Abstract

Ocean warming (OW), ocean acidification (OA) and their interaction with local drivers, e.g., copper pollution, may negatively affect macroalgae and their microscopic life stages. We evaluated meiospore development of the kelps Macrocystis pyrifera and Undaria pinnatifida exposed to a factorial combination of current and 2100-predicted temperature (12 and 16 °C, respectively), pH (8.16 and 7.65, respectively), and two copper levels (no-added-copper and species-specific germination Cu-EC50). Meiospore germination for both species declined by 5–18% under OA and ambient temperature/OA conditions, irrespective of copper exposure. Germling growth rate declined by >40%·day−1, and gametophyte development was inhibited under Cu-EC50 exposure, compared to the no-added-copper treatment, irrespective of pH and temperature. Following the removal of copper and 9-day recovery under respective pH and temperature treatments, germling growth rates increased by 8–18%·day−1. The exception was U. pinnatifida under OW/OA, where growth rate remained at 10%·day−1 before and after copper exposure. Copper-binding ligand concentrations were higher in copper-exposed cultures of both species, suggesting that ligands may act as a defence mechanism of kelp early life stages against copper toxicity. Our study demonstrated that copper pollution is more important than global climate drivers in controlling meiospore development in kelps as it disrupts the completion of their life cycle.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The global climate is projected to change during the twenty-first century due mainly to anthropogenic combustion of fossil fuels and changes in land use1. In the marine environment, the projected future scenario includes a 4 °C increase in sea surface temperature and a reduction in pH from the current average of 8.10 to 7.74, phenomena known as ocean warming (OW) and ocean acidification (OA), respectively1. In addition, the hydrolysis of CO2 in seawater is increasing the concentration of H+, CO2, HCO3−, and decreasing the CO32− concentration2. However, the future scenario of OW and OA is not occurring in isolation from other anthropogenic activities that also threaten coastal environments at local levels3. For instance, in coastal environments, natural concentrations of copper (Cu2+) are low, but they are increasing due to human industrialization4. At high concentrations, copper becomes toxic, affecting metabolic processes of marine organisms. For example, >0.08 µM Cu negatively affect the completion of different life stages of brown macroalgae (species in the Order Fucales and Laminariales)5. The speciation and bioavailability of copper in seawater is highly dependent on seawater chemistry6,7. Metals such as Cu2+ can form inorganic complexes with CO32−, OH−, and Cl− 6,7, and organic complexes with organic ligands (L) such as thiols, exopolysaccharides and humic substances8,9. OA will reduce seawater CO32− concentrations and thus the stability of reaction constants in the formation of organic complexes: the toxic free ionic form of copper (i.e., speciation of Cu2+) in the oceans is thus predicted to increase by >50% by the end of the current century6. These changes in seawater chemistry have the potential to affect the physiological processes of marine organisms including macroalgae.

Coastal ecosystems from mid-latitudes to polar regions experience seasonal variations in environmental factors, including temperature and pH10, which are beyond the predictions by 2100 for the global ocean11. For example, daytime coastal seawater temperature can vary between 2–7 °C12,13 while diurnal seawater pH can vary by >1 unit due to macroalgal metabolism14,15. On the other hand, natural concentrations of copper in coastal seawater are generally low (0.008 and 0.050 µM)16, local human activities such as the production of industrial and domestic wastes, agricultural practices, copper mine drainage and usage of copper containing marine anti-fouling paint can result in local increases in copper concentrations above 3.0 µM4,17,18. Copper is an essential trace element for some biological functions in macroalgal physiology. For example, it forms part of the plastocyanin protein involved in photosynthetic electron transport and is a cofactor of the enzymes Cu/Zn-superoxide dismutase, cytochrome c oxidase, ascorbate oxidase, amino oxidase and polyphenol oxidase. However, at elevated concentrations, copper can be toxic to macroalgae and also a to a wide range of other marine organisms4,19,20.

Many organisms, including photosynthetic ones, can counteract the negative effects of high copper concentrations by the production of L4,21,22,23,24,25. L bind Cu, reducing its free ionic form (Cu2+) and weakly bound labile copper (Cu’) concentrations and thereby its toxicity. Thus, in a medium with an excess of copper, cells can transport the non-toxic ligand-bound copper (CuL) into or out of the cell across the plasma membrane for using or detoxifying copper, respectively4. The concentration and stability constants of L in solution (in seawater and culture media) can be indirectly determined by complexometric titration with copper26 or by using a kinetic approach27,28. In both cases, anodic or cathodic stripping voltammetry (ASV and CSV, respectively) are used as the detection method. The inorganic and labile organic complexes of copper (Cu’), measured using these voltammetric techniques, are considered bioavailable for biota, including macroalgae26. However, the structure of the L produced by macro- and microalgae are largely unknown21,26.

The life cycle of macroalgae consists of alternate microscopic and macroscopic stages. In kelps, microscopic meiospores (haploid spores resulting from meiosis) settle and develop into either male or female gametophytes. After fertilization, a diploid embryo is formed which grows to form the macroscopic adult29. Early life history stages of marine organisms are generally more sensitive to abiotic stress than their adult phase30,31 but studies on the effects of climate change on the microscopic phases of macroalgae are scarce2,32,33. The synergistic and additive toxic effects of copper under OA on early life stages of some marine invertebrates have been previously studied34,35. However, although macroalgal microscopic stages are highly sensitive to copper and hence have been widely used for ecotoxicity research5,36, the toxic effects of copper under increased temperature and/or OA conditions on early life stages have not been investigated.

Previous studies have shown that the independent and interactive effects of OA (pH 7.65) and OW (+4 °C) have little effect on the ontogenetic development of kelp meiospores32,33. This means that the completion of the life cycle from meiospore germination to sexual differentiation, and sexual reproduction to produce the next generation of adult sporophytes37 is unlikely to be compromised. Conversely, copper as a local environmental stressor was found to arrest sexual differentiation5, thus disrupting the completion of the life cycle. In this study, the interactive effects of seawater temperature (12 °C and 16 °C), pHT (8.16 and 7.65) and copper pollution on the ontogenic development of meiospores of the native M. pyrifera and the invasive U. pinnatifida, from south-eastern New Zealand, were studied. The nominal copper concentrations used in this experiment correspond to the species-specific Cu-EC50 for meiospore germination of M. pyrifera (2.47 µM CuT = 157 µg L−1 CuT) and U. pinnatifida (3.63 µM CuT = 231 µg L−1 CuT)5. We hypothesized that the negative effect of copper on meiospore development (i.e., germination, germling growth, gametophyte production and sexual differentiation) will be greater under future climate change scenarios (e.g., Cu × OA, Cu × OW, and Cu × OA × OW). However, production of L may alleviate any negative effects of copper on meiospore development. Moreover, the capacity of germlings and gametophytes to recover from local environmental drivers by removing the copper treatment after 9 days was investigated under each climate change scenario for a further 9 days. This is the first study on the interactive effects of global climate change drivers (OA and OW) and a local driver (metal pollution) on the early life history stages of key marine forest-forming species, and their capacity to recover from local environmental pollution.

Results

Meiospore germination

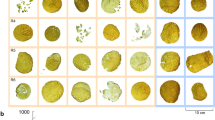

After 6 days, the percentage of germinated meiospores (i.e., with visible germ tube, Fig. 1) was calculated for both species. OA and OW had no significant effect on the germination of meiospores of both M. pyrifera and U. pinnatifida (germination >85%) (Fig. 2). A significant (P < 0.001) detrimental effect of copper (i.e., 5–18% reduction) on germination of meiospores of both species was observed in all treatment combinations, except under ambient temperature and current pH (Fig. 2). The greatest (P < 0.05, Tukey test) additional effect of copper in the reduction of germination was observed at current pH and OW in U. pinnatifida (18%) (Fig. 2b).

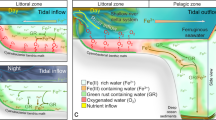

Summary of the main results of the current experiment (inner square). Dialogue boxes indicate the main effects of ocean warming (OW), ocean acidification (OA) and copper pollution (Cu-EC50) treatments on meiospore germination, germling growth rate and gametophyte development of M. pyrifera and U. pinnatifida (Order Laminariales). Left-right arrow (↔) indicates neutral effects, inclined arrow (↗) indicates slightly positive effects, downward arrow (↓) indicates negative effects (the thickness of only ↓ represents the magnitude of effects) and circle-backslash symbol (⦸) indicates that gametogenesis was inhibited. AN, antheridia; GR, germling; GT, germination tube; JS, juvenile sporophyte; MS, swimming meiospore; MS’, settled meiospore; MS”, germinated meiospore; OG, oogonium; OG’, oogonium in formation; P, paraphysis; SM, sperm; SO, sorus; SP, sporophyll; and US, unilocular sporangium. Drawings were made based on photomicrographs taken during this study.

Percentage meiospore germination of (a) M. pyrifera and (b) U. pinnatifida after 6 days of culture in a factorial combination of two temperatures (12 and 16 °C), two pH (pHT 7.65 and 8.16) and two copper (No-Cu, and Cu-EC50 = 2.36 and 3.62 µM Cu for M. pyrifera and U. pinnatifida, respectively) treatments. Bars represent mean ± SD (n = 4). Significant subgroups are grouped by the lowercase groups as a > b > c (Tukey, P < 0.05). Note that the y-axis has a break from 10 to 70% in both graphs.

Germling growth rate

The growth rate of sexually ambiguous germlings (Fig. 1) was calculated for both species (1–12 d for germlings under No-Cu and 1–9 d for those under Cu-EC50; Supplementary Fig. S1). When taken as individual factors, OW and OA significantly (P < 0.005) increased the growth rate of M. pyrifera germlings (7–20% increase) (Fig. 3a). In contrast, the growth of U. pinnatifida germlings was not affected by OW or OA (P > 0.05) (Fig. 3b). An additional significant (P < 0.001) effect of copper, causing a reduction in germling growth rate of M. pyrifera (by 46–63%) and U. pinnatifida (by 56–68%) was observed in all treatment combinations (Fig. 3).

Growth rate of germlings of (a) M. pyrifera and (b) U. pinnatifida after 12 days of cultivation in a factorial combination of two temperatures (12 and 16 °C), two pH (pHT 7.65 and 8.16) and two copper (No-Cu, and Cu-EC50 = 2.36 and 3.62 µM Cu for M. pyrifera and U. pinnatifida, respectively) treatments. Bars represent mean ± SD (n = 4). Significant subgroups are grouped by the lowercase groups as a > b > c > d (Tukey, P < 0.05).

Gametophyte size

Sexual differentiation of gametophytes (Fig. 1) occurred at the 15th day of culture for both species under No-Cu conditions. Gametophyte development and sexual differentiation were significantly (P < 0.001) inhibited by copper exposure (Fig. 4). In the No-Cu treatment, gametophytes of M. pyrifera grew significantly bigger (18% increase for males and 46% increase for females; P < 0.05, Tukey test) under OA at 16 °C, and males were significantly (P < 0.001) bigger (29–54%) than females under all pH and temperature combinations (Fig. 4a). In contrast, only the size of female gametophytes of U. pinnatifida was significantly (P < 0.05, Tukey test) reduced (24%) by OA at 12 °C compared to those at pHT 8.16 at 12 °C (Fig. 4b).

Size of male and female gametophytes of (a) M. pyrifera and (b) U. pinnatifida at the 15th day of cultivation in a factorial combination of two temperatures (12 and 16 °C) and two pH (pHT 7.65 and 8.16) treatments under control (no-copper addition) treatment. No data is available for the Cu-EC50 treatment as sexual differentiation was inhibited by copper exposure. Bars represent mean ± SD (n = 4). Significant subgroups are grouped by the lowercase groups as a > b > c > d (Tukey, P < 0.05). Note that the y-axis has a break from 100 to 500 µm2.

Gametophyte sex ratio

After 15 days, the sex ratio of sexually differentiated gametophytes under No-Cu treatment of both species varied between 0.47 and 0.53 but was not significantly affected by single factors nor their interactions (Supplementary Fig. S2).

Germling growth rate during the recovery period

The growth rate of sexually ambiguous germlings (Fig. 1) during the recovery period (after stopping copper addition to the media of the Cu-EC50 treatments on day 9) was calculated from day 12 to 18 for both species. In M. pyrifera, recovery of germling growth rate was significantly (P = 0.026) 7 and 25% greater in OA conditions compared to the current pHT treatment at 12 or 16 °C, respectively (Fig. 5a). In contrast, OW, OA and their interactions did not significantly affect germling growth rate of U. pinnatifida during recovery (Fig. 5b). Moreover, recovering germlings of both kelps did not differentiate into male or female gametophytes by the end of the experimental period (day 18). When comparing the growth rate during the recovery period (Fig. 5) with that during the Cu-EC50 exposure (Fig. 3), the germling growth rate of M. pyrifera significantly (P < 0.001) increased. That increase in growth rate of M. pyrifera was 29–33% greater under pHT 7.65 and 12 °C compared to pH 8.16 and 16 °C (P < 0.05, Tukey test). There were no statistical differences between growth rate during copper exposure and recovery for U. pinnatifida germlings under all pH and temperature combinations.

Growth rate for germlings of (a) M. pyrifera and (b) U. pinnatifida during recovery from copper Cu-EC50 exposure at corresponding temperatures (12 and 16 °C) and pHT (7.65 and 8.16). Growth rate was calculated from day 12 to 18. Bars represent mean ± SD (n = 4). Significant subgroups are grouped by the lowercase groups as a > b (Tukey, P < 0.05).

Total dissolved copper (CuT) concentrations

At the nominal copper concentrations corresponding to the Cu-EC50 for M. pyrifera (2.36 µM Cu) and U. pinnatifida (3.62 µM Cu), CuT concentrations measured in the fresh media were 2.51 and to 3.84 µM CuT, respectively (Table 1). During the first 9 days of culture, when the media corresponding to the different treatments was renewed every third day, the dissolved concentration of CuT was reduced by 64–71% for M. pyrifera and by 66–72% for U. pinnatifida, under all temperature and pH treatment combinations. Although copper was not added on the 12th and 15th day of culture, CuT was still detectable in the culture media, but at much lower concentrations compared to the period when copper-treatment media was renewed every 3 days (Table 1).

Labile copper (Cu’) concentrations

During the first 9 days of culture, Cu’ concentrations varied between 0.157 and 0.268 µM in the culture media of M. pyrifera and between 0.252 and 0.456 µM in the culture media of U. pinnatifida, under all temperature and pH treatment combinations. Although copper was not added on the 12th and 15th day of culture, Cu’ was detectable but at much lower concentrations compared to the copper-added period (Table 1).

Copper-binding ligand (L) concentration

Due to the high CuT in the media during days 0–9, L concentrations present in the cultures were undetectable. After the removal of Cu from the media (day 9), L was detected on day 12 and 15 (Table 1). At 12 °C and under both pH treatments, L release was higher (by >40%) on day 12 than day 15 in the culture media of both M. pyrifera and U. pinnatifida. At 16 °C, L release in the culture media of both kelps under pH 8.16 was higher (by >30%) on day 12 than day 15 while under pH 7.65 L production was lower (>50%) on day 12 than day 15 (Table 1).

Discussion

Our results reveal that local anthropogenic drivers such as copper pollution have a greater impact on kelp meiospore survival and ontogenic development than global climate drivers such as OW and OA. While the independent effects of OW and OA on different early life history stage processes (e.g., meiospore germination and gametophyte growth) are mostly insignificant, the effect of copper is negative and magnified through the different developmental stages. For example, in our experiments, copper exposure (Cu-EC50) had only a moderate negative effect (5–18% reduction) on meiospore germination for all OW treatment and the ambient temperature/OA treatment and no effect for the ambient pH/temperature treatment. However, the subsequent growth of germlings was reduced by 43–68%, and sexual differentiation was inhibited regardless of seawater temperature and pH. The different sensitivities of early life history stage processes, not only to copper exposure, but also to other environmental drivers, are related to the fact that meiospore germination is an autogenous process supported by cellular lipid reserves38,39,40 while gametophyte growth and subsequent life-history processes are dependent on the photosynthesis and factors affecting this process40,41.

Despite the initial germination process being autogenous, copper exposure can interfere with germ tube initiation in brown seaweeds. In the Fucales, Ca2+ movement across the cell membrane of zygotes generates an electrical gradient that initiates the movement of negatively charged vesicles into the basal pole, leading to adhesion and rhizoid formation and germ tube formation42,43. An excess of copper may alter Ca2+ membrane permeability inhibiting cellular polarization and delay germination in brown macroalgae42,43. For example, germination and rhizoid elongation in the brown macroalgae Fucus serratus (Order Fucales) was inhibited by copper at 0–2.11 µM Cu44 while Cu-EC50 for spore germination in M. pyrifera and U. pinnatifida are 2.36 and 3.62 µM CuT, respectively. Following the transport of copper into the cytosol, copper disrupts enzyme-active sites and cell division45,46. In various organelles, copper interferes with mitochondrial electron transport, respiration, ATP production, and photosynthesis in the chloroplast47. The multiple effects of copper in subcellular organelles is likely responsible for the more pronounced effects on germling and gametophyte growth compared to meiospore germination in our experiment.

In general, the production of L seems to be the first line of defence by macroalgae against copper toxicity conferring some degree of tolerance by neutralizing the negative effect of copper21,24. In our study, when copper was removed, M. pyrifera germling growth rate was significantly enhanced under OA regardless of temperature whereas U. pinnatifida germling growth did not significantly increase under OA, OW or ambient conditions, indicating a more serious disruption of the development of M. pyrifera germlings under copper stress. In addition, since L cannot to be detected when Cu’ is in excess of CuL27, after removing copper from the medium at day 9 onwards, L was detected in cultures of both species. L in the No-Cu treatments was significantly lower than that in Cu-EC50 treatment, especially for U. pinnatifida, suggesting that L release is an active response to Cu stress that enabled the cells to resume growth during the recovery phase. The production of L in response to copper exposure has been reported in adult macroalgae21,24, but, to our knowledge, this is the first study showing L production by microscopic early life history stages of the Order Laminariales.

L were not detectable during copper exposure (day 1–9) using our method, but the observed difference between CuT and Cu’ under No-Cu and Cu-EC50 treatment indicates the presence of L, and we suggest that L was already actively produced during that period. The apparent L production may have helped to protect and detoxify kelp cells, thereby promoting germling growth, albeit at very low rates.

Considering that M. pyrifera and U. pinnatifida were exposed to different germination Cu-EC50 values (2.36 µM for M. pyrifera and 3.62 µM for U. pinnatifida5), it is noteworthy that growth rate under these Cu-EC50 treatments (Fig. 3) was comparable between the two species. However, during recovery (day 12–18), M. pyrifera germling growth rates were significantly enhanced under OA, regardless of temperature while the growth of U. pinnatifida germling remained at the same rate at that observed during copper exposure, regardless of pH and temperature treatments. As the Cu-EC50 was 35% greater for U. pinnatifida (3.84 µM CuT) compared to M. pyrifera (2.51 µM CuT), it is likely that the higher levels of remaining Cu in the U. pinnatifida cultures adsorbed into the container and/or the cell wall and negatively affected growth rate recovery germlings. In contrast, there was less Cu remaining in the M. pyrifera cultures and the higher pCO2 (Table 2) enhanced the growth rate of germlings.

The species-specific response to copper toxicity observed for M. pyrifera and U. pinnatifida may also be attributed to bacteria that inhabit macroalgal surface. The surface of macroalgae is a nutrient-rich habitat that is optimal for colonization by bacteria48. Bacteria associated with macroalgae can also exude L for binding and transport metals required for several physiological processes of bacteria such as nitrogen fixation49. Thus, L released by bacteria can play an additional protective role for macroalgae against metal pollution24,49. For example, research on M. pyrifera from California indicated that populations from highly copper-polluted coasts have epibiotic bacteria with greater copper tolerance compared with those from less copper-impacted coasts50. Therefore, although bacteria were not observed by light microscopy during our experiment, it is possible that bacteria increased the metal tolerance of different life stages of kelps under copper exposure, but this needs further investigation.

The effects of copper on M. pyrifera and U. pinnatifida became apparent at the germling and gametogenesis stages of both species, with the growth rate of germlings being significantly lower and gametophyte development (growth and sexual differentiation) arrested in all temperature and pH treatments when copper was added. Trace metals, including copper, are known to promote oxidative damage by increasing the cellular concentration of reactive oxygen species (ROS) such as the superoxide anion (O2−), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and the hydroxyl radical (OH−), and by disrupting the photosynthetic electron chain and reducing the cellular antioxidant capacity in macroalgae51,52. At high concentrations, ROS are toxic to all organisms, oxidizing proteins, lipids and nucleic acids that often lead to structural aberrations, mutagenesis, and cell death51. Consequently, the presence of ROS likely resulted in the observed low germination and growth rates under copper exposure. In addition, this response might be related to copper inhibiting the utilization (but not the production) of vesicle-stored reserves, e.g., alginic acid38,40,53, as the growth of germlings depends on the formation of the new cell wall that contains alginic acid54,55. This suggests that copper was preventing cell expansion and growth of M. pyrifera and U. pinnatifida germlings during the Cu-EC50 exposure in this study.

The initial CuT concentrations were reduced during the 9-day Cu-EC50 exposure likely due to adsorption into exopolysaccharides. This suggestion is supported by the observations that macro- and microalgae and bacteria, over-produce cell wall polysaccharides in response to trace metal pollution to avoid absorption of metals into the cell56,57. The negatively-charged active groups (i.e., hydroxyl, sulphate, and carboxyl) of polysaccharides are strong ion-exchangers, and so have a high capacity to bind (i.e., bioadsorb) trace metal ions such as Cu2+ 56. The extracellular polysaccharide, alginate (i.e., insoluble salt of alginic acid), occurs naturally in brown macroalgae (Ochrophyta, Phaeophyceae) as a major structural component of the matrix of cell wall56. It is possible that developing meiospores (in both No-Cu and Cu-EC50 treatments) produced enough alginate to block cellular entry of copper to the cytosol, thereby limiting subcellular toxic effects of copper. This protective mechanism might have been operating during the development of M. pyrifera and U. pinnatifida meiospores in our experiment, but to assess this, further studies on the production of cell wall polysaccharides by kelp meiospores during copper exposure are required.

Millions of meiospores (e.g., >5 × 103 cell mL−1 cm of sorus area−2) are produced by one fertile sporophyte29 so the individual and interactive effects of OW and OA on meiospore germination would be small (15%) and cause little concern. However, upon release, the meiospores are exposed to different abiotic drivers that can already significantly reduce their number before any effect of OW and OA (Fig. 6). These factors include: (1) large-scale hydrodynamics, such as currents affecting the density and the physical transport of the larval pool; (2) micro-hydrodynamics, such as small-scale currents and spatial variability that may determine settlement; and (3) substrate availability and quality, substrate preference and spore settlement behaviour, e.g. phototaxis, chemotaxis58. Furthermore, grazing on gametophytes and juvenile sporophytes can further contribute to the decimation and the collapse of the local kelp population59,60. The surviving individuals (gametophytes) give rise to the next life history stage (sporophytes) which may be able to withstand exposure to OW and OA due to better acclimation and subsequent adaptation61. However, the effect of copper, a relevant local stressor, is more concerning as sexual differentiation and subsequently, sexual reproduction will be arrested further compromising the development of the next generation of sporophytes.

Schematic representation of the bottleneck effect produced by drivers that may influence meiospore settlement and subsequent development into an adult sporophyte population of kelps. Results of the current experiment indicate that early life stages of kelps are susceptible to the interaction between OW, OA and Cu but other drivers may affect the same and different developmental stages. For example, swimming meiospores are affected by large-scale hydrodynamics (e.g., currents) impacting their density and physical transport to the substratum. Micro-hydrodynamics (e.g., small-scale currents) may determine meiospore settlement and subsequent development. Simultaneously, early life history stages of kelps are constantly stressed by the interactions of abiotic (e.g., OW, OA, Cu) and biotic (e.g., grazing) drivers. All these interactions control the dynamic and structure of the adult populations. Adapted from Pineda66. Diagram is not drawn to scale.

Methods

Preparation of trace metal clean, laboratory–ware

All laboratory–ware used for stock solution preparation, seawater sampling and meiospore cultures were acid-cleaned and ultrapure water-rinsed to reduce contamination by trace metals contamination36, microalgae and bacteria24. Manipulation (e.g., culture media renewal and sampling) during the experiment was performed inside a laminar flow cabinet to minimize contamination36.

Copper stock solution and nominal concentrations

The copper stock solution was prepared by dissolving CuCl2 in ultrapure water (2 g L−1 CuCl2, i.e., 14.9 mM Cu) in a 100-mL polycarbonate bottle (NalgeneTM, Nalge Nunc International Corporation, NY, U.S.A.) and stabilized by adding 2 M HCl until reaching pH 2.436. This stock solution was prepared at the beginning of the experiment. The nominal copper concentrations used in this experiment were the theoretical Cu concentration received when diluting the stock solution for each treatment. We aimed for the species-specific CuT concentrations that inhibits 50% of germinations (Cu-EC50 treatment) of 2.36 µM for M. pyrifera and 3.62 µM for U. pinnatifida5. No-Cu treatment corresponded to the media without any Cu stock addition.

Total dissolved copper (CuT) analysis

CuT in the 0.2 µm-filtered solution was measured in the fresh culture media before exposure to the meiospores and at day 0–15. CuT in the culture media was determined from two replicates of each copper treatment and the analytical blanks. An amount of 0.15 mL of culture medium was diluted in 4.25 mL of ultrapure water and acidified with 0.10 mL of HNO3 (acidified sample, 4.5 mL 2% HNO3) and stored until analysis. Total copper concentrations were quantified by inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS)5.

Labile copper (Cu’) and copper-binding ligand (L) analyses

Cu’ and L in solution were measured from the meiospore culture media on day 0–15. Due to a large number of samples and time requirements for each analysis, Cu’ and natural L concentrations were determined from one sample of each copper treatment by cathodic stripping voltammetry (CSV) of freshly thawed samples at the ambient pH. Good reproducibility was demonstrated for one sample (i.e., U. pinnatifida, 12 °C and pHT 7.65) on day 6. Due to the limited seawater volumes available, the large number of samples and the fact that most of the samples contained high amounts of copper (i.e., in excess of natural L), a kinetic approach as described for Fe with 1-nitroso-2-naphthol in Witter and Luther III27 was used here for Cu with salicylaldoxime (SA) as the competing L62. Briefly, to determine Cu’, [CuL] and therefore [L], SA was added to a final concentration of 100 µmol L−1. The current was monitored immediately after the addition of SA and until the system reached equilibrium, which was reached at a maximum of 2 h. The current measured right after the addition of SA represents the Cu’ and the difference after 2 h additionally include [CuL]. This assumes that due to the large excess of SA over L, any Cu’ formed during the dissociation of CuL will react faster with SA than with L, and the product CuSAx will not revert to Cu’ during the timescale of the analysis27. At the end of the equilibration time a two-fold standard addition was performed to derive the Cu’ concentration. The standard addition curves were in all cases linear, indicating that no free L was present at that time. For samples at Cu-EC50 concentrations, no CuL could be detected, i.e. there was no significant difference between the current measured right after the addition of SA and after equilibration of 2 h. However, we could still derive Cu’ from our analysis. For No-Cu treatments and samples taken during the recovery period, i.e. 9–15 days, the current increased during the equilibration time and [CuL] could be approximated. The errors associated with the analysis, however, were too large to derive meaningful stability constants from these measurements and we therefore report only the L concentrations.

Sampling location and sporophyll collection

M. pyrifera and U. pinnatifida can be found cohabiting in the shallow subtidal zone in Hamilton Bay (45°47′51″S; 170°38′39″E), as well as in other bays within the Otago Harbour, New Zealand63. The surface seawater temperature in the Otago Harbour varies between 6 and 18 °C annually, with seasonal ranges of 15 to 18 °C in summer, 10 to 16 °C in autumn, 6 to 9 °C in winter, and 10 to 15 °C in spring64,65. Sporophylls with fertile tissue (i.e., sori) were collected from ten adult sporophytes of M. pyrifera and U. pinnatifida during low tide from the upper sub-littoral zone of Hamilton Bay in November 2014 (Southern Hemisphere’ spring). In the laboratory, collected sporophylls were lightly brushed and cleaned of visible epibiota under filtered (0.2 µm, Whatman™ Polycap™ TC filter capsule, GE Healthcare Life Sciences, UK) seawater, blotted dry, wrapped in tissue paper and kept overnight at 4 °C to induce dehydration before meiospore release.

Seawater pH measurements

The seawater pH during the experiment was measured on the total scale (pHT) at 12 and 16 °C using a pH electrode (Orion ROSS Sure-Flow semi-micro, ORI8175BNWPW) connected to a pH meter (Thermo Scientific Orion 720 A pH/ION Meter). The electrode slope was determined using temperature equilibrated pH 7 and pH 9 buffers (colour coded, NIST traceable). pH was measured on the total scale using TRIS and 2-aminopyridine buffers in synthetic seawater to calibrate the electrode66. Seawater samples representing the two pHT treatments were collected and fixed with mercuric chloride for determining seawater carbonate chemistry. Total alkalinity (AT) was measured using the closed-cell titration method and dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC) was measured directly by acidifying the sample66. The seawater carbonate chemistry of each pH treatment at both temperatures was calculated using the measured AT, DIC, pH, salinity, and temperature (Table 2) with the SWCO2 software67.

Seawater pH treatments

The seawater used in the experiment was collected at the same time as the sporophylls and had a salinity of 36‰. The seawater was filtered (0.2 µm) to reduce microalgal and bacterial contamination and kept overnight in previously sterilized 2 L-polycarbonate bottles at the respective temperature treatment before use. After filtration, nutrients (10 µM NaNO3 and 1 µM NaH2PO4) were added to the seawater to avoid nutrient limitation. The present pH treatment corresponded to the non-manipulated seawater (pHT 8.16, defined as ambient treatment). To obtain the lowest seawater pH treatment (pHT 7.65, defined as OA treatment), equal volumes of 0.5 M HCl and 0.5 M NaHCO3 were added to the seawater68,69 until pHT reached 7.65 at 16 °C. Seawater with the corresponding pHT was freshly prepared every three days to renew the culture medium.

Effects of seawater temperature, pH, and copper on meiospore development

Meiospore release and cultivation were performed as described in Leal et al.32. Briefly, from each species, discs (2 cm2) of mature sorus were cut from the sporophylls using a cork borer. Pools of excised sori (total of ca. 50 g of 2 cm2 discs each) of both kelp species were separately immersed in seawater of the different pHT and temperature treatments for 15 min. After release, meiospores were dispensed (final density of 25,000 cell·mL−1) into culture flasks (Corning® 75 cm2, polystyrene cell culture flask with phenolic-style cap) containing seawater with the corresponding pHT and temperature but without copper addition. To avoid meiospore mortality during swimming and settlement that could change the initial density, meiospores were allowed to settle for 3 h before exposure to the respective nutrient-amended seawater and copper concentration treatments. Exposure to copper lasted 9 days, which is the time observed to inhibit gametogenesis in both kelp species5. Meiospore cultures of both species under the respective pHT and copper treatments were prepared in two sets and each one was exposed to the respective temperature treatment (12 and 16 °C) in two identical temperature-controlled chambers (Contherm Plant Growth Chamber, Contherm Scientific Co. Ltd., New Zealand). PAR (metal halide lamps Philips HPI- T 400 W quartz), with a photoperiod of 12 h light: 12 h dark, was measured with a spherical quantum sensor (LI-193, LI-COR, Lincoln, Nebraska) connected to a light meter (LI-250A, LI-COR, Lincoln, Nebraska) and adjusted to 55 ± 2 and 54 ± 1 µmol photons·m−2 s−1 in the 12 °C- and 16 °C-culture room, respectively. Thereafter, Cu-treated samples were allowed to recover using the culture medium with nutrients but without copper addition, under the respective scenario. Analytical blanks (i.e., seawater with each copper concentration under the respective pH and temperature conditions but without biological material) corresponding to each copper treatment were also prepared. The media of the meiospore cultures with the appropriate pHT, copper, and nutrients (to avoid nutrient depletion), were renewed every 3 days. CuT concentrations in the treatments and blanks were measured as described above.

Meiospore development

M. pyrifera and U. pinnatifida meiospore germination (%), germling growth rate (%·day−1), gametophyte size (µm2) and sex ratio, during the experiment, were obtained from photograph (5.1 M CMOS camera, UCMOS0510KPA) taken every three days from at least five haphazardly chosen visual fields, using an inverted microscope (200×, Olympus CK2; Olympus Optical Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). Photographs were analysed using the ToupView 3.5 digital camera software (ToupTek Photonics, Zhejiang, China). Meiospores with visible germ tubes were considered germinated and the germination percentage was calculated from 350 individuals per replicate after 6 d of culture. The size of sexually ambiguous growing meiospores (germlings) and sexually-differentiated male and female gametophytes was obtained from an average of 30 individuals per replicate after 12 and 15 d of culture, respectively. Germling growth rate under No-Cu and Cu-EC50 treatments were separately calculated during exposure and recovery. For germlings under No-Cu treatment, growth rate was calculated from 0 to 12 d, before sexual differentiation was observed in both kelps. For germlings under Cu-EC50 treatment, growth rate was calculated during copper exposure (0–9 d) and during recovery period (12–18 d). Growth rate (%·day−1) was calculated as [(Wt/W0)1/t−1] × 100, where W0 is the initial size, Wt is the final size, and t is days of culture70. At day 15, when sexual ambiguity was resolved, male and female gametophytes were counted and the sex ratio, expressed as the frequency of males per progeny, was calculated as no. ♂/(no. ♂ + no. ♀)69.

Statistical analyses

We did not statistically compare the two species in the present work because M. pyrifera and U. pinnatifida showed species-specific responses to copper5, OA and/or OW32,33 in previous studies. Percentage germination and germling growth rate (%·day−1) were logit transformed71. All the data satisfied Normality (Kolgomorov-Smirnov test) and homogeneity of variances (Levene’s test). Three-way ANOVA (P < 0.05) was used to test the statistical significance of differences in meiospore germination, germling growth rate during copper exposure, gametophyte size, germling growth rate (copper exposure vs. recovery period) between temperature, pH, copper treatments, and sex. Two-way ANOVA (P < 0.05) was used to test the statistical significance of differences in gametophyte sex ratio and germling growth rate (during recovery) between temperature and pH. When significant interactive effects were observed in the ANOVAs (at α = 0.05), the significant main effects of the factors (i.e., temperature, pH, copper treatments and sex) were subordinated, and the interaction(s) becomes the focus of the analysis72. A post hoc Tukey test (P < 0.05) was applied when a significant effect (single, two- and/or three-way interactions) of independent variables was observed. The ANOVA analyses were run using the software SigmaPlot version 12.0 (Systat Software, Inc., San Jose, CA). ANOVA statistical results for M. pyrifera and U. pinnatifida are listed in Supplementary Tables S1 and S2, respectively.

References

IPCC. Climate change 2013: the physical science basis. Contribution of working group I to the fifth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change. (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, 2013).

Koch, M., Bowes, G., Ross, C. & Zhang, X. H. Climate change and ocean acidification effects on seagrasses and marine macroalgae. Glob. Chang. Biol. 19, 103–132 (2013).

Halpern, B. S. et al. A global map of human impact on marine ecosystems. Science (80-) 319, 948–952 (2008).

Gledhill, M., Nimmo, M., Stephen, J. H. & Brown, M. T. The toxicity of copper(II) species to marine algae, with particular reference to macroalgae. J. Phycol. 33, 2–11 (1997).

Leal, P. P., Hurd, C. L., Sander, S. G., Kortner, B. & Roleda, M. Y. Exposure to chronic and high dissolved copper concentrations impede meiospore development of the kelps Macrocystis pyrifera and Undaria pinnatifida (Ochrophyta). Phycologia 55, 12–20 (2016).

Millero, F. J., Woosley, R., DiTrolio, B. R. & Waters, J. Effects of the ocean acidification on the speciation of metals in seawater. Oceanography 22, 72–85 (2009).

Zeng, X., Chen, X. & Zhuang, J. The positive relationship between ocean acidification and pollution. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 91, 14–21 (2015).

Abualhaija, M. M., Whitby, H. & van den Berg, C. M. G. Competition between copper and iron for humic ligands in estuarine waters. Mar. Chem. 172, 46–56 (2015).

Worms, I., Simon, D. F., Hassler, C. S. & Wilkinson, K. J. Bioavailability of trace metals to aquatic microorganisms: importance of chemical, biological and physical processes on biouptake. Biochimie 88, 1721–31 (2006).

Richard, Y. et al. Temperature changes in the mid-and high-latitudes of the Southern Hemisphere. Int. J. Climatol. 33, 1948–1963 (2013).

Russell, B. D. & Connell, S. D. Origins and consequences of global and local stressors: incorporating climatic and non-climatic phenomena that buffer or accelerate ecological change. Mar. Biol. 159, 2633–2639 (2012).

Clayson, C. A. & Bogdanoff, A. S. The effect of diurnal sea surface temperature warming on climatological air–sea fluxes. J. Clim. 26, 2546–2556 (2013).

Large, W. G. & Caron, J. M. Diurnal cycling of sea surface temperature, salinity, and current in the CESM coupled climate model. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 120, 3711–3729 (2015).

Hofmann, G. E. et al. High-frequency dynamics of ocean pH: a multi-ecosystem comparison. Plos One 6, e28983 (2011).

Cornwall, C. E. et al. Diurnal fluctuations in seawater pH influence the response of a calcifying macroalga to ocean acidification. Proc. R. Soc. B 280, 20132201 (2013).

Lewis, A. G. Copper in water and aquatic environments (1995).

Nor, Y. M. Ecotoxicity of copper to aquatic biota: a review. Environ. Res. 43, 274–282 (1987).

Correa, J. A. et al. Copper, copper mine tailings and their effect on marine algae in Northern Chile. J. Appl. Phycol. 11, 57–67 (1999).

Raven, J. A. Inorganic carbon concentrating mechanisms in relation to the biology of algae. Photosynth. Res 77, 155–71 (2003).

Krämer, U. & Clemens, S. Functions and homeostasis of zinc, copper, and nickel in plants. In Molecular Bology of Metal Homeostasis and Detoxification from Microbes to Man (eds Tamás, M. J. & Martinoia, E.) 14, 214–272 (Springer-Verlag, 2006).

Murray, H., Meunier, G., van den Berg, C. M. G., Cave, R. R. & Stengel, D. B. Voltammetric characterisation of macroalgae-exuded organic ligands (L) in response to Cu and Zn: a source and stimuli for L. Environ. Chem. 11, 100–113 (2014).

Croot, P. L., Moffett, J. W. & Brand, L. E. Production of extracellular Cu complexing ligands by eukaryotic phytoplankton in response to Cu stress. Limnol. Oceanogr. 45, 619–627 (2000).

Sueur, S., van den Berg, C. M. G. & Riley, J. P. Measurement of the metal complexing ability of exudates of marine macroalgae. Limnol. Oceanogr. 27, 536–543 (1982).

Gledhill, M., Nimmo, M., Hill, S. J. & Brown, M. T. The release of copper-complexing ligands by the brown alga Fucus vesiculosus (Phaeophyceae) in response to increasing total copper levels. J. Phycol. 35, 501–509 (1999).

Vasconcelos, M. T. S. D. & Leal, M. F. C. Seasonal variability in the kinetics of Cu, Pb, Cd and Hg accumulation by macroalgae. Mar. Chem. 74, 65–85 (2001).

Bruland, K. W., Rue, E. L., Donat, J. R., Skrabal, S. A. & Moffett, J. W. Intercomparison of voltammetric techniques to determine the chemical speciation of dissolved copper in a coastal seawater sample. Anal. Chim. Acta 405, 99–113 (2000).

Witter, A. E. & Luther, G. W. III. Variation in Fe-organic complexation with depth in the Northwestern Atlantic Ocean as determined using a kinetic approach. Mar. Chem. 62, 241–258 (1998).

Witter, A. E., Hutchins, D. A., Butler, A. & Luther, G. W. III. Determination of conditional stability constants and kinetic constants for strong model Fe-binding ligands in seawater. Mar. Chem. 69, 1–17 (2000).

Leal, P. P., Hurd, C. L. & Roleda, M. Y. Meiospores produced in sori of non-sporophyllous laminae of Macrocystis pyrifera (Laminariales, Phaephyceae) may enhance reproductive output. J. Phycol. 50, 400–405 (2014).

Xie, Z. C., Nga, C. W., Qian, P. Y. & Qiu, J. W. Responses of polychaete Hydroides elegans life stages to copper stress. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 285, 89–96 (2005).

Nielsen, S. L., Nielsen, H. D. & Pedersen, M. F. Juvenile life stages of the brown alga Fucus serratus L. are more sensitive to combined stress from high copper concentration and temperature than adults. Mar. Biol. 161, 1895–1904 (2014).

Leal, P. P., Hurd, C. L., Fernández, P. A. & Roleda, M. Y. Ocean acidification and kelp development: reduced pH has no negative effects on meiospore germination and gametophyte development of Macrocystis pyrifera and Undaria pinnatifida. J. Phycol. 53, 557–566 (2017).

Leal, P. P., Hurd, C. L., Fernández, P. A. & Roleda, M. Y. Meiospore development of the kelps Macrocystis pyrifera and Undaria pinnatifida under ocean acidification and ocean warming: independent effects are more important than their interaction. Mar. Biol. 164, 7 (2017).

Campbell, A. L., Mangan, S., Ellis, R. P. & Lewis, C. Ocean acidification increases copper toxicity to the early life-history stages of the polychaete Arenicola marina in artificial seawater. Environ. Sci. Technol. 48, 9745–9753 (2014).

Roberts, D. A. et al. Ocean acidification increases the toxicity of contaminated sediments. Glob. Chang. Biol. 19, 340–351 (2013).

Leal, P. P., Hurd, C. L., Sander, S. G., Armstrong, E. A. & Roleda, M. Y. Copper ecotoxicology of marine algae: a methodological appraisal. Chem. Ecol. 32, 786–800 (2016).

Roleda, M. Y. et al. Effect of ocean acidification and pH fluctuations on the growth and development of coralline algal recruits, and an associated benthic algal assemblage. Plos One 10, e0140394 (2015).

Brzezinski, M. A., Reed, D. C. & Amsler, C. D. Neutral lipids as major storage products in zoospores of the giant kelp Macrocystis pyrifera (Phaeophyceae). J. Phycol. 29, 16–23 (1993).

Reed, D. C., Brzezinski, M. A., Coury, D. A., Graham, W. M. & Petty, R. L. Neutral lipids in macroalgal spores and their role in swimming. Mar. Biol. 133, 737–744 (1999).

Steinhoff, F. S., Graeve, M., Wiencke, C., Wulff, A. & Bischof, K. Lipid content and fatty acid consumption in zoospores/developing gametophytes of Saccharina latissima (Laminariales, Phaeophyceae) as potential precursors for secondary metabolites as phlorotannins. Polar Biol. 34, 1011–1018 (2011).

Amsler, C. D. & Neushul, M. Photosynthetic physiology and chemical composition of spores of the kelps Macrocystis pyrifera, Nereocystis luetkeana, Laminaria farlowii, and Pterygophora californica (Phaeophyceae). J. Phycol. 27, 26–34 (1991).

Anderson, B. S., Hunt, J. W., Turpen, S. L., Coulon, A. R. & Martin, M. Copper toxicity to microscopic stages of giant kelp Macrocystis pyrifera: interpopulation comparisons and temporal variability. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 68, 147–156 (1990).

Burridge, T. R., Portelli, T. & Ashton, P. Effect of sewage effluents on germination of three marine brown algal macrophytes. Mar. Freshw. Res. 47, 1009–1014 (1996).

Nielsen, H. D., Brown, M. T. & Brownlee, C. Cellular responses of developing Fucus serratus embryos exposed to elevated concentrations of Cu2+. Plant, Cell Environ. 26, 1737–1747 (2003).

Stauber, J. L. & Florence, T. M. Interactions of copper and manganese: a mechanism by which manganese alleviates copper toxicity to the marine diatom, Nitzschia closterium (Ehrenberg) W. Smith. Aquat. Toxicol. 7, 241–254 (1985).

Florence, T. M. & Stauber, J. L. Toxicity of copper complexes to the marine diatom Nitzschia closterium. Aquat. Toxicol. 8, 11–26 (1986).

Stauber, J. L. & Florence, T. M. Mechanism of toxicity of ionic copper and copper complexes to algae. Mar. Biol. 94, 511–519 (1987).

Armstrong, E. A., Yan, L., Boyd, K. G., Wright, P. C. & Burgess, J. G. The symbiotic role of marine microbes on living surfaces. Hydrobiologia 461, 37–40 (2001).

Wichard, T. Identification of metallophores and organic ligands in the chemosphere of the marine macroalga Ulva (Chlorophyta) and at land-sea interfaces. Front. Mar. Sci. 3, 131 (2016).

Busch, J., Nascimento, J. R., Magalhães, A. C. R., Dutilh, B. E. & Dinsdale, E. Copper tolerance and distribution of epibiotic bacteria associated with giant kelp Macrocystis pyrifera in southern California. Ecotoxicology 24, 1131–1140 (2015).

Pinto, E. et al. Heavy metal-induced oxidative stress in algae. J. Phycol. 39, 1008–1018 (2003).

Collén, J., Pinto, E., Pedersén, M. & Colepicolo, P. Induction of oxidative stress in the red macroalga Gracilaria tenuistipitata by pollutant metals. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 45, 337–342 (2003).

Reed, D. C., Amsler, C. D. & Ebeling, A. W. Dispersal in kelps: factors affecting spore swimming and competency. Ecology 73, 1577 (1992).

Bond, P. R. et al. Arrested development in Fucus spiralis (Phaeophyceae) germlings exposed to copper. Eur. J. Phycol. 34, 513–521 (1999).

Brawley, S. H., Wetherbee, R. & Quatrano, R. S. Fine-structural studies of the gametes and embryo of Fucus vesiculosus L.(Phaeophyta). II. The cytoplasm of the egg and young zygote. J. Cell Sci. 20, 255–271 (1976).

Davis, T. A., Volesky, B. & Mucci, A. A review of the biochemistry of heavy metal biosorption by brown algae. Water Res. 37, 4311–4330 (2003).

Hay, I. D., Rehman, Z. U., Moradali, M. F., Wang, Y. & Rehm, B. H. A. Microbial alginate production, modification and its applications. Microb. Biotechnol. 6, 637–650 (2013).

Pineda, J. Linking larval settlement to larval transport: assumptions, potentials, and pitfalls. Oceanogr. East. Pacific 1, 84–105 (2000).

Reed, D. et al. Extreme warming challenges sentinel status of kelp forests as indicators of climate change. Nat. Commun. 7, 13757 (2016).

Schiel, D. R. & Foster, M. S. The population biology of large brown seaweeds: ecological consequences of multiphase life histories in dynamic coastal environments. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 37, 343–372 (2006).

Harley, C. D. G. et al. Effects of climate change on global seaweed communities. J. Phycol. 48, 1064–1078 (2012).

Campos, M. L. A. M. & van den Berg, C. M. G. Determination of copper complexation in sea water by cathodic stripping voltammetry and ligand competition with salicylaldoxime. Anal. Chim. Acta 284, 481–496 (1994).

Russell, L. K., Hepburn, C. D., Hurd, C. L. & Stuart, M. D. The expanding range of Undaria pinnatifida in southern New Zealand: distribution, dispersal mechanisms and the invasion of wave-exposed environments. Biol. Invasions 10, 103–115 (2008).

Brown, M. T., Nyman, M. A., Keogh, J. A. & Chin, N. K. M. Seasonal growth of the giant kelp Macrocystis pyrifera in New Zealand. Mar. Biol. 129, 417–424 (1997).

Kregting, L. T., Hepburn, C. D., Hurd, C. L. & Pilditch, C. A. Seasonal patterns of growth and nutrient status of the macroalga Adamsiella chauvinii (Rhodophyta) in soft sediment environments. J. Exp. Mar. Bio. Ecol 360, 94–102 (2008).

Dickson, A. G., Sabine, C. L. & Christian, J. R. Guide to Best Practices for Ocean CO2 Measurements (2007).

Hunter, K. A. SWCO2. Available at, http://neon.otago.ac.nz/research/mfc/people/keith_hunter/software/swco2. (Accessed: 1st May 2015) (2007).

Riebesell, U., Fabry, V. J., Hansson, L. & Gattuso, J.-P. Guide to best practices for ocean acidification research. (Publications Office of the European Union, 2010).

Roleda, M. Y., Morris, J. N., McGraw, C. M. & Hurd, C. L. Ocean acidification and seaweed reproduction: increased CO2 ameliorates the negative effect of lowered pH on meiospore germination in the giant kelp Macrocystis pyrifera (Laminariales, Phaeophyceae). Glob. Chang. Biol. 18, 854–864 (2012).

Yong, Y. S., Yong, W. T. L. & Anton, A. Analysis of formulae for determination of seaweed growth rate. J. Appl. Phycol. 25, 1831–1834 (2013).

Warton, D. I. & Hui, F. K. The arcsine is asinine: the analysis of proportions in ecology. Ecology 92, 3–10 (2011).

Sokal, R. R. & Rohlf, F. J. Biometry: the principles and practice of statistics in biological research. (W. H. Freeman and Co., 2012).

Acknowledgements

We thank BECASCHILE-CONICYT, the Royal Society of New Zealand Mardsen grant (UOO0914) and the New Zealand MBIE programme C01X1005 for funding this study. The IAEA is grateful to the Government of the Principality of Monaco for the support provided to its Environment Laboratories.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.P.L., C.L.H., S.G.S., E.A. and M.Y.R. designed the study. P.P.L. and P.A.F. did field work and carried out the laboratory experiments. P.P.L. analysed the data. P.P.L. and M.Y.R. wrote the first draft of the manuscript and designed Figures 1 and 6, with subsequent contributions by other authors. S.G.S. and T.S. obtained the copper data in the laboratory.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Leal, P.P., Hurd, C.L., Sander, S.G. et al. Copper pollution exacerbates the effects of ocean acidification and warming on kelp microscopic early life stages. Sci Rep 8, 14763 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-32899-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-32899-w

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Metal content in Sardina pilchardus during the period 2014–2022 in the Canary Islands (Atlantic EC, Spain)

Environmental Science and Pollution Research (2024)

-

Joint effects of temperature and copper exposure on developmental and gene-expression responses of the marine copepod Tigriopus japonicus

Ecotoxicology (2023)

-

Harnessing MoO3/TiO2 Nanocomposites for Photocatalytic Reduction of [Cu(dien)(1-MeIm)Cl]Cl Complex: Paving the Way for Blue LED Application

Journal of Inorganic and Organometallic Polymers and Materials (2023)

-

Copper toxicity leads to accumulation of free amino acids and polyphenols in Phaeodactylum tricornutum diatoms

Environmental Science and Pollution Research (2023)

-

Climate change and species facilitation affect the recruitment of macroalgal marine forests

Scientific Reports (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.