Abstract

The base of glaciers and ice sheets provide environments suitable for the production of methane. High pressure conditions beneath the impermeable ‘cap’ of overlying ice promote entrapment of methane reserves that can be released to the atmosphere during ice thinning and meltwater evacuation. However, contemporary glaciers and ice sheets are rarely accounted for as methane contributors through field measurements. Here, we present direct field-based evidence of methane production and release from beneath the Icelandic glacier Sólheimajökull, where geothermal activity creates sub-oxic conditions suited to methane production and preservation along the meltwater flow path. Methane production at the glacier bed (48 tonnes per day, or 39 mM CH4 m−2 day−1), and evasion to the atmosphere from the proglacial stream (41 tonnes per day, or 32 M CH4 m−2 day−1) indicates considerable production and release to the atmosphere during the summer melt season. Isotopic signatures (−60.2‰ to −7.6‰ for δ13Cch4 and −324.3‰ to +161.1‰ for Dch4), support a biogenic signature within waters emerging from the subglacial environment. Temperate glacial methane production and release may thus be a significant and hitherto unresolved contributor of a potent greenhouse gas to the atmosphere.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The subglacial environment provides conditions suitable for the production and storage of methane. The presence of liquid water beneath temperate and polythermal ice masses, sub-oxic conditions due to poor hydrological connectivity, and carbon within basal sediments allow the survival of microbiological communities with the potential to produce biogenic methane eg.1,2,3. The source of carbon essential for fuelling microbiologically-mediated reactions can be generated either in-situ at the bed of the glacier through chemolithoautotrophic production4, through utilising organic containing fossil soils2,5,6,7, or sourced from the surface environment8. Geogenic subglacial methane comprises abiogenic sources from subglacial volcanism, geothermal activity, and thermogenic sources through the thermal degradation of organic matter and subsequent migration of methane from hydrocarbon reserves to a stable sub-ice storage location e.g.3,9. Methane present at the bed of glaciers and ice sheets can then be retained in situ by high overburden pressures and low temperatures, which promote the entrapment of gases, or the storage of methane in hydrate reserves. Vast methane reservoirs potentially containing hundreds of petagrams of carbon could therefore accumulate and, if released as the ice melts, contribute positive feedback to rising atmospheric greenhouse gas concentration and global temperature1,2,3.

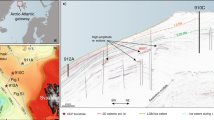

However, despite the presence of active microbial assemblages5,8,10 and favourable pressure–temperature relationships1,2,3 for methane production and storage in the subglacial realm, methane in glacial meltwaters has only been directly detected as aqueous methane in one study (albeit with limited sampling regime)11, or else inferred indirectly using δ13C of dissolved organic carbon12. For methane to be detected in meltwater outflow, sub-oxic conditions must occur not only at the glacier bed, but also throughout the subglacial drainage path. These conditions typically arise at the onset of subglacial discharge, during winter baseflow or as brief reversals in redox status of subglacial waters11,13,14,15,16,17,18. The inherently transient nature of these conditions thereby provides limited opportunity for direct field-based characterisation of methane production. Here, we examine an Icelandic glacier, Sólheimajökull, an outlet glacier of the Mýrdalsjökull icecap (Supplementary Fig. S1), where sub-oxia within the subglacial water column allows the transport of methane from beneath the ice mass and enables isotopic determination of methane formation mechanisms. The subglacial hydrological system of Sólheimajökull supports extensive sub-oxic conditions throughout the summer due to deep connectivity with the geothermal zone of the active, ice covered Katla volcanic system, where release of reduced gases consume oxygen in the meltwaters19. Sub-oxic summer discharge thereby preserves dissolved methane during transport from beneath the glacier. Here, we document the changing concentration and isotopic composition of methane contained within glacial waters across the 2013 to 2017 melt seasons in order to determine methane flux and mechanism of formation. Stable isotopic analysis of δ13Cch4 and Dch4 are used to provenance the methane between biogenic and geogenic sources, and incubation experiments are used to support field evidence for methane biogeochemical cycling. Whilst the specific environmental conditions at Sólheimajökull provide ideal opportunities to investigate mechanisms of methane formation and release dynamics, they also highlight the potential for methane production beneath contemporary glaciers worldwide, especially under a changing climate.

Results

Concentrations of methane present in the meltwater streams of Sólheimajökull between 2013 to 2017 are provided in Table 1. Greatest methane concentrations coincide with the location of meltwaters upwelling under pressure from the subglacial environment. Streams originating from external catchments and those of supraglacial source contain minimal levels of aqueous methane, with limited contribution to the total methane flux. Methane concentrations also vary on a seasonal basis, with greatest concentrations apparent following upwelling of subglacial meltwaters in the late melt season (Table 1). Field chamber-based experiments demonstrate minimal methane production and consumption from the proglacial sediments (Supplementary Table S1). Isotope signatures of δ13Cch4 and Dch4 measured in-situ in meltwaters from the 2014 field season have values ranging between −60.2‰ to −7.6‰ for δ13Cch4 and −324.3‰ to +161.1‰ for Dch4 (Fig. 1). At the point of subglacial upwelling, methane appears to be of predominantly microbial origin (δ13Cch4 < −50‰) and laboratory incubation of associated subglacial sediments demonstrate a strong potential for methanogenesis (methane production rates of 1.15 × 107 fmol CH4 g−1 h−1 at incubation temperatures of 15 °C; see Supplementary Fig. S2). Potential for methanotrophy within the subglacial sediments is also demonstrated through incubation of sediments under oxidising conditions (methane oxidation rates of 9.6 × 109 fmol CH4 g−1 h−1, at 15 °C, see Supplementary Fig. S2).

Carbon and hydrogen isotopic composition of methane in field data from Sólheimajökull, Iceland and in residual headspace gases during incubation of subglacial sediments under methanotrophic conditions. Bounded areas represent the typical range in methane isotopic composition of microbial and geogenic origin, modified from26. The similar relationship between δ13Cch4 and Dch4 in incubations and field data suggest the presence of methanotrophic activity within the field environment.

Discussion

The appearance of elevated aqueous methane concentrations that are commensurate with the location and onset of subglacial drainage, suggests the environment of methane production must be beneath the glacier. Fluctuating discharge and changing subglacial methane concentrations on a seasonal basis preclude straightforward calculation of an annual methane flux from beneath the glacier. However, a typical summer season discharge of 50 m3 s−1 from the meltwater outlet stream Jökulsá á Sólheimasandi20, and the corresponding average aqueous methane concentration of 11.2 mg l−1 (Table 1) can be used to estimate a flux of 48 Tonnes per day of methane transported away from the ice margin. This high flux occurs as meltwater exits the ice-marginal proglacial lake after the onset of discharge from the subglacial drainage system. When calculated as a day-rate per m2 ice-covered area (maximum 78 km2 glaciated catchment area cf.21) this equates to a subglacial production capacity of 39 mM CH4 m−2 day−1. Using an upstream – downstream mass balance along the 4 km length (20 m width) of proglacial meltwater channel (taken as the difference in methane concentration between the meltwater outlet sampling site and the catchment outlet at the N1 road bridge, supplementary Fig. S1), evasion to the atmosphere was calculated as 86%. This equated to an evasive flux of 41 tonnes of methane to the atmosphere per day (32 M CH4 m−2 day−1 as an area-weighted flux from stream to atmosphere). This mass balance approach to calculating an evasive methane flux along the stream assumes minimal dilution, and no in-stream methanotrophy. Both are valid assumptions given the minimal input of additional meltwater between upstream and downstream sampling points, the minimal production/consumption of methane in the proglacial sediments (Table S1), and the limited change in isotopic composition of aqueous methane (Table 1). The onset of upwelling subglacial water varies on an annual basis at all glaciers, dependent on antecedent conditions. Prior to the upwelling of subglacial meltwaters during the 2014 sampling season (day of year 128), a more conservative flux of methane transported away from the ice margin is estimated as 0.6 tonnes per day (equivalent to 0.5 mM CH4 m−2 day−1, based on an average winter discharge of 10 m3 s−1 and mean methane concentration of 0.65 mg l−1). Evasion to the atmosphere was calculated as 54% along the 4 km stream reach, equating to 0.25 M CH4 m−2 day−1. Methane evasion from the Sólheimajökull sub-aerial stream network greatly exceeds mean flux values between river to atmosphere reported in the literature (4.23+\−8.41 mM CH4 m−2 day−1)22 indicating the potential significance of the subglacial methane source, if similar processes are also occurring at other glaciers.

The origin of the methane can be inferred through stable isotopic analysis of δ13Cch4 and Dch4. Isotopic fractionation during biogenic methanogenesis typically leads to δ13C values between −50 to −110‰, and δD values between −170 to −531‰23. Geogenic methane produced at high geothermal temperatures undergoes exchange with the surrounding water and mantle carbon, producing deuterium and carbon contents enriched in 2H and 13C respectively24. Signatures of mixed geogenic/microbial origin should therefore lie on an end member mixing trajectory as depicted in Fig. 1, with microbially-sourced methane clearly emanating from the point of subglacial upwelling. However, possible alteration to methane signatures by methanotrophic activity (methane oxidation) will enrich the remaining pool of methane reactants in 13C and deuterium. As the most enriched values exceed the geogenic range, the observed isotopic signatures cannot be explained by a mixture of biogenic and geogenic methane (Fig. 1). Extensive potential for methanotrophic activity, as evidenced through the incubation of sediments under oxidizing conditions (see Supplementary Fig. S2), likely explains the isotopic fractionation trajectory away from the microbial end member signature. Fractionation between the starting methane isotopic composition (CH4(i)) and composition of residual methane (CH4(t)) is quantified following25 as α = 1.019 for 13C/12C, and for fractionation of D/H as α = 1.197. These incubation determined values of C and H enrichment during methanotrophy are encompassed within the published range of experimental values23, and result in relative changes to isotopic signatures during reaction progress that lie on a similar gradient to field data from this study (Fig. 1 and methods). This isotope signature confirms that methane emanating from the subglacial environment of Sólheimajökull is predominantly regulated by microbial activity.

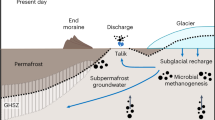

The important role played by microbial activity in determining this remarkably high methane flux from beneath Sólheimajökull is surprising given the extensive geothermal activity beneath the Mýrdalsjökull icecap26. However, based on isotopic evidence, subglacial geothermal activity appears not to contribute to the methane flux. Instead, we consider the subglacial geothermal activity to be instrumental only in driving the summer subglacial discharge to low redox status, allowing preservation and transport of microbially-generated, dissolved methane to the point of upwelling without oxidation to CO2. Most temperate glacial drainage systems which do not overlie volcanic and/or geothermal systems are characterised by a slow flow winter component in which subglacial water is confined to linked cavities, basal film flow and/or water saturated till, dependent upon the state of the glacier bed (hard- or soft-based). Under these conditions of distributed drainage (the ‘closed’ system), connectivity to the atmosphere is poor and dissolved gases can be depleted to produce meltwaters of low redox status. During the summer season, a discrete well-connected subglacial drainage system, characterised by well-defined conduits, expands up-glacier dependent upon the flux of surface run-off to the glacier bed, and typically follows the supraglacial snowline. Within this ‘open’ configuration, oxygen saturated meltwaters can drain rapidly from the surface of the glacier and through the subglacial system27,28. At polar glaciers of a polythermal nature, the drainage system displays similar characteristics, albeit with the winter slow flow component of the drainage system remaining sealed beneath the glacier until basal water pressures force a pressurised outflow, either shortly after the onset of the summer season29, or intermittently throughout the winter to produce characteristic proglacial icings e.g.30. However, at Sólheimajökull, the presence of the Katla geothermal area beneath the head of the glacier imparts profoundly different characteristics to meltwater discharge (Fig. 2). During the summer season (Fig. 2a), headward expansion of the conduit drainage system proceeds in the conventional fashion based on an enhanced flux of meltwater between glacier surface and bed. When the conduit drainage system connects with the zone of geothermal activity, release of reduced gases into the drainage system produces the characteristic volatile-rich, oxygen-depleted chemical composition of the discharge, as evidenced by the hydrogen sulphide content and sulphur isotopic composition of the meltwaters19. The summer season sub-oxic meltwater arguably inhibits methanotrophic activity beneath the glacier, allowing the preservation of dissolved biogenic methane until the point of upwelling and contact with the atmosphere. The transported methane comprises methane formed during the winter ‘closed’ system phase (zero-flux scenario3), together with methane produced during the summer season. During the winter season (Fig. 2b), the conduit drainage system is restricted to the lower elevations of the glacier, where year-round ablation maintains a conduit configuration connected to the atmosphere and isolated from the Katla geothermal zone. Under this configuration, methane production is limited and methanotrophic activity minimises the methane flux.

Schematic model of hydrological evolution at Sólheimajökull, Iceland. The headward expansion of the conduit drainage system intersects with the geothermal area, where release of reduced gases determines the sub-oxic meltwater status essential for preserving aqueous methane until the point of emergence from beneath the glacier. (a) Summer season snowpack ablation delivers meltwater to expand the conduit drainage system headwards into the Katla geothermal field. This results in a drainage system well-connected to deep within the geothermal field, delivering water of reducing status. Methane generated within the basal sediments through microbial methanogenesis is preserved during export. (b) Winter season limited surface ablation restricts the conduit drainage system to the lower reaches of the glacier. This results in a drainage system operating close to atmospheric conditions within the vicinity of the glacier snout and poorly connected to deeper beneath the ice mass. Much of the methane generated within the surrounding sediments is oxidised proximal to the channelized drainage system before being exported from beneath the glacier.

The geothermally-influenced nature of the Sólheimajökull system is unusual in its ability to present a low redox status window which inhibits methane oxidation and preserves aqueous methane until the point of release from beneath the glacier. The dominance of biogenic methane production beneath an Icelandic temperate ice mass nonetheless raises the distinct possibility that methane generation could be proceeding undetected in other subglacial environments where the cocktail of temperate ice, low oxygen concentration, organic carbon and methanogenic communities coincide to promote methanogenesis. Increasing evidence for zones of strong geothermal activity beneath the West Antarctic Ice Sheet suggests that subglacial microbial communities with methanogenic potential may be more significant and extensive than previously anticipated31,32. However, cold ice barriers and the length of meltwater pathways to ice termini means methane is typically trapped beneath ice masses, or oxidised during subglacial transit away from its zone of production. This prevents confident extrapolation of the subglacial methane production at Sólheimajökull to other regions, or to a global scale. Thus, the relative contribution of subglacial methane to global atmospheric fluxes critically depends on the extent of sub-oxic ‘windows’ at temperate and polythermal basal ice systems. We suggest that, in order to identify subglacial methane fluxes from temperate and polythermal glacial systems, and better constrain any associated climatic impact, the quest for quantifying methane release dynamics should focus on these sub-oxic windows of meltwater discharge. This may include studying other ice masses with elevated geothermal heat fluxes; characterising baseflow seepage and initial fractions of summer subglacial discharge at both temperate and polythermal glaciers; and analysing gases trapped within proglacial icings. Under a changing climate with accelerated ice thinning33, enhanced overburden pressure release on subglacial volcanic and geothermal systems is likely to drive an increase in eruptive activity34. Anomalous heat fluxes are known to both precede and follow volcanic activity, likely due to pressure-induced boiling in geothermal systems35. Release of reduced gases during this enhanced geothermal activity would determine the prevalence of sub-oxic windows (and methane content) of meltwater discharge. Greater headward expansion of drainage systems towards geothermal areas currently isolated beneath ice mass overburden would also ensure transport of meltwater and associated methane content to a position of sub-aerial degassing into the atmosphere. Pressure driven sub-oxia would likely become more prevalent with ice thinning until overwhelmed by the flux of oxygenated surface melt reaching the glacier bed or until ice disappearance. In this manner, this poorly quantified flux of sub-ice cap methane is likely an indirect, albeit self-reinforcing consequence of climatic change.

Methods

Sample collection

Field samples were collected over restricted periods within the melt seasons of 2013 to 2017. Precise collection intervals are depicted in Table 1, with the 2014 collection period noted to cover both pre- and post-emergence of subglacial upwelling meltwaters. As far as the evolving nature of the proglacial system allowed, sample collection sites remained at consistent locations throughout both summer seasons. Sampling locations for aqueous methane comprised supraglacial streams, subglacial upwellings located at the frontal ice margin, and proglacial waters sampled at sites flanking the eastern and western edges of the ice marginal proglacial lake, and as mixed meltwaters in the outlet stream, Jökulsá á Sólheimasandi. Streams of external catchment origin were sampled as control sites to verify methane as specific to the Sólheimajökull catchment. Repeat samples were collected at each location throughout the period of monitoring.

Samples for the determination of aqueous methane concentration were collected as a known volume of unfiltered water and stored within an airtight chamber with headspace at atmospheric pressure. Samples were left for 24 hours to undergo headspace equilibration and gases were then extracted through a sampling port and injected into evacuated exetainers (Labco Ltd, UK) for later analysis of methane concentration and isotopic determination. Exetainers were over-pressurised to prevent ingress of atmospheric air and stored at ambient temperature to prevent vessel contraction and leakage. Headspace gas extraction at time t = 0 was used to determine background concentration prior to sample equilibration.

Proglacial sediments were monitored for the production and consumption of methane (methanogenesis and methanotrophy respectively) using static chambers (15 cm diameter × 10 cm height). Chambers were inserted into the sediments in triplicate at each site, and covered in aluminium foil to minimise temperature changes during the sampling period. Headspace gases were removed at set time intervals over a 45 minute incubation period to monitor the rate of methane production/consumption. Headspace gases were injected into evacuated exetainers which were over-pressurised to prevent the ingress of atmospheric air and stored at ambient temperature prior to further analysis for methane concentration. Flux values were calculated as µM CH4 m−2 day−1 following36.

Incubation procedure

Sediments extruded onto the glacier surface via thrust planes or melt out of fracture fill deposits c.f.37 were deemed the closest analogue to typical subglacial sedimentary deposits from the Sólheimajökull catchment. Sediments were incubated to determine the potential for methane production (methanogenesis) and consumption (methanotrophy) using standard procedures38. For each incubation type 10 grams of fresh weight sediment was added to a 100 ml sterilised Wheaton bottle and slurried with 20 ml deionised water. For anaerobic methane production incubations, the headspace was flushed with nitrogen gas to eliminate oxygen. For aerobic incubations the headspace was flushed with synthetic air, following which the methane concentration was adjusted to 150 ppm methane to assay for methanotrophy. Each set of incubations operated alongside control chambers supporting identical headspace conditions, but without the inclusion of sediment. All incubations were undertaken at a set temperature of 15 °C, reflecting optimal conditions for methane production and consumption, as established through preliminary testing. For methane production and oxidation potentials, triplicate samples were incubated for 49 and 7 days, respectively with regular sampling intervals during the periods of incubation (Supplementary Fig. S2). At the time of sampling 1 ml was withdrawn from the headspace and directly injected into the GC (see below for details of analysis). Rates of methanotrophy and methanogenesis were calculated based on a production potential per day, per gram (dry weight) of sediment. Samples for δ13C and δD analysis were withdrawn from the incubation chamber headspace and injected into pre-evacuated 3 ml exetainers (see below for details of isotopic analysis). Fractionation between starting methane isotopic composition (CH4(i)) and composition of residual methane (CH4(t)) in the closed headspace is calculated following25:

Where f is the fraction of methane remaining and δX is the isotopic composition of methane.

Laboratory Chemical analysis

Methane concentrations were analysed using a PerkinElmer Autosystem XL Gas Chromatograph (GC) (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA) fitted with a Flame Ionisation Detector (FID) operating at 300 °C. The GC was fitted with a stainless steel Porapak Q 50–80 mesh column (length 2 m, outer diameter 3.17 mm) maintained at 60 °C. Three calibration gas standards (1, 10, 500 ppm CH4) (Air Products, Waltham on Thames, UK) were analysed in every analytical sequence to encompass the expected sample concentrations. Standards were repeated at regular intervals39 to check for drift and ensure accuracy to within 95% of the true value. Sample triplicates had a precision (1S.D) representing <0.2% of the average value. The concentration of methane in water (Caq) is related to the concentration of gas measured in the headspace (Cg) via the dimensionless Henry’s Law solubility Constant (HCC) at a temperature of 273 K (0 °C)40.

13C/12C and D/H ratios of headspace methane gas were determined by online combustion/pyrolysis respectively, followed by analysis using continuous flow isotope ratio mass spectrometry. For determination of δ13Cch4, headspace gases were injected manually into an Isoprime Trace gas analyser coupled to an Isoprime continuous flow isotope ratio mass spectrometer (Elementar UK, Stockport) at the NERC Life Sciences Mass Spectrometer Facility, CEH Lancaster, UK. Manual injection volumes were dependent upon methane concentration and did not exceed 10 ml. Samples were initially passed through a Magnesium perchlorate/Carbosorb scrubber trap at 20 ml/min to eliminate water and CO2. Methane is oxidised in a combustion furnace using a braided platinum/copper/nichrome furnace wire inside a ceramic furnace tube of 200 mm × 0.4 mm i.d. heated in a furnace at 960 °C41. A preparation flow rate of 10 psi was required to give a flow rate of 20 ml/min through the furnace at full operating temperature. For δDch4, gas samples were purged from vials using a dual core needle and Helium carrier gas into a ThermoScientific precon concentration unit interfaced to a ThermoScientific Delta V plus isotope ratio mass spectrometer at UC Davies, University of California, USA. Cryogenic trapping and GC separation followed by pyrolysis at 1450 °C yielded H2 for determination of D/H ratios of methane gas42. δ13C values were corrected to VPDB using working CH4 standards cross calibrated with a CO2 reference gas, calibrated to NIST REF-Heavy Palaeomarine Origin (CO2) (RM 8562) and NIST REF-Biogenic Modern Biomass Origin (CO2) (RM 8564). The reproducibility of δ13Cch4 was better than ±0.2‰. δD was corrected to VSMOW using reference gasses calibrated to international standards NIST 8559, 8560, and 8561. Within-run standard replication of both samples and standards (1SD) was better than 2.6‰ for Hydrogen.

Data Availability Statement

The underlying data pertaining to the figures and tables within this manuscript is available from https://doi.org/10.17635/lancaster/researchdata/246.

References

Weitemeyer, K. A. & Buffet, B. A. Accumulation and release of methane from clathrates below the Laurentide and Cordilleran ice sheets, Global and Planet. Change 53, 176–187 (2006).

Wadham, J. L., Tranter, M., Tulaczyk, S. & Sharp, M. Subglacial methanogenesis: a potential climatic amplifier? Global Biogeochem. Cy. 22(2) (2008).

Wadham, J. L. et al. Potential Methane Reservoirs Beneath Antarctica. Nature 488, 633–637 (2012).

Boyd, E. S., Hamilton, T. L., Havig, J. R., Skidmore, M. L. & Shock, E. L. Chemolithotrophic primary production in a subglacial ecosystem. Appl. Environ. Microb. 80(19), 6146–6153 (2014).

Punkari, M. & Forsstrom, L. Organic Remains in Finnish Subglacial Sediments. Quaternary Res. 43, 414–425 (1995).

Zeng, N. Glacial-interglacial atmospheric CO2 change—The glacial burial hypothesis. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 20(5), 677–693 (2003).

Zeng, N. Quasi-100 ky glacial-interglacial cycles triggered by subglacial burial carbon release. Clim. Past. 3, 135–153 (2007).

Stibal, M., Hasan, F., Wadham, J. L., Sharp, M. J. & Anesio, A. M. Prokaryotic Diversity in Sediments Beneath two Polar Glaciers with Contrasting Organic Carbon Substrates. Extremophiles 16, 255–265 (2012).

Anthony, K. M. W., Anthony, P., Grosse, G. & Chanton, J. Geologic methane seeps along boundaries of Arctic permafrost and melting glaciers. Nat. Geosci. 5, 419–426 (2012).

Boyd, E. S., Skidmore, M., Mitchell, A. C., Bakermands, C. & Peters, J. W. Methanogenesis in Subglacial Sediments. Env. Microbiol. Rep. 2(5), 685–692 (2010).

Dieser, M. et al. Molecular and biogeochemical evidence for methane cycling beneath the western margin of the Greenland Ice Sheet. ISME J. 8(11), 2305–2316 (2014).

Hindshaw, R. S. et al. Origin and temporal variability of unusually low δ13C-DOC values in two High Arctic catchments. Journal of Geophysical Research: Biogeosciences 121, 1073–1085 (2016).

Brown, G. H. et al. Dissolved Oxygen Variations in Alpine Glacial meltwaters. Earth Surf. Proc. and Land. 19, 247–253 (1994).

Tranter, M., Brown, G. H., Hodson, A., Gurnell, A. M. & Sharp, M. J. Variations in the nitrate concentration of glacial runoff in Alpine and sub-polar environments. IAHS-AISH P. 223, 299–311 (1994).

Bottrell, S. H. & Tranter, M. Sulphide oxidation under partly anoxic conditions at the bed of Haut Glacier D’Arolla, Switzerland. Hydrol. Process. 16(5), 959–993 (2002).

Wynn, P. M., Hodson, A. & Heaton, T. Chemical and isotopic switching within the subglacial environment of a High Arctic glacier. Biogeochemistry 78, 173–193 (2006).

Wynn, P. M., Hodson, A. J., Heaton, T. H. E. & Chenery, S. Nitrate production beneath a High Arctic Glacier. Chem. Geol. 244, 88–102 (2007).

Irvine-Fynn, T. D. L. & Hodson, A. J. Biogeochemistry and Dissolved Oxygen Dynamics at a Subglacial upwelling, Midtre Lovenbreen, Svalbard. Ann. of Glaciol. 51(56), 41–46 (2010).

Wynn, P. M. et al. Seasonal Release of Anoxic Geothermal Meltwater from the Katla Volcanic System at Sόlheimajökull, Iceland. Chem. Geol. 396, 228–238 (2015).

Lawler, D. M., McGregor, G. R. & Phillips, I. D. Influence of atmospheric circulation changes and regional climate variability on river flow and suspended sediment fluxes in southern Iceland. Hydrol. Process. 17, 3195–3223 (2003).

Lawler, D. M., Björnsson, H. & Dolan, M. Impact of subglacial geothermal activity on meltwater quality in the Jökulsa a Sólheimasandi system, Southern Iceland. Hydrol. Process. 10, 557–578 (1996).

Stanley, E. H. et al. The ecology of methane in streams and rivers: patterns, controls, and global significance. Ecol. Monogr. 86(2), 146–171 (2016).

Whiticar, M. J. Carbon and hydrogen isotope systematics of bacterial formation and oxidation of methane. Chem. Geol. 161, 291–314 (1999).

Etiope, G. & Sherwood Lollar, B. Abiotic methane on Earth. Rev. of Geophys. 51(2), 276–299 (2013).

Coleman, D. D. & Risatti, J. B. Fractionation of carbon and hydrogen isotopes by methane-oxidising bacteria. Geochim. Cosmochim. Ac. 45, 1033–1037 (1981).

Guðmundsson, M. T., Höganadóttir, P., Kristinsson, A. B. & Guðbjörnsson, S. Geothermal activity in the subglacial Katla caldera, Iceland, 1999 – 2005, studied with radar altimetry. Ann. of Glaciol. 45, 66–72 (2007).

Fountain, A. G. & Walder, J. S. Water Flow through Temperate Glaciers. Rev. of Geophys. 36(3), 299–328 (1998).

Flowers, G. E., Björnsson, H. & Pálsson, F. New insights into the subglacial and periglacial hydrology of Vatnajokull, Iceland, from a distributed physical model. J. Glaciol. 49(165), 257–270 (2003).

Irvine-Fynn, T. D. L., Hodson, A. J., Moorman, B. J., Vatne, G. & Hubbard, A. L. Polythermal Glacier hydrology: A Review. Rev. of Geophys. 49, 1–37 (2011).

Stachnik, Ł., Yde, J. C., Kondracka, M., Ignatiuk, D. & Grzesik, M. Glacier naled evolution and relation to the subglacial drainage system based on water chemistry and GPR surveys (Werenskioldbreen, SW. Svalbard). Ann. of Glaciol. 57(72), 19–30 (2016).

Schroeder, D. M. et al. Evidence for elevated and spatially variable geothermal flux beneath the West Antarctic Ice Sheet. P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 111, 9070–9072 (2014).

Fisher, A. T. et al. High geothermal heat flux measured below the West Antarctic Ice Sheet. Sci. Adv. 1(6), https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.1500093 (2015).

Pritchard, H. D., Arthern, R. J., Vaughan, D. G. & Edwards, L. A. Extensive dynamic thinning on the margins of the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets. Nature 461, 971–975 (2009).

Tuffen, H. How will melting of ice affect volcanic hazards in the twenty-first century? Philos. T. Roy. Soc. A. 368(1919), 2535–2558 (2010).

Reynolds, H. I., Gudmundsson, M. T., Högnadóttir, T. & Pálsson, F. Thermal power of Grímsvótn, Iceland, from 1998–2016: Quantifying the effects of volcanic activity and geothermal anomalies. J. Volcanol. Geoth. Res. 358, 184–193 (2018).

Holland, E. A. et al. Soil CO2, N2O and CH4 exchange. In: Standard soil methods for ecological research (eds Robertson, G. P., Coleman, D. C., Bledsoe, C. S. & Sollins, P.) 185–201 (Oxford University Press, New York, 1999).

Roberts, M. J., Russell, A. J., Tweed, F. S. & Knudsen, Ó. Ice fracturing during jökulhlaups: implications for englacial floodwater routing and outlet development. Earth Surf. Processes 25, 1429–1446 (2000).

Reay, D. S., Nedwell, D. B. & McNamara, N. Physical Determinants of Methane Oxidation Capacity in a Temperate Soil. Water Air Soil Poll. Focus 1(5-6), 401–414 (2001).

Case, S. D. C., McNamara, N. P., Reay, D. S. & Whitaker, J. The effect of biochar addition on N2O and CO2 emissions from a sandy loam soil–The role of soil aeration. Soil Biol. Biochem. 51, 125–134 (2012).

Sander, R. Compilation of Henry’s law constants (version 4.0) for water as solvent. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 15(8), 4399–4981 (2015).

Fisher, R., Lowry, D., Wilkin, O., Sriskantharajah, S. & Nisbet, E. G. High-precision, automated stable isotope analysis of atmospheric methane and carbon dioxide using continuous-flow isotope-ratio mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun Mass Sp. 20, 200–208 (2006).

Yarns, C. δ13C and δ2H measurement of methane from ecological and geological sources by gas chromatography/combustion/pyrolysis isotope-ratio mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun Mass Sp. 27, 1036–1044 (2013).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the European Regional Development Fund, Centre for Global Eco-Innovation (Grant Reference X02646PR) in collaboration with Elementar UK Ltd. H Tuffen is supported by a Royal Society University Research Fellowship. Funding was also received from the Natural Environment Research Council Life Sciences Mass Spectrometry Facility (Grant CEH/L/075/11/2013) for analysis of methane carbon isotopes. MJ Whiticar is thanked for the provision of dual isotope information forming the background to Fig. 1. We are grateful for the permissions granted from the Icelandic authorities to undertake this work, and especially to landowner Tómas ĺsleiffsson for allowing access to the field site.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Field data were collected by R.B., P.M.W., A.C., M.S., H.T. and S.O. Isotope analysis was undertaken A.S. and R.B. Geochemical analyses of methane concentration were conducted by R.B. and S.O. Laboratory experiments were designed and conducted by R.B., A.C., N.Mc.N., S.O. and N.O. The manuscript and figures were drafted by P.M.W. and R.B., with contributions from all authors, specifically including advice on carbon cycling from P.B., glacier hydrology from F.S.T. and methane isotope geochemistry from Z.Z.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Burns, R., Wynn, P.M., Barker, P. et al. Direct isotopic evidence of biogenic methane production and efflux from beneath a temperate glacier. Sci Rep 8, 17118 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-35253-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-35253-2

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Groundwater springs formed during glacial retreat are a large source of methane in the high Arctic

Nature Geoscience (2023)

-

Methylotrophic Communities Associated with a Greenland Ice Sheet Methane Release Hotspot

Microbial Ecology (2023)

-

Methane beneath Greenland’s ice sheet is being released

Nature (2019)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.