Abstract

Targeted mutagenesis using CRISPR/Cas9 technology has been shown to be a powerful approach to examine gene function in diverse metazoan species. One common drawback is that mixed genotypes, and thus variable phenotypes, arise in the F0 generation because incorrect DNA repair produces different mutations amongst cells of the developing embryo. We report here an effective method for gene knockout (KO) in the hydrozoan Clytia hemisphaerica, by injection into the egg of Cas9/sgRNA ribonucleoprotein complex (RNP). Expected phenotypes were observed in the F0 generation when targeting endogenous GFP genes, which abolished fluorescence in embryos, or CheRfx123 (that codes for a conserved master transcriptional regulator for ciliogenesis) which caused sperm motility defects. When high concentrations of Cas9 RNP were used, the mutations in target genes at F0 polyp or jellyfish stages were not random but consisted predominantly of one or two specific deletions between pairs of short microhomologies flanking the cleavage site. Such microhomology-mediated (MM) deletion is most likely caused by microhomology-mediated end-joining (MMEJ), which may be favoured in early stage embryos. This finding makes it very easy to isolate uniform, largely non-mosaic mutants with predictable genotypes in the F0 generation in Clytia, allowing rapid and reliable phenotype assessment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Gene editing is now possible in a wide range of organisms by exploiting the molecular components of the CRISPR bacterial adaptive immune system1,2,3,4,5. The well-known SpCas9 protein from Streptococcus pyogenes acts as a sequence specific exonuclease6,7. Cas9 protein in a complex with a short guide RNA (sgRNA) stimulates RNA-DNA duplex formation between the sgRNA and a target sequence followed by a PAM motif (NGG for SpCas9), and then makes a double strand break (DSB) 3 or 4 bp upstream of the PAM motif 8. Gene editing per se is achieved during repair of the DSB caused by the Cas9/sgRNA complex. Small insertions or deletions can be introduced as a result of errors during DNA repair, while precise modifications can be obtained by homology-directed DNA repair with an exogenous DNA template9,10,11,12. Gene editing is thus strongly dependent on the activity of endogenous DSB repair machinery in the targeted cells.

Gene knockout (KO) induced by CRISPR/Cas9 has now been demonstrated in a wide range of metazoan species, including many for which classical genetic approaches are not feasible13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29. This is allowing researchers to address a wide range of questions, for instance in the fields of ecology, evolution and biodiversity, that would be difficult to tackle in the common genetics model organisms such as Drosophila or zebrafish.

A common approach for CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene KO is to introduce the Cas9/sgRNA RNP complex, or DNA/RNA encoding its components, into the egg cytoplasm by microinjection. The resultant embryos usually comprise a “mosaic” of different genotypes resulting from independent mutations in different cell linages. A pitfall of this approach is thus that phenotypes vary between embryos depending on the mix of induced genotypes, even when the overall mutation efficiency is high, for instance if some cell populations have in-frame mutations with little or no functional consequence for the protein produced. In mammalian embryos, the frame-shift mutations can be favoured by computationally choosing sgRNAs based on the presence of sequence microhomologies flanking to the DSB site30,31. This strategy relies on the prevalence of microhomology-mediated end-joining (MMEJ) repair mechanism in mammalian embryos, which promotes frequent deletions between these sites17,21,30. In Xenopus another strategy used to create non-mosaic F0 heterozygotes is to inject Cas9/sgRNA into oocytes before meiotic maturation and fertilization, thus favouring mutation before cleave divisions begin32.

Here we report a highly efficient gene KO method for the hydrozoan jellyfish Clytia hemisphaerica, which exploits particularities both of the DSB repair pathway deployment during embryogenesis, and its characteristic hydrozoan life cycle. In Clytia the fertilized egg develops in three days into a planula larva, which then metamorphoses to generate a quasi-immortal, vegetatively propagating colony of connected polyps. Sexually reproducing jellyfish bud continuously from specialised polyps of the colony (Fig. 1)33,34. We achieved highly efficient biallelic mutation for two endogenous Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP) genes by Cas9/sgRNA RNP injection into the egg. Similar success was achieved for the CheRfx123 gene, the single Clytia counterpart of vertebrate Rfx1, 2 and 3 genes that play conserved roles for cilia formation in bilaterians and observed sperm flagella defects in jellyfish generated from F0 polyps. Cas9/sgRNA injected embryos and larvae were mosaic, but we uncovered an unexpected enrichment phenomenon during the life cycle such that mutant jellyfish had very low mosaicism with predominant deletions between microhomologies. By exploiting this unique phenomenon, it is possible to make non-mosaic Clytia mutant polyps and jellyfishes in the F0 generation.

Life cycle of Clytia hemisphaerica. Cas9 RNP is injected into unfertilized eggs, which develop to planula larvae in 3 days after fertilization. Planulae undergo metamorphosis to make polyp colonies, which propagate vegetatively and thus constitute a genetic resource convenient to maintain and replicate. The colony releases juvenile jellyfish, which will grow to sexual maturity in a few weeks and spawn every day. The minimum life cycle is 2~3 months.

Results

Highly efficient biallelic gene KO by CRISPR/Cas9 in Clytia

To test CRISPR/Cas9 knockout protocols in Clytia we performed pilot studies on genes predicted to have easily assessible phenotypes, the endogenous GFP genes and a Clytia orthologue of the RFX family of transcription factors, CheRfx123. Like the hydrozoan jellyfish Aqueora victoria35 from which GFP was originally isolated, Clytia larvae and medusa produce green fluorescent proteins from endogenous GFP genes, providing convenient targets for the development of gene KO approaches. Four Clytia GFP genes (CheGFP1-CheGFP4) with distinct expression profiles have been reported36. In planula larvae, CheGFP1 expressed from the zygotic genome produces a band of green fluorescence in the lateral ectoderm, while maternal CheGFP2 protein, targeted to egg mitochondria, accounts for weaker, uniform expression. CheGFP3 and CheGFP4, in contrast, are expressed predominantly in adult cell types, with little or no mRNA detectable at embryonic and larval stages. We thus selected CheGFP1 as an ideal target to test gene KO in Clytia. NLS-tagged SpCas9 (Cas9) protein and single guide RNA (sgRNA) were pre-assembled and microinjected into eggs prior to fertilisation. Out of three sgRNAs tested, GFP1n4 provoked a loss of GFP at the planula stage (Fig. 2A). CheGFP1 fluorescence was completely or almost completely abolished in the planula larvae 3 days after fertilisation when 4 µM or higher Cas9 RNP concentration was microinjected (Fig. 2B). Remaining uniform and faint green fluorescence in CheGFP1 “complete loss” embryo (Fig. 2A) probably reflects the presence of residual maternal CheGFP2. Some specimens in the high Cas9 RNP condition showed sporadic and weak CheGPF1 signal, which was often in longitudinal stripes of cells (arrowhead in “sporadic” Fig. 2A), suggesting each line was clonally derived from a single blastomere at the blastula stage. Another sgRNA, GFP1n1, did not alter CheGFP1 fluorescence in planula, even though it induced mutations at high rates (9/13 at 3 µM). To generate Clytia strains lacking GFP expression during embryonic development as a resource for future studies using exogenous EGFP or EYFP reporters, we targeted the two maternal/embryonic GFP genes CheGFP1 and CheGFP2 simultaneously by injecting a mixture of two sgRNAs (GFP1n4 and GFP2n7) and Cas9. 3 days after injection the planulae were induced to metamorphose into primary polyps, which were then reared to give F0 polyp colonies generating jellyfish 1–2 months after injection. When high concentrations of Cas9 RNP were used, none of the eggs collected from F0 jellyfish showed CheGFP2 expression (Fig. 2C). 63.2% (n = 669) of F1 larvae obtained by crossing male and female F0 founder jellyfish lacked CheGFP1/CheGFP2 fluorescence (Fig. 2D). This result shows highly efficient mutation in the jellyfish germline. We were able to establish 6 GFP mutant colonies (2 males and 4 females, CheGFP1−/−; CheGFP2−/−). No visible phenotype was detected during embryogenesis in the GFP-free F1 generation, except for the loss of the green fluorescence.

Highly efficient gene KO by CRISPR/Cas9 in Clytia hemisphaerica. (A) Classification of endogenous green fluorescence depletion phenotypes in Cas9/sgRNA(GFP1n4) RNP-injected 3-day old planula larvae. “wildtype” shows typical endogenous green fluorescence, mainly from CheGFP1 gene. In “complete loss” no green signal was observed except for uniform maternal GFP signal. In “sporadic”, groups of weakly GFP positive cell form patches (arrowhead), each probably descended from single cells in which CheGFP1 was mutated only after the onset of transcription. An embryo was classified as having “reduced” green fluorescence if the signal was significantly reduced but still showed the typical regional expression pattern. (B) Population of phenotypes described in (A) for each Cas9 RNP concentration tested. (C) Maternal CheGFP2 fluorescence in eggs released from wildtype and CheGFP1/ CheGFP2 double KO F0 jellyfish. (D) GFP fluorescence in a wildtype planula (left) and in F1 planulae from male and female CheGFP1/CheGFP2 double KO founder jellyfish, which were either completely GFP free (CheGFP1−/− centre) or almost identical to wildtype (CheGFP1+/− or CheGFP1+/+, right). In both cases, functional maternal CheGFP2 protein was absent according to (C). (E~G) Sperm motility defect in sperm produced CheRfx123 KO F0 jellyfish observed by speed microscopic movies for wildtype (N = 6) and CheRfx123-KO (N = 8) sperms. (E) Swimming velocity (***p < 0.001 Welsh’s t-test). (F) An example of sperm flagellar bending forms by time. 20 bending forms of a single sperm were picked out at every 5 milliseconds (0.1 seconds in total) and superimposed. Blue dots show the position of sperm head. CheRfx1 KO sperm oscillated but barely translocated. (G) Flagellar length (**p < 0.01 Welsh’s t-test). (H) An example of bending curvature of sperm flagella, superimposed for 20 bending forms with 5 milliseconds of interval. The x-axis is the distance along the flagellum from its base and y-axis is for the curvature at the point indicated by µm−1, which is reciprocal of the radius of the circle that fits a curve. In CheRfx1 KO sperm, the wave of sperm bending did not propagate long distance from the base of flagellum.

Another pilot target gene was CheRfx123, a Clytia orthologue of the Rfx (Regulatory Factor X) family of genes that encode transcription factors playing evolutionary conserved roles for ciliogenesis in bilaterians37. Vertebrates generally have three paralogous Rfx genes Rfx1, 2 and 3. Rfx2 and Rfx3 mutants showed various defects in cilia (dysfunction of motile cilia, fewer or truncated motile cilia,38,39,40 and in the nematode C. elegans mutants of the Rfx gene DAF-19 lack all sensory neuron cilia41. We reasoned that CheRfx123 mutants would be useful for addressing the role of cilia in embryonic and larval development, during which the alignment of monociliated ectoderm cells becomes coordinated along the developing body axis42, and might also provide a useful resource to generate non-motile embryos for microscopy. Animals injected with Cas9/sgRNA(Rfxn1) RNP showed no visible phenotype of the motile cilia in the planula ectoderm or in the jellyfish gonad ectoderm (data not shown), despite high efficiency of biallelic mutation (see following section). Strikingly, however, F0 male jellyfish were completely sterile and showed a clear defect in the sperm motility (Fig. 2E,F). Sperm locomotion was significantly slower. Movie image analysis showed that flagella bending did not propagate more than 20 µm from the base of the flagella (Fig. 2H). The length of the sperm flagella also seemed significantly reduced compared to wild type (Fig. 2G). No fertilisation was achieved with the sperm from CheRfx123-KO F0 jellyfish, indicating complete absence of any functional spermatozoids.

Most Cas9 induced deletions in Clytia polyps and jellyfish are between microhomologies

From genotype analysis at the F0 polyp or jellyfish stages or in the F1 generation, we noticed that one or two specific deletions always dominated (Fig. 3A). For example, 13 out of 20 randomly sequenced CheRfx123 PCR clones from four polyp colonies (5 clones/colony) had an identical 5 bp deletion, and otherwise had an insertion in addition to the 5 bp deletion (6/20). All 24 clones from six jellyfishes (4 clones/jellyfish) had the same 5 bp deletion. A similar low diversity of mutations in F0 polyps and in the F1 generation was observed with all target sgRNAs tested for CheGFP1 and CheGFP2 genes using the same injection conditions (Fig. 3B). Similarly, mutations induced at the 3′-end of Che-β-catenin coding region consisted only of either 5 or 25 bp deletions when examined in F0 polyp colony (Fig. 3B). Strikingly, sequence analysis revealed that for all genes tested these dominant deletions had taken place between two identical 2 to 5 bp sequences, so called microhomologies, lying on either side of the double strand break (DSB) (Fig. 3). We will refer to this type of deletion as microhomology mediated (MM) deletions in this work. Previous studies suggested that MM deletions are caused by DSB repair by the MMEJ pathway43,44. To investigate the basis of the prevalence of the MM deletions, we focused our analyses on the CheRfx123 gene, in which the dominant 5 bp deletion can be detected by restriction enzyme digestion. To test Cas9/sgRNA-dose dependence, we injected low (2 µM) and high (8 µM) concentrations of Cas9 RNP into eggs and established several polyp colonies for each condition. After 4 months of culture, genomic DNA was extracted from 5 randomly selected polyp colonies and the genotypes within each colony were examined. Digestion of PCR products amplified from the polyp colony by restriction enzymes AatII and BceAI, which selectively cut wildtype and the 5 bp MM deletion respectively, showed that 3 out of 5 F0 colonies from the high Cas9 RNP condition (8 µM) were uniformly comprised of cells with the 5 bp MM deletion (Figs 4A,B and S2). No uncut PCR product was detectable by BceAI, indicating that virtually 100% of CheRfx123 copies in these colonies had MM deletion. The other two colonies were mosaic, showing 9% and 56% copies of the MM deletion. At lower concentration of Cas9 RNP, KO efficiency was still high. Three colonies still showed 100% KO efficiency and the remaining two had at least 79% efficiency. However, in contrast to the injections at high Cas9 RNP concentration, no MM deletion could be detected in low Cas9 RNP condition in 4 out of 5 colonies, with the fifth colony showing 49% MM deletion.

Prevalence of MM deletion in polyp and jellyfish stages. Mutation and their frequencies observed by Sanger sequencing of PCR clones from polyp and jellyfish stages are indicated. Complete or highly prevalent MM deletions were observed in all 6 targets from 4 genes. sgRNA sequence is underlined and PAM motif is represented in bold. Left microhomology sequences are indicated by magenta characters. The magenta arrow and cyan box indicate respectively, the predicted double-strand break position and deleted sequence in the mutant. Stage and frequency are indicated on the right.

Creation of non-mosaic CheRfx123 KO colonies in F0 generation at high dose of Cas9 RNP. (A,B) Estimation of the genotype population by digestion of PCR products with restriction enzymes, AatII (top gel) and BceAI (bottom gel), that cut wildtype sequence and the 5 bp MM deletion respectively. (A) Agarose gel electrophoresis of digested PCR products. AatII-resistant bands showed nearly complete biallelic mutation at both concentrations. Complete BceAI digestion of PCR product from three out of five colonies obtained after injection of 8 µM Cas9 showed that they uniformly consisted in the 5 bp MM deletion. The analysis was repeated for 5 independent colonies for each condition. (C) An example of sequence chromatogram for direct sequencing of PCR product, showing uniform wildtype colony (top), uniform MM deletion colony (middle, at high Cas9 RNP concentration) and a mosaic mutant colony (bottom, at low Cas9 RNP concentration). The DSB site is indicated by a triangle. The microhomology sequences are surrounded by boxes. The PAM motif and AatII/BceAI site used in restriction enzyme analysis are indicated by bars. (D) Estimation of frequency of indel by sizes (lengths) by TIDE calculations. The estimation in the 5 different polyp colonies (y-axis) for low (2 µM) and high (8 µM)Cas9 RNP conditions. Deletions and insertions are to the left and right of the wild type (0 bp indels, grey) in x-axis. The 5 bp deletion corresponding MM deletion is marked by arrows (green columns).

Uniform genotypes in the three colonies generated from high-dose Cas9 injections were visible in the chromatogram of direct sequencing of the PCR products (Fig. 4C). TIDE (Tracking of Indels by DEcomposition) analysis, which breaks down the mixed indel compositions from sequence trace data45, confirmed that polyp colonies derived from high concentration Cas9 RNP injections were dominated by the 5 bp MM deletion (Fig. 4D). In contrast, mutations were more diverse in polyp colonies derived from low concentration Cas9 RNP injection, and the MM deletion was not predominant (Fig. 4D). These analyses demonstrate that non-mosaic and homozygous Clytia mutant polyp colonies can be made in a single generation simply by injecting high concentrations of Cas9/sgRNA RNP, and that MM deletions are favoured in these conditions.

MM deletions are prevalent at the planula stage and become enriched in polyps

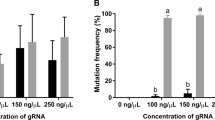

To address carefully how and when MM deletions took place, we tested the timing of mutagenesis after Cas9 RNP injection by digesting target PCR products by AatII. Following injection of Cas9 RNP at high concentrations (8 µM), a large proportion of the target copies (average 87%) were modified as early as 9 hours after injection, and virtually all target copies (98%) were modified within 24 hours (Fig. 5A). In comparison indel rates induced by the lower Cas9 concentration (2 µM) were on average 42% at 9 hours and 80% at 24 hours. The timing of mutagenesis was thus Cas9 RNP dose-dependent. In parallel, we examined by restriction enzyme digestion and TIDE analysis the frequency of overall mutations and MM deletions induced by different Cas9 RNP concentrations at the 3-days-old planula stage, when they become ready to undergo metamorphosis into polyps (Fig. 5B–D, and S2). As assessed by AatII digestion, 93% mutants using 2 µM Cas9 RNP and no wildtype CheRfx123 copies was detectable when 4 µM or higher Cas9 RNP concentration was used (Fig. 5B,C). TIDE analysis similarly detected few or no wildtype CheRfx123 copies following injection of Cas9 RNP at 4 µM or higher (Fig. 5D). This assay generally estimated higher wildtype frequencies than restriction enzymes, for example 12% by TIDE versus 6% by AatII digestion in larvae generated by injection of 2 µM Cas9 RNP). The estimated frequency of MM deletion was also different between TIDE analysis and digestion with restriction enzymes (58% vs 33% respectively using 8 µM Cas9 RNP). The rate of MM deletion relative to overall mutations was, however, clearly Cas9-dose dependent with both analyses (Figs 5C,D and S1). To explain this clear trend, we hypothesised that MM deletions might be favoured at the earlier times during development. Comparison of MM deletion frequency between the earlier and later stages did not, however, reveal any temporal shift during development (Fig. 5E).

Target sequence mutation rate and MM deletion frequency after injection with different doses of Cas9/sgRNA RNP. (A) The time course of CheRfx123 KO efficiency after Cas9/sgRNA injection (2 µM and 8 µM). KO efficacy was measured by AatII digestion from three independent experiments for each condition. (B) Agarose gel electrophoresis of AatII/BceAI digested PCR products to measure KO efficiency and the rate of MM deletion in 3-day planula larvae. (C,D) Population of genotypes in Cas9-injected 3-day planulae estimated by restriction enzyme digestion (C) and by TIDE (D) of the PCR products. Average of three independent injections. Concentration dependency of MM deletion frequency over all detected mutation was confirmed by 1-way ANOVA with p = 0.00116 for (C) and p = 2.75e-05 for (D). wt: grey, MM deletion green other brown. Numbers on the bar indicate average mutation rate (%). Numbers on above (D) are coefficient of determination (R2) of non-linear least square analysis used for TIDE calculation, indicating how well the estimated fits to the observed chromatograms. In practice, it matches to the sum of mutated and unmutated DNA sequences. (E) Time-course observation of MM deletion frequency from 3 to 24 hours after injection with low concentration (2 µM light blue) and high concentration (8 µM dark green) of Cas9 RNP in three independent experiments. The measurement was not reliable at 3 hpf with lower Cas9 RNP concentration due to very low mutation rate, which are thus indicated by the dotted line.

Finally, to understand the relationship between the MM frequency observed at planula stages and later polyp colonies, we compared genotype shift between these stages for the same set of mutagenesis experiments (Fig. 6). Sanger sequencing confirmed that MM deletion is already slightly more common than other mutations in the mosaic planula larvae, and then these then become highly dominant in F0 planula and jellyfish stages (Fig. 6A). MM deletion was gradually enriched as the life cycle progressed. Systematic analysis using TIDE following high concentration Cas9 RNP injections confirmed this result (Fig. 6B). In contrast, following low concentration Cas9 RNP injections, MM deletions were slightly less frequent in planula larvae and then disappeared from the colony. This result suggests that polyp-forming stem cells, which are only a small part of planula larvae, have different mutation profiles as compared to somatic cells. The stem cell may therefore be highly sensitive to Cas9 RNP dose to cause the MM deletion.

Increasing prevalence of MM deletion from planula to polyp/jellyfish stage in CheRfx123 gene. Mutations observed by Sanger sequencing of PCR clones from different stages. Bold and italic represent nucleotide residues conserved with wildtype and insertion respectively. (A) deletion is indicated with a hyphen. Numbers indicate the frequency of identical genotype in each sequencing set. The dataset is from the same series of the injection as Figs 2 and 3. (B) TIDE breakdown of mutant genotype population analysed in 3-dayold planula larvae from separate 3 injections and 5 individual colonies of polyp 4-months old colonies after injection of high (top) and low (bottom) Cas9-RNP concentration. The dataset is from the same series of injections as Figs 4 and 5.

Discussion

We demonstrated that gene KO using CRISPR-Cas9 is highly efficient and effective in the hydrozoan Clytia hemisphaerica, as previously reported in many other metazoans. Importantly, it is feasible in Clytia to generate a nearly non-mosaic mutant polyp colony in the F0 generation. When microinjecting high concentrations of Cas9 RNP, one or two deletions that occur specifically between pairs of sequence microhomologies become enriched in the polyp colony. The advantages of this low-mosaicism in F0 animals was well illustrated by the CheRfx123-KO, which showed a sperm motility defect and thus was sterile. It is therefore feasible in Clytia to rapidly test the role of genes that are critical for gametogenesis and early embryonic development. The relatively short life cycle (2~3 months) of Clytia also allows a more standard genetic approach as demonstrated here by generating GFP1/GFP2 double KO in F1. The vegetative growth of the polyp colony makes Clytia a unique genetic model animal. The mutant colonies created by our approach, including weakly-mosaic F0 colonies, can in principle, like wild-type colonies, be maintained for at least five to ten years simply by daily feeding with Artemia salina larvae. This approach is particularly useful for functional studies of genes involved in reproduction46. The mutant colonies can be replicated by transplanting polyps to new colony plates. Clytia mutant strains are therefore very easy to share in the research community.

In most animal species, the type of mutation induced by Cas9 RNP is variable, and highly mosaic in the mutant F0 generation44. In Clytia, following injection of low doses of Cas9 RNP, the mutations accumulated relatively slowly and a broad spectrum of mutations was detected both in planula and polyp stages. In these conditions, functional characterization of gene KO animals would require raising F0 medusae to sexual maturity and crossing to select mutant F1 animals. In contrast, following injection of high doses of Cas9 RNP, only one or two MM deletion were predominant already at the embryonic stage and polyp colonies with very low mosaicism were generated for all 4 genes tested (Fig. 7). The phenotypic consequences of gene knockout could thus already be examined in the F0 generation. A similar bias towards MM deletions has been reported in mammalian cultured cells, the C. elegans germ line and in zebrafish21,30,44,47,48. Our analysis of published sequence data from CRISPR/Cas9 or TALEN-mediated gene knockout in various metazoan embryos also revealed frequent MM deletion (Fig. S2). Such MM deletions are most likely caused when the DSBs are repaired by MMEJ, a DSB pathway that is less well known than the classic non-homologous end-joining (NHEJ) pathway and the homologous recombination repair pathway (HR).

A scenario explaining how MM deletion could become dominant in polyp colonies generated from mosaic planula larvae. As polyp colonies grow in vegetative manner, massive proliferation of founder cells occurs. If MMEJ pathway is favoured in putative founder stem cells, resulting in the creation of MM deletions, these will become dominant in the polyp colony, from an initially mosaic planula larvae.

MMEJ may play a particularly important role during metazoan embryogenesis. Mutant zebrafish in which the key MMEJ pathway component polQ is defective become extremely sensitive to double strand breaks caused by Cas9 injection or ionizing radiation47. It is thus becoming clear that MMEJ is not a simple backup mechanism for NHEJ. Interestingly NHEJ pathway genes are largely missing in the genome of a pelagic tunicate Oikopleura dioica, which exhibits particularly high genome plasticity49. The role NHEJ generally plays in metazoan may be at least partly substituted by MMEJ in this species, contributing to genomic instability. Little is however known about the biological significance of MMEJ. Clytia can be an interesting research model to study the role of MMEJ during embryogenesis and in polyp growth, in particular during stem cell maintenance. Understanding MMEJ pathway is also important for future development of insertional gene editing50,51,52, which has not been successful so far in Clytia. The pattern of induced MM deletion seems different from other species. In Clytia, short (2~10 bp) MM deletion are frequently observed. A systematic survey for the induced mutation pattern will facilitate predictions of the dominant genotype, which may be different from predictions proposed in vertebrates30. Deep sequencing of mixed target amplicons for a large number of different sgRNAs will provide better understanding of the preferred MM deletions in Clytia embryonic cells44.

The key but as yet unexplained parameter allowing quasi non-mosaic F0 mutant generation in Clytia was the high Cas9 RNP condition. MM deletion occurred in a Cas9 RNP concentration dependent manner during embryogenesis. Our initial hypothesis was that MMEJ pathway activity could be high in the very early stages of the Clytia embryogenesis such as cleavage or blastula stages. A high dose of Cas9 RNP would increase the mutagenesis rate and thus more DSBs would be repaired at earlier stages by MMEJ. We however detected no stage specific preference of MM deletion with our dataset. MM deletion was more strongly favoured using high rather than low Cas9 RNP concentrations during early embryogenesis up to 24 hours after injection (Fig. S1E). It is thus more likely that Cas9 concentration affects DNA repair choice rather through cell-intrinsic factors such as the timing of DSB along the cell cycle. For example NHEJ and MMEJ are favoured in G1 phase while homologous recombination (HR) is favoured in S/G2 phase when repair templates are available53,54,55,56,57,58.

MM deletion enrichment in the F0 polyps or jellyfish contrasted with the mosaicism detected at planula stage. The degree of mosaicism greatly reduced between planula and polyp stages (see Fig. 6) even using the low concentration Cas9 RNP. This suggests a stochastic mechanism may be at least partly involved in the reduction of mosaicism. For example, a relatively small number of founder cells may support the polyp colony growth and any mutation generated randomly in these cells will become dominant. This mechanism however does not explain why MM deletions disappear from the polyp colonies using the low concentration Cas9 RNP protocol. Alternatively, or in addition to this, it is possible that MMEJ repair is strongly favoured in the stem cells using the high concentration Cas9 RNP protocol (Fig. 7). It is also possible that stem cells are lost if frequent DSB is repaired by the NHEJ pathway. Currently we lack a reliable method to identify stem cells from Clytia and examine the mutations that they carry. Multipotent or pluripotent stem cells called interstitial cells (i-cells) have been identified in other hydrozoans such as Hydra and Hydratinia echinata59,60 which are required for their regeneration capacity and vegetative growth. In Hydra, i-cells will give rise to neurons, nematocysts, gland cells and germline cells, while epidermal and gastrodermal epithelial cells self-renew independently. I-cells have also been identified in Clytia embryos and jellyfish based on the gene expression profile61. The DNA repair mechanisms and their regulation in Clytia stem cells need to be addressed, as well as further characterisation of stem cell populations in Clytia during embryogenesis and in the polyp colony.

There are several intriguing biological questions that could be addressed using Clytia as a model animal. We are now able to test the molecular basis of jellyfish behaviour, physiology, ecology and impact on environment. A part of the method established here has been already employed to reveal the role of Opsin9 gene for light-induced oocyte maturation control46. Physiological roles of GFP genes are to be further tested. GFP was identified in a hydrozoan jellyfish Aqueora victoria as a bioluminescence protein and several biological roles have been proposed for this protein36,62,63. It receives energy from Ca2+-activated photo protein Aequorin (Clytin) protein by BRET (bioluminescence resonance energy transfer) then emits bioluminescence, which may be used as a glowing lure for attracting prey in the dim deep sea environment. The presence of GFP in eggs and non-predatory planula suggested the role of green bioluminescence as a camouflage tool by counter illuminating at sea surface. Alternatively the capacity of UV absorbance of GFP itself may be used as UV protection64. These hypotheses can now be tested with our CheGFP1/CheGFP2 mutants in a condition modelling their natural habitat. Inactivation of CheGFP3 and CheGFP4 genes may also be necessary to address the biological function of GFP genes in the jellyfish stage.

In addition, Clytia may be a useful model for cell biology and development studies and provide an alternative to classical genetics models. An example is the CheRfx123 mutant that revealed the role of Rfx protein in sperm flagella. In vertebrates Rfx1~Rfx4 are expressed in developing spermatocytes and spermatids65. Mouse mutants of the Rfx genes show global defects in spermatogenesis but the mechanisms were not clear66. The CheRfx123 mutant showed for the first time the involvement of Rfx in sperm flagella formation and suggest an evolutionary conserved role for Rfx in cilia/flagella formation in metazoans. Clytia can be a useful model for studying genes that play a critical role in in early embryogenesis or reproduction and which may be otherwise difficult to investigate in other species because of mutant lethality. Our approach does not require crossing founder animals to make homozygous mutants, exploiting the prevalence of MM deletion and vegetatively growing mutant polyp colonies as demonstrated in this work.

Materials and Methods

Animal culture

Wild type laboratory strains of Clytia hemisphaerica Z4B (female) and Z10 (male) were used in this work33. All stages are maintained at 19~21 °C in artificial sea water (RedSea salt) dissolved to 37‰ with appropriate water circulation for the jellyfish stage. Artemia salina nauplii larvae (1~4 days after hatching) were used for daily feeding.

Microinjection of Cas9/sgRNA

Cas9 protein was synthesized as described previously67. The template vector small guide RNA (sgRNA) was constructed by cloning oligonucleotides into pDR27422. sgRNA was synthesized using Mega Shortscript T7 kit (ThermoFisher Scientifique) then purified with ProbeQuant G-50 column (GE healthcare) and ethanol precipitation. The sgRNA was dissolved into distilled water at 80 µM. sgRNA sequences are indicated in the Fig. 3. Purified Cas9 protein was diluted in Cas9 buffer (10 mM Hepes, 300 mM KCl). sgRNA was added to Cas9 protein in excess, up to 1:2 of Cas9:sgRNA prior the injection and incubated for 10 minutes at room temperature. The final concentration was adjusted to 1.0 to 8.0 µM of Cas9 protein. No visible toxicity was observed in embryos injected with up to 30 µM Cas9/sgRNA. The solution was centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 10 minutes at room temperature, and approximately 3% egg volume injected into eggs before fertilization (Fig. 1).

Inducing metamorphosis and establishing polyp colonies

Embryos were cultured to the planula larva stage in Millipore filtered sea water (MFSW) at 18 °C. Metamorphosis was induced at 3 or 4 days after injection by transferring 20~100 larvae in 4~5 ml MFSW containing 1 µg/µl synthetic peptide (GNPPGLW-amide, Genscript) spread on a double-width glass slide (75 × 50 mm) and incubating for up to 1 days. Metamorphosing primary polyps fixed on the glass were then transferred to aquariums maintained at 20 °C (favouring male colony development) or 24 °C (favouring female)68.

Microscopic analysis

GFP fluorescence was observed with Olympus BX-51 microscope and Leica DFC310-FX CCD imager, with a fixed exposure condition for each series of imaging. Sperm motility was filmed at 200 frames per second. Flagella curvatures and swimming velocity were measured using image analysis software BohBoh (Bohboh Soft, Tokyo, Japan).

Estimating knockout efficiency and genotyping

Genomic DNA was extracted using DNeasy blood/tissue extraction kit (Qiagen) from at least 50~500 3-day old planulae from a single injection for each condition or the entire colonies containing at least 20 polyps from each F0 colony grown on a 50 mm × 75 mm slide. Target sequences were amplified by PCR using Phusion DNA polymerase. The list of PCR primers used is in supplementary text. KO efficiency was first estimated to select effective sgRNAs for each target gene by restriction enzyme assay or by TIDE analysis45. Alternatively, the PCR products cloned into pGEM-Teasy vector were sequenced. To estimate mutation efficiency for the CheRfx123 gene (sgRNA: Rfxn1) we used a restriction enzyme AatII (NEB), which cuts only wild type sequence. Similarly, BceAI was used to detect the 5 bp MM deletion obtained with sgRNA Rfxn1 target sequence.

References

Mojica, F. J. M., Díez-Villaseñor, C., García-Martínez, J. & Soria, E. Intervening sequences of regularly spaced prokaryotic repeats derive from foreign genetic elements. J. Mol. Evol. 60, 174–182 (2005).

Pourcel, C., Salvignol, G. & Vergnaud, G. CRISPR elements in Yersinia pestis acquire new repeats by preferential uptake of bacteriophage DNA, and provide additional tools for evolutionary studies. Microbiology (Reading, Engl.) 151, 653–663 (2005).

Hsu, P. D., Lander, E. S. & Zhang, F. Development and applications of CRISPR-Cas9 for genome engineering. Cell 157, 1262–1278 (2014).

Doudna, J. A. & Charpentier, E. Genome editing. The new frontier of genome engineering with CRISPR-Cas9. Science 346, 1258096–1258096 (2014).

Lander, E. S. The Heroes of CRISPR. Cell 164, 18–28 (2016).

Gasiunas, G., Barrangou, R., Horvath, P. & Siksnys, V. Cas9-crRNA ribonucleoprotein complex mediates specific DNA cleavage for adaptive immunity in bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109, E2579–86 (2012).

Jinek, M. et al. A programmable dual-RNA-guided DNA endonuclease in adaptive bacterial immunity. Science 337, 816–821 (2012).

Garneau, J. E. et al. The CRISPR/Cas bacterial immune system cleaves bacteriophage and plasmid DNA. Nature 468, 67–71 (2010).

Cong, L. et al. Multiplex genome engineering using CRISPR/Cas systems. Science 339, 819–823 (2013).

Mali, P. et al. RNA-guided human genome engineering via Cas9. Science 339, 823–826 (2013).

Sander, J. D. & Joung, J. K. CRISPR-Cas systems for editing, regulating and targeting genomes. Nat. Biotechnol. 32, 347–355 (2014).

Wang, H., La Russa, M. & Qi, L. S. CRISPR/Cas9 in Genome Editing and Beyond. Annu Rev Biochem 85, 227–264 (2016).

Endo, M., Mikami, M. & Toki, S. Biallelic Gene Targeting in Rice. Plant Physiol. 170, 667–677 (2016).

Ni, W. et al. Efficient gene knockout in goats using CRISPR/Cas9 system. PLoS ONE 9, e106718 (2014).

Cho, S. W., Lee, J., Carroll, D., Kim, J.-S. & Lee, J. Heritable gene knockout in Caenorhabditis elegans by direct injection of Cas9-sgRNA ribonucleoproteins. Genetics 195, 1177–1180 (2013).

Jao, L.-E., Wente, S. R. & Chen, W. Efficient multiplex biallelic zebrafish genome editing using a CRISPR nuclease system. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110, 13904–13909 (2013).

Li, D. et al. Heritable gene targeting in the mouse and rat using a CRISPR-Cas system. Nat. Biotechnol. 31, 681–683 (2013).

Gilles, A. F., Schinko, J. B. & Averof, M. Efficient CRISPR-mediated gene targeting and transgene replacement in the beetle Tribolium castaneum. Development 142, 2832–2839 (2015).

Sasaki, H., Yoshida, K., Hozumi, A. & Sasakura, Y. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene knockout in the ascidian Ciona intestinalis. Dev Growth Differ 56, 499–510 (2014).

Martin, A. et al. CRISPR/Cas9 Mutagenesis Reveals Versatile Roles of Hox Genes in Crustacean Limb Specification and Evolution. Curr Biol 26, 14–26 (2016).

Wang, H. et al. One-step generation of mice carrying mutations in multiple genes by CRISPR/Cas-mediated genome engineering. Cell 153, 910–918 (2013).

Hwang, W. Y. et al. Efficient genome editing in zebrafish using a CRISPR-Cas system. Nat. Biotechnol. 31, 227–229 (2013).

Li, W., Teng, F., Li, T. & Zhou, Q. Simultaneous generation and germline transmission of multiple gene mutations in rat using CRISPR-Cas systems. Nat. Biotechnol. 31, 684–686 (2013).

Paix, A., Folkmann, A., Rasoloson, D. & Seydoux, G. High Efficiency, Homology-Directed Genome Editing in Caenorhabditis elegans Using CRISPR-Cas9 Ribonucleoprotein Complexes. Genetics 201, 47–54 (2015).

Square, T. et al. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated mutagenesis in the sea lamprey Petromyzon marinus: a powerful tool for understanding ancestral gene functions in vertebrates. Development 142, 4180–4187 (2015).

Blitz, I. L., Biesinger, J., Xie, X. & Cho, K. W. Y. Biallelic genome modification in F(0) Xenopus tropicalis embryos using the CRISPR/Cas system. Genesis 51, 827–834 (2013).

Aluru, N. et al. Targeted mutagenesis of aryl hydrocarbon receptor 2a and 2b genes in Atlantic killifish (Fundulus heteroclitus). Aquat. Toxicol. 158, 192–201 (2015).

Momose, T. & Concordet, J.-P. Diving into marine genomics with CRISPR/Cas9 systems. Mar Genomics 30, 55–65 (2016).

Reardon, S. Welcome to the CRISPR zoo. Nature 531, 160–163 (2016).

Bae, S., Kweon, J., Kim, H. S. & Kim, J.-S. Microhomology-based choice of Cas9 nuclease target sites. Nat. Methods 11, 705–706 (2014).

Chuai, G. et al. Deciphering relationship between microhomology and in-frame mutation occurrence in human CRISPR-based gene knockout. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids 5, e323 (2016).

Aslan, Y., Tadjuidje, E., Zorn, A. M. & Cha, S.-W. High efficiency non-mosaic CRISPR mediated knock-in and mutations in F0 Xenopus. Development 144, dev.152967–2858 (2017).

Houliston, E., Momose, T. & Manuel, M. Clytia hemisphaerica: a jellyfish cousin joins the laboratory. Trends Genet 26, 159–167 (2010).

Leclère, L., Copley, R. R., Momose, T. & Houliston, E. Hydrozoan insights in animal development and evolution. Curr Opin Genet Dev 39, 157–167 (2016).

Shimomura, O., Johnson, F. H. & Saiga, Y. Extraction, purification and properties of aequorin, a bioluminescent protein from the luminous hydromedusan, Aequorea. J Cell Comp Physiol 59, 223–239 (1962).

Fourrage, C., Swann, K., Gonzalez Garcia, J. R., Campbell, A. K. & Houliston, E. An endogenous green fluorescent protein-photoprotein pair in Clytia hemisphaerica eggs shows co-targeting to mitochondria and efficient bioluminescence energy transfer. Open Biol 4, 130206–130206 (2014).

Choksi, S. P., Lauter, G., Swoboda, P. & Roy, S. Switching on cilia: transcriptional networks regulating ciliogenesis. Development 141, 1427–1441 (2014).

Bisgrove, B. W., Makova, S., Yost, H. J. & Brueckner, M. RFX2 is essential in the ciliated organ of asymmetry and an RFX2 transgene identifies a population of ciliated cells sufficient for fluid flow. Dev Biol 363, 166–178 (2012).

Chung, M.-I. et al. RFX2 is broadly required for ciliogenesis during vertebrate development. Dev Biol 363, 155–165 (2012).

Bonnafe, E. et al. The transcription factor RFX3 directs nodal cilium development and left-right asymmetry specification. Mol Cell Biol 24, 4417–4427 (2004).

Swoboda, P., Adler, H. T. & Thomas, J. H. The RFX-type transcription factor DAF-19 regulates sensory neuron cilium formation in C. elegans. Mol Cell 5, 411–421 (2000).

Momose, T., Kraus, Y. & Houliston, E. A conserved function for Strabismus in establishing planar cell polarity in the ciliated ectoderm during cnidarian larval development. Development 139, 4374–4382 (2012).

McVey, M. & Lee, S. E. MMEJ repair of double-strand breaks (director’s cut): deleted sequences and alternative endings. Trends Genet 24, 529–538 (2008).

van Overbeek, M. et al. DNA Repair Profiling Reveals Nonrandom Outcomes at Cas9-Mediated Breaks. Mol Cell 63, 633–646 (2016).

Brinkman, E. K., Chen, T., Amendola, M. & van Steensel, B. Easy quantitative assessment of genome editing by sequence trace decomposition. Nucleic Acids Res 42, e168–e168 (2014).

Quiroga Artigas, G. et al. A gonad-expressed opsin mediates light-induced spawning in the jellyfish Clytia. Elife 7, 81 (2018).

Thyme, S. B. & Schier, A. F. Polq-Mediated End Joining Is Essential for Surviving DNA Double-Strand Breaks during Early Zebrafish Development. Cell Rep 15, 707–714 (2016).

Tesson, L. et al. Knockout rats generated by embryo microinjection of TALENs. Nat. Biotechnol. 29, 695–696 (2011).

Denoeud, F. et al. Plasticity of animal genome architecture unmasked by rapid evolution of a pelagic tunicate. Science 330, 1381–1385 (2010).

Sakuma, T., Nakade, S., Sakane, Y., Suzuki, K.-I. T. & Yamamoto, T. MMEJ-assisted gene knock-in using TALENs and CRISPR-Cas9 with the PITCh systems. Nat Protoc 11, 118–133 (2016).

Aida, T. et al. Gene cassette knock-in in mammalian cells and zygotes by enhanced MMEJ. BMC Genomics 17, 979 (2016).

Nakade, S. et al. Microhomology-mediated end-joining-dependent integration of donor DNA in cells and animals using TALENs and CRISPR/Cas9. Nat Commun 5, 5560 (2014).

Zimmermann, M. & de Lange, T. 53BP1: pro choice in DNA repair. Trends Cell Biol 24, 108–117 (2014).

Escribano-Díaz, C. et al. A cell cycle-dependent regulatory circuit composed of 53BP1-RIF1 and BRCA1-CtIP controls DNA repair pathway choice. Mol Cell 49, 872–883 (2013).

Guirouilh-Barbat, J. et al. 53BP1 Protects against CtIP-Dependent Capture of Ectopic Chromosomal Sequences at the Junction of Distant Double-Strand Breaks. PLoS Genet 12, e1006230 (2016).

Yun, M. H. & Hiom, K. CtIP-BRCA1 modulates the choice of DNA double-strand-break repair pathway throughout the cell cycle. Nature 459, 460–463 (2009).

Symington, L. S. & Gautier, J. Double-strand break end resection and repair pathway choice. Annu Rev Genet 45, 247–271 (2011).

Taleei, R. & Nikjoo, H. Biochemical DSB-repair model for mammalian cells in G1 and early S phases of the cell cycle. Mutat. Res. 756, 206–212 (2013).

David, C. N. Interstitial stem cells in Hydra: multipotency and decision-making. Int J Dev Biol 56, 489–497 (2012).

Plickert, G., Frank, U. & Müller, W. A. Hydractinia, a pioneering model for stem cell biology and reprogramming somatic cells to pluripotency. Int J Dev Biol 56, 519–534 (2012).

Leclère, L. et al. Maternally localized germ plasm mRNAs and germ cell/stem cell formation in the cnidarian Clytia. Dev Biol 364, 236–248 (2012).

Haddock, S. H. D., Moline, M. A. & Case, J. F. Bioluminescence in the sea. Ann Rev Mar Sci 2, 443–493 (2010).

Widder, E. A. Bioluminescence in the ocean: origins of biological, chemical, and ecological diversity. Science 328, 704–708 (2010).

Salih, A., Larkum, A., Cox, G., Kühl, M. & Hoegh-Guldberg, O. Fluorescent pigments in corals are photoprotective. Nature 408, 850–853 (2000).

Kistler, W. S., Horvath, G. C., Dasgupta, A. & Kistler, M. K. Differential expression of Rfx1-4 during mouse spermatogenesis. Gene Expr Patterns 9, 515–519 (2009).

Wu, Y. et al. Transcription Factor RFX2 Is a Key Regulator of Mouse Spermiogenesis. Sci Rep 6, 20435 (2016).

Ménoret, S. et al. Homology-directed repair in rodent zygotes using Cas9 and TALEN engineered proteins. Sci Rep 5, 14410 (2015).

Carré, D. & Carré, C. Origin of germ cells, sex determination, and sex inversion in medusae of the genus Clytia (Hydrozoa, leptomedusae): the influence of temperature. J. Exp. Zool. 287, 233–242 (2000).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the members of the Momose team for support, animal maintenance, and fruitful discussions, and Loann Gissat, Sophie Collet and Laurent Gilletta for animal care. TEFOR infrastructures for encouraging this collaboration. We would like to thank Evelyn Houliston, Christine Vesque and Brandon Weissbourd for critical reading of manuscript. This work was supported by TEFOR (http://tefor.net/pages/main/), Agence National de la Recherche (ANR-11-IDEX-0004-02, Sorbonne Universités). A.D., C.G. and J.-P.C. were supported by ANR Investissement d’Avenir ANR-II-INSB-0014. The work of K.S. and K.I. was partly supported by Grants-in-Aid from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan to K.I. (no. 15K14566). Animal culture and maintenance was supported by EMBRC-Fr and by CNRS core support to the LBDV.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.M. organized and performed experiments. T.M., C.G. and J.P.C. analysed data. A.D.C. made 3xNLS-Cas9 protein. K.I. and K.S. analysed flagella motility defect in CheRfx123 mutant.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Momose, T., De Cian, A., Shiba, K. et al. High doses of CRISPR/Cas9 ribonucleoprotein efficiently induce gene knockout with low mosaicism in the hydrozoan Clytia hemisphaerica through microhomology-mediated deletion. Sci Rep 8, 11734 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-30188-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-30188-0

This article is cited by

-

Epithelial wound healing in Clytia hemisphaerica provides insights into extracellular ATP signaling mechanisms and P2XR evolution

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

siRNA-mediated gene knockdown via electroporation in hydrozoan jellyfish embryos

Scientific Reports (2022)

-

The PI3K subunits, P110α and P110β are potential targets for overcoming P-gp and BCRP-mediated MDR in cancer

Molecular Cancer (2020)

-

Cnidofest 2018: the future is bright for cnidarian research

EvoDevo (2019)

-

The genome of the jellyfish Clytia hemisphaerica and the evolution of the cnidarian life-cycle

Nature Ecology & Evolution (2019)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.