Abstract

An effective resistivity relevant to collisionless magnetic reconnection (MR) in plasma is presented. It is based on the argument that pitch angle scattering of electrons in the small electron diffusion region around the X line can lead to an effective, resistivity in collisionless plasma. The effective resistivity so obtained is in the form of a power law of the local plasma and magnetic field parameters. Its validity is confirmed by direct collisionless particle-in-cell (PIC) simulation. The result agrees very well with the resistivity (obtained from available data) of a large number of environments susceptible to MR: from the intergalactic and interstellar to solar and terrestrial to laboratory fusion plasmas. The scaling law can readily be incorporated into existing collisional magnetohydrodynamic simulation codes to investigate collisionless MR, as well as serve as a guide to ab initio theoretical investigations of the collisionless MR process.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Magnetic reconnection (MR) often occurs in plasmas containing sheared magnetic fields and can efficiently convert magnetic energy into the kinetic and thermal energies of the charged particles1,2,3. The process plays important roles in the evolution of the solar corona4,5, the geomagnetic tail6,7, the magnetosphere8,9, the intergalactic and interstellar, as well as laboratory plasmas10,11. In particular, collisionless or fast MR (FMR) on time scales much less than the inter-particle collision time can occur. FMR has often been attributed to anomalous resistivity arising from local current-instability driven turbulence in the small electron diffusion region of the MR12,13. However, the evolution and effect of the turbulence during the MR are difficult to follow and remain unclear. Existing studies14,15 have noted that the lifetime of a particle in the diffusion region can be considered as an effective collision time, since in terms of its momentum and energy changes, the electron dynamics in the electron diffusion region resembles that of electrons being scattered by collisions, except that here the scattering partners are the local magnetic and electric fields. In particular, Speiser14 introduced an ad hoc resistivity (more precisely, conductivity) based on the behavior of the electric current flow in the diffusion region. However, the problem remains unclear and no general conclusion can be drawn14,15,16.

It is well known that pitch-angle scattering of electrons in highly bending magnetic fields such as that in the diffusion region around the X point of MR can lead to particle momentum transfer from the parallel to the perpendicular initial current direction. In this paper, we reconsider the dynamics of electrons in this small region. The transit times of typical electrons in the region near the X line are determined by following their motion as the FMR process evolves. An effective resistivity in the form of power-law scaling of the most relevant local plasma parameters is obtained by replacing the mean-free-time in the expression for the collisional resistivity by an ensemble averaged electron transit time that depends on the local plasma and field parameters in the diffusion region. Validity of our approach is confirmed by full particle-in-cell (PIC) simulation of the FMR. Moreover, when compared with a large number of plasmas susceptible to MR: from the intergalactic and interstellar space to solar and terrestrial, as well as fusion, plasmas, it is found that the effective resistivity agrees very well with that estimated from the known parameters of these plasmas. The scaling law can readily be incorporated into the existing macroscopic MHD simulation codes17 for investigating FMR in complex space and fusion plasmas, as well as serve as guide for detailed theoretical investigation of the FMR physics.

Analytical formulation of effective resistivity

Accordingly, collisionless MR can be investigated by replacing the mean free time τmft between collisions in the collisional resistivity ηcoll = me/ne2τmft, where n, e, and me are the electron number density, charge, and mass, respectively, by the mean transit time \({\bar{\tau }}_{transit}\) of electrons in the diffusion region around the X line (see Fig. 1). The resulting effective, or collisionless, resistivity \({\eta }_{eff}={m}_{e}/n{e}^{2}{\bar{\tau }}_{transit}\) can then be implemented in the existing theories and MHD simulation codes. In the following, we shall obtain \({\bar{\tau }}_{transit}\) by concentrating only on, in our opinion, the most relevant physics involved.

The local magnetic field \({\boldsymbol{B}}={{B}}_{x}z\hat{{\boldsymbol{x}}}/{L}_{z}+{{B}}_{z}x\hat{{\boldsymbol{z}}}/{L}_{x}\) and induction electric field \({\boldsymbol{E}}={{E}}_{y}\hat{y}\) in the diffusion region. The current sheet is in the y direction. The magnetic field increases (from null) with the distance from the X line, which is in the y direction and appears in the x, z plane here as the X point at (0, 0). Several idealized electron trajectories are shown as dashed curves.

The local magnetic and electric fields in the electron diffusion region of the MR (Fig. 1) can be approximated by

where Lx and Lz are the characteristic lengths of the electron diffusion region, respectively, and the coefficients Bx, Bz(<<Bx), and Ey are constants. When Lz << Lx, the current sheet becomes elongated. This MR geometry is ofter referred to as of Y type.

The electron trajectory near the X line is then governed by

where for simplicity we shall assume (consistent with the PIC simulation results below) that the electron velocity vy in the current sheet varies only a little from the average value 〈vy〉 ~ −Jy/ne.

where \({\tau }_{x}=\sqrt{|{m}_{e}{L}_{x}/e{v}_{y}{B}_{z}|}\) and \({\tau }_{z}=\sqrt{|{m}_{e}{L}_{z}/e{v}_{y}{B}_{x}|}(\ll {\tau }_{x})\), and (x0, z0) and (vx0, vz0) are the initial position and velocity of the electron.

Equations (5) and (6) show that the electron is accelerated in the x direction but it only oscillates in the z direction. We can thus consider the transit time τtransit as the time for the electron to traverse the diffusion region in the x direction. Accordingly, from equation (5) we get

where Dx = x(τtransit) can be chosen to be at the edge of the simulation box.

Near the X line, we can also reasonably assume that thermal effects can be neglected and the initial in-plane electron velocity is nearly zero. Considering that the electron motion in the z direction is oscillatory, for the transit time we only need to follow its motion in the x direction. Accordingly, equation (7) becomes

Since the initial position x0 of an electron can be anywhere inside the diffusion region, the mean transit time is

the result of \({\bar{\tau }}_{transit}\) is independent of Dx. So that the effective collisionless resistivity is

In deriving the electron transit time, we have made the reasonable but unsubstantiated assumption on the existence of a collisionless, or effective, resistivity that imitates the function of the classical collisional resistivity in the fluid description of the plasma. For verification, we next carry out full PIC simulations of the FMR in collisionless plasma.

Particle-in-Cell simulation

We have performed 2.5D full PIC simulations for plasma particle motion in the diffusion region by assuming ∂y = 0. For simplicity, we use the charge-conservation scheme (CCS) instead of solving the Poisson equation, and the finite difference time domain (FDTD) method to solve the other Maxwell’s equations. The equations used in the PIC simulations are

where c is the light speed, vj and pj = mjvj are the particle velocity and momentum, respectively. The variables are normalized as follows: x/di0→x, (Vj, vj)/vAi0→(Vj, vj), ωci0t→t, B/B0→B, E/E0→E, J/J0→J, n/n0→n, pj/mivAi0→pj, where \({d}_{i0}=c/{\omega }_{pi0}=c/\sqrt{{n}_{0}{e}^{2}/{\mu }_{0}{m}_{i}}\), \({v}_{Ai0}={B}_{0}/\sqrt{{\mu }_{0}{n}_{i0}{m}_{i}}\), ωci0 = eB0/mi, E0 = vAi0B0, and J0 = n0evAi0.

For the PIC simulations, we set \({v}_{Ai0}/c=0.05\), the ion-to-electron mass ratio μ = mi/me is from 25 to 400, and the initial ion-to-electron temperature ratio is Ti/Te = 5. Our simulation domain is −Dx/2≤ x ≤Dx/2, −Dz/2 ≤ z ≤Dz/2, where Dx = 12.8di0, Dz = 6.4di0, dx = dz = 0.01di0 and the time step is ωci0Δt = 0.0002. Periodic and closed boundary conditions are adopted in the x and z directions, respectively. Nearly 82 million simulation particles for each species are used.

We use the Harris equilibrium as the initial configuration. The initial magnetic field is given by

and the initial density profile is

where B0 = 1.0, b0 = 0.5, n0 = 1.0, nb = 0.2, and b0 is the width of the current sheet with the current intensity given by

In the simulation, the reconnection process is initiated by a small perturbation of the magnetic field.

Pressure balance yields

where P and B are the local thermal pressure and magnetic field, β = P/(B2/2), and P is normalized by \({B}_{0}^{2}/2{\mu }_{0}\). Here we set β = 0.2.

Comparison of the analytical and simulated resistivities

We first examine the y component of the velocity vy of electrons entering and leaving the electron diffusion region. For ion-to-electron mass ratio μ = 400, during the peak reconnection period (from t = 16 to 17) we found that the average change of vy is less than 10%. That is, vy is indeed roughly constant, as assumed in the evaluation of (5) and (6).

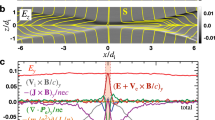

Next we compare the resistivities from our analytical model and the PIC simulation. Figure 2 shows the evolution of the resistivities in the electron diffusion region. In the analytical formula for ηeff, the electron number density n, velocity vy, Bz, and Lx have been replaced by, as calculated from the PIC simulation results, the average electron number density \(\bar{n}\) and electron velocity \({\bar{v}}_{y}\) in the electron diffusion region (of size of de), the maximum Bz, and the characteristic length Lx of Bz in the X-point region, respectively. On the other hand, the resistivity from the PIC simulation is calculated directly from the relation ηs = Ey/Jy by substituting the measured values of the average electric field intensity \({\bar{E}}_{y}\) and sheet-current density \(\bar{J}\). We see that our effective resistivity agrees quite well with the collisionless resistivity obtained from the PIC simulations. In particular, in the fast reconnection phase both resistivities increase rapidly and in a similar manner, thereby verifying the scaling of the field parameters in our model effective resistivity. We can also see that the peak value of the resistivity decreases with increase of the mass ratio μ, and the analytical and simulation results approach each other.

Evolution of the effective resistivity ηeff (blue curve with stars) and the collisionless resistivity ηs (red curve with circles) obtained from the PIC simulations. The panels a to d are for μ = 25, 100, 256, and 400, respectively. Note that the quantitative discrepancy decreases as the the mass ratio becomes more and more realistic.

Discussion and Summary

In collisional plasma, the characteristic thickness of the current sheet taking into account magnetic field diffusion is18,19 \({{\rm{\Delta }}}_{SP}=\sqrt{{\eta }_{spz}L/{\mu }_{0}{v}_{A}}\), where L is the plasma size, vA is the Alfven speed, and ηspz is the Spitzer resistivity (based on Coulomb collisions). For the parameters of the Earth’s magnetopause and magnetotail20, the half-thickness of the thinnest current sheet during the nonlinear stage of magnetic reconnection can be of the order 10 m that is four to five orders of magnitude smaller than that obtained from the satellite data during magnetic reconnection: namely, ~100 km in the magnetopause21,22 and ~1000 km in the magnetotail23,24. Such a huge descrepancy suggests that Coulomb collisions are not the dominant dissipation mechanism for MR in the magnetopause and magnetail.

The effective resistivity in our model can be rewritten in the form of a power law:

where we have used the relations \(ne{v}_{y}={\mu }_{0}^{-1}{\partial }_{z}{B}_{x}\)\( \sim {\mu }_{0}^{-1}{B}_{0}/{L}_{z}\), as well as the relation \({\partial }_{x}{B}_{z} \sim \alpha {\partial }_{z}{B}_{x}\) between the local magnetic field components near the X line. The parameter α is thus the ratio of the characteristic lengths of Bx and Bz. Simulations have shown that in the MR configuration α increases as reconnected magnetic field Bz increases with time in the diffusion region and α is of order 0.1 when MR gets into the nonlinear stage. In the magnetotail20 on Earth’s nightside, the electron density is ne(ni) ≈ 0.3cm−3, the electron temperature is Te ≈ 600eV, the magnetic field is B0 ≈ 2 × 10−8T, and plasma size L ≈ 100RE, the current sheet thickness is about ΔSP ≈ 0.15RE ≈ 953km in the nonlinear phase of magnetic reconection with α = 0.1. On the other hand, for the magnetopause20 on the Earth’s dayside, with electron density ne(ni) ≈ 10cm−3, electron temperature Te ≈ 300eV, magnetic field B0≈5 × 10−8T, and plasmas size L ≈ 10RE, the current sheet thickness is ΔSP ≈ 0.021RE ≈ 137km. Thus, for both the magnetopause and magnetotail, the current sheet thicknesses as predicted by our model are in good agreement with that from the satellite observations. Moreover, one can easily show that for the parameters of the experimental device MRX20, our model yields ΔSP ≈ 3.38 cm, which is in good agreement with that from the direct laboratory measurement.

It is of interest to make a broader comparison of the results from our model with that from existing data on space and laboratory plasmas where MR is observed or expected to exist. Since classical collisions can be important or relevant in some of the environments20, it is useful to introduce the total resistivity ηtot=ηspz+ηeff. Figure 3 shows the plot of ηtot normalized by the Spitzer resistivity ηspz versus the mean-free-path λmfp normalized by the Sweet-Parker current sheet thickness ΔSP = 2Lz. From Fig. 3, it is clearly shown that all data points are distributed near the best-fitting line. Since \({\eta }_{spz}={m}_{e}{v}_{the}/n{e}^{2}{\tau }_{mft}{v}_{the}={m}_{e}\sqrt{3k{T}_{e}/{m}_{e}}/n{e}^{2}{\lambda }_{mfp}\), we have the power-law scaling ηeff/ηspz = [4π−1α0.5(3μ0kTene)−0.5B0]λmfp/ΔSP = Cλmfp/ΔSP, should correspond to the slope of the data points in the figure. For α = 0.1 in the nonlinear stage of magnetic reconnection, we find that C is in the range 3 × 10−3 to 4 for collisionless (λmfp/ΔSP > 1) plasmas. The slope of the best-fit (red dashed) line in Fig. 3 is C = 0.1, which is in the middle of its range. We note that the data points only slightly deviate from the best-fit line, and can be attributed to uncertainties in the obervational data. The somewhat larger deviation for the data points from the magnetic-confinement-fusion devices ITER and TFTR can be attributed to the strong guiding magnetic field. It is well known that a guide field can suppress magnetic reconnection or reduce the effective resistivity, which is consistent with the fact that the ITER and TFTR data points are located below the best-fit line. The results here suggest that pitch angle scattering of electrons due to bending magnetic field lines, which is the basic assumption of our model, may be responsible for fast MR in collisionless plasmas.

Plot of the normalized total resistivity ηtot/ηspz for space and laboratory plasmas exhibiting MR versus the normalized mean-free-path λmfp/ΔSP. Here, the thickness of the current sheet according to the Sweet-Parker model is \({{\rm{\Delta }}}_{SP}=2{L}_{z} \sim 2L/{S}_{L}^{1/2},\) where SL = μ0LvA/ηtot is the Lundquist number, or the ratio of the resistive to Alfvèn times, and L is the overall plasma size. Note that the normalization parameters ηspz and ΔSP are different for different data points. The solid circles and triangles are for collisional (λmfp/ΔSP <1) and collisionless (λmfp/ΔSP >1) plasmas, respectively. The corresponding current sheet thicknesses ΔSP based on our effective resistivity are given in the insets. The red dashed line is the best fit for the data points in the collisionless plasma regime (λmfp/ΔSP > 1).

The effective resistivity in our 2D model is mainly a result of diversion of electrons in the electron diffusion region, which has very small spatial scale. Three-dimensional (3D) effects are ignorable if the spatial scale of the magnetic field in the third direction is larger than the electron inertia length. This condition is usually valid for space and laboratory plasmas, which explains why the effective resistivity from our model agrees very well with that of a large number of environments, namely from intergalactic and interstellar to solar and terrestrial to laboratory fusion plasmas. The reconnection rate in general depends on the ratio between the thickness and length of the diffusion region, or the current sheet. The thickness is usually determined by dissipation, or resistivity, of the system. Therefore, for given resistivity, the reconnection rate can increase with decrease of the current sheet length, say by an external driving force. For example, in tokamak plasmas, the slower tearing modes correspond to spontaneous MR and the sawtooth oscillations correspond to FMR driven by internal kink instabilities.

In summary, for understanding FMR we have introduced an effective resistivity that contains no free parameters. The effective resistivity is based on self-consistent scattering or acceleration of electrons by bending of magnetic field lines, and it agrees in magnitude with that of a large number of environments where MR is observed or suspected. It can also be readily adapted in existing collisional-fluid simulation codes for investigating collisionless FMR. The present work can also serve as a guide for a formal first-principles derivation of such an effective resistivity. Finally, it may be of interest to point out that our results are clearly also applicable to very small scale and very fast MR in the absence of ion dynamics. In fact, such novel ultrafast (45 millisecond) MR phenomena have been recently reported to be occuring within the entangled magnetic fields in the Earth’s turbulent magnetosheath.25

References

Dungey, J. W. Interplanetary magnetic field and the auroral zones. Physical Review Letters 6, 47 (1961).

Yamada, M., Kulsrud, R. & Ji, H. Magnetic reconnection. Reviews of Modern Physics 82, 603–664, https://doi.org/10.1103/RevModPhys.82.603 (2010).

Yamada, M. et al. Conversion of magnetic energy in the magnetic reconnection layer of a laboratory plasma. Nature communications 5, 4774 (2014).

Kopp, R. & Pneuman, G. Magnetic reconnection in the corona and the loop prominence phenomenon. Solar Physics 50, 85–98 (1976).

Wyper, P. F., Antiochos, S. K. & DeVore, C. R. A universal model for solar eruptions. Nature 544, 452–455 (2017).

Øieroset, M., Phan, T., Fujimoto, M., Lin, R. & Lepping, R. In situ detection of collisionless reconnection in the Earth’s magnetotail. Nature 412, 414–417 (2001).

Artemyev, A., Angelopoulos, V. & Runov, A. On the radial force balance in the quiet time magnetotail current sheet. Journal of Geophysical Research: Space Physics 121, 4017–4026 (2016).

Phan, T. D., Lin, R. P., Fuselier, S. A. & Fujimoto, M. Wind observations of mixed magnetosheath‐plasma sheet ions deep inside the magnetosphere. Journal of Geophysical Research: Space Physics 105, 5497–5505 (2000).

Burch, J. et al. Electron-scale measurements of magnetic reconnection in space. Science 352, aaf2939 (2016).

Lu, S. et al. Formation of super-Alfvénic electron jets during laser-driven magnetic reconnection at the Shenguang-II facility: particle-in-cell simulations. New Journal of Physics 16, 083021 (2014).

Wang, S. & Ma, Z. Influence of toroidal rotation on resistive tearing modes in tokamaks. Phys. Plasmas 22, 122504 (2015).

Malyshkin, L. M., Linde, T. & Kulsrud, R. M. Magnetic reconnection with anomalous resistivity in two-and-a-half dimensions. I. Quasistationary case. Phys. Plasmas 12, 102902 (2005).

Eyink, G. et al. Flux-freezing breakdown in high-conductivity magnetohydrodynamic turbulence. Nature 497, 466–469 (2013).

Speiser, T. Conductivity without collisions or noise. Planetary and Space Science 18, 613–622 (1970).

Divin, A. et al. Scaling of the inner electron diffusion region in collisionless magnetic reconnection. Journal of Geophysical Research: Space Physics 117 (2012).

Baum, P. & Bratenahl, A. Conduction mode variation and intertial conductivity. Astrophysics and Space Science 49, 473–480 (1977).

Ma, Z. W. & Bhattacharjee, A. Hall magnetohydrodynamic reconnection: The Geospace Environment Modeling challenge. Journal of Geophysical Research-Space Physics 106, 3773–3782, https://doi.org/10.1029/1999ja001004 (2001).

Sweet, P. A. The neutral point theory of solar flares, in Electromagnetic Phenomena in Cosmical Physics, edited by B. Lehnert (Cambridge University Press, 1958), p. 123.

Parker, E. N. Sweet’s mechanism for merging magnetic fields in conducting fluids. Journal of Geophysical Research 62, 509–520 (1957).

Ji, H. & Daughton, W. Phase diagram for magnetic reconnection in heliophysical, astrophysical, and laboratory plasmas. Phys. Plasmas 18, 111207 (2011).

Le, G. & Russell, C. The thickness and structure of high beta magnetopause current layer. Geophysical research letters 21, 2451–2454 (1994).

Panov, E. et al. CLUSTER spacecraft observation of a thin current sheet at the Earth’s magnetopause. Advances in Space Research 37, 1363–1372 (2006).

Pulkkinen, T. et al. Thin current sheets in the magnetotail during substorms: CDAW 6 revisited. Journal of Geophysical Research: Space Physics 99, 5793–5803 (1994).

Sergeev, V., Angelopoulos, V., Carlson, C. & Sutcliffe, P. Current sheet measurements within a flapping plasma sheet. Journal of Geophysical Research: Space Physics 103, 9177–9187 (1998).

Phan, T. D. et al. Electron magnetic reconnection without ion coupling in Earth's turbulent magnetosheath. Nature 557, 201 (2018).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank L. C. Lee and L. Chen for their useful suggestions. This work is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant No. 41474123 and 11775188, the Special Project on High-performance Computing under the National Key R&D Program of China No. 2016YFB0200603, Fundamental Research Fund for Chinese Central Universities. The simulation data is available upon request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.C. and H.W.Z. coordinated the study and performed the numerical simulations, Z.W.M. provided the idea and analyzed the data. Z.W.M., M.Y.Y. and T.C. wrote the paper. All the authors participated in the discussion.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ma, Z.W., Chen, T., Zhang, H.W. et al. Effective Resistivity in Collisionless Magnetic Reconnection. Sci Rep 8, 10521 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-28851-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-28851-7

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.