Abstract

The relationship between alcohol consumption and sleep disturbance is complex. The association of alcohol dependence with insomnia is likely to be bidirectional in nature. Alcohol use is common among older people in many societies and the prevalence of insomnia tends to increase with age, therefore this group warrants particular consideration. We explored the cross sectional and long term (30 years) associations between alcohol drinking (volume and hazardous drinking) and sleep duration and insomnia in a general population study of older adults (6,117 male and female civil servants followed for 30 years). For men, drinking more than 21 units (approximately 168 grams) of alcohol per week, compared with not drinking, was associated with waking several times a night (odds ratio 1.30, confidence intervals 1.02–1.66). Men who maintained a heavy volume of drinking over the three decades of observation, or who had an unstable consumption pattern, tended to have worse sleep profiles in terms of waking tired and waking several times. Sustained male hazardous drinking (as measured by the AUDIT-C scale) was also associated with worse sleep profiles. Findings for women were not so clear. In this population based setting, drinking high volumes of alcohol may contribute to the prevalence of sleep problems in older age, particularly for men. People in this age group should be discouraged from using alcohol as a sleep aid.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Inadequate sleep is estimated to affect about one in five adults1. Insomnia symptoms (short sleep and disturbed sleep) are associated with an increased risk of a range of chronic health conditions, such as diabetes2, hypertension3 and all-cause mortality4.

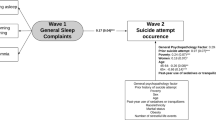

The relationship between alcohol consumption and sleep disturbance is complex. Alcohol acts as a sedative and reduces sleep onset latency5, and as such, may be used proactively to relieve insomnia6. However, there is evidence that alcohol consumption also disrupts sleep, particularly the period of rapid eye movement (REM) sleep7. The perpetual use of alcohol as a sleep aid may be a counterproductive long-term strategy as alcohol disrupts sleep quality and intensifies the need to consume more alcohol8. The association of alcohol dependence with insomnia may be bidirectional in nature9.

Heavy consumption of alcohol over an extended period of time leads to increased tolerance and this tolerance is accompanied by adaptation of the neurotransmitter systems5. Furthermore, long-term consequences of alcohol may lead to changes in sleep regulation. The influence of alcohol on sleep therefore needs to be evaluated by exploring both the short term effects on sleep (cross sectional data) and the long-term consequences (longitudinal data of repeated measures). At present, most literature is based on cross-sectional studies and thus cannot assess direction of effects6.

Alcohol consumption among the elderly has increased10 and the prevalence of insomnia tends to increase with age11, therefore this age group warrants particular consideration.

This paper will address the following aims: (1) to explore the cross-sectional association between alcohol drinking and sleep problems in a general population study of older adults and (2) to explore the long term association between typologies of alcohol drinking and chronic sleep problems. To our knowledge, this is the first paper to utilize individual longitudinal repeat data on sleep and alcohol in this way.

Methods

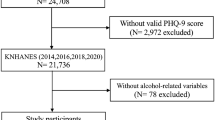

The Whitehall II study was established in 1985 as a longitudinal study to examine the socioeconomic gradient in health and disease among 10,308 civil servants (6895 men and 3413 women)12. All civil servants aged 35–55 years in 20 London-based departments were invited to participate by letter and 73% agreed. Baseline examination (Phase 1) took place during 1985–1988 and involved a clinical examination and a self-administered questionnaire containing sections on demographic characteristics, health, lifestyle factors, work characteristics, social support and life events. Subsequent phases of data collection have alternated between postal questionnaire alone and postal questionnaire accompanied by a clinical examination.

The University College London Medical School Committee on the ethics of human research approved the Whitehall II study all research was performed in accordance with relevant guidelines/regulations. Written informed consent was obtained at baseline and renewed at each contact. Whitehall II data, protocols, and other metadata are available to bona fide researchers for research purposes. (Data sharing policy is available at http://www.ucl.ac.uk/whitehallII/data-sharing).

During three decades of follow-up, repeated measures were obtained via a self-completed questionnaire of insomnia symptoms and sleep duration and repeated measures of alcohol consumption and problem drinking.

Assessment of Sleep measures

Sleep duration was assessed at phases 1 (1985–88), 5 (1997–99), 7 (2002–04, 9 (2007–09), and 11 (2012–13) by asking participants: “how many hours of sleep do you have on an average week night?” Respondent choices were: 5 hours or less, 6 hours, 7 hours, 8 hours, and 9 hours or more”.

Sleep disturbances were assessed at phases 5, 7, 9, and 11 using the 4-item Jenkins Scale13. This scale includes 4 questions on “having trouble falling asleep”, “waking up several times per night,” “having trouble staying asleep,” “waking up after the usual amount of sleep feeling tired and worn out” (i.e., waking without feeling refreshed) over past 30 days; all items have a 6-point response scale (1 = never; 2 = 1–3 days; 3 = 4–7 days; 4 = 8–14 days; 5 = 15–21 days; 6 = 22–30 days).

All sleep variables were dichotomized to form groups that were, as closely as possible, similar in size in relation to the total sample. These were as follows; Sleep duration (<7 versus 7+ hours (reference)), Trouble staying asleep over 30 days (4+ v. <4 days), Trouble falling asleep (1+ v. 0 days), Wake as usual but tired (1+ v. 0 days), Wake several times a night, (4+ v. <4 days). Dichotomization in this way allowed for a large enough sample to use in statistical analyses when stratifying by men and women. For all sleep variables the sleep category corresponding to better sleep was treated as the reference category.

Chronic sleep problems were defined as those when participants who reported a sleep problem (based on the above dichotomy) at three or more data collection phases over the follow-up period.

Assessment of alcohol consumption

Volume of consumption (phases 1, 3, 5, 7, 9, 11)

Participants were asked to report the number of alcoholic drinks they had consumed in the last 7 days. Drinks were converted into UK units of alcohol (whereby one unit is equivalent to 8 g of ethanol) using a conservative estimate of one UK unit for each measure of spirits and glass of wine, and two UK units for each pint of beer. These converted measurements were then summed to define the total weekly number of UK units consumed. Participants who did not drink alcohol in the past year were classified as ‘non-drinkers’.

Retrospective alcohol life-course grid

Life course alcohol consumption was defined using decade based grids14 (Appendix 1) starting with information in the teens (16–19 years) and spanning to the eighties (and older) on the three components of the AUDIT-C questionnaire: frequency of consumption, number of drinks on a typical drinking day, and frequency of consuming six or more drinks in a single occasion. AUDIT-C cases were defined as those scoring 5 or more points15. Non-drinkers (participants who did not drink alcohol in the previous year) were excluded from the classification (Appendix 2)

Alcohol typologies based on volume

Typologies of alcohol consumption over the measurement periods were then created16: (1) Stable None, (2) Stable moderate, (3) Stable heavy, (4) Unstable moderate (at least half of the phases were moderate), (5) Unstable heavy and (6) Former drinkers (previously reported consumption but none in the most recent phase). “Moderate” (within UK guidelines17 (1–14 [8–112 g] units per week), and “Heavy” (above guidelines (15 + units). When an individual reported moderate and heavy on an equal number of occasions, participants were assigned to the unstable heavy drinking group. There were 44 participants who did not fall into either of the categories and were excluded.

Hazardous drinking over follow-up

Participants were considered to be chronically hazardous drinkers if they were AUDIT-C positive on three of more data collection phases (in the retrospective alcohol life-course grid).

Analyses

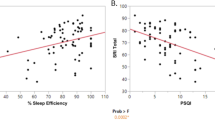

Cross-sectional associations were explored using phase 11 data. Longitudinal associations used data from phases 1 through to 11. Logistic regression analyses with the sleep variables as the outcome variable, and alcohol variables as the main exposure, were performed in Stata v15, adjusting for age. Models were carried out separately for the different alcohol measurements, and were stratified by men and women.

Results

In 2012–2013, 70.9% of the original cohort who were still alive (age range 61–81 years), participated in phase 11. Of these 6,318 men and women, 6117 (96.8%) had data on alcohol and sleep. Men consumed more alcohol than women with 15.7% consuming 21 or more units per week compared to only 2.4% of women (Table 1). 30.5% men and 12.8% women scored more than 5 on the AUDIT score, indicating hazardous drinking.

The most common drinking typologies over the three decades of observation were stable moderate drinkers (21.2%) and unstable moderate (29.2%). Women were more likely to report being former drinkers than men (24.8% and 12.8% respectively) (Table 2). Chronic hazardous drinking was indicated in 38% men and 17% women.

In terms of sleep problems, men were more likely to report sleeping less than 7 hours per night than women (63.7% men compared to 54.4% women). However, women were more likely to report trouble falling asleep (69.6% compared to 49.5% men) (Table 1). Over the thirty years follow up, women generally reported more chronic sleep problems than men (Table 2). More than half the women studied reported trouble falling asleep, waking tired, and/or waking several times a night.

Cross sectional analyses between alcohol (both volume and hazardous) and sleep problems found that men drinking more than 21 units per week or drinking hazardously were more likely to have disturbed sleep parameters than those not drinking in the past week or not drinking hazardously (Table 3). For example, men drinking 21+ units were more likely to wake several times a night than non-drinkers (OR 1.30 CI:1.02–1.66). For women, the picture is less clear. There is a suggestion that those women drinking more than 21 units were less likely to have short sleep (less than 7 hours) compared to non-drinkers (OR 0.39 CI: 0.19–0.81).

The relationship between longitudinal alcohol typologies and chronic sleep problems reflected the cross-sectional picture (Table 4). For men, compared to stable moderate drinkers, those who were stable heavy drinkers were more likely to wake tired (RRR 1.37 CI: 1.02–1.84) and wake several times a night (RRR 1.52 CI: 1.13–2.05). For women there were less clear risks associated between drinking and sleep problems.

Discussion

In this large, population based study of older adults, we found that, for men, drinking more than 21 units per week, compared with not drinking, was associated with disturbed sleep (cross sectional analyses). Those who maintained this heavy volume of drinking over the three decades of observation, or who drank in a potentially hazardous pattern tended to have worse sleep profiles in terms waking tired and waking several times. The findings were not so clear among women and the reasons for sex differences warrants further research.

In a recent cross-sectional population study of 187,950 adults in the United States short sleep prevalence was higher among adults who consumed any alcohol compared with those who never consume alcohol18. Our findings contrast with this study in that we did not find strong association between drinking and sleep duration. The disparity may, in part, be due to ethnic differences. Jackson et al. note that the prevalence of short sleep across alcohol consumption patterns was more variable among whites, and the majority of Whitehall II participants are white.

There are few other longitudinal population based studies with which to compare our findings. Most are based on alcoholics in clinic settings19. Among 1,920 community dwelling men and women, those with persistent alcohol dependence had higher odds of insomnia that those without alcohol dependence over a fifteen year follow-up20. Whilst we did not measure alcohol dependence, we did find such an association between hazardous drinking and disturbed sleep in our data.

Our finding that those who have trouble falling asleep were more likely to be persistent heavy drinking suggests that they may be using alcohol as a sedative. This is partially corroborated in an earlier study on same population. The Whitehall II participants were asked about reasons for change in drinking over the last 10 years and an increase in consumption was cited as a means to help get to sleep was by 6% of men and 5% of women21.

Our study has limitations. For instance, we used self-reported alcohol consumption data and self-reported sleep data and therefore these measures may be at risk of reporting bias. The population may not be representative of all older adults in the UK and it is unlikely that the full spectrum of drinking behavior is represented. However, the mean consumption is similar to that reported in representative studies, such as Health Survey for England and English Longitudinal study of Ageing22. Another limitation is that we were not able to capture fully patterns of consumption in terms of binging. Drinking appears to have differential effects on sleep depending on chronic versus acute dosage18 Our cut-offs for drinking exposures and sleep problems are largely arbitrary and it is possible to other subtle relationships are masked. Findings using self-reported sleep can only support the hypothesis that alcohol impacts on underlying sleep architecture (for example reduction or suppression of REM sleep), which would need to be confirmed by overnight polysomnography sleep studies. Despite these limitations, this study has important strengths. The repeated collection of alcohol and sleep data over such a long period is unique. We were thus able to look at long-term drinking typologies and persistent sleep problems over three decades.

Conclusion

In this population based setting, drinking high volumes of alcohol or drinking hazardously may contribute to the prevalence of sleep problems in older age. Those with disrupted sleep should consider reducing alcohol consumption and people in this age group, particularly men, should be discouraged from using alcohol as a sleep aid. It is well recognized that sleep problems have a significant impact on quality of life with increased morbidity and mortality seen in population studies3. Identifying people at risk of sleep disturbances as a result of their drinking may have important public health benefits.

References

Krueger, P. M. & Friedman, E. M. Sleep duration in the United States: a cross-sectional population-based study. Am J Epi. 169, 1052–1063 (2009).

Shan, Z. et al. Sleep duration and risk of type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. Diabetes Care 38, 529–37 (2015).

Cappuccio, F. P., D’Elia, I., Strazzullo, P. & Miller, M. A. Sleep duration and all-cause mortality. A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Sleep 33, 585–592 (2010).

Palagini, L., Bruno, R. M., Gemignani, A., Ghiadoni, L. & Riemann, D. Sleep loss and hypertension: a systematic review. Curr Pharm Des. 19, 2409–19 (2013).

Colrain, I. M., Nicholas, C. L. & Baker, F. C. Alcohol and sleeping brain. Handb Clin Neurol. 125, 415–431 (2014).

Ebrahim, I. O., Shaprio, C. M., Williams, A. J. & Fenwick, P. B. Alcohol and Sleep I: Effects on normal sleep. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 37, 539–49 (2013).

Roehrs, T., Papineau, K., Rosenthal, L. & Roth, T. Ethanol as a hypnotic in insomniacs: Self administration and effects on sleep and mood. Neuropsychopharmacology 20, 279–286 (1999).

Stein, D. & Friedmann, P. D. Disturbed sleep and its relationship to alcohol use. Subs. Abuse 26, 1–13 (2005).

Chakravorty, S., Chaudhary, N. S. & Brower, K. J. Alcohol dependence and its relationship with insomnia and other sleep disorders. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 40, 2271–2282 (2016).

Crome, I. B., Rao, T., Tarbuck, A., Dar, K. & Janikiewicz, S. Royal College of Psychiatrists. Our Invisible Addicts: Council Report 165. (Royal College of Psychiatrists, London, 2011).

Foley, D. J. et al. Sleep complaints among elderly persons: an epidemiologic study of three communities. Sleep. 18, 425–32 (1995).

Marmot, M. & Brunner, E. Cohort Profile: Whitehall II. Int J Epidemiol. 34, 251–6 (2005).

Jenkins, C. D., Stanton, B. A., Niemcryk, S. J. & Rose, R. M. A scale for the estimation of sleep problems in clinical research. J Clin Epidemiol. 41, 313–21 (1988).

Bell, S. & Britton, A. Reliability of a retrospective decade-based life-course alcohol consumption questionnaire administered in later life. Addiction 110, 1563–73 (2015).

Dawson, D. A., Grant, B. F., Stinson, F. S. & Zhou, Y. Effectiveness of the Derived Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT‐C) in Screening for Alcohol Use Disorders and Risk Drinking in the US General Population. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 29, 844–54 (2005).

Britton, A. et al. Twenty-year trajectories of alcohol consumption during midlife and atherosclerotic thickening in early old age: findings from two British population cohort studies. BMC Medicine 14(1), 111, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-016-0656-9 (2016).

UK Chief Medical Officers’ Low Risk drinking guidelines 2016 UK Departments of Health (2016)

Jackson, C.L., Gaston, S.A., Liu, R., Mukamal, K., Rimm, E. The relationship between alcohol drinking patterns and sleep duration among black and white men and women in the United States. Int J of Environl Res Pub Health, 15, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15030557 (2018).

Bower, K. J. Alcohol’s effects on sleep in alcoholics. Alcohol Res Health 25, 110–135 (2001).

Crum, R. M., Ford, D. E., Storr, C. L. & Chen, Y.-F. Association of sleep disturbance with chronicity and remission of alcohol dependence: data from a population-based prospective study. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research 28, 1533–1540 (2004).

Britton, A. & Bell, S. Reasons why people change their alcohol consumption in later life: findings from the Whitehall II Cohort Study. PloS One 10, e0119421 (2015).

Britton, A., Ben-Shlomo, Y., Benzeval, M., Kuh, D., Bell, S. Life-course trajectories of alcohol consumption in the UK using longitudinal data from nine cohort studies. BMC Medicine 13: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-015-0273-z (2015).

Acknowledgements

The Whitehall II study is supported by the UK Medical Research Council (MR/K013351/1; G0902037), BritishHeart Foundation (RG/13/2/30098), and the US National Institutes of Health (R01HL36310; R01AG013196).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.B. and A.N. conceived the idea. L.N.F. did all the analyses. A.B. wrote the main text and all authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Britton, A., Fat, L.N. & Neligan, A. The association between alcohol consumption and sleep disorders among older people in the general population. Sci Rep 10, 5275 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-62227-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-62227-0

This article is cited by

-

Association between alcohol consumption and sleep traits: observational and mendelian randomization studies in the UK biobank

Molecular Psychiatry (2024)

-

An Overview of Sex and Gender Considerations in Sleep and Alcohol Use

Current Addiction Reports (2024)

-

Changes in Restless Sleep, Self-Control, and Alcohol-Related Problems with Police from Late Adolescence to Adulthood

Journal of Youth and Adolescence (2024)

-

Sleep duration, hypnotic drug use, and risk factors: cross- sectional study

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

The Effects of Cigarette Smoking, Alcohol Consumption, and Use of Both Cigarettes and Alcohol on Chinese Older Adults’ Sleep: Results from a Longitudinal Study

International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction (2023)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.