Abstract

Paleontologists and paleoanthropologists have long debated relationships between cranial morphology and diet in a broad diversity of organisms. While the presence of larger temporalis muscle attachment area (via the presence of sagittal crests) in carnivorans is correlated with durophagy (i.e. hard-object feeding), many primates with similar morphologies consume an array of tough and hard foods—complicating dietary inferences of early hominins. We posit that tapirs, large herbivorous mammals showing variable sagittal crest development across species, are ideal models for examining correlations between textural properties of food and sagittal crest morphology. Here, we integrate dietary data, dental microwear texture analysis, and finite element analysis to clarify the functional significance of the sagittal crest in tapirs. Most notably, pronounced sagittal crests are negatively correlated with hard-object feeding in extant, and several extinct, tapirs and can actually increase stress and strain energy. Collectively, these data suggest that musculature associated with pronounced sagittal crests—and accompanied increases in muscle volume—assists with the processing of tough food items in tapirs and may yield similar benefits in other mammals including early hominins.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Discerning the form–function relationship between skulls, teeth and diet is paramount to our understanding of ecology and evolution. The majority of paleoecological interpretations of Cenozoic mammals rests on the assumption that one can potentially infer the diets of extinct taxa by comparing their anatomical features to those of living species with known diets. Some relationships between craniodental form and function are well-established, such as the advent of high crowned and more molariform cheek teeth together with broadened muzzles that accompanied increased grazing in horses and their relatives1,2. Similarly, there is good evidence among primates that the mechanical properties of food items may impact skeletal and dental morphologies related to their ingestion and mastication3,4,5. As a result, anatomical attributes have been widely used in attempts to infer the dietary habits of extinct hominin species (e.g.6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13). However, the success that these biomechanical inferences have had for the retrodiction of hominin diets has been a matter of discussion14,15,16,17,18,19.

Much of the debate concerning the dietary habits of extinct hominins has focused on Paranthropus and, in particular, on the East African species P. boisei. Members of this genus are characterized by enlarged postcanine dentitions, cheek teeth with very thick enamel, dished faces in which the cheeks protrude anterior to the nasal aperture resulting in anteriorly placed masseteric muscle attachments, and sagittal and nuchal crests that are more pronounced, indicating enlarged temporalis muscles in comparison to species of Australopithecus such as A. afarensis and A. africanus20. These features, which bespeak an enhanced masticatory system have consistently been interpreted as adaptations to and testaments of hard-object feeding (e.g.7,8,9,13,21). However, the models that have been employed have not been without criticism14,16,17,22,23,24,25.

The microwear and isotopic signatures of P. boisei are inconsistent with the consumption of hard-foods26,27,28. Diet is not the same thing as dietary adaptation. As noted by Lee-Thorp29, these data should have portended the demise of the popular moniker—“Nutcracker Man” —for P. boisei. Nevertheless, the adaptationist paradigm persists9,21 despite the fact that both load magnitude and load frequency are implicated in osseous metabolic activity that results in alterations to bone mass and architecture30,31,32 and experimental evidence that hard object feeding, whether habitual or on an occasional “fallback” basis, does not explain the dentognathic morphology of P. boisei33.

There continues to be profound disagreement between morphological interpretations and dietary proxy data regarding the dietary ecology and functional significance of a suite of craniodental features of Paranthropus. Interpreting the dietary ecology and functional significance of the robust craniodental features of P. boisei is complicated by the lack of any extant primate analogues with a similar suite of features34.

As a well-studied group, carnivorous mammals, specifically members of the order Carnivora, are typically used as model organisms for interpreting the function of pronounced sagittal crests and large temporalis muscles, and in particular, are used to correlate these features with high bite forces and hard-object feeding (e.g.35). As expected, carnivorans with some of the largest and most pronounced sagittal crests, engage in durophagy and are capable of cracking bones open35; most notably—the spotted hyena, Crocuta crocuta. Finite element analysis (FEA) of C. crocuta demonstrates their ability to withstand increased stress from high bite forces36. Dental microwear also documents bone-cracking behavior in hyenas37,38,39,40, demonstrating hard-object feeding in all three species of extant hyenas while documenting softer food consumption (i.e., lower complexity values) in cheetahs with similar carnassial teeth39. Interestingly, the herbivorous giant panda (a member of Carnivora, Ailuropoda melanoleuca) also has a large sagittal crest41,42,43 yet has dental microwear indicative of tough and hard food items (see Materials and Methods for descriptions of DMTA attributes)44. This brings into question the ability to infer a correlation between crest morphology and diet, specifically for hard-object feeding45. While the examination of great apes with pronounced sagittal crests (e.g. gorillas and orangutans) may be revealing, no primate comparisons are perfect—many great apes consume hard and tough foods and the presence of sagittal crests is a sexually dimorphic trait, complicating understandings of morphological forms and functions13,17.

We suggest that tapirs (Tapirus; Tapiridae; Perissodactyla), being large herbivorous mammals that evince variable sagittal crest development among congeners, are a potential model for examining the correlation between the textural properties of food and morphology related to enhanced masticatory musculature. The sagittal crest of extant New World tapirs varies from a prominent, but low sagittal crest of less than 1 cm height in Tapirus pinchaque (the mountain tapir), a taller (greater than 4 cm in adults) and laterally compressed sagittal crest in Tapirus terrestris (the lowland, South American, or Brazilian tapir), and having a sagittal table rather than a sagittal crest in Tapirus bairdii (Baird’s tapir)46. Further, all tapirs are herbivorous and have similar tooth morphologies (low crowned and bilophodont teeth; enamel thickness is also similar among tapirs, with T. terrestris intermediate between T. bairdii and T. pinchaque; see supplemental methods, supplemental results, Supplemental Fig. 1 and Supplemental Table 1)47, yet they are known to eat variable degrees of tough leaves, fruits, hard seeds, and other foliage48,49,50,51,52,53,54). Specifically, T. bairdii is known to predate large seeds48,49,50, while T. terrestris and T. pinchaque consume a higher incidence of foliage (soft to tough foods)48,49,50,51,52,53,54. Extinct tapirs from the Pleistocene of North America that may also provide insight include: Tapirus haysii, T. lundeliusi, and T. veroensis. The closely related T. veroensis and T. haysii have lower sagittal crests (i.e. adult height is less than 2 mm)55,56 than the extinct T. lundeliusi, and extant T. pinchaque and T. terrestris. Only one fossil tapirid (even when compared to all tapirs including Old World tapirs), the dwarf tapir Tapirus polkensis, is characterized as having low parasagittal ridges that do not unite to form a sagittal crest ~75% of the time, with the other ~25% of adults having a sagittal crest when it occurs at the late Miocene to early Pliocene Gray Fossil Site (GFS) in Tennessee57. Previous work58 examined T. polkensis from the GFS, and extant tapirs from throughout the Americas to assess if age (as inferred from tooth eruption) or sexual dimorphism (in extant specimens with known sex data) played a role in sagittal crest formation, but data were equivocal. Further, sagittal crest morphology in Tapirus is not correlated with size, with T. terrestris being intermediate in size, but with the tallest crest57.

Understanding relationships between form, function, and diet requires a multi-proxy approach. FEA is capable of clarifying the potential for extant and extinct taxa to consume particular food types, i.e. their function, as inferred from the mechanical performance of the cranium—removing effects of size59,60,61,62,63. In contrast, dental microwear texture analysis (DMTA) has the potential to reveal the textural properties of food consumed during the past few days to weeks of an animal’s life64,65, and can clarify the dietary ecology of numerous extinct taxa; as compared to extant taxa with known diets (e.g.66,67,68). Here, we assess the functional significance of sagittal crest morphology as it relates to diet in several extant and extinct tapirs that exhibit a broad range of morphologies. In addition, we integrate FEA and DMTA to clarify the degree to which hard-object feeding is related to sagittal crest morphology in herbivorous tapirs. While relationships between DMTA, observed diet, and form are assessed, we also included extinct tapirs and associated DMTA data to increase the range of forms represented (including T. polkensis, which includes forms both with and without sagittal crests). These data have the potential to alter our understanding of relationships between the form and function of cranial morphology, including our understanding of the dietary ecology of early hominins, most notably P. boisei.

Results

Finite element analysis

Finite element analysis data are illustrated in Fig. 1, and summarized in Supplemental Tables 2–4. Figure 1 shows the von Mises (VM) stress distribution of each model during unilateral biting at the second and fourth premolar, and third molar. Highest stress was recorded on the biting side around the bite location and the anterior aspect of the orbit for all models. Distribution of stress shows that the peak moves posteriorly so that when biting at the third molar there is minimal stress on the premaxilla.

Results from finite element analysis. Predicted distribution of von Mises (VM) stresses across the cranial models of T. terrestris, T. bairdii, T. pinchaque and T. polkensis during unilateral biting at the second premolar (a), fourth premolar (b) and third molar (c) shown in lateral (top) and dorsal (bottom) views (warm colors indicate areas of high VM stress and cool colors indicate low stress; grey areas indicate VM stress that exceeds the specified maximum of 10 MPa). Strain energy and adjusted maximum VM stress (d) are also shown during unilateral biting at each bite point. Images (a–c) were produced using Abaqus CAE v6.14 (Simulia) software, based on CT data processed via Avizo v9.0 (FEI, part of Thermo Fisher Scientific) software.

The “adjusted” maximum stress (maximum stress after removing the top 2% of stress values to account for high stresses caused by point constraints) and strain energy are also shown in Fig. 1 for each bite point. Mean element stress, adjusted maximum stress, strain energy and mechanical efficiency for each model during unilateral biting at each tooth on the left side are shown in Supplemental Table 3, and for bilateral biting in Supplemental Table 4. As the bite point moves posteriorly along the tooth row, stress and strain generally decrease until the middle of the tooth row at approximately the first molar, where the stress and strain start increasing (Fig. 1d). Stress and strain in T. bairdii, however, increases along the tooth row so that both stress and strain are highest at the third molar (Fig. 1d, Supplemental Table 3). Performance varied between unilateral biting and bilateral biting so that some species performed better under one compared to the other (Supplemental Tables 3 and 4). Adjusted maximum stress (a proxy for strength) was lowest in T. bairdii for bilateral biting and T. polkensis for unilateral biting at all bite points, indicating that T. bairdii performed better in bilateral biting and T. polkensis performed better for unilateral biting (Fig. 1, Supplemental Tables 3 and 4). Maximum stress were highest in T. polkensis for bilateral biting at all bite points (Supplemental Table 4), further indicating that the T. polkensis model performed better under unilateral biting compared to bilateral biting. Mechanical efficiency increases in all models as the bite point moves posteriorly along the tooth row (Supplemental Tables 3 and 4).

Strain energy (a proxy for work efficiency, or the stiffness of the structure) also varied along the tooth row for each model, with the lowest strain energy generally in the center of the tooth row (Fig. 1). However, the T. bairdii model was stiffest and most efficient at the front of the tooth row, likely because of the extra stiffness provided by the ossified nasal septum, and less efficient at M3. The most compliant, and therefore least efficient model, was T. terrestris, indicating that it expends more energy on deformation. This species also has the highest and most developed sagittal crest. Mechanical efficiency, a measure of the efficiency at which muscle force is translated to bite force, was highest in T. bairdii and lowest in T. pinchaque at all bite locations during bilateral and unilateral biting.

Dental microwear texture analysis

Dental microwear textural data are illustrated in Figs. 2 and 3 and summarized in Table 1 and Supplemental Tables 5 and 6 (individual specimen data are included in Supplemental Table 7). Complexity of T. bairdii is significantly greater than T. terrestris and T. pinchaque, and T. terrestris is also significantly greater than T. pinchaque (Table 1). T. bairdii also has significantly greater Tfv than T. terrestris (Table 1). Anisotropy of T. pinchaque is significantly greater than T. bairdii, yet indistinguishable from T. terrestris (Table 1). None of the extant tapirs can be distinguished using either HAsfc metric (3×3 or 9×9); this metric is therefore not discussed further or used to compare with extinct taxa.

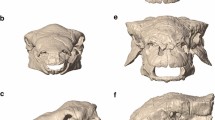

3D surface renderings for extant (a–c) and extinct tapirs (d–g). Three-dimensional surface renderings of the following museum specimens are included: Tapirus bairdii (a, FMNH 34665), T. terrestris (b, FMNH 34264), T. pinchaque (c, FMNH 70557), T. polkensis (d, ETMNH 6820), T. hasyii (e, UF 89533), T. lundeliusi (f, UF 224674), and T. veroensis (g, UF 210890). All surface renderings (a–g) were produced via SensoMAP software (Sensofar).

When extinct and extant tapirs are compared, T. polkensis from the GFS are distinctly different from North American Pleistocene tapirs (T. haysii, T. lundeliusi, and T. veroensis) in nearly all DMTA attribute comparisons (with lower Asfc, higher epLsar, and lower Tfv values); with an exception, T. polkensis is not significantly lower in Asfc or Tfv than T. lundeliusi (Figs. 2 and 3; Table 1). T. polkensis is most similar to T. pinchaque (indistinguishable in Asfc, epLsar and Tfv) and T. terrestris (indistinguishable in epLsar and Tfv), whereas T. polkensis has significantly lower Asfc and Tfv than T. bairdii (Table 1). The now extinct Pleistocene tapirs here examined are indistinguishable from one another in all DMTA attributes, with the exception that T. lundeliusi has significantly lower Asfc than T. veroensis and significantly lower Tfv than both T. haysii and T. veroensis (Table 1). All Pleistocene tapirs are indistinguishable from T. bairdii in Asfc, epLsar, and Tfv, with the exception of T. lundeliusi having lower epLsar and Tfv than T. bairdii (Table 1). Further, Pleistocene tapirs are significantly different from the extant T. pinchaque and T. terrestris in most attributes, with a few exceptions noted in Table 1 (i.e. T. lundeliusi and T. haysii are indistinguishable from T. terrestris in Asfc and epLsar, respectively; T. haysii cannot be distinguished from T. pinchaque with Tfv; and T. lundeliusi is indistinguishable from both T. pinchaque and T. terrestris with Tfv).

Despite variable sagittal crest morphology in specimens of GFS T. polkensis, there were no apparent relationships between DMTA attributes and sagittal crest development (the presence or absence of a sagittal crest in adult specimens; noted in Supplemental Table 7, although adult specimens with preserved crania and dental microwear were limited).

Discussion

FEA results suggest that the presence of a sagittal crest can affect both the energy efficiency (the amount of deformation) and strength (measured by stress) of the cranium in tapirs as it does in carnivorans36,60,69. The tapir with the most pronounced sagittal crest (T. terrestris) has the highest strain energy (low energy efficiency) and therefore more readily deforms. T. terrestris consumes seeds and fruits, potentially more fruits than T. bairdii based on stomach contents50,51,52, but isotopic evidence suggests that in rainforests they may be more folivorous (as suggested by ref. 53 based on a significant correlation between carbon and oxygen isotope values of tooth enamel, of many of the same specimens examined here for DMTA, linking leaf water and canopy density which is likely only possible if primarily consuming leaf material). A pronounced sagittal crest may confer benefits related to increased temporalis muscle volume—allowing for prolonged mastication which is particularly beneficial when consuming tough-food items with lower nutritional value. However, the presence or development of a sagittal crest (and accompanied larger temporalis muscles) does not appear to be a prerequisite for hard-object feeding as a softer and tougher diet for T. terrestris is supported by DMTA. DMTA further suggests that T. terrestris consumes softer food items than its congener, T. bairdii (based on significantly lower Asfc values).

The presence of a sagittal table instead of a sagittal crest in T. bairdii results in lower stress and lower strain energy, and coincides with hard-object feeding revealed by DMTA. T. bairdii typically occurs in drier forests than T. terrestris and is known to predate large seeds (from 20–30 mm), including those of Manilkara zapota (commonly known as the sapodilla)48,49,50. In the Calakmul region of Mexico only 53% of dung piles contained intact seeds (noted in ref. 58), suggesting that T. bairdii is in fact extracting nutrients from these seeds during mastication. Thus, ecological studies, FEA and DMTA all suggest that T. bairdii is both capable of and actually consumes hard-objects, e.g. seeds. Interestingly, the protruding and ossified nasal septum may have further improved their ability to consume hard-objects and it may be partly responsible for lower overall stress and strain energy, particularly when biting at anterior teeth, by reducing dorsoventral bending.

FEA and DMTA data of extinct tapirs are variable with some showing evidence of hard-object feeding, and others not. Data from FEA of T. polkensis suggests it has a strong skull when modeling unilateral biting but weak for bilateral biting. DMTA suggests a highly folivorous diet and the absence of significant hard-object feeding, despite hickory nuts being found in the stomach region of these fossil specimens and the species yielding highly variable sagittal crest morphology58. However, FEA suggests the potential ability to consume hard-objects during unilateral biting. Other extinct Pleistocene tapirs (e.g., T. haysii, T. lundeliusi, and T. veronesis) have sagittal crests (with T. haysii and T. veroensis having reduced sagittal crests less than 2 mm in height)55,56, and primarily consume hard-objects (as evinced by indistinguishable Asfc values from T. bairdii)—although, T. lundeliusi is also indistinguishable from T. terrestris. While FEA was not possible on these taxa, a reduced sagittal crest does correlate with hard-object feeding (via DMTA) in extinct taxa, suggesting that reduced sagittal crests in extinct taxa and the absence of sagittal crests in extant T. bairdii may have been better able to handle higher stress loads than taxa with more pronounced sagittal crests—although further work is needed.

Collectively, FEA, DMTA, and ecological data suggest that the presence of moderate to pronounced sagittal crests in extant tapirs does not correlate with hard-object feeding, but rather with processing of tough and/or less nutritious vegetative matter—including more folivorous diets. FEA and DMTA largely agree, with the extant tapirs exhibiting sagittal crests (both T. pinchaque and T. terrestris) eating tougher and softer foods, whereas T. bairdii is both more capable of eating harder foods (low stress and strain) and exhibits this behavior as evinced by DMTA (done here) and observed dietary behavior48,49,50,51,52,53,54. Therefore, sagittal crest morphology in herbivores does not equate to hard-object feeding; in fact, the opposite is true in extant tapirs. Examination of fossil tapirs suggests that relationships between diet and morphology are not exact; tapirs with reduced sagittal crests or sagittal tables tend to consume harder foods—with the notable exception of the variable T. polkensis which exemplifies both morphotypes. These data suggest that sagittal crests in herbivorous tapirs may confer different functional advantages than in carnivorans—a sagittal crest allows attachment for larger temporalis muscles in both taxa, providing higher bite force in bone-cracking carnivorans and allowing for increased masticatory processing of tough food in tapirs.

Our combined FEA and DMTA analyses shed light on the functional significance of the sagittal crest and have broad implications for how we interpret mammalian ecology, including that of hominins. For over sixty years anthropologists have investigated and debated the diets of the “gracile” and “robust” australopithecines, the latter including P. boisei70. Despite an early study which suggested that the presence of sagittal crests in ancient hominins is related to allometry (i.e. with increased body size a sagittal crest provides increased muscle attachment area, if brain size does not increase)71,72, the vast majority of studies to date suggest that the disparate craniodental morphology of the “gracile” and “robust” forms stems from dietary differences—although what these diets are is disputed9,14,21,26,27,28,59,64,73,74,75,76. Sagittal crest formation is often noted to occur in mammals with diets that require the consumption of either very hard or tough foods (e.g. hyenas, giant pandas) which require increased muscle volume and muscle attachment area35,36,37,38,39,41,42,43,44,48,49,50,51,52,53,54. In primates, the apes with sagittal crests (i.e. gorillas and orangutans) are also known to consume very tough and/or hard food items, and recent studies have demonstrated relationships between the properties of food (e.g. fracture toughness) and jaw muscle activity/jaw robusticity—which subsequently requires increased muscle mass and a sagittal crest77,78. From our analysis of tapirs, sagittal crests and associated craniodental morphologies may confer benefits by allowing for prolonged chewing of tough and/or less nutritious foliage, while the tapirs eating hard food items either lack or have less pronounced sagittal crests relative to body size (than T. terrestris, for example).

In contrast to extant tapirs which exhibit disparate diets and morphologies, the congeners P. boisei and P. robustus exhibit similar morphologies yet proxy evidence suggests different diets. Specifically, the robust masticatory morphology of Paranthropus59,64,73,79 may have conferred multiple advantages in P. boisei and P. robustus, with the former able to process tougher and/or less nutritious herbaceous matter (potentially for a prolonged period of time) while the latter was capable of eating harder food items. Alternatively, the ability to consume both tough and hard foods for prolonged periods may also have been possible59. While morphological and FEA results suggest that P. boisei was capable of eating hard-objects9,59 (much like P. robustus), dental microwear, stable isotope, and plant biomarker evidence point to a diet that may have been dominated by softer and/or more abrasive foods (e.g. grasses, ferns, sedges, and aquatic food sources)—likely specializing on tough C4 grasses10,11,12, 682628,75,80. Much like late Cenozoic horses with high-crowned teeth, which were capable of eating abrasive grasses but many times consumed a mixture of browse and grass1,2, potential and realized diets are not always in agreement. Most notably, and as revealed here, relationships between form, function, and diet are complex and require multiple lines of evidence and a diverse suite of extant analogs. Further, herbivorous analogues such as tapirs are important models for inferring dietary relationships as revealed by morphology and suggest that pronounced sagittal crests can be advantageous and correlated with softer/tougher diets in mammalian herbivores.

Materials and Methods

Finite element analysis

Crania and mandibles representing four species of tapirs were CT scanned at the University of Texas High-Resolution X-ray CT Facility (UTCT) in Austin, Texas. The scanned material was provided by the following institutions: the Texas Memorial Museum (TMM), the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH), the Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, Berkeley (MVZ), and the East Tennessee State University and General Shale Brick Natural History Museum and Visitor Center (ETMNH). Specimens used in the finite element analysis include:

Tapirus terrestris

TMM M-16; San Antonio Zoo; scanned with an interslice spacing of 1.0 mm, and an interpixel spacing of 0.5918 mm.

Tapirus bairdii

AMNH 80076; Honduras, near Tela; scanned with an interslice spacing of 1.0 mm, and an interpixel spacing of 0.5468 mm.

Tapirus pinchaque

MVZ 124091; Rio San Jose, 2700 m, Moscapan, Huila, Colombia; scanned with an interslice spacing of 0.7 mm, and an interpixel spacing of 0.2197 mm.

Tapirus polkensis

ETMNH 3519; Gray Fossil Site; voxel size = 0.1694 mm. This specimen represents one of the ~25% of specimens which have a single sagittal crest.

CT data were processed in Avizo v9.0 (FEI, part of Thermo Fisher Scientific), where the cranium was separated from the mandible and 3D surface reconstructions were generated. The surface meshes were then cleaned and converted to solid volume meshes composed of 4-node tetrahedral elements of between 1.3 million and 2.1 million elements (see Supplemental Table 2) and exported as Abaqus input files (*.inp) for analysis in Abaqus CAE v6.14 (Simulia).

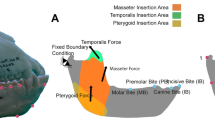

Muscle force estimates where produced using the dry skull method81 from digital models in their original size, and applied to the skulls by distributing the load over the temporalis, masseter, and pterygoid muscle origins. Muscle orientations were determined by creating a local coordinate system between the origin and the corresponding insertion on the mandible. Each model was constrained by a single node at both temporomandibular joints (TMJ) and at each bite point for unilateral and bilateral biting at each premolar (P2-P4) and molar (M1-M3). For bilateral biting, maximum muscle contraction was simulated on both sides, whereas for unilateral biting, the balancing-side (non-biting side) was adjusted to 60% of the maximum muscle force. The left TMJ was fully constrained against translation in any axis, the right TMJ was constrained in the y- and z- axis to allow lateral displacement of the skull, and the bite point(s) were constrained in only the axis perpendicular to the occlusal plane. All models were assigned as homogeneous and isotropic with average values of Young’s modulus (E = 20 GPa) and Poisson’s ratio (ν = 0.3) for mammalian bone82, and all analyses were linear and static.

Due to the variation in size among the tapir species, the models were standardized to the same size for comparison of shape alone. To compare the stress (strength) between models, the models were scaled to the same muscle force: surface area ratio, and to compare strain, the models were scaled to have equal force: volume ratios (following ref. 83). Von Mises stress, strain energy (an indicator of work efficiency) and mechanical efficiency were analyzed to compare the biomechanical performance between the models.

Dental microwear texture analyses

Dental microwear replicas of extant (T. bairdii, T. pinchaque, and T. terrestris; n = 55) and extinct (Tapirus haysii, T. lundeliusi, T. polkensis, and T. veroensis; n = 51; see supplemental materials for samples sizes per each extant and extinct taxon) New World tapir species were prepared by molding and casting using polyvinylsiloxane dental impression material (President’s Jet regular body, Coltène-Whaledent Corp., Cuyahoga Falls, OH, USA) and Epotek 301 epoxy resin and hardener (Epoxy Technologies Corp., Billerica, MA, USA), respectively. Extant faunal specimens were accessed in collections housed in the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH; New York City, NY, USA), the Field Museum of Natural History (FMNH; Chicago, IL, USA), and the Yale Peabody Museum (YPM; New Haven, CT, USA). Extinct faunal specimens were examined from the East Tennessee Museum of Natural History and Gray Fossil Site (ETMNH; Johnson City, TN, USA), the Florida Museum of Natural History (UF; Gainesville, FL, USA), and the Texas Memorial Museum (TMM; Austin, TX, USA). Dental microwear texture analysis (DMTA) using white-light confocal profilometry and scale-sensitive fractal analysis (SSFA), was performed on all replicas of bilophodont teeth that preserved ante-mortem microwear similar to prior work (e.g.37,38,66,67,84,85,86,87,88.

All specimens were scanned in three dimensions in four adjacent fields of view, for a total sampled area of 204 × 276 µm2 and subsequently analyzed using SSFA software (ToothFrax and SFrax, Surfract Corp., www.surfrait.com) to characterize tooth surfaces according to the variables of anisotropy (epLsar), complexity (Asfc), heterogeneity of complexity (HAsfc), and textural fill volume (Tfv). Anisotropy is the degree to which surfaces show a preferred orientation, such as the dominance of parallel striations having more anisotropic surfaces (as is typical in folivores and grazers)66,67,68,86,89,90,91,95. Complexity is the change in surface roughness with scale and used to distinguish taxa that consume hard, brittle foods from those that eat softer/tougher ones66,67,68,84,89,95. Heterogeneity (HAsfc3x3 and HAsfc9x9), the degree of texture complexity variation, is measured by calculating Asfc variation among subdivided samples (a 3 × 3 and 9 × 9 grid, totaling 9 to 81 subsamples, respectively)66,67. Thus, surfaces with high heterogeneity have greater disparity in complexity values between subdivided samples. Lastly, textural fill volume (Tfv) measures the volume filled by large (10 µm diameter) and small (2 µm diameter) square cuboids, with high Tfy values indicating potentially deeper and/or larger features38,67,87.

All statistical analyses follow the same methods of prior DMTA analyses [e.g., 38,86,87]. As dental microwear texture analysis variables are typically non-normally distributed (Shapiro-Wilk tests, p > 0.05), we used non-parametric statistical tests (Kruskal-Wallis and Dunn’s procedure) to conduct multiple comparisons between all extant taxa, and all taxa (extant and extinct) absent of the Bonferroni correction (as the Bonferroni correction increases the probability of false negatives, Type II errors)92,93,94.

Ethics and data accessibility

All specimens examined were from publically accessible collections as described in the materials and methods section. No permits or permissions were needed to examine these previously collected museum specimens. All primary data are included in the referenced supplemental files.

References

MacFadden, B. J., Cerling, T. E., Harris, J. M. & Prado, J. Ancient latitudinal gradients of C3/C4 grasses interpreted from stable isotopes of New World Pleistocene horse (Equus) teeth. Global Ecol. Biogeogr. 8, 137–149 (1999).

MacFadden, B. J. Fossil horses–evidence for evolution. Science 307, 1728–1730 (2005).

Kay, R. F. The functional adaptations of primate molar teeth. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 43, 195–215 (1975).

Wright, B. W. Craniodental biomechanics and dietary toughness in the genus Cebus. J. Hum. Evol. 48, 473–492 (2005).

Menegaz, R. A. et al. Evidence for the influence of diet on cranial form and robusticity. Anat. Rec. 293, 630–641 (2010).

Du Brul, E. L. Early hominid feeding mechanisms. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 47, 305–320 (1977).

Lucas, P. W., Constantino, P. J. & Wood, B. A. Inferences regarding the diet of extinct hominins: structural and functional trends in dental and mandibular morphology within the hominin clade. J. Anat. 212, 486–500 (2008).

Rak, Y. The Australopithecine Face. (New York: Academic Press, 1983).

Smith, A. L. et al. The feeding biomechanics and dietary ecology of Paranthropus boisei. Anat. Rec. 298, 145–167 (2015).

Strait, D. S. et al. The feeding biomechanics and dietary ecology of Australopithecus africanus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 106, 2124–2129 (2009).

Ledogar, J. A. et al. Mechanical evidence that Australopithecus sediba was limited in its ability to eat hard foods. Nat. Commun. 7(7), 10596, https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms10596 (2016).

Ungar, P. S. Dental topography and human evolution with comments on the diets of Australopithecus africanus and Paranthropus robustus in Dental Perspectives on Human Evolution: State of the Art Research in Dental Anthropology (eds. Bailey, S., Hublin, J. J.) 321–344 (Springer, Dordrecht, 2007).

Wood, B. A. & Schroer, K. Reconstructing the diet of an extinct hominin taxon: the role of extant primate models. Int. J. Primatol. 33, 716–742 (2012).

Daegling, D. J. et al. Viewpoints: feeding mechanics, diet, and dietary adaptations in early hominins. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 151, 356–371 (2013).

Daegling, D. J. & Grine, F. E. Feeding behaviour and diet in Paranthropus boisei: the limits of functional inference from the mandible in Human Paleontology and Prehistory: Contributions in Honor of Yoel Rak (eds. Marom, A., Hovers, E.) 109-125 (Springer, Dordrecht, 2017).

Grine, F. E. et al. Craniofacial biomechanics and functional and dietary inferences in hominin paleontology. J. Hum. Evol. 58, 293–308 (2010).

Grine, F. E. & Daegling, D. J. Functional morphology, biomechanics and the retrodiction of early hominin diets. Comptes. Rendus. Palevol. 16, 613–631 (2017).

Ross, C. F. & Iriarte-Diaz, J. What does feeding system morphology tell us about feeding? Evol. Anthropol 23, 105–120 (2014).

Ross, C. F., Iriarte-Diaz, J. & Nunn, C. L. Innovative approaches to the relationship between diet and mandibular morphology in primates. Int. J. Primatol. 33, 632–660 (2012).

Kimbel, W. H., Rak, Y. & Johanson, D. C. The Skull of Australopithecus afarensis. (Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2004).

Strait, D. S. et al. Viewpoints: diet and dietary adaptations in early hominins: the hard food perspective. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 151, 339–355 (2013).

Ravosa, M. J. et al. Adaptive plasticity in the mammalian masticatory complex: you are what, and how, you eat. In Primate Craniofacial Biology and Function (eds. Vinyard, C. J., Ravosa, M. J. & Wall, C. E.) 293–328 (Springer, New York, 2013).

Ravosa, M. J., Menegaz, R. A., Scott, J. E., Daegling, D. J. & McAbee, K. R. Limitations of a morphological criterion of adaptive inference in the fossil record. Biol. Rev. 91, 883–898 (2016).

Toro-Ibacache, V., Zapata Muñoz, V. & O’Higgins, P. The relationship between skull morphology, masticatory muscle force and cranial skeletal deformation during biting. Ann. Anat. 203, 59–68 (2016).

Toro-Ibacache, V., Fitton, L. C., Fagan, M. J. & O’Higgins, P. Validity and sensitivity of a human cranial finite element model: implications for comparative studies of biting performance. J. Anat. 228, 70–84 (2016).

Ungar, P. S., Grine, F. E. & Teaford, M. F. Dental microwear and diet of the Plio-Pleistocene hominin Paranthropus boisei. Plos One 3, e2044, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0002044 (2008).

Grine, F. E., Sponheimer, M., Ungar, P. S., Lee‐Thorp, J. & Teaford, M. F. Dental microwear and stable isotopes inform the paleoecology of extinct hominins. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 148, 285–317 (2012).

Cerling, T. E. et al. Diet of Paranthropus boisei in the early Pleistocene of East Africa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108, 9337–9341 (2011).

Lee-Thorp, J. The demise of “Nutcracker Man”. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108, 9319–9320 (2011).

Judex, S., Lei, X., Han, D. & Rubin, C. Low-magnitude mechanical signals that stimulate bone formation in the ovariectomized rat are dependent on the applied frequency but not on the strain magnitude. J. Biomech. 40, 1333–1339 (2006).

Ozcivici, E. et al. Mechanical signals as anabolic agents in bone. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 6, 50–59 (2009).

Ravosa, M. J., Kunwar, R., Stock, S. R. & Stack, M. S. Pushing the limit: masticatory stress and adaptive plasticity in mammalian craniomandibular joints. J. Exp. Biol. 210, 628–641 (2007).

Scott, J. E., McAbee, K. R., Eastman, M. M. & Ravosa, M. J. Experimental perspectives on fallback foods and dietary adaptations in early hominins. Biol. Lett. 10, 20130789, https://doi.org/10.1098/rsbl.2013.0789 (2014).

Wood, B. & Schroer, K. Reconstructing the diet of an extinct hominin taxon: the role of extant primate models. Int. J. Primatol. 33, 716–742 (2010).

Van Valkenburgh, B. Déjà vu: the evolution of feeding morphologies in the Carnivora. Integr. Comp. Biol. 47, 147–163 (2007).

Tanner, J. B., Dumont, E. R., Sakai, S. T., Lundrigan, B. L. & Holekamp, K. E. Of arcs and vaults: the biomechanics of bone‐cracking in spotted hyenas (Crocuta crocuta). Biol. J. Linn. Soc 95, 246–255 (2008).

Schubert, B. W., Ungar, P. S. & DeSantis, L. R. G. Carnassial microwear and dietary behaviour in large carnivorans. J. Zool 280, 257–263 (2010).

DeSantis, L. R. G., Schubert, B. W., Scott, J. R. & Ungar, P. S. Implications of diet for the extinction of saber-toothed cats and American lions. PloS One 7, e52453, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0052453 (2012).

DeSantis, L. R. G. et al. Assessing niche conservatism using a multi-proxy approach: dietary ecology of extinct and extant spotted hyenas. Paleobiology 43, 286–303 (2017).

Van Valkenburgh, B., Teaford, M. F. & Walker, A. Molar microwear and diet in large carnivores: inferences concerning diet in the sabretooth cat, Smilodon fatalis. J. Zool 222, 319–340 (1990).

Davis, D. D. The giant panda: a morphological study of evolutionary mechanisms (Vol. 3) (Chicago Natural History Museum, Chicago, 1964).

Jin, C. et al. The first skull of the earliest giant panda. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104, 10932–10937 (2007).

Figueirido, B., Tseng, Z. J., Serrano-Alarcón, F. J., Martín-Serra, A. & Pastor, J. F. Three-dimensional computer simulations of feeding behaviour in red and giant pandas relate skull biomechanics with dietary niche partitioning. Biol. Letters 10, 20140196, https://doi.org/10.1098/rsbl.2014.0196 (2014).

Donohue, S. L., DeSantis, L. R. G., Schubert, B. W. & Ungar, P. S. Was the giant short-faced bear a hyper-scavenger? A new approach to the dietary study of ursids using dental microwear textures. PloS One 8, e77531, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0077531 (2013).

Tseng, Z.J. & Flynn, J.J. Structure-function covariation with nonfeeding ecological variables influences evolution of feeding specialization in Carnivora. Science Advances 4, eaao5441, https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aao5441 (2018).

Holbrook, L. T. The unusual development of the sagittal crest in the Brazilian tapir (Tapirus terrestris). J. Zool 256, 215–219 (2002).

DeSantis, L. R. G. & MacFadden, B. Identifying forested environments in deep time using fossil tapirs: evidence from evolutionary morphology and stable isotopes. Cour. Forsch.-Inst. Senckenberg 15, 147–157 (2007).

Janzen, D. H. Seeds in tapir dung in Santa Rosa National Park, Costa Rica. Brenesia 19/20, 129–135 (1982).

Williams, K.D. The Central American Tapir (Tapirus bairdii Gill) in northwestern Costa Rica. (Michigan State University, Michigan, 1984).

O’Farrill, G., Galetti, M. & Campos-Arceiz, A. Frugivory and seed dispersal by tapirs: an insight on their ecological role. Integr. Zool 8, 4–17 (2013).

Bodmer, R. E. Fruit patch size and frugivory in the lowland tapir (Tapirus terrestris). J. Zool 222, 121–128 (1990).

Henry, O., Feer, F. & Sabatier, D. Diet of the lowland tapir (Tapirus terrestris L.) in French Guiana. Biotropica 32, 364–368 (2000).

DeSantis, L. R. G. Stable isotope ecology of extant tapirs from the Americas. Biotropica 43, 746–754 (2011).

Downer, C. C. Observations on the diet and habitat of the mountain tapir (Tapirus pinchaque). J. Zool. 254, 279–291 (2001).

Hulbert, R. C. & Wallace, S. C. Phylogenetic analysis of late Cenozoic Tapirus (Mammalia, Perissodactyla. J. Vert. Paleontol. 25, 72A (2005).

Hulbert, R. C. A new early Pleistocene tapir (Mammalia: Perissodactyla) from Florida, with a review of Blancan tapirs from the state. Bull. Fla. Mus. Nat. Hist 49, 67–126 (2010).

Hulbert, R. C., Wallace, S. C., Klippel, W. E. & Parmalee, P. W. Cranial morphology and systematics of an extraordinary sample of the late Neogene dwarf tapir, Tapirus polkensis (Olsen). J. Paleontol. 83, 238–262 (2009).

Abernethy, A. R. Extreme variation in the sagittal crest of Tapirus polkensis (Mammalia, Perissodactyla) at the Gray Fossil Site Northeastern TN. Electronic Theses and Dissertations. dc.etsu.edu/etd/1348 (2011).

Wroe, S., Ferrara, T.L., McHenry, C.R., Curnoe, D. & Chamoli, U. The craniomandibular mechanics of being human. Proc. Roy. Soc. Lond. B. 277, https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2010.0509 (2010).

Tseng, Z. J. Cranial function in a late Miocene Dinocrocuta gigantea (Mammalia: Carnivora) revealed by comparative finite element analysis. Biol. J. Linn. Soc 96, 51–67 (2009).

Attard, M. R. G., Chamoli, U., Ferrara, T. L., Rogers, T. L. & Wroe, S. Skull mechanics and implications for feeding behaviour in a large marsupial carnivore guild: the thylacine, Tasmanian devil and spotted‐tailed quoll. J. Zool. 285, 292–300 (2011).

Sharp, A. C. Comparative finite element analysis of the cranial performance of four herbivorous marsupials. J. Morphol. 276, 1230–1243 (2015).

Snively, E., Fahlke, J. M. & Welsh, R. C. Bone-breaking bite force of Basilosaurus isis (Mammalia, Cetacea) from the Late Eocene of Egypt estimated by finite element analysis. PloS One 10, e0118380, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0118380 (2015).

Grine, F. E. Dental evidence for dietary differences in Australopithecus and Paranthropus: a quantitative analysis of permanent molar microwear. J. Hum. Evol. 15, 783–822 (1986).

Teaford, M. F. & Oyen, O. J. In vivo and in vitro turnover in dental microwear. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 80, 447–460 (1989).

Scott, R. S. et al. Dental microwear texture analysis shows within-species diet variability in fossil hominins. Nature 436, 693–695 (2005).

Scott, R. S. et al. Dental microwear texture analysis: technical considerations. J. Hum. Evol. 51, 339–349 (2006).

DeSantis, L. R. G. Dental microwear textures: reconstructing diets of fossil mammals. Surf. Topogr 4, 023002, https://doi.org/10.1088/2051-672X/4/2/023002 (2016).

Oldfield, C. C. et al. Finite element analysis of ursid cranial mechanics and the prediction of feeding behaviour in the extinct giant Agriotherium africanum. J. Zool. 286, 163–170 (2012).

Robinson, J. T. Prehominid dentition and hominid evolution. Evolution 8, 324–334 (1954).

Wolpoff, M. H. Sagittal cresting in the South African australopithecines. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol 40, 397–408 (1974).

Wood, B. A. & Stack, C. G. Does allometry explain the differences between “Gracile” and “Robust” australopithecines? Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 52, 55–62 (1980).

Peters, C. R. Nut‐like oil seeds: Food for monkeys, chimpanzees, humans, and probably ape‐men. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol 73, 333–363 (1987).

Teaford, M. F. & Ungar, P. S. Diet and the evolution of the earliest human ancestors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97, 13506–13511 (2000).

Martínez, L. M., Estebaranz-Sánchez, F., Galbany, J. & Pérez-Pérez, A. Testing dietary hypotheses of East African hominines using buccal dental microwear data. PloS One 11, e0165447, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0165447 (2016).

Ungar, P. S. & Sponheimer, M. The diets of early hominins. Science 334, 190–193 (2011).

Taylor, A. B., Vogel, E. R. & Dominy, N. J. Food material properties and mandibular load resistance abilities in large-bodied hominoids. J. Hum. Evol. 55, 604–616 (2008).

Vogel, E. R. et al. Food mechanical properties, feeding ecology, and the mandibular morphology of wild orangutans. J. Hum. Evol. 75, 110–124 (2014).

Tobias, P.V. Olduvai Gorge (Vol. 2) The Cranium and Maxillary Dentition of Australopithecus (Zinjanthropus boisei) (London: Cambridge University Press 1967).

Magill, C. R., Ashley, G. M., Domínguez-Rodrigo, M. & Freeman, K. H. Dietary options and behavior suggested by plant biomarker evidence in an early human habitat. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 113, 2874–2879 (2016).

Thomason, J. J. Cranial strength in relation to estimated biting forces in some mammals. Can. J. Zool. 69, 2326–2333 (1991).

Erickson, G. M., Catanese, J. & Keaveny, T. M. Evolution of the biomechanical material properties of the femur. Anat. Rec. 268, 115–124 (2002).

Dumont, E. R., Grosse, I. R. & Slater, G. J. Requirements for comparing the performance of finite element models of biological structures. J. Theor. Biol. 256, 96–103 (2009).

Ungar, P. S., Brown, C. A., Bergstrom, T. S. & Walker, A. Quantification of dental microwear by tandem scanning confocal microscopy and scale-sensitive fractal analyses. Scanning 25, 185–193 (2003).

Ungar, P. S., Merceron, G. & Scott, R. S. Dental microwear texture analysis of Varswater Bovids and Early Pliocene paleoenvironments of Langebaanweg, Western Cape Province, South Africa. J. Mammal. Evol 14, 163–181 (2007).

Prideaux, G. J. et al. Extinction implications of a chenopod browse diet for a giant Pleistocene kangaroo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106, 11646–11650 (2009).

DeSantis, L. R. G. et al. Direct comparison of 2D and 3D dental microwear proxies in extant herbivorous and carnivorous mammals. PloS One 8, e71428, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0071428 (2013).

DeSantis, L. R. G. & Haupt, R. J. Cougars’ key to survival through the Late Pleistocene extinction: insights from dental microwear texture analysis. Biol. Letters 10, 2014.0203, https://doi.org/10.1098/rsbl.2014.0203 (2014).

Scott, J. R. Dental microwear texture analysis of extant African Bovidae. Mammalia 76, 157–174 (2012).

Haupt, R. J., DeSantis, L. R. G., Green, J. L. & Ungar, P. S. Dental microwear texture as a proxy for diet in xenarthrans. J. Mammal. 94, 856–866 (2013).

Hedberg, C. & DeSantis, L. R. G. Dental microwear texture analysis of extant koalas: clarifying causal agents of microwear. J. Zool. 301, 206–214 (2016).

Dunn, O. J. Multiple comparisons using rank sums. Am. Soc. Qual 6, 241–252 (1964).

Cabin, R. J. & Mitchell, R. J. To Bonferroni or not to Bonferroni: when and how are the questions. Bull. Ecol. Soc. Am. 81, 246–248 (2000).

Nakagawa, S. A farewell to Bonferroni: the problems of low statistical power and publication bias. Behav. Ecol 15, 1044–1045 (2004).

Scott, R. S., Teaford, M. F. & Ungar, P. S. Dental microwear texture and anthropoid diets. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 147, 551–579 (2012).

Acknowledgements

We thank curators and collections managers associated with all collections here mentioned for access to specimens, including the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH), the East Tennessee State University and General Shale Brick Natural History Museum and Visitor Center (ETMNH), the Field Museum of Natural History (FMNH), the Florida Museum of Natural History (FLMNH), the Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, Berkeley (MVZ), the Texas Memorial Museum (TMM), and the Yale Peabody Museum (YPM). We also thank M. Silcox and M. Teaford for helpful feedback on earlier versions of this manuscript. This work was supported by the National Science Foundation (EAR1053839 to L.R.G.D.), Vanderbilt University (L.R.G.D.), East Tennessee State University (B.W.S.), and the University of New England (A.C.S).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.R.G.D. conceived of the idea and designed the study; L.R.G.D., A.C.S., B.W.S., M.W.C. and S.C.W. contributed data and analytical tools; L.R.G.D. and A.C.S. performed research and analyzed data; L.R.G.D., A.C.S. and F.G. wrote the paper. All authors provided significant intellectual contributions, including editorial input on the manuscript. All authors gave final approval for the publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

DeSantis, L.R.G., Sharp, A.C., Schubert, B.W. et al. Clarifying relationships between cranial form and function in tapirs, with implications for the dietary ecology of early hominins. Sci Rep 10, 8809 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-65586-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-65586-w

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.