Abstract

The effects of the spin transition on the electronic structure, thermal expansivity and lattice thermal conductivity of ferropericlase are studied by first principles calculations at high pressures. The electronic structures indicate that ferropericlase is an insulator for high-spin and low-spin states. Combined with the quasiharmonic approximation, our calculations show that the thermal expansivity is larger in the high-spin state than in the low-spin state at ambient pressure, while the magnitude exhibits a crossover between high-spin and low-spin with increasing pressure. The calculated lattice thermal conductivity exhibits a drastic reduction upon the inclusion of ferrous iron, which is consistent with previous experimental studies. However, a subsequent enhancement in the thermal conductivity is obtained, which is associated with the spin transition. Mechanisms are discussed for the variation in thermal conductivity by the inclusion of ferrous iron and the spin transition.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

A spin transition can occur in some metal complexes due to various external factors, such as temperature, pressure, light irradiation and magnetic field. In the past two decades, the verification of the spin transition in Mg1-xFexO ferropericlase (Fp) and iron-bearing MgSiO3 perovskite (Pv) has become a research hotspot in geophysics1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25. Fp is the second most abundant mineral in the lower mantle and has attracted much attention due to its crucial role in the lower mantle. The conclusions of high-pressure studies indicated that ferrous iron undergoes a spin transition from a high-spin (HS, five d electrons up and one down, S = 2) state to a low-spin (LS, three d electrons up and three down, S = 0) state3,5,7,8,9,10,16,17,21. Previous works focused on the condition of the spin transition and the associated effects on the equation of state, elastic property and velocity and then described special features of the seismic velocity in the core-mantle boundary (CMB)2,10,11,14,15,18,19,20. At present, the effects of a spin transition on thermal expansivity (α) and lattice thermal conductivity (klatt) are still unclear and are useful for constraining the thermal structure of the Earth’s interior.

It is important for the parameter α to capture both the thermodynamic and the thermoelastic behaviors of a solid at high temperature. Various earlier studies focused on iron-free MgO by first principles, semiempirical and semiphenomenological calculations26,27,28,29,30. To our knowledge, the experimental value of α in (Mg,Fe)O Fp has only been reported at ambient pressure11,31. Theoretically, Wu et al.32 and Fukui et al.33 reported that the spin transition caused anomalies in the thermodynamic properties of Fp (Mg0.8125Fe0.1875O and Mg0.875Fe0.125O). Scanavino’s works showed that the inclusion of iron in the LS state results in a value of α that is smaller than that of MgO. However, the effect of ferrous iron in the HS state on α has not yet been investigated34,35. Mao et al.11 reported that α in HS Fp is slightly smaller than that in LS Fp at low pressure, while the corresponding data at high pressure is still absent.

As for klatt, many efforts have been dedicated to iron-free MgO, in both experimental and theoretical studies36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47. Manthilake et al.48 reported ferrous iron effects on klatt at relatively low pressures (8 and 14 GPa). Their results indicated that the incorporation of iron could result in a drastic decrease (~50%) in klatt. Goncharov et al.49 also demonstrated a large decrease at ambient condition (the measured klatt of Mg0.9Fe0.1O was 5.7 Wm−1K−1, ~10 times smaller than that of ferrous-free MgO). The above works verified a reduction by the inclusion of ferrous iron, but their measurements were at ambient condition or low pressures, which ignored the effect of the spin transition and may have caused a larger uncertainty. Recently, Ohta et al.50 measured klatt up to 111 GPa and indicated via a damped harmonic oscillator-phonon gas model that the spin transition from HS to LS reduced klatt. However, Stackhouse et al.51 presented a contrary conclusion based on a scaling relation. Therefore, more studies are obviously needed to obtain a consensus regarding klatt. In this work, we use first principles calculations to investigate the effects of the spin transition on the electronic structure, α and klatt.

Results and Discussions

Electronic structure

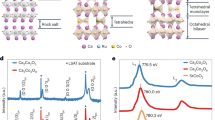

The standard local density approximation (LDA) calculation presents a stable structure with the shortest iron-iron distance, while the calculation using the LDA + U approach displays a stable configuration with a large iron-iron distance. In this work, the electronic structure calculations are performed using the configuration obtained by the LDA + U. The spin-polarized density of states (DOS) of Fp in the HS and LS states are shown in Fig. 1. For HS and LS Fp at ambient pressure, an energy gap is observed around the Fermi level, which is similar to that found in Tsuchiya et al.52. Meanwhile, the band gap increases with increasing pressure due to the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) shifting in the higher energy direction. The partial DOS of HS Fp (Fig. 1(b)) shows that the spin down channel determines the magnitude of the band gap. One t2g state (dyz) forms the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO), and the other two states of t2g constitute the LUMO. The two states of eg are split and empty at the higher energy level with respect to the t2g states. The spin transition from HS to LS modifies the electron configuration. The unsplit t2g and eg states comprise the HOMO and LUMO of LS Fp, respectively (Fig. 1(d)). In conclusion, the insulativity is retained after the spin transition, in which case heat is dominantly transported by conduction.

Thermal expansivity

We compare our results for MgO with those of previous experimental and theoretical studies at various pressures (0, 60 and 120 GPa), as shown in Fig. 2(a). Our results are in good accordance with previous studies. For example, at 0 GPa and 300 K, the calculated α in this work is 3.18 × 10−5 K−1, which is very close to the previous measurements and calculations (3.11 × 10−5~3.19 × 10−5 K−1)53,54,55,56,57. At higher pressures, the temperature dependence of α is small, and our calculations are similar to the theoretical results in Sushil et al.29. The measurements at 2000 K indicate that the values at 60 GPa and 120 GPa are 1.82 × 10−5 K−1 and 1.28 × 10−5 K−1, respectively. Taking into account the weak temperature dependence, our results are also in agreement with the measurements.

Figure 2(b) shows the temperature dependence of α in Mg0.75Fe0.25O Fp in the HS and LS states, and the results in previous works are also included33. At ambient condition, the calculated results of α are 3.18 × 10−5 K−1 and 3.38 × 10−5 K−1 for MgO and Mg0.75Fe0.25O in the HS state, respectively. The inclusion of ferrous iron results in a slight variation in α, which is consistent with the experimental observations32,58. Our calculated results are also in accordance with the theoretical calculations of Mg0.875Fe0.125O, which verify that the concentration of ferrous iron is low33,58. Now, we discuss the effect of the spin transition on α. In this work, the calculated α for LS Fp is 2.94 × 10−5 K−1 and smaller than that of HS Fp at ambient condition. The experimental study presented an α of 3.76 × 10−5 K−1 for HS Fp, which is slightly larger than 3.37 × 10−5 K−1 for LS Fp (circles in Fig. 2(b)). Thus, our calculations verify the measurement at ambient condition11. However, it can be found that the value of α in LS Fp is larger than that in HS Fp at higher pressures in our calculations. For example, at 120 GPa and 1500 K, the values are 1.24 × 10−5 K−1 and 1.15 × 10−5 K−1 for LS Fp and HS Fp, respectively, which means the magnitude of α exhibits a crossover between HS and LS Fp with increasing pressure, in accordance with a previous study for Mg0.875Fe0.125O33. Following Grüneisen’s law \(\alpha =\frac{\gamma }{{K}_{0}}\frac{{C}_{V}}{V}\), α is proportional to the Grüneisen parameter (γ) and heat capacity (CV) and inversely proportional to the bulk modulus (K0) and volume (V). Figure 3 presents these parameters for Mg0.75Fe0.25O Fp in the HS and LS states at 0, 60 and 120 GPa. Clearly, γ is the only parameter that show a transition with increasing pressure, and it mainly determines the variation in α due to the spin transition.

Thermal conductivity

Figure 4 shows klatt for MgO, and previous results based on experiments and simulations are also included. Our calculated klatt is in good agreement with previous theoretical studies within the numerical accuracy. For example, at ambient condition, our calculated value is 64.7 Wm−1K−1, which is comparable to the values of 53.7~66 Wm−1K−1 obtained by simulations36,43,44. Haigis et al.40 adopted classic molecular dynamics combined with the Green-Kubo method and obtained a value of ~110 Wm−1K−1, which is larger than other simulation and measurement values. This disagreement may derive from the use of empirical potentials that may not easily describe anharmonic interactions, which sensitively affect the calculation of klatt. The range of the experimental values is 40~60 Wm−1K−1, and our work is close to this range39,41,48. Generally, it can be found that the values obtained by simulations are higher than those obtained by experiments. The difference is largely attributed to two factors: (1) the calculations are based on an ideal crystal and do not account for the presence of defects in the experimental samples, which affects the scattering rate40,41; (2) the experimental measurements of klatt are based on a polycrystalline sample, which will result in an underestimation of the single-crystal klatt50.

Figure 5 shows klatt for Mg0.75Fe0.25O Fp at 300 K. The inclusion of ferrous iron reduces klatt both for HS Fp and LS Fp. Meanwhile, it is evident that klatt increases with the spin transition. At ambient condition, the calculated klatt of Mg0.75Fe0.25O Fp in the HS state is 5.19 Wm−1K−1. This is a significant reduction of ~92% compared to the value for MgO (64.7 Wm−1K−1) at the same condition (Fig. 4). Manthilake et al.48 indicated that the inclusion of ferrous iron (5% and 20%) leads to an ~50% decrease in klatt. Recent experimental measurements at ambient condition also reported klatt values of 4.2 ± 0.5 and 5.7 Wm−1K−1 for Mg0.81Fe0.19O Fp and Mg0.9Fe0.1O Fp, respectively, representing an ~90% reduction from that of MgO49,50. As such, our calculations are in line with the experimental measurements, substantiating the fact that the incorporation of ferrous iron into MgO leads to a drastic reduction in klatt.

In the following paragraphs, the mechanisms for the reduction in klatt by the inclusion of ferrous iron and the increase in klatt by the spin transition are discussed in detail. As seen from Eq. (1), the factors influencing klatt are the volume V, mode-contributed heat capacity CV, group velocity vg and phonon lifetime τ. At higher temperatures, CV approaches the classical value kB, Boltzmann’s constant. Therefore, CV does not influence klatt under mantle conditions. The volume of HS Fp increases slightly compared to that of MgO, and the volume of LS Fp decreases by ~0.18%. Surely, a weak variation in volume is not sufficient to explain the significant reduction in klatt (~92%). The phonon dispersions of MgO and Mg0.75Fe0.25O HS Fp are shown in Fig. 6(a). It is observed that the phonon frequencies and group velocities decrease by approximately 25% for both transversal and longitudinal acoustic modes due to the inclusion of ferrous iron, which then contribute to the reduction in klatt. The LO-TO splitting effect on the phonon spectrum and klatt are also discussed (Fig. 6(b)). The Γ-point of the optical phonon at higher frequencies (>150 rad/ps) is nondegenerate. Figure 7 shows the cumulative klatt with respect to frequency. Phonons with frequencies higher than 140 rad/ps almost do not contribute to klatt. Thus, the LO-TO splitting has a limited impact on klatt. The last term of the anharmonic scattering rates (reciprocal of the lifetime, τ−1) is plotted in Fig. 8. Stronger scattering rates are obtained for both HS Fp and LS Fp with respect to that of MgO, which also leads to a reduction in klatt.

The anharmonic scattering matrix elements depend on several factors: the third-order interatomic force constants (IFCs), weighted phase space and atomic mass. We identify an increase in the magnitude of a number of third-order IFCs for Mg0.75Fe0.25O Fp and MgO with the inclusion of ferrous iron. For example, at 135 GPa and 4000 K, the largest third-order IFC element of MgO is 74.7 eV/Å3, while that of Mg0.75Fe0.25O HS (LS) Fp increases to 109.7 (89) eV/Å3. The anharmonic scattering rates are closely related to third-order IFCs; therefore, the larger IFCs of Mg0.75Fe0.25O Fp give rise to an increase in the anharmonic scattering rates. A weighted phase space (W+, W−) for three-phonon scattering processes (P3) was explained by Li et al.59,60. The total phase space of a P3 process consists of two independent scattering channels, i.e., the adsorption process \(({P}_{3}^{+})\) and emission process \(({P}_{3}^{-})\). The scattering phase space is representative of all available three-phonon interacting channels in heat transfer, and an increase in W agrees with an increase in the scattering rates. Clearly, as shown in Fig. 9, \({W}^{\pm }\) of Mg0.75Fe0.25O HS Fp are generally larger than those of MgO, which suggests that Mg0.75Fe0.25O HS (LS) Fp displays larger scattering rates and shorter lifetimes and consequently a lower klatt. A larger mass leads to a smaller atomic displacement of a phonon excitation and therefore reduced anharmonic scattering rates. For Mg0.75Fe0.25O Fp, the mass of Fe is larger than that of Mg; thus, the difference in mass should play a role in the reduction in the scattering rates, leading to an increase in klatt. Overall, the reduction in klatt for Mg0.75Fe0.25O Fp is clarified from its relationship with the phonon group velocities, third-order anharmonic IFCs, weighted phase space, and atomic masses. The concurrent decrease in the group velocities and increase in the anharmonic scattering rates give rise to a reduction in klatt when ferrous iron is incorporated into MgO.

From Fig. 5, it can be found that the spin transition can give rise to an enhancement in klatt. At 90 GPa and 2500 K, klatt for HS Fp and LS Fp are 5.03 and 8.8 Wm−1K−1, respectively, with an approximate enhancement of 42.8%. Stackhouse et al.51 evaluated klatt for LS Fp based on the scaling relation and volume in Tsuchiya et al.8, and an enhancement in klatt was also obtained. Recently, an experimental work presented a contrary conclusion to our calculations. In their work, klatt was predicted with the damped harmonic oscillator-phonon gas model

where KT and γ are the isothermal bulk modulus and the Grüneisen parameter. Their work confirmed a substantial reduction in klatt for HS Fp with respect to the value for MgO and a further decrease was obtained with the spin transition50. Using the thermodynamic parameters in our calculations (kT increases and γ decreases with the spin transition), the value of \(\frac{\partial ln{k}_{{\rm{latt}}}}{\partial P}\) for LS Fp is indeed smaller than that for HS Fp, which amounts to a weak pressure dependence for LS Fp. In our calculations, the reference value of klatt at ambient temperature is 14.57 Wm−1K−1 for LS Mg0.75Fe0.25O Fp, which is much larger than the value for HS Fp (8.9 Wm−1K−1) and represents an enhancement caused by the spin transition. Here, we address the mechanism of the enhancement in klatt by the spin transition. As discussed above, CV and V have little influence on klatt; thus, the scattering rates and group velocities need further investigation. Figure 7 reveals that the scattering rates (τ−1) of Fp in the LS state are slightly smaller than those in the HS state, which supports the increase in klatt. The phonon dispersion (see Fig. 6(a)) indicates that the velocities in the longitudinal acoustic modes increase modestly with the spin transition, and those in the transverse acoustic modes are unaffected. Thus, the abovementioned characteristics contribute to the enhancement in klatt by the spin transition.

Conclusions

Using first principles calculations with the quasiharmonic approximation (QHA) and lattice dynamics, the effects of the spin transition in ferrous iron on the electronic structure, α and klatt of Fp, are investigated. The electronic structures calculated by the LDA + U indicate that the insulativity is retained after a spin transition from HS to LS and determines that the major mechanism of heat transfer is heat conduction for Fp at high pressure. Our calculations show that the magnitude of α in the HS state is larger than that in the LS state at ambient pressure, while the amplitude exhibits a crossover at higher pressure. The calculations of klatt for Fp confirm a drastic reduction in klatt due to the inclusion of ferrous iron. However, a subsequent increase associated with the spin transition is obtained. The concurrent decrease in the group velocities and increase in the anharmonic scattering rates give rise to a reduction in klatt when ferrous iron is incorporated into MgO.

Computational details

As far as (Mg,Fe)O Fp is concerned, the concentration of ferrous iron reached a maximum of ~46% in previous studies, and in this work, a concentration of 25% was selected. (Mg0.75Fe0.25)O was structured and obtained by the substitution of one Mg atom with one Fe atom in a MgO crystal cell (8 atoms in total). All cell parameters were fully relaxed.

In this work, first principles calculations based on density functional theory (DFT) were performed using the Vienna ab initio simulation package (VASP)61. The previous studies presented relations for describing the volume and spin state dependences of the strong correlative interaction (U) of Fp8,52, and the LDA + U was adopted for structure optimizations and calculations of free energies in this work62,63. For the U value, we first optimized the structure with the standard LDA and obtained the volume and then selected the U value from the relation between U and the volume presented in Tsuchiya et al.8,52. Lastly, the atomic positions were fully relaxed using the LDA + U approach. At different pressures, the U values are listed in Table 1. A plane wave basis set with a maximum kinetic energy of 600 eV was adopted. For the electronic structure calculations, an 8 × 8 × 8 k-point mesh generated by the Monkhorst-Pack scheme was used64. The convergence threshold for the total energy was set to 0.1 × 10−6 eV/cell, and the threshold for the atomic force was 10−4 eV/Å.

The second-order harmonic interatomic force constants (IFCs), phonon spectrum and thermal properties were calculated by VASP combined with a QHA implemented in PHONOPY software65. The dynamical matrix was constructed to solve the eigenvalue problem for the phonon frequencies at high-symmetry k-points. The phonon modes and frequencies at other general k-points were then computed by a Fourier transformation of the dynamical matrix in reciprocal space. All these calculations were based on 3 × 3 × 3 supercells of Mg4O4 and Mg3FeO4 (216 atoms). The 2 × 2 × 2 k-point meshes were adopted for all configurations, and the maximum kinetic energy and convergence criterion were the same as those in the electronic structure calculations.

To describe the three-phonon scattering processes, the anharmonic third-order atomic force constants must be evaluated. In this paper, the ShengBTE package66 was adopted to obtain the third-order IFCs and solve the Boltzmann transport equation (BTE). klatt at different temperatures can be calculated as the sum of contributions over all the phonon modes λ with branch p and wavevector q

where N is the number of uniformly spaced q points in the Brillouin zone, V is the volume of the unit cell, f is the Bose-Einstein distribution function depending on the phonon angular frequency \({\omega }_{\lambda }\), and \({v}_{\lambda }\,\)is the group velocity. The phonon lifetime \({\tau }_{\lambda }\) is equal to the inverse of the total scattering rate. For the calculation of third-order IFCs, interactions up to the ninth nearest neighbors were considered, and the supercells and other calculation details by VASP were the same as those in second-order harmonic IFCs. The q grids were tested from 9 × 9 × 9 to 16 × 16 × 16 in the ShengBTE code. Further increase in the q-mesh would change the calculated klatt by less than 1%. Therefore, well-converged 16 × 16 × 16 q-meshes were used for MgO and (Mg,Fe)O Fp.

Data Availability

The data for this paper are available from K.H. He (khhe@cug.edu.cn).

References

Badro, J. et al. Electronic transitions in perovskite: possible nonconvecting layers in the lower mantle. Science 305(5682), 383 (2004).

Badro, J. et al. Iron partitioning in Earth’smantle: Toward a deep lower mantle discontinuity. Science 300, 789–791 (2003).

Lin, J. F. et al. Spin transition of iron in magnesiowüstite in Earth’s lower mantle. Nature 436, 377–380 (2005).

Speziale, S. et al. Iron spin transition in Earth’s mantle. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 102, 17918–17922 (2005).

Kantor, I. Y., Dubrovinsky, L. S. & McCammon, C. A. Spin crossover in (Mg,Fe)O: A Mössbauer effect study with an alternative interpretation of X-ray emission spectroscopy data. Phys. Rev. B 73(R), 100101 (2006).

Kantor, I. et al. Short-range order of Fe and clustering in Mg1-xFexO under high pressure. Phys. Rev. B 80, 014204 (2009).

Sturhahn, W., Jackson, J. M. & Lin, J. F. The spin state of iron in minerals of Earth’s lower mantle. Geophys. Res. Lett. 32, L12307 (2005).

Tsuchiya, T., Wentzcovitch, R. M., da Silva, C. R. S. & de Gironcoli, S. Spin transition in magnesiowüstite in Earth’s lower mantle. Phys. Rev. Lett. 96, 198501 (2006).

Lin, J. F. et al. Spin transition zone in Earth’s lower mantle. Science 317, 1740–1743 (2007).

Wentzcovitch, R. M. et al. Anomalous compressibility of ferropericlase throughout the iron spin cross-over. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 106, 8447–8452 (2009).

Mao, Z., Lin, J. F., Liu, J. & Prakapenka, V. B. Thermal equation of state of lower-mantle ferropericlase across the spin crossover. Geophys. Res. Lett. 38, L23308 (2011).

McCammon, C. et al. Stable intermediate-spin ferrous iron in lower mantle perovskite. Nat. Geosci. 1, 684–687 (2008).

Narygina, O. V., Kantor, I. Y., McCammon, C. A. & Dubrovinsky, L. S. Electronic state of Fe2+ in (Mg,Fe)(Si,Al)O3 perovskite and (Mg,Fe)SiO3 majorite at pressures up to 81 GPa and temperatures up to 800 K. Phys. Chem. Miner. 37, 407–415 (2010).

Goncharov, A. F. et al. Effect of composition, structure, and spin state on the thermal conductivity of the Earth’s lower mantle. Phys. Earth Planet. Inter. 180(3–4), 148–153 (2010).

Lin, J., Speziale, S., Mao, Z. & Marquardt, H. Effects of the electronic spin transitions of iron in lower mantle minerals: implications for deep mantle geophysics and geochemistry. Rev. Geophy. 51(2), 244–275 (2013).

Lyubutin, I. S., Gavriliuk, A. G., Frolov, K. V., Lin, J. F. & Troyan, I. A. High-spin-low-spin transition in magnesiowüstite (Mg0.75,Fe0.25)O at high pressures under hydrostatic conditions. Jetp. Letters 90, 617–622 (2009).

Fei, Y. W. et al. Spin transtion and equations of state of (Mg,Fe)O solid solutions. Geophys. Res. Lett. 34, 1824–1827 (2007).

Crowhurst, J. C., Brown, J. M., Goncharov, A. F. & Jacobsen, S. D. Elasticity of (Mg,Fe)O through the spin transition of iron in the lower. Science 319, 451–453 (2008).

Muir, J. M. R. & Brodholt, J. P. Elasticity of (Mg,Fe)O through the spin elastic properties of ferropericlase at lower mantle conditions and its relevance to ULVZs. Earth. Planet. Sci. Lett. 417, 40–48 (2015).

Yang, J., Tong, X. Y., Lin, J. F., Okuchi, T. & Tomioka, N. Elasticity of ferropericlase across the spin crossover in the earth’s lower mantle. Sci. Rep. 5, 17188–17196 (2016).

Lin, J. F. & Tsuchiya, T. Spin transition of iron in the Earth’s lower mantle. Phys. Earth Planet. Inter. 170, 248–259 (2008).

Hsu, H., Umemoto, K., Blaha, P. & Wentzcovitch, R. M. Spin states and hyperfine interactions of iron in (Mg,Fe)SiO3 perovskite under pressure. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 294, 19–26 (2010).

Hsu, H., Blaha, P., Cococcioni, M. & Wentzcovitch, R. M. Spin-state crossover and hyperfine interactions of ferric iron in MgSiO3 perovskite. Phys. Res. Lett. 106, 118501 (2011).

Catalli, K. et al. Spin state of ferric iron in MgSiO3 perovskite and its effect on elastic properties. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 289, 68–75 (2010).

Catalli, K., Shim, S. H., Prakapenka, V. B., Zhao, J. & Sturhahn, W. X-ray diffraction and Mössbauer spectroscopy of Fe3+-bearing Mg-silicate post-perovskite at 128–138 GPa. Am. Mineral. 95, 418–421 (2010).

Kushwah, S. S. & Shanker, J. Analysis of thermal expansivity of periclase (MgO) at high temperatures. Physica. B 225, 283–287 (1996).

Sun, X. W. et al. Comparative investigations of the thermal expansivity of MgO at high temperature. Mater. Res. Bull. 44, 1729–1733 (2009).

Liu, Z. J., Tang, Y., Qi, J. H. & Wang, Z. L. Phonon dispersion curves and thermodynamic properties of MgO from first-principles calculations. J. Atom. Mol. phys. 22, 405–409 (2005).

Sushil, K. Volume dependence of isothermal bulk modulus and thermal expansivity of MgO. Physica. B 367, 114–223 (2005).

Dubrovinsky, L. S. & Saxena, S. K. Thermal expansion of periclase (MgO) and tungsten (W) to melting temperatures. Phys. Chem. Miner. 24, 547–550 (1997).

Fei, Y. W., Mao, H. K., Shu, J. F. & Hu, J. Z. P-V-T equation of state of magnesiowüstite (Mg0.6Fe0.4)O. Phys. Chem. Miner. 18, 416–422 (1996).

Wu, Z., Justo, J. F., Silva, C. R. S. D., Girnocoli, S. D. & Wentzcovitch, R. M. Publisher’s Note: Anomalous thermodynamic properties in ferropericlase throughout its spin crossover. Phys. Rev. B 80, 1132–1136 (2009).

Fukui, H., Tsuchiya, T. & Baron, A. Q. R. Lattice dynamics calculations for ferropericlase with internally consistent LDA + U method. J. Geophys. Res. 117, B12202 (2012).

Scanavino, I., Belousov, R. & Prencipe, M. Ab initio quantum-mechanical study of the effects of the inclusion of iron on thermoelastic and thermodynamic properties of periclase (MgO). Phys. Chem. Miner. 39, 649–663 (2012).

Scanavino, I. & Prencipe, M. Ab-initio determination of high-pressure and high-temperature thermoelastic and thermodynamic properties of low-spin (Mg1-xFex) O ferropericlase with x in the range [0.06, 0.59]. Am. Mineral. 98, 1270–1278 (2013).

Dekura, H. & Tsuchiya, T. Ab initio lattice thermal conductivity of MgO from a complete solution of the linearized boltzmann transport equation. Phys. Rev. B 95(18), 184303 (2017).

de Koker, N. Thermal conductivity of MgO periclase from equilibrium first principles molecular dynamics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 103(12), 125902 (2009).

de Koker, N. Thermal conductivity of MgO periclase at high pressure: implications for the D″ region. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 292(3), 392–398 (2010).

Dalton, D. A., Hsieh, W. P., Hohensee, G. T., Cahill, D. G. & Goncharov, A. F. Effect of mass disorder on the thermal conductivity of MgO periclase under pressure. Sci. Rep. 3, 2400 (2013).

Haigis, V., Salanne, M. & Jahn, S. Thermal conductivity of MgO, MgSiO3 perovskite and post-perovskite in the Earth’s deep mantle. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 355, 102–108 (2012).

Imada, S. et al. Measurements of thermal conductivity of MgO to core-mantle boundary pressures. Geophys. Res. Lett. 41(13), 4542–4547 (2014).

Tang, X. & Dong, J. Pressure dependence of harmonic and anharmonic lattice dynamics in MgO: a first-principles calculation and implications for thermal conductivity. Phys. Earth Planet. Inter. 174(1–4), 33–38 (2009).

Tang, X. & Dong, J. Lattice Thermal conductivity of MgO at conditions of earth’s interior. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 107(10), 4539–4543 (2010).

Stackhouse, S., Stixrude, L. & Karki, B. B. Thermal conductivity of periclase (MgO) from first principles. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104(104), 208501 (2010).

Stackhouse, S. & Stixrude, L. Theoretical methods for calculating the Lattice thermal conductivity of minerals. Rev. Mineral. Geochem. 71, 253–269 (2010).

Hofmeister, A. M. Pressure dependence of thermal transport properties. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 104, 9192–9197 (2007).

Katsura, T. Thermal diffusivity of periclase at high temperatures and high pressures. Phys. Earth Planet. Int. 101, 73–77 (1997).

Manthilake, G. M., de Koker, N., Dan, J. F. & Mccammon, C. A. Lattice Thermal conductivity of lower mantle minerals and heat flux from Earth’s core. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 108(44), 17901–17904 (2011).

Goncharov, A. F. et al. Experimental study of thermal conductivity at high pressures: implications for the deep earth’s interior. Phys. Earth Planet. Inter. 247, 11–16 (2015).

Ohta, K., Yagi, T., Hirose, K. & Ohishi, Y. Thermal conductivity of ferropericlase in the earth’s lower mantle. Earth. Planet. Sc. Lett. 465, 29–37 (2017).

Stackhouse, S., Stixrude, L. & Karki, B. B. First-principles calculations of the lattice thermal conductivity of the lower mantle. Earth. Planet. Sc. Lett. 427, 11–17 (2015).

Tsuchiya, T., Wentzcovitch, R. M., da Silva, C. R. S., de Gironcoli, S. & Tsuchiya, J. Pressure induced high spin to low spin transition in magnesiowüstite. Phys. Stat. Sol. (b) 243(9), 2111–2116 (2006).

Chopelas, A. Thermal expansion, heat capacity and entropy of MgO at mantle pressures. Phys. Chem. Miner. 17, 142–148 (1990).

Fei, Y. Thermal Expansion. AGU Reference Shelf, Washington, D. C. (1995).

Fiquet, G., Richet, P. & Lyon, A. D. High-temperature thermal expansion of lime, periclase, corundum and spinel. Phys. Chem. Miner. 2, 103–111 (1999).

Karki, B. B., Wentzcovitch, R. M., Gironcoli, S. & Baroni, S. High-pressure lattice dynamics and thermoelasticity of MgO. Phys. Rev. B 61, 8793–8800 (2000).

Touloukian, Y. S., Kirdby, R. K., Taylor, R. E. & Lee, T. Y. R. Thermophysical Properties of Matter (Plenum, New York), Vol. 13 (1977).

Westrenen, W. V. et al. Thermoelastic properties of (Mg0.64Fe0.36)O ferropericlase based on in situ X-ray diffraction to 26.7 GPa and 2173 K. Phys. Earth Planet. Inter. 151(1), 163–176 (2005).

Li, W. & Mingo, N. Thermal conductivity of fully filled skutterudites: role of the filler. Phys. Rev. B 89(18), 2096–2107 (2014).

Li, W. & Mingo, N. Lattice dynamics and thermal conductivity of skutterudites CoSb3 and IrSb3 from first principles: why IrSb3 is a better thermal conductor than CoSb3. Phys. Rev. B 90(9), 094302 (2014).

Kresse, G. & Furthmuller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169–11186 (1996).

Ceperley, D. M. & Alder, B. J. Ground State of the Electron Gas by a Stochastic Method. Phys. Rev. Lett. 45, 566–569 (1980).

Krukau, A. V., Vydrov, O. A., Izmaylov, A. F. & Scuseria, G. E. Influence of the exchange screening parameter on the performance of screened hybrid functionals. J. Chem. Phys. 125, 224106–224110 (2006).

Monkhorst, H. J. & Pack, J. D. Special points for Brillouin-zone integrations. Phys. Rev. B 13, 5188–5192 (1976).

Togo, A., Oba, F. & Tanaka, I. First-principles calculations of the ferroelastic transition between rutile-type and CaCl2-type SiO2 at high pressures. Phys. Rev. B 78, 134106 (2008).

Li, W., Carrete, J., Katcho, N. A. & Mingo, N. Shengbte: a solver of the boltzmann transport equation for phonons. Comput. Phys. Commun. 185(6), 1747–1758 (2014).

Acknowledgements

We appreciate Zhenmin Jin for helpful suggestions and discussions. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 41474067, 41402034) and the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (No. 2015M570670). The use of the computational resources of the China University of Geosciences (Wuhan) is also acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.H. and Y.S. conceived the research. Y.S., K.H., J.S. and C.M. performed the calculations. All authors analyzed the results. Y.S., K.H. and J.S. wrote the manuscript. M.W., Q.W. and Q.C. assisted in writing and revising the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Song, Y., He, K., Sun, J. et al. Effects of iron spin transition on the electronic structure, thermal expansivity and lattice thermal conductivity of ferropericlase: a first principles study. Sci Rep 9, 4172 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-40454-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-40454-4

This article is cited by

-

Lattice thermal conductivity of Mg2SiO4 olivine and its polymorphs under extreme conditions

Physics and Chemistry of Minerals (2023)

-

The influence of δ-(Al,Fe)OOH on seismic heterogeneities in Earth’s lower mantle

Scientific Reports (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.