Abstract

Research has shown that chitosan induces plant stress tolerance and protection, but few studies have explored chemical modifications of chitosan and their effects on plants under water stress. Chitosan and its derivatives were applied (isolated or in mixture) to maize hybrids sensitive to water deficit under greenhouse conditions through foliar spraying at the pre-flowering stage. After the application, water deficit was induced for 15 days. Analyses of leaves and biochemical gas exchange in the ear leaf were performed on the first and fifteenth days of the stress period. Production attributes were also analysed at the end of the experiment. In general, the application of the two chitosan derivatives or their mixture potentiated the activities of the antioxidant enzymes superoxide dismutase, catalase, ascorbate peroxidase, glutathione reductase and guaiacol peroxidase at the beginning of the stress period, in addition to reducing lipid peroxidation (malonaldehyde content) and increasing gas exchange and proline contents at the end of the stress period. The derivatives also increased the content of phenolic compounds and the activity of enzymes involved in their production (phenylalanine ammonia lyase and tyrosine ammonia lyase). Dehydroascorbate reductase and compounds such as total soluble sugars, total amino acids, starch, grain yield and harvest index increased for both the derivatives and chitosan. However, the mixture of derivatives was the treatment that led to the higher increase in grain yield and harvest index compared to the other treatments. The application of semisynthetic molecules derived from chitosan yielded greater leaf gas exchange and a higher incidence of the biochemical conditions that relieve plant stress.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The increase in the world population, associated with the increase in agricultural production, has caused a series of negative environmental changes to the planet. Climatic changes lead to severe droughts that interfere with the physiological cycle of many cultivated plants. In addition, high temperatures have reached most maize-producing countries. Maize is a crop of great economic importance, as it is used for both human and animal consumption. Abiotic stresses such as drought are considered the most limiting crop production factors around the world1.

Water stress is among the most severe abiotic stresses for maize production. A few days of water deficit in the vegetative stage leads to a decrease in photosynthetically active leaf area in addition to inhibition of root growth. At the flowering stage, this abiotic stress can decrease grain yield and can reach losses of 20 to 50% due to floral abortion, silk desiccation, poor floral synchronization and a decrease in the formation of sinks2.

Most regions that grow maize do not have irrigation technologies available. In the world in general, as well as in Brazil, irrigation is not a totally viable technique, since it is necessary to seek sustainable alternatives that minimize water use in agricultural crops. This type of crop is always exposed and dependent on water-related factors3.

Soil water limitation induces plant stress, decreases cell volume, inhibits Calvin cycle enzymes, causes damage to the photosynthetic apparatus, decreases carbon assimilation and, consequently, decreases yield4.

Radiation in plants with inhibited of Calvin cycle enzymes (due to drought) causes excess energy in the antenna complex of photosystems, a process by which chlorophylls receive a large amount of energy and photoprotective pigments such as carotenoids and xanthophylls, preventing them from dissipating photochemical energy in the form of heat, thus dissipating this energy to oxygen, forming reactive oxygen species (ROS), which, in large amounts, generate oxidative stress that can lead to plant death5.

ROS are found at small concentrations in cellular organelles, such as chloroplasts, mitochondria or peroxisomes, or as by-products of photosynthesis, photorespiration or respiration5. However, in water stress and in the presence of radiation, the production of these compounds is exaggerated, leading to damage to the plasma membrane (lipid peroxidation) and degradation of pigments, proteins and DNA6.

The control of stable ROS levels in cell compartments and in stress situations is or may be maintained by the action of enzymatic (superoxide dismutase, ascorbate peroxidase, catalase, glutathione reductase, polyphenol oxidase, L-phenylalanine ammonia lyase, guaiacol peroxidase and dehydroascorbate reductase) and non-enzymatic (phenolic compounds, α-tocopherol, ascorbic acid, among others) antioxidant mechanisms7,8.

To control water stress, plants also activate osmotic adjustment mechanisms, an efficient physiological process for cellular turgescence, under conditions of low soil water potential9. This mechanism leads to the accumulation of solutes such as proline, glycine betaine, trehalose, and sucrose, among others, in the cytosol or cell vacuole10.

In search of sustainable agriculture techniques with less impact on the environment, research has sought to relieve water stress with the use of biopolymers such as chitin/chitosan, as they have low or no toxicity to the environment and can yield tolerance to water deficits11. Chitin is the second most abundant polysaccharide in nature, and its deacetylation results in chitosan, which has been used on several agricultural crops, including maize12,13, due to its potential as an elicitor, and its antifungal, protective and water stress relief abilities14,15.

Chitosan has a nucleophilic behaviour, making it suitable for structural chemical modifications; among these main modifications, acetylation, quaternization, alkylation, carboxylation, acylation, sulfonation and amidation can be obtained16. The synthesis of chitosan derivatives by the insertion of functional groups into the polymer chain gives this polymer different properties, allowing its use in medical, biotechnological, and agricultural areas14,15,17. However, in agriculture, few studies are based on chitosan derivatives. These derivatives are molecules that can potentiate activity since chitosan itself has important functions in the induction of tolerance to water deficit18.

Therefore, considering the economic importance of the maize crop and the constant harvest losses due to the water resource, the objective of this study was to apply new chitosan derivatives (N-succinyl and N, O-dicarboxymethylated) and to evaluate gas exchange, the antioxidant system and the primary metabolism in maize hybrids sensitive to water deficit.

In this study, we hypothesized that the application of N-succinyl chitosan and N, O- dicarboxymethylated chitosan derivatives or the mixture of the two would be capable of inducing tolerance to water deficit in stress-sensitive maize, associated with effective antioxidant protection through enzymatic and non-enzymatic defence mechanisms.

Results

Quantification of malonaldehyde (MDA) and the enzymatic system

On the first day of water deficit imposition, the content of MDA was reduced in the treatments with the application of the derivatives (WD + SUC) and (WD + MCA) when compared to the WD treatment (Fig. 1A). After 15 days of water deficit, the content of MDA was reduced in the treatments with the application of the mixture of the derivatives (WD + MS) and chitosan (WD + CHI).

Concentration of MDA (A) and activity of the enzymes superoxide dismutase (SOD) (B), catalase (CAT) (C) and ascorbate peroxidase (APX) (D) during 15 days of water deficit in the maize hybrid BRS 1030 after the application of chitosan and its derivatives. Means followed by the same uppercase letter for treatments with 1 day of water deficit and lowercase for treatments with 15 days of water deficit do not differ by the Scott-Knott test at 5% probability (P ≤ 0.05). Each bar indicates the mean ± S.E. IR, irrigated; WD, water deficit; WD + SUC, water deficit with foliar application of SUC; WD + MCA, water deficit with foliar application of MCA; WD + MS, water deficit with foliar application of SUC and MCA; WD + CHI, water deficit with foliar application of chitosan.

For the antioxidant system, it can be observed that the activity of SOD (Fig. 1B) increased with the application of the MCA derivative and the mixture of the two derivatives, followed by chitosan and the SUC derivative. After 15 days of water deficit imposition, the activity of the enzyme did not show significant differences among treatments. On the other hand, the activity of the enzyme catalase (CAT) (Fig. 1C) with one day of water deficit increased in treatments (WD + SUC), (WD + MCA) and (WD + MS), and after 15 days, catalase had its highest activity in the treatment (WD + SUC) when compared with WD.

At the beginning of the water deficit, the enzyme APX (Fig. 1D) showed a higher activity in treatment (WD + SUC). At the end of the water deficit (15 days), APX showed an increase in its activity in all treatments with the application of the derivatives and chitosan.

The activity of GPX (Fig. 2A) increased with the application of the derivatives (WD + SUC) and (WD + MS) after 1 day of water deficit when compared to treatment (WD). With 15 days of water deficit, GPX activity increased in the (WD + SUC), (WD + MS) and (WD + CHI) treatments. The activity of GR (Fig. 2B) after 1 day of water deficit increased only in the mixture of the derivatives (WD + MS); however, after 15 days, GR activity increased in all treatments with the application of the derivatives and chitosan. The activity of DHAR (Fig. 2C) increased in all treatments with the application of chitosan and its derivatives on the first and last days of water deficit.

Activity of guaiacol peroxidase (GPX) (A), glutathione reductase (GR) (B) and dehydroascorbate reductase (DHAR) (C) during 15 days of water deficit in the maize hybrid BRS 1030 after the application of chitosan and its derivatives. Means followed by the same uppercase letter for treatments with 1 day of water deficit and lowercase for treatments with 15 days of water deficit do not differ by the Scott-Knott test at 5% probability (P ≤ 0.05). Each bar indicates the mean ± S.E. IR, irrigated; WD, water deficit; WD + SUC; water deficit with foliar application of SUC, WD + MCA, water deficit with foliar application of MCA; WD + MS, water deficit with foliar application of SUC and MCA; WD + CHI, water deficit with foliar application of chitosan.

With the imposition of 1 day of water deficit, the enzymes PAL (Fig. 3A) and TAL (Fig. 3B) showed increased activity in all the treatments with the application of the derivatives and of chitosan and showed higher means for the plants that received SUC (WD + SUC) and the mixture (WD + SUC + MCA). On the 15th day of water deficit imposition, the activity of PAL did not show a significant difference among treatments, whereas TAL enzyme showed more activity in the treatments (WD + SUC), followed by (WD + MS) and (WD + CHI).

Activity of L-phenylalanine ammonia lyase (PAL) (A), tyrosine ammonia lyase (TAL) (B) and concentration of phenolic compounds (C) during 15 days of water deficit in the maize hybrid BRS 1030 after the application of chitosan and its derivatives. Means followed by the same uppercase letter for treatments with 1 day of water deficit and lowercase for treatments with 15 days of water deficit do not differ by the Scott-Knott test at 5% probability (P ≤ 0.05). Each bar indicates the mean ± S.E. IR, irrigated; WD, water deficit; WD + SUC, water deficit with foliar application of SUC; WD + MCA, water deficit with foliar application of MCA; WD + MS, water deficit with foliar application of SUC and MCA; WD + CHI, water deficit with foliar application of chitosan.

Phenolic compounds (Fig. 3C) had a higher concentration in the treatments (WD + SUC), (WD + MCA) and (WD + MS) after 1 and 15 days of water deficit when compared to the treatment (DW).

Gas exchange analysis

After 1 day of water deficit, the application of the derivatives and chitosan did not increase the photosynthetic rate (A) (Table 1) in the hybrid BRS 1030 when compared to the irrigated treatment (IR). On the 15th day of water deficit imposition, it was observed that the photosynthetic rate decreased in the treatment (DW). However, the treatments (WD + SUC), (WD + MCA) and (WD + MS) increased the photosynthetic rate compared to the treatment (WD). For stomatal conductance (gs) (Table 1), the same effect was observed as that for the photosynthetic rate, with a decrease in the treatments with derivatives and chitosan at 1 day of water deficit. On the 15th day of water deficit, there was an increase in stomatal conductance for the treatments (WD + SUC), (WD + MCA) and (WD + MS) compared to treatment (WD).

Quantification of proline and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2)

The proline content (Fig. 4A) increased in treatments (WD + MCA), (WD + MS) and (WD + CHI) with the imposition of 1 day of water deficit. On the 15th day, all treatments with the application of the derivatives and chitosan showed a higher concentration of this osmoregulator when compared to treatment (WD).

Concentration of proline (A) and content of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) (B) during 15 days of water deficit in the maize hybrid BRS 1030 after the application of chitosan and its derivatives. Means followed by the same uppercase letter for treatments with 1 day of water deficit and lowercase for treatments with 15 days of water deficit do not differ by the Scott-Knott test at 5% probability (P ≤ 0.05). Each bar indicates the mean ± S.E. IR, irrigated; WD, water deficit; WD + SUC, water deficit with foliar application of SUC; WD + MCA, water deficit with foliar application of MCA; WD + MS, water deficit with foliar application of SUC and MCA; WD + CHI, water deficit with foliar application of chitosan.

The concentrations of H2O2 increased in treatments (WD + SUC), (WD + MCA) and (WD + MS) after 1 day of water deficit. At the end of the water deficit, all treatments with the application of the derivatives and chitosan showed higher H2O2 concentrations when compared to WD (Fig. 4B).

Quantification of total soluble sugars, total amino acids and starch

When analysing the total soluble sugars (Fig. 5A), a higher concentration was observed in all treatments with the application of the derivatives and chitosan at 1 and 15 days of imposition of water deficit. The total amino acids (Fig. 5B) showed a higher concentration in the treatments (WD + SUC), (WD + MS) and (WD + CHI) with 1 day of water deficit. On the 15th day of water deficit, the highest concentrations were found in the treatments (WD + SUC), (WD + MS) and (WD + CHI). The starch content (Fig. 5C) was evidenced at higher concentrations in treatments (WD + MCA), (WD + MS) and (WD + CHI) with 1 day of water deficit. On the 15th day of water stress imposition, all treatments with the application of the derivatives and chitosan had a higher concentration of starch when compared to treatment (WD).

Concentration of total soluble sugars (A), total amino acids (B) and starch (C) during 15 days of water deficit in the maize hybrid BRS 1030 after the application of chitosan and its derivatives. Means followed by the same uppercase letter for treatments with 1 day of water deficit and lowercase for treatments with 15 days of water deficit do not differ by the Scott-Knott test at 5% probability (P ≤ 0.05). Each bar indicates the mean ± S.E. IR, irrigated; WD, water deficit; WD + SUC, water deficit with foliar application of SUC; WD + MCA, water deficit with foliar application of MCA; WD + MS, water deficit with foliar application of SUC and MCA; WD + CHI, water deficit with foliar application of chitosan.

Production components

It was observed that ear weight was higher in the irrigated treatment, and there was no difference between treatments stressed and stressed with the application of biopolymers (Table 2). Irrigated plants presented higher grain yield. However, the plants treated with the mixture of the derivatives (WD + MS) presented higher grain yield than those sprayed with chitosan or the separately applied derivatives. The same result observed in this parameter was also found in the harvest index (Table 2).

Discussion

Water stress is among the most severe stresses on maize production. A few days of water stress at the flowering stage decrease maize yield18. Water deficit causes several reactions in the plant, decreasing its water status (water potential), damaging and altering its photosystems, and increasing reactive oxygen species (ROS), causing degradation of lipid membranes19.

This degradation of the lipid membrane (lipid peroxidation) can be observed by the formation of a secondary metabolite known as MDA. Sensitive maize genotypes under water deficit have a higher MDA content20,21,22. The application of the N-succinyl and N, O-dicarboxymethylated derivatives decreased lipid peroxidation, showing more induction of water deficit tolerance than its initial structure, chitosan. The application of pure chitosan has relieved lipid peroxidation in maize, potato and peach plants23,24,25.

In maize plants tolerant to water deficit, one of the physiological responses to this exposure is the activation of the enzymatic antioxidant system to scavenge ROS20,26. However, sensitive maize genotypes tend not to exhibit this ability to scavenge ROS, in addition to presenting low photosynthetic rates when exposed to extended stress19,20. However, studies have shown that the application of chitosan can induce this antioxidant defences in plants in addition to increasing carbon assimilation27,28,29,30.

In this study, higher antioxidant enzymatic activity (SOD, CAT, APX, GPX and GR) was observed when the chitosan derivatives or their mixture were applied. This increase in enzymatic activity could explain the lower cell damage (lipid peroxidation), higher photosynthetic rate and stomatal conductance in these treatments. In a certain way, chitosan derivatives may have induced a greater tolerance to the hybrid BRS 1030 due to its performance in the physiological and molecular leaf processes.

Studies have shown that chitosan may act on nucleus and chloroplast genes involving increased photosynthetic and enzymatic antioxidant activities31,32. Chitosan has positive ionic charges, which gives it the ability to bind easily with negatively charged lipids, metal ions, proteins, and macromolecules. Although it has positive ionic charges, chitosan activates defence genes through changes in chromatin33. Chitosan has nucleotide sugars (uridine diphosphate N-acetyl-d-glucosamine (UDP-GlcNAc)) in its chemical constitution. When these sugars are applied in plants, the plant cell recognizes this site through the enzymes chitin synthase and chitosan chitin deacetylase. These enzymes recognize the β-1,4-linked N-acetylglucosamine residues and cleave these regions, producing chitosan oligomers that are important signals for plant cells33,34.

These chitosan oligomers arrive in the nucleus and in the chloroplastida and act in cascade reactions, inducing oxidative bursts and the production of hormones and modifying the chromatin and expression of antioxidant enzymes and photosynthetic enzymes28,31,33,35,36,37. A possible reason for the better response of the derivatives analysed in this study is that the oligosaccharides from the cleavage of the MCA and SUC derivatives containing N-succinyl and N, O-dicarboxymethylated groups by chitinases appear to be more active in potentiating enzymatic responses in sensitive maize than oligomers originating only from chitosan. In addition, the new chemical groups that were added to chitosan for the synthesis of derivatives tend to render these compounds more soluble in water38 and may also favour bioavailability.

The increase in H2O2 at the beginning of the water deficit in maize plants may be related to the role of chitosan (and its derivatives) in stress signalling and stomatal limitation (decrease in gs under drought)38,39. The initial production of H2O2 in maize may also be correlated with the activation of antioxidant enzymes20. Chitosan is considered a promoter of stomatal closure in the initial stages of water stress40,41, a fact observed in this study at higher proportions for plants treated with SUC and MCA derivatives on the first day of water deficit. This stomatal limitation occurs once chitosan can induce the production of stress signals such as H2O2 and abscisic acid (ABA)41,42,43,44.

In this study, an association of increased activity of phenylalanine ammonia lyase (PAL) and tyrosine ammonia lyase (TAL) was observed with the increase in the concentration of phenolic compounds. In addition, it is possible to highlight the higher TAL activity at the end of the water stress in the treatment in which the derivatives were applied and higher grain yield occurred. PAL and TAL are enzymes located between the primary and secondary metabolites and are related to the synthesis of the phenylpropanoid pathway, which is important for the synthesis of phenolic compounds45. These enzymes are considered the most important in the regulation of secondary metabolism. PAL is responsible for the production of trans-cinnamic acid and TAL for p-coumaric acid. These acids are incorporated into the formation of different phenolic compounds, which are present in the formation of esters, coumarins, flavonoids and lignins45,46. Maize-tolerant genotypes tend to present higher amounts of these compounds and especially TAL may be involved in this higher production47,48.

Several studies have shown that chitosan promoted increased activity of TAL, PAL and phenolic compounds in the plant antioxidant defence system against abiotic and biotic stresses27,49,50,51.

In this study, SUC and MCA derivatives, besides their mixture induced the production of phenolic compounds, and this provided an important increase in the tolerance of water deficit, even for maize47,52. Phenolic compounds such as flavonoids act in free radical scavenging and protection against oxidative stress in the face of water deficit20,47,52.

Both proline and sugars are important osmoregulators in maize, allowing water to remain inside foliar cells, even under water deficit conditions53,54,55. Chitosan and its derivatives induced greater accumulation of these compounds, favouring the tolerance of the sensitive hybrid (BRS 1030) to water deficit. Under water deficit conditions, the exogenous application of chitosan triggered in Trifolium repens a cascade of reactions that led to a greater tolerance of water deficit. In this experiment, chitosan yielded a greater accumulation of amino acids, sugars, starch, and flavonoids, among other metabolites. These compounds are associated with osmotic adjustment and the antioxidant defences of plants under stress conditions56. Plants that received the chitosan derivatives had higher amounts of amino acids in the leaves, which implies greater nitrogen uptake and/or mobilization or greater efficiency in the use of this nutrient in the plants that may have been favoured by the exogenous reception of the chitosan derivatives.

It is noteworthy that even at the end of 15 days of water deficit (lower water status), the plants that received the chitosan derivatives had greater leaf gas exchange (higher A and gs) and proline and sugars may facilitate this physiological stress response.

With respect to the effect of stimulating plant growth and development, in addition to modulating the expression of photosynthetic genes and redox homeostasis, chitosan can modulate carbohydrate metabolism31,57. For increased survival and growth of plants under stress, it is important to obtain energy and products from primary metabolism. Chitosan may increase the expression of the genes of enzymes involved in glycolysis31. The foliar application of the derivatives and chitosan yielded greater production of soluble sugars and starch, which are also inducers of carbon metabolism for tolerance to water stress. This higher amount of soluble sugars and starch could have been facilitated by the application of these biopolymers, as there was also greater photosynthesis with the application of these compounds.

Although the sprayed derivatives alone had an elicitor effect on the antioxidant system and on carbon metabolism, they did not result in production higher than that seen in the chitosan treatment. The treatment with biostimulants that was more relevant to the performance of the maize plant under water stress was the mixture of derivatives, as it resulted in a higher yield of grains. One of the reasons that may have led to a better yield from the mixture of the derivatives is the increase in the harvest index, which means a greater differential allocation of photoassimilates to the ear during the maize life cycle. Drought may lead to source and sink limitations, i.e., to decreased photosynthesis and/or ability to transport photoassimilates to the grains2,19. This difference in photoassimilate allocation and the photosynthetic rate between treatments shows that chitosan derivatives together may alleviate both source limitations and sink limitations, resulting in increased production.

The response of the plants to the mixture of derivatives suggests a synergistic effect when the two derivatives are applied together. The SUC and MCA derivatives have carboxylic acid groups that facilitate the solvation process in water and are therefore much more soluble in water than chitosan58. By leaving the two derivatives together in a mixture, they can form more ionized groups in the form of carboxylates, which would enhance their solubilization in the cellular medium and could explain their effects.

The higher effects of chitosan derivatives on oxidative stress responses were recorded mainly after application, i.e., at the beginning of the stress period but were also detected at the end of the stress period (15 days of stress). However, at the end of the stress period, although the spray treatments stand out in relation to the treatment without pulverization, the results are similar to those from pure chitosan. Thus, chitosan appears to act mainly at the end of the stress period, and the derivatives appear to act at the beginning and end of the stress period. This ensures protection for the plants during the whole stress period and can help explain the higher yield, especially in the mixture treatments. The mixture of derivatives resulted in a greater number of stress responses, which may be related to the increase in the enzymes SOD, CAT, GPX, GR, and PAL, and the increase in the content of phenolic compounds and proline. The greater stress response could also help explain the higher yield in the mixture treatments.

It is worth noting that the mixture of derivatives resulted in a significant/strong increase of glutathione reductase (GR) at the beginning of water stress. The mixture of derivatives increased the activity of an enzyme that has been shown to be essential in tolerance to abiotic stress, including drought59. GR is responsible for the regeneration of glutathione (GSH) using an electron donated by NADPH60. The GR in corn plants is present in three isoforms: one in the cytosol and two in the mitochondria and chloroplast61. As the chitosan oligomers can act as a signal in the chloroplastídeos31,33,36 where the highest GR activity is found (about 80% of the GR activity in photosynthetic tissues occurs by the chloroplast isoform)61,62, the oligomers of derived from chitosan that are formed in the form of a mixture could be potentializing the activity of this enzyme and contributing to the increase of grain yield. In addition, H2O2, which also increased in our work with the application of the mixture of derivatives at the beginning of stress, has been shown to be an ABA inducer that activates GR62. Several studies have shown the important role of GR in tolerance to water deficit in maize by reducing oxidative damages63,64,65.

The faster the plant stress signalling and the activation of the antioxidant defence begins, the less damage will be caused by a drought. Research on maize and sugarcane varieties with contrasting tolerances with spraying of salicylic acid also found an increase in antioxidant defence in the initial and final stages of the water deficit66,67. This does not occur with all biostimulants, which shows the particularity and importance of the studied derivatives. In sensitive maize, for example, abscisic acid did not lead to biochemical changes at the onset of stress20.

Conclusion

Under greenhouse conditions, the BRS 1030 hybrid under water deficit showed induced tolerance to the effects of water restriction and increased production attributes due to foliar application of a mixture of chitosan derivatives (N-succinyl and N, O- dicarboxymethylated). Such an induction of tolerance is due to the increase in photosynthesis and the activity of the antioxidant enzymes that minimize the oxidative effects caused by ROS. Chitosan and derivatives (applied separately) also induced the antioxidant defence system and increased the attributes of production but were inferior to the mixture of derivatives.

The higher activity of enzymes PAL and TAL also yielded a higher concentration of phenolic compounds in maize. The derivative application also resulted in greater foliar gas exchange and higher concentrations of osmoregulators, such as sugars and proline, which are important in preserving water status. All of these associated factors show that these molecules (N-succinyl and N, O-dicarboxymethyl) can minimize the cell damage caused by water deficit and improve the physiological and biochemical conditions of a stress-sensitive hybrid, making it more tolerant.

Methods

Synthesis of chitosan derivatives

The N-succinyl derivative was prepared according to Li and Ding68, with modifications. Chitosan (1 g) (Galena Química e Farmacêutica Ltda) was dissolved with magnetic stirring at room temperature in 100 mL of 1% (v/v) glacial acetic acid solution. Subsequently, a solution of succinic anhydride (1.8 g) in acetone (20 mL) was added dropwise under stirring. The mixture formed was subjected to ultrasonic irradiation of 40–50 Hz in a bath at 50 °C for 60 minutes. The resulting solution was then cooled to room temperature, hydrated ethyl alcohol (100 mL) was added, and the mixture was transferred to a freezer, where it remained for 24 hours. After this period, 1 mol L−1 aqueous sodium hydroxide solution was added until pH = 10. Subsequently, acetone was added until precipitation occurred as a whitish caseous mass. The mixture was again conditioned in a freezer for 48 hours. After this period, the product was filtered under vacuum using ethyl alcohol (approximately 1000 mL) to wash the retained solid, which was stirred with a glass stick throughout the cleaning process. The final product was obtained as an amorphous, coarse and yellowish-white solid after drying in a desiccator under vacuum and being protected from light. Using the same procedure, additional quantities of the product were obtained.

The N, O-dicarboxymethylated derivative was prepared according to the methodology proposed by Liu et al.69. Chitosan (5 g) was added to isopropyl alcohol (60 mL) under magnetic stirring at room temperature. An aqueous sodium hydroxide solution (12 mL) was then added at 10 mol L−1, divided into five portions, over a period of 25 minutes. The mixture was magnetically stirred for 30 minutes at room temperature. Subsequently, monochloroacetic acid (30 g) was added, divided into five portions over five minutes. The formed mixture was heated at 70 °C under magnetic stirring for 3 hours. The reaction mixture was then cooled, and the obtained solid product was vacuum-filtered and washed with absolute methanol (100 mL).

The product was rapidly oven-dried at 60 °C, which resulted in a yellow solid. Additional quantities of the product were obtained using the same procedure. The chitosan used to obtain the derivatives has a percentage of deacetylation (DDA%) of 63.5%17. The structures of the derivatives and chitosan are shown in Fig. 6.

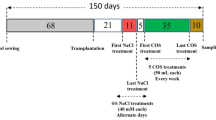

Plant material and growth conditions

A hybrid sensitive to water deficit (BRS 1030)18 from the Embrapa Breeding Programme was used. The experiment was conducted in a greenhouse located at Embrapa National Maize and Sorghum Research Centre in the city of Sete Lagoas, MG (732 m altitude, latitude 19°28′S, longitude 44°15′W). The average temperatures recorded during the evaluation period were as follows: maximum 36.3 °C, minimum 17.6 °C. Relative air humidity ranged from 72% to 40%.

The experiment was conducted in 20-L pots pre-filled with Typical Dystrophic Red Latosol. Fertilization was performed according to the soil chemical analysis recommendation, applying 10 g of 08-28-16 per 20 kg of soil at planting. Nitrogen side dressing was applied using 6 g of ammonium sulfate per pot at 30 and 60 days after planting. Three seeds were planted per pot, and after germination, thinning was performed, leaving two plants per pot. The plants were regularly irrigated, maintaining good soil moisture until water stress imposition.

Water stress imposition, application of chitosan and derivatives

The soil water potential was monitored daily in the morning and afternoon (9.00 a.m. and 3.00 p.m.), with the aid of a tensiometer (Watermark 200SS, Irrometer, California, USA), installed in the centre of the pots of each replicate at a depth of 20 cm. Water was replaced based on the readings obtained with the sensor and then returned to field capacity (FC) during the period that preceded the treatments. These calculations were performed with the aid of a spreadsheet made according to the water retention curve of the soil.

At the pre-flowering stage, two water treatments were imposed: irrigated (IR) and water deficit (WD). The first treatment consisted of daily irrigation until the soil reached a moisture close to field capacity (FC) (soil water tension of approximately −0.18 MPa), whereas in WD, irrigation was performed applying 50% of the total water available, that is, until the water tension in the soil reached −1.38 MPa, whose value corresponds to the soil specified.

The preparation of the solutions was made from the dilution of 0.5 mg of chitosan and its derivatives in 250 mL of water at a ratio of 0.5 mg/plant. Chitosan and its derivatives (SUC and MCA) and their mixture at the same ratio (MS) were applied using a costal sprayer with a flow rate of 120 Lha−1. Each plant was sprayed at a concentration of 0.5 mg plant−1 through a pressurized CO2 costal sprayer (2.15 kg f cm−2) equipped with an XR – Teejet 110.02 VS nozzle, spraying the equivalent of 120 L ha−1. This spraying occurred one day before water deficit imposition (55th day after planting) at the pre-flowering stage, and the application was made from outside the greenhouse to avoid receiving the product by other treatments. This procedure was standardized and timed as shown in the video (Supplementary Material, Video 1) simulating field application.

Gas exchange measurements

Gas exchange was measured on the 1st and 15th days of water stress imposition through a portable photosynthesis system (IRGA, LI-6400 XT, Li-Cor, Lincoln, Nebraska, USA). All measurements were taken in the morning, between 8.00 and 10.00 a.m. on a fully expanded leaf (spike leaf). The variables evaluated were photosynthetic rate (A) and stomatal conductance (gs). Measurements were taken in a leaf area of 6 cm2, with controlled CO2 flux at a concentration of 380 µmol CO2 mol−1 air. The photon flux density (PPFD) was 1500 µmol m−2 s−1 with a blue-red LED light source (6400-02B LED) and a controlled leaf temperature (30 °C)

Material collection for biochemical analysis

For biochemical analyses, the spike leaf was collected on the first and last day of water deficit imposition, submerged in liquid nitrogen and frozen at −80 °C.

Extraction and quantification of malonaldehyde (MDA) and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2)

Five hundred milligrams of plant material were macerated in liquid nitrogen; 2.5 mL of 0.1% trichloroacetic acid was added, and the material was centrifuged at 4,000 rpm for 30 minutes at 4 °C. Hydrogen peroxide was quantified according to the methodology proposed by Alixieva et al.70, and MDA (lipid peroxidation) was quantified according to Cakma and Horst71.

Extraction and quantification of antioxidant enzymes

For enzyme extraction, 500 mg of plant material macerated in liquid nitrogen was used. Extraction was carried out with 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.5. In the extraction solution, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM PMSF and 5% PVPP were added. The samples were centrifuged for 10 minutes at 14,000 rpm at 4 °C, and the supernatants were collected for quantification. The activity of the enzymes was expressed in milligrams (mg) of protein, which was determined by the Bradford method72.

The activity of superoxide dismutase (SOD, EC 1.15.1.1) was assessed by the ability to inhibit nitrotetrazolium blue (NBT) photoreduction; the activity of catalase (CAT, EC 1.11.1.6) was determined by the consumption of H2O2 at 240 nm for 3 minutes, with an extinction coefficient of 36 mM−1 cm−1. The activity of ascorbate peroxidase (APX, EC 1.11.1.11) was determined by monitoring the oxidation of ascorbate at 290 nm for 3 minutes, with an extinction coefficient of 2.8 mM−1 cm−1. The activity of guaiacol peroxidase (GPX, EC 1.11.1.7) was determined by the oxidation of guaiacol at 470 nm, with an extinction coefficient of 26.6 mM−1 cm−1. The activity of glutathione reductase (GR, EC 1.6.4.2) was determined by the oxidation of NADPH at 340 nm for 3 minutes, with an extinction coefficient of 6.2 mM−1 cm−1. All activities of these enzymes were measured according to the methodology proposed by Garcıa-Limones et al.73.

The activity of dehydroascorbate reductase (DHAR, EC 1.15.1.1) was determined by the reduction of DHA to ascorbic acid via GSH at 265 nm, with an extinction coefficient of 14 mM−1 cm−1, according to the methodology proposed by Hossain and Assada74.

Extraction and quantification of L-phenylalanine ammonia lyase (PAL EC 4.3.1.5), tyrosine ammonia lyase (TAL, EC 4.3.1) and phenolic compounds

For enzyme activity, 500-mg aliquots of frozen material were homogenized with 2 mL of 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer, pH 6.5. The material was centrifuged at 4 °C (14000 rpm, 20 minutes), and the supernatant was used as an enzyme extract. The activities were determined by the addition of 50 μL of the enzyme extract at 1 mL of the reaction medium (25 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.8 with 25 mM L-phenylalanine or 25 mM L-tyrosine). The reaction occurred for 1 hour at 37 °C and was quenched by the addition of 60 μL of 6 N HCl. The reaction products, trans-cinnamic (PAL) or p-coumaric (TAL) acid, were determined by reading the absorbance at 290 nm and 310 nm, respectively. The extraction and quantification followed the methodology proposed by Mehta and Bhavnarayana75.

For the extraction of phenolic compounds, 500 mg of plant material was macerated in liquid nitrogen, and 2 mL of methanol was added. The material was centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 30 minutes at a temperature of 20 °C. The supernatant was collected, and the procedure was repeated with the pellet. The samples were read at 720 nm. Quantification was performed by the Folin-Ciocalteau spectrophotometric method through a standard curve of gallic acid, according to the methodology proposed by Singleton et al.76.

Extraction and quantification of proline, total soluble sugars, total amino acids and starch

For the extraction of proline, 100 mg of plant material was macerated in liquid nitrogen with 10 mL of 3% sulfosalicylic acid. The solution was placed in tubes and shaken for 60 minutes. After separation of the material, the sample was filtered and analysed according to the methodology proposed by Bates et al.77.

For soluble sugars, amino acids and starch, 300 mg of plant material was macerated in liquid nitrogen. The extraction was carried out by the addition of the solution consisting of 3 mL methanol, 1,250 mL chloroform and 750 μL water. The samples were left overnight, and the next day, they were centrifuged for 30 minutes at 1300 rpm. The supernatant was collected for analysis of total sugars and amino acids. In the pellet, 1.5 mL of 30% perchloric acid was added.

The material was again left overnight, and the supernatant was collected for starch quantification. The quantification of total sugars and total amino acids was performed according to the methodology described by Gibon et al.78. Starch was quantified according to the methodology described by Fernie et al.79.

Production components

At the end of the experiment (harvesting), the weight of the ear, grain yield and harvest index [dry weight of the grain/(dry weight of the plant + dry weight of the grain)] * 100 were analysed.

Experimental design and data analysis

The experimental design was randomized block, with 6 treatments: irrigated (IR), water deficit (WD), water deficit with SUC application (WD + SUC), water deficit with the application of MCA (WD + MCA), water deficit with the application of MCA and SUC (WD + MS), and water deficit with the application of chitosan (WD + CHI), with 4 replicates, totalling 24 pots. All analyses were performed at two sampling times (1 and 15 days of water deficit), but the two sampling times were not statistically compared.

For the statistical analysis of the results, the analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Scott-Knott’s comparison test of averages at 0.05% significance (P ≤ 0.05) were run, using Sisvar software 4.3 (Universidade Federal de Lavras, Lavras, Brasil).

References

Filippou, P., Antoniou, C. & Fotopoulos, V. The nitric oxide donor sodium nitroprusside regulates polyamine and proline metabolism in leaves of Medicago truncatula. plants. Free Radical Bio. Med. 56, 172–183 (2013).

Souza, T. C. et al. Morphophysiology, morphoanatomy, and grain yield under field conditions for two maize hybrids with contrasting response to drought stress. Acta Physiol. Plant. 35, 3201–321 (2013).

Cunha, D. A., Coelho, A. B., Féres, J. G., Braga, M. J. & Souza, E. C. Irrigation as an adaptation strategy for small farmers to climate change: economic aspects. Rev. Econ. Sociol. Rural 51, 369–386, https://doi.org/10.1590/S0103-20032013000200009 (2013).

Porcel, R. et al. Arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis ameliorates the optimum quantum yield of photosystem II and reduces non-photochemical quenching in rice plants subjected to salt stress. J. Plant Physiol. 185, 75–83 (2015).

Choudhury, F. K., Rivero, R. M., Blumwald, E. & Mittler, R. Reactive oxygen species, abiotic stress and stress combination. Plant J. 90, 856–867 (2017).

Huang, S., Van Aken, O., Schwarzländer, M., Belt, K. & Millar, A. H. The roles of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species in cellular signaling and stress responses in plants. Plant Physiol. 171, 1551–1559 (2016).

Sharma, P., Jha, A. B., Dubey, R. S. & Pessarakli, M. Reactive oxygen species, oxidative damage, and antioxidative defense mechanism in plants under stressful conditions. J. Botany 2012, 26 (2012).

Lu, S., Zhuo, C., Wang, X. & Guo, Z. Nitrate reductase (NR)-dependent NO production mediates ABA- and H2O2-induced antioxidant enzymes. Plant Physiol. Bioch. 74, 9–15 (2014).

Pintó-Marijuan, M. & Munné-Bosch, S. Ecophysiology of invasive plants:osmotic adjustment and antioxidants. Trends Plant. Sci. 18, 660–666 (2013).

Xu, H., Lu, Y. & Zhu, X. Effects of Arbuscular Mycorrhiza on osmotic adjustment and photosynthetic physiology of maize seedlings in Black Soils region of Northeast China. Braz. Arch. Biol. Technol. 59, e16160392 (2016).

Ibrahim, E. A. & Ramadan, W. A. Effect of zinc foliar spray alone and combined with humic acid or/and chitosan on growth, nutrient elements content and yield of dry bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) plants sown at different dates. Sci. Hort. 184, 101–105 (2015).

Mármol, Z. et al. Chitin and Chitosan friendly polymer. A review of their applications. Rev. Tecnocientífica Uru. 1, 53–58 (2013).

Mondal, M. M. A., Puteh, A. B., Dafader, N. C., Rafii, M. Y. & Malek, M. A. Foliar application of chitosan improves growth and yield in maize. J. Food Agric. Environ. 11, 520–523 (2013).

Saharan, V. et al. Cu-Chitosan nanoparticle mediated sustainable approach to enhance seedling growth in maize by mobilizing reserved food. J. Agric. Food Chem. 64, 6148–6155 (2016).

Saharan,V. & Pal, A. Current and future prospects of chitosan-based nanomaterials in plant protection and growth, p.43–48. In Chitosan Based Nanomaterials in Plant Growth and Protection. Springer New Delhi (2016).

Takaki, M. Physicochemical study of the fungicidal activity of the amphiphilic derivatives of chitosan against fungi of the genus Aspergillus: interaction with membrane models. Dissertation, State University of São Paulo Julio de Mesquita Filho (2015).

Xu, T., Xin, M., Li, M., Huang, H. & Zhou, S. Synthesis, characteristic and antibacterial activity of N,N,N-trimethyl chitosan and its carboxymethyl derivatives. Carbohyd. Poly. 8, 931–936 (2010).

Martins, M. et al. Physicochemical characterization of chitosan and its effects on early growth, cell cycle and root anatomy of transgenic and non-transgenic maize hybrids. Aust. J. Crop Sci. 12, 56 (2018).

Souza, T. C. et al. The influence of ABA on water relation, photosynthesis parameters, and chlorophyll fluorescence under drought conditions in two maize hybrids with contrasting drought resistance. Acta Physiol. Plant. 35, 515–527 (2013).

Souza, T. C. et al. ABA application to maize hybrids contrasting for drought tolerance: changes in water parameters and in antioxidant enzyme activity. Plant Growth Regul. 73, 205–2017 (2014).

Anjum, S. A. et al. Cadmium toxicity in maize (Zea mays L.): consequences on antioxidative systems, reactive oxygen species and cadmium accumulation. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 22, 17022–17030 (2015).

Avramova, V. et al. High antioxidant activity facilitates maintenance of cell division in leaves of drought tolerant maize hybrids. Front Plant Sci. 8, 84 (2017).

Li, H. & Yu, T. Effect of chitosan on incidence of brown rot, quality and physiological attributes of postharvest peach fruit. J. Sci. Food and Agr. 81, 269–274 (2001).

Guan, Y. J., Hu, J., Wang, X. J. & Shao, C. X. Seed priming with chitosan improves maize germination and seedling growth in relation to physiological changes under low temperature stress. J. Zhejiang Univ-Sc. 10, 427–433 (2009).

Jiao, Z. et al. Effects of exogenous chitosan on physiological characteristics of potato seedlings under drought stress and rehydration. Potato Res. 55, 293–301 (2012).

Noman, A. et al. Foliar application of ascorbate enhances the physiological and biochemical attributes of maize (Zea mays L.) cultivars under drought stress. Arch. Agron. Soil. Sci. 61, 1659–1672 (2015).

Khan, W. M., Prithiviraj, B. & Smith, D. L. Effect of foliar application of chitin and chitosan oligosaccharides on photosynthesis of maize and soybean. Photosynthetica 40, 621–624 (2002).

Zhang, H. et al. Nitric oxide production and its functional link with OIPK in tobacco defense response elicited by chitooligosaccharide. Plant Cell Rep. 30, 1153–1162 (2011).

Dousseau, S. et al. Exogenous chitosan application on antioxidant systems of Jaborandi. Ciencia Rural 46, 191–197 (2016).

Bistgani, Z. E., Siadat, S. A., Bakhshandeh, A., Pirbalouti, A. G. & Hashemi, M. Interactive effects of drought stress and chitosan application on physiological characteristics and essential oil yield of Thymus daenensis Celak. The Crop J. 5, 407–415 (2017).

Chamnanmanoontham, N., Pongprayoon, W., Pichayangkura, R., Roytrakul, S. & Chadchawan, S. Chitosan enhances rice seedling growth via gene expression network between nucleus and chloroplast. Plant Growth Regul. 75, 101–114 (2015).

Choudhary, R. C. et al. Cu-chitosan nanoparticle boost defense responses and plant growth in maize (Zea mays L.). Sci. Rep. 7, 9754 (2017).

Hadwiger, L. A. Anatomy of a nonhost disease resistance response of pea to Fusarium solani: PR gene elicitation via DNase, chitosan and chromatin alterations. Front. Plant Sci. 6, 373 (2015).

Malerba, M. & Cerana, R. Chitosan effects on plant systems. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 17, 996 (2016).

Zeng, K., Deng, Y., Ming, J. & Deng, L. Induction of disease resistance and ROS metabolism in navel oranges by chitosan. Sci. Hortic-Amsterdam 126, 223–228 (2010).

Hadwiger, L. A. Multiple effects of chitosan on plant systems: Solid science or hype. Plant. Sci. 208, 42–49 (2013).

Pichyangkura, R. & Chadchawan, S. Biostimulant activity of chitosan in horticulture. Sci. Hortic-Amsterdam 196, 49–65 (2015).

Signini, S. & Campana-Filho, S. P. Characteristics and properties of purified chitosan in the neutral, acetate and hydrochloride forms. Polímeros 11, 58–64 (2001).

Prado, S. A. et al. Phenomics allows identification of genomic regions affecting maize stomatal conductance with conditional effects of water deficit and evaporative demand. Plant Cell Environ. 41, 314–326 (2017).

Pospisilova, J. Participation of phytohormones in the stomatal regulation of gas exchange during water stress. Biol. Plantarum 46, 491–506 (2003).

Iriti, M. et al. Chitosan antitranspirant activity is due to abscisic acid-dependent stomatal closure. Environ. Exp. Bot. 66, 493–500 (2009).

Lee, S. et al. Oligogalacturonic acid and chitosan reduce stomatal aperture by inducing the evolution of reactive oxygen species from guard cells of tomato and Commelina communis. Cell Biol. Signal Tr. 121, 147–152 (1999).

Khokon, A. R. et al. Chitosan induced stomatal closure accompanied by peroxidase-mediated Reactive Oxygen Species production in Arabidopsis. Biosci. Biotech. Bioch. 74, 2313–2315 (2010).

Pongprayoon, W., Roytrakul, S., Pichayangkura, R. & Chadchawan, S. The role of hydrogen peroxide in chitosan-induced resistance to osmotic stress in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Plant Growth Regul. 70, 159–173 (2013).

Hatfield, R. D. et al. Grass lignin acylation: p-coumaroyl transferase activity and cell wall characteristics of C3 and C4 grasses. Planta 229, 1253–1267 (2009).

Kuhn, O. J. Induction of resistance in common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris) by acibenzolar-S-methyl and Bacillus cereus: physiological, biochemical and growth and production parameters. Dissertation, University of São Paulo (2007).

Hura, T., Hura, K. & Grzesiak, S. Contents of total phenolics and ferulic acid, and PAL activity during water potential changes in leaves of maize single‐cross hybrids of different drought tolerance. J. Agron. Crop Sci. 194, 104–112 (2008).

Lavinsky, A. O., Magalhães, P. C., Ávila, G. A., Diniz, M. M. & Souza, T. C. Partitioning between primary and secondary metabolism of carbon allocated to roots in four maize genotypes under water deficit and its effects on productivity. Crop J. 3, 379–386 (2015).

Reddy, M. V. B., Arul, J., Angers, P. & Couture, L. Chitosan treatment of wheat seeds induces resistance to Fusarium graminearum and improves seed quality. J. Agric. Food. Chem. 47, 1208–1216 (1999).

Faoro, F., Maffi, D., Cantu, D. & Iriti, M. Chemical-induced resistance against powdery mildew in barley: the effects of chitosan and benzothiadiazole. Biocontrol 53, 387–401 (2008).

Katiyar, D., Hemantaranjan, A. & Singh, B. Chitosan as a promising natural compound to enhance potential physiological responses in plant: a review. Indian J. Plant Physi. 20, 1–9 (2015).

Gholizadeh, A. Effects of drought on the activity of Phenylalanine Ammonia Lyase in the leaves and roots of maize inbreds. Aust. J. Basic Appl. Sci. 5, 952–956 (2011).

Ahmad, N., Zuo, Y., Lu, X., Anwar, F. & Hameed, S. Characterization of free and conjugated phenolic compounds in fruits of selected wild plants. Food Chem. 190, 80–89 (2016).

Sousa, D. P. F. et al. Increased drought tolerance in maize plants induced by H2O2 is closely related to an enhanced enzymatic antioxidant system and higher soluble protein and organic solutes contents. Theor. Exp. Plant. Physiol. 28, 297–306 (2016).

Sun, C. X. et al. Metabolic response of maize plants to multi-factorial abiotic stresses. Plant Biol. 18, 120–129 (2016).

Li, Z. et al. Metabolic pathways regulated by chitosan contributing to drought resistance in white clover. J. Proteome Res. 16, 3039–3052 (2017).

Zhang, X., Li, K., Xing, R., Liu, S. & Li, P. Metabolite profiling of wheat seedlings induced by chitosan: revelation of the enhanced carbon and nitrogen metabolism. Front. Plant Sci. 8, 2017 (2017).

Reis, C. O. et al. Action of N-Succinyl and N,O-Dicarboxymethyl chitosan derivatives on chlorophyll photosynthesis and fluorescence in drought-sensitive maize. J. Plant Growth. Regul. 2018, 1–12 (2018).

Laxa, M. et al. The role of the plant antioxidant system in drought tolerance. Antioxidants 8, 94 (2019).

Hussain, S. et al. Oxidative stress and antioxidant defense in plants under drought conditions, p. 207–219. In: Hasanuzzaman, M., Hakeem, K., Nahar, K. & Alharby H. (eds) Plant Abiotic Stress Tolerance. Springer, Cham (2019).

Edwards, E. A., Rawsthorne, S. & Mullineaux, P. M. Subcellular distribution of multiple forms of glutathione reductase in leaves of pea (Pisum sativum L.). Planta 180, 278–284 (1990).

Harshavardhan, V. T., Wu, T. M. & Hong, C. Y. Glutathione Reductase and abiotic stress tolerance in plants, p. 265-286. In: Hossain, M. et al. (eds) Glutathione in Plant Growth, Development, and Stress Tolerance. Springer, Cham (2017).

Avramova, V. et al. High antioxidant activity facilitates maintenance of cell division in leaves of drought tolerant maize hybrids. Front. Plant Sci. 8, 84 (2017).

Nisar Ahmad, N., Malagoli, M., Wirtz, M. & Hell, R. Drought stress in maize causes differential acclimation responses of glutathione and sulfur metabolism in leaves and roots. BMC Plant Biol. 16, 247 (2016).

Anjum, S. A. et al. Effect of progressive drought stress on growth, leaf gas exchange, and antioxidant production in two maize cultivars. Environ Sci Pollut Res 23, 17132–17141 (2016).

Cia, M. C. et al. Antioxidant responses to water deficit by drought-tolerant and -sensitive sugarcane varieties. Ann. Appl. Biol. 161, 313–324 (2012).

Saruhan, N., Saglam, A. & Kadioglu, A. Salicylic acid pretreatment induces drought tolerance and delays leaf rolling by inducing antioxidant systems in maize genotypes. Acta Physiol. Plant. 34, 97–106 (2012).

Li, F. & Ding, C. Optimization of ultrasonic synthesis of N-succinyl-chitosan and adsorption of Zn2+ from aqueous solutions. Desalination and Water Treatment 52, 7856–7865 (2014).

Liu, X. F., Guan, Y. L., Yang, D. Z., Li, Z. & Yao, K. D. Antibacterial action of chitosan and carboxymethylated chitosan. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 79, 1324–1335 (2001).

Alexieva, V., Sergiev, I., Mapelli, S. & Karanov, E. The effect of drought and ultraviolet radiation on growth and stress markers in pea and wheat. Plant Cell Environ. 24, 1337–1344 (2001).

Cakmak, I. & Horst, W. J. Effect of aluminium on lipid peroxidation, superoxide ismutase, catalase, and peroxidase activities in root tips of soybean (Glycine max). Physiol. Plant. 83, 463–468 (1991).

Bradford, M. M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72, 248–254 (1976).

García-Limones, C., Hervá, A., Navas-Cortés, J. A., Jiménez-Diaz, R. M. & Tena, M. Induction of an antioxidant enzyme system and other oxidative stress markers associated with compatible and incompatible interactions between chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) and Fusarium oxysporum f. sp.ciceris. Physiol. Mol. Plant P. 61, 325–337 (2002).

Hossain, M. A. & Asada, K. Inactivation of ascorbate peroxidase in spinach chloroplasts on dark addition of hydrogen peroxide: its protection by ascorbate. Plant Cell Physiol. 25, 1285–1295 (1984).

Mehta, P. M. & Bhavnarayana, K. Role of phenylalanine and tyrosine ammonia lyase enzymes in the pigmentation during development of brinjal fruit. Pr. Plant Sci. 90, 293–297 (1981).

Singleton, V. L., Orthofer, R. & Lamuela-Raventós, R. M. Analysis of total phenols and other oxidation substrates and antioxidants by means of folin-ciocalteu reagent. Method. Enzymol. 299, 152–178 (1999).

Bates, L. S., Waldren, R. P. & Teare, I. D. Rapid determination of free proline for water stress studies. Plant Soil 39, 205–207 (1973).

Gibon, Y. et al. A robot-based platform to measure multiple enzyme activities in arabidopsis using a set of cycling assays: comparison of changes of enzyme activities and transcript levels during diurnal cycles and in prolonged darkness. Plant Cell 16, 3304–3325 (2004).

Fernie, A. R., Roscher, A., Ratcliffe, R. G. & Kruger, N. J. Fructose 2, 6-bisphosphate activates pyrophosphate: fructose-6-phosphate 1-phosphotransferase and increases triose phosphate to hexose phosphate cycling in heterotrophic cells. Planta 212, 250–263 (2001).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES), for the master’s scholarship (Finance Code 001); and Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de Minas Gerais (FAPEMIG) and Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq), for project financing (APQ-00651-14).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Paulo César Magalhães, Decio Karam: provided support during the assembly and conduction of the experiment, helped with data analysis and writing the manuscript. Letícia Aparecida Bressanin, Valquíria Mikaela Rabelo: helped in the implementation of the experiment and data collection. Diogo Teixeira Carvalho, Antônio Carlos Doriguetto, Marcelo Henrique dos Santos: responsible for synthesizing the biomolecules. Caroline Oliveira dos Reis: responsible for spraying the biomolecules. Plínio Rodrigues dos Santos Filho, Thiago Corrêa de Souza: oriented the research and the execution of the experiment; helped in writing the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rabêlo, V.M., Magalhães, P.C., Bressanin, L.A. et al. The foliar application of a mixture of semisynthetic chitosan derivatives induces tolerance to water deficit in maize, improving the antioxidant system and increasing photosynthesis and grain yield. Sci Rep 9, 8164 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-44649-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-44649-7

This article is cited by

-

Chitosan combined with humic applications during sensitive growth stages to drought improves nutritional status and water relations of sweet potato

Scientific Reports (2024)

-

Chitosan-GSNO nanoparticles: a positive modulator of drought stress tolerance in soybean

BMC Plant Biology (2023)

-

Solid–liquid extraction of bioactive compounds as a green alternative for developing novel biostimulant from Linum usitatissimum L.

Chemical and Biological Technologies in Agriculture (2023)

-

Protective effects of chitosan based salicylic acid nanocomposite (CS-SA NCs) in grape (Vitis vinifera cv. ‘Sultana’) under salinity stress

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Chitosan oligomers (COS) trigger a coordinated biochemical response of lemongrass (Cymbopogon flexuosus) plants to palliate salinity-induced oxidative stress

Scientific Reports (2023)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.