Abstract

The long-chain (≥C20) polyunsaturated fatty acid biosynthesis capacity of fish varies among species, with trophic level hypothesised as a major factor. The biosynthesis capacity is largely dependent upon the presence of functionally diversified fatty acyl desaturase 2 (Fads2) enzymes, since many teleosts have lost the gene encoding a Δ5 desaturase (Fads1). The present study aimed to characterise Fads2 from four teleosts occupying different trophic levels, namely Sarpa salpa, Chelon labrosus, Pegusa lascaris and Atherina presbyter, which were selected based on available data on functions of Fads2 from closely related species. Therefore, we had insight into the variability of Fads2 within the same phylogenetic group. Our results showed that Fads2 from S. salpa and C. labrosus were both Δ6 desaturases with further Δ8 activity while P. lascaris and A. presbyter Fads2 showed Δ4 activity. Fads2 activities of herbivorous S. salpa are consistent with those reported for carnivorous Sparidae species. The results suggested that trophic level might not directly drive diversification of teleost Fads2 as initially hypothesised, and other factors such as the species’ phylogeny appeared to be more influential. In agreement, Fads2 activities from P. lascaris and A. presbyter were similar to their corresponding phylogenetic counterparts Solea senegalensis and Chirostoma estor.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The crucial roles of long-chain (≥C20) polyunsaturated fatty acids (LC-PUFA) such as eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA, 20:5n-3), docosahexaenoic acid (DHA, 22:6n-3) and arachidonic acid (ARA, 20:4n-6) in human nutrition and their potential health benefits have been extensively studied1,2,3,4. These lipid components are implicated in a range of structural, functional and signaling processes1,4,5. LC-PUFA, particularly those of the n-3 series, are naturally produced by lower trophic organisms of the marine food web including single-celled organisms6,7 and invertebrates8, and are accumulated in higher trophic organisms. Consequently, fish are the main sources of these beneficial LC-PUFA in the human food basket9,10. However, current growth of the human population, which will probably exceed 9 billion by 2050, along with overexploitation of traditional fisheries, make aquaculture activities a keystone in order to meet future dietary demand for LC-PUFA11. While farmed fish products have been good sources of LC-PUFA for human consumers when high fishmeal and fish oil levels have been included in aquafeed formulations, increasing levels of inclusion of non-marine ingredients in current aquafeed formulations can potentially lead to growth and health issues in species with low capacity to use alternative plant-based ingredients and greatly reduces the contents of healthy LC-PUFA for consumers12.

One approach to address this problem is bioengineering of terrestrial plants to produce LC-PUFA and, therefore, help maintain their level in aquafeeds and in turn conserve the quality of farmed fish flesh13,14. An alternative to bioengineering could be the use of marine macro and microalgae, although there are some drawbacks such as limited production and high cost, as well as the potential presence of anti-nutritional factors12,15. Alternatively, the culture of fish species with high capability to biosynthesise LC-PUFA from shorter chain (C18) polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) (e.g. 18:3n-3 and 18:2n-6) abundant in terrestrial vegetable oils could also be a sensible approach to support the sustainable expansion of aquaculture. However, with a few exceptions like salmonids, most species currently farmed in North America and Europe are marine carnivores with no, or very limited, capacity for the endogenous production (biosynthesis) of LC-PUFA from their C18 PUFA precursors15,16. The trophic level of fish species, along with their habitat (freshwater vs. marine) and trophic ecology, have all been suggested to influence the capacity for biosynthesis of LC-PUFA of fish16,17 and, consequently, the way essential fatty acid (FA) requirements are satisfied by the diet. In species with high capacity to convert C18 PUFA to LC-PUFA, essential FA can be satisfied by including vegetable oils containing C18 PUFA in the diet. In contrast, species with low capacity to convert C18 PUFA to LC-PUFA require a dietary supply of the latter to satisfy their essential FA demands, with this typically achieved by including fish oil16,18,19,20,21.

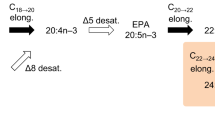

The biosynthesis of LC-PUFA from C18 PUFA precursors is carried out in vertebrates by aerobic desaturase and elongase enzymes16 (Fig. 1). Fatty acyl desaturases (Fads or Δx) introduce double bonds between a pre-existing double bond and the carboxylic group and are therefore termed “front-end” desaturases. Moreover, elongation of very long chain fatty acids (Elovl) proteins are responsible for the initial condensation reaction of the elongation pathway that results in the addition of two carbons to pre-existing FA substrate16. In mammals, two Fads, namely FADS1 and FADS2, are the main desaturase enzymes involved in LC-PUFA biosynthesis16. Basically, mammalian FADS1 possesses Δ5 desaturase activity responsible for the synthesis of EPA and ARA from 20:4n-3 and 20:3n-6, respectively. FADS2, while mostly possesses Δ6 desaturase activity that catalyzes the desaturation of C18 PUFA, namely 18:3n-3 and 18:2n-6 (Fig. 1), it has been also shown to catalyse Δ4 desaturation to yield DHA acid and 22:5n-6 acid in human cells22. Importantly, FADS2 also has an important role in mammals in the synthesis of DHA from EPA via the so-called “Sprecher pathway”, which comprises two sequential elongations from EPA to 24:5n-3, a Δ6 desaturation leading to 24:6n-3 and a final chain-shortening (partial β-oxidation) to produce DHA23.

In contrast to mammals, virtually all Fads isolated from Teleostei species are phylogenetically identified as fads2 orthologues suggesting that they have lost the fads1 gene during evolution24, with the sole exception of basal teleosts like the Japanese eel Anguilla japonica, which retained a fads1 encoding a ∆5 desaturase25. Many teleost Fads2 show Δ6 desaturase activity along with Δ8 desaturase activity similar to mammalian FADS226,27. However, in contrast to mammalian FADS2, a greater functional diversification has been described among teleost Fads2, thus enabling some species to compensate for loss of fads1 and thus enhance their LC-PUFA biosynthetic capacities. Bifunctional Δ6Δ5 desaturases have been reported in zebrafish Danio rerio28, rabbitfish Siganus canaliculatus29, pike silverside Chirostoma estor18, Nile tilapia Oreochromis niloticus30, striped snakehead Channa striata10, African catfish Clarias gariepinus31, silver barb Barbonymus gonionotus32 and tambaqui Collossoma macropomum33. Moreover, Δ4 Fads2, with some activity as Δ5 desaturases, have been reported in rabbitfish29, Senegalese sole Solea senegalensis21, C. estor18, C. striata34, O. niloticus and Japanese medaka Oryzias latipes35. Finally, salmonids such as Atlantic salmon Salmo salar36 and rainbow trout Oncorhynchus mykiss37 possess Fads2 categorised as monofunctional Δ5 desaturases, although that of salmon was recently reported to also exhibit Δ6 activity35.

The precise repertoire and function of teleost Fads2 is species-specific and speculated to be influenced by, or a consequence of, one or more factors including trophic level, habitat (freshwater vs. marine) and trophic ecology18,21,29. Among them, the position of the species in the food chain (trophic) was postulated as a major factor influencing LC-PUFA biosynthetic capability in fish16 when S. canaliculatus, a marine herbivore, was found to possess all enzymatic activities required for LC-PUFA biosynthesis29,38, an ability previously believed to be restricted to freshwater and salmonid species. To further corroborate whether this hypothesis can be extended to other teleosts, the present study aimed to isolate and molecularly characterise putative fads2 from four marine teleosts, namely Sarpa salpa, Chelon labrosus, Pegusa lascaris and Atherina presbyter, occupying different trophic levels. Where possible, we selected these species because functional data of Fads2 from members of their corresponding phylogenetic groups had been published previously, allowing us clarify whether other factors might also account for functional diversification of teleost Fads2.

Results

Sequence and phylogenetic analysis

The putative fads2 from S. salpa, C. labrosus, P. lascaris and A. presbyter all exhibited ORF sequences of 1338 bp encoding putative proteins of 445 amino acids (aa), which were deposited in the GenBank database under the accession numbers MH293506, MH293504, MH293505 and MH293503, respectively. The deduced aa sequences from all species contained typical conserved features of front-end desaturases (Fig. 2), namely a heme binding motif HPGG and three histidine boxes (HXXXH, HXXHH, QXXHH). The four aa regions determining regioselectivity of Fads2 enzymes39 varied among the studied species. The A. presbyter and P. lascaris Fads2 possessed YXXN aa residues (282–285aa, Fig. 2), while C. labrosus and S. salpa Fads2 possessed FXXQ (282–285aa, Fig. 2).

Alignment of the deduced amino acid (aa) sequences of the novel fatty acyl desaturases of Sarpa salpa, Chelon labrosus, Pegusa lascaris and Atherina presbyter. Identical residues are shaded black, heme binding motif is indicated by asterisks, histidine boxes are dashed black framed, and regions determining regioselectivity is solid black framed.

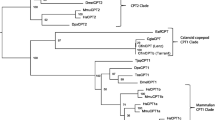

The phylogenetic analysis revealed that all putative Fads2 were clustered together with Fads2 from other Teleostei species (bootstrap = 97%), and clearly separated from a branch containing Fads1 sequences (Fig. 3). The A. presbyter Fads2 was clustered with Atherinomorphae species including Δ4 Fads2 from O. latipes (XP_011474361) and C. estor (AHX39206), and Δ6Δ5 Fads2 from C. estor (AHX39207) (bootstrap = 78%) (Fig. 3). The S. salpa Fads2 grouped with Δ6 Fads2 from other Sparidae species, namely Sparus aurata (ADD50000) and Acanthopagrus schlegelii (ANJ04910) (bootstrap = 100%) (Fig. 3). The P. lascaris Fads2 and S. senegalensis Δ4 Fads2 (AEQ. 92868) were clustered together (bootstrap = 100%) but this clade was separated from other Pleuronectiformes Δ6 Fads2 such as those of Scophthalmus maximus (AAS49163) and Paralichthys olivaceus (AJG36440) (Fig. 3).

Phylogenetic tree including the deduced amino acid (aa) sequences of the fatty acyl desaturases of Sarpa salpa, Chelon labrosus, Pegusa lascaris and Atherina presbyter. The horizontal branch length is proportional to the aa substitution rate per site. Demonstrated desaturase activities are included in all Fads-like sequences as “Δx”. The asterisk (“*”) in some Δ6 desaturases denotes in demonstrated ability of these enzymes to operate towards both C18 (e.g. 18:3n-3) and C24 (e.g. 24:5n-3) substrates35.

Functional characterisation of Fads2 desaturases

Our results show that Fads2 from S. salpa and C. labrosus showed Δ6 desaturase activity towards 18:2n-6 and 18:3n-3 since they were able to produce 18:3n-6 and 18:4n-3, respectively, when expressed in yeast (Table 1). Moreover, both S. salpa and C. labrosus Fads2 also exhibited Δ8 activity towards, with 20:2n-6 and 20:3n-3 being desaturated to 20:3n-6 and 20:4n-3, respectively (Table 1). No Δ5 or Δ4 desaturations were detected in yeast expressing the S. salpa and C. labrosus fads2 desaturases (Table 1). Moreover, transgenic yeast expressing A. presbyter and P. lascaris fads2 showed Δ4 desaturase activity towards 22:4n-6 and 22:5n-3 since they could be desaturated to 22:5n-6 and 22:6n-3, respectively (Table 1). Neither Δ6, Δ8 nor Δ5 desaturase activities were detected in yeast expressing fads2 from A. presbyter and P. lascaris (Table 1).

Tissue expression of fads2

Tissue expression of fads2 in brain, gill, intestine, heart, liver and muscle of the studied species is shown in Fig. 4. Expression of fads2 was found in all tissues analysed. S. salpa and P. lascaris showed the highest fads2 expression levels in liver, brain and intestine (Fig. 4). A similar pattern was observed in C. labrosus and A. prebyter, although the highest expression in brain could not be confirmed statistically (Fig. 4). Heart showed the lowest levels of fads2 expression among all tissues considered in the analysis (Fig. 4).

Distribution of fads2 mRNA levels in tissues of Sarpa salpa, Chelon labrosus, Pegusa lascaris and Atherina presbyter. Data are shown as geometric mean log normalised expression ratios ± standard errors (n = 4, except for heart and muscle of S. salpa where n = 3, brain of C. labrosus where n = 3, and brain and heart of A. presbyter where n = 2 and n = 1, respectively). Different letters denote significant differences among tissue within each species (P < 0.05, One-way ANOVA, Tukey HSD test).

Discussion

Fish vary in their LC-PUFA biosynthetic capacity that, in turn, determines the essential FA requirements in each species. The species’ trophic level, i.e. the position of an organism in the food chain, was proposed as a major factor influencing LC-PUFA biosynthetic capability in fish16 after S. canaliculatus, a marine herbivore, was found to possess all enzymatic activities required to biosynthesise LC-PUFA from C18 PUFA precursors, believed previously to be limited to freshwater and salmonid species29,38. To clarify whether this assumption could be extended beyond S. canaliculatus, four marine fish species occupying different trophic levels were selected and their Fads2, a key enzyme in LC-PUFA biosynthesis in teleosts, were characterised16. The results of the present study, summarised in Table 2, suggested that the trophic level of a given species cannot alone account for functionalisation of Fads2 occurring in that particular species and thus enabling a more efficient LC-PUFA biosynthesis.

Acquision of new or additional functions (neo and subfunctionalisation) within Fads2 is an advantageous feature in animals such as teleosts that have lost Fads1 with Δ5 activity. Possessing such a trait, however, cannot be linked directly to trophic level of the species, but rather appears to be more dependent upon the position that particular species occupies within the teleost clade. Like S. canaliculatus, the herein studied S. salpa is a truly herbivorous fish species thriving on low LC-PUFA diets such as Rhodophyta sp.40 and thus potentially having also high LC-PUFA biosynthetic capacity as its herbivore counterpart S. canaliculatus29,38. Interestingly, S. salpa was chosen for this study to enable us to compare its Fads2 function with those of the carnivorous Sparidae counterparts, A. schlegelii and S. aurata (trophic levels of 3.2 ± 0.45 and 3.7 ± 0.0, respectively) (Table 2), whose diets consist of marine invertebrates that are naturally rich in LC-PUFA41. Despite the markedly different trophic levels existing among these Sparidae species, S. salpa Fads2 was functionally characterised as a Δ6 desaturase like those from S. aurata and A. schlegelii42,43. These results suggest that, rather than trophic level as we initially hypothesised, phylogeny of the species might be a more important factor influencing Fads2 regioselectivity and, ultimately, the species’ ability for LC-PUFA biosynthesis. In agreement, certain teleost families such as Cichlidae include species with two functionalised Fads2, namely a Δ4 desaturase35 and a Δ6Δ5 desaturase30, which appear to be present across the entire family35. Similarly, the presence of Δ4 Fads2 reported herein in A. presbyter and P. lascaris (Table 2), is consistent with this desaturase type also being present in species within their corresponding orders, namely C. estor (Atheriniformes) and S. senegalensis (Pleuronectiformes)18,19,21. Interestingly, while members of the Soleidae species like S. senegalensis and P. lascaris possess Fads2 with Δ4 activity, Scophthalmidae species such as S. maximus and P. olivaceus have a Δ6 Fads219,42. While characterisation of further Fads2 from species within other teleost orders is required to establish more fully the distribution of functionalised Fads2 within this vertebrate clade, it is becoming apparent that the occurrence of Fads2 with a non-Δ6 phenotype is more common than initially anticipated, and instances of functionalised Fads2 have occurred in basal teleost lineages such us Osteoglossomorpha25.

It is still unclear which aa residues of teleost Fads2 are responsible for the dual Δ6Δ5 desaturase phenotype reported in some species25. However, the aa sequence of a particular region in Fads2 located within the second and third histidine boxes has been identified as crucial for the regioselectivity of Δ4 Fads235,39. In the present study, both Δ4 Fads2 characterised from A. presbyter and P. lascaris contained the specific aa residues YXXN that account for the Δ4 activity in Fads2 enzymes35,39. This is consistent with the pattern found in Δ4 Fads2 from S. canaliculatus, S. senegalensis, O. niloticus and O. latipes21,24,26,29,30,35 but differs from the YXXQ regioselectivity region of the Δ4 Fads2 from C. striata10,34. In contrast, the regioselectivity region of the Fads2 characterised from S. salpa and C. labrosus contained FXXQ, which is consistent with other Δ6 Fads2 from R. canadum, Gadus morhua, S. salar and Arapaima gigas20,44,45,46. Interestingly, Fads2 desaturases with the FXXQ sequence also include the bifunctional Δ6Δ5 desaturases from D. rerio28, S. canaliculatus29 and C. striata10 and, thus, this sequence is not useful to predict function of teleost Fads2.

Monroig et al.26 established that Δ8 desaturase capacity is an intrinsic feature among teleost Fads2. We herein investigated the ability of the Fads2 for Δ8 desaturation and concluded that Δ6 Fads2 from S. salpa and C. labrosus were also Δ8 desaturases. These results are in agreement with virtually all Fads2 with Δ6 or Δ6Δ5 desaturation capabilities also having Δ8 activity10,18,19,25,26,31,33. In contrast, Fads2 from P. lascaris and A. presbyter, characterised as Δ4 desaturases in the present study, did not show Δ8 desaturase activity, consistent with such an ability also being absent in Δ4 Fads2 from C. estor18 and C. striata34. Crystalline structure is available for two mammalian stearoyl-CoA desaturases47,48 but, unfortunately, is lacking for Fads-like desaturases such as those studied herein. Therefore, it is not yet possible to understand the catalytic mechanism by which Δ8 desaturation ability is retained in some Fads2, but lost in neofunctionalised Δ4 Fads2. Additionally, from a metabolic standpoint, it is difficult to explain what advantage might be associated with having Fads2 enabling two alternative routes (i.e. Δ6 and Δ8 pathways), but which do not overcome the lack of Δ5 desaturation capacity required for EPA and ARA biosynthesis. Indeed, Δ5 desaturase appears to also be limiting the LC-PUFA biosynthetic capacity in P. lascaris and A. presbyter that, despite having Δ4 desaturases, did not show any Δ5 desaturase activity. All the implications discussed herein should be taken with caution considering that other Fads2 might exist within these species’ genomes. Further studies are required to confirm the presence and functions of further Fads2 with potentially complementary roles to those of the Fads2 characterised in the present study.

The analysis of fads2 tissue expression showed significant differences within each species. The four species are all of marine origin, with two out of the four (S. salpa and P. lascaris) displaying the highest number of mRNA copies in brain and liver and also in intestine from P. lascaris. This is generally in agreement with these tissues being major metabolic sites for LC-PUFA biosynthesis in fish19,30,31,37,45,46,49,50,51. In general, freshwater fish species have been shown to express highest fads2 expression levels in liver and intestine10,17,18,52, with marine species often having brain as the tissue with the highest expression17. Nevertheless, this is a broad generalisation since, in addition to habitat (freshwater vs. marine), other factors such as developmental stage, nutritional history, reproductive status, etc., can influence the tissue distribution patterns of fish fads217. Unfortunately, the impact that these factors might have had on the specimens used in our tissue distribution analyses could not be determined, and thus we are unable to clarify whether any correlations exist between our expression data and the species’ trophic level.

In conclusion, the data indicated that trophic level does not appear to be the primary determinant of Fads2 activity and does not, by itself, explain cases of functionalisation within the Fads2 protein family. In the herbivorous Sparidae species S. salpa, the Fads2 functions were found to be very similar to those previously reported in Fads2 from carnivorous counterpart species such as S. aurata and A. schlegelii. Instances of functionalised Fads2 with Δ4 desaturase activity enabling enhanced LC-PUFA biosynthesis were found in higher trophic level species, despite the fact that the essential FA requirements of these species can likely be fully satisfied by their natural diets.

Methods

This study was conducted in accordance with the regulations within Spanish law 6/2013 based on Directive 2010/63/EU of the European Parliament on animal welfare and the protection of animals used for scientific purposes. The experiment was authorised by the Ethics Committee of University of La Laguna (Spain) and the Animal Welfare and Ethical Review Board of University of Stirling (UK).

Fish and tissue collection

Four individual specimens of salema (S. salpa), thicklip grey mullet (C. labrosus), sand sole (P. lascaris) and sand smelt (A. presbyter), were net caught by local fishermen. These species occupy different trophic levels: 2.0 ± 0.0 (herbivore, S. salpa), 2.6 ± 0.32 (omnivore, C. labrosus), 3.3 ± 0.1 (carnivore, P. lascaris) and 3.7 ± 0.4 (carnivore, A. presbyter)41. The S. salpa, C. labrosus, and A. presbyter specimens were captured off the coast of Tenerife (Spain), whereas P. lascaris was captured off the coast of Huelva (Spain) (Supplementary Table S1). Fish were killed after anesthesia by percussive blow to the head prior to collection of tissues including brain, gill, intestine (specifically foregut), heart, liver and muscle. The tissue samples (~100 mg for S. salpa, C. labrosus and P. lascaris, and ~50 mg for A. presbyter) were immediately placed in tubes containing RNAlater (Qiagen Iberia S.L., Spain), and maintained at 4 °C for 24 h prior to being frozen at −20 °C until analysis.

Molecular cloning of fads2 cDNAs

Total RNA was extracted from each tissue of each species using TRI Reagent (Sigma-Aldrich, UK) according to the manufacturer’s instructions using a bead tissue disruptor (Bio Spec, USA). For each species, first-strand complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesised from 2 µg of total RNA from brain and liver (1:1 mixture) using High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (AB Applied Biosystems, USA). In order to obtain the first fragments of fads2 genes by polymerase chain reaction (PCR), the cDNA was used as template together with degenerated primers (Supplementary Table S2) and GoTaq® Green Master Mix (Promega, UK). Degenerate primers were designed on conserved regions of teleost fads2 sequences obtained using the NCBI blastn tool (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/), specifically G. morhua (DQ054840.2), S. senegalensis (JN673546.1), S. aurata (AY055749.1), Epinephelus coioides (EU715405.1), Rachycentron canadum (FJ440238.1), S. canaliculatus (EF424276.2), and C. estor (KJ417838.1 and KJ417839.1), which were then aligned with BioEdit v7.0.9 (Tom Hall, Department of Microbiology, North Carolina State University, USA). PCR were performed by an initial denaturing step at 95 °C for 2 min, followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 30 s, annealing at 58–62 °C for 30 s and extension at 72 °C for 1 min and 30 s, followed by a final extension at 72 °C for 5 min (Supplementary Table S3). The PCR fragments were purified on agarose gels using IllustraTM GFXTM PCR DNA and Gel Band Purification kit (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, UK), cloned into pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega, UK) and sequenced (GATC Biotech, Germany).

The obtained sequences were used to design specific primers for 5′ and 3′ Rapid Amplification of cDNA Ends (RACE) PCR to obtain full-length cDNA sequences of fads2 (FirstChoice® RLM-RACE kit, Ambion, Applied Biosystems, UK). Details of all primers used for RACE PCR are provided in Supplementary Table S2. For 3′RACE PCR, a positive fragment was obtained for fads2 by two-round PCR (see conditions in Supplementary Table S3). In the first round PCR, 3′RACE outer primer and gene-specific primers for each species were used, using 3′RACE cDNA as a template. In the second round, the first-round product of the putative fads2 from each species was used as a template for nested PCR along with 3′RACE inner primer and gene-specific primers. For 5′RACE PCR (Supplementary Table S3), a similar procedure was followed, with the first round PCR using 5′RACE cDNA as template run with 5′RACE outer primer and gene-specific primers (Supplementary Table S2). The second round PCR used 5′RACE inner and gene-specific primers (Supplementary Table S2) and the first round RACE PCR products as a template (see conditions in Supplementary Table S3). Both 3′ and 5′ RACE PCR fragments of each species’ fads2 were purified, cloned and sequenced as described above.

Sequence and phylogenetic analyses

The deduced amino acid (aa) sequences of putative Fads2 proteins isolated from A. presbyter, C. labrosus, P. lascaris and S. salpa were aligned with multiple functionally characterised Fads2 desaturases using MAFFT (https://mafft.cbrc.jp/alignment/software/) Ver. 7.38853 with the G-INS-I method. The obtained alignment was then cropped to remove columns containing gaps in 95% or more of the sequences. The maximum likelihood (ML) phylogenetic analysis was performed using PhyML v3.0 server54. The evolutionary model of protein used for constructing the tree was JTT + G + I, which was selected by Smart Model Selection (SMS) with Bayesian information criterion55 (BIC). The branch supporting values were calculated from 1000 bootstrap replicates. The resultant ML tree was visualised using CLC Main Workbench 8.0 (CLC bio, Denmark).

Functional characterisation of the Fads2 by heterologous expression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae

The open reading frames (ORF) of the fads2 cloned from A. presbyter, C. labrosus, P. lascaris and S. salpa were amplified from liver cDNA using a nested PCR approach. The first round PCR was run using primer pairs designed in the 5′ and 3′ untranslated regions (UTR) for forward and reverse primers, respectively (Supplementary Table S2). The second round PCR was run using the first round PCR products as templates and primers containing the restriction enzymes BamHI/XhoI for A. presbyter and P. lascaris fads2, and HindIII/XhoI for C. labrosus and S. salpa fads2 (underlined in Supplementary Table S2). Both first and second round PCR were performed with the high fidelity Pfu DNA polymerase (Promega, UK) for fads2 from A. presbyter, C. labrosus and P. lascaris, and PfuUltra II Fusion HS DNA Polymerase (Agilent, USA) for S. salpa fads2. Further details on PCR conditions used to amplify fads2 ORF sequences are given in Supplementary Table S3. The PCR products were subsequently purified as described above, digested with the corresponding restriction enzymes (New England BioLabs, UK) and ligated into a similarly restricted pYES2 yeast expression vector (Thermo Fisher Scientific, UK). The plasmids containing pYES2-fads2 from each species were sequenced before being transformed into yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae competent cells InvSc1 (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Transformation and selection of yeast culture were performed as described previously20,56. One single yeast colony transformed with pYES2-fads2 for each species was used in each functional assay. The transgenic yeasts were grown in the presence of FA substrates for Δ6 (18:2n-6 and 18:3n-3), Δ8 (20:2n-6 and 20:3n-3), Δ5 (20:3n-6 and 20:4n-3) and Δ4 (22:4n-6 and 22:5n-3) desaturases. The FA substrates were added to the yeast cultures at final concentrations of 0.5 mM for C18 PUFA 0.75 mM for C20 PUFA and 1.0 mM for C22 PUFA, as uptake efficiency decreases with increasing chain length44. In addition, yeasts transformed with empty pYES2 were also grown in the presence of each substrate as control treatments. After 2 days of culture at 30 °C, yeasts were harvest, washed, and total lipid extracted by homogenisation in chloroform/methanol (2:1, v/v) containing 0.01% (w/v) butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT) as antioxidant.

Fatty acid analysis of yeast

Fatty acid methyl esters (FAME) were prepared from total lipid extracted from yeast according to Hastings et al.28. FAME were separated and quantified using a Fisons GC-8160 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) gas chromatograph equipped with a 60 m × 0.32 mm i.d. × 0.25 μm ZB-wax column (Phenomenex, UK) and flame ionisation detector57. The desaturation conversion efficiencies from exogenously added PUFA substrates were calculated by the proportion of substrate fatty acid converted to desaturated products as [product area/(product area + substrate area)] × 100.

Tissue expression of fads2 in each species

Expression of the fads2 genes was determined by quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) in brain, gill, intestine, heart, liver and muscle. Replicate numbers were n = 4 in each species except for brain of C. labrosus and A. presbyter (n = 3 and n = 2, respectively), heart of S. salpa and A. presbyter (n = 3 and n = 1, respectively) and muscle of S. salpa (n = 3). Elongation factor-1α (elf1α) and β-actin were used as reference genes to normalise the expression of fads2. For each tissue 2 µg of total RNA were reverse transcribed into cDNA as described above. In order to determine the efficiency of the primer pairs, serial dilutions of pooled cDNA from all four tissues were carried out. All qPCR were performed by a Biometra TOptical Thermocycler (Analytik Jena, Germany) in 96-well plates in duplicates at total volume of 20 µL containing 10 µL of Luminaris Color HiGreen qPCR Master Mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific), 1 µL of each primer (10 µM), 2 µL or 5 µL of cDNA (1/20 dilutions) for reference and target genes respectively, as well as 6 or 3 µL of molecular biology grade water. Besides, negative controls (NTC, no template control), containing molecular biology grade water instead of cDNA, were also run. The primer sequences and qPCR conditions are detailed in Supplementary Tables S2 and S3, respectively. The relative expression of fads2 among tissues in each species was calculated as arbitrary units after normalisation dividing by the geometric mean of the expression level of the reference genes elf1α and β-actin. One arbitrary unit is defined as the ratio between the expression level of fads2 and the lowest expression level for this gene. After each qPCR analysis, a melting curve with 1 °C increments during 6 s from 60 to 95 °C was performed, in order to check the presence of a single product in each reaction.

Statistical analysis

Tissue expression results are presented as log 10 mean normalised ratios ± standard error. Data were checked for normal distribution with the one-sample Shapiro-Wilk test, as well as for homogeneity of the variances with the Levene’s test58. A one-way ANOVA test was performed within each species for tissue expression factor, followed by a Tukey HSD multiple comparison test58. When normal distribution and/or homoscedasticity were not achieved, data were subjected to Kruskall-Wallis non-parametric test, followed by Pairwise Wilcoxon Rank Sum Tests58. Statistical analysis was carried out in tissues from at least three replicates, and their significance was established at P < 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using the R software (R Core Team, Austria).

References

Calder, P. C. Very long-chain n-3 fatty acids and human health: fact, fiction and the future. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 77, 52–72 (2018).

Hadley, K. B., Ryan, A. S., Forsyth, S., Gautier, S. & Salem, N. The essentiality of arachidonic acid in infant development. Nutrients 8 (2016).

Weiser, M. J., Butt, C. M. & Mohajeri, M. H. Docosahexaenoic acid and cognition throughout the lifespan. Nutrients 8, 99 (2016).

Zárate, R., el Jaber-Vazdekis, N., Tejera, N., Pérez, J. A. & Rodríguez, C. Significance of long chain polyunsaturated fatty acids in human health. Clin. Transl. Med. 6, 25 (2017).

Lee, J., Lee, H., Kang, S. & Park, W. Fatty acid desaturases, polyunsaturated fatty acid regulation, and biotechnological advances. Nutrients 8, 23 (2016).

Khozin-Goldberg, I., Iskandarov, U. & Cohen, Z. LC-PUFA from photosynthetic microalgae: occurrence, biosynthesis, and prospects in biotechnology. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 91, 905 (2011).

Pereira, S. L., Leonard, A. E. & Mukerji, P. Recent advances in the study of fatty acid desaturases from animals and lower eukaryotes. Prostaglandins, Leukot. Essent. Fat. Acids 68, 97–106 (2003).

Kabeya, N. et al. Genes for de novo biosynthesis of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids are widespread in animals. Sci. Adv. 4 (2018).

da Costa, E. et al. High-resolution lipidomics of the early life stages of the red seaweed Porphyra dioica. Molecules 23, 187 (2018).

Kuah, M.-K., Jaya-Ram, A. & Shu-Chien, A. C. A fatty acyl desaturase (fads2) with dual Δ6 and Δ5 activities from the freshwater carnivorous striped snakehead Channa striata. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 201, 146–155 (2016).

Béné, C. et al. Feeding 9 billion by 2050–Putting fish back on the menu. Food Secur. 7, 261–274 (2015).

Sprague, M., Dick, J. R. & Tocher, D. R. Impact of sustainable feeds on omega-3 long-chain fatty acid levels in farmed Atlantic salmon, 2006–2015. Sci. Rep. 6, 21892 (2016).

Betancor, M. B. et al. A nutritionally-enhanced oil from transgenic Camelina sativa effectively replaces fish oil as a source of eicosapentaenoic acid for fish. Sci. Rep. 5, 8104 (2015).

Betancor, M. B. et al. Replacement of marine fish oil with de novo omega-3 oils from transgenic Camelina sativa in feeds for gilthead Sea Bream (Sparus aurata L.). Lipids 51, 1171–1191 (2016).

Oliva-Teles, A., Enes, P. & Peres, H. Replacing fishmeal and fish oil in industrial aquafeeds for carnivorous fish. in Feed and Feeding Practices in Aquaculture (ed. Allen, D.) 203–233 (Elsevier, 2015).

Castro, L. F. C., Tocher, D. R. & Monroig, O. Long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acid biosynthesis in chordates: Insights into the evolution of Fads and Elovl gene repertoire. Prog. Lipid Res. 62, 25–40 (2016).

Monroig, O., Tocher, D. R. & Castro, L. F. C. Polyunsaturated fatty acid biosynthesis and metabolism in fish. in Polyunsaturated Fatty Acid Metabolism (ed. Burdge, G.) 31–60 (AOCS Press, 2018).

Fonseca-Madrigal, J. et al. Diversification of substrate specificities in teleostei Fads2: characterization of Δ4 and Δ6Δ5 desaturases of Chirostoma estor. J. Lipid Res. 55, 1408–1419 (2014).

Kabeya, N., Chiba, M., Haga, Y., Satoh, S. & Yoshizaki, G. Cloning and functional characterization of fads2 desaturase and elovl5 elongase from Japanese flounder Paralichthys olivaceus. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part B Biochem. Mol. Biol. 214, 36–46 (2017).

Monroig, Ó. et al. Multiple genes for functional 6 fatty acyl desaturases (Fad) in Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar L.): Gene and cDNA characterization, functional expression, tissue distribution and nutritional regulation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 1801, 1072–1081 (2010).

Morais, S., Castanheira, F., Martinez-Rubio, L., Conceição, L. E. C. & Tocher, D. R. Long chain polyunsaturated fatty acid synthesis in a marine vertebrate: Ontogenetic and nutritional regulation of a fatty acyl desaturase with Δ4 activity. Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 1821, 660–671 (2012).

Park, H. G., Park, W. J., Kothapalli, K. S. & Brenna, J. T. The fatty acid desaturase 2 (FADS2) gene product catalyzes Δ4 desaturation to yield n-3 docosahexaenoic acid and n-6 docosapentaenoic acid in human cells. FASEB J 29, 3911–9 (2015).

Sprecher, H. Metabolism of highly unsaturated n-3 and n-6 fatty acids. Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 1486, 219–231 (2000).

Castro, L. F. C. et al. Functional desaturase Fads1 (Δ5) and Fads2 (Δ6) orthologues evolved before the origin of jawed vertebrates. PLoS One 7, e31950 (2012).

Lopes-Marques, M. et al. Retention of fatty acyl desaturase 1 (fads1) in Elopomorpha and Cyclostomata provides novel insights into the evolution of long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acid biosynthesis in vertebrates. BMC Evol. Biol., https://doi.org/10.1186/s12862-018-1271-5

Monroig, Ó., Li, Y. & Tocher, D. R. Delta-8 desaturation activity varies among fatty acyl desaturases of teleost fish: High activity in delta-6 desaturases of marine species. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. - B Biochem. Mol. Biol. 159, 206–213 (2011).

Park, W. J., Kothapalli, K. S. D., Lawrence, P., Tyburczy, C. & Brenna, J. T. An alternate pathway to long-chain polyunsaturates: the FADS2 gene product Delta8-desaturates 20:2n-6 and 20:3n-3. J. Lipid Res. 50, 1195–202 (2009).

Hastings, N. et al. A vertebrate fatty acid desaturase with Delta 5 and Delta 6 activities. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 14304–9 (2001).

Li, Y. et al. Vertebrate fatty acyl desaturase with Δ4 activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107, 16840–16845 (2010).

Tanomman, S., Ketudat-Cairns, M., Jangprai, A. & Boonanuntanasarn, S. Characterization of fatty acid delta-6 desaturase gene in Nile tilapia and heterogenous expression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part B Biochem. Mol. Biol. 166, 148–156 (2013).

Oboh, A., Betancor, M. B., Tocher, D. R. & Monroig, O. Biosynthesis of long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids in the African catfish Clarias gariepinus: Molecular cloning and functional characterisation of fatty acyl desaturase (fads2) and elongase (elovl2) cDNAs7. Aquaculture 462, 70–79 (2016).

Janaranjani, M. et al. Capacity for eicosapentaenoic acid and arachidonic acid biosynthesis in silver barb (Barbonymus gonionotus): Functional characterisation of a Δ6/Δ8/Δ5 Fads2 desaturase and Elovl5 elongase. Aquaculture 497, 469–486 (2018).

Ferraz, R. B. et al. A complete enzymatic capacity for long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acid biosynthesis is present in the Amazonian teleost tambaqui, Colossoma macropomum. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part B Biochem. Mol. Biol. 227, 90–97 (2018).

Kuah, M.-K., Jaya-Ram, A. & Shu-Chien, A. C. The capacity for long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acid synthesis in a carnivorous vertebrate: Functional characterisation and nutritional regulation of a Fads2 fatty acyl desaturase with Δ4 activity and an Elovl5 elongase in striped snakehead (Channa striata). Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 1851, 248–260 (2015).

Oboh, A. et al. Two alternative pathways for docosahexaenoic acid (DHA, 22:6n-3) biosynthesis are widespread among teleost fish. Sci. Rep. 7, 3889 (2017).

Hastings, N. et al. Molecular Cloning and functional characterization of fatty acyl desaturase and elongase cDNAs involved in the production of eicosapentaenoic and docosahexaenoic acids from α-linolenic acid in Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar). Mar. Biotechnol. 6, 463–474 (2004).

Abdul Hamid, N. K. et al. Isolation and functional characterisation of a fads2 in Rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) with Δ5 desaturase activity. PLoS One 11, e0150770 (2016).

Monroig, Ó. et al. Elongation of long-chain fatty acids in rabbitfish Siganus canaliculatus: Cloning, functional characterisation and tissue distribution of Elovl5- and Elovl4-like elongases. Aquaculture 350–353, 63–70 (2012).

Lim, Z. L., Senger, T. & Vrinten, P. Four amino acid residues influence the substrate chain-length and regioselectivity of Siganus canaliculatus Δ4 and Δ5/6 desaturases. Lipids 49, 357–367 (2014).

Antolić, B., Skaramuca, B., Špan, A., Mušin, D. & Sanko-Njire, J. Food and feeding habits of a herbivore fish Sarpa salpa (L.)(Teleostei, Sparidae) in the southern Adriatic (Croatia). Acta Adriat. 35, 45–52 (1994).

Froese, R. & Pauly, D. FishBase. World Wide Web electronic publication (2018).

Zheng, X. et al. Characterization and comparison of fatty acyl Δ6 desaturase cDNAs from freshwater and marine teleost fish species. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part B Biochem. Mol. Biol. 139, 269–279 (2004).

Kim, S. H. et al. Functional characterization of a delta 6-desaturase gene from the black seabream (Acanthopagrus schlegeli). Biotechnol. Lett. 33, 1185–1193 (2011).

Lopes-Marques, M. et al. Molecular and functional characterization of a fads2 orthologue in the Amazonian teleost, Arapaima gigas. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part B Biochem. Mol. Biol. 203, 84–91 (2017).

Zheng, X. et al. Physiological roles of fatty acyl desaturases and elongases in marine fish: Characterisation of cDNAs of fatty acyl Δ6 desaturase and elovl5 elongase of cobia (Rachycentron canadum). Aquaculture 290, 122–131 (2009).

Tocher, D. R. et al. Highly unsaturated fatty acid synthesis in marine fish: Cloning, functional characterization, and nutritional regulation of fatty acyl Δ6 desaturase of Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua L.). Lipids 41, 1003–1016 (2006).

Bai, Y. et al. X-ray structure of a mammalian stearoyl-CoA desaturase. Nature 524, 252 (2015).

Wang, H. et al. Crystal structure of human stearoyl–coenzyme A desaturase in complex with substrate. Nat. Struct. &Amp; Mol. Biol. 22, 581 (2015).

Huang, Y. et al. Cloning, tissue distribution, functional characterization and nutritional regulation of Δ6 fatty acyl desaturase in chu’s croaker Nibea coibor. Aquaculture 479, 208–216 (2017).

Xu, H. et al. Regulation of tissue LC-PUFA contents, Δ6 fatty acyl desaturase (FADS2) gene expression and the methylation of the putative FADS2 gene promoter by different dietary fatty acid profiles in Japanese seabass (Lateolabrax japonicus). PLoS One 9, e87726 (2014).

Betancor, M. B., Ortega, A., de la Gándara, F., Tocher, D. R. & Mourente, G. Lipid metabolism-related gene expression pattern of Atlantic bluefin tuna (Thunnus thynnus L.) larvae fed on live prey. Fish Physiol. Biochem. 43, 493–516 (2017).

Geay, F. et al. Cloning and functional characterization of Δ6 fatty acid desaturase (FADS2) in Eurasian perch (Perca fluviatilis). Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part B Biochem. Mol. Biol. 191, 112–125 (2016).

Katoh, K., Rozewicki, J. & Yamada, K. D. MAFFT online service: multiple sequence alignment, interactive sequence choice and visualization. Brief. Bioinform. bbx108–bbx108 (2017).

Guindon, S. et al. New algorithms and methods to estimate maximum-likelihood phylogenies: Assessing the performance of PhyML 3.0. Syst. Biol. 59, 307–321 (2010).

Lefort, V., Longueville, J.-E. & Gascuel, O. SMS: Smart Model Selection in PhyML. Mol. Biol. Evol. 34, 2422–2424 (2017).

Agaba, M., Tocher, D. R., Dickson, C. A., Dick, J. R. & Teale, A. J. Zebrafish cDNA encoding multifunctional fatty acid elongase involved in production of eicosapentaenoic (20:5n-3) and docosahexaenoic (22:6n-3) acids. Mar. Biotechnol. 6, 251–261 (2004).

Kabeya, N. et al. Biosynthesis of polyunsaturated fatty acids in sea urchins: Molecular and functional characterisation of three fatty acyl desaturases from Paracentrotus lividus (Lamark 1816). PLoS One 12, e0169374 (2017).

McDonald, J. H. Handbook of Biological Statistics. (Sparky House Publishing, 2014).

Acknowledgements

The present study was funded by Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad (AGL2015-70994-R). Dr Covadonga Rodríguez is a member of the Instituto de Biotecnología de Canarias (ITB).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.G., C.R. and Ó.M. designed research; D.G., N.K., M.B.B., J.A.P. and N.G.A. performed research; D.G., N.K., D.R.T. and C.R. analysed data; Ó.M., D.G. and C.R. wrote the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Garrido, D., Kabeya, N., Betancor, M.B. et al. Functional diversification of teleost Fads2 fatty acyl desaturases occurs independently of the trophic level. Sci Rep 9, 11199 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-47709-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-47709-0

This article is cited by

-

Chitosan-based delivery of fish codon-optimised Caenorhabditis elegans FAT-1 and FAT-2 boosts EPA and DHA biosynthesis in Sparus aurata

Reviews in Fish Biology and Fisheries (2024)

-

Capability of DHA biosynthesis in a marine teleost, Pacific saury Cololabis saira: functional characterization of two paralogous Fads2 desaturases and Elovl5 elongase

Fisheries Science (2023)

-

A complete inventory of long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acid biosynthesis pathway enzymes in the miniaturized cyprinid Paedocypris micromegethes

Fish Physiology and Biochemistry (2022)

-

Lack of ∆5 Desaturase Activity Impairs EPA and DHA Synthesis in Fish Cells from Red Sea Bream and Japanese Flounder

Marine Biotechnology (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.