Abstract

The cannabinoid alkyl side-chain represents an important pharmacophore, where genetic targeting of alkyl homologs has the potential to provide enhanced forms of Cannabis for biopharmaceutical manufacture. Delta(9)-tetrahydrocannabinolic acid (THCA) and cannabidiolic acid (CBDA) synthase genes govern dicyclic (CBDA) and tricyclic (THCA) cannabinoid composition. However, the inheritance of alkyl side-chain length has not been resolved, and few studies have investigated the contributions and interactions between cannabinoid synthesis pathway loci. To examine the inheritance of chemical phenotype (chemotype), THCAS and CBDAS genotypes were scored and alkyl cannabinoid segregation analysed in 210 F2 progeny derived from a cross between two Cannabis chemotypes divergent for alkyl and cyclic cannabinoids. Inheritance patterns of F2 progeny were non-Gaussian and deviated from Mendelian expectations. However, discrete alkyl cannabinoid segregation patterns consistent with digenic as well as epistatic modes of inheritance were observed among F2 THCAS and CBDAS genotypes. These results suggest linkage between cannabinoid pathway loci and highlight the need for further detailed characterisation of cannabinoid inheritance to facilitate metabolic engineering of chemically elite germplasm.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cannabis is a phylogeographically divergent1 notably heterozygote2 anemophilous (wind pollinated) angiosperm genus3, which has undergone sub-selection for fibre, seed4, recreational drug, and medical end-uses5,6. Despite a long history of domestication dating back several thousand years7, exploitation of Cannabis ex situ genetic resources using modern improvement strategies has been hampered due to legal constraints relating to the plant’s status as a narcotic8.

Cannabis plants produce a class of therapeutically important isoprenylated resorcinyl polyketides9, more commonly identified as (phyto)cannabinoids10. These accumulate predominantly within capitate stalked trichromes on floral tissues11. Cannabinoids are synthesised with a carboxylated resorcinyl core, which readily decarboxylates by non-enzymatic means12. Structurally, cannabinoids vary by isoprenyl topological arrangement13, of which dicyclic cannabidiol (CBD)-type and tricyclic delta(9)-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC)-type cannabinoids are commonly encountered in planta14. Another important structural feature of cannabinoids is the resorcinyl alkyl side-chain which typically occurs in either pentyl (C5) or to a lesser extent propyl (C3) configuration15,16, although a variety of odd and even carbon lengths have been reported as minor constituents in a subset of germplasm17,18.

The G-protein-coupled cannabinoid type 1 (CB1R) and 2 (CB2R) receptors are principally implicated in mediating biological effects of the human endocannabinoid system, a complex aggregate of several therapeutic targets, multiple signalling pathways and ion channels19,20. The pro-homeostatic functionality of the endocannabinoid system is thought to stem from its secretory regulation of signalling molecules20, namely various neurotransmitters (e.g. 5-HT and GABA)21,22 and cytokines (e.g. TNF-α and IL-17)23,24. Associated neuro-immunomodulatory activity by exogenous cannabinoid ligands appear beneficial in a myriad of seemingly unrelated indications, ranging from the treatment of seizures in refractory paediatric epilepsies (Epidiolex®)25 through to chronic pain in advanced cancer patients (Nabiximols)26. Structure-activity relationship studies have identified the resorcinyl alkyl group as a critical pharmacophoric element27,28. Elongation of the carbon side-chain increases cannabinoid receptor binding affinity29,30, with pharmacological potency of C4 to C8 alkyl chain homologs showing systematic increases up to 29-fold30. Despite the potential for metabolic engineering of the alkyl group for in planta therapeutic cannabinoid portfolio expansion15,31, uncertainty over the genetic and biosynthetic regulation of alkyl cannabinoid homology hinders the development of novel recombinant cannabinoid breeding lines for biopharmaceutical exploitation.

The cannabinoid structural motif is generated from substrates originating from two independent biosynthetic pathways. Aromatic prenylation of geranyl diphosphate (GPP) and a phenolic alkylresorcinolic acid intermediate form monocyclic cannabinoids that feature a linear isoprenyl residue (e.g. cannabigerolic acid (CBGA))32,33. Chain length of the alkylresorcinol fatty acid (FA) starter unit is thought to determine alkyl cannabinoid homology34,35. This hypothesis has been supported using a synthetic cell-free enzymatic platform which produced the propyl-cannabinoid intermediate cannabigerovarinic acid (CBGVA) from a C3 alkylresorcinol substrate (divarinic acid)36. In vivo production of CBGVA and divarinic acid as well as associated end products delta(9)-tetrahydrocannabivarinic acid (THCVA) and cannabidivarinic acid (CBDVA) have also recently been reported in engineered yeast strains fed the predicted C3 alkyl cannabinoid intermediate butanoyl-CoA37. However, resolution of associated in planta biosynthetic pathways has largely focused on C5 alkyl species33,38.

Cannabidiolic acid synthase (CBDAS) and delta(9)-tetrahydrocannabinolic acid synthase (THCAS) perform stereoselective oxidative cyclisation of the isoprenyl moiety, forming dicyclic and tricyclic cannabinoids. Physical and genetic mapping of THCAS and CBDAS genes has recently allowed for alignment of genetic loci to resolve the cluster of closely-linked genes. These genomic regions appeared abundant with retrotransposable elements as well as pseudogenic tandem repeats, and their positions have been assigned within a larger low recombining pericentromeric gene-poor region39,40. Regions also appeared non-homologous between chemotypes which suggests significant divergence between chemotypic lineages, although the reported hemizygosity for THCAS and CBDAS may be an artefact of genome assembly due to the underlying complexity of this region39,40. While the presence of tandem THCAS as well as CBDAS arrays would imply oligogenic inheritance, genepool representative germplasm segregate in a 1:2:1 dicyclic: tricyclic cannabinoid ratio characteristic of a single codominant locus B model41,42. This suggests cannabinoid synthase tandem arrays may include functionally superfluous repeats which seldom recombine, that although separated in terms of physical distance (>1 Mbp)40, segregate in a manner that resembles mutually exclusive BTHCAS (THCAS) and BCBDAS (CBDAS) alleles.

The dioecious reproduction of Cannabis often confounds genetic analysis. Previous analysis of tricyclic chemotypes segregating for alkyl cannabinoid composition inferred a multiple locus A1-A2-… An model, whereby alleles Apr1−n and Ape1−n with additive effect govern the proportion of alkyl cannabinoid homologs31. However, chemotypic continuity of the available progeny precluded demarcation of categories, thereby preventing chi-square analysis to resolve the inheritance model. To examine alkyl cannabinoid loci and determine their allelic assortment with cannabinoid synthase genes, we analysed a population segregating for alkyl and cyclic cannabinoid composition. Biparental reciprocal crosses between chemotypes divergent for alkyl and cyclic cannabinoids were performed, generating F1 hybrid families. A single F2 generation derived from an F1 male and female cross was developed for chemotypic segregation analysis. Cannabinoid profiling of F2 progeny along with genotypic analysis using a THCAS- and CBDAS-specific DNA sequence characterised amplified region (SCAR) marker assay was conducted to investigate interactions between cannabinoid pathway loci. Frequency distributions were determined using kernel density estimation, a statistical method of applying smoothing to a frequency histogram43. Kernel density was used to estimate underlying distributions and to demarcate chemotypes objectively into categories, thereby exposing modes of inheritance for alkyl side-chain length.

Results

Parental selection

Juvenile plants of three parental lines were screened for cannabinoid composition. C3/C5 alkyl cannabinoid fractions (FC3/FC5) associated with alkyl cannabinoid loci (An loci) as well as di-/tri-cyclic cannabinoid fractions (Fdicyclic/Ftricyclic) associated with the B locus complex were determined from the fresh weight (w/w) cannabinoid content of CBDVA, THCVA, cannabidiolic acid (CBDA) and delta(9)-tetrahydrocannabinolic acid (THCA). Eight individual plants which exhibited either [high FC3 + Ftricyclic (e.g. THCVA)] or [high FC5 + Fdicyclic (e.g. CBDA)] cannabinoid chemotypes were tentatively assigned homozygote status at the A and B locus complexes (Table 1). These plants from accessions EIO.MW15.P (n = 4), EIO.MW15.T (n = 2) and EIO.MW17.X (n = 2) were selected as parents to generate two biparental reciprocal crosses, forming four F1 hybrid families (Fig. 1). Parents of F1 hybrid family EIO.MW17.Y1 exhibited the largest divergence in FC3 (Table 1). To further examine parental homozygosity in this lineage, P1 (EIO.MW15.P [07]) and P2 (EIO.MW15.T [02]) were scored using a codominant locus B DNA sequence characterised amplified region (SCAR) marker assay. As expected, P1 and P2 had a marker genotype homozygote for THCAS (BTHCASBTHCAS) and homozygote CBDAS (BCBDASBCBDAS), respectively.

Schematic diagram of filial generations. Parental breeding lines were screened for cannabinoid composition and eight plants high in either FC3 as well as Ftricyclic or FC5 as well as Fdicyclic values served as parents for two biparental reciprocal crosses, generating four F1 hybrid families. A single male and female plant from the F1 hybrid family which demonstrated the highest level of FC3/FC5 homogeneity served as parents of an F2 population segregating for FC3/FC5 and Fdicyclic/Ftricyclic cannabinoid composition. C5 alkyl cannabinoid fraction (FC5); C3 alkyl cannabinoid fraction (FC3); dicyclic cannabinoid fraction (Fdicyclic); and tricyclic cannabinoid fraction (Ftricyclic).

F1 hybrid chemotypic uniformity

F1 individuals across all four hybrid families appeared chemotypically intermediate to the parents, although FC3/FC5 as well as Fdicyclic/Ftricyclic distribution patterns were not uniform between families (Fig. 2a). No consistent maternal or paternal patterns of inheritance were observed for FC3 values among the reciprocal crosses. However, discrete lineage-specific chemotypic distribution patterns were evident, with F1 hybrid families (EIO.MW17.Y1, EIO.MW17.Y2) from EIO.MW15.T parents displaying cannabinoid composition skewed towards high FC5 as well as Fdicyclic values (CBDA) (Fig. 2a,b). Individuals within hybrid families displayed transgressive segregation for a subset of cannabinoids. CBDVA and THCA proportions (%/total) were greater than parent values, with CBDVA increasing by more than 20-fold (Fig. 2b). FC3/FC5 variance differed between the four F1 hybrid families (Table 2), with plants from EIO.MW17.Y1 having the least (Table 2). This, along with the B locus homozygote genotypes of EIO.MW17.Y1 parents, was interpreted as an indication of P1 and P2 homozygosity at the A locus complex. Single male and female plants of EIO.MW17.Y1 were crossed and alkyl cannabinoid segregation assessed in the resulting F2 generation (Fig. 1).

Chemotypic distributions of four F1 hybrid families. (a) Chemotypic distribution patterns of dicyclic and C3 alkyl cannabinoid composition within the total cannabinoid fraction. F1 chemotypes are intermediate to the parents, although discrete linage-specific distribution patterns are evident between families. (b) Compositional range of cannabinoids from individual plants within F1 hybrid families. Blue squares represent chemotypes of individual plants within F1 families; Blue circles represent cannabinoid composition of individual plants within F1 families; Red diamond represent female parent (P1); Black triangle represent male parent (P2); C3 alkyl cannabinoid fraction (FC3); dicyclic cannabinoid fraction (Fdicyclic).

Inheritance patterns of the F2 progeny

A continuous distribution of FC3/FC5 values was observed among the F2 progeny (Fig. 3a,b). To minimise classification error, kernel density estimates (KDE) were used to categorise individual plants objectively prior to testing the fit of genetic models. FC3/FC5 values for the F2 population were non-Gaussian and instead formed discrete pentapartite distributions. FC3/FC5 values were skewed towards low FC3 and deviated significantly from the expected 1:4:6:4:1 chemotypic segregation ratio (Fig. 3a, Table 3). KDE of Fdicyclic/Ftricyclic values formed a predominantly tripartite distribution quasi-compatible with incomplete dominance and a 1:2:1 segregation ratio (Fig. 3b). However, discrete distributions embedded within the intermediate Fdicyclic/Ftricyclic chemotypes suggested the possibility of additional Fdicyclic/Ftricyclic categorises (Fig. 3b). The Fdicyclic/Ftricyclic intermediate chemotypic distribution was skewed towards high Fdicyclic and diverged significantly from the mid-parent Fdicyclic value of 48.5 (Fig. 3b). The continuous distribution of Fdicyclic intermediate and high Fdicyclic values also prevented accurate dissection of inclusion/exclusion boundaries for chemotypic frequency estimation (Fig. 3b).

Chemotypic distribution patterns of F2 progeny segregating for cyclic and alkyl cannabinoid composition. (a) Kernel density estimates of FC3 values showing a pentapartite alkyl cannabinoid distribution. (b) Kernel density estimates of Fdicyclic values showing a predominantly tripartite cyclic cannabinoid distribution. Grid reference points for kernel density estimates for FC3 as well as Fdicyclic values are shown on the x-axes. For FC3 values, frequency distributions are skewed towards low FC3. The intermediate Fdicyclic distribution deviates from the mid-parent value of 48.5 and is skewed towards high Fdicyclic. Red line indicates Fdicyclic mid-parent value; C3 alkyl cannabinoid fraction (FC3); dicyclic cannabinoid fraction (Fdicyclic).

Locus B genotype-specific alkyl cannabinoid distributions

To resolve Fdicyclic/Ftricyclic chemotypic categories, the F2 progeny and F1 parents were genotyped for Fdicyclic (CBDAS) Ftricyclic (THCAS) associated alleles using the locus B DNA SCAR marker assay. The F1 parents had the predicted heterozygote THCAS CBDAS (BTHCASBCBDAS) genotypes. Genotypes BCBDASBCBDAS, BTHCASBCBDAS and BTHCASBTHCAS, were consistent with the Fdicyclic/Ftricyclic chemotype distributions in the F2 progeny (Fig. 4a). On the basis of genotypic frequency, a segregation ratio of 1:2:1 (low, intermediate and high Fdicyclic) characteristic of a codominant monogenic model was accepted (χ2 = 2.65; threshold for accepting H0 at P = 0.05 is 5.99).

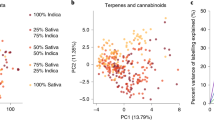

Locus B genotype-specific alkyl cannabinoid distribution patterns within F2 progeny. (a) Cyclic and alkyl cannabinoid inheritance patterns associated with locus B genotypes. (b) Kernel density estimates for homozygote BCBDASBCBDAS genotypes. (c) Kernel density estimates for heterozygote BTHCASBCBDAS genotypes. (d) Kernel density estimates for homozygote BTHCASBTHCAS genotypes. Comparison of Fdicyclic values on the y-axes and FC3 values on the x-axes in Fig. 4a reveal three divergent FC3 inheritance patterns. Locus B genotypes are consistent with Fdicyclic values. C3-alkyl cannabinoid fraction (FC3); dicyclic cannabinoid fraction (Fdicyclic); locus B genotypes: homozygote THCAS (BTHCASBTHCAS), homozygote CBDAS (BCBDASBCBDAS), heterozygote THCAS CBDAS (BTHCASBCBDAS).

Analysis of FC3/FC5 values within locus B genotypes revealed BCBDASBCBDAS-, BTHCASBCBDAS- and BTHCASBTHCAS-specific distribution patterns (Fig. 4a–d, Supplementary Fig. S1). For BCBDASBCBDAS and BTHCASBCBDAS genotypes, quadripartite distributions could be discerned from FC3/FC5 values (Fig. 4b,c). The most obvious deviation from the F2 FC3/FC5 distribution pattern was observed in the BTHCASBTHCAS genotypes, with KDE describing a tripartite distribution (Fig. 4d). Analogous with the complete F2 population (Fig. 3a), BTHCASBCBDAS genotypes had a FC3/FC5 chemotype distribution resembling a composite of locus B homozygote inheritance patterns (Fig. 4b–d).

Given the high frequency of FC3 minima chemotypes among the F2 progeny (Figs 3a, 4b–d), complete dominance at one or more A gene pair locus was considered plausible for FC3/FC5 inheritance. Epistasis was also evaluated for locus B genotype-specific FC3/FC5 segregation ratios due to their non-conformity with Mendelian expectations. For the BCBDASBCBDAS-specific FC3/FC5 quadripartite distribution pattern, a segregation ratio of 9:3:3:1 was accepted in support of a digenic model describing two independent Mendelian loci (Table 3). The BTHCASBTHCAS-specific tripartite FC3/FC5 distribution conformed to a 7:6:3 segregation ratio, and an epistatic model describing dominance at one gene pair and partial dominance at the alternative gene pair was accepted (Table 3). A 9:3:3:1 segregation ratio was not supported by the BTHCASBCBDAS-specific FC3/FC5 values. Given the quadripartite nature of BTHCASBCBDAS-specific FC3/FC5 distributions, a 7:6:3 segregation ratio could not be tested (Table 3). BTHCASBCBDAS-specific FC3 categories I, II and IV did, however, share similar relative frequency and FC3/FC5 spacial distribution as the BTHCASBTHCAS-specific categories (Table 3, Fig. 4c,d).

Discussion

The contiguous pentapartite distributions in the F2 generation for FC3/FC5 values were not consistent with a polygenic binomial inheritance pattern. Quantitative characters are not exclusive to polygenic modes of inheritance44,45. Simple Mendelian inheritance can result in phenotypic continuity when within-genotypic class variation is large and average phenotypic differences between genotypes are negligible45. Given that alkyl-cannabinoid loci are associated with enzymatic reactions which are several biosynthetic steps upstream of the metabolites used for chemotypic assessment46,47, there is potential for intracellular biophysical interactions affecting the channelling and metabolic flux of pathway intermediates. Formation of multienzyme complexes has been implicated in altering isoprenoid production in Arabidopsis thaliana due to physical interactions between geranylgeranyl diphosphate (GGPP) synthase and downstream GGPP-consuming enzymes48. These interactions could affect the expression of alkyl cannabinoids and contribute to the continuous variation in chemotype values observed in filial populations.

The multi-model segregation pattern within the F2 progeny did not support a monogenic model, and so digenic inheritance was considered (Fig. 3a). In a digenic model with additive effects, a segregation ratio of 1:4:6:4:1 is expected49. However, FC3/FC5 values were skewed towards the FC3 minima parent and a disproportionate number of progeny segregated in the FC3 minima category (Fig. 3a, Table 3). Unequal additive effects at different loci associated with the alkyl cannabinoid pathway, combined with aggregation of trigenic heptapartite categories may also have contributed to an F2 chemotype segregation skewed towards the FC3 minima parent, although the frequency of FC3 maxima progeny in category V clearly exceeds the 1/64 allowed by this model (Table 3).

The inheritance of phenotypic traits can be additive or non-additive50. If the inheritance of genes indicates an additive effect, the hybrid phenotype will tend to reflect the average effect of the parent genes or midparent value (MPV)50,51. Phenotypic traits which deviate from the MPV in hybrid progeny are assumed to be inherited in a non-additive manor45,50, and inheritance can be attributed to dominant or epistatic gene effects52. Alkyl cannabinoid proportions within F1 family EIO.MW17.Y1, from which the F2 generation was derived, showed a negative median deviation from the MPV (44.6% FC3), with hybrid progeny displaying a median FC3 value of 35.1 (±6.7 s.d.) (range 24.3–56.0) % (Fig. 2a). Incomplete dominance and/or epistasis may therefore explain the deviation of EIO.MW17.Y1 chemotypes towards the FC3 minima parent (Fig. 2a). A non-additive model may also explain the higher frequency of FC3 minima progeny observed in the F2 generation (Fig. 3a).

Single seed descent F8 recombinant inbred lines as well as doubled haploid lines can achieve more than 99.7% homozygosity53. The parental lines used in the present study were not inbred to this level of homozygosity and parent heterozygosity may have contributed to the non-orthodox F1 and F2 inheritance patterns. Whilst the F1 family EIO.MW17.Y1 were descendants from parents displaying the largest FC3 divergence (Table 1), they also exhibited the highest level of FC3 homogeneity (Table 2), and displayed a uniform monopartite distribution largely consistent with a single category (Figs 2a, 3a). Taken together these factors suggest parental homozygosity at alkyl cannabinoid-determining loci. Given that within-plant C3/C5 alkyl cannabinoid composition has been found to be stable over key developmental stages, environmental and ontogenetic effects are also likely to have contributed minimally to inheritance patterns observed in the filial generations.

Secondary metabolite gene clusters comprising of two or more non-homologous biosynthetic pathway genes have been identified across a number of diverse plant taxa54. A common feature of these clusters is that they contain ‘signature genes’ in addition to other downstream pathway genes54,55,56. Signature genes are often recruited from primary metabolism and encode the first committed biosynthetic steps of the pathway57. For alkyl cannabinoid biosynthesis this is predicted to be the formation of alkylresorcinol fatty acid (FA) starter units35,46,47, which, when incorporated into the resorcinyl skeletal core58, influence directly carbon number of the resulting cannabinoid alkyl side-chain37. While the arrangement of cannabinoid synthesis pathway genes appear to be randomly dispersed over five chromosomes39, the enzymatic basis for cannabinoid FA starter unit synthesis, as well as genomic positioning of associated loci has yet to be established39,46,47,59. Given that cannabinoid synthase loci have been localised to retrotransposon-rich genomic regions compatible with gene cluster formation39,40, it is conceivable that upstream alkyl cannabinoid-determining loci may be physically clustered and/or co-inherited with THCAS and CBDAS genomic intervals.

The contrasting segregation ratios identified in CBDAS (BCBDASBCBDAS) and THCAS (BTHCASBTHCAS) homozygote F2 progeny suggests the possibility of linkage between alkyl and cyclic chemotype-determining loci and may explain the distortion of alkyl cannabinoid ratios from a strictly additive polygenic model (Fig. 4a–d, Table 3). Rearrangement of THCAS and CBDAS genomic regions is evident in the experimental population from the incomplete dominance and irregularity of the intermediate chemotypic distribution (Fig. 3b). Incomplete linkage between the SCAR markers and tandem cannabinoid synthase arrays may have precipitated synthetic genotype-specific inheritance patterns, although uncoupling of the marker with functionally relevant loci is questionable given that genotypes were largely congruent with chemotypic distributions (Fig. 4a). The association of the SCAR marker assay with chemotype has also been established across a range of geographically and genetically divergent Cannabis germplasm60,61.

In vitro feeding studies indicate that THCAS and CBDAS exhibit different catalytic efficiencies towards alkyl homologs62. This could be contributing to genotype-specific segregation patterns, although absence of appreciable levels of CBGA at UV 272 nm in filial FC3 maxima chemotypes would suggest otherwise (Supplementary Fig. S2). The UV profiles of FC5 plants were also dominated by CBDA and/or THCA and no comparable chromatographic peaks with a UV maxima and retention time consistent with CBGVA were observed. Whilst this would infer that cannabinoid synthases are capable of efficiently catalysing CBGA and CBGVA, it is conceivable that the affinity of alkyl homologs to THCAS and CBDAS is influencing the metabolic flux of oxidative cyclisation end-products, and hence the non-Mendelian inheritance patterns observed in filial chemotypes.

In the CBDAS homozygote (BCBDASBCBDAS) F2 genotypes, the 9:3:3:1 ratio could be represented by AC51 and AC52 dominant and Ac31 and Ac32 recessive alleles, with double recessive genotypes Ac31Ac31Ac32Ac32 resulting in FC3 maxima chemotypes. Aliphatic glucosinolate side-chain length in Brassica oleracea is also regulated in a similar manner by independent assortment of GSL-PRO and GSL-ELONG63. The 7:6:3 ratio identified in THCAS homozygote F2 genotypes describes a more complex model, with dominance at one gene pair, and partial dominance at a second gene pair64. When homozygous recessive (Ac51 Ac51), the first gene pair is epistatic to the second gene pair64. Interestingly, a tripartite FC3/FC5 alkyl cannabinoid distribution was also identified from cluster analysis of a diversity panel comprised of predominantly tricyclic cannabinoid chemotypes15.

One speculative scenario to describe the aforementioned epistatic model is that THCAS co-inherited alkyl cannabinoid loci encode sequential interdependent enzymatic steps65,66 (Fig. 5). De novo short-chain FA synthesis in planta is dependent on a series of enzymatic reactions involving β-ketoacyl-ACP synthase, β-ketoacyl-ACP reductase, β-hydroxyacyl-ACP dehydrase as well as enoyl-ACP reductase67, followed by thioesterase hydrolysis to terminate synthesis68. The dominant AC31 allele at the first gene pair may govern one of four condensing, reductase or dehydrase reactions which contribute towards FA chain length69, resulting in increased production of butanoyl-ACP (Fig. 5). AC32 at the second gene pair could encode a thioesterase with high catalytic efficiency (kcat) towards butanoyl-ACP, thereby allowing FA plastid exportation of butanoic acid for downstream cytosolic-localised alkylresorcinol synthesis47,68 (Fig. 5). The AC32 modifier would act only on butanoyl-ACP and when homozygous recessive for Ac51, FA synthesis would be exclusive to the C5 alkyl cannabinoid precursor hexanoic acid (Fig. 5).

Speculative digenic epistatic model governing alkyl cannabinoid composition in THCAS homozygote plants. The dominant AC31 allele at the first gene pair governs one of four condensing, reductase or dehydrase reactions forming butanoyl-ACP. The partially dominant allele AC32 at the second gene pair encodes an acyl-ACP thioesterase with high catalytic efficiency (kcat) for butanoyl-ACP. The acyl-ACP thioesterase allows plastid exportation of butanoic acid for cytosolic-localised alky cannabinoid biosynthesis. The homozygous recessive genotype (Ac51 Ac51) at the first gene pair results in the exclusive production of hexanoic acid and is epistatic to the second gene pair encoding the 4:0-ACP thioesterase; acyl activating enzyme (AAE); acyl-acyl carrier protein (ACP); cannabidiolic acid synthase (CBDAS); cannabidivarinic acid (CBDVA); cannabigerovarinic acid (CBGVA); divarinolic acid (DA); fatty acid (FA); geranyl pyrophosphate (GPP); olivetolic acid cyclase (OAC); prenyltransferase (PT); delta(9)-tetrahydrocannabinolic acid synthase (THCAS); delta(9)-tetrahydrocannabivarinic acid (THCVA); tetraketide synthase (TKS); C5 alkyl cannabinoid fraction (FC5); C3 alkyl cannabinoid fraction (FC3).

Previous analysis of six S1 to S6 inbred lines segregating for tricyclic C3 and C5 alkyl cannabinoids revealed a variety of lineage-specific distribution patterns31. A polygenic inheritance model was inferred from the absence of 100% ‘pure’ C3-alkly cannabinoid chemotypes as well as from the mutual crossing of lineages increasing C3 alkyl cannabinoid proportion from 85.5–95.6%31. In the present study, digenic inheritance patterns were adequate to explain FC3 values ranging from 0.7–88.0% (Table 1, Fig. 4a).

Absence of FC3 transgressive segregation or plants displaying FC3 values > 90% suggests a chemotypic plateau has been reached in the experimental population (Table 1), and that parental genes lack a complementary additive effect on FC3 values70. A number of enzymatic reactions occur prior to oxidative cyclisation by THCAS and CBDAS. These involve a series of steps leading to FA formation in addition to acyl activation47, two-step polyketide synthesis38 and aromatic prenylation33 (Fig. 5), of which a minimum of two catalytic steps were found to be allelic and determinant of chemotype (Table 3, Fig. 4b,d). Analysis of cannabinoid biosynthesis in engineered yeast indicates that acyl activation, polyketide synthesis and aromatic prenylation steps are catalysed by promiscuous enzymes, with recombinant pathway proteins capable of producing a variety of alkyl homologs based on the type of FA starter unit fed37. Assuming cannabinoid pathway loci are allelic and encode enzymes with varying levels of promiscuity37, gene-flow at these loci may confer an additive or epistatic effect and a polygenic alkyl cannabinoid inheritance model may be correct. However, with consideration of measurement error and environmental deviation15,71, the lineage-specific gene effects reported from mutual crossing may only be marginal.

Regardless of the total number of loci contributing to alkyl-cannabinoid composition, inheritance patterns reported here and elsewhere suggest the partitioning of allelic variation among lineages31. Inter-lineage genetic heterogeneity has the potential to confound elucidation of the genetic architecture underlying alkyl cannabinoid composition when using forward genetic approaches. Quantitative Trait Locus (QTL) mapping may only capture a subset of inter-lineage allelic diversity and associated epistasis in natural populations72, while in Genome Wide Association Studies (GWAS), genetic heterogeneity among lineages reduces the power to detect causal variants73,74. In these cases, synthetic and/or ancestral marker loci may be more predictive of phenotype when two or more gene mutations have a comparable phenotypic effect74. Given that lineage-specific evolutionary processes are implicated at cannabinoid pathway loci40, comparative genomic approaches using representative germplasm may precipitate diagnostically valuable chemotype-associated markers while also potentially delineating candidate alkyl cannabinoid loci for genome engineering8.

The analysis of filial chemotypes was targeted towards variation in alkyl side-chain length. Whilst this analysis improved understanding of the heritability of cannabinoid homology, much remains to be examined. In addition to variation in the topological arrangement of the isoprenoid residue13, prenylogous versions of cannabinoids have been identified in the form of sesquicannabigerol75. This degree of isoprenylation improved pharmacological potency towards CB2R and it is possible that other medically relevant cannabinoid prenylogues may exist75. Further non-targeted cannabinomic analyses, combined with forward genetic screens, may further elucidate the molecular basis for cannabinoid homology and ultimately expand the number of therapeutics which can be produced in planta.

In conclusion, the inheritance of alkyl cannabinoid composition and associated allelic assortment with THCAS and CBDAS was examined. Digenic segregation patterns observed in cannabinoid synthase genotypes suggests a complex mode of inheritance for alkyl side-chain length involving epistasis, linkage as well as dominant and lineage-specific gene effects. Linking plant secondary metabolites to underlying biosynthetic genes and associated regulatory networks remains challenging and often requires a multifaceted approach76,77. Comparative genomic approaches may contribute to understanding of the molecular basis for alkyl cannabinoid composition and shed light on the recruitment and evolution of pathway genes. Advances in understanding of the inheritance and biosynthesis of the alkyl pharmacophore may also allow for metabolic engineering of Cannabis to accelerate development of novel efficacious plant-derived cannabinoid homologs with augmented therapeutic activities.

Methods

Genetic resources and cultivation

Acquisition and storage of research materials and associated experimental procedures were conducted under the provisions of the Drug Misuse and Trafficking Act 1985 and in accordance with authorisations granted to Professor Graham King by the New South Wales Ministry of Health, Pharmaceutical Regulatory Unit, Legal and Regulatory Services Branch, Australia. Three Cannabis sativa L. seed pack accessions EIO.MW15.P, EIO.MW15.T and EIO.MW17.X associated with either high C3 alkyl (FC3) tricyclic (Ftricyclic) or high C5 alkyl (FC5) dicyclic (Fdicyclic) compositions were sourced from the Ecofibre Industries Operations Pty Ltd Global Germplasm Collection (EFGGC) (Table 1).

Twenty seeds per accession were sown into 400 mL round pots at a depth of 1.5 cm. Each pot contained a growing medium containing one-part vermiculite, one-part perlite and one-part peat moss, as well as dolomite (110 g/100 L). Pots were watered daily and supplemented with CANNA® Aqua Vega nutrient solution post germination upon full extension of the first leaflet pair. Seedlings were grown indoors within bespoke pollen secure growth chambers and grown under an 11 h photoperiod using high pressure sodium (HPS) and metal halide (MH) lighting (luminous flux = 72,000 lumens). At the flower primordia stage (code 2001)78, selected plants were transferred into single 8 L pots containing 100 g Osmocote® Exact slow release nutrient mix and 8 g of Micromax® micronutrient formula. Optimal water regimes were controlled using automatic ‘smart valves’ and temperature was maintained between 26 and 28 °C.

Experimental populations

Individual plants from accessions EIO.MW15.P (n = 22), EIO.MW15.T (n = 18), EIO.MW17.X (n = 13) were screened for chemotype using LC-MS cannabinoid profiling at the vegetative stage (code 1008)78 (Table 1). Plants which exhibited high FC3 and Ftricyclic (e.g. THCVA) or high FC5 and Fdicyclic (e.g. CBDA) cannabinoid values were selected for crossing (Table 1, Fig. 1). Sex was provisionally phenotyped from visual inspection during the flower primordia developmental stage prior to male anthesis (code 2001)78. Plant vigour was also considered during selection. Eight chemotypically extreme male and female plants high in THCVA (EIO.MW15.P) or CBDA (EIO.MW15.T and EIO.MW17.X) served as parents for four F1 hybrid families, which were generated from two biparental reciprocal crosses (Table 1, Fig. 1). Generation of 210 F2 progeny was achieved by crossing a single male and female plant from the F1 hybrid family which exhibited the highest level of FC3 chemotypic homogeneity. Biparental crosses were performed within pollen secure growth chambers. Pollination of female plants was achieved through exposure to male plants during anthesis.

LC-MS chemotyping

Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) cannabinoid profiling and extraction of individual plants followed methodologies described by Welling et al.15. At the vegetative stage (fourth leaf pair, code 1008)78, two × 250 mg fresh leaf material was taken from the sub-apical raceme at opposing phyllotaxis. Plant material was transferred to a 2 mL Eppendorf® Safe-Lock microcentrifuge tubes containing a 3 mm Qiagen Tungsten Carbide Bead and frozen using liquid nitrogen. Plant tissue was disrupted using a Qiagen TissueLyser® by agitation at 30 rotations per sec for 60 s. Plant tissue was vortexed in 1 mL of high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) grade EtOH and mixed by agitation for 30 min. Extracts were centrifuged to remove particulate matter and 600 μL of the supernatant was transferred into a 2 mL screw cap glass vial.

LC-MS runs were performed using an Agilent 1290 Infinity analytical HPLC instrument (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA, United States), which comprised of a vacuum degasser, autoinjector, binary pump and diode array detector (DAD, 1260), coupled to an Agilent 6120 Single Quadrupole Mass Selective Detector (MSD). Analytical infrastructure was controlled using ChemStation (Agilent) software (Rev. B.04.03 [54]). A C18 Agilent Eclipse plus rapid resolution high definition column (1.8 μm; 50 mm × 2.1 mm internal diameter) was used. Absorbance was monitored at 210, 214, 272, 280, 330 and 360 nm.

The mobile phase consisted of a mixture of Milli-Q® water (channel A) and acetonitrile (channel B) containing 0.005% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA). The initial setting was isocratic at 66% B for 8 min, which was linearly increased to 95% B over 4 min. 95% B was maintained for 1 min and then re-equilibrated to 66% B for 2 min. Total run time including an internal needle wash was 16 min. Flow rate was 0.3 mL/min. Column temperature was set to 30 °C. Injection volume was 3 μL. The MSD was run in atmospheric pressure electrospray ionisation mode (AP-ESI). Selected-ion monitoring (SIM) was used for cannabinoid quantification, with abundant and representative signals obtained in positive mode [M + H]+ 15; drying gas temperature, 350 °C; capillary voltage, 3000 V (positive); vaporiser temperature, 350 °C; drying gas flow, 12 L/min (N2); nebuliser pressure, 35 psi; scan mass range, 100–1200; fragmentor, 150.

Cannabinoid standards cannabinol (CBN), CBGA, cannabigerol (CBG), cannabidiolic acid (CBDA), CBD, cannabidivarin (CBDV), cannabichromene (CBC), delta(9)-tetrahydrocannabinolic acid (THCA), THC, and delta(9)-tetrahydrocannabivarin (THCV) were sourced from Novachem Pty Ltd. (Melbourne, VIC, Australia). THCVA and CBDVA were developed in-house using an Agilent 1260 Infinity preparative HPLC system, with purified fractions structurally elucidated using a Bruker Avance III HDX 800 MHz spectrometer15. Calibration solutions for acidic as well as neutral reference cannabinoids were prepared at 100, 20, 4, 0.8, 0.16, 0.032 μg/mL and calibration curves for each cannabinoid were linear across the calibration range (r2 > 0.99). Precision was determined by injecting stock solutions six times and monitoring cannabinoid peak area (relative standard deviation (RSD) < 2%). Interday MSD variability was minimised by running calibration curves every 48 hours. Data acquisition and analysis was performed using Agilent ChemStation© (Rev. B.04.03 [54]) software.

Locus B DNA SCAR marker

Plant DNA was extracted using a Qiagen DNeasy® Plant Mini Kit, with tissue disruption achieved using a Qiagen TissueLyser®. DNA purity was assessed using a ThermoScientificTM NanoDropTM 2000 UV–vis spectrophotometer. An absorbance ratio of ~1.8 at 260/280 nm and symmetric peaks at 260 nm were used to determine DNA quality.

Amplification of CBDAS (B1080) and THCAS (B1190) sequence characterised amplified region (SCAR) fragments was accomplished using a B locus-specific multiplex PCR assay comprising of three primers: a primer common to CBDAS and THCAS FW: 5′ AAGAAAGTTGGCTTGCAG 3′ as well as a CBDAS-specific REV: 5′ ATCCAGTTTAGATGCTTTTCGT 3′ and a THCAS-specific REV: 5′ TTAGGACTCGCATGATTAGTTTTTC 3′ primer60,79.

PCR parameters followed those described by Welling et al.61. Reactions were performed in 0.2 mL 96 well PCR plates in a total volume of 50 µL and contained 1.5 mM of MgCl2, 0.2 mM of dNTPs, 0.4 µM of the forward primer, 0.2 µM of the THCAS- as well as the CBDAS-specific reverse primers, and 2 U of Life Technologies Platinum® Taq DNA Polymerase. Thermocycling parameters for the DNA template were as follows: 94 °C for 2 min, followed by 25 cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, 58 °C for 30 s, 72 °C for 1 min 15 s. No final extension was required. CBDAS- and THCAS-specific fragments were then separated using electrophoresis with a 1% SeaKem® LE agarose gel stained with GelRedTM. Amplicons were visualised under UV illumination with a Bio-Rad Molecular Imager® Gel DocTM XR + system using Image LabTM software.

Statistical analysis

CBDVA, THCVA, CBDA, THCA, CBDV, THCV, CBD and THC fresh weight (w/w) content was determined per plant. Relative proportions of these cannabinoids was used to generate C3 alkyl (FC3), C5 alkyl (FC5), dicyclic (Fdicyclic) and tricyclic (Ftricyclic) cannabinoid fractions within the total cannabinoid fraction. To minimise post-harvest alteration of cannabinoid composition, decarboxylated cannabinoids CBDV, THCV, CBD and THC were expressed as carboxylated acid (COOH) cannabinoids using formulae which compensate for changes in molecular weight15. Repeatability between LC-MS replicate extractions were calculated using coefficient of determination (r2). Strong correlations between duplicate extraction replicates were found for the FC3/FC5 (r2 > 0.99) as well as for the Fdicyclic/Ftricyclic (r2 > 0.99) values. Mean extraction replicate values were therefore used for statistical analysis.

Alkyl cannabinoid data from the F2 generation was visualised in a graphical format used previously31 (Supplementary Fig. S3). Analysis of F2 chemotypic distribution patterns revealed stepwise increases in FC3 values, although accurate demarcation of data points was not possible (Supplementary Fig. S3). Histograms were then developed to establish frequency distributions for categorisation (Supplementary Fig. S3). However, the continuity of chemotype prevent formation of obvious break points in the data (Supplementary Fig. S3). The arbitrary selection of bins was also deemed inappropriate for determining distributions due to the potential for incorrect assignment of genotype (classification error). To address these issues, kernel density was used to estimate the unknown underlying distributions within the data. This constructed an estimate of the density function from observations within the data43, generating a fitted solid line over the FC3 value data points (Supplementary Fig. S3). The area under kernel density estimates (KDE) was then used to demarcate FC3 values and to objectively categorise plants (Supplementary Fig. S3), circumventing arbitrary categorisation and the artificial grouping of FC3 values.

GenStat 64-bit Release 18.1 (VSN International Ltd.) software was used to calculate Bartlett’s test for homogeneity of variances, KDE and Pearson’s chi-squared (χ2) goodness-of-fit. For KDE, automatic estimation of the bandwidth h was achieved using the method proposed by Sheather and Jones80. Kernels supported by a frequency of n = 1 were not considered. Categorisation frequencies for Pearson’s χ2 goodness-of-fit were obtained by baseline peak integration of KDE, which provided chemotypic grid point inclusion/exclusion boundaries (Supplementary Fig. S3).

Data Availability

The LC-MS datasets derived from experimental populations generated and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Zhang, Q. et al. Latitudinal adaptation and genetic insights into the origins of Cannabis sativa L. Front. Plant Sci. 9, 1876, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2018.01876 (2018).

Soler, S. et al. Genetic structure of Cannabis sativa var. indica cultivars based on genomic SSR (gSSR) markers: implications for breeding and germplasm management. Ind. Crops Prod. 104, 171–178, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2017.04.043 (2017).

Small, E. & Cronquist, A. A practical and natural taxonomy for Cannabis. Taxon 25, 405–435, https://doi.org/10.2307/1220524 (1976).

Mandolino, G. & Carboni, A. Potential of marker-assisted selection in hemp genetic improvement. Euphytica 140, 107–120, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10681-004-4759-6 (2004).

Chandra, S., Lata, H., ElSohly, M. A., Walker, L. A. & Potter, D. Cannabis cultivation: methodological issues for obtaining medical-grade product. Epilepsy Behav. 70, 302–312, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yebeh.2016.11.029 (2017).

Small, E. & Naraine, S. G. Size matters: evolution of large drug-secreting resin glands in elite pharmaceutical strains of Cannabis sativa (marijuana). Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 63, 349–359, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10722-015-0254-2 (2015).

Zhou, X. et al. Early agricultural development and environmental effects in the Neolithic Longdong basin (eastern Gansu). Chin. Sci. Bull. 56, 762, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11434-010-4286-x (2011).

Welling, M. T. et al. A belated green revolution for Cannabis: virtual genetic resources to fast-track cultivar development. Front. Plant Sci. 7, 1113, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2016.01113 (2016).

Hanuš, L. O. et al. Enantiomeric cannabidiol derivatives: synthesis and binding to cannabinoid receptors. Org. Biomol. Chem. 3, 1116–1123, https://doi.org/10.1039/B416943C (2005).

Gertsch, J., Pertwee, R. G. & Di Marzo, V. Phytocannabinoids beyond the Cannabis plant–do they exist? Br. J. Pharmacol. 160, 523–529, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00745.x (2010).

Happyana, N. et al. Analysis of cannabinoids in laser-microdissected trichomes of medicinal Cannabis sativa using LCMS and cryogenic NMR. Phytochemistry 87, 51–59, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phytochem.2012.11.001 (2013).

Dussy, F. E., Hamberg, C., Luginbühl, M., Schwerzmann, T. & Briellmann, T. A. Isolation of Δ9-THCA-A from hemp and analytical aspects concerning the determination of Δ9-THC in Cannabis products. Forensic Sci. Int. 149, 3–10, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forsciint.2004.05.015 (2005).

Hanuš, L. O., Meyer, S. M., Muñoz, E., Taglialatela-Scafati, O. & Appendino, G. Phytocannabinoids: a unified critical inventory. Nat. Prod. Rep. 33, 1357–1392, https://doi.org/10.1039/c6np00074f (2016).

Hazekamp, A., Tejkalová, K. & Papadimitriou, S. Cannabis: from cultivar to chemovar II-a metabolomics approach to Cannabis classification. Cannabis Cannabinoid Res. 1, 202–215, https://doi.org/10.1089/can.2016.0017 (2016).

Welling, M. T., Liu, L., Raymond, C. A., Ansari, O. & King, G. J. Developmental plasticity of the major alkyl cannabinoid chemotypes in a diverse Cannabis genetic resource collection. Front. Plant Sci. 9, 1510, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2018.01510 (2018).

Hillig, K. W. & Mahlberg, P. G. A chemotaxonomic analysis of cannabinoid variation in Cannabis (Cannabaceae). Am. J. Bot. 91, 966–975, https://doi.org/10.3732/ajb.91.6.966 (2004).

Vree, T., Breimer, D., Ginneken, C. & Rossum, J. Identification in hashish of tetrahydrocannabinol, cannabidiol and cannabinol analogues with a methyl side‐chain. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 24, 7–12, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2042-7158.1972.tb08857.x (1972).

Smith, R. Identification of butyl cannabinoids in marijuana. J. Forensic Sci. 42, 610–618, https://doi.org/10.1520/JFS14173J (1997).

Di Marzo, V. New approaches and challenges to targeting the endocannabinoid system. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 17, 623–639, https://doi.org/10.1038/nrd.2018.115 (2018).

Toczek, M. & Malinowska, B. Enhanced endocannabinoid tone as a potential target of pharmacotherapy. Life Sci. 204, 20–45, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lfs.2018.04.054 (2018).

Muntoni, A. L. et al. Cannabinoids modulate spontaneous neuronal activity and evoked inhibition of locus coeruleus noradrenergic neurons. Eur. J. Neurosci. 23, 2385–2394, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.04759.x (2006).

Moranta, D., Esteban, S. & García-Sevilla, J. A. Differential effects of acute cannabinoid drug treatment, mediated by CB 1 receptors, on the in vivo activity of tyrosine and tryptophan hydroxylase in the rat brain. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 369, 516–524, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00210-004-0921-x (2004).

Cencioni, M. T. et al. Anandamide suppresses proliferation and cytokine release from primary human T-lymphocytes mainly via CB2 receptors. PloS One 5, e8688, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0008688 (2010).

Murai, M. et al. SA13353 (1-[2-(1-adamantyl) ethyl]-1-pentyl-3-[3-(4-pyridyl) propyl] urea) inhibits TNF-α production through the activation of capsaicin-sensitive afferent neurons mediated via transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 in vivo. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 588, 309–315, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejphar.2008.04.037 (2008).

Thiele, E. A. et al. Cannabidiol in patients with seizures associated with Lennox-Gastaut syndrome (GWPCARE4): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet 391, 1085–1096, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30136-3 (2018).

Lichtman, A. H. et al. Results of a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study of nabiximols oromucosal spray as an adjunctive therapy in advanced cancer patients with chronic uncontrolled pain. J. Pain Symptom Manage. 55, 179–188. e171, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2017.09.001 (2018).

Prandi, C., Blangetti, M., Namdar, D. & Koltai, H. Structure-activity relationship of cannabis derived compounds for the treatment of neuronal activity-related diseases. Molecules 23, 1526, https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules23071526 (2018).

Thakur, G. A., Duclos, R. I. & Makriyannis, A. Natural cannabinoids: templates for drug discovery. Life Sci. 78, 454–466, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lfs.2005.09.014 (2005).

Razdan, R. K. Structure-activity relationships in cannabinoids. Pharmacol. Rev. 38, 75–149 (1986).

Martin, B. et al. Manipulation of the tetrahydrocannabinol side chain delineates agonists, partial agonists, and antagonists. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 290, 1065–1079 (1999).

De Meijer, E. P. M. & Hammond, K. M. The inheritance of chemical phenotype in Cannabis sativa L. (V): regulation of the propyl-/pentyl cannabinoid ratio, completion of a genetic model. Euphytica 210, 291–307, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10681-016-1721-3 (2016).

Fellermeier, M., Eisenreich, W., Bacher, A. & Zenk, M. H. Biosynthesis of cannabinoids: incorporation experiments with 13C‐labeled glucoses. Eur. J. Biochem. 268, 1596–1604, https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1432-1327.2001.02030.x (2001).

Page, J. E. & Boubakir, Z. Aromatic prenyltransferase from Cannabis. (2011).

Cook, D. et al. Alkylresorcinol synthases expressed in Sorghum bicolor root hairs play an essential role in the biosynthesis of the allelopathic benzoquinone sorgoleone. Plant Cell 22, 867–887, https://doi.org/10.1105/tpc.109.072397 (2010).

Flores-Sanchez, I. J. & Verpoorte, R. Secondary metabolism in cannabis. Phytochem. Rev. 7, 615–639, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11101-008-9094-4 (2008).

Valliere, M. A. et al. A cell-free platform for the prenylation of natural products and application to cannabinoid production. Nat. Commun. 10, 565, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-08448-y (2019).

Luo, X. et al. Complete biosynthesis of cannabinoids and their unnatural analogues in yeast. Nature 567, 123–126, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-019-0978-9 (2019).

Gagne, S. J. et al. Identification of olivetolic acid cyclase from Cannabis sativa reveals a unique catalytic route to plant polyketides. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109, 12811–12816, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1200330109 (2012).

Laverty, K. U. et al. A physical and genetic map of Cannabis sativa identifies extensive rearrangements at the THC/CBD acid synthase loci. Genome Res. 29, 146–156, https://doi.org/10.1101/gr.242594.118 (2019).

Grassa, C. J. et al. A complete Cannabis chromosome assembly and adaptive admixture for elevated cannabidiol (CBD) content. BioRxiv, https://doi.org/10.1101/458083 (2018).

De Meijer, E. P. M. et al. The inheritance of chemical phenotype in Cannabis sativa L. Genetics 163, 335–346, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10681-005-1164-8 (2003).

Weiblen, G. D. et al. Gene duplication and divergence affecting drug content in Cannabis sativa. New Phytol. 208, 1241–1250, https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.13562 (2015).

Silverman, B. W. Density estimation for statistics and data analysis. (Routledge, 2018).

Zhang, T., Jia, X. & Xu, Z. The limitations of polygenic hypothesis and theorizing about dual multiple factors and three normal distributions. Appl. Math. 7, 912–919, https://doi.org/10.4236/am.2016.79081 (2016).

Griffiths, A., Gelbart, W., Miller, J. & Lewontin, R. Modern genetic analysis. (WH Freeman, 1999).

Marks, M. D. et al. Identification of candidate genes affecting Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol biosynthesis in Cannabis sativa. J. Exp. Bot. 60, 3715–3261, https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/erp210 (2009).

Stout, J. M., Boubakir, Z., Ambrose, S. J., Purves, R. W. & Page, J. E. The hexanoyl-CoA precursor for cannabinoid biosynthesis is formed by an acyl-activating enzyme in Cannabis sativa trichomes. Plant J. 71, 353–365, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-313X.2012.04949.x (2012).

Ruiz‐Sola, M. Á. et al. Arabidopsis geranylgeranyl diphosphate synthase 11 is a hub isozyme required for the production of most photosynthesis‐related isoprenoids. New Phytol. 209, 252–264, https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.13580 (2016).

Erickson, E., Wilcox, J. & Cavins, J. Inheritance of altered palmitic acid percentage in two soybean mutants. J. Hered. 79, 465–468, https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.jhered.a110552 (1988).

Chen, Z. J. Genomic and epigenetic insights into the molecular bases of heterosis. Nat. Rev. Genet. 14, 471, https://doi.org/10.1038/nrg3503 (2013).

Cubillos, A. E. R. et al. Inheritance patterns in metabolism and growth in diallel crosses of Arabidopsis thaliana from a single growth habitat. Heredity 120, 463, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41437-017-0030-5 (2018).

Oakey, H., Verbyla, A., Pitchford, W., Cullis, B. & Kuchel, H. Joint modeling of additive and non-additive genetic line effects in single field trials. Theor Appl GenetTheoretical and Applied Genetics 113, 809–819, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00122-006-0333-z (2006).

Seymour, D. K. et al. Rapid creation of Arabidopsis doubled haploid lines for quantitative trait locus mapping. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109, 4227–4232, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1117277109 (2012).

Boycheva, S., Daviet, L., Wolfender, J.-L. & Fitzpatrick, T. B. The rise of operon-like gene clusters in plants. Trends Plant Sci. 19, 447–459, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tplants.2014.01.013 (2014).

Nützmann, H. W., Huang, A. & Osbourn, A. Plant metabolic clusters–from genetics to genomics. New Phytol. 211, 771–789, https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.13981 (2016).

Osbourn, A. Secondary metabolic gene clusters: evolutionary toolkits for chemical innovation. Trends Genet. 26, 449–457, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tig.2010.07.001 (2010).

Hamberger, B. & Bak, S. Plant P450s as versatile drivers for evolution of species-specific chemical diversity. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond., B, Biol. Sci. 368, 20120426, https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2012.0426 (2013).

Suzuki, Y., Kurano, M., Esumi, Y., Yamaguchi, I. & Doi, Y. Biosynthesis of 5-alkylresorcinol in rice: incorporation of a putative fatty acid unit in the 5-alkylresorcinol carbon chain. Bioorg. Chem. 31, 437–452, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bioorg.2003.08.003 (2003).

Van Bakel, H. et al. The draft genome and transcriptome of Cannabis sativa. Genome Biol. 12, R102, https://doi.org/10.1186/gb-2011-12-10-r102 (2011).

Onofri, C., de Meijer, E. P. M. & Mandolino, G. Sequence heterogeneity of cannabidiolic- and tetrahydrocannabinolic acid-synthase in Cannabis sativa L. and its relationship with chemical phenotype. Phytochemistry 116, 57–68, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phytochem.2015.03.006 (2015).

Welling, M., Liu, L., Shapter, T., Raymond, C. & King, G. Characterisation of cannabinoid composition in a diverse Cannabis sativa L. germplasm collection. Euphytica 208, 463–475, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10681-015-1585-y (2016).

Shoyama, Y., Hirano, H. & Nishioka, I. Biosynthesis of propyl cannabinoid acid and its biosynthetic relationship with pentyl and methyl cannabinoid acids. Phytochemistry 23, 1909–1912, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0031-9422(00)84939-0 (1984).

Li, G., Riaz, A., Goyal, S., Abel, S. & Quiros, C. Inheritance of three major genes involved in the synthesis of aliphatic glucosinolates in Brassica oleracea. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 126, 427–431, https://doi.org/10.21273/JASHS.126.4.427 (2001).

Miko, I. In Nature Education Vol. 1 197 (2008).

Nadeau, J. H. Modifier genes in mice and humans. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2, 165–174, https://doi.org/10.1038/35056009 (2001).

Cheema, J., Faraldos, J. A. & O’Maille, P. E. Epistasis and dominance in the emergence of catalytic function as exemplified by the evolution of plant terpene synthases. Plant Sci. 255, 29–38, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plantsci.2016.11.006 (2017).

Marchive, C., Nikovics, K., To, A., Lepiniec, L. & Baud, S. Transcriptional regulation of fatty acid production in higher plants: molecular bases and biotechnological outcomes. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 116, 1332–1343, https://doi.org/10.1002/ejlt.201400027 (2014).

Salas, Jn. J. & Ohlrogge, J. B. Characterization of substrate specificity of plant FatA and FatB acyl-ACP thioesterases. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 403, 25–34, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0003-9861(02)00017-6 (2002).

Leonard, J. M., Knapp, S. J. & Slabaugh, M. B. A Cuphea β‐ketoacyl‐ACP synthase shifts the synthesis of fatty acids towards shorter chains in Arabidopsis seeds expressing Cuphea FatB thioesterases. Plant J. 13, 621–628, https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-313X.1998.00066.x (1998).

Rick, C. M. & Smith, P. G. Novel variation in tomato species hybrids. Am. Nat. 87, 359–373, https://doi.org/10.1086/281796 (1953).

Geiler-Samerotte, K. et al. The details in the distributions: why and how to study phenotypic variability. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 24, 752–759, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copbio.2013.03.010 (2013).

Symonds, V. V. et al. Mapping quantitative trait loci in multiple populations of Arabidopsis thaliana identifies natural allelic variation for trichome density. Genetics 169, 1649–1658, https://doi.org/10.1534/genetics.104.031948 (2005).

Manchia, M. et al. The impact of phenotypic and genetic heterogeneity on results of genome wide association studies of complex diseases. PloS One 8, e76295, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0076295 (2013).

Korte, A. & Farlow, A. The advantages and limitations of trait analysis with GWAS: a review. Plant Methods 9, 29, https://doi.org/10.1186/1746-4811-9-29 (2013).

Pollastro, F. et al. Bioactive prenylogous cannabinoid from fiber hemp (Cannabis sativa). J Nat. Pro. 74, 2019–2022, https://doi.org/10.1021/np200500p (2011).

Jiang, J. et al. VvWRKY8 represses stilbene synthase genes through direct interaction with VvMYB14 to control resveratrol biosynthesis in grapevine. J. Exp. Bot. 70, 715–729, https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/ery401 (2018).

Chen, W. et al. Genome-wide association analyses provide genetic and biochemical insights into natural variation in rice metabolism. Nat. Genet. 46, 714–721, https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.3007 (2014).

Mediavilla, V., Jonquera, M., Schmid-Slembrouck, I. & Soldati, A. Decimal code for growth stages of hemp (Cannabis sativa L.). J. Int. Hemp Assoc. 5, 68–74 (1998).

Pacifico, D. et al. Genetics and marker-assisted selection of the chemotype in Cannabis sativa L. Mol. Breed. 17, 257–268, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11032-005-5681-x (2006).

Sheather, S. J. & Jones, M. C. A reliable data-based bandwidth selection method for kernel density estimation. J. R. Stat. Soc. Series B Stat. Methodol. 53, 683–690, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2517-6161.1991.tb01857.x (1991).

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge Ecofibre Pty Ltd. for allowing Southern Cross University access to the Ecofibre Global Germplasm Collection and for providing valuable information relevant to the selection of accessions. The authors would also like to acknowledge the material and financial support provided by Ecofibre.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.W. prepared the manuscript, designed and performed experiments, including the development of experimental populations as well as chemical and genetic analysis. L.L. contributed to the development of analytical procedures and performed detailed review and revision of the manuscript. C.R. performed statistical analyses as well as review and revision of the manuscript. T.K. contributed to the analysis of chemotypes as well as review and revision of the manuscript. O.A. provided background information and performed review and revision of the manuscript. G.K. provided substantial contributions to conception and design of the research project and performed detailed review and revision of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

Southern Cross University receives funding from the commercial entity Ecofibre Pty Ltd. Ananda Hemp Ltd are a subsidiary company of Ecofibre. Matthew Welling received a stipend from Ecofibre. Omid Ansari is an employee of Ecofibre. Lei Liu, Carolyn A. Raymond, Tobias Kretzschmar and Graham J. King declare no potential conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Welling, M.T., Liu, L., Raymond, C.A. et al. Complex Patterns of Cannabinoid Alkyl Side-Chain Inheritance in Cannabis. Sci Rep 9, 11421 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-47812-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-47812-2

This article is cited by

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.