Abstract

Previous studies have found neural alterations in regions involved in cognitive and affective functions among Crohn’s disease (CD) patients. The present work recruited 18 CD patients and 18 age-gender matched healthy controls (HC) and specifically compared differences in resting-state functional connectivity (RSFC) within the executive control network (ECN) which has been implicated in cognitive function and default mode network (DMN), which has been implicated in affective function. Additionally, we examined the correlations between RSFC in ECN and verbal fluency (VF) in both groups as well as RSFC in DMN and anxiety level in the CD group. Results showed significantly increased RSFC between the right middle frontal gyrus and right inferior parietal lobule in ECN, as well as increased RSFC between the right precuneus and right posterior cingulate cortex in DMN, among CD patients compared to HC. However, the correlations between ECN/DMN and behavioral scores in each group were not significant, which was possibility due to the limited sample size. These findings suggest that CD patients may experience changes in the connectivity patterns in ECN and DMN. Increased connectivity observed on these networks could be a potential biomarker of a neuropsychiatric manifestation of CD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Crohn’s disease (CD), one of the main phenotypes of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), may affect any part of the gastrointestinal tract1, secretory gastrointestinal function and the immune system as well as increasing the intestinal permeability2. There is also evidence suggesting that the disease may affect the mental state by altering the motor, sensory systems causing psychological stress, precipitating mood disorders, and causing difficulties with concentration and thinking3. Compared to age-matched healthy controls, CD patients show brain changes in terms of altered cortical thickness in the bilateral superior and middle frontal gyri, areas (responsible for cognitive control and responding to behaviorally salient events), and the bilateral temporal poles and insular gyri, areas (involved in socio-emotional processing). These morphological changes may be the result of a confluence of factors such as the prolonged exposure to systemic inflammation, pain that may drive changes in the excitatory (e.g., NMDA-ergic) or inhibitory (e.g., GABA-ergic) systems as well as responses to various medications4, and could promote CD patients with a heightened sensitivity to their external environment and an inadequate ability to modulate their cognitive and emotional states4,5,6. Additionally, CD patients demonstrate decreased sub-cortical volumes, including the bilateral pallidum and right putamen which are associated with altered emotional and pain perception4. These volume changes suggest there is a neural basis to the alterations in CD patients’ cognitive and affective responses. Moreover, a functional neuroimaging study of a language or verbal fluency (VF) task which typically shows a left-lateralized hemispheric activation pattern in young healthy subjects, showed that the duration of CD significantly and positively correlated with verbal fluency task with the activation intensity in key homologous right hemisphere regions suggesting that the disease may lead to accelerated brain changes and compensatory activation patterns in these CD patients1.

To our knowledge, limited studies have examined the role of resting-state functional connectivity (RSFC) in CD patients. Liu et al. found disrupted local and global topological patterns of functional neural networks (i.e., subcortical, sensorimotor, cognitive control, and default-mode networks) as well as altered local topological patterns associated with clinical characteristics (i.e., anxiety) in CD patients7. The connectivity changes in the default mode network during remission period was examined by Thomann et al.8. However, cognitive neural substrates in CD have largely been unexplored in terms of resting-state functional connectivity. RSFC, the temporal dependency of neuronal activation patterns of anatomically separated brain regions, measures not only the level of co-activation of time-series between brain regions9 but also the low-frequency (~0.01–0.1 Hz) spontaneous neuronal activity in the brain10 and is believed to reflect neuronal function11,12,13,14. In the current study, we examined the RSFC patterns in CD patients and compared with age-gender matched healthy control (HC) participants. We focused on the networks involved in cognitive and affective function. Based on results from previous studies, we focused on the executive control network (ECN) and default mode network (DMN), both of which have functions of cognitive control, self-regulation, emotion regulation, and memory suppression15,16. The ECN, which includes the regions of the anterior cingulate cortex, anterior prefrontal cortex (aPFC), dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, ventrolateral prefrontal cortex (VLPFC), dorsomedial prefrontal cortex (dmPFC), inferior parietal cortex (IPC), and insula17,18, is a less studied network, which constitutes a novel approach to investigate the integrity of brain areas underlying executive function19. The DMN, which includes regions of the VLPFC, dmPFC, aPFC, posterior IPC, superior parietal cortex, occipital and temporal cortex19 with psychological functions such as attention and cognition15,20,21, is a widely studied network that activates in the absence of most external task demands15,22,23, but has rarely been examined in CD studies. We hypothesized that the ECN and DMN are impacted by CD and effects might be observable during periods of disease remission. We investigated differences in RSFC between CD patients and their healthy counterparts in these networks. Moreover, we also explored the correlations between ECN connectivity and VF task as well as DMN connectivity and anxiety level.

Results

Sample characteristics

The two groups did not significantly differ in education or VF score, as determined by a two-sample t-test and in distribution of gender and handedness, as determined by Fisher’s exact test as specified in Table 1. CD was specially measured by anxiety (BIS and BAS). The distribution of disease location of CD in our cohort was as follows: 55% ileocolonic CD, 25% isolated ileal involvement and 15% isolated colonic disease. Within the CD group, 15% of patients also had perianal disease, and 55% of them had non-structuring and non-penetrating CD.

RSFC findings

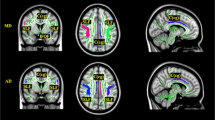

Based on a parametric independent two-sample t-test, significant group differences (FDR corrected p < 0.05) between CD and HC were observed within ECN as well as DMN. Within the ECN, RSFC associated with the increased network between the right middle frontal gyrus and right inferior parietal lobule in CD than HC (see Fig. 1a and Table 2). Within the DMN, RSFC associated with the increased network between the right precuneus and right posterior cingulate cortex in CD than HC (see Fig. 1b and Table 2). Thus, in both networks the patients group showed elevated RSFC relative to the control group as exemplified in Fig. 2.

RSFC-behavior relationship

Within both the ECN and DMN that were identified using t-test, the findings from correlation analysis with all behavioral performances did not reach significance, most likely due to the limited sample size.

Discussion

Limited studies have evaluated RSFC in the CD population7,8. Our study provides an addition to this literature and suggests that CD can alter the functional connectivity of the brain. As hypothesized, the ECN and DMN appear to be affected by CD and provides further evidence for gut-brain communication. CD patients exhibited higher levels of RSFC in comparison to HC. Increased RSFC have also been reported in several neuropsychiatric disorders including depression, as well as in people with chronic pain24. Our findings are in support of the growing number of studies4,6,25,26 that use neuroimaging to examine the neural substrates impacted by CD. MRI, in particular, is a radiation and task-free modality and could complement the standard diagnostic tools for CD such as ileocolonoscopy and gastroduodenoscopy to study the full extent of the impact of CD and potentially better manage its non-gastrointestinal effects27.

Our study found alterations in RSFC associated with the right middle frontal gyrus and right inferior parietal lobule in the ECN of CD compared to HC. Specifically, frontal connectivity with the inferior parietal lobule could reflect the functions of top-down control28 or spatial attention29,30. Although the results of correlations were not significant, the decreased RSFC between frontal connectivity with inferior parietal lobule in HC possibly showed their better performance on VF task. This correspondence is supported by the known involvement of the inferior parietal lobule in attentional control31. On the other hand, CD patients exhibited a deviation from this trend with increased frontal RSFC being associated with poorer performance on VF. This deviation may be due to increased levels of inhibitory control by CD patients which may be required to suppress incorrect or irrelevant responses during the VF task32.

We also observed increased RSFC involving the right precuneus and right posterior cingulate cortex (both of which belong to a predominantly posterior DMN subsystem8) in the CD group compared to HC. Increased RSFC within the posterior DMN was also demonstrated in a recent CD study by Thomann et al. who found the association between altered RSFC in DMN and various mental disorders including depression and anxiety disorders8. More significant changes in these two regions in CD patients compared to HC as measured by fMRI-based ReHo after undergoing electropuncture treatment has been demonstrated by Bao and colleagues33. While our findings from the correlation analysis were not significant, there could be other potential confounders that potentially affect anxiety performances in CD group and it needs further investigation.

This study was limited by a modest sample size. Increasing the sample size would be particularly important to power the correlation analyses for identification of neural correlates linked with behavioral outcomes associated with CD. Our study was based on five-minute long fMRI scans which is considered to be reasonable acquisition time in order to find reliable intrinsic network connectivity34,35. However, test-retest reliability studies have also indicated that strength of connectivity can be significantly enhanced with longer acquisition times36. This factor, coupled with the sample size may have contributed to limited significant effects in this cohort. Future neuroimaging-based investigations of CD should take this into consideration during the study design. While we controlled for age, gender, handedness and education, there could be other potential confounders that were not included in this analysis. Furthermore, we investigated the ECN and DMN only and thus cannot draw inferences about the effect of CD on other brain networks. Further investigation is needed to assess the impact of cognitive capacity, medications, CD duration, and prior severity of CD on RFSC and to better understand the relationship between RSFC and clinical/behavioral measures as well as RSFC changes over time. While we only focused on the functional connectivity effects occurring in the CD population, a complete characterization would require examination of complementary information from MR such as white matter, grey matter volumes, and potential lesion burden.

This study highlights the utility of resting-state fMRI as a complementary tool to assess the neural manifestations associated with CD. Our results suggest that CD patients in remission exhibit alterations in the connectivity patterns in the ECN and DMN compared to age-gender matched HC. Increased levels of connectivity in CD compared to the HC could serve as potential biomarker for the neuropsychiatric manifestation of CD.

Methods

Participants

Nineteen CD patients and nineteen gender- and age-matched healthy controls (HC) were recruited for this study. Because one CD and HC participant each were removed from analysis due to high levels of head motion, we excluded these two participants (so effectively there were eighteen CD patients and eighteen HCs). All participants were recruited on a voluntary basis and provided informed and written consent for participation. Participants were included in the study if they were at least 18 years or older. CD was diagnosed based on endoscopy, histology or radiographic imaging. Participants with CD were in remission based on a Harvey Bradshaw Index37,38 score of less than five. Criteria for exclusion were: pregnancy, co-morbid pain disorders unrelated to IBD, scheduled medications for treatment of pain, and contraindications to MRI. A 0–10 rating scale39,40,41,42 was used to record the intensity of any pain experienced within a week leading up to the study visit in CD patients. The Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CES-D; 20 items) scale43,44 was utilized to evaluate symptoms associated with depression. Table 1 shows participants’ basic demographic information.

All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. All experimental protocols were approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the School of Medicine and Public Health, University of Wisconsin-Madison. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

MRI data acquisition

Five minutes each of resting-state functional MRI and T1 structural MRI data were collected on a 3T MRI scanner (GE750, GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI). The acquisition parameters were as follows: TR/TE/θ = 2600 ms/22 ms/60°, FOV = 100 × 100 mm, in-plane resolution = 3.5 × 3.5 mm2, slice thickness = 3.5mm. Anatomical MRI data were acquired using a T1-weighted, three-dimensional, gradient-echo pulse-sequence (MPRAGE) with TR/TE/θ = 8160 ms/3.18 ms/12°, FOV = 100 × 100 mm, in-plane resolution = 1 × 1 mm2, slice thickness = 1 mm. During the scanning, participants laid supine on the scanner bed. Foam pads were used to minimize head motion. Participants were instructed to close their eyes, keep their heads still, and to relax. All participants reported having their eyes closed and being awake during the scan.

Behavioral data acquisition

To assess the behavioral aspects associated with CD, we acquired measures of verbal fluency (VF) and anxiety to study the neural correlates within ECN and DMN respectively.

Verbal Fluency

Controlled Oral Word Association Test (COWAT) was administered to measure verbal fluency (VF)45. Participants were required to produce words beginning with the letters “F,” “A,” “S,” in three respective 1-minute trials. The total number of correct responses over the three letters was used to quantify VF. Normalized VF scores achieved on the task were used in subsequent analyses by accounting for age and education levels.

Anxiety

Behavioral inhibition system and behavioral approach system (BIS/BAS) scales were administered by questionniare to measure anxiety46,47. BIS and BAS scores were calculated for each participant and included 24 items 4-point Likert scale for 20 score-items and 4 fillers). Total scores for BIS (range = 7–28; 7 items) and BAS (range = 13–52; 13 items) were used as outcomes measures of anxiety. While a mean BAS score was computed encompassing domains of reward responsiveness, fun-seeking, and drive, a total BIS score was recorded in response to adverse events.

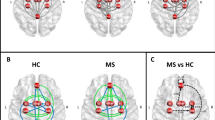

Region of interest (ROI) selection

Based on a prior study on functional organization of the brain48, ROIs in two large-scale brain networks were utilized: (1) 39 ROIs in ECN consisted of 14 ROIs from the cingular-opercular (CO) network and also 25 ROIs from the frontoparietal (FP) network as illustrated in Fig. 3 and Table 3, and (2) 58 ROIs in DMN as shown in Fig. 4 and Table 4. Spherical ROIs, each of radius 5 mm, were created as per the standard MNI coordinates provided by the template.

Data preprocessing

The RSFC analysis was performed using the Data Processing Assistant for Resting-state fMRI Basic Edition toolbox (DPARSF V4.3), which is part of the Data Processing and Analysis of Brain Imaging (DPABI) toolbox version 3.1 (http://rfmri.org/dpabi)49,50. DPARSF is a convenient plug-in software based on Statistical Parametric Mapping (SPM) and Resting-State fMRI Data Analysis Toolkit (REST) (http://www.restfmri.net) integrated in Matlab50. The Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine (DICOM) files were first arranged and the parameters (such as time points, TR, slice number, voxel size et al.) were then set. DPARSF then produced the preprocessed data (with slice timing, realignment, normalization, and smoothing). The first five volumes were discarded to allow the magnetization to approach a dynamic equilibrium, and for the participants to get used to the scanner noise. Data pre-processing, including slice timing, realignment, normalization, smoothing, regressing out head motion parameters (scrubbing within Friston 24-parameter model regression; bad time points were identified using a threshold of frame-wise displacement (Power FD) > 0.2 mm as well as 1 volume before and 2 volumes after at the individual-subject level as well as accounting for head motion at the group-level (i.e., covariate analysis))49,51,52, and spatial normalization to the Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) template (resampling voxel size of 3.5 × 3.5 × 3.5 mm), were conducted using SPM8 and DPARSF version 4.350,53. A spatial Gaussian filter of 4 mm FWHM (full-width at half maximum) was used for smoothing. We calculated the temporal correlations as spontaneous neuronal connectivity to quantify RSFC and generated a 39 × 39 symmetric correlation matrix for ECN and a 58 × 58 symmetric correlation matrix for DMN per participant for CD and HC groups. From these matrices, a total of 741 and 1653 unique pairwise functional connections were extracted from the ECN and DMN, respectively, for each participant.

Statistical analysis

Group differences between RSFC of CD and HC groups were examined using independent two-sample t-test in IBM SPSS version 23, with head motion used as a covariate. All results were corrected for multiple comparisons by estimating the false discovery rate (FDR)54 based on the procedure in Matlab R2016b (The MathWorks, Inc., Natick, Massachusetts, United States). Specific functional connections with corrected p-value < 0.05 were deemed to be significantly different between CD and HC groups in each network. Additionally, exploratory analyses were performed by correlating the identified RSFC connections from t-tests: (1) in ECN with performance on VF task in CD and HC groups, and (2) in DMN with anxiety measures in CD group only. Significant brain connections identified by the t-test were used to perform correlation analyses based on Pearson’s correlation using IBM SPSS version 23. The group differences were visualized with the BrainNet Viewer Toolbox55.

References

Beniwal-Patel, P. et al. Altered brain functional activation and connectivity patterns in patients with crohn’s disease in remission. Gastroenterology 150(4), S392 (2016).

Sajadinejad, M., Asgari, K., Molavi, H., Kalantari, M. & Adibi, P. Psychological issues in inflammatory bowel disease: an overview. Gastroenterology Research and Practice 3, 106502 (2012).

Langenberg, D. R., Yelland, G. W., Robinson, S. & Gibson, P. R. Cognitive impairment in Crohn’s disease is associated with systemic inflammation, symptom burden and sleep disturbance. United European Gastroenterology Journal 5(4), 579–587 (2017).

Nair, V. et al. Structural imaging changes and behavioral correlates in patients with Crohn’s Disease in remission. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 10, 460 (2016).

Bushnell, M. C., Ceko, M. & Low, L. A. Cognitive and emotional control of pain and its disruption in chronic pain. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 14, 502–511 (2013).

Thomann, A. K. et al. Altered markers of brain development in Crohn’s Disease with extraintestinal manifestations–a pilot study. PloS one 11(9), e0163202 (2016).

Liu, P. et al. Altered topological patterns of brain functional networks in Crohn’s disease. Brain imaging and behavior 3, 1–13 (2018).

Thomann, A. K. et al. Intrinsic neural network dysfunction in quiescent Crohn’s Disease. Scientific Reports 7(1), 11579 (2017).

van den Heuvel, M. P. & Hulshoff, H. E. Exploring the brain network: a review on resting-state fMRI functional connectivity. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 20(8), 519–534 (2010).

Lv, Y. T. et al. Correlations in spontaneous activity and gray matter density between left and right sensoritmotor areas of pianists. Neuroreport 19, 631–634 (2008).

Damoiseaux, J. S. et al. Consistent resting-state networks across healthy subjects. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 103, 13848–12853 (2006).

Fox, M. D. & Raichle, M. E. Spontaneous fluctuations in brain activity observed with functional magnetic resonance imaging. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 8, 700–711 (2007).

Hou, J., Chen, C. & Dong, Q. Resting-state functional connectivity and pitch identification ability in non-musicians. Frontiers in Neuroscience 9, 7 (2015).

Zhang, M. et al. Resting-state functional connectivity and reading abilities in first and second languages. NeuroImage 84, 546–553 (2014).

Beaty, R. E., Benedek, M., Kaufman, S. B. & Silvia, P. J. Default and executive network coupling supports creative idea production. Scientific Reports 5, 10964 (2015).

Spreng, R. N. et al. Goal-congruent default network activity facilitates cognitive control. The Journal of Neuroscience 34(42), 14108–14114 (2014).

Seeley, W. W. et al. Dissociable intrinsic connectivity networks for salience processing and executive control. The Journal of Neuroscience 27, 2349–2356 (2007).

Vincent, J. L., Kahn, I., Snyder, A. Z., Raichle, M. E. & Buckner, R. L. Evidence for a frontoparietal control system revealed by intrinsic functional connectivity. Journal of Neurophysiology 100, 3328–3342 (2008).

Wu, L. et al. Resting state executive control network adaptations in amnestic mild cognitive impairment. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease 40(4), 993–1004 (2014).

Andrews-Hanna, J. R. The brain’s default network and its adaptive role in internal mentation. Neuroscientist 18, 251–270 (2012).

Andrews-Hanna, J. R., Smallwood, J. & Spreng, R. N. The default network and self-generated thought: component processes, dynamic control, and clinical relevance. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1316, 29–52 (2014).

Gusnard, D. A. & Raichle, M. E. Searching for a baseline: Functional imaging and the resting human brain. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 2, 685–694 (2001).

Shulman, G. L. et al. Common blood flow changes across visual tasks: II. Decreases in cerebral cortex. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience 9, 648–663 (1997).

Greicius, M. Resting-state functional connectivity in neuropsychiatric disorders. Current Opinion in Neurology 21(4), 424–430 (2008).

Bao, C. et al. Differences in brain gray matter volume in patients with Crohn’s disease with and without abdominal pain. Oncotarget 8(55), 93624 (2017).

Chen, M., Lee, G., Kwong, L. N., Lamont, S. & Chaves, C. Cerebral white matter lesions in patients with Crohn’s disease. Journal of Neuroimaging 22(1), 38–41 (2012).

Yoon, K., Chang, K. T. & Lee, H. J. MRI for Crohn’s disease: present and future. BioMed research international 786802, 1–9 (2015).

Ciaramelli, E., Grady, C. L. & Moscovitch, M. Top-down and bottom-up attention to memory: a hypothesis (AtoM) on the role of the posterior parietal cortex in memory retrieval. Neuropsychologia 46, 1828–1851 (2008).

Corbetta, M. & Shulman, G. L. Control of goal-directed and stimulus-driven attention in the brain. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 3, 201–215 (2002).

Egner, T. et al. Neural integration of top-down spatial and feature-based information in visual search. The Journal of Neuroscience 28, 6141–6151 (2008).

Hopfinger, J. B., Buonocore, M. H. & Mangun, G. R. The neural mechanisms of top-down attentional control. Nature neuroscience 3(3), 284 (2000).

Hirshorn, E. A. & Thompson-Schill, S. L. Role of the left inferior frontal gyrus in covert word retrieval: neural correlates of switching during verbal fluency. Neuropsychologia 44(12), 2547–2557 (2006).

Bao, C. et al. Different brain responses to electro-acupuncture and moxibustion treatment in patients with Crohn’s disease. Scientific Reports 6, 36636 (2016).

Fox, M. D. et al. The human brain is intrinsically organized into dynamic, anticorrelated functional networks. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 102(27), 9673–9678 (2005).

Van Dijk, K. R. et al. Intrinsic functional connectivity as a tool for human connectomics: Theory, properties, and optimization. Journal of Neurophysiology 103(1), 297–321 (2009).

Birn, R. M. et al. The effect of scan length on the reliability of resting-state fMRI connectivity estimates. NeuroImage 83, 550–558 (2013).

Harvey, R. F. & Bradshaw, J. M. A simple index of Crohn’s-disease activity. Lancet 315, 514 (1980).

Zittan, E., Kabakchiev, B. & Kelly, O. B. Development of the Harvey-Bradshaw Index-pro (HBI-PRO) score to assess endoscopic disease activity in Crohn’s Disease. Journal of Crohn’s and Colitis 11(5), 543–548 (2017).

Bijur, P. E., Silver, W. & Gallagher, E. J. Reliability of the visual analog scale for measurement of acute pain. Academic Emergency Medicine 8, 1153–1157 (2001).

Gallagher, E. J., Liebman, M. & Bijur, P. E. Prospective validation of clinically important changes in pain severity measured on a visual analog scale. Annals of Emergency Medicine 38, 633–638 (2001).

Gallagher, E. J., Bijur, P. E., Latimer, C. & Silver, W. Reliability and validity of a visual analog scale for acute abdominal pain in the ED. Annals of Emergency Medicine 20, 287–290 (2002).

Huskisson, E. C. Measurement of pain. Lancet 304, 1127–1131 (1974).

Devins, G. et al. Measuring depressive symptoms in illness populations: psychometric properties of the center for epidemiologic studies depression (CES-D) scale. Psychology & Health 2(2), 139–156 (1988).

Sheehan, T. J., Fifield, J., Reisine, S. & Tennen, H. The measurement structure of the center for epidemiologic studies depression scale. Journal of Personality Assessment 64, 507–521 (1995).

Benton, A., Hamsher, K. & Sivan, A. Multilingual aphasia examination. (Iowa City, IA, 1976).

Carver, C. S. & White, T. L. Behavioral-inhibition, behavioral activation, and affective responses to impending reward and punishment–the Bis/Bas scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 67, 319–333 (1994).

Gray, J. A. & McNaughton, N. The neuropsychology of anxiety: an enquiry into the functions of the septo-hippocampal system (2nd ed.) (Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2000).

Power, J. et al. Functional network organization of the human brain. Neuron 72(4), 665–678 (2011).

Yan, C. G., Wang, X. D., Zuo, X. N. & Zang, Y. F. DPABI: Data Processing & Analysis for (Resting-State) Brain Imaging. Neuroinformatics 14, 339–351 (2016).

Yan, C. & Zang, Y. DPARSF: A MATLAB toolbox for pipeline data analysis of resting-state fMRI. Frontiers in Systems Neuroscience 4, 13 (2010).

Yan, C. G., Craddock, R. C., He, Y. & Milham, M. P. Addressing head motion dependencies for small-world topologies in functional connectomics. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 7, 910 (2013).

Power, J. D., Barnes, K. A., Snyder, A. Z., Schlaggar, B. L. & Petersen, S. E. Spurious but systematic correlations in functional connectivity MRI networks arise from subject motion. Neuroimage 59, 2142–2154 (2012).

Kuhn, S., Vanderhasselt, M. A., De Raedt, R. & Gallinat, J. Why ruminators won’t stop: the structural and resting state correlates of rumination and its relation to depression. Journal of Affective Disorders 141, 352–360 (2012).

Benjamini, Y. & Hochberg, Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society 57, 289–300 (1995).

Xia, M., Wang, J. & He, Y. BrainNet Viewer: a network visualization tool for human brain connectomics. PloS one 8(7), e68910 (2013).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the study participants and their families for their involvement in the study and coordinators JV and JS for their help with patient recruitment and data collection, and the MR staff of the Wisconsin Institutes for Medical Research (WIMR) center. This work was supported by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (grant number K12HD055894 to SS), and pilot funding from the UW-Madison Department of Radiology R&D (to SS) and the UW-Madison Department of Medicine (to SS), by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (grant number K23NS086852 to VP), American Heart Association (AHA) 2015 Innovation and AHA 2015 Midwest Affiliate Grant-in-Aid award (VP), by the National Institute of Health (grant numbers T32GM008692, UL1TR000427, T32EB011434). The content of this paper is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.H. analyzed dataset, wrote paper, made revisions. R.M. analyzed dataset (brain network and correlation), wrote some method, results, and discussion sections, made revisions. V.A. designed overall research collected dataset, made revisions to this paper. K.D. made revisions. P.B.P. designed research and helped collect dataset. S.S. and V.P. designed research, applied funding, made revisions to this paper. All the authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

Dr. Saha is a consultant for UCB Biosciences, Inc. All the other authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. All authors further declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any non-financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hou, J., Mohanty, R., Nair, V.A. et al. Alterations in resting-state functional connectivity in patients with Crohn’s disease in remission. Sci Rep 9, 7412 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-43878-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-43878-0

This article is cited by

-

Aberrant intrinsic functional brain networks in patients with functional constipation

Neuroradiology (2023)

-

Altered functional brain networks in coronary heart disease: independent component analysis and graph theoretical analysis

Brain Structure and Function (2023)

-

Supraspinal Mechanisms of Intestinal Hypersensitivity

Cellular and Molecular Neurobiology (2022)

-

Alterations in brain white matter microstructural properties in patients with Crohn’s disease in remission

Scientific Reports (2020)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.