Abstract

We report the novel tunability of the diameters and spacings of paired Ge double quantum dots (DQDs) using nano-spacer technology in combination with selective oxidation of Si0.85Ge0.15 at high temperature. Pairs of spherical-shaped Ge QDs were formed by the selective oxidation of poly-SiGe spacer islands at each sidewall corner of the nano-patterned Si3N4/poly-Si ridges. The diameters of the Ge spherical QDs are essentially determined by geometrical conditions (height, width, and length) of the nano-patterned spacer islands of poly-SiGe, which are tunable by adjusting the process times of deposition and etch back for poly-SiGe spacer layers in combination with the exposure dose of electron-beam lithography. Most importantly, the separations between the Ge DQDs are controllable by adjusting the widths of the poly-Si/Si3N4 ridges and the thermal oxidation times. Our self-organization and self-alignment approach achieved high symmetry within the Ge DQDs in terms of the individual QD diameters as well as the coupling barriers between the QDs and external electrodes in close proximity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Quantum computing requires scalable quantum bits (qubits) that have to be controllably located in close proximity to each other as well as be individually addressable by external electrodes via tunable electron tunneling or capacitive coupling1. Several approaches have been proposed for the physical realization of qubits, including single photons2, trapped ions3, superconducting circuits4, single defects or atoms in diamond5 and in silicon matrices6, as well as semiconductor quantum dots (QDs)7,8,9,10. While encouraging achievements have been made using superconducting qubits operating at extremely low temperatures, recently, semiconductor QD qubits have emerged as the subject of intensive research not only for their great promise for high-temperature operation, but also for cost-effective fabrication using currently-existing semiconductor technology11,12,13.

Among the possible materials choices for semiconductor qubits, Si-based QDs are particularly attractive because complementary metal-oxide-semiconductor (CMOS) technology crucially enables the integration of Si-based QDs with Si CMOS electronics for qubit control, read-out and subsequent signal processing. To date, the operation of Si qubits has been validated only for very low temperature (<2 K) operation13. This is because that using current lithographic patterning technology, it is extremely difficult to produce sufficiently small-sized Si QDs (i.e. <5 nm; the excitonic Bohr radius is 4.9 nm for Si) that can be placed in close proximity to each other. Ge-based QDs are an exciting alternative for high-temperature qubit operation because of their larger exciton Bohr radius (~24.9 nm for Ge). Thus, Ge QDs have stronger quantum confinement as compared to Si QDs at comparable sizes. Another important benefit is that Ge QDs have stronger spin-orbital coupling than the corresponding Si QDs14, which is critical for electrically-driven spin qubits and spintronics applications. Therefore, it is important to establish reliable nano-fabrication schemes for generating size-tunable Ge QDs with controllable nearest-neighbor coupling.

In this paper, we report the experimental fabrication of a pair of double QD (DQD) system comprising of two spherical-shaped Ge QDs embedded within SiO2/Si3N4 matrices with tunable QD sizes and controllable QD spacings using a combination of CMOS fabrication technology and novel self-assembly growth techniques. This DQD system is formed by the thermal oxidation of nano-patterned poly-Si0.85Ge0.15 islands at the sidewalls of lithographically-patterned ridges of Si3N4/poly-Si. The diameter of individual Ge QDs is essentially determined by the geometrical conditions (thickness, width, and length) of the nano-patterned poly-Si0.85Ge0.15 spacer islands prior to thermal oxidation, whereas the interspace between the paired QDs is tunable by adjusting the width of the lithographically-patterned ridge in combination with the thermal oxidation time. Using our experimental approach, we have achieved high symmetry for our Ge DQDs in terms of both the geometrical sizes and shapes of Ge QDs as well as for the coupling barriers between the QDs and their external electrodes.

Results

Symmetrical double Ge quantum dots embedded within host matrices of SiO2/Si3N4

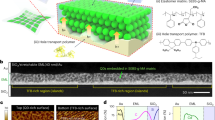

Using the experimental fabrication procedure (Fig. 1) described in Method Section, we were able to fabricate a pair of Ge QDs simultaneously at each sidewall corner of nano-patterned Si3N4/Si ridges on top of the Si substrate, as shown by the scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) and energy dispersive x-ray spectroscopy (EDX) map micrographs in Fig. 2.

Detailed process flow diagrams showing the fabrication of double QDs embedded within SiO2/Si3N4 matrices via the thermal oxidation of nano-patterned SiGe spacer layers encapsulating Si3N4 layers that are deposited over ridges of poly-Si. (a) Lithographically-patterned, 20–75 nm-wide poly-Si ridges are formed over buffer layers of SiO2 on top of Si substrate. (b) Next, sequential deposition of 25 nm-thick Si3N4 and 30 nm-thick poly-Si0.85Ge0.15 layers conformally encapsulating the poly-Si ridges. Inset is the corresponding cross-sectional SEM micrograph. (c) Symmetrical spacer stripes of poly-Si0.85Ge0.15 are subsequently fabricated at each sidewall of the Si3N4/poly-Si ridges by a direct etch back process using SF6/C4F8 plasma. The widths and heights of the poly-Si0.85Ge0.15 spacer stripes are directly determined by the process times for deposition and etch back of poly-Si0.85Ge0.15 spacer layers. (d) Lithographically-patterning processes across the spacer stripes of poly-Si0.85Ge0.15 are conducted to define the lengths of the poly-SiGe spacer islands. Inset is the corresponding top-view SEM micrograph. (e) Symmetrical poly-Si0.85Ge0.15 spacer islands with widths (W)/heights (H)/lengths (L) of 20–30 nm/25–35 nm/30–40 nm are formed. Inset is the corresponding plan-view SEM micrograph. (f) Next, a pair of spherical Ge QDs is formed at each sidewall corner of the nano-patterned Si3N4/poly-Si ridge by thermal oxidation at 900 °C. (g) Finally, after a direct etch-back process in order to expose the Si surrounding the DQDs, self-aligned silicide (Salicide) external electrodes are fabricated by the deposition of either Ni or Ti, thermal annealing, and selective etching.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) observations following thermal oxidation of poly-SiGe spacer islands nano-patterned over Si3N4 layers deposited over poly-Si ridges. (a) STEM micrograph, (b) EDX maps of elemental Ge, N, Si, and O of the paired Ge QDs, each with diameter of 12 nm, formed at each sidewall of the poly-Si ridges.

Tunability of Ge quantum dot size

Most importantly, we successfully demonstrated precise control of the Ge QD diameter by controlling the process times for deposition and etch back for poly-SiGe spacer layers in combination with the exposure dose of electron-beam lithography for poly-SiGe spacer islands, thereby determining their width (W), height (H), and length (L), respectively. Thanks to the good conformity of low-pressure chemical vapor deposition (LPCVD) poly-SiGe spacer layers encapsulating the Si3N4/poly-Si nano-ridges as shown in the inset SEM micrograph of Fig. 1(b), the thickness of poly-SiGe spacer layers (i.e., the width of the poly-SiGe spacer islands) is essentially determined by their deposition time. The height of the poly-SiGe spacer islands is easily tailored by controlling the process times for poly-SiGe etch back, whereas the exposure dose of the second electron-beam lithography step essentially defines the lengths of the poly-SiGe spacer islands. We have conducted extensive experimental works in terms of the process times of etch back as well as electron-beam lithographic patterning for the production of size-tunable SiGe spacer islands. For a given deposition thickness of 30 nm for the SiGe spacer layers encapsulating the 25 nm-thick Si3N4/40 nm-thick poly-Si ridges, we have varied the width and height (W/H) of the SiGe spacer layers from 30 nm/35 nm to 25 nm/20 nm. This was achieved by increasing the process time of etch-back (using SF6/C4F8 plasma) from 7 to 10 seconds as shown in the cross-sectional SEM micrographs of Fig. 3(a–c). For varying the length of the SiGe spacer islands, which is essentially defined by the 2nd electron-beam lithographic patterning step across the poly-Si nanoridges, we have additionally attempted 40 nm–30 nm lengths by increasing the exposure dose of electrons from 4.8 × 10−16 C to 6.0 × 10−16 C (i.e., by increasing the beam exposure time from 4.8 μs to 6.0 μs for a given electron-beam current of 100 pA). These results are shown in the plan-view SEM micrographs of Fig. 3(d–f). It is clearly seen from the plan-view SEM micrographs in Fig. 3(g,h) and in the cross-sectional TEM micrographs in Fig. 3(j–l), respectively, that pairs of spherical Ge DQDs with diameter of 12 nm, 16 nm, and 20 nm appear at each sidewall corner of the Si3N4/Si ridges following thermal oxidation (at 900 °C for 10.5 min) of poly-Si0.85Ge0.15 islands with widths/heights/lengths of 25 nm/20 nm/30 nm, 30 nm/25 nm/35 nm, and 30 nm/35 nm/40 nm, respectively.

A pair of Ge DQDs simultaneously fabricated by the thermal oxidation of poly-SiGe spacer islands nanopatterned over Si3N4 layers encapsulating poly-Si ridges. 12 nm–20 nm Ge DQDs are produced by controlling the width (25–30 nm), height (20–35 nm), and length (30–40 nm) of the poly-SiGe spacer islands by varying the process times for poly-SiGe deposition and etch back in combination with the exposure dose of electron-beam lithography. Cross-sectional SEM micrographs of poly-SiGe spacer layers with Widths/Heights (W/H) of (a) 30 nm/35 nm, (b) 30 nm/25 nm, and (c) 25 nm/20 nm produced by using SF6/C4F8 plasma etch-back with process times of 7 sec, 9 sec, and 10 sec, respectively. Plan-view SEM micrographs of e-beam lithographically-patterned poly-SiGe spacer islands with lengths of (d) 40 nm, (e) 35 nm, and (f) 30 nm produced by exposure electron doses of 4.8 × 10−16 C, 5.4 × 10−16 C and 6.0 × 10−16 C, respectively. Following thermal oxidation at 900 °C for 10.5 min, plan-view SEM/cross-sectional TEM micrographs of (g,j) 20 nm, (h,k) 16 nm and (i,l) 12 nm diameter Ge QDs are produced by controlling the widths (25–30 nm), heights (25–35 nm), and lengths (30–40 nm) of the poly-SiGe spacer islands by varying the process times of poly-SiGe etch back and E-beam exposure. Inset on the left shows the corresponding structure schematic diagrams for clarity.

Controllability of inter-dot spacing

Based on our described fabrication approaches, several pairs of Ge DQDs were successfully, simultaneously produced at each sidewall corner of nano-patterned Si3N4/Si ridges. Figure 4 shows that following thermal oxidation at 900 °C for 10.5 min, the inter-dot spacing between double Ge QDs that are 12 nm in diameter was varied from 110 nm, 85 nm to 60 nm by decreasing the width of the lithographically-patterned poly-Si ridges from 75 nm, 50 nm to 25 nm, respectively. Further evidence for the tunablity of inter-dot spacing achieved by controlling the width of the nano-patterned Si3N4/poly-Si ridges is also shown for larger, 20 nm diameter Ge DQDs in Fig. 5.

Another important finding of note from Figs 2–5 regards the penetration of Ge QDs into the Si3N4 layer. Our previous papers have already reported that the depth of penetration of Ge QDs into Si3N4 is enhanced by increasing the thermal oxidation time15,16,17. In this work, we also observed that by increasing the thermal oxidation time from 10.5 min, through 27 min to 40 min, the separation between the double QDs is reduced by approximately 40 nm due to the significantly enhanced penetration of Ge QDs within Si3N4. These results are shown in Fig. 6 for the cases of the 30 nm-wide and 60 nm-wide poly-Si ridges. As shown in Fig. 6(a,d), 10.5 min of thermal oxidation at 900 °C produces a pair of Ge QDs that are located at each sidewall corner of the nano-patterned Si3N4/Si ridges. It is important to note that by increasing the duration of thermal oxidation at 900 °C to 27 min, the Ge DQDs have burrowed into the Si3N4 spacer layers for a depth of penetration of ~12 nm as shown in Fig. 6(b,e). Our experimental findings suggest that the spacing between the two Ge QDs is determined not only by the width of the nano-patterned Si3N4/poly-Si ridges, but also by the depth of penetration of the Ge QD into Si3N4 (dependent on the process time for thermal oxidation).

TEM micrographs of Ge DQDs formed at the sidewall corners of 30 nm-wide poly-Si ridges by thermal oxidation at 900 °C for (a) 10.5 min, (b) 27 min, and (c) 40 min. The depth of penetration of Ge QDs within the Si3N4 spacer layers is enhanced by increasing thermal oxidation time, leading to the reduction in the inter-dot spacing between the DQDs. The reduction in the inter-dot spacing with increasing thermal oxidation time is also evidenced for Ge DQDs in the cases of 60 nm-wide poly-Si nanoridges as shown for (d) 10.5 min and (e)27 min oxidation time. A longer oxidation process not only increases the penetration of Ge QDs through the Si3N4 layers, making the pair of QDs closer to each other, but also improves the crystallinity of the Ge QDs as shown in the HRTEM observations for (f) 10.5 min and (g) 27 min thermal oxidation at 900 °C.

Discussion

Detailed mechanisms for (1) the formation of spherical Ge QDs by thermal oxidation of poly-SiGe islands in close proximity to Si3N4 layers and (2) the penetration of Ge QDs through Si3N4 layers involve an exquisite, symbiotic interplay between Ge, Si, and O interstitials, have been described in detail in our previous publications15,16,17,18,19,20. In brief, the formation of Ge QDs by the thermal oxidation of the poly-SiGe islands located at the sidewall corners of the Si3N4/poly-Si ridges involves the preferential oxidation of Si and the Ge enrichment of the as-yet-unoxidized poly-SiGe regions. Ultimately, Ge crystallite clusters are formed by the progressive concentration of the Ge content within the remaining (unoxidized) poly-SiGe grains until the Si content is completely oxidized. With further oxidation, the Ge crystallite clusters can be made to penetrate the Si3N4 layers in close proximity due to Ge catalytically-enhancing the local decomposition and oxidation of Si3N415,16,17. The migration of Ge QDs within Si3N4 involves a novel SiO2 formation-destruction mechanism16,17,18,19,20. Concurrent with the migration, the Ge crystallites grow in size by Ostwald Ripening culminating in complete coalescence, and resulting in a single, spherical Ge QD being formed at each sidewall corner of the Si3N4/poly-Si ridge.

The first important feature of our paired DQDs is the high symmetry observed both in Ge QD size and shapes, which is dependent on the dimensions of the nano-patterned poly-SiGe spacer islands at each sidewall corner of the Si3N4/poly-Si ridges. This is because the Ge content coalescing to form each spherical Ge QD during the selective oxidation of the poly-SiGe islands is exactly the same. The diameter of each spherical Ge QD is essentially determined by the geometrical sizes (width/height/length) of the poly-SiGe spacer islands. The width and height of the poly-SiGe spacer islands are tailored by controlling the process times of deposition and etch back for poly-SiGe spacer layers, whereas the second e-beam lithography step essentially defines the length of the poly-SiGe spacer islands.

The second important feature is the control of the spacing between the DQDs. The spacing between DQDs is primarily determined by the width of the nano-patterned ridge, and is also further reduced by the penetration of the Ge QDs within the Si3N4 overlayer. The exquisite control of the inter-Ge QD spacing lies in not only the conformal deposition of poly-SiGe spacer layers encapsulating the Si3N4/Si nanoridges, but also the controllable migration of the Ge QDs towards local sources of Si interstitials (emitted by either the Si3N4 or poly-Si layers)16,17,18. Increasing the process time of thermal oxidation not only facilitates Ge QD migration within the Si3N4 layer thus reducing the spacing between DQDs, but it also improves the crystallinity of the Ge QDs as shown in Fig. 4(e,f). The conformal spacer layers of Si3N4 over the poly-Si ridges are deliberately designed to be the initial, local source of Si interstitials to direct the Ge QD migration towards, reducing the inter-QD spacing.

The third important feature is that the resulting oxide layers, formed by the thermal oxidation of the poly-SiGe spacer islands, encapsulate the Ge QDs and serve as inherent tunneling barriers between the Ge QDs and external silicide electrodes in a self-organized manner. Once again, thanks to the processes of conformal spacer deposition, direct etch-back and thermal oxidation, symmetrical tunneling barriers between the DQDs and external electrodes could be simultaneously generated by our proposed fabrication processes. That is, following direct etch-back of the top oxide layers in order to expose the Si surface surrounding the DQDs and nanopatterned ridges (Fig. 1(f)), external electrodes could be subsequently formed by self-aligned refractory metal silicidation (also called salicidation) process (Fig. 1(g)).

Based on our proposed approach, the tunability of the QD diameter and inter-dot spacing is achieved by a highly-controllable combination of nano-spacer fabrication, lithographic-patterning, and thermal oxidation of SiGe spacer islands. This combination, which includes the deposition and etch back of poly-SiGe spacer layers, lithographic patterning of SiGe spacer islands and Si ridges, and the thermal oxidation of SiGe spacer islands, employs standard fabrication processes in existing CMOS technology and therefore, by definition, is suitable for large-scale manufacturing. The uniformity of the resulting, fabricated Ge DQDs has been examined extensively using TEM/SEM observations. For further clarity, three TEM micrographs (Fig. 7) were included for each structure in order to demonstrate the high degree of symmetry, uniformity and reproducibility of our fabricated Ge DQDs under different combinations of process conditions.

Using our controllable spacer and selective oxidation of poly-SiGe approach, a pair of symmetrical Ge DQDs with diameters as small as 12 nm and inter-dot spacing as close as 13 nm have been achieved (Fig. 8). Maurand et al. have reported the first Si-QD spin qubits implemented on a foundry-compatible Si CMOS platform using a 28 nm technology node with 64 nm pitch11. These reported Si-QD qubit devices, consisting of a two-gate pMOSFET (channel length of ~30 nm and inter-gate spacing of ~35 nm) within which, one gate defines a 30 nm-QD encoding a hole spin qubit and the other gate defines another 30 nm-QD for the qubit read-out. The authors demonstrated hole spin-qubit functionality with high fidelity at T = 10 mK. Our previous reports on the experimental fabrication of Ge-QD (with diameter of ~11 nm) single-hole transistors (SHTs) have already demonstrated clear Coulomb-blockade oscillatory current with peak-to-valley ratios (PVCR) > 100 and superior Coulomb stability at temperature as high as T = 77–140 K21,22. From the Coulomb-stability diagram, the extracted single-hole addition energy of 10–13 meV is a testament to the well-separated, discrete energy levels due to the strong quantum confinement effects for our 11 nm Ge QDs. By further downscaling the Ge QD sizes to 6 nm, we have demonstrated room-temperature operation of Ge-QD SHTs exhibiting clear Coulomb-blockade oscillatory current spectra with PVCR as high as 75023. Based on our previous accomplishments on Ge-QD SHTs, we believe that the operating temperature of qubits based on our Ge DQDs could be significantly increased to >100 K or even room temperature.

Conclusions

We experimentally demonstrated the feasibility of paired, spherical-shaped Ge DQDs embedded within SiO2/Si3N4 matrices with tunable QD sizes and controllable inter-QD spacings using a CMOS nano-spacer fabrication technique in combination with selective oxidation of SiGe. The diameter of individual Ge QDs is essentially determined by the geometry (thickness, length, and width) of the poly-Si0.85Ge0.15 spacer islands prior to thermal oxidation. These dimensions are easily controlled by adjusting the process times of poly-SiGe layers deposition and their etch back. The inter-QD spacing is tunable by controlling both the width of the lithographically-patterned ridge as well as the thermal oxidation time. Using our experimental approach, we have achieved high symmetry for our Ge DQDs in terms of both the geometrical sizes and shapes of Ge QDs as well as the coupling barriers between the QDs and external electrodes. We envisage further scientific exploration of our Ge DQDs toward the ultimate goal of demonstrating advanced Ge-based QD qubit devices for practical applications.

Methods

Formation of self-organized, double Ge spherical quantum dots

The fabrication of paired Ge DQDs embedded within host matrices of SiO2/Si3N4 was initiated with the sequential deposition of bi-layers of 10 nm-thick SiO2 and 40 nm-thick poly-Si over Si substrates using low-pressure chemical vapor deposition (LPCVD). Poly-Si ridges of 25–75 nm in width were subsequently fabricated using a combination of electron-beam lithography and SF6/C4F8 plasma etching (Fig. 1(a)). Next, bi-layers of 25 nm-thick Si3N4 and 30 nm-thick poly-Si0.85Ge0.15 were sequentially deposited using LPCVD (Fig. 1(b)) in order to have conformal encapsulation over the poly-Si ridges. Following a direct etch-back process using SF6/C4F8 plasma (Fig. 1(c)), symmetrical spacer stripes of poly-Si0.85Ge0.15 with width/height (W/H) of 25–30 nm/20–35 nm were symmetrically produced by tuning the etch-back time at each sidewall of the Si3N4/poly-Si ridges. A second electron-beam lithography step in combination with SF6/C4F8 plasma etching was conducted across the poly-Si0.85Ge0.15 spacer stripes in order to define the length of 30–40 nm for poly-Si0.85Ge0.15 islands at each sidewall of the nano-patterned ridges (Fig. 1(d)). Finally, thermal oxidation at 900 °C for 10–27 min in an H2O ambient was performed to convert these poly-Si0.85Ge0.15 spacer islands to two spherical Ge QDs (Fig. 1(e)) at each sidewall corner of the ridges.

Structural/chemical composition characterization

Structural properties and chemical composition of Ge DQDs embedded with SiO2/Si3N4 were assessed using cross-sectional high-resolution scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) and energy dispersive x-ray spectroscopy (EDX). The thickness of the TEM/EDX specimens were thinned to 60 nm by low-energy ion milling using focus ion beam (FIB). The Osiris & Talos TEM system operates at 200 kV and is equipped with a high-angle annular dark field (HAADF) detector. For EDX mapping, the camera length was 122 mm, and it took 20 min. to complete one mapping image.

References

Dennis, E., Kitaev, A., Landahl, A. & Preskill, J. Topological quantum memory. J. Math. Phys. 43, 4452–4505, https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1499754 (2002).

Mi, X. et al. A coherent spin-photon interface in silicon. Nature 555, 599–606, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature25769 (2018).

Mehta, K. K. et al. Integrated optical addressing of an ion qubit. Nature Nanotechnology 11, 1066–1070, https://doi.org/10.1038/nnano.2016.139 (2016).

Devoret, M. H. & Schoelkopf, R. J. Superconducting circuits for quantum information: an outlook. Science 339, 1169–1174, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1231930 (2013).

London, P. et al. Detecting and polarizing nuclear spins with double resonance on a single electron spin. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 067601-1–067601-5, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.111.067601 (2013).

Tosi, G. et al. Silicon quantum processor with robust long-distance qubit couplings. Nature Communications 8, 450-1–450-11, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-017-00378-x (2017).

Veldhorst, M. et al. An addressable quantum dot qubit with fault-tolerant control-fidelity. Nature Nanotechnology 9, 981–985, https://doi.org/10.1038/nnano.2014.216 (2014).

Yoneda, J. et al. A quantum-dot spin qubit with coherence limited by charge noise and fidelity higher than 99.9. Nature Nanotechnology 13, 102–106, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41565-017-0014-x (2018).

Watson, T. F. et al. A programmable two-qubit quantum processor in silicon. Nature 555, 633–637, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature25766 (2018).

Samkharadze, N. et al. Strong spin-photon coupling in silicon. Science 359, 1123–1127, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aar4054 (2018).

Maurand, R. et al. A CMOS silicon spin qubit. Nature Communications 7, 13575-1–13575-6, https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms13575 (2016).

Lo, C. C. & Morton, J. Silicon’s second act: Can this semiconductor workhorse take computing into the quantum era?, IEEE Spectrum, 37–43 (2014).

Pillarisetty, R. et al. Qubit device integration using advanced semiconductor manufacturing process technology, in IEDM Tech. Digest, 133–136 (2018)

Zhou, Y. et al. Electrical spin injection and transport in germanium. Phys. Rev. B 84, 125323-1–125323-7, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.84.125323 (2011).

Chien, C. Y. et al. Nanoscale, catalytically enhanced local oxidation of silicon-containing layers by ‘burrowing’ Ge quantum dots. Nanotechnology 22, 435602-1–435602-6, https://doi.org/10.1088/0957-4484/22/43/435602 (2011).

Chen, K. H., Wang, C. C., George, T. & Li, P. W. The role of Si interstitials in the migration and growth of Ge nanocrystallites under thermal annealing in an oxidizing ambient. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 9, 339-1–339-5, https://doi.org/10.1186/1556-276X-9-339 (2014).

George, T., Li, P. W., Chen, K. H., Peng, K. P. & Lai, W. T. Symbiotic semiconductors: unusual and counter-intuitive Ge/Si/O interactions. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 50, 105101-1–105101-12, https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-6463/aa59ab (2017).

Liao, P. H. et al. Self-organized gate stack of Ge nanosphere/SiO2/Si1-xGex enables Ge-based monolithically-integrated electronics and photonics on Si platform. In VLSI Tech. Dig. Jun. 2018, pp. 157–158 (2018).

Chen, K. H., Wang, C. C., George, T. & Li, P. W. The pivotal role of SiO formation in the migration and Ostwald ripening of Ge quantum dots. Appl. Phys. Lett. 105, 122102-1–122102-5, https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4896504 (2014).

Chen, K. H., Wang, C. C., Lai, W. T., George, T. & Li, P. W. The pivotal role of oxygen interstitials in the dynamics of growth and movement of germanium nanocrystallites. Cryst Eng Comm. 17, 6370–6375, https://doi.org/10.1039/C5CE00991J (2015).

Chen, I. H., Chen, K. H., Lai, W. T. & Li, P. W. Single germanium quantum-dot placement along with self-aligned electrodes for effective management of single charge tunneling. IEEE Trans. Electron. Dev. 59, 3224–3230, https://doi.org/10.1109/TED.2012.2217973 (2012).

Chen, I. H., Lai, W. T. & Li, P. W. Realization of solid-state nanothermometer using Ge quantum-dot single-hole transistor in few-hole regime. Appl. Phys. Lett. 104, 243506-1–243506-5, https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4884296 (2014).

Chen, G. L., Kuo, D. M. T., Lai, W. T. & Li, P. W. Tunneling spectroscopy of a germanium quantum dot in single-hole transistors with self-aligned electrodes. Nanotechnology 18, 475402-1–475402-4, https://doi.org/10.1088/0957-4484/18/47/475402 (2007).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology of Republic of China (MOST 105-2221-E-009-134-MY3 and 108-2633-E-009-001).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.T.L. and C.C.L. conducted DQD structure fabrication. P.K.P. characterized the TEM/STEM/EDX experimentation. L.H.C. contributed to data analysis. T.G. carried out material characterization and revised the manuscript. L.P.W. conceived the study, supervised the work, contributed to data analysis and the manuscript preparation. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Huang, TL., Peng, KP., Chen, CL. et al. Tunable diameter and spacing of double Ge quantum dots using highly-controllable spacers and selective oxidation of SiGe. Sci Rep 9, 11303 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-47806-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-47806-0

This article is cited by

-

Study on crystal growth of Ge/Si quantum dots at different Ge deposition by using magnetron sputtering technique

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

The amazing world of self-organized Ge quantum dots for Si photonics on SiN platforms

Applied Physics A (2023)

-

SiGe nanocrystals in SiO2 with high photosensitivity from visible to short-wave infrared

Scientific Reports (2020)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.