and deriving meaning from this; situate what is written or said in the context in which it occurs, rather than just summarizing patterns or regularities in texts; and argue that textual meaning is constructed through an interaction between producer, text and consumer rather than simply being read off the page by all readers in exactly the same way (2007, p 15).

This constructivist approach of CDA asserts that meaning in discourse hides in or lies behind the words (the language). Richardson writes, 'CDA argues that textual meaning is constructed through an interaction between producer, text and consumer that rather than simply being read off the page by all readers in exactly the same way' (2007, p 15). Such a view shows that language is constructive, and thus it draws a discourse that shapes images and representation of social actors.

In this respect, to extract the actual meaning, we should be critical. That is, there should give more explanations and state reasons why the discourse is like this rather than just interpretations of texts or just identifying and counting features and types of discourse. KhosraviNik (2008, p 5) points out that 'a critical analysis would consider a systematic description of a discourse'. This includes description of the characteristics of the language in a text as merely the first though essential level of analysis and would call for going beyond this and explaining why and with what consequences the producers of a text have made specific linguistic choices (or have avoided doing so) among several other options that a given language may provide. Critically, the analysis targets the discursive practices constructed and presented in a group of processes of news production and consumption and the larger context that constructs the discourse(s). This means that we should ask that why is the discourse constructed or the representation of social actors like this (see Fairclough, 2014). In this light, my critical analysis of war reporting looks for absences and presences in the sampled data; the sample is chosen systematically and the analysis points to a context of the findings by referring to ideological and political factors behind the war coverage of the Gaza War of 2008–2009 (see section Factors influencing War reporting of the Gaza War of 2008–2009).

From a critical scholarship perspective, CDA essentially stems out from the premise that language is a social and practical construct which is characterised by a symbiotic relationship with society. In this context, Fairclough and Wodak (1997, p 277–280) suggest principles for CDA summarised briefly in eight points (see also Titscher et al., 2000, p 146):

-

1.

CDA addresses social problems.

-

2.

Power relations are discursive.

-

3.

Discourse constitutes society and culture.

-

4.

Discourse does ideological work.

-

5.

Discourse is historical.

-

6.

The link between text and society is mediated.

-

7.

Discourse analysis is interpretive and explanatory.

-

8.

Discourse is a form of social action.

Within these principles and aims, CDA is used to examine the representation of social actors (Israeli and Palestinian) in the discourse of four influential and international US and UK newspapers in the coverage of the Gaza war of 2008–2009 (see section Data collection and sampling: the selected newspapers). It highlights the linguistic features and discourse practices motivated by media producers in their representation of the social actors. Namely, how these manipulate the cognition and knowledge of the target audiences when reporting war events. CDA then examines ideological stances or implications in the press discourses on the Gaza war of 2008–2009. Accordingly, some power relations are sustained ultimately in the interplay between media, war and language use as explained in the following section.

Interplay of discourse, media, representation and ideology

Discourse in media consists of both texts (news stories relatively), and the processes to build and produce the texts. Discourse in media obviously reflects ideological interests and stances of those in powerful positions, i.e., the elite, politicians, journalists, etc. (Fowler, 1991; Fairclough, 1989, 2001, 2003; Van Dijk, 1997, 1998a, 1998b; Richardson, 2007). In this context, Fairclough (2001, p 40) considers media discourse as a 'one-sided' event that has a sharp discerned division between producers and interpreters. That is, one crucial function of media discourse is to communicate between two domains: the public and the private concerning the temporal setting of media properties. Media bring news about various issues, e.g., political, war, criminal, economic or social to people through TVs, radios, newspapers and recently through social media platforms, e.g., Facebook and Twitter. In this paper, I focus on how the selected newspapers cover the events of the Gaza war of 2008–2009 and bring them to their readers. Within these texts, discourse is interlinked with and draws a representation of social actors.

Representation depends on specific perspectives from which social actors are constructed. Wenden (2005, p 90) explains that representation refers to the language used in a text or talk to assign meanings to groups and their social practices, to events, and to social and ecological conditions and objects in discourse analysis (e.g., Fairclough, 1989, 1995a, b). This paper refers representation to the process of meaning production through combination of texts. Accordingly, meaning is constructed by linguistic representation in news media. Representation of social actors relates them to specific behaviours and attitudes, e.g., making violence, making efforts to achieve a ceasefire, firing rockets, etc., as we shall see in the analytical section 7. These particular representations of individuals or groups in media are linked to certain ideologies (see Chiluwa, 2011, p 197).

One can posit that ideology underlines any form of the linguistic expression in a text, a sentence or paragraph. Androutsopoulos (2010, p 182) points out that researchers from sociolinguistics, language ideology and media discourse all 'agree on the potential of discourse in mainstream media to shape the language ideologies of their audience, that is, their belief, or feelings about language as used in their social world'. He further suggests that 'language ideologies are not neutral or objective, but serve individuals or group-specific interests, that is, they are always formulated from a particular social perspective and have particular referents and targets' (2010, p 183). In this regard, this paper is based on the premise that linguistic choices in texts carry ideological meaning(s). Hence, we can expect reporters/journalists to frame, legitimise, or validate actions and opinions in covering events (see Wenden, 2005, p 93). For example, such an ideological process may control the general point of view of the Gaza war of 2008–2009.

The interplay among discourse, media, representation and ideology in war coverage makes them components in the process of building news especially when war is considered as an international crisis and is changed from inter-state to intra-state or vice versa (see Amer, 2016 and Connelly and Welch, 2005, p 15). In the next sections 4 and 5, I discuss the concept of war reporting in international news.

War reporting: conception

Reporting wars in media is an essential resource for journalism and readers. Considering news as a genre, and in line with Richardson’s (2007) view that news is argumentative genre, understanding the nature of war is essential to understand the way wars are reported, represented, covered, and analysed by different media outlets. This paper considers war reporting as

A multi-function-task operated/executed by journalists in a war time to cover war events using language that conveys patterns of representation (discourse) on the war actors to either local or international audience(s) (Amer, 2016, p 42).

Simply, this multi-function task implies reporting and covering the military actions. Doing such a task requires the journalists covering war(s) to be prepared to gather information in order to keep the local and international audiences informed of the war events in an objective way of reporting. The task is multi-functional in terms of the information they provide on the war events. The journalists covering war events not only aim to persuade and convince their audiences of their description and interpretation of the war events/actions as being the rational and appropriate ones, but also they convey specific representations of the actors and processes of the war.

International news flow: US and UK media

‘International news’ is a vague term and it is problematic in building a theory to analyse conflicts and wars in international media. International news in this article means mainly the news published by newspapers that have a wide readership. In addition, this news is also foreign news to the newspapers’ national audiences and is produced (mostly) by foreign journalistsFootnote 1 who report news from outside their countries. 'International reporting can be used as a synonym of foreign reporting' (Oganjanyan, 2012, p 8). For this vagueness, this paper focuses mainly on the American and British press as international press. They are both published in the English language, which represents the most widely used language all over the world. This fact represents a reason why the American and British press are international.

In this section, I show some similarities and differences between the US and UK media in general and their involvement in the Israeli–Palestinian conflict. Both media give their audiences in the USA and the UK a wide range of views, coverage, reports and representations of the same war events and actors. However, claiming of similarities in attitudes towards international crises, e.g., Gaza war in the US and UK media should be, I think, cautiously made because the US and the UK have differences in the economic, cultural and political systems that assumingly lead to differences in the way that the press in the two countries cover events around the world. Below, I discuss some of the similarities and differences between the US and UK press.

The US and the UK have democratic governmental systems that can provide good backgrounds and contexts for comparative study in media. 'The press in each nation is greatly admired for its tenacity regarding the ideals of freedom of the press and for embracing its role as the fourth estate' (Dardis, 2006, p 411, see also Hallin and Mancini (2004, p 87).

The US and the UK are different in some points. First, both countries have different (cultures and political) environments that influence how citizens deal with and view various issues related to society and events around the world. In consequence, this difference leads to various notions of media professionalism and delineates the basic philosophies of the role of media in each society, and their media dealing with and covering international issues. Second, the difference is in the distribution and size of readership. Tunstall (1996, p 7–11) explains that the British press mostly is based in London; which is the home of the largest national newspapers in Western Europe. UK press enjoys readership very much along social class lines. It is known internationally for its tabloid newspapers (see also Williams, 2010, p 231–233). In the US, the press is 'predominantly regional and, with a few exceptions, contains regional monopolies which are not subject to the same competitive pressures' (Goddard, Robinson and Parry, 2008, p 12).

Both the US and the UK press have a direct and/or an indirect-national connection to events in the on-going Arab–Israeli conflict. The main concern of this paper is how the US and UK press covered the Gaza war of 2008–2009. Khoury-Machool (2009, p 6) claims that 'media coverage of the conflict remains a continual site of struggle, with both parties accusing the media of bias toward the opposition'.

Kamalipour (1995, p 38–40) explains some reasons contributing to the Palestinian image in the US media. (1) The disappearance of the Palestinians and Palestine from American coverage because of the birth of Israel as a state in 1948 as well. (2) The special relations between US and Israel served to hide the Palestinian voice in the American media. In contrast to the Palestinian image in US media, the Israelis have a different image. El-Bilawi (2011, p 133) explains, Israel 'has already poured hundreds of millions of dollars into funding for producing information marketed to the outside world; in particular, they have used the media in the United States effectively over a long period of time'.

UK media has paid particular interests to the Israeli–Palestinian conflict. It can be argued that the UK is responsible for the catastrophe that happened to the Palestinians in 1948 which has still affected the whole situation during the on-going Israeli–Palestinian conflict (see Philo and Berry, 2004 and 2011). British media represent the Palestinians in a negative image in their conflict with the Israelis (see a study by Philo and Berry, 2004). The study suggests that television coverage of the Israel/Palestinian conflict confused viewers and was one sided, mostly featuring the views of the Israeli government. According to Barkho (2008, p 281), BBC journalists and editors follow a strict guideline of facts and terminology recommended by the BBC governor’s independent panel report on the impartiality of BBC’s coverage of the conflict. This report includes the BBC’s College of Journalism’s online-module—Israel and the Palestinians—specially designed for journalists who intend to cover the region.

This short synopsis of differences and involvement of the American and British press in the Israeli–Palestinian conflict leads to possible assumptions that both the US and UK media provide different coverage of events around the world. Also, the US and UK press give an interest and prominence to the international political news such as wars and conflicts in the Middle East. The question remains how the US and UK media cover the Gaza war of 2008–09. This is the core point in this article.

Methodological analytical framework

Within a CDA framework, this paper applies Van Leeuwen’s (1996) socio–semantic inventory to analyse the body text of the sampled news stories.

Research questions

The news from the Gaza Strip is considered to be foreign and international for the selected newspapers as we have already seen in the previous section. In this regard, this study aims to answer the following broad question:

RQ1) How do the US and UK newspapers discursively represent the social actors in reporting the Gaza war of 2008–2009?

The study intends to answer this broad question by providing answers to the following secondary questions:

RQ2) How are the representational categories used to construct the social actors in news stories and editorials?

RQ3) What conclusions can be drawn from the representation of the social actors?

For answering the research questions, the study applies certain procedures to collect and analyse the sample data.

Data collection and sampling: the selected newspapers

The paper chooses to examine two British newspapers (The Guardian, The Times London) and two American newspapers (The New York Tim and The Washington Post). The selection is based on the large circulation in their countries and their popularity around the world, and this makes them international. According to Audit Bureau of Circulations (UK)Footnote 2, April 2011, the daily circulation of 'The Times' (Lodon) is 449,809 copies and 'The Guardian' is 263,907 copies. Alliance for Audited MediaFootnote 3 shows that the circulation of 'The New York Times' is 1,865,318 copies and 'The Washington Post' has 474,767 copies. The selected newspapers are also chosen for their political orientation and ideological stances, i.e., liberal and conservative. They are available at the research engines: LexisNexisFootnote 4 and Microfilm. The four selected newspapers are considered elite and prominent publications on the international level.

Representative-purposive systematic: news stories

I collected the data from LexisNexis and Microfilm enginesFootnote 5 For all materials from LexisNexis and Microfilm, I extracted all the materials related to the Israeli war on Gaza in 2008–2009. The paper follows a purposive sample that reflects and supports the purpose of examining and analysing the data. Seale (2012, p 237) explains that when using purposive sampling, items are 'selected on the basis of having a significant relation to the research topic'. Purposive sample seeks to be 'reflective (if not strictly representative) of the population'. The sample arguably represents the texts of the four selected newspapers from which it is chosen systematically. The sample consists of hard news presented in news stories. From these news stories, I selected 40 news texts based on systematic criteria.

-

1.

News stories are publishedFootnote 6 on homepages, news pages and international pages of each newspaper. These pages are the relevant pages to the news stories published on wars, conflicts or international issues, and they are related to the field of the study. That is, the choice excludes the Op-Ed and commentary articles. Apart from the headlines, these types of news articles are simply not written by war reporters/correspondents or editors in chief.

-

2.

News stories cover the Gaza war of 2008–2009, and excluding the news which just mentions war without focusing on it.

-

3.

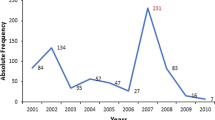

The number of words of the report, and this is done by calculating the average of words of news stories according to each newspaper because the word numbers of news stories are different in the newspapers. The calculation is done only on the news stories that match the previous two points of the criteria. This helps in the selection of news stories that are (mostly) equal in length in each newspaper (Table 1

Table 1 Number of words of news stories and their average in the selected newspapers ).

-

4.

Based on these criteria, ten news stories are selected from each newspaper that approximate the average. That is, five news stories with more words than the average, and five news stories with less words than the average are chosen in consecutive order. This means (40) news stories are selected systematically in purpose to represent all data published on the Gaza war in the specified period. These criteria are used only to choose the representative sample, and specify the news stories.

Socio-semantic inventory: main concept and representational categories

The methodological framework utilises a socio-semantic inventory systematically to show how the social actors are represented in the texts. As a CDA approach, Van Leeuwen’s (1996) model analyses 'how social and political inequalities are manifested in and reproduced through discourse' (Wooffitt, 2005, p 137). It is presented as a 'pan-semiotic' system for doing critical analysis of verbal–visual media texts (Van Leeuwen, 1996, p 34). The inventory has ten categories. However, to examine linguistic features and discursive practices implied in the body texts of the sample news stories, the analysis of representation of social actors in this paper employs six categories as we can see below. I choose these representation categories (see also Farrelly, 2015) because they are the most suitable, relevant and applicable processes to examine how the social actors are represented.

1. Inclusion and/or exclusion. Exclusion has two subcategories: (1) 'radical' (total) Radical exclusion means total/complete suppression, i.e., there is no trace or reference to the social actors, and their actions/activities anywhere in the text. (2) 'Less radical' (partial) means backgrounding of social actors. Social actors are mentioned not immediately in the activity but somewhere in the text.

2. Role allocation distinguishes between activated and passivated roles allocated with social actors. Activated roles mean representing the social actors as active and dynamic in the activities. Passivated roles mean social actors are presented as undergoing the activity (object) or at receiving end of the activity in the text.

3. Genericisation and specification indicate how the authors of texts use either generic reference or specific reference to the social actors. Specific reference refers to 'identifiable' individuals (Van Leeuwen, 1996, p 46). This means they are real people living in a real world.

4. Individualisation and assimilation are strict parts of specification of social actors. This means in specification, the social actors are either specified as individuals or as a group of participants. However, in this category the main emphasis is on the social actors as single entities.

Assimilation specifies social actors as a group of participants. According to Van Leeuwen (1996), assimilation can be classified as aggregation or as collectivisation. Aggregation quantifies groups of participants, treating them as statistics.

Collectivisation does not have specific number of actors, i.e., there is no statistics of social actors.

5. Nomination and Categorisation refer to social actors in terms of their unique identity as being nominated or as functionalised. In the socio-semantic inventory, nomination is a way of addressing people and generally realised by proper nouns.

6. Functionalisation and Identification are part of categorisation of social actors. Functionalisation refers to activities, occupations and roles of social actors. Identification refers to prominent features. It refers to what the social actors are referred to, i.e., how they appear rather than their activities.

Socio-semantic representation of political social actors

This section examines the question of how representational categories construct the social actors in four newspapers; two American and two British by applying six of Van Leeuwen’s (1996) socio-semantic categories to the texts. Since the space is limited, I focus only on political actors in this paper. Israeli and Palestinian political actors (PPA) are excluded in four themes as shown in Table (2): ceasefire, internal affairs, ground invasion and the targeting of Hamas.

This table suggests that the selected newspapers use different processes in excluding Israeli and Palestinian political actors in ceasefire and similar processes to exclude them by backgrounding them in internal affairs. Moreover, Israeli political actors (IPA) are backgrounded in ground invasion, and PPA are suppressed in targeting Hamas. Because of the limited space, I have selected only ceasefire for detailed examination. It is the most suitable theme and relevant for roles of political actors mainly in war time, where we can see political and diplomatic efforts. Also, it is the most frequent theme in three newspapers (GU, TL and WP). Israeli politicians are represented as making efforts to achieve a ceasefire, whereas Palestinian politicians are represented as reluctant to agree to ceasefire. For example,

-

1.

Israel is expected to announce a unilateral ceasefire tonight that will end its 3-week war in Gaza. GA-TL-17-JAN-01

-

2.

Hamas is prepared to commit to a year and then consider renewing it. GA-GU-17-JAN-02

-

3.

Hamas was excluded from the talks because it is labelled a terrorist group by the United States. GA-WP-03-JAN-01

IPA are presented in 'Israel' while PPA are presented in 'Hamas'. In examining the process of exclusion, IPA and PPA are represented similarly in the clause structure in passive forms. Their attitudes and efforts towards a ceasefire are opposed. In example 1, there is no clear reference in the text to the social actors who expect Israel to announce a ceasefire as evident in 'Israel is expected to announce'. In this case, social actors could be Israelis themselves, Palestinians or the international community. But, later in the text, the author mentions that the announcement relies on the agreement of the Israeli security cabinet. This announcement is intended to stop the war in Gaza.

In the treatment of Palestinians, GU in example 2 represents 'Hamas' as hesitant in agreeing to a ceasefire. The verb 'consider' does not show certainty to renew or stop the ceasefire as it was clear in the phrase 'Hamas is prepared to commit to a year'. In this way, GU uses passive agent deletion by which there is no trace for those social actors who prepared Hamas to commit a ceasefire. In a previous part in the text, the author writes that Hamas had talks with Egyptian officials, and later in the text he follows 'Israel wants it to be indefinite'. In this case, it is not clear who made Hamas commit to a ceasefire: are they Israelis, Palestinian authority officials, Hamas itself, or even the Egyptians who mediate the agreement of ceasefire?

WP shows Hamas was negatively constructed as a terrorist group that does not seek ceasefire. In example 3, Hamas is being suppressed, i.e., excluded from ceasefire negotiations without reference to who excluded it. In this case, it could be Israel, the USA, the EU, Egypt or even the Palestinian Authority. The author’s justification of this exclusion is the labelling of Hamas as a terrorist organisation by the United States. Also, it links targeting Hamas to the United States’ War on Terror. This is clearly shown multiple times in the text. 'Bush has generally supported Israeli military actions during his eight years in office, while strongly condemning Hamas, the Lebanese Hezbollah movement and other anti-Israel groups that are considered terrorist organizations by the US government'.

The comparison suggests that Israelis are excluded when they declare a unilateral ceasefire. This declaration is followed by efforts leading to a ceasefire. These efforts foreground the Israeli agency and its commitment to achieve a ceasefire. In the examples above, the representation calls and evokes negative and irrational judgements towards Hamas (see Richardson, 2007, p 205), and influences reporting the Gaza war of 2008–2009 (Amer, 2016). The construction by exclusion incorporates a negative sentiment towards Hamas over a positive image of Israelis. The analysis focused on exclusion of social actors. Now, I turn to examine the inclusion of Israeli and Palestinian political actors by firstly focusing on the themes associated with them (see the following Table 3).

Table (3) shows IPA are included in four dominant themes and PPA are included in two dominant themes across the newspapers (see the numbered themes). To examine how the political actors are included, this section starts by looking at the roles allocated to the political actors. My intention is to focus only on the theme of ceasefire for the same reasons mentioned above in examining the exclusion of social actors. The following clauses exemplify how IPA are included in ceasefire as they are activated only in GU, TL and WP.

-

4.

Israel’s envoy to Cairo returned to Jerusalem last night with details of Hamas’s position. GA-GU-16-JAN-02

-

5.

Israel welcomed an Egyptian proposal for a truce with Hamas, the Islamists rulers of Gaza, yet its security Cabinet voted to push ahead with its ground offensive while it worked out the details with international envoys. GA-TL-08-JAN-02

-

6.

An Israeli Defense Ministry official, Amos Gilad, was negotiating with the Egyptians by phone Monday and was expected to travel to Cairo later in the week. GA-WP-13-JAN-01

GU, TL and WP activate Israeli roles and efforts to achieve a ceasefire agreement in Egypt. This can be shown in the underlined verbs: returned, welcomed and was negotiating. These efforts come into contexts in the full texts, e.g., An Israeli foreign minister travelling to USA to sign an agreement with US foreign minister (GU), reference to Israeli security concerns, e.g., its security Cabinet voted to push ahead with its ground offensive (TL), and progress in the ceasefire negotiations e.g., the moves came as negotiators in Cairo sought to reach a cease-fire agreement, hoping to put a halt to violence (WP).

In these examples, it is clear that TL and WP report Israeli demands for a ceasefire presented in the Israeli condition for Hamas to lay its weapons down. Generally, GU, TL and WP foreground Israelis as a dynamic force in making efforts to achieve a ceasefire with Palestinians whose attitudes towards ceasefire are opposite. They reject or put conditions on ceasefire.

-

7.

The Islamist group also wants Gaza’s crossings into Israel reopened after three years of economic blockade. GA-GU-17-JAN-02

-

8.

Khaled Meshal, the exiled 'Hamas' leader in Damascus, rejected the ceasefire demands yesterday, insisting that Israel should withdraw its troops and immediately open Gaza’s borders and lift the blockade it imposed after Hamas seized power there in 2007. GA-TL-17-JAN-01

-

9.

Hamas officials, who have been involved separately in negotiations with Egypt, reacted coolly to the cease-fire plan. GA-WP-08-JAN-02

-

10.

The Palestinian president, Mahmoud Abbas, whose Fatah Party opposes Hamas, was in Cairo pressing a call for a cease-fire, and he discussed with President Hosni Mubarak of Egypt the idea of international troops along the Gaza-Egypt border. GA-NYT-11-JAN-04

Hamas’ stance (discourse) towards the ceasefire can be shown in the underlined verbs, e.g., wants, rejected, reacted and was […] pressing. These verbs come in the context of demands to open the crossings in the Gaza Strip, and to end the Israeli blockade of Gaza (GU), an immediate Israeli withdrawal, the end of Israel’s blockade of Gaza and the opening of all crossings (TL), and cool reactions to ceasefire efforts by international community. This is in contrast to NYT which focuses on the President of the Palestinian Authority by allocating an activated role in discussing possibilities of the ceasefire with the Egyptian president, Mubarak. This pattern of representation contrasts with the roles allocated to Israeli politicians, as they make efforts to bring about a ceasefire. In these examples, Hamas is represented as dynamic in rejecting a ceasefire and placing conditions and demands to agree on ceasefire terms, while the President of the Palestinian National Authority makes great efforts to agree to, and puts pressure on Hamas to accept, the Egyptian ceasefire plan. This conceals Hamas’ efforts to negotiate a ceasefire (see section Causality aspects and agency: Israeli response vs. Hamas causality).

In examining how social actors are included, examination of genericisation and specification is also essential to see how the newspapers refer to, and represent, Israeli and Palestinian political actors in their efforts to achieve a ceasefire. IPA are genericised by the use of mass nouns presented mainly as 'Israel' (examples 11–13).

-

11.

Israel wants to ensure that an internationally brokered ceasefire (GA-GU-16-JAN-02)

-

12.

Israel welcomed an Egyptian proposal (see Ex5Footnote 7, GA-TL-08-JAN-02)

-

13.

Israel brushed aside…..to broker a cease-fire in the Gaza Strip (GA-WP-06-JAN-01)

These genericisation processes identify IPA as provenance presented in 'Israel' in GU, TL and WP. Furthermore, GU and WP genericise IPA by plurals without articles, e.g., Israeli governmental officials (example 14) and negotiators (example 15).

-

14.

some senior Israeli officials were optimistic (GA-GU-17-JAN-02)

-

15.

The moves came as [Israeli] negotiators in (GA-WP-13-JAN-01).

In these genericisations, IPA are functionalised by adding suffixes to verbs in TL and WP as evident in the word negotiators (see examples 15 and 21). These practices clarify the Israeli efforts on the national level (Israel) and on individual level (political actors). Behind this apparent Israeli concession of offering and making ceasefire, Palestinians are represented as passive recipients presented mainly in Hamas.

PPA are genericised by mass nouns and plurals without articles. GU, TL and WP genericise PPA in mass nouns mainly as 'Hamas' when they refer to Hamas’ demands or the decision to reject the ceasefire or being excluded from the ceasefire talks. For example,

-

16.

Hamas had hoped the ceasefire would lead to the lifting of the blockade (GA-GU-27-DEC-01)

-

17.

Hamas opposes the deployment of an international force on that border and particularly abhors an Egyptian proposal (GA-TL-14-JAN-02)

-

18.

Hamas was excluded from the talks (Ex3, GA-WP-03-JAN-01)

These genericisations identify PPA by provenance of Hamas in GU, TL and WP. NYT and WP genericise PPA in plural forms as Hamas actors when they refer to Hamas involvement in the negotiation process itself, in Cairo, For example,

-

19.

Hamas representatives were also there, but the plan, also urged by the French, seemed to be losing steam (GA-NYT-11-JAN-04)

-

20.

Hamas officials…. reacted coolly (Ex9, GA-WP-08-JAN-02).

These patterns of representation exclude reference to members of the Palestinian Authority and focus more on Hamas’ officials. PPA are also categorised by functionalisation by adding suffixes to a verb in TL as evident in the word negotiator in the following example.

-

21.

Five Hamas negotiators from Gaza and Damascus have spent the past few days in Cairo (GA-TL-14-JAN-02).

The analysis of the genericisation process discovers a similarity between genericising Israeli and Palestinian political actors by mass nouns and by plural forms without articles in GU, TL and WP. The examination of the specifications of political actors reveals that they are specified as individuals and as assimilation, i.e., groups (see section Socio-semantic inventory: main concept and representational categories). As individuals, Israeli politicians are represented as governmental actors in GU, TL and WP. Those actors are presented as taking genuine steps to achieve a ceasefire. For example,

-

22.

the Israeli foreign minister, Tzipi Livni, was due to fly to Washington to finalise an accord (GA-GU-16-JAN-02)

-

23.

Tzipi Livni, […] signed an agreement with Condoleezza Rice (GA-TL-17-JAN-01)

-

24.

Olmert did not say when Israeli troops would withdraw from Gaza [….] raising the possibility that the cease-fire could be short-lived (GA-WP-18-JAN-01).

In this pattern, IPA are nominated in a semi-formal way in GU and TL, e.g., Tzipi Livni, while they are nominated formally in WP, e.g., Olmert. These nominations of Israeli official leaders illustrate the newspapers’ insistence that those actors are determined to bring about a ceasefire. These efforts are represented in assimilating IPA by aggregation in GU and TL. The authors refer to numbers of Israeli social actors using quantifiers, 'three' and 'two' in these clauses,

-

25.

the three have reportedly been in disagreement (GA-GU-16-JAN-02)

-

26.

two top Israeli negotiators spent a day in Cairo discussing how Egypt could stop weapons (GA-TL-17-JAN-01).

There is a substantial consistency in the syntactic position and semantic roles, PPA are specified as Hamas individuals in TL, NYT and WP when they reject a ceasefire (examples 27–29), and as individuals of the Palestinian Authority in NYT in making efforts to achieve a ceasefire (example 30).

-

27.

Khaled Meshal, the exiled Hamas leader in Damascus, rejected the ceasefire demands. (Ex8, GA-TL-17-JAN-01)

-

28.

Moussa Abu Marzouk, the exiled deputy to the Hamas political chief Khaled Meshal, told Al Jazeera television on Tuesday that while the organization had “serious reservations” about the Egyptian cease-fire plan, he believed that it might be accepted if changes were made. (GA-NYT-14-JAN-02)

-

29.

Ahmed Youssef, a Hamas spokesman in Gaza, said the group would not stop firing rockets into southern Israel until the Israeli military withdrew from the Palestinian territory and ended the economic blockade, which has left Gaza’s 1.5 million people dependent on smugglers and relief organizations for their basic needs. (GA-WP-08-JAN-02)

-

30.

The Palestinian president, Mahmoud Abbas […..] was in Cairo pressing a call for a cease-fire. (GA-NYT-11-JAN-04)

These specifications present similar nomination forms (semi-formal way) as evident in Khaled Meshal, Moussa Abu Marzouk, Ahmed Youssef and Mahmoud Abbas in TL, NYT and WP. Here we can see similarity in genericising and specifying the political actors mainly as Israel on one side and Hamas on the other side. By this finding, the newspapers arguably represent the Gaza war of 2008–09 as a war between Israel and Hamas (see section Overall picture: an Israeli War against Hamas).

IPA are included and excluded mostly as Israel, governmental and non-governmentalFootnote 8 actors, whereas PPA actors are included and excluded as Hamas or Hamas members. IPA are represented mainly as making efforts to achieve a ceasefire, whereas PPA mainly Hamas reject or impose demands to agree on a ceasefire. The choice of representation patterns risks generating an imbalance in war reporting and “has the potential of characterising people in different ways (Barkho and Richardson, 2010). This pattern represents Hamas as a threat to a ceasefire in the war, and thus, foregrounds their agency, i.e., responsibility in initiating the violence.

Overall the representation, the analysis shows a dominance of the Israeli perspective to have a ceasefire and stop Hamas’ rockets. This pattern arguably draws a negative impression (discourse) of Hamas and shows Hamas’ causality, e.g., refusing a ceasefire. The consistence in representing Israeli actors as Israel and Palestinian actors as Hamas presents the war to be against Hamas only (see section Overall picture: an Israeli War against Hamas). This might show indirectly or directly that the activities of the Israelis are to be viewed as an imperative national assignment responding and reacting to Hamas violence.

Conclusions

This section referred to the discourse(s) found in the analysis of linguistic and representational processes, rather than simply focusing on more general differences between the newspapers. Through CDA, I am able to highlight causality aspects and agency of the social actors, factors that influenced reporting of the Gaza war of 2008–2009 and a summary how the war was represented.

Causality aspects and agency: Israeli response vs. Hamas causality

This section dealt with realisations of agency in media discourse around the Gaza war of 2008–2009 referring to theoretical outlines and conceptions discussed in sections 2–5. The CDA of the four newspapers corroborates the definition of discourse as a practice (textual, discursive and social) for evaluating and justifying what is happening (see Amer, 2016; Fairclough, 1995a, b; Van Leeuwen, 2008). This subsection concerns the response and causality aspects of Israel and Hamas. The Israeli response is portrayed in benevolence in offering a ceasefire.

The four newspapers show substantial consistency in focusing on Israeli discourse regarding the ceasefire between Israel and Hamas. This discourse focuses on efforts such as declaring a ceasefire (examples 4–6). This pattern highlights Israelis’ efforts at ceasefire negotiations and shows a tendency among editors to produce a positive discourse, i.e., foregrounding the Israeli agency positively (compare Ackerman, 2001).

The linguistic features are substantially ideological in reproducing a general discourse that aligns with the Israeli message that they only target Hamas rather than all Palestinians because Hamas refuses the ceasefire and fires rockets into Israel (see examples 11 and 1). “The officially stated Israeli goal of Operation Cast LeadFootnote 9 was to diminish the security threat to residents of southern Israel by steeply reducing rocket fire from the Gaza Strip, weakening Hamas” (Zanotti et al., 2009, p7; see also Philo, 2012, p 155). This conveys positive attitudes towards Israel and possibly generates justifications for Israeli actions, which is evident from the fact that Hamas’ views on ceasefire are not represented in these texts. The causality aspects of Hamas are implied in Hamas’ refusal of a ceasefire. Hamas is portrayed as imposing conditions before they will agree with the ceasefire terms (see examples 7–9).

From this explanation, we can see that the selected newspapers produce shared perspectives and discourses that were similar yet unevenly realised, across the categories of socio–semantic inventory. The communication of news events cannot claim to be objective. The events and the ideas must be transmitted through media outlets, i.e., newspapers in this paper, with their own philosophies, attitudes and linguistic expressions. In all respects, the analysis of the representation of the Gaza war of 2008–2009 points to the conclusion that the war is being represented as a war against Hamas and not against the Palestinians and influenced by some factors as we can see in the following section.

Factors influencing War reporting of the Gaza War of 2008–2009

The more newsworthy an event is considered to be, the more likely it is to be selected for publication and to be presented prominently. I refer to two factors that influence reporting the Gaza war of 2008–2009 and reproducing the discourse or war reporting, as explained in the previous sections. This section explains 'why is discourse like this?' (Fairclough, 2014) in the US and UK selected newspapers (GU, TL, NYT, WP) as examples of the international press (see section Data collection and sampling: the selected newspapers).

Political orientation: alignment with foreign policy

This subsection focuses on the similarity in the newspapers’ representation of social actors in relation to the foreign policyFootnote 10 of the USA and UK on the Israeli–Palestinian conflict. For this similarity, there are different reasons such as the role of media, US public opinion supporting Israel, the location of Israel in the Middle East, and the Israeli lobby in the USA (see also Hansen, 2008; Mearsheimer and Walt, 2006; Slater, 2007). The exploration of all these reasons in detail is behind the scope of this study. I will merely suggest that there are similar lines between the foreign policy of the USA and the UK on the one hand, and the media of those countries on the other hand, in relation to the Israeli–Palestinian conflict (see also Kellner, 2004, p 137; Detmer, 1995, p 91; El-Bilawi, 2011, p 130). Generally speaking, the four selected newspapers (GU, TL, NYT and WP) operate within political spectrums in their countries that support Israel over the Palestinians.

US foreign policy is characterised by its support of Israel. In an interviewFootnote 11 on US foreign policy and Israel, Jeremy R. HammondFootnote 12 (2013) states that “the U.S. supported Israel from its birth”. This support is prominent in the massive annual military and financial aid paid to Israel from the USA (Jeremy R. Hammond, 2013; see also Philo and Berry, 2011, p 76).

In the same vein, British foreign policy has substantial similarities with US foreign policy in relation to the Israeli–Palestinian conflict. Voltolini (2013, p 222) points out that the British policy 'has kept a strong link to Israel in line with the US stance' (see also Chomsky and Pappe, 2010, and Curtis, 2004). Furthermore, the United Kingdom and Israel have a strong and flourishing relationship. 'Bilateral trade was £3.85 billion in 2011, making Israel the United Kingdom’s largest individual trading partner in the Near East and North Africa region' (Voltolini, 2013, p 222). British foreign policy is typified by the statement of the British Foreign Secretary, William HagueFootnote 13, that 'Israel has a right to defend itself', without questioning how Israel’s borders should be defined or how a state can have 'rights'.

The Palestinians receive different treatment in US and UK foreign policies. In regard to US foreign policy and Palestinians, Karakoulaki (2013, p 4) points out that 'while he [Barack Obama] has declared that during his presidency, he will seek a fair solution for both sides; his administration has disagreed with almost every Palestinian move'. Also, US foreign policy focuses on blaming Palestinians for violence and requesting Hamas to end the violence and recognise past agreements and Israel’s ‘rights’ (see Karakoulaki, 2013, p 9). Similar to the US blaming of Palestinians, British foreign policy focuses on blaming Hamas. Again, William Hague makes a typical pronouncement: 'It is Hamas that bears principal responsibility for starting all of this' (Saleem, 2013).

The similar patterns of foreign policy in the USA and the UK lead to similar representation of Israelis and Palestinians in the selected newspapers. Jeremy R. HammondFootnote 14 (2013) suggests that “the mainstream media makes no secret of […] U.S. support for Israel, but it at the same time attempts to maintain the narrative of the U.S. as an honest broker”. He considers this role as a farce. This role of the media misleads the US public about the nature of the conflict in terms of political contexts.

In terms of journalistic practices, while it is proper to include the perspective of both warring sides, it becomes problematic and biased when news coverage systematically includes a greater context for the violence perpetrated by one side and omits that context in covering the violence of the other. This is clearly shown in the way the newspapers in this study report the efforts towards a ceasefire. This pattern casts Israel as an active partner for peace, while Palestinian Hamas continually rejects a ceasefire and refuses to stop its violence.

Ideological stances: liberal and conservative

This study is based on the premise that linguistic choices in texts carry ideological meaning(s), (see Amer, 2016, section 2.2.6). One reason to choose GU, TL, NYT and WP is their different ideological standpoints, being liberal or conservative (see section Data collection and sampling: the selected newspapers). I am convinced that this ideological difference is an important factor that will lead to different representation patterns of social actors.

In contrast, revisiting the linguistic mechanisms and representational processes reveals no major differences between the liberal newspapers (The Guardian and The New York Times) and the conservative newspapers (The Times London and The Washington Post). For example, in regard to the topic of ceasefire, all the US and UK newspapers foreground the Israeli efforts to achieve a ceasefire with the Palestinians to end the war. These findings can be explained by Khoury–Machool’s observation (2009, p 11) that 'while British journalists may be privately sympathetic to Palestinians, their filed reports of the Palestine–Israel conflict are often neutralised versions of witnessed events or, in many cases, of events recounted by official (i.e., Israeli) sources'. The findings of this study are in contrast with a statement by Kaposi (2014, p 1) where he claims that 'another [….] war is taking place in the British media to present and understand the events, with conservative publications taking it upon themselves to advocate Israeli interests and left-liberal ones supporting Palestinians'.

Generally speaking, ideologies, according to Van Dijk (1998a), determine the relations of a group to other social groups. In this study, the analysis of discourse practices was crucial to illuminate the representation patterns of the social groups. This study reveals that the supposed Palestinian danger and threat to Israel was prevalent across the four selected newspapers. This pattern paves the way to justify Israeli operations as self-defence (see also Allen’s, 2013 dissertation on BBC coverage of the Gaza war 2013).

Overall picture: an Israeli War against Hamas

The analysis shows that the British and American newspapers are similar in including the Israelis and Palestinians in ceasefire negotiations. The patterns represent Israelis as Israel and Israeli governmental and non-governmental actors. The Palestinian actors are represented as Hamas and Hamas members. From this analysis, there is no major or substantial difference between the British and American newspapers in their discourses regarding the coverage of the Gaza War of 2008–2009.

In regards to media power relations, on the Israeli side, we see an official view on the whole war. On the Palestinian side, we see only Hamas’ views and no views either from the Palestinian Authority or from the Palestinian Liberation OrganisationFootnote 15, the overarching resistance organisation for all Palestinians. This is a reason why some might distinguish between Hamas and Palestinians, even though Hamas is a major party in Palestine and won the Palestinian elections (in the West Bank as well as in Gaza) in 2006. This is in line with a finding from a recent study by Philo and Berry (2011) which states that the war is perceived as 'being directed only at Hamas, and this is certainly how Israel wished it to be seen' (p 155).

In this supposed war against Hamas, the clear message of the war is to stop Hamas’ rockets from being fired into Israel from the Gaza Strip. What is absent in the media coverage is Hamas’ terms for a ceasefire, namely lifting the Israeli siege on Gaza. Absence means the exclusion of views, in this case, those of Hamas.

Overall, the analysis suggests that the US and UK audiences (readers of the selected newspapers) did not have an adequate opportunity or sufficient information to learn about all sides of the war or to resist dominant interpretations.

This paper was restricted to the coverage of the Gaza war of 2008–2009 between 26.12.2008 and 18.01.2009 and focused on the representation of the Israeli and Palestinian actors in two newspapers from the USA (NYT and WP) and two newspapers from the UK (GU and TL). The paper does not claim that it has tackled all the linguistic structures but it is confined to examining the representation of social actors in reporting the Gaza war of 2008–2009.

Within this limitation, this study is not interested in highlighting who is right or wrong in their ideological stances, but in illuminating how meanings are reproduced and how social actors are represented. The paper’s contributions can be seen as addition to CDA studies on war reporting in general and the Gaza war of 2008–2009 in particular. It contributes to the examination absences and the mystification of social agents by CDA studies on media discourse and war reporting.

Data availability

All data analysed in this study are included in the paper.

Notes

El-Nawawy (2002, p 83) defines the foreign correspondents as 'those individuals who are stationed in countries other than that of their origin for the purpose of reporting on events and characteristics of the area of their stationing through news media based elsewhere'.

LexisNexis does not have complete records/archives of all newspapers. For this, I used Microfilm available at the library of Hamburg University.

On the LexisNexis research engine, articles have been researched online. 'The Times' newspaper is not available at LexisNexis; for this, I use the microfilm available at Hamburg University’s library to collect materials of 'The Times (London)' newspaper. Since the LexisNexis sorts only the material published on the print version of newspapers, microfilm has solved the problem in getting the material of 'The Times (London)'.

The publishing pages have different names across the newspapers but largely these pages have the same purposes.

In such cases, I quote only the relevant parts of the examples with a reference to the number of full examples.

Non-governmental actors are actors with no relation to the government but they have a political role and dimension in the war news reports.

The Israeli name of the Gaza war (2008–2009), see Gavriely-Nuri’s (2013, p 42)

For detailed discussion of definition of foreign policy, see Voltolini’s (2013) PhD dissertation.

An interview by Devon Douglas-Bowers on December 2013

Founding editor of Foreign Policy Journal and author of a book on ‘the US role in the Israeli Palestinian conflict’

Speaking on ‘Sixty years of British-Israeli diplomatic relations’ in March 2011’

Quoted from the same interview by Devon Douglas-Bowers, 2013

References

Ackerman S (2001) Al-Aqsa Intifada and the US Media. J Palest Stud 30(2):61–74

Adampa V (1999) Reporting of a violent crime in three newspaper articles. The representation of the female victim and the male perpetrator and their actions: A critical news analysis. In Centre for Language in Social Life, Working Papers Series (108), checked on 10 Jan 2011

Allen, P (2013) CDA approach to analysing BBC Television’s Newsnight reports on the Israel/Palestine conflict. MA TESOL and Applied Linguistics, University of Leicester, Leicester, MA

Almeida EP (2011) Palestinian and Israeli Voices in Five Years of U.S. Newspaper Discourse. Int J Commun 5:1586–1605

Amer M (2016) War reporting in the international press: A critical discourse analysis of the gaza war of 2008–2009. PhD thesis, Department of language, literature and media, University of Hamburg. http://ediss.sub.uni-hamburg.de/volltexte/2016/7899/

Androutsopoulos J (2010) Ideologizing ethnoloctal German. In: Johnson SA, Tommaso MM (eds) Language ideologies and media discourse. Texts, practices, politics, vol 10. Continuum, London, New York, p 182–202 (Advances in sociolinguistics)

Barkho L (2008) The BBC’S discursive strategy and practices vis-a-vis the Palestinian-Israeli conflict. Journal Stud 9(2):278–294.

Barkho L, Richardson JE (2010) A critique of BBC’s Middle East news production strategy. American Communication Journal 12(1):1–16.

Blommaert J (2005) Discourse: A critical introduction. Cambridge University Press, New York, NY

Chiluwa I (2011) Media Representation of Nigeria’s Joint Military Task Force in the Niger Delta Crisis. Int J Humanit Soc Sci 1(9):197–208

Chomsky N, Pappe I (2010) Gaza in crisis. Haymarket Books, Chicago

Connelly M, Welch D (2005) War and the media. Reportage and propaganda. In: Tauristhe B (ed) U.S. and Canada. St. Martins Press, London, New York, NY, p 1900–2003

Cordesman A, Moravitz J (2005) The Israeli-Palestinian war: Escalating to nowhere. In: Cooperation with the Center for Strategic and International Studies. Praeger Security International, Westport, CT, Washington, DC

Curtis M (2004) Britain’s real foreign policy and the failure of British Academia. Int Relat 18(3):275–287

Dardis F (2006) Military accord, media discord: A cross-national comparison of UK vs US press coverage of Iraq war protest. Int Commun Gaz 68(409):409–426

Detmer D (1995) Covering up Iran: Why vital information is routinely excluded from U.S. media news accounts. In: Kamalipour YR (ed) The U.S. media and the Middle East: Image and perception, vol 8. Greenwood Press, Westport, CT(Contributions to the study of mass media and communications, 46), p 91–101

Douglas-Bowers D (2013) The US role in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Foregin Policy J. http://www.foreignpolicyjournal.com/2013/12/02/the-u-s-role-in-the-israeli-palestinian-conflict/. Accessed 8 Mar 2015

El-Bilawi NH (2011) The war on Gaza: American and Egyptian media framing. In: Nasser I, Berlin LN, Wong S (eds) Examining education, media, and dialogue under occupation: The case of Palestine and Israel, vol 8. Multilingual Matters, Bristol, Buffalo (Critical language and literacy studies, 11), p 129–148

El-Nawawy M (2002) The Israeli-Egyptian peace process in the reporting of western journalists. Ablex, Westport, CT (Civic discourse for the third millennium)

Fairclough N (1989) Language and power. Longman, London, New York, NY (Language in social life series)

Fairclough N (1995a) Critical discourse analysis. The critical study of language.. Longman, London, New York, NY (Language in social life series)

Fairclough N (1995b) Media discourse. E. Arnold, London, New York, NY

Fairclough N (2001) Language and power, 2nd ed. Longman, Harlow, New York, NY (Language in social life series)

Fairclough N (2003) Analysing discourse: Textual analysis for social research. Routledge, London, New York, NY

Fairclough N (2014) What is CDA? Language and power twenty-five years on. https://www.academia.edu/8429277/What_is_CDA_Language_and_Power_twenty-five_years_on. Accessed 20 Feb 2015

Fairclough N, Wodak R (1997) Critical Discourse Analysis. In: van Dijk T (ed) Discourse as social interaction, Discourse studies: A multidisciplinary introduction, vol 2. Sage, London, p 258–284

Farrelly M (2015) Discourse and democracy: Critical analysis of the language of government. Routledge, New York, London

Fowler Roger (ed) (1991) Language in the news: Discourse and ideology in the press. Routledge, London; New York, NY

Gavriely-Nuri D (2013) The Normalization of War in Israeli Discourse 1967–2008. Lexington Books, Rowman and Littlefield Education, Lanham

Goddard P, Robinson P, Parry K (2008) Patriotism meets plurality: Reporting the 2003 Iraq War in the British press. In Media War Confl 1(1):9–30

Hallin DC, Mancini P (2004) Comparing media systems: Three models of media and politics. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, New York

Hansen M (2008) The Israel lobby and the Israeli-Palestinian peace process. J Polit Int Stud 26:3–16.

Jørgensen M, Phillips L (2002) Discourse analysis as theory and method. Sage, London, Thousand Oaks, California

Kamalipour YR (1995) Introduction. In: Kamalipour YR (ed) The U.S. media and the Middle East: Image and perception. Greenwood Press, Westport, CT, p 10–21

Kandil, MA (2009): The Israeli-Palestinian Conflict in American, Arab, and British Media: Corpus-based critical discourse analysis. Applied linguistics and english as a secon lnaugage dissertation the college of arts and sciences. Georgia State University. http://scholarworks.gsu.edu/alesl_diss/12. Accessed 10 Oct 2012

Kaposi D (2014) Violence and understanding in Gaza. The British broadsheets’ coverage of the war, vol 9. Palgrave Macmillan, London

Karakoulaki M (2013) The US Foreign Policy toward the Palestinian issue (2008-2012). Strategy Int 1:1–18

Kellner D (2004) The Persian Gulf TV war revisited. In: Allan S, Zelizer B (eds) Reporting war: Journalism in wartime, vol 7. Routledge, London, New York, NY

KhosraviNik, M (2008) British newspapers and the representation of refugees, asylum seekers and immigrants between 1996 and 2006. In: Working papers series. Centre for language in social life No. 128

KhosraviNik M (2010) Actor descriptions, action attributions, and argumentation. Towards a systematization of CDA analytical categories in the representation of social groups. Critical discourse studies 7(1):55–72

Khoury-Machool M (2009) British press representation of Yasir Arafat’s funeral1. J Arab Muslim Media Res 2(1, 2):5–22

Kress G (1990) Critical discourse analysis. Annu Rev Appl Linguist 11:84–99.

Mearsheimer JJ, Walt SM (2006) The Israel lobby and U.S. foreign policy. MIDDLE EAST POLICY XIII(3):29–87

Oganjanyan A (2012) The August war in Georgia: Foreign media coverage. Diplomica, Hamburg

Ozohu-Suleiman Y (2014) War journalism on Israel/Palestine: Does contra-flow really make a difference? Media War Confl 7(1):85–103.

Philo G (2012) Pictures and public relations in the Israeli–Palestinian conflict. In: Freedman Des, Thussu DK (eds) Media and terrorism: Global perspectives, vol 9. Sage, Los Angeles, p 151–164

Philo G, Berry M (2004) Bad news from Israel. Pluto Press, London, Sterling, VA

Philo G, Berry M (2011) More bad news from Israel. Pluto Press, London

Richardson JE (2007) Analysing newspapers: An approach from critical discourse analysis. Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke; New York

Saleem A (2013) In letter to activists, UK foreign office blames Palestinians in Gaza for bringing suffering on themselves. In: Electronic Intifada, available at https://electronicintifada.net/blogs/amena-saleem/letter-activists-uk-foreign-office-blames-palestinians-gaza-bringing-suffering. Accessed 5 May 2015

Seale C (2012) Researching society and culture, 3rd ed. Sage, London

Shreim N (2012) War in Gaza: A cross-cultural analysis of news reporting and reception. The case of BBC and Al-Jazeera. A Doctoral Thesis, Loughborough University, England. Loughborough’s Institutional Repository. https://dspace.lboro.ac.uk/dspace-jspui/

Slater J (2007) Muting the alarm over the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. The New York Times versus Haaretz, 2000–06. Int Secur 32(2):84–120.

Titscher et al. (2000) Methods of text and discourse analysis. Sage, London, Thousand Oaks, California

Tunstall J (1996) Newspaper power. The new national press in Britain. Clarendon Press; Oxford University Press, Oxford, New York

Van Dijk T (ed) (1997) Discourse as social interaction, vol 2. Sage, London

Van Dijk T (1998a) Opinions and ideologies in the press. Bell A, Garrett P (eds) Approaches to media discourse, vol 2. Blackwell, Oxford, Malden, Mass, p 21–63

Van Dijk T (1998b) Critical discourse analysis. In: Schiffrin D, Hamilton H & Tannen D (eds) Handbook of discourse analysis (in preparation). http://www.discourses.org/download/articles/

Van Leeuwen T (1996) The representation of social actors. In: Caldas-Coulthard CR, Coulthard M (eds) Texts and practices: Readings in critical discourse analysis, vol 3. Routledge, London, p 32–70

Van Leeuwen T (2008) Discourse and practice: New tools for critical discourse analysis. Oxford University Press, Oxford, New York, (Oxford studies in sociolinguistics)

Voltolini B (2013) Lobbying in EU foreign policy-making towards the Israeli-Palestinian conflict: Exploring the potential of a constructivist perspective. PhD thesis. The Department of International Relations, The London School of Economics and Political Science

Weiss G, Wodak R (2003) Theory and interdisciplinarity in critical discourse analysis. Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke

Wenden A (2005) The politics of representation: A critical discourse analysis of an Aljazeera special report. J Peace Stud 10(2):89–112

Williams K (2010) Read all about it! A history of the British newspaper. Routledge, London, New York, NY

Wodak R, Meyer M (eds) (2001) Methods of critical discourse analysis. Sage, London (Introducing qualitative methods)

Wooffitt R (2005) Conversation analysis and discourse analysis. A comparative and critical introduction. Sage, London, Thousand Oaks, California

Zanotti J et al. (2009) Israel and Hamas: Conflict in Gaza (2008–2009). United CRS report number: R40101. States Congressional Research Service, https://fas.org/sgp/crs/mideast/R40101.pdf

Acknowledgements

Dr Amer’s work is part of his PhD study which was funded by the German Academic Exchange Services (DAAD) from 2011 and 2015 at Hamburg University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declares no competing financial interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Amer, M. Critical discourse analysis of war reporting in the international press: the case of the Gaza war of 2008–2009. Palgrave Commun 3, 13 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-017-0015-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-017-0015-2