Abstract

A minute fraction of atmospheric particles exert a disproportionate effect on the phase of mixed-phase clouds by acting as ice-nucleating particles (INPs). To understand the effects of these particles on weather and climate, both now and into the future, we must first develop a quantitative understanding of the major INP sources worldwide. Previous work has demonstrated that aerosols such as desert dusts are globally important INPs, but the role of biogenic INPs is unclear, with conflicting evidence for their importance. Here, we show that at a temperate site all INPs active above −18 °C at concentrations >0.1 L−1 are destroyed on heating, consistent with these INPs being of biological origin. Furthermore, we show that a global model of desert dust INPs dramatically underestimates the measured INP concentrations, but is consistent with the thermally-stable component. Notably, the heat sensitive INPs are active at temperatures where shallow cloud layers in Northern Europe are frequently observed to glaciate. Hence, we suggest that biogenic material is important for primary ice production in this region. The prevalence of heat sensitive, most likely biogenic, INPs in this region highlights that, as a community, we need to quantify the sources and transport of these particles as well as determine their atmospheric abundance across the globe and at cloud altitudes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The phase transition of water to ice in supercooled droplets can bring about precipitation and modulate the radiative properties of clouds1,2. Atmospheric aerosol can contain ice-nucleating particles (INPs)3, which permits primary ice nucleation at temperatures above about −33 °C, where the homogenous nucleation of supercooled water is so slow that water would otherwise persist in a supercooled state4. Common aerosol particles that are thought to be effective as INPs in the mixed-phase cloud regime include desert dusts5,6,7 and, in remote marine locations where dust concentrations are low, marine sea sprays8,9. While desert dust is thought to be a globally important INP type5,6, it has been found that shallow clouds over Morocco only glaciated below −18 °C, despite being collocated with dust10. In contrast, similar clouds in other terrestrial regions, such as N. Europe, typically glaciate at temperatures up to or even above −10 °C11. This difference is thought to be related to differences in INP populations rather than other variables such as cloud properties or meteorology11, but the INP type that drives this relatively high temperature nucleation in Northern Europe is unknown. While certain bioaerosols are known to be exceptional in their ice-nucleating abilities7,12 and have been posited as drivers of ice formation in clouds at low supercoolings13,14,15,16,17,18,19, there are conflicting conclusions regarding their global importance20,21. Although biogenic INPs have been examined since the 1960s (for extensive reviews of the general topic of ice nucleation, see Ashworth et al.22 Kanji et al.23 Hill et al.24 and Murray et al.12), a major source of uncertainty concerning the impacts of biogenic INPs is due to the lack of field studies that have determined their abundance relative to other ambient atmospheric INPs.

Biogenic components of INPs have previously been detected in precipitation samples collected at sites across the globe25,26,27,28. Estimates of atmospheric INP concentrations at cloud altitudes can be made based on the INP content of precipitation29 and heat tests suggest that some of these INP are biological25,27. In addition, measurements indicate that there is a major biogenic INP component in cloudwater at Puy De Dôme in France28. Also, Garcia et al.30 monitored the amounts of biogenic INPs released to the air from crops pre- and post- harvest in Colorado and Nebraska, and found using heat tests on sampled aerosol that a major proportion of emitted INPs were biogenic. In forested ecosystems, INPs have also been found to correlate well with the amount of fluorescent bioparticles and carbonaceous material in the aerosol31,32. Further suggestions for the importance of biological INPs in atmospheric ice nucleation have emerged from particle mass spectrometry of cloud ice crystal residues16,33. Notably, however, significant questions on the use of particle mass spectrometry to identify bioaerosols remain, in particular due to the potentially large misattribution rate based on the selected markers used34. Overall, despite there being evidence for biogenic INP in rain water and associated with specific events, such as harvests, there have been very few measurements of the relative importance of biological INPs versus other INP types in ambient aerosol samples around the world and none in the atmosphere of the UK.

Given the dearth of information on the contribution of biogenic INPs to the total burden, it is perhaps unsurprising that models simulating the impacts of biologically-derived INPs on clouds come to differing conclusions. In an aerosol-climate model, Hoose et al.20 simulated the global annual average INP concentrations using a subset of known biogenic ice-nucleating particles, including P. syringae bacteria. They found the proportion of nucleation due to bioaerosols was very small (≤0.6%). Similarly, Spracklen and Heald35 concluded that the fungal spores and bacteria only contribute a minor proportion of INPs, but do suggest that they may contribute to INP populations at warmer temperatures in some locations. However, these studies did not consider the possible roles of subcellular INPs, such as macromolecules, which are generated in large amounts by certain fungi and plants (e.g. pollen)36,37,38,39,40. These nanoscale entities could substantially increase the relative importance of biogenic particles as INPs37,41, especially if they become internally mixed with other aerosol particle types42,43. Conversely, using a cloud system resolving model, Phillips et al.21 concluded that cloud properties such as ice crystal number and precipitation are significantly influenced by bioaerosol particles when bioaerosol concentrations are elevated above average (but within previously observed levels). Despite these and other attempts to simulate the net contribution of biogenic INPs to cloud properties, the lack of field studies examining the biogenic INP burden in atmospheric aerosol makes it impossible to accurately predict their influence on clouds.

Results and Discussion

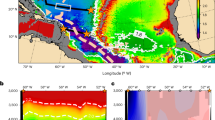

To quantify and characterise INPs in the atmosphere at a temperate site in Europe, a six week campaign was held at a rural location in the UK. INP concentrations at the site throughout the campaign are illustrated in Fig. 1a, where it can be seen that concentrations span more than two orders of magnitude at a particular temperature. For example, at an activation temperature of −18 °C, the INP concentration ranged from about 0.1 to 10 L−1. Such a wide variability has previously been seen at other ground based measurement sites. For instance, at a rural site in Italy, Belosi et al.44 report concentrations at −18 °C to fall within the range 0.07–1 INP L−1. Despite the wide variability in INP concentrations, Fig. 1a shows that there is a strong peak in frequency centred at about 2 INP L−1 at −22 °C. This distinct maximum in the INP concentration frequency plot is consistent with a single persistent INP type, whereas the concentrations at higher temperatures are consistent with a much more variable INP type.

Results from the six week INP measurement campaign at a rural site in the UK. Illustrated in (a) are INP concentrations observed throughout the campaign, colour-coded to the frequency of observation. Results of the heat tests are shown in (b). Also shown are cases when heating had only a small effect (c) and a large effect (d) on the activities above −20 °C.

Determining the nature of the INPs which make up the population in a typical atmospheric INP spectrum is challenging. This is in part because biogenic INPs are highly varied, being composed of whole cells, cell fragments or subcellular entities, such as proteins, which become internally mixed with other aerosol types, hence they are very difficult to identify directly. In this study we have used the commonly used heat treatment to assess the contribution of biogenic INPs to the overall INP population. This test is based on the fact that many known biological ice-nucleating materials nucleate ice because of the presence of specific ice-nucleating proteins. These proteins are disrupted and denatured on heating which inhibits their ice-nucleating ability whereas inorganic ice-nucleating materials tend to be insensitive to heat, hence heating a sample in water has become a standard and effective test for protein based biological ice-nucleating material9,45. Conversely, known inorganic INPs such as mineral dusts are not affected by heating to temperatures of about 100 °C46,47. Previously, studies have focused on examining the effects of heat treatment on either surface-collected samples such as soils45,46,48, leaf litter14,49 and sea water samples9,50, or on particles found in precipitation27,51 and aerosol collected during harvest periods30.

In the current study, greater than 100× reductions in INP concentrations were observed in the samples after heating to 95 °C for 1 hour, with reductions occurring mainly at T > −20 °C (Fig. 1b,c). In Fig. 1b, the heated samples are plotted alongside the original data. Most activity above −18 °C was removed on heating. At −20 °C, substantial reductions in activity (more than a factor of 2) were observed in 59% of heated samples. Conversely, for samples where nucleation was primarily observed to occur at temperatures below −20 °C, the effects of heating were less pronounced (Fig. 1c) than when nucleation began in the original samples above −20 °C (Fig. 1d). Following the loss of heat-labile INPs in the samples, the remaining activity was found to converge at the most frequently observed values prior to heating. This observation implies that there are at least two distinct populations of INPs in the samples with heat-labile INPs becoming more prominent at T > −20 °C, and a heat-resistant INP type at lower temperatures. It should be noted that heating does not eliminate all the biogenic INPs in a sample. A variety of biogenic INPs in surface soils are resistant to heat treatments below 100 °C45,48. Accordingly, the loss of INPs on heating can be viewed as a lower limit to the number of biogenic INPs in the sample. Overall, we find that the majority of INPs active at temperatures warmer than −18 °C at concentrations greater than 0.1 L−1 are destroyed on heating, and most likely of biological origin. Inspection of a filter with scanning electron microscopy revealed several biological particles which were most likely fungal spores (see SI Fig. 6). This shows that biological aerosol were present at this site, which is consistent with the presence of heat sensitive, most likely biological ice nucleating aerosol.

To investigate the sources of INPs, it was examined whether INP concentration was correlated with local meteorological variables including wind speed, ambient relative humidity and rainfall. The extent of correlations with local meteorological data is variable in literature data and changes from site to site44,52; although rainfall has been correlated with high INP concentrations in several locations26,31,53. For soil-derived particles, threshold friction velocities increase with factors such as soil wetness, which in turn is related to rainfall and surface relative humidity54. Conversely, increasing relative humidity has also been suggested to trigger the release of ice-nucleating aerosols from local biota55, while rain splashing on leaves and on soils56,57 has also been suggested to be a driver of biological INP emissions. In the current study, however, the coefficients of determination, R2, suggested little linear correlation between INP concentrations and a range of meteorological factors (Fig. 2). In addition, air mass back trajectories using the NOAA HYbrid Single Particle Lagrangian Integrated Trajectory (HYSPLIT) model58 did not indicate strong links between the origin of air masses and INP concentrations (Fig. 3). This is in contrast to what would be expected if there were a strong source of INPs within 2 days transport. For example, if the urban areas west of the sampling site were a strong source, we would anticipate a strong correlation with wind direction, or if there were a strong local source associated with rainfall then we would anticipate a correlation with rainfall. Instead, it seems that the INPs at this site are highly variable, but without an obvious local source. Given the landscape around the sampling site is representative of similarly heterogeneous landscape across North Western Europe and there is no dependence on air trajectory we suggest these results are representative of the wider region, although more measurements in more locations are needed to test this.

R2 correlation coefficients between log10[INP] and various meteorological parameters measured on-site. Illustrated are linear correlations to meteorological data collected from the collocated MET Office station, as well as total counts from the aerodynamic particle sizer (APS,) and scanning mobility particle sizer (SMPS). The duration of the sampling time was on average 3 hours (see SI Tables 1 and 2 for further details). The APS counts determined the number of particles with an aerodynamic diameter >0.5 µm, while the SMPS counted particles with mobility diameters in the range 14–710 nm. Poor linear correlation of INP concentrations with the indicated variables was observed.

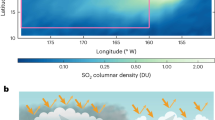

We now examine what the heat resistant INP type we observe may be. Desert dust is thought to be a globally important INP type16,59 with a lifetime in the accumulation mode on the order of days to weeks, hence it is transported in sufficient concentrations to contribute to the INP spectrum far from source regions6. Indeed, the fact that the back trajectories show that the sampled air did not recently pass over desert regions is entirely consistent with the presence of desert dust at our sampling location. To determine if the heat resistant INP we observed are consistent with transported desert dust, we compared our results with those predicated by the Global Model of Aerosol Processes (GLOMAP)6. INP concentrations simulated in GLOMAP from desert dust (K-feldspar) and marine sea spray emissions, i.e. neglecting other INP species such as terrestrial biogenics, were within one order of magnitude of 57% of the INP observations from around the globe5,6. As can be seen in Fig. 4a, it is expected that marine biogenics, whose nucleating activities are those parameterised by Wilson et al.9, are predicted to be of minor importance at this location. In Fig. 4a, we also show the concentration of INPs predicted from transported desert dusts, assuming the K-feldspar component is responsible for nucleation. K-feldspars have been demonstrated to show a far larger ice-nucleating activity than other minerals such as quartz, kaolinite or calcite5. Being the most ice-active mineral in desert dust found to date, and given its natural abundance, K-feldspar has been suggested to be of first order importance in determining the ice-nucleating activity of lofted desert dusts. Accordingly, the nucleating activities used here are taken from Atkinson et al. (A13)5 in conjunction with the modelled global K-feldspar distribution in order to estimate the INP concentration associated with desert dust. The initial fraction of desert dust which is feldspar is derived from soil composition maps from Claquin et al.60 Of this feldspar, 35% is assumed to be K-feldspar. Further details can be found in Vergara-Temprado et al.6. Two limiting assumptions are made, one where K-feldspar is externally mixed and one where it is internally mixed throughout the dust particle population. In reality, dust particles will be somewhere between these two mixing assumptions. In Fig. 4b, the desert dust activity was defined by the parameterisation of Niemand et al.61 (N12), which is based on surface samples from areas including the Nile delta, the Sahara and Israel.

Comparison of measured INP concentrations to those predicted using GLOMAP as detailed by Vergara-Temprado et al.6 (a), which uses parameterisations for ice nucleation activities based on K-feldspar and marine biogenic INPs, and separately, using the N1261 parameterisation for ice nucleation from desert dust (b). Terrestrial biogenic INPs are not parameterised in the model, which we suggest accounts for the under-predictions of the simulation at warmer temperatures. The width of the model predictions are based on the 20th and 80th percentiles of the daily averaged model outputs. The colours of the untreated data represent the frequency of observation, as in Fig. 1a.

Given the uncertainties in the accuracy of the model, due to uncertainties in the transport of dust and parameterisations of mineralogy and ice nucleating activities6, the agreement between the model-predicted INP concentrations and the heat resistant INPs is reasonable. Both the A13 and N12 parameterisations were found to yield reasonable agreement to observed heat-resistant INP concentrations. For the A13 parameterisation, the internal mixing assumption gives better agreement than the external mixing assumption. Overall, the thermally resistant component of INPs at this site is consistent with transported desert dust, defined by either N12 or A13, possibly together with heat resistant biological material. The presence of mineral dust within the aerosol at this site was confirmed through conducting energy dispersive x-ray analysis on a sample collected on the 17th Oct (see SI Fig. 5). We record the presence of particle compositions consistent with aluminosilicates and silicates dominantly in the coarse mode, amongst other aerosol types. Whether this dust is derived from desert regions or is from local sources is unclear, but the presence of mineral dust is consistent with the thermally stable INPs we detect in our experiments and the results of our two-component global INP model.

It is also evident from Fig. 4 that the model dramatically under-predicts the total (non-heat treated INP population) on many days. We have to be cautious when comparing a global model result with large grid boxes (2.8° × 2.8°) to a measurement at a single location since local emissions may strongly influence the measurements, but may make a minor contribution to concentrations on a model grid box scale. However, the comparison is valid if the site is representative of the grid box. Given we observe no evidence for strong specific local emissions, we have argued above that our measurements are broadly representative of the region. Testing this assumption will require far more measurements over a longer temporal and larger spatial scale than the present measurements. Nevertheless, the comparisons indicate that the model is missing a heat sensitive, most likely biogenic, source of INP. This is consistent with other work. For example, comparison of the GLOMAP INP model with measurements from around the world, revealed that in many mid-latitude terrestrial locations the INP concentrations were higher than the model predicted at temperatures warmer than −15 °C6, similar to this study. Also, shallow clouds were observed to glaciate at temperatures up to or even above −10 °C in N. Europe11, which is hard to explain with desert dust only and may be consistent with an additional source of INP. Overall, we suggest that there is an important missing source of INPs in the model and based on the heat tests we suggest that this missing source is most likely biogenic.

Conclusions

This work demonstrates that a major fraction of INPs found at a temperate rural site in Europe were sensitive to heat and therefore likely biogenic in origin, with this fraction becoming more important at warmer temperatures. Given that INPs active at several temperature intervals were found to be poorly correlated with local meteorology and back trajectories, the source of the heat-labile INPs remains unclear. Given that the landscape around the sampling site is similarly heterogeneous to much of the UK and Western Europe, it is argued that the results are of regional relevance. When a global model with no intrinsically defined terrestrial biogenic INP sources was used to examine if we could explain observed INPs above −20 °C, it under-predicts observations. This loss in the predictive capacity of the model coincides with temperatures where INPs were observed to be thermally-labile, suggesting an additional model source of heat labile, most likely biogenic, INPs is needed to account for the observations. This raises the possibility that the INP population in the atmosphere in this region is controlled by biogenic emissions from the terrestrial environment, which may be natural or linked to human activity. Accordingly, there is a possibility that INP populations, and their impact on clouds and climate, may be influenced by changes in land-use. Hence, work should continue to define the sources of INP in the mid-latitudes, determine their variability across a range of temporal scales and characterise their properties and transport.

Methods

Sample collection and analysis

Field experiments were conducted at the University of Leeds Research Farm (54 m above sea level; N53°52′7.086′′ W1°19′8.489′′) from 19/09/16 to 02/11/2016, during which time a mobile laboratory (the “IcePod”) equipped with a PM10 inlet (model URG-2000-30DBN-A, URG) and with an aerosol subsampling system was stationed at the site. Ambient particles were sampled onto 0.40 µm Nucleopore track-etched membrane polycarbonate filters at a flow rate of 5 L min−1. Note that these filters collect particles across the full aerosol size range, including at sizes below the size of the pore, with high efficiency62,63. Handling blanks, where the sampling system was set up and a HEPA filter placed on the inlet, were conducted to verify that in the absence of ambient particles contamination was not an issue (see SI). The average sampling time was approximately 3 hours, and the average volume of air sampled was 890 litres (see supplementary information). Further information can be found in Supplementary Information (SI) Tables 1 and 2. Aerosol number and size distributions were determined using both a Scanning Mobility Particle Sizer (SMPS) spectrometer (Model 3936, TSI), and an Aerodynamic Particle Sizer (APS) spectrometer (Model 3321, TSI). For comparison, electrical mobility diameters from the SMPS and aerodynamic diameters from the APS were converted to volume equivalent diameters as per Möhler et al.64. A compilation of all the particle size distributions is shown in SI Fig. 2, where the contributions from both the fine and coarse modes to the aerosol concentrations can be seen. Local wind and temperature characteristics, along with rainfall totals and relative humidity, were provided by the UK MET office from a collocated monitoring station.

Sampled INPs were extracted from filters by placing the filters into a centrifuge tube containing 5 mL Milli-Q® purified water, which was subsequently placed in a rotary mixer at 30 rpm. Detection of INPs was carried out using the Leeds microliter nucleation by immersed particles instrument (μL-NIPI)65. Nucleation was taken as the first visible occurrence of ice formation within the droplets, which was recorded using a high definition webcam. The cumulative number of INPs per mL of washing water (K(T)), was calculated using the singular approximation for ice nucleation as per Vali 197166:

where F(T) is the cumulative fraction of droplets frozen, and Vd is the droplet volume (0.001 mL). This can then be related to the number of INPs per litre of sampled air by:

where Vww is the volume in mL of water used to wash the filter, and Vair is the volume of air sampled through the filter in L. For the heat treatment tests, 0.75 mL of the filter washing waters was placed into a sealed Eppendorf tube, and heated to 95 °C for 1 hour. Mass loss from heating was determined gravimetrically and accounted for. Following heating, particles were resuspended in the Eppendorf tubes using a vortex mixer for 20 s prior to analysis via the μL-NIPI. Daily control freezing spectra were taken of the ‘pure’ MilliQ® water, to ensure that any background freezing on that day (due to impurity particles in the water) was diminishingly small in number relative to the number of INPs in the water after aerosol sampling. The pure water backgrounds are illustrated in Supplementary Information Fig. 1.

A principle source of uncertainty in the experiments stems from the representativeness of sampling of INPs into droplets from the bulk suspension. This is of particular importance at temperatures where only a minor fraction of droplets contains active ice-nucleating particles. At such temperatures, the observed number of INPs per droplet in the subset sample removed from the vial can vary from that in the population (i.e. the vial of water into which INPs were sampled). Confidence intervals for the population number of INPs per droplet are constructed using the variance scores interval from Barker67:

where µ(T) is the number of INPs per droplet, Zα/2 is the standard score at a confidence level α/2, which for a 95% confidence interval is 1.96.

Global aerosol model

The GLOMAP mode global aerosol model used here has been described in detail in Mann et al.68. The horizontal resolution of the model is 2.8° × 2.8°, and contains 31 pressure levels from the surface to 10 hPa. The surface level is about 60 m deep. The model uses wind, temperature and humidity fields from the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) from the year 2000 to 2001 in order to reach a steady-state aerosol distribution before running the model for the year 2001 to 2002. Further details of the model setup are given in Vergara-Temprado et al.6, but the major uncertainties in the model arise from uncertainties in the evolution of dust concentrations and aerosol microphysical processes69,70, along with the differences in the density of active sites for different types of K-feldspar71 and the effects of acid aging on the feldspar nucleating activity.

Back trajectory analysis

To examine the origin of air masses arriving at the rural site, 120 hr (5 day) air mass back trajectories arriving at 100 m were calculated using the NOAA HYSPLIT model v458 using data from the Global Data Assimilation System archive. Hourly back trajectories were calculated to coincide with the sampling times. In order to probe whether the 5 day back trajectories could account for INP observations at the site, each trajectory was assigned a value of Easterly, Westerly, Northerly or Southerly, depending on the major origin of the air mass. As indicated in Fig. 3, INP levels were not found to be strongly influenced by the major direction of the back trajectory.

Scanning electron microscopy and energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy

Details of the SEM-EDS analysis are provided in the supplementary information.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available in the University of Leeds repository at, https://doi.org/10.5518/330.

References

Boucher, D. O. et al. Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. (Cambridge University Press, 2013).

Vergara-Temprado, J. et al. Strong control of Southern Ocean cloud reflectivity by ice-nucleating particles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 115, 2687–2692 (2018).

DeMott, P. J. et al. Predicting global atmospheric ice nuclei distributions and their impacts on climate. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107, 11217–11222 (2010).

Herbert, R. J. R. J., Murray, B. J. B. J., Dobbie, S. J. S. J. & Koop, T. Sensitivity of liquid clouds to homogenous freezing parameterizations. Geophys. Res. Lett. 42, 1599–1605 (2015).

Atkinson, J. D. et al. The importance of feldspar for ice nucleation by mineral dust in mixed-phase clouds. Nature 498, 355–358 (2013).

Vergara-Temprado, J. et al. Contribution of feldspar and marine organic aerosols to global ice nucleating particle concentrations. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 17, 3637–3658 (2017).

Hoose, C. & Möhler, O. Heterogeneous ice nucleation on atmospheric aerosols: A review of results from laboratory experiments. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 12, 9817–9854 (2012).

DeMott, P. J. et al. Sea spray aerosol as a unique source of ice nucleating particles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 113, 5797–5803 (2015).

Wilson, T. W. et al. A marine biogenic source of atmospheric ice-nucleating particles. Nature 525, 234–238 (2015).

Ansmann, A. et al. Influence of Saharan dust on cloud glaciation in southern Morocco during the Saharan Mineral Dust Experiment. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 113 (2008).

Kanitz, T. et al. Contrasting the impact of aerosols at northern and southern midlatitudes on heterogeneous ice formation. Geophys. Res. Lett. 38, (2011).

Murray, B. J. J., O’Sullivan, D., Atkinson, J. D. D. & Webb, M. E. E. Ice nucleation by particles immersed in supercooled cloud droplets. Chem. Soc. Rev. 41, 6519–6554 (2012).

Schnell, R. C. & Vali, G. Atmospheric ice nuclei from decomposing vegetation. Nature 236, 163–165 (1972).

Schnell, R. C. & Vali, G. World-wide source of leaf-derived freezing nuclei. Nature 246, 212–213 (1973).

Schnell, R. C. & Vali, G. Biogenic ice nuclei: Part I. Terrestrial and marine sources. J. Atmos. Sci. 33, 1554–1564 (1976).

Creamean, J. M. et al. Dust and Biological Aerosols from the Sahara and Asia Influence Precipitation in the Western U.S. Science. 339, 1572–1578 (2013).

Morris, C. E. et al. Bioprecipitation: a feedback cycle linking Earth history, ecosystem dynamics and land use through biological ice nucleators in the atmosphere. Glob. Chang. Biol. 20, 341–351 (2014).

Möhler, O., DeMott, P. J., Vali, G. & Levin, Z. Microbiology and atmospheric processes: the role of biological particles in cloud physics. Biogeosciences 4, 1059–1071 (2007).

Vali, G. et al. Biogenic ice nuclei. Part II: Bacterial sources. J. Atmos. Sci. 33, 1565–1570 (1976).

Hoose, C., Kristjánsson, J. E. & Burrows, S. M. How important is biological ice nucleation in clouds on a global scale? Environ. Res. Lett. 5, 24009 (2010).

Phillips, V. T. J. et al. Potential impacts from biological aerosols on ensembles of continental clouds simulated numerically. Biogeosciences 6, 987–1014 (2009).

Ashworth, E. N., Kieft, T. L. & Vali, G. In Biological Ice Nucleation and Its Applications (eds Lee Jr, R. E., Warren, G. J. & Gusta, L. V.) 1–28 (American Phytopathological Society, 1995).

Kanji, Z. A. et al. In Meteorological Monographs Chapter 1, https://doi.org/10.1175/AMSMONOGRAPHS-D-16-0006.1 (American Meteorological Society, 2017).

Hill, T. C. J., DeMott, P. J., Conen, F. & Mohler, O. In Microbiology of aerosols (eds Delort, A.-M. & Amato, P.) 197 (2018).

Christner, B. C., Morris, C. E., Foreman, C. M., Cai, R. & Sands, D. C. Ubiquity of biological ice nucleators in snowfall. Science. 319, 1214 (2008).

Hara, K. et al. Variations of ice nuclei concentration induced by rain and snowfall within a local forested site in Japan. Atmos. Environ. 127, 1–5 (2016).

Christner, B. C. et al. Geographic, seasonal, and precipitation chemistry influence on the abundance and activity of biological ice nucleators in rain and snow. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 105, 18854 (2008).

Joly, M. et al. Quantification of ice nuclei active at near 0 C temperatures in low-altitude clouds at the Puy de Dôme atmospheric station. Atmos. Chem. Phys 14, 8185–8195 (2014).

Hiranuma, N. et al. A comprehensive laboratory study on the immersion freezing behavior of illite NX particles: A comparison of 17 ice nucleation measurement techniques. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 15, 2489–2518 (2015).

Garcia, E. et al. Biogenic ice nuclei in boundary layer air over two US High Plains agricultural regions. J. Geophys. Res. 117, D18209 (2012).

Huffman, J. A. et al. High concentrations of biological aerosol particles and ice nuclei during and after rain. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 13, 6151–6164 (2013).

Prenni, A. J. et al. Relative roles of biogenic emissions and Saharan dust as ice nuclei in the Amazon basin. Nat. Geosci. 2, 402–405 (2009).

Pratt, K. A. et al. In situ detection of biological particles in cloud ice-crystals. Nat. Geosci. 2, 398–401 (2009).

Zawadowicz, M. A., Froyd, K. D., Murphy, D. M. & Cziczo, D. J. Improved identification of primary biological aerosol particles using single particle mass spectrometry. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 17, 7193–7212 (2017).

Spracklen, D. V. & Heald, C. L. The contribution of fungal spores and bacteria to regional and global aerosol number and ice nucleation immersion freezing rates. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 14, 9051–9059 (2014).

Pummer, B. G. et al. Ice nucleation by water-soluble macromolecules. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 15, 4077–4091 (2015).

O’Sullivan, D. et al. The relevance of nanoscale biological fragments for ice nucleation in clouds. Sci. Rep. 5, 8082 (2015).

Knopf, D. A., Alpert, P. A. & Wang, B. The Role of Organic Aerosol in Atmospheric Ice Nucleation: A Review. ACS Earth Space Chem. 2, 168–202 (2018).

Fröhlich-Nowoisky, J. et al. Ice nucleation activity in the widespread soil fungus Mortierella alpina. Biogeosciences 12, 1057–1071 (2015).

Pummer, B. G., Bauer, H., Bernardi, J., Bleicher, S. & Grothe, H. Suspendable macromolecules are responsible for ice nucleation activity of birch and conifer pollen. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 12, 2541–2550 (2012).

Rangel-Alvarado, R. B., Nazarenko, Y. & Ariya, P. A. Snow-borne nanosized particles: Abundance, distribution, composition, and significance in ice nucleation processes. J. Geophys. Res. 120, 11,760–711,774 (2015).

O’Sullivan, D., Murray, B. J., Ross, J. F. & Webb, M. E. The adsorption of fungal ice-nucleating proteins on mineral dusts: A terrestrial reservoir of atmospheric ice-nucleating particles. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 16, 7879–7887 (2016).

Schnell, R. C. Kaolin and a Biogenic Ice Nucleant: Some Nucleation and Identification Studies. In IX Nucleation Conference 353–356 (1977).

Belosi, F. et al. Ground level ice nuclei particle measurements including Saharan dust events at a Po Valley rural site (San Pietro Capofiume, Italy). Atmos. Res. 186, 116–126 (2017).

Hill, T. C. J. et al. Sources of organic ice nucleating particles in soils. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 16, 7195–7211 (2016).

Conen, F., Morris, C. E., Leifeld, J., Yakutin, M. V. & Alewell, C. Biological residues define the ice nucleation properties of soil dust. Atmos. Chem. Phys 11, 9643–9648 (2011).

Zolles, T. et al. Identification of Ice Nucleation Active Sites on Feldspar Dust Particles. J. Phys. Chem. A 119, 2692–2700 (2015).

O’Sullivan, D. et al. Ice nucleation by fertile soil dusts: relative importance of mineral and biogenic components. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 14, 1853–1867 (2014).

Conen, F., Stopelli, E. & Zimmermann, L. Clues that decaying leaves enrich Arctic air with ice nucleating particles. Atmos. Environ. 129, 91–94 (2016).

Schnell, R. C. & Vali, G. Freezing nuclei in marine waters. Tellus 27, 321–323 (1975).

Petters, M. D. & Wright, T. P. Revisiting ice nucleation from precipitation samples. Geophys. Res. Lett. 42, 8758–8766 (2015).

Stopelli, E. et al. Predicting abundance and variability of ice nucleating particles in precipitation at the high-altitude observatory Jungfraujoch. Atmos. Chem. Phys 16, 8341–8351 (2016).

Prenni, A. J. et al. The impact of rain on ice nuclei populations at a forested site in Colorado. Geophys. Res. Lett. 40, 227–231 (2013).

Jones, A. M. & Harrison, R. M. The effects of meteorological factors on atmospheric bioaerosol concentrations–a review. Sci. Total Environ. 326, 151–180 (2004).

Wright, T. P., Hader, J. D., McMeeking, G. R. & Petters, M. D. High Relative Humidity as a Trigger for Widespread Release of Ice Nuclei. Aerosol Sci. Technol. 48, i–v (2014).

Wang, B. et al. Airborne soil organic particles generated by precipitation. Nat. Geosci. 9, 433–437 (2016).

Joung, Y. S. & Buie, C. R. Aerosol generation by raindrop impact on soil. Nat. Commun. 6, 6083 (2015).

Stein, A. F. et al. Noaa’s hysplit atmospheric transport and dispersion modeling system. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 96, 2059–2077 (2015).

Hoose, C., Kristjánsson, J. E., Chen, J.-P. & Hazra, A. A Classical-Theory-Based Parameterization of Heterogeneous Ice Nucleation by Mineral Dust, Soot, and Biological Particles in a Global Climate Model. J. Atmos. Sci. 67, 2483–2503 (2010).

Claquin, T., Schulz, M. & Balkanski, Y. J. Modeling the mineralogy of atmospheric dust sources. J. Geophys. Res. 104, 22243–22256 (1999).

Niemand, M. et al. A Particle-Surface-Area-Based Parameterization of Immersion Freezing on Desert Dust Particles. J. Atmos. Sci. 69, 3077–3092 (2012).

Soo, J.-C., Monaghan, K., Lee, T., Kashon, M. & Harper, M. Air sampling filtration media: Collection efficiency for respirable size-selective sampling. Aerosol Sci. Technol. 50, 76–87 (2016).

Lindsley, W. G. In NIOSH Manual of Analytical Methods (eds Ashley, K. & O’Connor, P. F.) 1–14 (Department of Health and Human Services, 2016).

Möhler, O. et al. The effect of organic coating on the heterogeneous ice nucleation efficiency of mineral dust aerosols. Environ. Res. Lett. 3, 25007 (2008).

Whale, T. F. F. et al. A technique for quantifying heterogeneous ice nucleation in microlitre supercooled water droplets. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 8, 2437–2447 (2015).

Vali, G. Quantitative Evaluation of Experimental Results an the Heterogeneous Freezing Nucleation of Supercooled Liquids. J. Atmos. Sci. 28, 402–409 (1971).

Barker, L. A Comparison of Nine Confidence Intervals for a Poisson Parameter When the Expected Number of Events is ≤5. Am. Stat. 56, 85–89 (2002).

Mann, G. W. et al. Geoscientific Model Development Description and evaluation of GLOMAP-mode: a modal global aerosol microphysics model for the UKCA composition-climate model. Geosci. Model Dev 3, 519–551 (2010).

Huneeus, N. et al. Global dust model intercomparison in AeroCom phase I. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 11, 7781–7816 (2011).

Mann, G. W. et al. Intercomparison and evaluation of global aerosol microphysical properties among AeroCom models of a range of complexity. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 14, 4679–4713 (2014).

Harrison, A. D. et al. Not all feldspar is equal: a survey of ice nucleating properties across the feldspar group of minerals. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 16, 10927–10940 (2016).

Acknowledgements

The authors are very grateful for the help and assistance of the team who operate the Leeds Research Farm, in particular George Sorensen. We thank the UK Met Office for providing data. The authors would like to acknowledge the European Research Council (MarineIce: 648661 and CryoProtect: 713664), the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EP/M003027/1) and the Natural Environment Research Council (NE/M010473/1) for funding this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.O’.S. designed the study, led the field/laboratory measurements and wrote the manuscript. M.A., M.D.T., A.D.H., G.C.E.P., M.A.H., A.S.M., F.C. and T.F.W. performed field and laboratory measurements in the study. J.V.T. ran the GLOMAP simulations used in the work. A.S.M. performed SEM-EDX analysis of samples. R.W., D.H. and I.T.B. supervised in the measurements and analysis. Z.C. assisted with determining the HYSPLIT analysis. B.J.M. and J.B.M.Q. oversaw the study and assisted with the preparation of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

O’Sullivan, D., Adams, M.P., Tarn, M.D. et al. Contributions of biogenic material to the atmospheric ice-nucleating particle population in North Western Europe. Sci Rep 8, 13821 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-31981-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-31981-7

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Annual cycle observations of aerosols capable of ice formation in central Arctic clouds

Nature Communications (2022)

-

Biodiversity loss and climate extremes — study the feedbacks

Nature (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.