Abstract

The Devonian period ended with one of the largest mass extinctions in the Earth history. It comprised a series of separate events, which eliminated many marine species and led to long-term post-extinction reduction in body size in some groups. Surprisingly, crinoids were largely unaffected by these extinction events in terms of diversity. To date, however, no study examined the long-term body-size trends of crinoids over this crucial time interval. Here we compiled the first comprehensive data sets of sizes of calyces for 262 crinoid genera from the Frasnian-Visean. We found that crinoids have not experienced long-term reduction in body size after the so-called Hangenberg event. Instead, size distributions of calyces show temporal heterogeneity in the variance, with an increase in both the mean and maximum biovolumes between the Famennian and Tournaisian. The minimum biovolume, in turn, has remained constant over the study interval. Thus, the observed pattern seems to fit a Brownian motion-like diffusion model. Intriguingly, the same model has been recently invoked to explain morphologic diversification within the eucladid subclade during the Devonian-early Carboniferous. We suggest that the complex interplay between abiotic and biotic factors (i.e., expansion of carbonate ramps and increased primary productivity, in conjunction with predatory release after extinction of Devonian-style durophagous fishes) might have been involved not only in the early Mississippian diversity peak of crinoids, but possibly also in their overall passive expansion into larger body-size niches.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Body size is a key biological property of organisms, which has a significant influence on life functions, generation time, population and home range sizes1. Numerous works reporting the changes in body size of different groups at different length scales have been published2,3,4,5. Recent global-data studies suggest that animals generally increased their sizes over Phanerozoic4. An increase in body size over evolutionary time, a pattern commonly referred to as “Cope-Depéret” rule, is thought to confer many advantages upon organisms, but also induces costs and problems6. Indeed, counter-examples documenting reduction of body sizes are also known7,8,9,10,11. Notably, one of the most intriguing evolutionary phenomenon is the Lilliput effect11, which refers to a decrease in body size of fauna associated with the aftermath of extinctions. In general, four models were invoked to explain this effect: extinction of large taxa, post-crisis appearance of many small taxa, temporary disappearance of large taxa and within-lineage size decrease8.

The Late Devonian extinction is typically considered to be one of the Big Five mass extinctions. However, this extinction was not geologically instantaneous, in that it is characterized by a series of extinction pulses associated with anoxic events12,13,14. Furthermore, as stressed by Stigall15 diversity decline throughout the Late Devonian was mostly caused by a reduction in origination rates rather than elevated extinction. At around the Frasnian/Famennian boundary, commonly referred to as the lower and upper Kellwasser events, many reef-building organisms, such as stromatoporoid sponges and tabulate corals, suffered severely12. Notably, stromatoporoid sponges became totally extinct at around the Famennian/Tournaisian boundary. This boundary corresponds to the so-called Hangenberg event marking the last spike in the Devonian extinctions. Many other benthic organisms also became extinct at this time14. The Hangenberg event, however, was the most severe for jawed vertebrate clades, eliminating more than 96% of species, and also leading to post-extinction global shrinkage in vertebrate size16.

Despite significant decline in the overall biodiversity during the Late Devonian extinctions, crinoids were one of the few invertebrate groups that were not substantially affected during this time. Noteworthy, an increase in the total number of crinoid genera, leading to the major ecological reorganization (transition from the so-called Middle Paleozoic to the Late Paleozoic Crinoid Evolutionary Fauna), occurred in the early Visean17,18,19,20. Indeed, recent study demonstrated that origination rates of crinoids exceeded extinction rates at around Devonian/Carboniferous boundary18. Notably, crinoids reached their Phanerozoic peak of generic richness and abundance in the early Mississippian, which has been referred to as the ‘Age of Crinoids’19,20. Yet, no studies investigated whether crinoids changed their sizes during this crucial interval. To test this we thus assembled a database comprising sizes of calyces for 262 crinoid genera occurring in the Frasnian-Visean.

Results

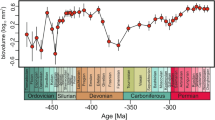

Our database shows that the median and mean size of crinoid calyces increased during the Frasnian-Visean interval (Fig. 1; Table 1). Notwithstanding the method used (details in Supplementary Materials), Frasnian and Famennian medians of log-transformed biovolumes are statistically indistinguishable from each other [Mann-Whitney U test; Frasnian versus Famennian: P = 1 (range through approach) or P = 1 (per-occurrence approach); details in Supplementary Tables S1–S4, S17]. By contrast, means and medians of Tournaisian and Visean sizes are much higher (Table 1; details in Supplementary Tables S2, S4, S17). The magnitude of size increase between Devonian and Carboniferous stages (Visean, in particular) is statistically significant (Table 1). The crinoid class-level trend of increasing size throughout the investigated interval is supported by linear regressions [ordinary least squares (OLS) and reduced major axis (RMA) P < 0.05; details in Supplementary Figs S12–S15; Tables S18–S21]. The resulting class-level size distributions (Fig. 1) using both approaches are similar and clearly show temporal heterogeneity in the variance, with an increase in the variance between the Famennian and Tournaisian. Interestingly, once the lower limit of size is reached (Frasnian or Famennian, depending on the method used), it remained constant over the study interval. Similar trends can be observed at the subclass-level, with two major sister clades (Camerata and Pentacrinoidea) displaying higher median and mean body sizes in the Carboniferous (Visean, in particular) (Table 1, Fig. 2; Supplementary Tables S5–S8, S17). However, the differences between median sizes in stages are only statistically significant for the most diverse clade – Pentacrinoidea (Fig. 2B; Table 1; Supplementary Tables S7, S8, S17). Likewise, a trend of increasing size throughout the study interval is statistically significant for Pentacrinoidea only [ordinary least squares (OLS) and reduced major axis (RMA) P < 0.05; see Supplementary Figs S16–S19; Tables S22–S25]. It should be noted, however, that although trends of increasing size of Camerata throughout Frasnian-Visean interval lack statistical significance (presumably due to lower number of data points), r values remain positive (Supplementary Figs S16–S17, Tables S22, S23). In contrast to Pentacrinoidea, for which minimum and maximum biovolumes remained stable over the study interval, the variance of Camerata reveals strong temporal heterogeneity (Fig. 2A).

Box plots showing distribution of calyx volumes of holotypes of type species for the uppermost Devonian and lowermost Carboniferous using two different methods: “range through approach” (A), and “per-occurrence approach” (B); the 25–75 percent quartiles are drawn using a box, the median is shown with a horizontal line inside the box, the minimal and maximal values are shown with short horizontal lines (“whiskers”). Fras – Frasnian; Famen – Famennian; Tourn – Tournaisian.

Box plots showing distribution of calyx volumes of holotypes of type species for the uppermost Devonian and lowermost Carboniferous using “range through approach” for the two sister clades Camerata (A) and Pentacrinoidea (B); the 25–75 percent quartiles are drawn using a box, the median is shown with a horizontal line inside the box, the minimal and maximal values are shown with short horizontal lines (“whiskers”). Fras – Frasnian; Famen – Famennian; Tourn – Tournaisian.

At the parvclass level (Cladida vs. Disparida) there are some notable differences in the body-size trends (Fig. 3; Supplementary Figs S20–S23; Tables S9–S12, S17, S26–29). Although size distributions of cladids are similar to those observed at higher taxonomic levels (Fig. 3A), disparids show lower median body sizes in the Carboniferous than in the Devonian stages (Fig. 3B) (note, however, that their mean sizes actually increase, see Table 1). Interestingly, their maximum and minimum biovolumes increased over the study interval. However, body-size trends of disparids, which are a low-diversity goup (only represented by several genera in the study interval), should be treated with caution. Given such scanty data, firm statistical conclusions cannot be obtained (Table 1, Supplementary Table 17). At lower taxonomic level (superorder-magnorders: Flexibilia vs. Eucladida), the patterns of size distribution are very similar to each other (Supplementary Figs S24–S27; Tables S13–S17, S30–S33), and are comparable to those seen at higher taxonomic levels (Fig. 4).

Box plots showing distribution of calyx volumes of holotypes of type species for the uppermost Devonian and lowermost Carboniferous using “range through approach” for the two sister clades Cladida (A) and Disparida (B); the 25–75 percent quartiles are drawn using a box, the median is shown with a horizontal line inside the box, the minimal and maximal values are shown with short horizontal lines (“whiskers”). Fras – Frasnian; Famen – Famennian; Tourn – Tournaisian.

Box plots showing distribution of calyx volumes of holotypes of type species for the uppermost Devonian and lowermost Carboniferous using “range through approach” for the two sister clades Flexibilia (A) and Eucladida (B); the 25–75 percent quartiles are drawn using a box, the median is shown with a horizontal line inside the box, the minimal and maximal values are shown with short horizontal lines (“whiskers”). Fras – Frasnian; Famen – Famennian; Tourn – Tournaisian.

Discussion

It has been argued that large organisms are more vulnerable to environmental stress and extinction6. Not surprisingly, size reduction occurred in the aftermath of major Phanerozoic extinctions8, and has been documented in a variety of groups, including echinoderms21,22,23,24. In the aftermath of the end-Devonian extinction, it has been recently determined that vertebrates experienced long-term reduction in body size16. The appearance of post-extinction size reduction in crinoids during this crucial time was thus expected. However, the observed trends of increasing mean crinoid body size do not match these predictions. This is surprising because it has been argued that such trends are expected to occur during stable times at some distance from recovery intervals16. Despite hypoxic/anoxic events, global carbonate crisis and perturbation of the global carbon cycles associated with the Late Devonian extinction events14, crinoids not only were diversifying markedly, experiencing only background extinction19,20, but also exhibited a trend toward larger mean sizes at the macroevolutionary scale. Notwithstanding, some clade-dependent (Fig. 3B) and/or short-term within-lineage size decrease (not visible at the scale of this study) associated with these extinctions cannot be excluded.

The observed class-level pattern is not consistent with the existence of an active, driven trend. Instead, a pattern, where both the mean and variance increase over evolutionary time without changing minimum size, suggests a passive Brownian diffusion-like process away from a lower size bound25. Interestingly, recent study demonstrated that the morphologic diversification within the eucladid subclade during the Devonian-early Carboniferous can be also characterized by the Brownian diffusion-like trajectory26. At the lower taxonomic level, the body size distributions either resemble Brownian diffusion model or random walks and stasis. However, due to the small number of bins, individual statistical model-fitting approaches25, enabling detection of directional trends in time series, cannot be performed.

It has been hypothesized that the early Mississippian radiation of crinoids resulted from multiple factors20: (i) expansion of Tournaisian carbonate-ramp settings following the end-Frasnian extinction of coral-stromatoporoid reefs; (ii) predatory release in the Tournaisian after the end-Famennian extinction of durophagous fishes, and (iii) increased primary productivity in the Tournaisian. To some extent the same factors might have also contributed to the passive expansion of crinoids into larger body-size niches. Additionally, increased mean size in some crinoids, although likely not actively driven, might have been also beneficial against the newly evolving Mississippian-style fish predators. Following the Hangenberg large-scale extinction of shearing fish predators, a number of unique and novel fish taxa with crushing dentition diversified in the Mississippian inducing escalatory evolution among benthic invertebrates17,27,28. Indeed, many innovations that potentially reflected anti-predatory adaptations were recognized. Among them are: (i) semi-infaunal lifestyle and increases in ornamentation and spinosity in brachiopods29, (ii) shell reinforcement and increase in shell size in bivalves30, (iii) origins of infaunal life habit in gastropods30. Anti-crushing defences in the calyx have been also documented in the Mississippian camerates31,32. Interestingly, some authors33 argued that increased predation pressure from the Mississippian-style durophagous fishes also led to a size refuge by increasing effective theca size of two early Mississipian crinoid genera (Agaricocrinus, Dorycrinus).

Methods

We compiled a database of calyx sizes for 262 crinoid genera occurring in the Frasnian-Visean interval (details in Supplementary Materials). Calyx, defined from the top of the stalk to the position where the arms become free, is the most important morphological element in crinoids. It contains most of the visceral organs and tissues. Crinoid calyces commonly display high fossilization potential and are of diagnostic importance. Not surprisingly, the crinoid calyx is considered a good proxy for the overall crinoid body size21. Biovolume of calyces were estimated from published figures of type species of holotypes using standard volume calculations for different geometric solids (Supplementary Figs S1–S11). The type species of holotypes is widely considered an unbiased estimate of the median body size of species within a genus34. Furthermore, the inclusion of image-derived data in macroevolutionary studies is considered biologically meaningful34, even though such an approach is affected by a number of biases, which are, however, small and consistent across time and taxa. Two approaches were used in our analyses. In the first approach, we used only one volume estimate for the entire stratigraphic range of a given genus following proposed methodology4. This approach assumes that the size of the holotype of type species is representative for the genus throughout its duration. We also applied a per-occurrence and per-genus approach in that we compared body sizes of the holotypes of type species described from the Frasnian-Visean interval only (237 specimens in total), and treated all body size estimations as independent data points (i.e., without artificial extension of the crinoid biovolume of the type species throughout the entire stratigraphic range of genus). All estimated calyx volumes were subjected to various statistical tests (Shapiro-Wilk normality test, Mann-Whitney U-tests for pairwise stages with Bonferroni correction, significance levels α = 0.05) and linear regressions [Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) and Reduced Major Axis (RMA)]. Comparisons were also made between sister clades35, which are nested at different taxonomic levels to further dissect which (if any) lineage(s) are driving the overall pattern and/or if any lineages are characterized by dynamics that differ from the predominant trend among the Crinoidea. For a more detailed methodology see Supplementary Materials.

References

Peters, R. H. The Ecological Implications of Body Size. (Cambridge Univ. Press, Cambridge, 1983).

Harries, P. J. & Knorr, P. O. What does the ‘Lilliput Effect’ mean? Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaecol. 284, 4–10, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palaeo.2009.08.021 (2009).

Wade, B. S. & Twitchett, R. J. Extinction, dwarfing and the Lilliput effect. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaecol. 284, 1–3, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palaeo.2009.08.019 (2009).

Heim, N. A., Knope, M. L., Schaal, E. K., Wang, S. C. & Payne, J. L. Cope’s rule in the evolution of marine animals. Science 347, 867–870, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1260065 (2015).

Sallan, L. & Galimberti, A. K. Body-size reduction in vertebrates following the end-Devonian mass extinction. Science 350, 812–815, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aac7373 (2015).

Hone, D. W. E. & Benton, M. J. The evolution of large size: how does Cope’s Rule work? Trends Ecol. Evol. 20, 4–6, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2004.10.012 (2005).

Jablonski, D. Body-size evolution in Cretaceous molluscs and the status of Cope’s rule. Nature 385, 250–252, https://doi.org/10.1038/385250a0 (1997).

Twitchett, R. J. The Lilliput effect in the aftermath of the end-Permian extinction event. Palaeogeogr., Palaeoclimatol., Palaecol. 252, 132–144, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palaeo.2006.11.038 (2007).

Butler, R. J. & Goswami, A. Body size evolution in Mesozoic birds: little evidence for Cope’s rule. J. Evol. Biol. 21, 1673–1682, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1420-9101.2008.01594.x (2008).

Monroe, M. J. & Bokma, F. Little evidence for Cope’s rule from Bayesian phylogenetic analysis of extant mammals. J. Evol. Biol. 23, 2017–2021, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1420-9101.2010.02051.x (2010).

Urbanek, A. Biotic crises in the history of Upper Silurian graptoloids: A Palaeobiological model. Historical Biology 7, 29–50 (1993).

McGhee, G. Jr. The late Devonian mass extinction: the Frasnian/Famennian crisis 1–378. (Columbia University Press, 1996).

Racki, G. Toward understanding Late Devonian global events: few answers, many questions. Developments in Palaeontology and Stratigraphy 20, 5–36, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0920-5446(05)80002-0 (2005).

Kaiser, S. I., Aretz, M. & Becker, R. T. The global Hangenberg Crisis (Devonian–Carboniferous transition): review of a first-order mass extinction. Geol. Soc. Spec. Publ. 423, 387–437, https://doi.org/10.1144/SP423.9 (2016).

Stigall, A. L. Speciation collapse and invasive species dynamics during the Late Devonian “Mass Extinction”. GSA Today 22, 4–9 (2012).

Sallan, L. C. & Galimberti, A. K. Body-size reduction in vertebrates following the end-Devonian mass extinction. Science 350, 812–815, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aac7373 (2016).

Sallan, L. C., Kammer, T. W., Ausich, W. I. & Cook, L. A. Persistent predator–prey dynamics revealed by mass extinction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108, 8335–8338, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1100631108 (2011).

Segessenman, D. C. & Kammer, T. W. Testing reduced evolutionary rates during the Late Palaeozoic Ice Age using the crinoid fossil record. Lethaia, https://doi.org/10.1111/let.12239 (2017).

Kammer, T. W. & Ausich, W. I. The “Age of Crinoids”: a Mississippian biodiversity spike coincident with widespread carbonate ramps. Palaios 21, 238–248, https://doi.org/10.2110/palo.2004.p04-47 (2006).

Ausich, W. I. & Kammer, T. W. Mississippian crinoid biodiversity, biogeography and macroevolution. Palaeontology 56, 727–740, https://doi.org/10.1111/pala.12011 (2013).

Borths, M. R. & Ausich, W. I. Ordovician-Silurian Lilliput crinoids during the end-Ordovician biotic crisis. Swiss J. Palaeontol. 130, 7–18 (2011).

Jeffery, C. H. Heart urchins at the Cretaceous-Tertiary boundary: a tale of two clades. Paleobiology 27, 140–158, https://doi.org/10.1666/00948373(2001)027<0140:HUATCT>2.0.CO;2 (2001).

Brom, K. R., Salamon, M. A., Ferré, B., Brachaniec, T. & Szopa, K. The Lilliput effect in crinoids at the end of the Oceanic Anoxic Event 2: a case study from Poland. J. Paleontol. 89, 1076–1081, https://doi.org/10.1017/jpa.2016.10 (2015).

Salamon, M. A., Brachaniec, T., Brom, K. R., Lach, R. & Trzęsiok, D. Dwarfism of irregular echinoids (Echinocorys) from Poland during the Campanian-Maastrichtian Boundary Event. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaecol. 457, 323–329, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palaeo.2016.06.029 (2016).

Hunt, G. Fittings and comparing models of phyletic evolution: Random walks and beyond. Paleobiology 32, 578–601 (2006).

Wright, D. F. Phenotypic innovation and adaptive constraints in the evolutionary radiation of Palaeozoic crinoids. Scientific Reports 7, 13745, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-13979-9 (2017).

Sallan, L. C. & Coates, M. I. End-Devonian extinction and a bottleneck in the early evolution of modern jawed vertebrates. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107, 10131–10135, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0914000107 (2010).

Salamon, M. A., Gorzelak, P., Niedźwiedzki, R., Trzęsiok, D. & Baumiller, T. K. Trends in shell fragmentation as evidence of mid-Paleozoic changes in marine predation. Paleobiology 40, 14–23, https://doi.org/10.1666/13018 (2014).

Leighton, L. R. Predationon on brachiopods. (eds Kelley, P. H., Kowalewski, M. & Hansen, T. A.) 215–237 (Springer, 2003).

Kosnik, M. A. et al. Changes in shell durability of common marine taxa through the Phanerozoic: evidence for biological rather than taphonomic drivers. Paleobiology 37, 303–331, https://doi.org/10.1666/10022.1 (2011).

Simpson, C. Species selection and driven mechanisms jointly generate a large-scale morphological trend in monobathrid camerates. Paleobiology 36, 481–496 (2010).

Syverson, V. J. & Baumiller, T. K. Evolutionary response in Paleozoic crinoid arm branching patterns to grazing predators. Geological Society of America Abstracts with Programs 44, 137 (2012).

Thompson, J. R. & Ausich, W. I. Testing for escalation in Lower Mississippian camerate crinoids. Paleobiology 41, 89–107, https://doi.org/10.1017/pab.2014.6 (2015).

Krause, R. A., Stempien, J. A., Kowalewski, M. J. & Miller, A. I. Body size estimates from the literature: Utility and potential for macroevolutionary studies. Palaios 22, 60–73, https://doi.org/10.2110/palo.2005.p05-122r (2007).

Wright, D. F., Ausich, W. I., Cole, S. R., Peter, M. E. & Rhenberg, E. C. Phylogenetic taxonomy and classification of the Crinoidea (Echinodermata). Journal of Paleontology 91, 829–846 (2017).

Acknowledgements

This project was supported by NCN grant no. DEC-2015/17/N/ST10/03069. The project has also been granted by the Leading National Research Centre (KNOW) to the Centre for Polar Studies for the period 2014–2018. Thanks are due to Dr. Andreas Abele (Humboldt Museum, Berlin) and Dr. Tim Ewin (Natural History Museum, London) for access to some museum collections. Comments by two anonymous reviewers greatly improved this paper. We would like to also thank prof. William I. Ausich (Ohio State University), prof. Thomas W. Kammer (West Virginia University) and Dr. Gary D. Webster (Washington State University) for providing some literature.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.G. and M.A.S. designed research; K.B. performed research and analyzed data; K.B. and P.G. contributed to writing this paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Brom, K.R., Salamon, M.A. & Gorzelak, P. Body-size increase in crinoids following the end-Devonian mass extinction. Sci Rep 8, 9606 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-27986-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-27986-x

This article is cited by

-

Basin-scale reconstruction of euxinia and Late Devonian mass extinctions

Nature (2023)

-

Shared patterns in body size declines among crinoids during the Palaeozoic extinction events

Scientific Reports (2021)

-

Geochemical Evidence of First Forestation in the Southernmost Euramerica from Upper Devonian (Famennian) Black Shales

Scientific Reports (2019)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.