Abstract

Mycobacterium tuberculosis infects over 10 million people annually and kills more people each year than any other human pathogen. The current tuberculosis (TB) vaccine is only partially effective in preventing infection, while current TB treatment is problematic in terms of length, complexity and patient compliance. There is an urgent need for new drugs to combat the burden of TB disease and the natural environment has re-emerged as a rich source of bioactive molecules for development of lead compounds. In this study, one species of marine sponge from the Tedania genus was found to yield samples with exceptionally potent activity against M. tuberculosis. Bioassay-guided fractionation identified bengamide B as the active component, which displayed activity in the nanomolar range against both drug-sensitive and drug-resistant M. tuberculosis. The active compound inhibited in vitro activity of M. tuberculosis MetAP1c protein, suggesting the potent inhibitory action may be due to interference with methionine aminopeptidase activity. Tedania-derived bengamide B was non-toxic against human cell lines, synergised with rifampicin for in vitro inhibition of bacterial growth and reduced intracellular replication of M. tuberculosis. Thus, bengamides isolated from Tedania sp. show significant potential as a new class of compounds for the treatment of drug-resistant M. tuberculosis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The M. tuberculosis bacillus is extremely hardy and intrinsically resistant to acid, alkali, lysozymes, osmotic lysis and antibiotic killing1,2,3. This high tolerance to stress is due to the impervious quality of the mycobacterial cell wall, which is hydrophobic and contains few porins, thus reducing rates of transport of hydrophilic molecules and antibiotics into the bacillus4,5. For these reasons, effective antibiotics for tuberculosis (TB) are difficult to develop. The current treatment for TB consists of combinations of rifampicin (RIF), isoniazid (INH), ethambutol (EMB) and pyrazinamide (PZA), taken from twice-weekly to daily, over a period of six to nine months6. The persistence of infection causes many issues with patient adherence to the regimen and poses a significant obstacle to successful treatment, particularly in areas where the infrastructure required to ensure reliable drug supply, correct prescription and dedicated patient follow-up may be lacking. Intermittent and incomplete treatment increases the risk of relapse and incidence of multiple (MDR-TB) and extensively drug-resistant TB (XDR-TB)7, so there is an urgent and pressing need to develop new drugs which can shorten and simplify TB treatment in order to combat the burgeoning MDR-TB pandemic.

Since the golden era of antibiotic discovery during the 1940s and 1950s, when more than 20 new classes of antibiotics entered clinical use, only two novel classes have been discovered8. Many current antibiotics are at their sixth or seventh generation of analogue development, and even these applications and approvals have declined steadily over time. One major factor behind the dearth of new antibiotics is the large but generally unsuccessful investment in genomic and target-based approaches by the pharmaceutical industry9. The failure of these approaches is likely due to difficulties in translating activity against a cell-free target to potency in more clinically relevant terms (such as the inhibition of whole cells), linked to adverse solubility or metabolic stability. Furthermore, the process of drug discovery and development is lengthy and expensive: it can take more than ten years and cost between US$800M and US$1Bn per drug10. The first-line treatment regimen for TB has not been updated to include new drugs for more than 50 years11.

Throughout history, the vast majority of antibiotics have been sourced from nature. The first antibiotic used in a clinical setting was pyocyanase, derived from Pseudomonas aeruginosa12. Due to the extraordinary diversity and hit rates found when screening natural products13, there is currently increasing interest in returning to natural sources for drug discovery14. The marine environment has come under scrutiny as a relatively untapped cornucopia of novel chemical scaffolds displaying potent bioactivity15. An estimated 25% of all Earth’s biodiversity lies in marine species16 and an estimated 3.7 × 1030 microorganisms live in the marine environment17. For example, marine actinomycetes are unique to the ocean environment and produce numerous chemical metabolites distinct from those of terrestrial species18. Invertebrate species such as sea sponges and tunicates are other sources of novel drugs, including the FDA-approved cancer drugs trabectedin19, cytarabine20 and eribulin21 and the antiviral vidarabine22. In the search for new TB drugs, the marine environment offers a promising avenue of inquiry. In this study, by mining marine samples we have identified bengamide B as a TB drug development lead, being highly potent, synergistic with existing TB drugs and capable of inhibiting growth of intracellular and drug-resistant M. tuberculosis.

Results

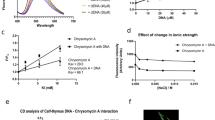

Identification of M. tuberculosis inhibitors by screening of marine samples

As a first step in the development of TB drug leads, marine samples with inhibitory activity against virulent M. tuberculosis H37Rv were identified. To determine this, 1434 diverse marine extracts23 were screened for their ability to inhibit M. tuberculosis growth in vitro. This identified 18 antimycobacterial hits, 11 of which derived from the Porifera phylum and five from the Chordata phylum (Table 1). MIC50 determination, defined as the concentration which resulted in 50% survival of bacteria in comparison to untreated controls, revealed that activity range was as low as 0.39 µg/mL (SN31863) and 1.56 µg/mL (SN31927). Samples were screened for toxicity against differentiated THP-1 macrophages by determining CC50 values (the concentration at which cellular viability was reduced by 50%) (Table 1). While some samples displayed general toxicity, with comparable MIC50 and CC50 values (e.g. SN3222), the two most effective antibacterial samples, SN31863 and SN31927, were non-toxic to THP-1 cells over a range of concentrations tested (Fig. 1A,B). As shown in Fig. 1C, extracts SN31863 and SN31927 were also non-cytotoxic against other cell lines tested, including hepatocyte cells (HepG2), epithelial lung cells (A549) and kidney cells (HEK293), suggesting that these compounds have some specificity for mycobacteria. The activity of SN31927 was similar to ethambutol (EMB) when testing in parallel with front-line TB drugs (Fig. 1D).

Screening of marine samples to identify potent, non-cytotoxic inhibitors of M. tuberculosis H37Rv. Lead samples SN31927 (A) and SN31863 (B) were incubated with M. tuberculosis H37Rv (OD600nm 0.001) or THP-1 cells (2 × 105 cells/well) and after a 5-day incubation resazurin (0.05%) was added and fluorescence measured. Graphs represent percentage viability of bacteria or cells compared with nontreated cells. The viability of HEK293, A549 and HepG2 cell lines was also assessed after incubation with 50 μg/ml crude extract and use of resazurin (0.05%) to calculate cellular viability (C). M. tuberculosis H37Rv was incubated with varying concentrations of SN31927 extract or two front-line TB, drugs, rifampicin (RIF) or isoniazid (INH), and bacterial viability determined after 5 days incubation (D). For all panels data show mean viability ± SEM of triplicate wells and is representative of two independent experiments.

Both SN31927 and SN31863 were derived from a Tedania sp. sea sponge collected from the East Diamond Islet of the Tregrosse Reefs, a Coral Sea reef off the coast of Queensland, Australia. Previously reported antibacterial activity of Tedania species has been associated with high concentrations of sequestered metals, particularly cadmium and zinc24. However, inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) revealed that insignificant amounts of cadmium (40 ppm) or zinc (0.037 ppm) were present in SN31863, the crude sponge extract, compared to values of 2000–15,000 ppm cadmium and 5000–5100 ppm zinc reported by Capon et al.24. This suggests that the antimycobacterial activity exhibited by samples SN31927 and SN31863 is due to a bioactive compound produced by the organism, and not general metal toxicity.

Purification of lead samples and characterisation of active fractions

High performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) of SN31863 yielded 12 fractions, F1 to F12 (Fig. 2A), nine of which were antimycobacterial and non-cytotoxic (Table 2). F2 did not inhibit M. tuberculosis H37Rv, while insufficient material was recovered from F7 and F9 for detailed bioassay analysis. MIC50 determination identified F10, F11 and F12 as the most potent, with F11 and F12 both active down to the low nanogram range (0.078 µg/ml) (Table 2). Encouragingly, all 3 samples displayed no toxicity for the four mammalian cell lines tested (Table 2). To further characterise these 3 fractions, their intracellular antimycobacterial activity was assessed using M. tuberculosis H37Rv-infected THP-1 macrophages. All 3 samples significantly inhibited intracellular bacterial growth in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2B). Testing F10, F11 and F12 against clinical isolates of drug-resistant M. tuberculosis showed that all 3 maintain their potent activity against INH-resistant and RIF/INH-resistant M. tuberculosis (Table 3). These findings indicate that the mechanism of action of the Tedania-derived compound(s) is likely different to those of existing TB drugs, and as such, these fractions are promising drug leads.

Purification and evaluation of potent, non-cytotoxic inhibitors of M. tuberculosis H37Rv. (A) Semi-preparative HPLC was carried out on a reversed-phase column (Waters X-bridge C18, 250 mm × 4.6 mm, 5 µm), gradient elution of 0 to 100% acetonitrile–H2O, flow rate 1 mL/min over 80 minutes, monitored at 215 nm, with automated fraction collection to yield 12 fractions in the region of interest. (B) Intracellular activity assays were conducted by infecting 2 × 105 THP-1 cells/well with 106 M. tuberculosis H37Rv for four hours before treatment with F10, F11 or F12 for seven days, lysis of cells and plating for CFU quantifications. Samples were tested in triplicate in two independent experiments. The significance of differences between the untreated groups and other groups were analysed by ANOVA with Tukey’s Multiple Comparisons test **p < 0.01, ****p < 0.0001.

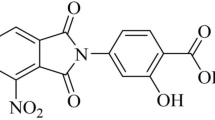

Structure elucidation and identification of bioactive molecules

Structure elucidation efforts focused on F12, the most cleanly eluted fraction. Analysis by HRMS-ESI indicated a molecular formula of C32H58N2NaO8 [M + Na]+ (0.1 ppm) from the adduct ion, and five DBRE were calculated from this formula (Fig. S1). F12 was then characterised by NMR (Figs S2 and S3). 13C NMR was used to identify the four multiple bonds (Table S1) as an ester (δ 172.65), two amides (δ 172.31, 170.33) and an (E)-CHCH = CHCH array (δ 138.56, 128.04). The presence of a single ring was deduced to be the fifth DBRE apparent in the molecular formula. Additional functional groups included three CH(OH) groups (δ 73.22, 72.94, 71.18), a CH(O-CH3) group (δ 81.95, 57.77), a CH flanked by a carbonyl group and an amide NH (δ 51.16, 172.31), a second amide NH connected to a CH3 (δ 52.7, 36.11), two CH2 groups (δ 138.56, 128.04) and an aliphatic linear chain attached to a carbonyl (δ 172.65, 31.74, 29.49–28.82, 22.75, 14.38). The COSY spectrum contained correlations for C-1 (δ 0.94(7), d) coupled to C-2 (δ 2.15, qqd), which was in turn coupled to C-3 (δ 5.59, ddd), C-4 (δ 5.37, ddd) and C-5 (δ 3.97, dd) (Fig. 3A). The COSY spectrum also revealed the connectivities shown for C-1/C-15 to C-8, C-10 to C-13 and C-18 to C-30 (Fig. 3A). The COSY correlation between C-8 and the methoxy protons revealed the location of the O-CH3, and assignment of C-8 adjacent to a carbonyl group was based on both COSY data and HMBC. Other key HMBC correlations included connections between C-9 to H-7 and H-10, C-16 to H10 and N-CH3, and C-17 to H-18 (Fig. S4).

Preliminary analysis of these data and comparison with literature indicated close similarity with the previously reported bengamide class of sponge-derived natural products (Fig. 3B). The mass data were in agreement with those in the literature for the known marine heterocycle, bengamide B25. Subsequent consideration of the NMR data confirmed this, through diagnostic peaks at δ 5.78, 5.44, 4.60 and 4.21, each of which corresponds to regions of the amide core structure (Fig. 3A). The position and multiplicity of key signals in the 1H NMR spectrum of F12 (500 MHz, CDCl3) closely matched previously reported data, confirming F12 as bengamide B (Fig. 3B and Table S2).

Inhibitory activity of bengamide B

Bengamide B from various species inhibits activity of methionine aminopeptidase (MetAP), an enzyme that removes the N-terminal methionine from nascent proteins26,27,28. To confirm this activity in Tedania-derived bengamide B, MetAP inhibition against purified enzymes from M. tuberculosis, E. faecalis and H. sapiens was assessed. Tedania-derived bengamide B was a highly potent MetAP inhibitor across the 3 different enzymes tested, MtMetAP1c, EfMetAP1b and HsMetAP1b (72.84%, 83.33% and 84.72% inhibition respectively). Interestingly, bengamide B showed strong inhibition of EfMetAP1b, but this was not reflected in the results of bacterial inhibition screening, where bengamide B was not able to inhibit E. faecalis growth in vitro (data not shown). Similarly, although bengamide B was shown to inhibit HsMetAP1b, it was not cytotoxic against any tested human cell line in vitro (Table 2).

Combination therapy against TB using bengamide B

Multidrug combinations are required to treat TB, and novel drug leads must be able to work in synergy with existing front-line TB drugs. To investigate potential synergistic effects between bengamide B and existing TB drugs, suboptimal concentrations of rifampicin (RIF) (1 nM) were incubated with M. tuberculosis H37Rv in combination with bengamide B at a range of concentrations (0.03 μM, 0.11 μM, 0.33 μM, 1 μM). The results were analysed using the Chou-Talalay combination index (CI) equation29 and revealed strong synergy between bengamide B and rifampicin (CI = 0.1–0.3) (Fig. 4A). Furthermore, combining bengamide B and rifampicin allows for a dose reduction index (DRI) from 8-fold to over 200-fold for rifampicin and 3-fold to over 14-fold for bengamide B over a range of concentration combinations (Fig. 4B).

Evaluation of bengamide B and rifampicin synergy. Serial three-fold dilutions of bengamide B (starting conc. 1 μM) were tested in combination with 1 nM rifampicin over four days before the addition of 0.05% w/v/ resazurin overnight. (A) Chou-Talalay plot showing CI against Fa. (B) Chou-Martin plot showing log(DRI) against Fa.

Discussion

Despite the heavy burden of TB disease and growing rates of drug resistance worldwide, efforts to develop new drugs for treatment have met with limited success. The two most recently approved drugs for TB are bedaquiline, discovered through investigation and optimisation of the diarylquinolone compound family30 and licensed for use by the FDA in 201231, and delamanid, licensed in 201432. Since then, the treatments which have progressed furthest through clinical trials are simply combinations of existing drugs33. Further work is urgently needed to bring novel and overlooked molecular scaffolds through development and into the TB drug pipeline. This study aimed to mine the marine biosphere in the search for potential TB drug leads using whole-cell screening techniques. The results reiterate that marine organisms are rich and underutilised sources of bioactive molecules. The most active antimycobacterial compounds identified in this study derived from sea sponges and sea squirts of the Porifera and Chordata phyla. As sessile filter feeders, these organisms rely heavily on secondary metabolites to gain competitive advantage in the struggle for space and resources in their benthic habitats34. Nine samples among the 18 antimycobacterial hits were broadly cytotoxic, and likely contain highly potent biological deterrents specifically produced by the organism, like other well-known examples such as cone shell poison, tetrodotoxin from puffer fish and stonefish neurotoxin35,36. Toxicity is the predominant cause of failure in marine natural product drug screening, with the cost of attrition increasing as samples progress through preclinical testing37. Consequently, any hits which resulted in cytotoxicity against any of the tested human cell lines were discounted from further investigation.

Tedania sea sponges are known to cause blistering and peeling upon contact with bare skin38 and are therefore recognised as producers of potent bioactive molecules. T. ignis is the Tedania species that has been best documented in drug discovery studies, giving rise to several novel indoles39, an atisanediol40, a δ-lactam41, diketopiperazines39, the tedanolide family of potent antitumour macrolides42, and the tedanols, a group of anti-inflammatory diterpenes43. T. anhelans has given rise to some interesting pyrazole acids44, and T. digitis has been documented as the source of tedaniaxanthin45. All of these novel molecules and scaffolds isolated from Tedania spp. are larger (50–600 g/mol) aromatic compounds with some level of cytotoxicity. To date, the only antimycobacterial agents isolated from Tedania sponges were derived from a symbiotic strain of Penicillium chrysogenum with broad-spectrum inhibitory activity against S. aureus, P. aeruginosa, M. tuberculosis H37Ra, M. avium, M. smegmatis, M. fortuitum, M. vaccae, Aeromonas hydrophila, and Vibrio cholerae46. Purification of the active Tedania sp. sponge extract in the current study resulted in 11 active antimycobacterial fractions, one of which was resolved through mass spectrometry and NMR analysis as bengamide B. The other fractions either resulted in too little dry weight of material, or were not sufficiently pure for structure elucidation.

The bengamides are a series of small molecules consisting of a core amide ring, a polyketide chain and an alkyl ester. Originally discovered as antiparasitic compounds in a study of Indo-Pacific sponge extracts, bengamides A and B were first isolated from Jaspis cf. coriacea sponges in 198625. Since then, the bengamide class of molecules has been found to have nanomolar antitumour activity47 due to the inhibition of methionine aminopeptidase (MetAP) type 1 and type 228, arresting cell growth at phases G1 and G2/M48. Bengamides have also been found to inhibit the NF-κB pathway, acting as potent anti-inflammatory compounds49. However the best-characterised bengamide, bengamide B, has gained most recognition as an antitumour agent. When used to treat MDA-MB435 human breast cancer xenografts on athymic rats in vivo, bengamide B significantly inhibits growth of MDA-MB435 human breast cancer xenografts49 and analogues of treatment have progressed to clinical trials for treatment of refractory solid phase tumours50. Interestingly, despite the levels of tumour cell line inhibition reported for bengamide B in the literature, the bengamide B natural product isolated in the current study did not display any notable cytotoxicity against THP-1 derived macrophages, HepG2, HEK293 or A549 cells (Fig. 1). Further cytotoxicity studies, both in vitro and in vivo, are required to probe the effects of bengamide B in mammalian and human systems in order to inform the TB drug lead development process. One previous study has attempted to develop TB drug leads by synthesising bengamide derivatives to bind to the four different metalloforms of MtMetAP1a and MtMetAP1c (Co, Mn, Ni, Fe)27. The two best-performing derivatives were potent MetAP inhibitors but resulted in modest MIC values of 122 and 53.9 µM respectively against mycobacteria, in contrast to the nM activity observed for Tedania-dervied bengamide B (Table 2).

It has been well established that potent target inhibition does not necessarily translate to activity in clinically relevant terms, and target-based approaches to drug design have in fact been blamed for high rates of attrition and low productivity in pharmaceutical research51. We observed that while bengamide B is strongly inhibitory against MtMetAP1c, EfMetAP1b and HsMetAP1b, it is not able to inhibit the growth of E. faecalis, or THP-1 derived macrophages, HepG2, HEK293 or A549 cells (Table 2). MetAPs are essential enzymes responsible for the cotranslational removal of N-terminal methionine from newly synthesised proteins, triggering localisation, activation or degradation52. Found across both prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells, MetAPs have been investigated as attractive anticancer, anti-parasitic, and anti-atherosclerotic drug targets over the years53. Bengamides are known to inhibit both MetAP1 and MetAP2 in humans, and it has been postulated that this non-selective activity is responsible for clinical cytoxicity as a result of global N-terminal methionine processing inhibition26.

There are no records in the literature to date of evolved resistance against bengamide B, even though the inhibitory properties of bengamide B have been explored in Streptococcus pyrogenes, Nippostrongylus braziliensis and various human cell lines25. However, one genetically engineered mechanism of resistance to MetAP inhibition in M. tuberculosis has been reported. The overexpression of either MtMetAP1a or MtMetAP1c in knock-in strains of M. tuberculosis confers resistance to the MetAP inhibitor 2,3-dichloro-1,4-naphthoquinone54. This reinforces the hypothesis that MetAPs are essential, non-redundant enzymes, though other effects have been reported from MetAP inhibition. For example, the MetAP inhibitors ovalicin and fumagillin are able to inhibit angiogenesis55,56. As M. tuberculosis is notorious for upregulating host angiogenesis to facilitate bacterial spread from the site of infection57, targeting MetAPs is an attractive treatment strategy. No TB drug in current use is known to target MtMetAPs and it is likely that drug-resistant strains have not been selected for resistance to MetAP inhibitors. This has been confirmed experimentally in this study by the demonstrated ability of bengamide B to strongly inhibit multidrug resistant M. tuberculosis strains. The results of the microdilution drug combination assay indicate that bengamide B is able to work in synergy with rifampicin to inhibit the growth of M. tuberculosis H37Rv (Fig. 4), suggesting bengamide B is a promising candidate to investigate as a means of improving current suboptimal treatment of drug-resistant and drug-susceptible TB.

In conclusion, this study has identified a Tedania sp. sea sponge as a source of potent, non-cytotoxic antimycobacterial extracts with activity against clinical strains of MDR-TB. With the critical shortage of novel scaffolds in the TB drug pipeline, all avenues must be explored in the search for new drug leads. This study has reiterated the wealth of bioactive molecules which can be sourced from the marine environment, both from sea sponges and their associated microflora. Future directions include the purification of additional bioactive compounds from the identified Tedania extract for characterisation and further testing.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial strains, media and culture conditions

M. tuberculosis H37Rv (ATCC27294) was used for this study, along with the clinical M. tuberculosis 3410 (INH-resistant), 1863 (RIF/INH-resistant) and 2441 (RIF/INH/EMB-resistant) isolates. Middlebrook 7H9 media supplemented with albumin-dextrose-catalase (ADC; 10% v/v), glycerol (0.2% v/v) and Tween-80 (0.05% v/v) was used to grow cultures which were incubated at 37 °C in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator.

Cell lines, media and culture conditions

THP-1 (ATCC TIB-202), HepG2 (ATCC HB-8065), HEK293 (ATCC CRL-1573) and A549 (ATCC CCL-185) cells were used in this study. Frozen cell stocks were taken from liquid nitrogen, thawed and grown in cell culture flasks containing 25 mL RPMI for THP-1 cells, or DMEM for HepG2, HEK293 and A549 cells. All cell media was supplemented with 10% v/v foetal calf serum, 100 U/mL penicillin and 0.1% w/v streptomycin. The flasks were incubated in a 5% CO2 incubator at 37 °C until they reached ~80% confluency, at which point the cells were trypsinised if required and counted before resuspension at required cell concentrations.

Marine samples

Test samples consisted of 239 crude extracts obtained from marine organisms provided by the Australian Institute of Marine Science (AIMS). Crude extracts were sequentially fractionated in methanol by AIMS using a pre-equilibrated solid phase extraction Phenomenex Strata C18-E cartridge (55 μm, 70 Å, 500 mg/6 mL) to generate 1434 samples. All samples were supplied in 100% DMSO solution at 5 mg/mL and stored at -80 °C. The marine sponge Tedania sp. was collected from the East Diamond Islet of the Tregrosse Reefs off the coast of Queensland, Australia. The sponge was deep-frozen immediately after collection and freeze-dried before extraction with methanol. This crude extract was then stored at −80 °C.

Screening for mycobacterial inhibition

The resazurin reduction assay is a quantitative, colorimetric means of determining cell viability and was employed throughout this study to determine growth inhibition58. Bacterial strains were grown to log phase and diluted to a stock concentration of OD600 = 0.001. Test samples (0.5 mg/mL) or positive controls (5 μM rifampicin) were diluted in dH2O in 96 well plates and 10 μL of each sample dispensed into separate wells. Ninety μL of bacterial suspension was added to each well and incubated at 37 °C for 4 days, after which 10 μL of 0.05% resazurin was added to each well. After overnight incubation, fluorescence readings were taken at 590 nm after excitation at 544 nm using the FLUOstar Omega Microplate Reader (BMG Labtech, Ortenburg/Germany). Percentage viability was calculated in comparison to the average of untreated control wells after normalising for background readings. Z’-factors were greater than 0.5 for all assays59. For the clinical isolates of drug-resistant M. tuberculosis, plates were incubated for 7 days before the addition of resazurin for 24 h and results of the resazurin reduction assay were read by eye. To determine MIC50 values, serial two-fold dilutions of test samples were made using dH2O to give final sample concentrations of 500 µg/mL to 0.01 µg/mL, which were tested as described above, and MIC50 was determined according to percentage survival in comparison to untreated controls. To assess drug synergy, M. tuberculosis H37Rv (OD600 = 0.001) was added to wells containing suboptimal concentrations of rifampicin (1 nM) or isoniazid (0.25 µM) together with with 1:3 serial dilutions of bengamide B starting at MIC = 1 μM. The plates were incubated and treated with resazurin before fluorescence readings, as described above.

Screening for cytotoxicity

Cells were seeded into 96-well plates at THP-1 cells (2 × 105 cells/well) were treated with 100 ng/mL phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) before seeding in order to stimulate differentiation into macrophages-like cells. All cells were left to adhere in a 5% CO2 incubator at 37 °C for 48 h before test samples were added to a final concentration of 50 µg/mL. Plates were incubated for 4 days, then treated with resazurin for 16 h and read for fluorescence as per the previous section. To determine CC50 values, serial two-fold dilutions of test samples were made using dH2O to give final sample concentrations of 500 µg/mL to 3.9 µg/mL, which were tested as described above.

Heavy metal content analysis

Prior to analysis, solid sponge sample was dissolved in concentrated nitric acid, then adjusted to 14% v/v concentration of nitric acid using Milli-Q H2O before undergoing microwave digestion and passing through a 0.4 µm syringe filter. Cadmium and zinc standards were prepared by diluting stock standard solutions to levels in the linear range for the instrument using the same acidified Milli-Q water used in the preparation of the sponge digestate. Inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES) analyses were performed on the Perkin-Elmer OPTIMA 7000 DV Inductively Coupled Plasma-Optical Emission Spectrometer equipped with an axial torch, cyclonic spray chamber, and Meinhard® Type C concentric nebuliser. The operating conditions were RF Power 1300 W, plasma flow 15 L/min, auxiliary flow 0.2 L/min, nebuliser flow 0.8 L/min and a viewing distance of 15.0 mm. Each element was initially analysed by three spectral lines and then a single spectral line that exhibited low interference and high analytical signal and background ratios were selected for each element. These spectral lines were 228.804 nm (Cd) and 213.860 (Zn). Each element was quantified by the average of two readings.

Purification and identification of inhibitory compounds

Semi-preparative HPLC of Tedania sp. sample was carried out on a reversed-phase column (Waters X-bridge C18, 250 mm × 4.6 mm, 5 µm), 100 µL sample injection and a gradient elution with 0 to 100% acetonitrile–H2O at 1 mL/min over 80 minutes, monitored at 215 nm. Fractions were collected, freeze dried and dissolved in DMSO at 5 mg/mL for testing against M. tuberculosis H37Rv and THP-1 derived macrophages. Electrospray Ionisation (ESI) High Resolution Mass Spectrometry (HRMS) was recorded in a positive ion mode on a Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometer (Apex Qe 7T, Bruker Daltonics, Bremen, Germany) with an Apollo II electrospray ionisation (ESI) ion source. The solvent for HRMS was CH3CN. NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker AVANCE III 500 (1H at 500.13 MHz and 13C at 125.21 MHz). Spectra were referenced to residual solvent resonances (CHCl3 δ 7.26 (1H) and δ 77.16 (13C); DMSO δ 2.50 (1H) and δ 39.52 (13C)). All samples were dissolved in approximately 45 μL of DMSO-d6 or CDCl3 and transferred to 1.7 mm NMR tubes. All data were collected and processed using Bruker Topspin 3.5 software. Chemical shifts (δ) are reported in ppm, coupling constants in Hz, and for signal multiplicities: s = singlet, d = doublet, dd = doublet of doublet, ddd = doublet of doublet of doublet, dddd = doublet of doublet of doublet of doublet, qqd = quartet of quartet of doublet, t = triplet, m = multiplet.

Intracellular antimycobacterial activity assay

THP-1 cells were grown to ~80% confluency in cell culture flasks and then counted, dispensed into 96-well flat-bottomed wells at 2 × 105 cells/well and left to differentiate as described above. Cells were then infected with 106 M. tuberculosis H37Rv in complete RPMI for four hours. The media was removed and the cells gently washed 3 times with 2% FBS in PBS. One hundred μL complete RPMI was then added to each well along with test samples at a final concentration of 50 µg/mL. Rifampicin at 5 µM was used as a positive control for intracellular inhibition. The plates were incubated at 37 °C in 5% CO2 for 7 days, following which cells were lysed with cold dH2O and bacteria enumerated by plating on Middlebrook 7H11 agar supplemented with oleic-acid-albumin-dextrose catalase (OADC; 10% v/v) and glycerol (0.5% v/v) for 3 weeks at 37 °C.

Combination analysis

Synergism between bengamide B and rifampicin was determined by calculating the CI (CI = D1/Dx1 + D2/Dx2, where Dx1 and Dx2 indicate the individual dose of bengamide B and rifampicin required to inhibit a given level of viability index, and D1and D2 are the doses of bengamide B and rifampicin necessary to produce the same effect in combination, respectively). CI values of <1, =1, and >1 indicate synergism, additive effect, and antagonism of drugs, respectively. The DRI for both bengamide B and rifampicin were calculated using the multiple drug effect equation (DRI = Dx1/D1), where DRI values quantify how many folds of dose reduction result from drug combination in comparison to single drug treatment. Both CI and DRI were plotted against fraction affected (FA) to generate a Chou-Talalay and Chou-Martin plot providing visual illustration of synergism and dose-reduction.

MetAP inhibition

MtMetAP1c, EfMetAP1b and HSMetAP1b enzymes were expressed in E. coli and purified60,61,62. Samples were tested at a single concentration of 50 µM and enzymatic activity was monitored by fluorescence readings following hydrolysis of the fluorogenic substrate, methionyl aminomethylcoumarin, at room temperature. Percentage inhibition was calculated in comparison to negative controls.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 6 or 7 software (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA). Differences between two groups were analysed by Student’s t-test, or between multiple groups by ANOVA with Tukey’s Multiple Comparisons test and were considered significant when the P values were ≤0.05.

Data Availability

Data from this study will be made fully available and without restriction upon request.

References

Jackett, P. S., Aber, V. R. & Lowrie, D. B. Virulence and resistance to superoxide, low pH and hydrogen peroxide among strains of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Gen Microbiol 104, 37–45 (1978).

Vandal, O. H., Nathan, C. F. & Ehrt, S. Acid resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Bacteriol 191, 4714–4721 (2009).

Gerston, K. F., Blumberg, L., Tshabalala, V. A. & Murray, J. Viability of mycobacteria in formalin-fixed lungs. Hum Pathol 35, 571–575 (2004).

Brennan, P. J. & Nikaido, H. The envelope of mycobacteria. Annu Rev Biochem 64, 29–63 (1995).

Trias, J., Jarlier, V. & Benz, R. Porins in the cell wall of mycobacteria. Science 258, 1479–1481 (1992).

Schaberg, T. Treatment of tuberculosis. Current standards. Internist (Berl) 56, 1379–1388 (2015).

Mahmoudi, A. & Iseman, M. D. Pitfalls in the care of patients with tuberculosis. Common errors and their association with the acquisition of drug resistance. JAMA 270, 65–68 (1993).

Ventola, C. L. The antibiotic resistance crisis: part 1: causes and threats. P T 40, 277–283 (2015).

Brotz-Oesterhelt, H. & Sass, P. Postgenomic strategies in antibacterial drug discovery. Future Microbiol 5, 1553–1579 (2010).

DiMasi, J. A., Hansen, R. W. & Grabowski, H. G. The price of innovation: new estimates of drug development costs. J Health Econ 22, 151–185, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0167-6296(02)00126-1 (2003).

WHO. Global Tuberculosis Report 2017 (2017).

Emmerich, R. & Low, O. Bakteriolytische Enzyme als Ursache der erworbenen Immunität und die Heilung von Infectionskrankheiten durch dieselben. Z Hyg Infektionskr 31, 1–65 (1899).

Sukuru, S. C. et al. Plate-based diversity selection based on empirical HTS data to enhance the number of hits and their chemical diversity. J Biomol Screen 14, 690–699 (2009).

Rutledge, P. J. & Challis, G. L. Discovery of microbial natural products by activation of silent biosynthetic gene clusters. Nat Rev Microbiol 13, 509–523 (2015).

Mehbub, M. F., Perkins, M. V., Zhang, W. & Franco, C. M. M. New marine natural products from sponges (Porifera) of the order Dictyoceratida (2001 to 2012); a promising source for drug discovery, exploration and future prospects. Biotechnol Adv 34, 473–491 (2016).

Mora, C., Tittensor, D. P., Adl, S., Simpson, A. G. B. & Worm, B. How Many Species Are There on Earth and in the Ocean? PLOS Biology 9, e1001127 (2011).

Kennedy, J. et al. Marine metagenomics: new tools for the study and exploitation of marine microbial metabolism. Mar Drugs 8, 608–628 (2010).

Subramani, R. & Aalbersberg, W. Marine actinomycetes: an ongoing source of novel bioactive metabolites. Microbiol Res 167, 571–580 (2012).

Le Cesne, A. & Reichardt, P. Optimizing the use of trabectedin for advanced soft tissue sarcoma in daily clinical practice. Future Oncol 11, 3–14 (2015).

Chhikara, B. S. & Parang, K. Development of cytarabine prodrugs and delivery systems for leukemia treatment. Expert Opin Drug Deliv 7, 1399–1414 (2010).

Garrone, O. et al. Eribulin in advanced breast cancer: safety, efficacy and new perspectives. Future Oncol 13, 2759–2769 (2017).

Whitley, R. et al. A controlled trial comparing vidarabine with acyclovir in neonatal herpes simplex virus infection. Infectious Diseases Collaborative Antiviral Study Group. N Engl J Med 324, 444–449 (1991).

Evans-Illidge, E. A. et al. Phylogeny drives large scale patterns in Australian marine bioactivity and provides a new chemical ecology rationale for future biodiscovery. PLoS One 8, e73800 (2013).

Capon, R. J. et al. Extraordinary Levels of Cadmium and Zinc in a Marine Sponge, Tedania-Charcoti Topsent - Inorganic Chemical Defense Agents. Experientia 49, 263–264 (1993).

Quinoa, E., Adamczeski, M., Crews, P. & Bakus, G. J. Bengamides, Heterocyclic Anthelmintics from a Jaspidae Marine Sponge. Journal of Organic Chemistry 51, 4494–4497 (1986).

Hu, X. et al. Regulation of c-Src nonreceptor tyrosine kinase activity by bengamide A through inhibition of methionine aminopeptidases. Chem Biol 14, 764–774 (2007).

Lu, J. P. et al. Inhibition of Mycobacterium tuberculosis methionine aminopeptidases by bengamide derivatives. ChemMedChem 6, 1041–1048 (2011).

Towbin, H. et al. Proteomics-based target identification: bengamides as a new class of methionine aminopeptidase inhibitors. J Biol Chem 278, 52964–52971 (2003).

Chou, T. C. & Talalay, P. Quantitative analysis of dose-effect relationships: the combined effects of multiple drugs or enzyme inhibitors. Adv Enzyme Regul 22, 27–55 (1984).

Diacon, A. H. et al. The diarylquinoline TMC207 for multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. N Engl J Med 360, 2397–2405 (2009).

Conradie, F. et al. Clinical access to Bedaquiline Programme for the treatment of drug-resistant tuberculosis. S Afr Med J 104, 164–166 (2014).

Ryan, N. J. & Lo, J. H. Delamanid: first global approval. Drugs 74, 1041–1045 (2014).

Palomino, J. C. & Martin, A. Tuberculosis clinical trial update and the current anti-tuberculosis drug portfolio. Curr Med Chem 20, 3785–3796 (2013).

Thakur, A. N. et al. Antiangiogenic, antimicrobial, and cytotoxic potential of sponge-associated bacteria. Mar Biotechnol (NY) 7, 245–252 (2005).

Wilson, D. M., Puyana, M., Fenical, W. & Pawlik, J. R. Chemical defense of the Caribbean reef sponge Axinella corrugata against predatory fishes. J Chem Ecol 25, 2811–2823 (1999).

Wu, Z. Y., Li, Y. T. & Xu, D. J. Diaqua(2,2′-diamino-4,4′-bi-1,3-thiazole)oxosulfatovanadium(IV) tetrahydrate. Acta Crystallogr C 61, m463–465 (2005).

Kola, I. & Landis, J. Can the pharmaceutical industry reduce attrition rates? Nat Rev Drug Discov 3, 711–715 (2004).

Isbister, G. K. & Hooper, J. N. Clinical effects of stings by sponges of the genus Tedania and a review of sponge stings worldwide. Toxicon 46, 782–785 (2005).

Dillman, R. L. & Cardellina, J. H. Aromatic Secondary Metabolites from the Sponge Tedania-Ignis. Journal of Natural Products 54, 1056–1061 (1991).

Schmitz, F. J. et al. Metabolites from the Marine Sponge Tedania-Ignis - a New Atisanediol and Several Known Diketopiperazines. Journal of Organic Chemistry 48, 3941–3945 (1983).

Cronan, J. M. Jr. & Cardellina, J. H. II A Novel δ-Lactam from the Sponge Tedania ignis. Natural Product Letters 5, 85–88 (1994).

Chevallier, C. et al. Tedanolide C: A potent new 18-membered-ring cytotoxic macrolide isolated from the Papua New Guinea marine sponge Ircinia sp. Journal of Organic Chemistry 71, 2510–2513 (2006).

Costantino, V. et al. Tedanol: A potent anti-inflammatory ent-pimarane diterpene from the Caribbean Sponge Tedania ignis. Bioorgan Med Chem 17, 7542–7547 (2009).

Parameswaran, P. S., Naik, C. G. & Hegde, V. R. Secondary metabolites from the sponge Tedania anhelans: Isolation and characterization of two novel pyrazole acids and other metabolites. Journal of Natural Products 60, 802–803 (1997).

Tanaka, Y. & Katayama, T. Biochemical Studies on the Carotenoids in Porifera: The Structure of Tedaniaxanthin. Nippon Suisan Gakkaishi 45, 633–634 (1979).

Visamsetti, A., Ramachandran, S. S. & Kandasamy, D. Penicillium chrysogenum DSOA associated with marine sponge (Tedania anhelans) exhibit antimycobacterial activity. Microbiol Res 185, 55–60 (2016).

Kinder, F. R. Jr. et al. Total syntheses of bengamides B and E. J Org Chem 66, 2118–2122 (2001).

Phillips, P. E. et al. Bengamide E arrests cells at the G1/S restriction point and within the G2/M phase of the cell cycle. Proc Annu Meet Am Assoc Cancer Res 41, 59 (2000).

Johnson, T. A. et al. Myxobacteria versus sponge-derived alkaloids: the bengamide family identified as potent immune modulating agents by scrutiny of LC-MS/ELSD libraries. Bioorg Med Chem 20, 4348–4355 (2012).

Dumez, H. et al. A phase I and pharmacokinetic study of LAF389 administered to patients with advanced cancer. Anticancer Drugs 18, 219–225 (2007).

Swinney, D. C. & Anthony, J. How were new medicines discovered? Nat Rev Drug Discov 10, 507–519 (2011).

Bradshaw, R. A., Brickey, W. W. & Walker, K. W. N-terminal processing: the methionine aminopeptidase and N alpha-acetyl transferase families. Trends Biochem Sci 23, 263–267 (1998).

Vaughan, M. D., Sampson, P. B. & Honek, J. F. Methionine in and out of proteins: targets for drug design. Curr Med Chem 9, 385–409 (2002).

Olaleye, O. et al. Methionine Aminopeptidases from Mycobacterium tuberculosis as Novel Antimycobacterial Targets. Chemistry & Biology 17, 86–97 (2010).

Griffith, E. C. et al. Methionine aminopeptidase (type 2) is the common target for angiogenesis inhibitors AGM-1470 and ovalicin. Chemistry & Biology 4, 461–471 (1997).

Sin, N. et al. The anti-angiogenic agent fumagillin covalently binds and inhibits the methionine aminopeptidase, MetAP-2. P Natl Acad Sci USA 94, 6099–6103 (1997).

Polena, H. et al. Mycobacterium tuberculosis exploits the formation of new blood vessels for its dissemination. Sci Rep 6, 33162 (2016).

Yu, M. et al. Nontoxic Metal-Cyclam Complexes, a New Class of Compounds with Potency against Drug-Resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Med Chem 59, 5917–5921 (2016).

Zhang, J. H., Chung, T. D. Y. & Oldenburg, K. R. A simple statistical parameter for use in evaluation and validation of high throughput screening assays. Journal of Biomolecular Screening 4, 67–73 (1999).

Hu, X. Y., Addlagatta, A., Matthews, B. W. & Liu, J. O. Identification of pyridinylpyrimidines as inhibitors of human methionine aminopeptidases. Angew Chem Int Edit 45, 3772–3775 (2006).

Kishor, C., Gumpena, R., Reddi, R. & Addlagatta, A. Structural studies of Enterococcus faecalis methionine aminopeptidase and design of microbe specific2,2′-bipyridine based inhibitors. Medchemcomm 3, 1406–1412, https://doi.org/10.1039/c2md20096a (2012).

Reddi, R. et al. Selective targeting of the conserved active site cysteine of Mycobacterium tuberculosis methionine aminopeptidase with electrophilic reagents. Febs J 281, 4240–4248 (2014).

Acknowledgements

We thank the Australian Institute of Marine Science for provision of marine samples. This work was supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Project APP1084266 and the NHMRC Centre of Research Excellence in Tuberculosis Control (APP1043225). The NSW Government provided support through its infrastructure grant to the Centenary Institute. DQ was a recipient of scholarship funding from the NHMRC Centre of Research Excellence in Tuberculosis Control and an Australian Postgraduate Award. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and interpretation, or the decision to submit the work for publication. There are no conflicts of interest to declare.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.Q., P.R. and J.T. conceived and designed the study. D.Q., G.N., E.M., V.S., I.L., N.L., V.P. and A.A. performed the experiments. All authors analysed and interpreted the data. D.Q. and J.T. wrote the first draft of the manuscript, all authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Quan, D.H., Nagalingam, G., Luck, I. et al. Bengamides display potent activity against drug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Sci Rep 9, 14396 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-50748-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-50748-2

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.