Abstract

In this work, the design, microstructures and mechanical properties of five novel non-equiatomic lightweight medium entropy alloys were studied. The manufactured alloys were based on the Al65Cu5Mg5Si15Zn5X5 and Al70Cu5Mg5Si10Zn5X5 systems. The formation and presence of phases and microstructures were studied by introducing Fe, Ni, Cr, Mn and Zr. The feasibility of CALPHAD method for the design of new alloys was studied, demonstrating to be a good approach in the design of medium entropy alloys, due to accurate prediction of the phases, which were validated via X-ray diffraction and scanning electron microscopy with energy dispersive spectroscopy. In addition, the alloys were manufactured using an industrial-scale die-casting process to make the alloys viable as engineering materials. In terms of mechanical properties, the alloys exhibited moderate plastic deformation and very high compressive strength up to 644 MPa. Finally, the reported microhardness value was in the range of 200 HV0.1 to 264 HV0.1, which was two to three times higher than those of commercial Al alloys.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Traditional alloys are based on a main element with additional elements alloyed to obtain the properties required for a specific industrial application. Therefore, a knowledge of alloys near the corners of a multicomponent phase diagram is well developed, with much less knowledge of alloys at the centre of the phase diagram1. The traditional alloy strategy has been very restrictive in exploring the full range of possible alloys, because there are many more compositions at the centre of a multicomponent phase diagram than at the corners.

To overcome the above concerns, High Entropy Alloys (HEAs) and equiatomic multicomponent alloys were proposed respectively by Yeh et al.2 and Cantor et al.3 in 2004. Unlike traditional alloys, HEAs or equiatomic multicomponent alloys were composed of five or more metallic elements in equimolar or near-equimolar ratios. The basic principle behind the new alloy strategy was to promote the formation of solid solution phases, avoiding the formation of brittle intermetallic compounds (ICs).

Yeh et al. proposed a classification of the alloys in function of the configurational entropy (ΔSconf). The alloys were classified as HEAs when their ΔSconf at a random state was higher than 1.5 R (R being the gas constant), regardless of whether they are single-phase or multiphase at room temperature (RT). Alloys were classified as Medium Entropy Alloys (MEAs), when the values of their ΔSconf were in the range from 1R to 1.5 R. Finally, some commercial alloys such as 7075 aluminium alloys or AZ91D were classified as low entropy alloys, its ΔSconf is less than 1R4. Although, the initial publications focused on single-phase HEAs because of their excellent properties5, some multiphase and non-equiatomic HEAs also demonstrated to possess excellent mechanical and physical properties6,7,8. Thus, the term Complex Concentrated Alloys (CCAs) was introduced for multiphase HEAs. For the sake of simplicity during the present work, the term HEAs is used for single phase SS when ΔSconf ≥ 1.5 R. The term CCAs is used for multiphase alloys when ΔSconf ≥ 1.5 R. Finally, alloys are named MEAs when 1R ≤ ΔSconf ≤ 1.5 R.

The most commonly used melting techniques to manufacture HEAs, MEAs and CCAs are vacuum arc melting and vacuum induction melting9. These techniques are basically based on melting in a protective atmosphere and casting in a water refrigerated copper mould. Multiple repetitive melting and solidification are often performed to guarantee the chemical homogeneity of the alloys. The principles of manufacturing HEAs were studied by Kumar et al.10 and Jablonski et al.11. Despite the expensive casting process, HEAs and most CCAs usually possess poor liquidity and castability, and considerable compositional inhomogeneity. The reason is that they contain multiple elements with high concentrations. In addition, the melting point of some elements (Cr, Fe, Ti…) can be higher than the boiling point of other alloying elements like Mg, Li or Zn, which can lead to evaporation losses and casting defects. Thus, the industrial scale manufacturing of HEAs, MEAs and CCAs has become a new challenge due to the high complexity of the process.

Inspired by HEAs, Raabe et al. developed novel steels based on high ΔSconf for stabilizing a single-phase SS matrix12. The ΔSconf of these alloys are between 1R and 1.5 R, which means that they can be classified as MEAs. They studied several alloys based on the Fe-Mn-Al-Si-C and Fe-Mn-Al-C systems with a Fe concentration between 41–70 at.%. The mechanical properties of the studied alloys were superior compared to those of many conventional austenitic steels. Subsequently, numerous works have been carried out based on MEAs with Fe as main element13,14,15,16,17,18. A similar design strategy was employed by Laws et al., creating a range of high entropy brasses and bronzes. The Cu-Mn-Ni ternary system with the addition of Al, Sn and Zn was explored. These alloys showed high compressive strength, ductility and hardness in comparison with standard commercial brasses19.

A great deal of research has been conducted on the development of MEAs with exceptional mechanical properties20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28, but few experiments have been carried out to discover novel lightweight MEAs (LWMEAs). Instead, excellent mechanical properties were often obtained on compression and hardness tests for studied LWMEAs. Mg46(MnAlZnCu)54 and Mg50(MnAlZnCu)50 alloys exhibited moderate hardness (178 HV-226 HV) and high compression strength (400 MPa–482 MPa) at RT, but they exhibited a brittle behaviour29. Equimolar MgMnAlZnCu alloy was also studied, which has similar mechanical properties but a higher density30. The Al-Li-Mg-Zn-Cu and Al-Li-Mg-Zn-Sn high and medium entropy systems were studied by Yang et al.31. All the alloys exhibited high strength, and the plastic strain of Al80Li5Mg5Zn5Sn5 and Al80Li5Mg5Zn5Cu5 MEAs reached up to 17 and 16% respectively. On the other hand, AlLiMgZnSn and AlLi0.5MgZn0.5Sn0.2 alloys exhibited very brittle behaviour, with plastic strain values below 1,2%. In another related study, Beak et al. reported the microstructure and compressive properties of Al70Mg10Si10Cu5Zn5 alloy at RT and 350 °C. An ultrasonic melt treatment was used to improve the ultimate compressive strength of as-cast alloy from 573 to 681 MPa32. The precipitation behaviour and the mechanical properties of Al-6Mg-9Si-10Cu-10Zn-3Ni (wt.%) alloy was investigated by Ahn et al.33,34. The Al-6Mg-9Si-10Cu-10Zn-3Ni alloy showed excellent mechanical properties when compared to some of the commercial Al alloys. Recently, a series of lightweight Al–Mg system entropic alloys containing Zn, Cu, and Si were studied by Shao et al.35. The fabricated alloys had high strength, with compressive strength exceeding 500 MPa at RT.

Recently, a new route to design non-equiatomic MEAs that contains one matrix element and several alloying elements was proposed. The range of matrix composition can be up to 66 at.%, 71 at.% and 73 at.% for quaternary, quinary and senary systems, respectively36. This simplified the complex design, manufacture and physical metallurgy of HEAs and most CCAs. In addition, MEAs also have the advantage of benefiting from the “four core effect” proposed for HEAs37. Despite the physical metallurgy and composition of MEAs is not as complex as HEAs or CCAs, the design of MEAs is still a challenge. To date, CALPHAD method has demonstrated to be the most reliable method for the study and the design of HEAs and CCAs38,39,40. However, further work is still needed on the design of MEAs to make them viable as engineering materials.

Motivated by the above concerns, and because of the great potential that LWMEAs offer for widespread applications, the design, microstructures and mechanical properties of five novel non-equiatomic MEAs based on the Al65Cu5Mg5Si15Zn5X5 and Al70Cu5Mg5Si10Zn5Y5 (X = Fe, Ni and Y = Cr, Mn, Zr, in at.%) systems were studied. The alloys were designed following the application-based redesign strategy41. They were designed in a framework of five elements and a variable high melting point transition metal was added to each alloy. The elements were selected on the basis that Al-Si alloys are the most common casting alloys in the automotive industry. The major alloying elements used in Al-Si alloys are Cu, Mg, Ni and Zn, as their addition improve the mechanical and physical properties of the alloys42. It should be noted that the use of expensive or scarce elements was avoided, and that they were fabricated by an industrial scale die casting process. They were designed by Thermo-Calc to achieve a ductile α-Al matrix reinforced with different ICs to overcome the weaknesses (the decrease of their mechanical properties at high temperatures, poor wear behaviour and low strength and hardness) of commercial Al alloys.

Results

Design of medium entropy alloys

Following the previously mentioned new route to design non-equiatomic MEAs, the range of matrix composition was defined between 65 at.% and 70 at.%. Thus, from above mentioned classification based on the ranges of ∆Sconf, alloys can be divided in low, medium and high entropy alloys. According to Boltzmann’s hypothesis, for a n-element multicomponent alloy at a random state, ΔSconf can be calculated by the following equation:

where R is the constant of gases (8,314 J. (mol.K)−1), Xi is the fraction of atom of element “i” and “n” is the total number of elements. Based on Eq. (1), the values of ΔSconf were 1,2 R J.mol/K for Al65Cu5Fe5Mg5Si15Zn5 and Al65Cu5Mg5Ni5Si15Zn5 and 1,1 R J.mol/K for Al70Cr5Cu5Mg5Si10Zn5, Al70Cu5Mg5Mn5Si10Zn5 and Al70Cu5Mg5Si10Zn5Zr5. Thus, all the studied alloys were classified as MEAs since their ΔSconf values are between 1R and 1.5 R.

In Fig. 1, the thermodynamic calculations of equilibrium phases as a function of temperature were calculated using Thermo-Calc software and TCAL5 database43. According to previous works44,45,46, the use of this database in Al-based HEAs and CCAs shows a good agreement with the experimental results. It should be noted that calculations were made for homogeneous alloys and not considering impurities, casting defects or oxides formed during the casting process. Moreover, it is well known that casting is not an equilibrium process. So, the studied alloys are not supposed to be in total thermodynamic equilibrium. The phase diagrams in Fig. 1 predicted at least the formation of major FCC (L12), Al2Cu (C16), Diamond (A4), Q-AlCuMgSi and V-phase (Mg2Zn11) in all the alloys at RT, except in Al70Cu5Mg5Si10Zn5Zr5 alloy. FCC (L12) refers to an ordered FCC phase closely related to the L12 structures (Strukturbericht notation). The disordered structure of FCC (A1) solution transformed into ordered FCC (L12), due to the complex composition of the alloys. The V-phase, which precipitated from the FCC solid solution, was the last precipitated phase in all the alloys, and the precipitation range was about 300 °C.

Figure 1(a) shows the equilibrium phase mole fraction of Al65Cu5Fe5Mg5Si15Zn5 alloy as a function of temperature. The phase diagram also predicted the formation of Al9Fe2Si2 (also known as β-Al4.5FeSi) at RT. The liquidus and solidus temperatures were 817 °C and 461 °C, respectively. Below solidus temperature, only V-phase was precipitated, at 329 °C. Thus, from CALPHAD calculations Al65Cu5Fe5Mg5Si15Zn5 alloy consisted of an ordered FCC solid-solution (30%) and five ICs (70%) at RT, with the main phase being Al9Fe2Si2 (33%). Figure 1(b) shows the phase diagram of Al65Cu5Mg5Ni5Si15Zn5 alloy as a function of temperature. The phase diagram predicted a similar phase equilibrium that is close to that obtained previously in Fig. 1(a) at RT. But with the difference of obtaining Al3Ni (D011) instead of Al9Fe2Si2 phase. The liquidus and solidus temperatures were 716 °C and 488 °C, respectively. Some qualitative and quantitative phase transformations were calculated below solidus temperature. The Al3Ni2 phase, which was the major IC near liquidus temperature disappeared at 362 °C. The Q-phase was expected to precipitate at 382 °C, indicating that the Cu absorption of this phase led to the transformation of Al3Ni2 into an Al3Ni. The phase constitution of Al3Ni phase was (Al,Ni)0.75Ni0.25 and did not admit Cu. Instead, Al3Ni2 was calculated with a phase constitution of (Al, Si)3(Ni,Cu)2(Ni)1. So, the alloy consisted of a major ordered FCC solid-solution (40%) and five ICs (60%) at RT, with the main IC being Al3Ni (20%). Figure 1(c) shows the equilibrium phase mole fraction of Al70Cr5Cu5Mg5Si10Zn5 alloy as a function of temperature. The phase diagram also predicted the formation Al13Cr4Si4 at RT. The liquidus and solidus temperatures were 997 °C and 450 °C, respectively. The V-phase was stable at temperatures below 300 °C. From thermodynamic calculations in Fig. 1(c), it can be predicted that Al70Cr5Cu5Mg5Si10Zn5 alloy consist of an ordered FCC solid-solution (43%) and five ICs (57%) at RT, with the main IC being Al13Cr4Si4 (26%). The amount of this compound was stable below 692 °C. Figure 1(d) shows the equilibrium phase mole fraction of Al70Cu5Mg5Mn5Si10Zn5 alloy as a function of temperature. The diagram was closely related to the phase diagram in Fig. 1(c). The diagram also predicted the above-mentioned phases and the Al15Si2Mn4 compound at RT. The liquidus and solidus temperatures were 817 °C and 447 °C, respectively. From thermodynamic calculations in Fig. 1(d), it can be predicted that Al70Cu5Mg5Mn5Si10Zn5 alloy consisted of an ordered FCC solid-solution (39%) and five ICs (61%) at RT, with the main IC being Al15Si2Mn4 (29%). The amount of this compound was stable bellow 681 °C. Figure 1(e) shows the equilibrium phase mole fraction of Al70Cu5Mg5Si10Zn5Zr5 alloy as a function of temperature. The phase diagram is significantly more complex compared with previously calculated diagrams in Fig. 1(a–d). The phase diagram predicted the formation of major FCC (L12), Al2Cu (C16), Q-AlCuMgSi, Si2Zr (C49), C14 Laves (Zn2Mg) phase and FeB (B27) at RT. The phase composition of FeB phase was (Zr)(Si, Zn). The liquidus temperature was over 1100 °C and solidus temperature was 454 °C. Many phase transformations were calculated below solidus temperature, resulting in a microstructure of an ordered FCC solid-solution (60%) and five ICs (40%) at RT, with the main IC being Al2Cu (13%).

Microstructure characterization

The overall bulk composition of the alloys was estimated using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) equipped with an energy dispersive X-ray spectrometry (EDS) on large areas. At least three random measurements were made, and the overall values are presented in Table 1. The obtained results showed good approximations to target compositions of the alloys, which demonstrated that the manufacturing process was successfully performed, although oxidation was detected by SEM-EDS.

The optical microscopy (OM) image of Al65Cu5Fe5Mg5Si15Zn5 alloy is shown in Fig. 2(a). The microstructure of the alloy revealed that shrinkage porosity was distributed near the plate-like phase. This defect was caused by metal reducing its volume during solidification, and its inability to feed shrinkage around complex morphology of the phase. A magnified OM image is shown in Fig. 2(b), where a mixture of different phases and brightest matrix phase were observed. At least five phases (A, B, C, D and E) with different contrasts were observed. In Fig. 2(c), dark irregular blocky-shape phase (A) were observed in the microstructure of Al65Cu5Mg5Ni5Si15Zn5 alloy. The magnified OM image of the alloy is shown in Fig. 2(d), a mixture of different phases (B, C, D and E) and a brightest matrix phase were observed. In Fig. 2(e), the complex dendritic structure of Al70Cr5Cu5Mg5Si10Zn5 alloy is shown, which was divided by net-like interdendritic structure and different phases. The magnified OM image is shown in Fig. 2(f), the microstructure also showed a mixture of different phases (A, B, C, D and E) and brightest matrix phase. In Fig. 2(g), shrinkage porosity was observed in the microstructure of Al70Cu5Mg5Mn5Si10Zn5 alloy. The magnified OM image of Al70Cu5Mg5Mn5Si10Zn5 is shown in Fig. 2(h), the image revealed that the microstructure was composed of at least five phases (A, B, C, D and E) and brightest matrix phase. In Fig. 2(i), shrinkage porosity was observed in the microstructure of Al70Cu5Mg5Si10Zn5Zr5 alloy. The OM image also showed the formation of dark irregular blocky-shape phase (A), but these were much smaller in size than previously observed phase in Fig. 2(c). The magnified OM image is shown in Fig. 2(j), a mixture of randomly distributed phases (B, C, D and E) were observed in the matrix.

According to OM images in Fig. 2, a multiphase character can be expected for the manufactured alloys. The different images confirmed a heterogeneous microstructure composed of at least five phases and major FCC matrix. So, CALPHAD thermodynamic modelling successfully predicted the number of constituent phases at RT.

The XRD patterns in Fig. 3 showed at least the formation of FCC solid solution (Space Group = 225), Si (S.G. = 227) and V-Mg2Zn11 (S.G. = 218) in all the alloys. The XRD pattern in Fig. 3(a) also showed the formation of Al2Cu (S.G. = 140), Al4Cu2Mg8Si7 (S.G. = 174) and Al9Fe2Si2 phase (S.G. = 14) in Al65Cu5Fe5Mg5Si15Zn5 alloy. The experimental results obtained by XRD technique and CALPHAD simulation in Fig. 2(a) showed a good agreement. Figure 3(b) detailed the XRD pattern of Al65Cu5Mg5Ni5Si15Zn5 alloy. The pattern also showed the formation of Al3Ni (S.G. = 62), Al3Ni2 (S.G. = 164) and Mg2Si (S.G. = 225). Thus, FCC, Si, V-Mg2Zn11 and Al3Ni predicted phases were observed, but Al2Cu and Al4Cu2Mg8Si7 phases were not indexed. The XRD pattern showed the formation of Al3Ni2 and Mg2Si compounds at RT, but these phases were predicted at temperatures above 358 °C and 382 °C, respectively. Figure 3(c) detailed the XRD pattern of Al65Cu5Mg5Ni5Si15Zn5 alloy. The XRD pattern also showed the formation of Mg2Si and Al13Cr4Si4 (S.G. = 216) phases. The other indexed phases showed good agreement with CALPHAD calculations in Fig. 2(c).

Figure 3(d) detailed the XRD pattern of Al70Cu5Mg5Mn5Si10Zn5 alloy. The diagram is very similar to the diagram represented in Fig. 3(c), but Al4MnSi (S.G. = 194) phase was observed instead of Al13Cr4Si4 indexed in Fig. 3(c). In this case, the formation of the Mg2Si phase mentioned above was also observed. Figure 3(e) detailed the XRD pattern of Al70Cu5Mg5Si10Zn5Zr5 alloy. The diagram showed similar diffraction peaks to those observed in Fig. 3(c,d). But, τ1-(Al,Zr,Si) (S.G. = 194) phase was indexed instead of Al13 Cr4 Si4 and Al4MnSi phases. The experimental result showed some discrepancies with thermodynamics results in Fig. 2(e). Phase diagram predicted the formation of FCC, Al2Cu, Q-AlCuMgSi, Si2Zr, C14 Laves (Zn2Mg) and FeB phases at RT. Thus, Si2Zr, C14 Laves (Zn2Mg) and FeB phases were not observed by XRD.

To reveal the qualitative chemical compositions of the regions, EDS mappings were obtained in Fig. 4. For a better understanding of the maps, oxygen was neglected due to the insignificant amount that it represented in the composition of the alloys. Figure 4(a) showed the complex microstructure of the Al65Cu5Fe5Mg5Si15Zn5 alloy. The matrix is rich in Al with a small amount of Zn. This region corresponds to FCC phase detected by XRD. In the remaining space, Al(Cu)-rich region was distinguished, which agrees well with Al2Cu compound obtained by XRD measurements and thermodynamic calculations. Si was segregated in two different regions. The first one, it was mainly composed of Si and it was surrounded by the matrix. The second region, although rich in Si, was also composed of Al and Fe. It presented a plate-like morphology and it was related to Al9Fe2Si phase, this phase was not distributed homogeneously in Fig. 4(a). The brightest region was mainly composed of Zn and a small amount of Mg. This region was related to V-Mg2Zn11 phase. Finally, Al-Mg-Si(Cu)-rich region was distinguished, and this region corresponded to the above defined Q-phase.

In Fig. 4(b), two types of needle-like regions and dark blocky-shape precipitates are distributed in the matrix of Al65Cu5Mg5Ni5Si15Zn5 as-cast alloy. The matrix was rich in Al and Zn, with a small amount of Cu and Si. From EDS mapping, the longest needle-like region was composed of Al and Ni. This was consistent with the phase composition of Al3Ni compound predicted by Thermo-Calc. The second needle-like region presented similar morphology, but it was found that quite a few concentrations of Cu were dissolved in the region. This Cu absorption leaded to the formation of Al3Ni2 phase, which was not supposed to be in thermodynamic equilibrium at RT. The phase diagram in Fig. 1(b) shifted the formation of Al3Ni phase at temperatures below 380 °C. At this temperature, Al3Ni and Q-AlCuMgSi phases precipitated from Al3Ni2. In the XRD pattern of Fig. 3(b), Al2Cu and Q-AlCuMgSi phases were not observed. Therefore, according to the observations, Cu got trapped in Al3Ni2 phase, avoiding the formation of Al2Cu and Q-AlCuMgSi phases. In Al65Cu5Mg5Ni5Si15Zn5 alloy, Si was also segregated in two different regions, forming Si-rich phase and Mg-Si-rich blocky-morphology region. This blocky region corresponded to previously defined Mg2Si phase. The brightest region was mainly composed of Zn and a small amount of Mg. This region was related to V-Mg2Zn11 phase defined by XRD.

Figure 4(c) shows Al-rich dendritic region that was enriched with Zn. The Fig. 4(c) also shows that Al2Cu compound was precipitated in the interdendritic space. There were many non-uniform particles dispersed in the microstructure. These particles presented irregular blocky-form and were composed of Al, Cr and Si. These particles were correlated to Al13Cr4Si4 phase. The brightest region in the interdendritic space, it was mainly composed of Zn and a small amount of Mg. This region was corresponded to Mg2Zn11 phase. Finally, the Chinese script region was composed of the matrix and Mg-Si-rich skeleton-like precipitates. This region presented different morphology than the one shown in Fig. 4(a), but quite similar qualitative elemental composition.

In Fig. 4(d), the as-cast microstructure consists of a dominant set of coarse Al(Zn) dendrites with a minor set of bright precipitates randomly distributed in the dark background. The dendritic structure was rich in Al and is also composed of small amounts of Cu and Zn. The interdendritic space was rich in Al and Cu, corresponding to Al2Cu phase. The eutectic region was composed of Si-rich particles precipitated in Al-rich dendrites. The Zn(Mg)-rich region was correlated to V-Mg2Zn11 phase. A region composed of Al, Mn and Si with blocky-morphology was distinguished, and this region was correlated to Al4MnSi phase defined by XRD in Fig. 3(d). Finally, an irregular dark blocky-shape Mg-Si-rich region was distinguished. This region corresponded to Mg2Si phase defined by XRD.

In Fig. 4(e) Al(Zn)-rich dendrites and Al-Cu-rich interdendritic regions are shown. These regions corresponded to FCC and Al2Cu phases respectively. The eutectic region was composed of Si-rich particles precipitated in Al(Zn) dendrites. This eutectic region was also observed in Al70Cu5Mg5Mn5Si10Zn5 alloy. The darkest region in SEM image corresponded to Mg-Si-rich region, correlated to Mg2Si phase. The brightest region was composed of Al, Si and Zr, and it presented blocky-morphology, and was not homogenously distributed in the microstructure of the alloy. So, the formation of τ1-(Al,Zr,Si) phase was confirmed in Fig. 4(a). The chemical composition of Al-Zr(Si)-rich phases obtained in the present study was far from the stoichiometric composition of the Si2Zr and FeB ((Zr)(Si,Zn)) phases predicted by Thermo-Calc. The reason for the discrepancies between CALPHAD and experimental results was that although TCAL5 database contains assessments of 87 ternaries43, the ternary Al-Si-Zr system is not assessed. Therefore, the predictions of binary compounds of Si-Zr in Fig. 1(d) may not have been entirely correct. Finally, the Zn(Mg)-rich region was correlated to V- Mg2Zn11 phase. The phase diagram in Fig. 2(e) shows that the formation sequence of the phases was FeB, Si2Zr, FCC, Mg2Si, Al2Cu, V-phase, Q-phase and finally, C14 Laves phase. Thus, the observation of Mg2Si phase in the diffraction diagram meant that Q-phase could not be formed from Mg2Si. Subsequently, C14 Laves phase was not precipitated from Q-phase. Thus, the experimental observations of the Al70Cu5Mg5Si10Zn5Zr5 as-cast alloy corresponded only partially to the predictions in Fig. 2(e).

The Mg2Si phase was not expected to be in thermodynamic equilibrium at RT. But XRD and SEM-EDS results clearly showed that Mg2Si phase was formed in Al65Cu5Mg5Ni5Si15Zn5, Al70Cr5Cu5Mg5Si10Zn5, Al70Cu5Mg5Mn5Si10Zn5 and Al70Cu5Mg5Si10Zn5Zr5 alloys. So, the quantitatively chemical compositions of Mg-Si-rich regions in Fig. 2(b–e) were analysed using SEM-EDS in Table 2.

The compositions in Table 2 revealed that Mg2Si phase was oxidized, due to the high reactivity of Mg at the temperatures reached up during the melting. The chemical composition of Mg-Si-rich regions in Al65Cu5Mg5Ni5Si15Zn5, Al70Cu5Mg5Mn5Si10Zn5 and Al70Cu5Mg5Si10Zn5Zr5 phases was very similar. The phases presented typical blocky morphology of Mg2Si compound, as can be observed in Fig. 4(b,d,e). On the other hand, in Al70Cr5Cu5Mg5Si10Zn5 alloy, the absorption of a small amount (12 at.%) of Al modified the blocky morphology into a Chinese script morphology. But this was only confirmed in Al70Cr5Cu5Mg5Si10Zn5 alloy, and the reasons for this have not been determined. The Chinese script phase is preferred because it is less detrimental to mechanical properties.

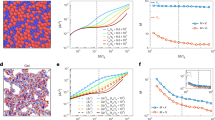

Mechanical properties

Up to the present, compressive properties and Vickers’s microhardness are the most reported properties studied for MEAs, HEAs and CCAs. In Table 3, the density and compressive mechanical properties with the standard deviations of the manufactured MEAs were summarized. Figure 5(a) shows the engineering compressive stress-strain curves of the manufactured MEAs. In this study, the fracture strength and the plastic strain were defined as the maximum stress and the maximum deformation in the stress-strain curve under each testing condition. The experimental scatter was 2–3% for the maximum compressive deformation. The Al65Cu5Fe5Mg5Si15Zn5 and Al65Cu5Mg5Ni5Si15Zn5 alloys had high RT strength (σmax = 482 MPa and σmax = 594 MPa) but showed a true compressive fracture strain of only 1%. In the case of Al65Cu5Fe5Mg5Si15Zn5, the brittle behaviour is due to Al9Fe2Si2 phase, which is a well-known phase that decreases the ductility of the Al alloys. The entropy of the system (1,2 R) was not enough to avoid the formation of this undesirable phase. In Al65Cu5Mg5Ni5Si15Zn5 the brittle behaviour was attributed to the large size of the observed oxides in Fig. 2(c). The Al70Cr5Cu5Mg5Si10Zn5 alloy combines the best results in terms of ductility-strength. It was reported a σy of 490 MPa with a maximum nominal plastic strain of 6%. The microstructure of Al70Cr5Cu5Mg5Si10Zn5 alloy in Fig. 2(f) showed the formation of beneficial Chinese script phase instead of the brittle blocky Mg2Si phase. Moreover, the size and distribution of the main IC (Al13Cr4Si4) was less detrimental to the ductility, and porosity was not detected in Fig. 2(e). The Al70Cu5Mg5Mn5Si10Zn5 alloy exhibited very high compressive strength, but the deformation values dropped below 2%. The Al70Cu5Mg5Si10Zn5Zr5 alloy, which was designed to have the largest volume of ductile α-Al matrix, also exhibited plastic deformability and a very high compressive σy of 565 MPa. The maximum deformation reached up to 4%. Both alloys presented some shrinkage porosity.

(a) Compressive engineering stress–strain curves of manufactured Al65Cu5Fe5Mg5Si15Zn5 (MEA-1), Al65Cu5Mg5Ni5Si15Zn5 (MEA-2), Al70Cr5Cu5Mg5Si10Zn5 (MEA-3), Al70Cu5Mg5Mn5Si10Zn5 (MEA-4) and Al70Cu5Mg5Si10Zn5Zr5 (MEA-5) MEAs at RT. (b) Materials property space for compressive yield strength vs density at RT of manufactured alloys, related works and conventional lightweight alloys.

In terms of microhardness testing, the manufactured alloys also showed good performance. The average Vickers microhardness values with standard deviations are 235 ± 85 HV0.1, 260 ± 32 HV0.1, 200 ± 18 HV0.1, 264 ± 57 HV0.1 and 220 ± 37 HV0.1, respectively. No cracks were observed during indentation test, which means that all the alloys still possess the potential plastic deformability. Although some alloys presented poor ductility. Microstructure of Al70Cu5Mg5Mn5Si10Zn5 alloy, which showed the highest hardness value, exhibited the same influence on hardness as for strength. The second-phase strengthening mechanism of this alloy caused by the Al4MnSi phase was more pronounced, decreasing the ductility, but increasing the hardness and strength. The standard deviation of Al65Cu5Fe5Mg5Si15Zn5 and Al70Cu5Mg5Si10Zn5Zr5 alloys was significantly higher in terms of strength (Table 3) and hardness values. This is due to the large size and the not uniformly distributed regions in Fig. 4(a,e), Al-Fe(Si) and Al-Zr(Si), respectively.

A comparison of the strength and density of these MEAs with related works in the field of LWMEAs and commercial lightweight materials are given in Fig. 5(b). The materials in the present work are very well situated in the strength/density diagrams. The manufactured MEAs are superior in terms of strength/density to previously studied MEAs and most of conventional alloys. Furthermore, MEAs fill the gap between Al alloys, Mg alloys and Ti alloys.

Discussion

In this work, five new lightweight non-equiatomic MEAs were studied, namely Al65Cu5Fe5Mg5Si15Zn5, Al65Cu5Mg5Ni5Si15Zn5, Al70Cr5Cu5Mg5Si10Zn5, Al70Cu5Mg5Mn5Si10Zn5 and Al70Cu5Mg5Si10Zn5Zr5. The experimental techniques revealed that all studied MEAs were a mixture of α-Al matrix and five intermetallic phases. The major intermetallic phase in all the alloys was mainly composed of Al-Fe, Al-Ni, Al-Cr, Al-Mn or Al-Zr. The present results show that it was difficult to form solid solutions phases in Al based Medium Entropy Alloys. The competition between enthalpy and entropy promoted the formation of ICs, due to the high negative mixing enthalpy of Al with transition metals. The role of each transition metal added to both systems was to promote the formation of the main IC, without affecting the formation of the remaining phases.

Some discrepancies between CALPHAD methodology and experimental values are clearly visible. The Q-AlCuMgSi phase only was experimentally observed in Al65Cu5Fe5Mg5Si15Zn5 alloy. The Mg2Si phase was not supposed to be in thermodynamic equilibrium at RT, but the peaks at 24°, 41° and 73° in the XRD patterns indicated the formation of this phase, instead of the predicted Q-AlCuMgSi. The phase diagrams in Fig. 2 showed that Q-AlCuMgSi precipitated from Mg2Si at 382 °C. Therefore, the experimental observation of Mg2Si instead of Q-AlCuMgSi phase at RT, suggested that Mg and Si were trapped in Mg2Si phase due to the oxidation of Mg, avoiding the precipitation of Q-AlCuMgSi. This observation did not contribute to the formation of V-Mg2Zn11 phase (which is composed of a small amount of Mg) since Mg precipitated from the FCC solid solution phase at temperatures below 300 °C. The oxidation of Mg was due the long-time of exposure of the molten alloy to high temperatures and the impurities in the alloying tablets. All the alloys reached to similar maximum temperatures during melting and were poured in the die in the same temperature range. But all the alloys exhibited oxidized Mg2Si phase, except Al65Cu5Fe5Mg5Si15Zn5 alloy, that was the only alloy in which only pure elements were used.

The Al70Cu5Mg5Si10Zn5X5 system exhibited the best mechanical properties. Specifically, Al70Cr5Cu5Mg5Si10Zn5 alloy showed the best mechanical properties in terms of strength-ductility. The main reason for that, was the transformation of the blocky morphology into a more desirable Chinese script morphology of Mg2Si phase, and the size and distribution of the Al13Cr4Si4 compound. In contrast to the rest of the alloys, with large ICs not uniformly distributed in their microstructure.

The casting process has shown that lightweight MEAs with high strength and high hardness can be adapted to large-scale industrial production. However, the melting process should be slightly adjusted to avoid shrinkage porosity and oxidization of Mg2Si phase. Oxidation of the Mg2Si phase can be avoided by using pure elements or mother alloys, but the use of briquettes should be avoided. Although the microstructure of the alloys presents some defects such as shrinkage porosity and oxides formation, these alloys have proven to have numerous possible applications, due to the viability of the industrial scale manufacturing and the obtained results in terms of mechanical properties. But the manufacturing method should be optimized to improve the ductility. Furthermore, the alloys were studied in the as-cast state, so the standard heat treatment for Al alloys could improve the moderate ductility of the alloys. As a further work, an exhaustive study of the mechanical properties, and especially the tribological properties of the as-cast and heat-treated alloys should be studied.

Methods

Design of the alloys

The software Thermo-Calc (v. 2017b, Thermo-Calc Software AB, Stockholm, Sweden)47 in conjunction with the TCAL5 thermodynamic database was used for calculations of the equilibrium phases as a function of temperature.

Materials preparation

Experimental alloys were prepared in an induction furnace VIP-I (Inductotherm Corp., Rancocas, USA) in an alumina crucible using 99.95% pure Al, Cu, Fe, Mg, Si and Zn. Tablets of Al-Cr, Al-Mn, Al-Ni and Al-Zr containing 75 wt.% of Cr, 80 wt., 80 wt.% of Mn, 80 wt.% of Ni and 75 wt.% of Zr respectively were used. Approximately 4.5 kg were obtained for each alloy. The melting process can be divided into three stages. Firstly, Al and Si were placed at the bottom of the crucible to guarantee a bath base where the other elements were dissolved from highest to lowest melting point. In the second stage, the variable element of each alloy (Fe, Ni, Cr, Mn or Zr) was added to the molten alloy. The maximum temperature was reached at this stage. Finally, Cu, Zn and Mg were added respectively and held around 750 °C, at least 10 minutes to reach complete dissolution. Then, the melt was poured manually into a steel mould. The nominal liquidus temperatures obtained by Thermo-Calc, maximum temperatures reached up during the melting and casting temperatures are represented in Table 4.

Microstructural and elemental characterization

Several ingots of approximately 200 mm (length) × 80 mm (width) × 40 mm (thickness) were obtained for each alloy. The samples for optical microscopy (OM) and microhardness test were cut from the ingots and prepared according to standard metallographic procedures, by hot mounting in conductive resin, grinding, and polishing. The X-ray diffraction (XRD) equipment used to characterize the crystal structures of the alloys was a model D8 ADVANCE (BRUKER, Karlsruhe, Germany), with Cu Kα radiation, operated at 40 kV and 30 mA. The diffraction diagrams were measured at the diffraction angle 2θ, range from 10° to 90° with a step size of 0.01°, and 1.8 s/step. The powder diffraction file (PDF) database 2008 was applied for phase identification. The microstructure, the different regions and the averaged overall chemical composition of each sample were investigated by an optic microscope model DMI5000 M (LEICA Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany) and a scanning electron microscope (SEM), equipped with an energy dispersive X-ray spectrometry (EDS) model JSM-5910LV (JEOL, Croissy-sur-Seine, France).

Mechanical characterization

Cylindrical specimens for compression testing were machined from the ingots, with a diameter of 13 mm and a height of 26 mm, giving an aspect ratio of 1:2. Compression testing was performed using an MTS Insight 100 kN Extended Length (MTS Systems Corporation, Eden Prairie, USA) at RT with a strain rate of 0.001 s−1. For the accurate measurement of Young’s modulus, clip-on extensometer mounted on the specimens were used. At least five specimens were performed to ensure the repeatability. Vickers microhardness FM-700 model (FUTURE-TECH, Kawasaki, Japan) was employed on the polished sample surface using a 0.1 kg load, applied for 10 s. At least 10 random individual measurements were made. Finally, density measurement was conducted using the Archimedes method.

References

Cantor, B. Multicomponent and high entropy alloys. Entropy 16, 4749–4768 (2014).

Yeh, J. W. et al. Nanostructured high-entropy alloys with multiple principal elements: Novel alloy design concepts and outcomes. Adv. Eng. Mater. 6, 299–303+274 (2004).

Cantor, B., Chang, I. T. H., Knight, P. & Vincent, A. J. B. Microstructural development in equiatomic multicomponent alloys. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 375–377, 213–218 (2004).

Yeh, J. W. Alloy design strategies and future trends in high-entropy alloys. JOM, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11837-013-0761-6 (2013).

Zhang, Y. et al. Microstructures and properties of high-entropy alloys. Prog. Mater. Sci, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmatsci.2013.10.001 (2014).

Zhang, W., Liaw, P. K. & Zhang, Y. Science and technology in high-entropy alloys. Sci. China Mater. 61, 2–22 (2018).

Miracle, D. B. & Senkov, O. N. A critical review of high entropy alloys and related concepts. Acta Materialia, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actamat.2016.08.081 (2017).

Gorsse, S., Miracle, D. B. & Senkov, O. N. Mapping the world of complex concentrated alloys. Acta Mater. 135, 177–187 (2017).

Gao, M. C., Liaw, P. K., Yeh, J.-W. & Zhang, Y. High-entropy alloys: Fundamentals and applications. High-Entropy Alloys: Fundamentals and Applications, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-27013-5 (2016).

Kumar, A. & Gupta, M. An Insight into Evolution of Light Weight High Entropy Alloys: A Review. Metals (Basel). 6, 199 (2016).

Jablonski, P. D., Licavoli, J. J., Gao, M. C. & Hawk, J. A. Manufacturing of High Entropy Alloys. Jom 67, 2278–2287 (2015).

Raabe, D., Tasan, C. C., Springer, H. & Bausch, M. From high-entropy alloys to high-entropy steels. Steel Res. Int. 86, 1127–1138 (2015).

Li, Z., Pradeep, K. G., Deng, Y., Raabe, D. & Tasan, C. C. Metastable high-entropy dual-phase alloys overcome the strength–ductility trade-off. Nature, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature17981 (2016).

Li, Z., Tasan, C. C., Springer, H., Gault, B. & Raabe, D. Interstitial atoms enable joint twinning and transformation induced plasticity in strong and ductile high-entropy alloys. Sci. Rep. 7, 40704 (2017).

Li, Z. & Raabe, D. Strong and Ductile Non-equiatomic High-Entropy Alloys: Design, Processing, Microstructure, and Mechanical Properties. Jom, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11837-017-2540-2 (2017).

Li, Z. & Raabe, D. Influence of compositional inhomogeneity on mechanical behavior of an interstitial dual-phase high-entropy alloy. Mater. Chem. Phys, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matchemphys.2017.04.050 (2017).

Nene, S. S. et al. Enhanced strength and ductility in a friction stir processing engineered dual phase high entropy alloy. Sci. Rep. 7 (2017).

Zhang, H. et al. Novel high-entropy and medium-entropy stainless steels with enhanced mechanical and anti-corrosion properties. Mater. Sci. Technol. (United Kingdom) 1–8, https://doi.org/10.1080/02670836.2017.1416907 (2017).

Laws, K. J. et al. High entropy brasses and bronzes - Microstructure, phase evolution and properties. J. Alloys Compd. 650, 949–961 (2015).

Ma, Y. et al. Dynamic shear deformation of a CrCoNi medium-entropy alloy with heterogeneous grain structures. Acta Mater. 148, 407–418 (2018).

Laplanche, G. et al. Reasons for the superior mechanical properties of medium-entropy CrCoNi compared to high-entropy CrMnFeCoNi. Acta Mater. 128, 292–303 (2017).

Ding, Z. Y., He, Q. F., Wang, Q. & Yang, Y. Superb strength and high plasticity in laves phase rich eutectic medium-entropy-alloy nanocomposites. Int. J. Plast. 106, 57–72 (2018).

Pešička, J. et al. Structure and mechanical properties of FeAlCrV and FeAlCrMo medium-entropy alloys. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 727, 184–191 (2018).

Gali, A. & George, E. P. Tensile properties of high- and medium-entropy alloys. Intermetallics 39, 74–78 (2013).

Zhang, M., Zhou, X., Zhu, W. & Li, J. Influence of Annealing on Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of Refractory CoCrMoNbTi0.4 High-Entropy Alloy. Metall. Mater. Trans. A, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11661-018-4472-z (2018).

Gludovatz, B. et al. Exceptional damage-tolerance of a medium-entropy alloy CrCoNi at cryogenic temperatures. Nat. Commun. 7, 1–8 (2016).

Li, W., Liaw, P. K. & Gao, Y. Fracture resistance of high entropy alloys: A review. Intermetallics 99, 69–83 (2018).

Carroll, R. et al. Experiments and Model for Serration Statistics in Low-Entropy, Medium-Entropy, and High-Entropy Alloys. Sci. Rep. 5 (2015).

Li, R., Gao, J. C. & Fan, K. Study to Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of Mg Containing High Entropy Alloys. Mater. Sci. Forum 650, 265–271 (2010).

Li, R., Gao, J.-C. & Fan, K. Microstructure and mechanical properties of MgMnAlZnCu high entropy alloy cooling in three conditions. Mater. Sci. Forum 686, 235–241 (2011).

Yang, X., Chen, S. Y., Cotton, J. D. & Zhang, Y. Phase Stability of Low-Density, Multiprincipal Component Alloys Containing Aluminum, Magnesium, and Lithium. Jom 66, 2009–2020 (2014).

Baek, E. J. et al. Effects of ultrasonic melt treatment and solution treatment on the microstructure and mechanical properties of low-density multicomponent Al70Mg10Si10Cu5Zn5alloy. J. Alloys Compd. 696, 450–459 (2017).

Ahn, T. Y., Jung, J. G., Baek, E. J., Hwang, S. S. & Euh, K. Temperature dependence of precipitation behavior of Al–6Mg–9Si–10Cu–10Zn–3Ni natural composite and its impact on mechanical properties. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 695, 45–54 (2017).

Ahn, T. Y., Jung, J. G., Baek, E. J., Hwang, S. S. & Euh, K. Temporal evolution of precipitates in multicomponent Al–6Mg–9Si–10Cu–10Zn–3Ni alloy studied by complementary experimental methods. J. Alloys Compd. 701, 660–668 (2017).

Shao, L. et al. A Low-Cost Lightweight Entropic Alloy with High Strength. J. Mater. Eng. Perform, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11665-018-3720-0 (2018).

Zhou, Y. et al. Design of non-equiatomic medium-entropy alloys. Sci. Rep. 8, 1DUMMY (2018).

Yeh, J. W. Physical Metallurgy of High-Entropy Alloys. JOM 67, 2254–2261 (2015).

Gorsse, S. & Tancret, F. Current and emerging practices of CALPHAD toward the development of high entropy alloys and complex concentrated alloys. J. Mater. Res. 1–25, https://doi.org/10.1557/jmr.2018.152 (2018).

Gao, M. C. et al. Thermodynamics of concentrated solid solution alloys. Curr. Opin. Solid State Mater. Sci. 21, 238–251 (2017).

Zhang, C. & Gao, M. C. CALPHAD modeling of high-entropy alloys. In High-Entropy Alloys: Fundamentals and Applications 399–444, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-27013-5_12 (2016).

Tsai, M. H. Three strategies for the design of advanced high-entropy alloys. Entropy 18 (2016).

Robles-Hernandez, F. C., Herrera Ramírez, J. M. & Mackay, R. Al-Si Alloys. Automotive, Aeronautical, and Aerospace Applications., https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-58380-8 (Springer International Publishing, 2017).

Chen, H. L., Chen, Q. & Engström, A. Development and applications of the TCAL aluminum alloy database. Calphad Comput. Coupling Phase Diagrams Thermochem. 62, 154–171 (2018).

Sanchez, J. M. et al. Compound Formation and Microstructure of As-Cast High Entropy Aluminums. Metals (Basel). 8, 167 (2018).

Sanchez, J. M., Vicario, I., Albizuri, J., Guraya, T. & Garcia, J. C. Phase prediction, microstructure and high hardness of novel light-weight high entropy alloys. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 1–9, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmrt.2018.06.010 (2018).

Sun, W., Huang, X. & Luo, A. A. Phase formations in low density high entropy alloys. Calphad Comput. Coupling Phase Diagrams Thermochem. 56, 19–28 (2017).

Andersson, J. O., Helander, T., Höglund, L., Shi, P. & Sundman, B. Thermo-Calc & DICTRA, computational tools for materials science. Calphad Comput. Coupling Phase Diagrams Thermochem. 26, 273–312 (2002).

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support of the Basque Government through the project Elkartek: KK-2017/00007 and KK-2018/00015.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors have made contributions to this paper. J.M. Sanchez wrote this paper. J.M. Sanchez, I. Vicario and E.M. Acuña conducted the experiments. I. Vicario, J. Albizuri and T. Guraya revised the paper. All authors discussed the results.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sanchez, J.M., Vicario, I., Albizuri, J. et al. Design, Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of Cast Medium Entropy Aluminium Alloys. Sci Rep 9, 6792 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-43329-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-43329-w

This article is cited by

-

Macrostructure, Microstructure, and Mechanical Properties of Al0.2CoCrFeNi High-Entropy Alloy Produced by Vacuum Induction Melting

Transactions of the Indian Institute of Metals (2024)

-

Lightweight Al-based entropy alloys: Overview and future trend

Science China Materials (2024)

-

Development of a Low Entropy, Lightweight, Multicomponent, High Performance (Hardness + Strength + Ductility) Magnesium-Based Alloy

JOM (2023)

-

Lightweight Medium Entropy Magnesium Alloy with Exceptional Compressive Strength and Ductility Combination

Journal of Materials Engineering and Performance (2021)

-

Lightweight AlCuFeMnMgTi High Entropy Alloy with High Strength-to-Density Ratio Processed by Powder Metallurgy

Metals and Materials International (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.