Abstract

Presently, there is growing concern worldwide regarding the adulteration of meat products. However, no reports on determining meat authenticity have been reported in China. To verify labelling compliance and evaluate the existence of fraudulent practices, 250 sausage samples were purchased from local markets in Sichuan Province and analysed for the presence of chicken, pork, beef, duck and genetically modified soybean DNA using real-time and end-point PCR methods, providing a Chinese case study on the problem of world food safety. In total, 74.4% (186) of the samples were properly labelled, while the other 25.6% (64) were potentially adulterated samples, which involved three illicit practices: product removal, addition and substitution. The most common mislabelling was the illegal addition of, or contamination with, duck. Therefore, meat authenticity monitoring should be routinely conducted. Additionally, the strict implementation of the nation’s food safety laws, along with regular surveillance, should be compulsory to alleviate and deter meat adulteration.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The meats of swine, cattle, sheep and poultry are currently consumed by people in many countries, including China, as main sources of animal protein1. Currently, China is the largest producer of meat in the world2,3, even though the quantity of meat consumed per capita per year in China is not the greatest. With the increase in consumer incomes in China, the structure and quantity of meat consumption have changed greatly in recent years. In 2014, the consumed quantities of swine, both cattle and sheep, and poultry meat per capita in China were 20, 1.6 and 8 kg4, respectively. When compared with the values in 2000 in China, the consumption per capita of swine and poultry meat increased by 37.65% and 113%, respectively, while that of cattle and sheep fell 17.1%4. In general, meat consumption per capita has grown in China over the past 30 years. Significantly, the quantity of porcine meat consumed is decreasing, while the consumption of cattle, sheep and poultry is increasing steadily. Currently, the quantity of meat consumed in China is at a moderate level compared with other countries. The characteristics of meat consumption in China are similar to those of Hong Kong, Taiwan and Japan, which are different from those of the USA5.

Sichuan Province in southwest China is located in the upper reaches of the Yangtze River. With Chengdu as the capital city, Sichuan covers an area of over 486,000 km2 and ranks fifth in China in terms of area, having jurisdiction over 21 cities (states) and 183 counties (county-level cities and districts). Sichuan has a population of ~82.26 million, of which 100,000 are members of the Hui Muslim minority. The members of the Muslim Hui community are distributed in all the counties of Sichuan Province, but mainly in Chengdu (CD), Aba (AB), Mianyang (MY) and Xichang (XC) cities6. The Hui Muslim minority follows strict dietary laws enshrined in the holy Quran. Under their religious rules, Hui Muslim people are forbidden to eat pork, and therefore, its consumption must be avoided. In 2015, the meat consumption per capita in Sichuan was the highest in China, with a value of 39.3 kg5.

With the exposure of the horse meat scandal in Europe, modern consumers are increasingly health conscious and are demanding more comprehensive information on the origin, composition and safety of the foods they consume7,8,9, and the authenticity of halal foods has also attracted the attention of the Hui Muslim people. Now, the authenticity determination of meat products in the Middle East and other Islamic countries, especially in East Asia, is mandatory10 owing to fraudulent practices, such as adulteration, substitution and mislabelling, in the production of meat-containing products. However, the Department of Supervision and Administration for Food Safety in China currently focuses on the “safety” aspects of meat products, including the presence of veterinary drug residues, pathogenic microorganisms, heavy metals and chemical additives exceeding the regulatory limits, while the authenticity of meat products is not emphasised.

Authenticity is a paramount important criterion for food safety and quality. However, the identities of the ingredients in processed or composite mixtures are not always readily apparent11. Recent food scares, frauds and malpractices carried out by some food producers have increased public interest in the composition of food products owing to religious reasons and food allergies12. Consumers have the right to know what is in the food they are eating, and producers have a duty to inform and not knowingly mislead consumers regarding the sources or contents of their food products13. Food fraud is defined as “the deliberate and intentional substitution, addition, tampering, or misrepresentation of food, food ingredients, or food packaging; or false or misleading statements made about a product, for economic gain”, and it greatly affects food safety and public health14,15. Three common categories of food fraud are replacement, addition and removal. Among these, substitution is the most common, followed by addition14. Among foods, processed meat products, like ham sausages, are particularly vulnerable to adulteration because minced meat production removes the morphological characteristics of muscle, making it difficult to identify the origin16. Therefore, ham sausage can be illegally adulterated, substituted and added to in many ways during the production and distribution chains. Chinese ham sausage is a complex mixture, consisting mainly of meat and starch, as well as low concentrations of water, vegetable oil, salt, monosodium glutamate and other food additives. Additionally, chicken, duck and goose meats are cheap and widely available in Chinese markets. Consequently, to enhance profits, these cheaper meats are commonly adulterated into ham sausage16. Pork, which cannot be consumed under Muslim and Jewish dietary restrictions, is the most commonly substituted meat in South Africa17. At present no studies on meat substitution in the Sichuan market of China have been reported. Therefore, there is a need to investigate meat species to verify that the products are in compliance with the label statements and regulations in force, and to support fair trade and protect consumer rights18.

By 2016, China had approved 60 genetically modified (GM) crop events for food and feed use19. Of the GM soybean events, GTS40-3-2, MON89788 and A2704-12 are the most imported transgenic soybean lines in China20. Soybean powder is commonly added to ham sausage as a raw material because its addition makes the structure of the sausage tight and elastic, as well as rendering the cut surface smooth. Thus, it improves the overall quality of sausage products21. According to the administrative regulations on the safety of GM organisms in China, the labelling of GM products or food is mandatory. Several studies worldwide have found different degrees of species adulteration in meat products17,22,23,24,25,26,27 but no similar studies in China have been published. Therefore, there is currently a lack of information on adulterated meat products. Owing to the stability of DNA, most analytical methods used to date for meat authentication have relied on the detection of species-specific DNA28, and various PCR-based studies have been suggested by researchers29. In the past decade, PCR methods, such as end-point and real-time PCR, have been widely used to detect adulterated meat products30,31,32,33,34. To verify labelling compliance and evaluate the existence of fraudulent practices, 250 ham sausage samples were purchased from local markets in 21 cities of Sichuan Province, and they were, for the first time, analysed for the presence of chicken, swine, cattle, duck and GM soybean DNA using real-time and end-point PCR methods. The aims of this study were to detect the presence of species substitutions, undeclared species, species cross-contamination and GM ingredients in ham sausages, to investigate the incidence of mislabelling in ham sausages sold in Sichuan, China and to assess the impacts of such practices on consumer confidence and fair trade.

Materials and Methods

Sample materials

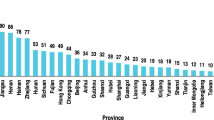

A total of 250 sausage products, representing a variety of meat origins (pork, chicken, duck, beef or mixtures) were purchased, between July and August 2016, from 77 local markets and 89 restaurants across 21 counties in Sichuan Province (Fig. 1). These samples represented six different types of meat or meat mixtures, including products labelled as containing chicken (n = 16; Type I) and mixtures of chicken and duck (n = 47; Type II), chicken and pork (n = 156; Type III), chicken, duck and pork (n = 29; Type IV), chicken, pork and beef (n = 1; Type V), and chicken, duck and beef (n = 1; Type VI). Sample details are shown in Table 1. Manufacturer names are not disclosed. All the samples were frozen and maintained at 4 °C in our laboratory. The authentic meat samples (reference samples) of swine, chicken, duck and cattle used as positive controls were purchased from the Chinese Academy of Inspection and Quarantine (Beijing, China). The reference materials for GM soybean GTS40-3-2 were purchased from the Institute for Reference Materials and Measurements in Geel, Belgium, and the reference DNAs for GM soybean A2704-12 and MON89788 were purchased from the American Oil Chemists Society (Champaign-Urbana, IL, USA).

Geographical distribution of markets from which the sampled sausage products were purchased for this study. Locality codes correspond to the city names in Table 1.

DNA extraction

Genomic DNAs were isolated and purified from the reference materials and test samples, and sterilised ultrapure water was used as a negative control (blank) for DNA extraction using a genomic DNA purification kit (Tiangen Biotech Co., Ltd., Beijing, China) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The DNA concentrations were measured using a NanoDrop ND-1000 UV Spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham City, MA, USA).

Primers and PCR conditions

Species-specific DNA segments for duck, pork and beef, and the 18S rRNA of eukaryotes (control for species DNA) were amplified using primer and probe sequences as described in the Inspection and Quarantine Industry Standard of the People’s Republic of China35,36 and the National Standard of the People’s Republic of China37 (Table 2). DNA species-specific fragments of duck, pork and beef, as well as the 18S rRNA of eukaryotes, in samples and reference materials were amplified using real-time PCR on an ABI 7500 fluorometric thermal cycler (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA), with simultaneous amplification of the blank from the DNA extraction and non-template PCR control. All the samples were tested for the presence of duck-, pork- and beef-specific DNA fragments. The real-time PCR assays were carried out in a final volume of 25 µL containing 1× THUNDERBIRD™ Probe qPCR Mix (Toyobo Co., Ltd., Osaka, Japan), 1× ROX reference dye, 500 nM each primer, 250 nM probe and approximately 50–100 ng genomic DNA per sample or reference material (control) as the template35,36,37. The thermocycling settings for beef were as follows: initial incubation at 95 °C for 10 min and then 45 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s and 60 °C (annealing and extension, respectively) for 1 min. Fluorescence measurements were taken after annealing and extension. For the thermal amplification programs of pork and duck, the annealing temperature was set to 58 °C for 15 s, and all other program parameters were the same as those for beef.

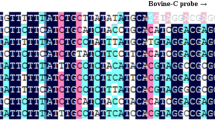

The sequences of primer pairs for the amplification of chicken, the three GM soybean events (GTS40-3-2, A2704-12 and MON89788) and the endogenous Lectin gene (soybean taxon-specific gene used as a control for soybean DNA) were from data in the Inspection and Quarantine Industry Standard of the People’s Republic of China38 and the Agricultural Industry Standard of the People’s Republic of China39,40,41. All of the primers and probes (Table 2) were synthesised by Sangon Biotechnology Co, Ltd. (Shanghai, China). All of the end-point PCR (conventional PCR) reactions were carried out in an ABI Veriti 96 thermal cycler (Applied Biosystems) with a 25-µL reaction volume, containing approximately 50 ng of genomic DNA, 1× QuickTaq® HS DyeMix (Toyobo Co., Ltd.) and 400 nM of each primer38,39,40,41. The amplification of the blank for DNA extraction and non-template PCR control were performed simultaneously with the same primers to determine whether contamination occurred during DNA extraction and PCR set up. The thermocycling program of the conventional PCR assays for the Lectin gene and two GM soybean lines, GTS-40-3-2 and A2704-12, were as follows: initial denaturation for 5 min at 95 °C; 35 cycles of amplification for 30 s at 94 °C, 30 s at 58 °C and 30 s at 72 °C; and a final extension for 7 min at 72 °C. The annealing temperatures of amplification for the MON89788 line and chicken species-specific DNA were 56 °C and 63 °C, respectively. Except for the annealing temperatures, the other program parameters were the same as those of the GM soybean lines GTS-40-3-2 and A2704-12. As indicated by the standards35,36,37,38,39,40,41, the specificity of the methods described was highly specific, and the limit of detection was 0.1%. The specificity (high specificity) and sensitivity (five copies) levels of the conventional and real-time PCR methods used to analyse the sausage samples were not evaluated in this study because they have been previously confirmed as the national standards for GM organism detection in China. PCR products were analysed by 2.5% agarose gel electrophoresis containing ethidium bromide in 1× Tris-acetate EDTA buffer for 20 min at 110 V.

Results

There were no targeted DNA bands or amplification signals in the PCR of the blank controls, and the expected DNA bands or amplification signals were obtained in the PCR of the positive controls. In total, 250 sausage samples collected in 166 local markets or restaurants in 21 cities in Sichuan Province, China were first identified using PCR methods. DNA fragments of the 18S rRNA and/or Lectin gene were amplified successfully from templates isolated from all the samples, indicating the efficient extraction of genomic DNA from eukaryotes (meat species) and soybean (plant addition to sausage), which can be used in the subsequent analyses. Among the samples, the mislabelling of 64 products (25.6%) was found. Mislabelled samples collected from 17 cities, except for sausage samples purchased from LZ, BZ, ZY and ZG, were determined (Table 1). The greatest frequency (75.0%) of mislabelling was observed in PZH, and the lowest frequencies (8.3%) were detected in SN, MS and NC. Although most of the sausage products sampled were from the capital city of Sichuan Province (CD), the frequency of mislabelled samples was less than 19%. Surprisingly, the three highly imported GM soybean lines, GTS40-3-2, MON89788 and A2740-12, were not detected in any sample labelled as containing soybean.

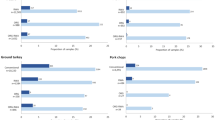

Among the 64 mislabelled samples, one sample labelled as Type III (containing chicken and pork) tested positive for chicken and duck (Type II; Table 3), representing a typical meat species substitution. Three samples labelled as Type I (containing chicken, duck and pork), tested negative for duck (Type III; Table 3). Additionally, a high incidence of illegal additions or contamination of undeclared meat species was observed in 60 samples. Duck meat was the most common undeclared animal species found in 58 samples, while unclaimed pork was detected in the 2 samples labelled as Types II and VI. The greatest incidences (75%) of illegal additions of, or contamination with, undeclared duck species were found in PZH and GY, followed by 60% in KD and 41.7% in DZ and NJ.

Illegal additions or cross-contamination of undeclared duck meat were detected in 25% of Type I samples, with Ct values that ranged between 22.87 and 35.18. In addition, unclaimed pork was detected in Type II samples, with the lowest prevalence rate (2.1%). Additionally, duck meat was substituted for pork in one sample labelled as Type III. However, the presence of undeclared duck DNA was prevalent (34.6%) in the Type III sample group, with the Ct values for duck DNA being in the range of 20.75–35.47. Of all the Ct values for unclaimed duck, there were 31 Ct values of less than 27, and 25 Ct values that varied between 30 and 35. On the contrary, declared duck was not detected in 10.3% of Type IV samples. The Type V sample was correctly labelled. As in Type II, the illegal addition or contamination of undeclared pork meat existed in Type VI, with a Ct of 25.74 (Table 4).

Discussion

Here, for the first time, the meat authenticity of ham sausages produced in China was investigated to assess the extent of mislabelling in sausage products using two types of detection methods based on PCR. In total, 74.4% of the samples were properly labelled, with the contents corresponding to the product lists. However, 25.6% of the potentially adulterated samples were subject to one of three illicit practices, removal (declared species not detected in the product), addition and substitution with another species. The percentage of mislabelling (25.6%) in this work was relatively small compared with those discovered in American (38.5%)42 and Malaysian (78.3%)43 markets. However, the percentage of mislabelling (25.6%) was greater than that reported in Canadian markets (20%)26. The most common mislabelling in this study was contamination with, or the illegal addition of, duck.

Altogether, 58 samples were found to contain undeclared duck as determined by real-time PCR, with Ct values ranging from 20.75 to 35.47. However, it was difficult to determine whether duck meat was intentionally added to the 58 samples or these samples were illegally contaminated with duck meat because Ct values are affected by many factors (i.e., inhibitory ingredients in the samples and the level of DNA degradation). Similarly, two samples containing unstated pork had low Ct values of 25.74 and 26.79, which indicated illegal additions or cross-contamination. In the sausage production chain, cross-contamination can arise when improperly cleaned (or uncleaned) equipment is used to process meat from more than one species44. Perhaps, a quantitative PCR analysis will aid in determining whether undeclared ingredients are additives or contaminants. Compared with the illegal additives in sausage products reported in previous studies17,22,23,24, in China, the prevalent unlabelled additive to sausage was duck, while in other countries chicken was the major unlabelled additive. Generally, the average price of duck is low in China, while beef is the highest, followed by pork and chicken. Therefore, duck is an economical additive for manufacturers to decrease the production cost of sausages. The different prices of meats worldwide explained why the illegal meat species used as additives differ between the sausages produced in China and those in other countries. They also explained the substitution of duck for pork in the test samples. However, the more expensive pork was added to two samples labelled as Types II and VI, and they had pork-associated Ct values of less than 30. Accordingly, the presence of pork did not seem to be the result of cross-contamination events. Similarly, it is hard to understand why the declared duck was not detected in three samples marketed as Type IV. It may be that the two aforementioned cases were mislabelled as human errors.

Another main reason for performing a survey on the meat authentication of sausage is because of religious concerns. Of the 250 sausage samples, two were clearly listed as meeting Muslim dietary laws (Halal) on their labels. One tested positive for undeclared duck, while the other was correctly labelled. Fortunately, the pork prohibited by Halal was not detected. China is a multiracial country, with a Muslim minority population of more than 10 million. It is estimated that more than 100,000 Hui people live in Sichuan Province, China. The mislabelling of sausage products may lead to the violation of personal or religious beliefs. A previous study reported that pork is the most common meat substitute, and its consumption breaches Muslim dietary restrictions17. Unfortunately, pork was found in sausages and ground-meat products in previous investigations10,17. Although pork was not found in the Halal sausages tested in this study, the detection of meat origins for Halal products should not be neglected in the future.

China has imported large quantities of GM soybeans since 2000. However, the three most imported GM soybean lines (GTS40-3-2, MON89788 and A2704-12) were not detected in any of the sausage samples, as in highly processed foods in previous reports45,46. It is challenging to extract and amplify total DNA from heavily processed products (especially fermentation products) because of the degradation of genomic DNA. Thus, the exogenous DNA of GM soybean in the samples tested may have degraded during fermentation; therefore, the targeted DNA segments (flanking DNA fragments) were not amplified46.

The observations of illegal additions, removals and substitutions in sausages in this study were similar to those of previous research17,22,23,24. Because of the high market value of meat compared with most plant-derived products, meat products are often targets for adulteration17. The sausage production technique often leads to changes in the appearance, colour, texture and flavour of the meat; therefore, additions, removals and substitutions are easily masked47. Thus, it is very difficult to visually detect these illicit events during meat processing. Consequently, adulterations are commonly found in sausage and ground meat products17,22,23,24.

The accurate identification of ground-meat products, including sausages, in markets is a growing concern because of the high incidence of adulteration worldwide. This study revealed that the mislabelling of sausages owing to illegal additions, substitutions and removals is a reality in China, and that local consumers are undoubtedly encountering undeclared animal species in sausage products. Our results provide a baseline for the preliminary assessment of meat species’ mislabelling in sausage products in China. Owing to recent food fraud scandals, including the intentional contaminating of infant milk formula with melamine48,49,50, food safety in China currently focuses on identifying the presence of poisonous chemical substances in foods. The food control authorities in China are not routinely monitoring sausage and ground-meat products for mislabelling. To date, the authentication of meat species in meat products has not been conducted across China. Although the mislabelling resulting from additions, substitutions of undeclared meat species and the removal of declared meat species may not impact food safety and public health, consumers can be deceived regarding the products they are purchasing and consuming51. Presently, according to our research, the fraudulent mislabelling of the additional of duck to sausages is becoming an important problem in the meat industry. The meat industry in China will face a crisis in consumer confidence if the adulteration of sausages becomes generalised. Identifying the species’ origins in sausages and meat products is important for preventing adulteration and for protecting consumers’ health and religious convictions23.

In China, the adulteration and misbranding of meat products are prohibited by the related food safety laws. Despite the implementation of more stringent food labelling regulations locally and globally, the adulteration or misrepresentation of food products for illicit financial gain continues to be a common societal problem52,53. Accordingly, public safety measures and testing procedures should be implemented by regulatory agencies based on the declared products’ contents. This is an ongoing issue that urgently requires monitoring. This survey highlights the importance of increasing national concerns and government efforts in food traceability. The strict implementation of the food safety laws of the People’s Republic of China, along with regular surveillance and monitoring programs, are required to alleviate and deter mislabelling issues. Additionally, regular audits of processed meat plants by the regulatory agencies should be implemented to ensure that manufacturing operations comply with Chinese food regulations. While this investigation suggests the occurrence of the addition of undeclared meat species in sausage products, further studies are needed to detect the extent of mislabelling and to identify points in the production chain where mislabelling occurs. Future areas of work also include the expansion of the tested meat species, the ground meat products and the sampling sites across China.

Conclusions

Although several regulations and laws related to food and agricultural products are enforced in China, there is still a lack of information on the authentication of meat species. This study found a relatively low incidence (25.6%) of mislabelling owing to the adulteration of sausage products on the commercial market compared with previous reports17,22,23,24. Nevertheless, further studies are needed to determine the extent of adulteration across the whole meat industry in China, which would provide the government with more comprehensive data to be used in decision-making related to controlling the quality and safety of meat products.

Data availability

The datasets generated or analysed during the current study have been provided in this manuscript.

References

Hasiner, E. & Yu, X. H. Meat consumption and democratic governance: A cross-national analysis. China Econ Rev 3, 1–13 (2016).

Zhu, Z. Q. & Yi, F. H. Meat competitiveness in China: the gap with major exporting countries and causes. Prod Res 20, 96–110 (2007).

Sun, Z. Study on partial equilibrium model of China meat. Postdoctoral dissertation: Chinese academy of agricultural science, Beijing (in Chinese) (2016).

Cui, C. & Wang, M. L. China’s Meat Consumption Development and Its Prospect. Agric Outlook 10, 74–80 (2016).

Gao, Q. Meat consumption characteristics and influence factors of urban and rural residents in China. Master dissertation: Chinese academy of agricultural science, Beijing (in Chinese) (2013).

Zhang, Z. H. The history and current status of the Hui Muslim Minority in Sichuan. J Muslim Min Stud 2, 11–18 (1992).

Grunert, K. G. Current issues in the understanding of consumer food choice. Trends Food Sci Tech 13, 275–285 (2002).

Taljaard, P. R., Jooste, A. & Asfaha, T. A. Towards a broader understanding of South African consumer spending on meat. Agrekon 45, 214–224 (2006).

Verbeke, W. & Ward, R. D. Consumer interest in information cues denoting quality, traceability and origin: an application of ordered probit models to beef labels. Food Qual Prefer 17, 453–467 (2006).

Nakyinsige, K., Man, Y. B. C. & Sazili, A. Q. Halal authenticity issues in meat and meat products. Meat Sci 91, 207–214 (2012).

Xu, L., Cai, C. B., Cui, F., Ye, Z. H. & Yu, X. P. Rapid discrimination of pork in Halal and non-Halal Chinese ham sausages by Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy and chemometrics. Meat Sci 92, 506–510 (2012).

Teletchea, F., Maudet, C. & Hanni, C. Food and forensic molecular identification: update and challenges. Trends Biotechnol 7, 359–366 (2005).

Ortea, I., O’Connor, G. & Maquet, A. Review on proteomics for food authentication. J Proteomics 147, 212–225 (2016).

Moore, J. C., Spink, J. & Lipp, M. Development and application of a database on food ingredient fraud and economically motivated adulteration from 1980–2010. J Food Sci 77, 118–126 (2012).

Spink, J. & Moyer, D. C. Understanding and combating food fraud. Food Tech 1, 30 (2013).

He, W. L., Huang, M. & Zhang, C. Recent technological advances for identification of meat species in food products. Food Sci 3, 304–307 (2012).

Cawthorn, D. M., Steinman, H. A. & Hoffman, L. C. A high incidence of species substitution and mislabelling detected in meat products sold in South Africa. Food Control 32, 440–449 (2013).

Sakaridis, I., Ganopoulos, I., Argiriou, A. & Tsaftaris, A. A fast and accurate method for controlling the correct labelling of products containing buffalo meat using High Resolution Melting (HRM) analysis. Meat Sci 94, 84–88 (2013).

International Service for the Acquisition of Agri-biotech Applications (ISAAA). Global Status of Commercialized Biotech/GM Crops: 2016. ISAAA Brief No. 52. ISAAA: Ithaca, NY (2016).

Song, J., Song, Q. C., Wang, D. & Zhang, F. L. Monitoring the prevalence of genetically modified soybeans in tofu in Chengdu, China using real-time and conventional PCR. J food compos Anal 67, 172–177 (2018).

Wang, P. P., Pan, D. D., Sun, Y. Y., Cao, J. X., Zhao, P. F. Fermentation process optimizing and oxidation resistance of fermented duck sausage. Sci Technol Food Ind 8, 178–182 (2015). (in Chinese)6

Stamatis, C. et al. What do we think we eat? Single tracing method across foodstuff of animal origin found in Greek market. Food Res Int 69, 151–155 (2015).

Mousavi, S. M. et al. Applicability of species-specific polymerase chain reaction for fraud identification in raw ground meat commercially sold in Iran. J Food Compos Anal 40, 47–51 (2015).

Ulca, P., Balta, H., Çağın, I. & Senyuva, H. Z. Meat species identification and Halal authentication using PCR analysis of raw and cooked traditional Turkish foods. Meat Sci 94, 280–284 (2013).

Kane, D. E. & Hellberg, R. S. Identification of species in ground meat products sold on the U.S. commercial market using DNA-based methods. Food Control 59, 158–163 (2016).

Naaum, A. M. et al. Complementary molecular methods detect undeclared species in sausage products at retail markets in Canada. Food Control 84, 339–344 (2018).

Shehata, H. R. et al. Re-visiting the occurrence of undeclared species in sausage products sold in Canada. Food Res Int 122, 593–598 (2019).

Ballin, N. Z., Vogensen, F. K. & Karlsson, A. H. Species determination-can we detect and quantify meat adulteration? Meat Sci 83, 165–174 (2009).

Yang, L. X. et al. Identification of pork in meat products using real-time loop-mediated isothermal amplification. Biotechnol Biotec Eq. 5, 882–888 (2014).

Li, T. T. et al. Detection of goat meat adulteration by real-time PCR based on a reference primer. Food Chem 277, 554–557 (2019).

Meira, L. et al. EvaGreen real-time PCR to determine horse meat adulteration in processed foods. LWT - Food Sci Technol 75, 408–416 (2017).

Safdar, M., Junejo, Y., Arman, K. & Abasıyanık, M. F. A highly sensitive and specific tetraplex PCR assay for soybean, poultry, horse and pork species identification in sausages: Development and validation. Meat Sci 98, 296–300 (2014).

Druml, B., Mayer, W., Cichna-Markl, M. & Hochegger, R. Development and validation of a TaqMan real-time PCR assay for the identification and quantification of roe deer (Capreolus capreolus) in food to detect food adulteration. Food Chem 178, 319–326 (2015).

Pegels, N., Garcia, T., Martin, R. & Gonzalez, I. Market analysis of food and feed products for detection of horse DNA by a TaqMan real-time PCR. Food Anal Method 8, 489–498 (2015).

Yu, F. Q. et al. Determination of poultry derived materials in feedstuff-Real-time fluorescent PCR method, SN/T 2727-2010 (National Standard Number), Inspection and quarantine Industry Standard of the People’s Republic of China. Beijing, China: State Administration for Market Regulation of People’s Republic of China (2010).

Gao, H. W. et al. Identification of domestic animal ingredient in food and feed-Part 8: Detection of pig ingredient-Real-time PCR method, SN/T 3730.8-2013 (National Standard Number), Inspection and quarantine Industry Standard of the People’s Republic of China. Beijing, China: State Administration for Market Regulation of People’s Republic of China (2013).

Chen, Y. et al. Protocol of identification of bovine, caprine, ovine and porcine derived materials in gelatin-Real time PCR method, GB/T 25165-2010 (National Standard Number), Standard of People’s Republic of China. Beijing, China: State Administration for Market Regulation of People’s Republic of China (2010).

Zong H., Cao, C. F., Zhang, C. H. PCR method for the detection of chicken components in animal derived products, SN/T 2978-2011 (National Standard Number), Inspection and quarantine Industry Standard of the People’s Republic of China. Beijing, China: State Administration for Market Regulation of People’s Republic of China (2011).

Liu, Y. et al. Detection of genetically modified plants and derived products: Qualitative PCR method for herbicide-tolerant soybean GTS 40-3-2 and its derivates. Bulletin No. 1861-2-201 of Ministry of Agriculture of the People’s Republic of China. Beijing, China: Ministry of Agriculture of People’s Republic of China (2012).

Yang, J. B., Shen, P., Wang, X. F., Yang, L. T., Song, G. W. Detection of genetically modified plants and derived products: Qualitative PCR method for herbicide-tolerant soybean A2704-12 and its derivates. Bulletin No. 1485-7-2010 of Ministry of Agriculture of the People’s Republic of China. Beijing, China: Ministry of Agriculture of People’s Republic of China (2010).

Zhang, M., Song, G. W., Li, F. W., Li, C. C., Shen, P. Detection of genetically modified plants and derived products: Qualitative PCR method for herbicide-tolerant soybean MON89788 and its derivates. Bulletin No. 1485-6-2010 of Ministry of Agriculture of the People’s Republic of China. Beijing, China: Ministry of Agriculture of People’s Republic of China (2010).

Okuma, T. A. & Hellberg, R. S. Identification of meat species in pet foods using a real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay. Food Control 50, 9–17 (2015).

Chuah, L. et al. Mislabelling of beef and poultry products sold in Malaysia. Food Control 62, 157–164 (2016).

Owusu-Apenten, R. K. Food protein analysis: Quantitative effects of processing. New York: Marcel Dekker (2002).

Chen, X. Y., Wang, X. F., Zhou, Y., Miu, Q. M. & Xu, J. F. DNA Diagnostic Technology of the Deeply Processed Food from Genetic Modified Soybean. J Chinese Inst Food Sci Tech 4, 156–162 (2013).

Zhao, X. D., Li, X., Gao, S., Wang, Z. A. & Tao, F. F. Transgenic detection of several commercial soybean sauces. Food Sci Tech 5, 305–308 (2015).

Flores-Munguia, M. E., Bermudez-Almada, M. C. & Vazquez-Moreno, L. Detection of adulteration in processed traditional meat products. J Muscle Foods 11, 319–332 (2000).

Ma, Y. et al. Electrochemical determination of Melamine in milk powder based on silver nanoparticles/multi-walled carbon nanotubes/glassy carbon electrode. J Anal sci 4, 455–460 (2019).

Faraji, M. & Adeli, M. Sensitive determination of melamine in milk and powdered infant formula samples by high-performance liquid chromatography using dabsyl chloride derivatization followed by dispersive liquid–liquid microextraction. Food Chem 221, 139–146 (2017).

Vasimalai, N. & John Abraham, S. Picomolar melamine enhanced the fluorescence of gold nanoparticles: Spectrofluorimetric determination of melamine in milk and infant formulas using functionalized triazole capped gold nanoparticles. Biosens Bioelectron 42, 267–272 (2013).

Amaral, J. S., Santos, C. G., Melo, V. S., Oliveira, M. B. P. P. & Mafra, I. Authentication of a traditional game meat sausage (Alheira) by species-specific PCR assays to detect hare, rabbit, red deer, pork and cow meats. Food Res Int 60, 140–145 (2014).

Shears, P. Food fraud-a current issue but an old problem. Brit Food J 112, 198–213 (2010).

Singh, V. P. & Neelam, S. Meat species specifications to ensure the quality of meat: a review. Int J Meat Sci 1, 15–26 (2011).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Promotion of Innovation Ability Project of Sichuan Province Financial Budget, China [grant number 2016GXTZ-010] and the Outstanding Thesis Fund of Sichuan Academy of Agricultural Science, China [2017LWJJ-012 and 2018LWJJ-010]. We thank Lesley S Benyon, PhD, from Liwen Bianji, Edanz Group China (www.liwenbianji.cn/ac), for editing the English text of a draft of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Q.S. and Y.C. collected the sausage samples and conducted the experiments; L.Z. analysed the results; Q.S. and J.S. wrote the initial manuscript; H.O. revised part of the manuscript; J.S. supervised and revised the final manuscript. All the authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Song, Q., Chen, Y., Zhao, L. et al. Monitoring of sausage products sold in Sichuan Province, China: a first comprehensive report on meat species’ authenticity determination. Sci Rep 9, 19074 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-55612-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-55612-x

This article is cited by

-

PCR–RFLP and species-specific PCR efficiency for the identification of adulteries in meat and meat products

European Food Research and Technology (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.