Abstract

We aimed to determine the 6-year incidence and risk factors of age-related macular degeneration (AMD) in first and second generations of Singaporean Indians. Baseline examination was conducted in 2007–9 and 6-year propsective follow-up examination of this Indian population in 2013–5. All participants underwent interviews with questionnaires and comprehensive medical and eye examinations. Incidence was age-standardized to Singaporean 2010 census. Risk factors associated with AMD incidence were assessed and compared between first and second generations of immigrants. Among 2200 persons who participated in the follow-up examination (75.5% response rate), gradable fundus photographs were available in 2105. The 6-year age-standardized incidences of early and late AMD were 5.26% and 0.51% respectively. Incident early AMD was associated with cardiovascular disease history (HR 1.59, 95% CI 1.04–2.45), underweight body mass index (BMI) (HR 3.12, 95% CI 1.37–7.14) (BMI of <18.5 vs 18.51–25 kg/m2), heavy alcohol drinking (HR 3.14 95% CI 1.25–7.89) and ARMS2 rs3750847 homozygous genetic loci carrier (HR 2.52, 95% CI 1.59–3.99). We found a relatively low incidence of early AMD in this Singaporean Indian population compared to Caucasian populations. Both first and second-generation Indian immigrants have similar incidence and risk factor patterns for early AMD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) is the leading cause of severe visual impairment globally, accounting for 8.7% of all blindness worldwide1,2,3,4,5,6. It is crucial to understand the population-specific incidence and risk factors of AMD in planning strategies for future healthcare provision of ageing populations. Earlier studies have reported the incidence of early and late AMD ranging from 5 to 10-year follow-ups in the Caucasian6,7,8,9,10,11,12 Chinese13, Japanese14 and Malay15 populations. A range of systemic and ocular risk factors for AMD have been reported, including cigarette smoking16,17,18,19,20,21,22, dyslipidemia16,17,23,24, and the presence of soft drusen and/or pigmentary abnormalities25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36. To the best of our knowledge, no previous prospective studies have been conducted in Indians to assess AMD incidence and its associated risk factors.

Immigrant populations from developing to developed countries may be influenced by changing lifestyles and environmental factors (e.g., Western type diets, increased incidence of smoking etc)37,38. For example, second-generation immigrants of Indians in Singapore39 and Australia40 have a higher prevalence of diabetes-related complications compared to first-generation immigrants likely due to the metabolic impact of a westernized diet41,42. With an increasing number of Asian Indians who have migrated across the world, studying the impact of immigration on AMD incidence may shed insight on further risk factors for AMD.

In addition, genes have been estimated to explain about 50% of the heritability of AMD. There are over 36 genetic loci discovered each with various roles in the development of AMD. In Asians, the genetic loci most strongly attributed to AMD development are the Complement Factor H (CFH) gene and Age-related Macular Susceptibility 2 (ARMS2) / High-temperature requirement A-1 (HTRA1) loci as reported in the Genetics in AMD in Asians (GAMA) consortium43. Earlier studies have shown that the ARMS2 gene has a stronger influence on AMD development compared to the CFH gene44,45. Further work is needed to support this genetic association in the Indian population.

In view of these unanswered questions, we aimed to determine the 6-year incidence and ocular, systemic and genetic risk factors of early and late AMD in Singaporean Indians, and examined these differences between first and second-generation Indian immigrants.

Methods

Study Population

Our study utilised data from the Singapore Indian Eye Study (SINDI), a population-based cohort study of eligible Indian adults with baseline examination conducted from 2007 to 200916. The recruitment methodology of SINDI has been described in detail elsewhere16. SINDI-246 is the 6-year follow-up study (from 2013 to 2015) among Indian adults who participated in the baseline SINDI study. All 3400 participants from SINDI were sent invitation to attend the 6-year follow-up examinations at the Singapore Eye Research Institute (SERI) via telephone, by mail and/or by home visit.

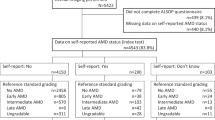

The protocol used in SINDI-2 was identical to that of the SINDI baseline study. Of the 3400 participants from baseline, 486 participants were found to be ineligible to participate in SINDI-2 examination, with 201 deceased, 164 with terminal illnesses, 62 who have migrated, 40 who remained uncontactable, 13 with psychiatric illnesses and 6 who are prisoners. Of the remaining 2914 participants who were considered eligible for the complete follow-up examination, 2200 (75.5% response rate) participated in SINDI-2. After excluding 95 participants (4.3%) with ungradeable photos, data for a remaining 2,105 participants were included in this report (refer to Supplementary Table 1 for comparison between included and excluded patients).

Both baseline and follow-up study were approved by the Institutional Review Board of SingHealth (IRB Approval number: R933/42/2012), Singapore, and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants provided written informed consent.

Immigration Status

Participants were defined as ‘first-generation Indian immigrants’ if they were born in India and as ‘second-generation Indian immigrants’ if they were born in Singapore irrespective of the country of birth of their parents47. We have 793 first-generation immigrants, with 465 of them with parents from India, 290 of them with parents from Malaysia, 39 from other countries and 1 from Indonesia.

Ophthalmic examination and AMD grading

A comprehensive eye examination was performed to obtain participants’ subjective refraction, distance best corrected visual acuity (BCVA) and near vision acuity. Auto-refraction, keratometry, ocular biometry, slit-lamp examination of the anterior segment and tonometry were carried out. Dilated fundus photographs of Early Treatment for Diabetic Retinopathy Study standard fundus fields 1 (centered on the optic disc) and 2 (centered on the fovea) were obtained for both eyes using a digital retinal camera (Canon CR-1 Mark-II Nonmydriatic Digital Retinal Camera, Canon).

Experienced graders in the Centre for Vision Research, University of Sydney, performed AMD grading using the Wisconsin Age-Related Maculopathy Grading System48. All photographs were graded initially in a masked manner, followed by a side-by-side grading of the baseline and six-year photographs. Early AMD as presence of either soft indistinct or reticular drusen or both soft, distinct drusen plus retinal pigment epithelium abnormalities. Late AMD was defined as the presence of neovascular AMD or geographic atrophy (GA). Neovascular AMD included serous or hemorrhagic detachment of the RPE or sensory retina, and the presence of subretinal or sub-RPE hemorrhages or subretinal fibrous scar tissue. GA was characterized by sharply edged, roughly round or oval areas of RPE hypopigmentation, with clearly visible choroidal vessels. The minimum area of GA was 175um in diameter or larger48.

Systemic risk factor assessment

A detailed questionnaire-based interview was administered by trained interviewers with the information collected: contact and demographic information, education, income level, occupation, medical history and lifestyle factors (smoking, alcohol). Alcohol intake frequency was defined as non-drinker (0 days per week of drinking), moderate drinker (1–3 days a week of drinking) and heavy drinker (4–7 days a week of drinking). We did not have complete information on the units or the type of alcohol consumed per day in our population and hence this information was not included in our analysis. Participants’ heights were measured in centimeters using a wall-mounted measuring tape. Weight was measured in kilograms using a digital scale (SECA, model 7822321009: Vogel & Halke, Hamburg, Germany). Systolic and diastolic blood pressure were measured with a digital automatic blood pressure monitor (Dinamap model Pro Series DP110X-RW, 100V2; GE Medical Systems Information Technologies Inc., Milwaukee, USA) with the participant seated after 5 minutes of rest. Non-fasting venous blood was collected for Hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c), serum glucose, C-reactive protein (CRP) and lipid levels. All serum biochemistry tests were performed in the Singapore General Hospital Laboratory on the same day.

Hypertension was defined as systolic blood pressure ≥140 mmHg, diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mmHg or by physician diagnosis. Diabetes was defined as HbA1c >6.5%, casual glucose ≥11.1 mmol/L or use of diabetic medication. Chronic kidney disease was defined as an estimated glomerular filtration rate of less than 60 ml/minute/1.73 m, measured from serum creatinine49. Cardiovascular disease history includes a history of both coronary artery disease (acute myocardial infarction and angina) and stroke.

Genotype

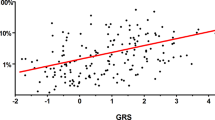

Genotyping was performed using Illumina Human OmniExpres or Human Hap610-Quad Beadchip. The commonly associated SNPs in the CFH and ARMS2/HTRA-1 genes, namely rs1061170 and rs3750847, were not included in the Human610-Quad BeadChips. Hence, we proceeded to test other SNPs within the genes of interest i.e. CFH and ARMS2/HTRA-1 for associations with AMD. We chose the SNP rs10801555 for CFH and rs3750847 for ARMS2 after confirming that they were in perfect linkage disequilibrium (LD; r2 = 1.0) with the Y402H variant (rs1061170) for CFH and rs3750847 for ARMS249. Genetic data of these 2 SNPs was available in 1570 participants.

Statistical Analysis

Baseline characteristics were compared using age-adjusted t-test between individuals who were followed-up and those who did not return for SINDI-2 examination or had ungradable retinal photographs.

Incidence estimates were standardized to the 2010 Singapore census population. Incident early AMD was defined by the appearance at follow-up of either indistinct soft or reticular drusen or the co-presence of both distinct soft drusen and retinal pigmentary abnormalities in either eye of persons in whom no early or late AMD was present at baseline. Incident late AMD was defined by the appearance at follow-up of neovascular AMD or GA in either eye of persons in whom no late AMD lesion was present at baseline.

The associations of potential risk factors with the incidence of early AMD were analysed in separate Generalized Estimating Equation (GEE) models that were adjusted for (1) age and gender (Model 1), and (2) smoking status, hypertension, serum CRP and additional variables that were statistically significant (P < 0.05) in Model 1. Risk factors for late AMD were not assessed due to a low number of cases. For first and second-generation multivariate analysis, multivariable-adjusted analysis including variables that were statistically significant (P < 0.05) in the univariate analysis was done with early AMD as the outcome.

We regarded P values of <0.05 from 2-sided tests to indicate statistical significance. All statistical analyses were performed using the Stata Statistical computer package (STATA Statistical Software, Version 12, Statacorp, College Station, Texas, USA) and R (R Core Team, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Data Availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

Synopsis

Cardiovascular disease, underweight BMI, alcohol drinking and ARMS2 rs3750847 homozygous carrier are risk factors for early age-related macular degeneration (AMD) in Indians. First and second-generation immigrants have similar incidence patterns and risk factors for early AMD.

Results

We included 2105 participants with AMD grading for both baseline and six-year examinations. The baseline characteristics of participants are summarized in Table 1. Participants lost to follow-up at SINDI-2 were more likely to have slightly higher systolic and diastolic blood pressure, higher HbA1c and have lower socioeconomic status, defined as participants with primary or lower education only and individual monthly income <$2,000 Singapore dollars, at baseline, compared to those examined at SINDI-2. (p < 0.05 for all) (Supplementary Table 1).

There are 793 first and 1312 second-generation immigrants who participated in SINDI-2. Compared to the first-generation immigrants, second-generation immigrants were younger, have a higher HbA1c, higher BMI, higher serum CRP, longer axial length and have higher social economic status (p < 0.05 for all).

Incidence of AMD

The age-standardised 6-year incidence of early AMD was 5.26% (n = 107) and 0.51% (n = 10) for late AMD. 0.10% (n = 8) had geographic atrophy and 0.40% (n = 2) had neovascular AMD.

The age-standardized 6-year incidence of early and late AMD were not statistically different between first and second-generation immigrants (early AMD: 5.91% vs 4.21%, p = 0.37, and late AMD: 0.73% vs 0.25%, p = 0.11).

Systemic Risk factors for incident AMD

In the multivariate model, age, cardiovascular disease history, underweight BMI, heavy alcohol intake and ARMS2 rs3750847 homozygous genetic loci carrier remained significantly associated with the incident early AMD (P < 0.05 for all). Age and ARMS2 rs3750847 homozygous genetic loci carrier remained significantly associated with incident early AMD in both first and second generations. Male gender was significantly associated with incident early AMD in first generation immigrants while underweight BMI was significantly associated with incident early AMD in second-generation immigrants (Table 2).

Ocular Risk factors for incident AMD

The age-standardized six-year incidence of neovascular AMD was highest for participants with baseline soft indistinct drusen and pigment (4.72%), followed by those with baseline pigmentary abnormalities (0.87%), intermediate drusen without pigmentary abnormalities (0.33%) and was lowest in those with no AMD at baseline (0.16%) (P < 0.05) (Data not shown). We were not able to assess associations between any of the baseline ocular features with incident GA, due to a very small number of events (n = 2).

Discussion

The six-year age-standardised incidence of early and late AMD was 5.26% and 0.51% respectively in this Singaporean Indian population-based sample. Both first and second-generation immigrants have similar incidence rates of early and late AMD.

The six-year age-standardized cumulative incidence in this Indian population is lower than that of Caucasian populations which range from 8.19%7 to 8.74%8 for early AMD and 0.19%7 to 1.10%8 for late AMD. Rates are comparable to earlier Asian populations; the Singapore Malay Eye Study15 (SiMES) reported 6-year incidence of 6.13% and 0.83% for early and late AMD respectively. The Beijing Eye Study13 reported 5-year early and late AMD incidence at 2.60% and 0.10% respectively. The Hisayama study14 reported 5-year early and late AMD incidence at 8.5% and 0.87% respectively. The SiMES and Beijing studies however had similar mean age at baseline of its study population at 54 years old, compared to our study’s, which is lower than that of the Hisayama’s study at 60 years old. Age range remains an important consideration when comparing the incidence of AMD across studies.

Older age, underweight BMI, cardiovascular disease history, higher alcohol intake and ARMS2 rs3750847 homozygous genetic loci were associated with an increased risk of incident early AMD.

Our finding of an association between underweight BMI and early incident AMD is similar to previous studies. In the Blue Mountains Eye Study8, having a BMI of either lower or higher than the accepted normal range of 20–25 kg/m2 was associated with a significantly increased risk of early AMD. In the Physician’s Health Study50, it reported a J-shaped association between BMI and the incidence of visually significant AMD with the highest incidence among obese men with a BMI > 30 and a lower incidence among the leanest men with BMI < 22. Perhaps deficiencies in important macronutrients such as carotenoids in the diets of underweight people could lead to a higher risk of AMD51. However, this speculation would warrant future studies. Evidence for a history of cardiovascular disease and its association with AMD remains inconsistent52,53,54,55, with chronic inflammation being a possible shared biomechanism for both AMD and cardiovascular disease56.

Heavy alcohol consumption (more than three standard drinks a day) is known to be associated with an increased risk of early AMD of In the Western population57. Alcohol is a known neurotoxin that can result in oxidative brain damage58,59, and could compromise mechanisms which protect against oxidative stress in the retina leading to AMD60,61. We could not evaluate the dose-response curve between alcohol consumption and AMD as we lacked data on alcohol units and types of alcoholic beverage consumed a day.

Homozygous carrier of the ARMS2 rs3750847 genetic loci was significantly associated with incident early AMD. This is similar to the finding from the GAMA consortium which showed associations of ARMS2 rs3750847 with Asian AMD in a genome-wide association study43 and previous Asian studies62,63,64. The role of CFH in early AMD from previous Asian genetic studies remains controversial65,66,67. Our finding adds to existing work and suggest ARMS2 may have a stronger influence on AMD risk in Asians than CFH, owing to the low frequency of the risk allele Y402H (rs1061170) variant in Asians68,69,70,71. Extensive epidemiologic and genetic analyses have led to the conclusion that AMD results from the complex interplay of multiple environmental and genetic factors which in combination account for the development of the phenotype. The high prevalence of the disease implies that interactions amongst multiple genetic and environmental factors influence an individual’s susceptibility to AMD. In our study, there were significant differences in baseline characteristics between the first-generation and second-generation immigrants (HbA1c, obesity, serum CRP and socioeconomic status). Despite the obvious differences in systemic risk profiles, the incidences of early and late AMD and patterns of risk factors for early AMD were interestingly similar between the two generations. This observation is in keeping with our previous publication which reported similar prevalence of AMD among Indian adults living in urban Singapore and rural India despite diverse differences in environmental and systemic risk factor profiles47. Perhaps genetic inheritance, compared to environmental and systemic risk factors, has greater contribution to the risk of developing AMD in Indians. Chakravarthy et al. identified in a meta-analysis that a family history of AMD showed a stronger association with late AMD in comparison to other environmental risk factors such as smoking and a higher BMI72. A previous study in Koreans showed that the presence of ARMS2, but not CFH rs800292 genetic loci, is associated with a greater risk of having exudative AMD compared to other risk factors of spherical equivalent and smoking73. Despite recent studies in AMD genetics which established alleles and haplotypes on chromosome 1 in CFH and on chromosome 10 in ARMS2 as having large influences on the risk for all AMD subtypes in populations of various ethnicities, the combination of these genes alone has been shown to be insufficient to correctly predict the development and progression of this disease74,75. It remains a challenge to assess the effect size of each specific genetic and environmental factors on the risk of AMD. Certain factors may affect predominantly the incidence of late AMD, which would require a much larger sample size to evaluate. The importance of genetic awareness though allows for Individuals with known high-risk genes to be counselled with regards to smoking cessation and also to have a heightened level of self-monitoring of vision. Eye screening in individuals with a strong family history of AMD would also be critical for earlier detection and treatment of disease.

Strengths of the current study include a large population-based, multi-ethnic sample with standardized grading of fundus images and methodology similar to that used in other earlier landmark studies such as the Beaver Dam Eye Study and the Blue Mountain Eye Study for comparison of findings. However, there were limitations to the study as well. Participants lost to follow-up had higher blood pressure, poorer sugar control and were more likely to be living alone. These could be significant risk factors for AMD in the longer run. Also, we only managed to identify 2 participants at the follow-up study with reticular drusen in our entire cohort. This is likely an under-estimation of reticular drusen on colour fundus photo, and hence we decided not to include ‘reticular drusen’ in our eventual analysis. Ideally, we would have collected the blood samples in the fasting state, however logistically it is not feasible in a population study. Nonfasting lipid is believed to be also informative as recent studies, as well as the European Atherosclerosis Society and European Federation of Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine have stated that fasting is not essential for determining lipid profile in relation to predicting cardiovascular disease. most humans spend their day in the nonfasting state, and the nonfasting state might actually be more physiologically relevant in health and disease that the fasting state76,77,78.

In summary, the incidence of early and late AMD in this Singaporean Indian population is lower than that in Caucasian populations. Systemic risk factors for six-year incident early AMD include underweight BMI, cardiovascular disease history, heavy alcohol intake and ARMS2 rs3750847 homozygous genetic loci. Presence of drusen and pigmentary changes at baseline are associated with incidence of late AMD. Although second-generation immigrants have an increased incidence of systemic vascular disease at baseline compared to the first-generation immigrants, both generations appear to have similar incidence of early and late AMD and risk factor patterns of early AMD, suggesting that genetic inheritance, compared to environmental and systemic risk factors, has greater contribution to the risk of developing early AMD in Indians.

References

Klein, R., Klein, B. E. & Cruickshanks, K. J. The prevalence of age-related maculopathy by geographic region and ethnicity. Prog Retin Eye Res. 18, 371–389 (1999).

Mitchell, P., Smith, W., Attebo, K. & Wang, J. J. Prevalence of age-related maculopathy in Australia. The Blue Mountains Eye Study. Ophthalmology. 102, 1450–1460 (1995).

Kawasaki, R. et al. The prevalence of age-related macular degeneration in Asians: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ophthalmology. 117, 921–927 (2010).

Wong, T. Y. et al. The natural history and prognosis of neovascular age-related macular degeneration: a systematic review of the literature and meta-analysis. Ophthalmology. 115, 116–126 (2008).

Wong, W. L. et al. Global prevalence of age-related macular degeneration and disease burden projection for 2020 and 2040: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob Health 2(2), e106–116 (2014).

Klaver, C. C. et al. Incidence and progression rates of age-related maculopathy: the Rotterdam Study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 42, 2237–2241 (2001).

Klein, R., Klein, B. E., Jensen, S. C. & Meuer, S. M. The five-year incidence and progression of age-related maculopathy: the Beaver Dam Eye Study. Ophthalmology 104(1), 7–21 (1997).

Mitchell, P., Wang, J. J., Foran, S. & Smith, W. Five-year incidence of age-related maculopathy lesions: the Blue Mountains Eye Study. Ophthalmology. 109(6), 1092–1097 (2002).

Klein, R., Klein, B. E., Tomany, S. C., Meuer, S. M. & Huang, G. H. Ten-year incidence and progression of age-related maculopathy: The Beaver Dam eye study. Ophthalmology 109(10), 1767–1779 (2002).

Klein, R. et al. Fifteen-year cumulative incidence of age-related macular degeneration: the Beaver Dam Eye Study. Ophthalmology. 114(2), 253–262 (2007).

Buch, H. et al. 14-year incidence, progression, and visual morbidity of age-related maculopathy: the Copenhagen City Eye Study. Ophthalmology. 112(5), 787–798 (2005).

Jonasson, F. et al. 5-year incidence of age-related maculopathy in the Reykjavik Eye Study. Ophthalmology. 112(1), 132–138 (2005).

You, Q. S. et al. Five-year incidence of age-related macular degeneration: the Beijing Eye Study. Ophthalmology. 119(12), 2519–2525 (2012).

Miyazaki, M. et al. The 5-year incidence and risk factors for age-related maculopathy in a general Japanese population: the Hisayama study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 46(6), 1907–1910 (2005).

Cheung, C. M. et al. Six-Year Incidence of Age-Related Macular Degeneration in Asian Malays. Ophthalmology. 124(9), 1305–1313 (2017).

Lavanya, R., Jeganathan, V. S. & Zheng, Y. Methodology of the Singapore Indian Chinese Cohort (SICC) eye study: quantifying ethnic variations in the epidemiology of eye diseases in Asians. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 16(6), 325–336 (2009).

Ferris, F. L. et al. Age-Related Eye Disease Study Research G: A simplified severity scale for age-related macular degeneration: AREDS Report No. 18. Arch Ophthalmol. 123(11), 1570–1574 (2005).

Bressler, S. B., Maguire, M. G., Bressler, N. B. & Fine, S. L. Relationship of drusen and abnormalities of the retinal pigment epithelium to the prognosis of neovascular macular degeneration. Arch Ophthalmol. 108, 1442–1447 (1990).

Holz, F. G. et al. Bilateral macular drusen in age-related macular degeneration: prognosis and risk factors. Ophthalmology. 101, 1522–1528 (1994).

Smith, W. et al. Risk factors for age-related macular degeneration: pooled findings from three continents. Ophthalmology. 108, 697–704 (2001).

Five-year follow-up of fellow eyes of patients with age-related macular degeneration and unilateral extrafoveal choroidal neovascularization. Macular Photocoagulation Study Group. [No authors listed]. Arch Ophthalmol. 111, 1189–1199 (1993).

Baun, O., Vinding, T. & Krogh, E. Natural course in fellow eyes of patients with unilateral age-related exudative maculopathy. Acta Ophthalmol. 71, 398–401 (1993).

Chang, B. et al. Choroidal neovascularization in second eyes of patients with unilateral exudative age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology. 102, 1380–1386 (1993).

Sandberg, M. A., Weiner, A., Miller, S. & Gaudio, A. R. High-risk characteristics of fellow eyes of patients with unilateral neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology. 105, 441–447 (1998).

Roy, M. & Kaiser-Kupfer, M. Second eye involvement in age-related macular degeneration: a four-year prospective study. Eye. 4, 813–818 (1990).

Gregor, Z., Bird, A. C. & Chisholm, I. H. Senile disciform macular degeneration in the second eye. Br J Ophthalmol. 61, 141–147 (1997).

Gass, J. D. M. Drusen and disciform macular detachment and degeneration. Arch Ophthalmol. 90, 207–217 (1973).

Smiddy, W. E. & Fine, S. L. Prognosis of patients with bilateral macular drusen. Ophthalmology. 91, 271–277 (1984).

Bressler, N. M. et al. Five-year incidence and disappearance of drusen and retinal pigment epithelial abnormalities: Waterman Study. Arch Ophthalmol. 113, 301–308 (1995).

Sandberg, M. A., Weiner, A., Miller, S. & Gaudio, A. R. High-risk characteristics of fellow eyes of patients with unilateral neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology. 105(3), 441–447 (1998).

Barbazetto, I. A. et al. Incidence of new choroidal neovascularization in fellow eyes of patients treated in the MARINA and ANCHOR trials. Am J Ophthalmol. 149(6), 939–946 e931 (2010).

Risk factors for choroidal neovascularization in the second eye of patients with juxtafoveal or subfoveal choroidal neovascularization secondary to age-related macular degeneration. Macular Photocoagulation Study Group. [No authors listed]. Arch Ophthalmol. 115(6), 741–747 (1997).

van Leeuwen, R., Klaver, C. C., Vingerling, J. R., Hofman, A. & de Jong, P. T. The risk and natural course of age-related maculopathy: follow-up at 6 1/2 years in the Rotterdam study. Arch Ophthalmol. 121, 519–526 (2003).

Fisher, D. E. et al. Incidence of Age-Related Macular Degeneration in a Multi-Ethnic United States Population: The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Ophthalmology. 123(6), 1297–1308 (2016).

Gupta, S. K. et al. Prevalence of early and late age-related macular degeneration in a rural population in northern India: The INDEYE feasibility study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 48, 1007–11 (2007).

Kulkarni, S. R., Aghashe, S. R., Khandekar, R. B. & Deshpande, M. D. Prevalence and determinants of age-related macular degeneration in the 50 years and older population: A hospital based study in Maharashtra, India. Indian Journal of Ophthalmology. 61(5), 196–201 (2013).

Lara, M., Gamboa, C., Kahramanian, M. I., Morales, L. S. & Bautista, D. E. Acculturation and Latino health in the United States: a review of the literature and its sociopolitical context. Annu Rev Public Health. 26, 367–397 (2005).

Perez-Escamilla, R. & Putnik, P. The role of acculturation in nutrition, lifestyle, and incidence of type 2 diabetes among Latinos. J Nutr. 137(4), 860–870 (2007).

Zheng, Y. et al. Impact of Migration and Acculturation on Prevalence of Type 2 Diabetes and Related Eye Complications in Indians Living in a Newly Urbanised Society. PLoS ONE 7(4), e34829, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0034829 (2012).

Abouzeid et al. Type 2 diabetes prevalence varies by socio-economic status within and between migrant groups: analysis and implications for Australia. BMC Public Health. 13, 252 (2013).

Lee, J. W. R., Brancati, F. L. & Yeh, H.-C. Trends in the prevalence of type 2 diabetes in Asians versus whites: results from the United States National Health Interview Survey, 1997–2008. Diabetes Care. 34(2), 353–357 (2011).

Kaushal, N. Adversities of acculturation? Prevalence of obesity among immigrants. Health Economics. 18(3), 291–303 (2009).

Cheng, C. Y. et al. New loci and coding variants confer risk for age-related macular degeneration in East Asians. Nature communications. 6, 6063 (2015).

Gotoh, Norimoto et al. Correlation between CFH Y402H and HTRA1 rs11200638 genotype to typical exudative age‐related macular degeneration and polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy phenotype in the Japanese population. Clinical & experimental ophthalmology 36(5), 437–442 (2008).

Chen, H. et al. Genetic associations in polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Molecular Vision. 18, 816–829 (2012).

Sabanayagam, C. et al. Singapore Indian Eye Study 2: methodology and impact of migration on systemic and eye outcomes. Clinical & experimental ophthalmology. 1 (2017).

Cheung, C. M. et al. Prevalence and risk factors for age-related macular degeneration in Indians: a comparative study in Singapore and India. Am J Ophthalmol. 155, 764 (2013).

Klein, R. et al. The Wisconsin age-related maculopathy grading system. Ophthalmology. 98(7), 1128–34 (1991).

National Kidney F: K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: evaluation, classification, and stratification. Am J Kidney Dis. 39(2 Suppl 1), S1-266 (2012).

Kanda, A. et al. A variant of mitochondrial protein LOC387715/ARMS2, not HTRA1, is strongly associated with age-related macular degeneration. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 104(41), 16227–32 (2007).

Schaumberg, D. A. et al. Body mass index and the incidence of visually significant age-related maculopathy in men. Arch Ophthalmol. 119, 1259–1265 (2001).

Seddon, J. M. et al. Dietary Carotenoids, Vitamins A, C, and E, and Advanced Age-Related Macular Degeneration. JAMA. 272(18), 1413–1420 (1994).

Alexander, S. L. et al. Annual rates of arterial thromboembolic events in medicare neovascular age-related macular degeneration patients. Ophthalmology. 114(12), 2174–2178 (2007).

Wong, T. Y. et al. Age-related macular degeneration and risk of coronary heart disease: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. Ophthalmology. 114(1), 86–91 (2007).

Wong, T. Y. et al. Age-related macular degeneration and risk for stroke. Annals of Internal Medicine. 145(2), 98–106 (2007).

Wieberdink, R. G. et al. Age-related macular degeneration and the risk of stroke: The Rotterdam Study. Stroke. 42(8), 2138–2142 (2011).

Nowak, J. Z. Age-related macular degeneration (AMD): pathogenesis and therapy. Pharmacological Reports. 58(3), 353 (2006).

Chong, E. W. T. et al. Alcohol consumption and the risk of age-related macular degeneration: a systematic review and meta-analysis. American journal of ophthalmology 145(4), 707–715 (2008).

Agar, E. et al. The effects of ethanol consumption on the lipid peroxidation and glutathione levels in the right and left brains of rats. Int J Neurosci. 113, 1643–1652 (2003).

Cederbaum, A. I. Role of lipid peroxidation and oxidative stress in alcohol toxicity. Free Radic Biol Med. 7, 537–539 (1989).

Katz, M. L. et al. Effects of antioxidant nutrient deficiency on the retina and retinal pigment epithelium of albino rats: a light and electron microscopic study. Exp Eye Res. 34, 339–369 (1982).

Lee, C. S. et al. Acculturation stress and drinking problems among urban heavy drinking Latinos in the Northeast. Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse. 12(4), 308–320 (2013).

Sasaki, M. et al. Gender-specific association of early age-related macular degeneration with systemic and genetic factors in a Japanese population. Scientific reports. 8(1), 785 (2018).

Aoki, A. et al. Risk factors for age-related macular degeneration in an elderly Japanese population: the Hatoyama study. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science. 56(4), 2580–2585 (2015).

Holliday, E. G. et al. Insights into the genetic architecture of early stage age-related macular degeneration: a genome-wide association study meta-analysis. PloS one. 8(1), e53830 (2013).

Chen, J.-H. et al. No association of age-related maculopathy susceptibility protein 2/HtrA serine peptidase 1 or complement factor H polymorphisms with early age-related maculopathy in a Chinese cohort. Molecular Vision. 19, 944–954 (2013).

Nakata, I. et al. Calcium, ARMS2 Genotype, and Chlamydia Pneumoniae Infection in Early Age-Related Macular Degeneration: a Multivariate Analysis from the Nagahama Study. Scientific Reports. 5, 9345 (2015).

Lin, J. M. et al. Complement factor H variant increases the risk for early age-related macular degeneration. Retina. 28(10), 1416–1420 (2008).

Gotoh, N. et al. No association between complement factor H gene polymorphism and exudative age-related macular degeneration in Japanese. Human genetics. 120(1), 139–43 (2006).

Mori, K. et al. Coding and noncoding variants in the CFH gene and cigarette smoking influence the risk of age-related macular degeneration in a Japanese population. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science. 48(11), 5315–9 (2007).

Ng, T. K. et al. Multiple gene polymorphisms in the complement factor h gene are associated with exudative age-related macular degeneration in chinese. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science. 49(8), 3312–7 (2008).

Kondo, N. et al. Complement factor H Y402H variant and risk of age-related macular degeneration in Asians: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ophthalmology. 118, 339–344 (2011).

Chakravarthy, U. et al. Clinical risk factors for age-related macular degeneration: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC ophthalmology. 10(1), 31 (2010).

Jakobsdottir, J. et al. Interpretation of genetic association studies: Markers with replicated highly significant odds ratios may be poor classifiers. PLoS Genet. 5(2), e1000337 (2009).

Swaroop, A. et al. Genetic susceptibility to age-related macular degeneration: A paradigm for dissecting complex disease traits. Hum. Mol. Genet. 16(2), 174–182 (2007).

Driver, S. L. et al. Fasting or nonfasting lipid measurements: it depends on the question. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 67, 1227–1234 (2016).

Langsted, A. et al. Fasting and nonfasting lipid levels: influence of normal food intake on lipids, lipoproteins, apolipoproteins, and cardiovascular risk prediction. Circulation. 118, 2047–2056 (2008).

Stalenhoef, A. F. & de Graaf, J. Association of fasting and nonfasting serum triglycerides with cardiovascular disease and therole of remnant-like lipoproteins and small dense LDL. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 19, 355–361 (2008).

Acknowledgements

National Medical Research Council grants no. 0796/2003 and Biomedical Research Council Grant no. 501/25-5.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conception and design: T.W.Y., C.M.G.C., C.Y.C., Y.Y. Analysis, interpretation of data and writing of manuscript: V.H.X.F., Y.Y., C.M.G.C., Q.D.N., C.S., S.H.L., K.N., J.J.W., P.M.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

41598_2018_27202_MOESM1_ESM.docx

Comparison of Baseline Characteristics between Participants observed and not observed at 6-year examination in the Singapore Indian Study (SINDI)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Foo, V.H.X., Yanagi, Y., Nguyen, Q.D. et al. Six-Year Incidence and Risk Factors of Age-Related Macular Degeneration in Singaporean Indians: The Singapore Indian Eye Study. Sci Rep 8, 8869 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-27202-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-27202-w

This article is cited by

-

Three-dimensional modelling of the choroidal angioarchitecture in a multi-ethnic Asian population

Scientific Reports (2022)

-

Obesity and risk of age-related eye diseases: a systematic review of prospective population-based studies

International Journal of Obesity (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.