Abstract

Spin-valley and electronic band topological properties have been extensively explored in quantum material science, yet their coexistence has rarely been realized in stoichiometric two-dimensional (2D) materials. We theoretically predict the quantum spin Hall effect (QSHE) in the hydrofluorinated bismuth (Bi2HF) nanosheet where the hydrogen (H) and fluorine (F) atoms are functionalized on opposite sides of bismuth (Bi) atomic monolayer. Such Bi2HF nanosheet is found to be a 2D topological insulator with a giant band gap of 0.97 eV which might host room temperature QSHE. The atomistic structure of Bi2HF nanosheet is noncentrosymmetric and the spontaneous polarization arises from the hydrofluorinated morphology. The phonon spectrum and ab initio molecular dynamic (AIMD) calculations reveal that the proposed Bi2HF nanosheet is dynamically and thermally stable. The inversion symmetry breaking together with spin-orbit coupling (SOC) leads to the coupling between spin and valley in Bi2HF nanosheet. The emerging valley-dependent properties and the interplay between intrinsic dipole and SOC are investigated using first-principles calculations combined with an effective Hamiltonian model. The topological invariant of the Bi2HF nanosheet is confirmed by using Wilson loop method and the calculated helical metallic edge states are shown to host QSHE. The Bi2HF nanosheet is therefore a promising platform to realize room temperature QSHE and valley spintronics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The research of atomically thin two-dimensional (2D) materials has been a forefront topic in condensed matter physics since the successful exfoliation of single layer graphene1. A variety of new 2D systems have been proposed in theory and studied in experiment2,3 after the graphene discovery. 2D materials have sparked extensive investigation activities in recent years because of their rich physics and promising applications in optoelectronic devices and spintronics4,5,6,7. Furthermore, 2D materials can be the platforms to realize a variety of new quantum matter states. For example, 2D topological insulators (TIs)8, also known as quantum spin Hall (QSH) insulators, are a new state of quantum matter with an insulating bulk and metallic edge states which are protected by time-reversal symmetry against backscattering. As a matter of fact, graphene was the first proposed system to realize the quantum spin Hall effect (QSHE)9. However, the weak spin-orbit coupling (SOC) strength of carbon in graphene only induces a 10−3 meV bulk band gap which is too small to realize QSHE under ambient temperature10. The experimental realization of 2D TIs is so far limited to the HgTe/CdTe11 and InAs/GaSb12 quantum wells. Recently, a variety of large gap QSH insulators has been theoretically proposed. These large-gap 2D TIs include silicene13, 2D transition metal dichalcogenides14, III-Bi bilayers15, BiF 2D crystals16, Bi4Br4 2D crystals17, ZrTe5 and HfTe5 2D crystals18, tantalum carbide halides19, transition-metal carbides20, functionalized atomic lead films21 and transition-metal halide22. In experiments, the chemical functionalization or decoration is an efficient approach to modulate the physical properties of 2D materials. Compared with the zero-gap graphene, for instance, the hydrogenated or fluorinated graphene is an insulator23,24. In addition, there are several theoretical proposals for QSH insulators with large bulk band gap by decorating Bi-related monolayers using different chemical group25,26,27,28. However, to achieve room temperature functionality the theoretical and experimental searches of QSHE host with large bulk band gaps become critically important29,30.

For this purpose, we propose a hydrofluorinated Bi-based 2D structure namely Bi2HF nanosheet which intrinsically hosts topological band and valley properties. The codecoration of H and F atoms are on opposite sides of Bi buckled honeycomb monolayer. The electronegativity difference between the H and F atoms induces an intrinsic dipole moment which breaks the centrosymmetry in Bi2HF nanosheet. The Bi2HF nanosheet is dynamically and thermally stable, as confirmed by our following phonon and ab initio molecular dynamics calculations. The chemical functionalization with H and F will change electronic structures of the Bi 2D atomic layer. To figure out the coupling of spin and valley, we have used the first principles calculations and an effective Hamiltonian model to investigate the interplay between the intrinsic polarization and SOC. It shows an in-plane Rashba-type spin texture and an out-of-plane spin splitting of the band structure of Bi2HF nanosheet. Furthermore, we have also found that the Bi2HF nanosheet is a 2D topological insulator with a bulk band gap of 0.97 eV which can host room-temperature QSHE. Owing to the noncentrosymmetric structure of Bi2HF nanosheet, we used the Wilson loop method to confirm the topological invariant Z2 = 1. The helical metallic edge states of Bi2HF nanosheet are then revealed by recursive Green’s function approach based on Wannier basis Hamiltonian. The Bi2HF nanosheet is discovered as a promising platform to realize room temperature QSHE and valley spintronics.

Results and Discussion

Geometry, structural stability, and dipolar polarization

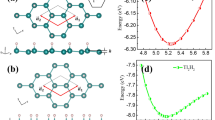

As shown in Fig. 1(a,b), the Bi2HF nanosheet is a 2D honeycomb lattice of buckled Bi atoms bonded with H and F atoms on opposite sides. The bond lengths of Bi-H and Bi-F are 1.84 and 2.08 Å, respectively. Such a functionalized structure of Bi2HF is similar to the hydrofluorinated graphene31,32. Unlike the Bi monolayer and fully hydrogenated or fluorinated Bi monolayer27, the structure of Bi2HF nanosheet is noncentrosymmetric owing to the H and F codecoration on opposite sides of Bi monolayer which breaks inversion symmetry and induces a net out-of-plane dipole moment. However, the switching of polarization directions without breaking chemical bonds is intrinsically impossible in this case. To compute and understand the dipole moment of Bi2HF nanosheet, starting from the centrosymmetric nonpolar fully hydrogenated Bi, we then substitute one by one of all H atoms on one side of the Bi bilayer with F atoms in a 2 × 2 × 1 supercell. The polarization of each structure is calculated using the Berry phase method33 and the results are shown in the Fig. S1. It turns out that the polarization of Bi2HF is 19.0 pC/m which is comparable to 18.5 pC/m of hydrogen and fluorine co-decorated silicene34. To study the relative stability of the Bi2HF nanosheet, the cohesive energy of Bi2HF nanosheet is calculated from the formula defined as

where Etotal is the total energy of optimized system, μ i (i = Bi, H, F) is the chemical potential of Bi, H and F, respectively. We obtain the chemical potential of Bi, H and F elements from bilayer Bi nanosheet, H2 gas, and F2 gas, respectively. The n i (i = Bi, H, F) and N denote the numbers for different elements and total atomic number. The calculated cohesive energy value is found to be −5.35 eV suggesting that the Bi2HF is energetically stable and realizable in experiment. The cohesive energy of Bi2HF is comparable to −4.11 eV of hydrogen and fluorine co-decorated silicene34 and −6.56 eV of graphane24. We have also investigated other geometric configurations of Bi2HF and found that the chair configuration of Bi2HF shown in Fig. 1(a) has lower total energy than the boat and armchair configurations shown in Fig. S2. Thus we will focus on chair configuration in the following discussions.

The atomistic structure of Bi2HF nanosheet (a) top view and (b) side view. The purple, gray and yellow balls denote Bi, H and F atoms, respectively. The big green arrow shows the direction of the intrinsic dipole polarization. (c) The phonon dispersion of Bi2HF nanosheet. (d) The snapshot from AIMD simulation of Bi2HF nanosheet at 300 K after 6 ps.

To check the dynamic stability, the phonon dispersion of hydrofluorinated bismuth nanosheet has been calculated using the density functional perturbation theory (DFPT) approach35. The phonon band structure is shown in Fig. 1(c). There is no imaginary frequency observed in Brillouin zone (BZ) which means that the Bi2HF nanosheet is dynamically stable. We further confirm the thermodynamic stability of Bi2HF nanosheet by performing ab initio molecular dynamics (AIMD) calculation. A 3 × 3 supercell at temperature 300 K with a time step of 1 fs was studied. During the simulation of 6 ps at 300 K, no bond was broken in the honeycomb lattice, suggesting that the structure of Bi2HF nanosheet is thermally stable at room temperature. The snapshot from AIMD calculation of Bi2HF nanosheet at 300 K after 6 ps is shown in Fig. 1(d). One can see that there are no significant disruption or structural reconstruction in Bi2HF nanosheet at 300 K. Our theoretical simulations suggest that Bi2HF nanosheet is promising to be realized in experiment. Here we propose three steps to synthesize Bi2HF nanosheet based on the Bi (111) bilayer, which has been fabricated on the Bi2Te3 substrate in experiments36. In the first step, one can obtain half-fluorinated Bi bilayer by exposure to SF6 plasma23, then transfer half-fluorinated Bi nanosheet onto a new substrate attaching the fluorinated side. At last step, the hydrofluorinated bismuth nanosheet is achieved by exposing the other side surface to low-pressure hydrogen-argon mixture with dc plasma37.

Electronic structures and valley property

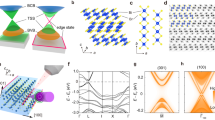

Chemically hydrogenated and fluorinated functionalizations are efficient approaches to change and modify the electronic structures of 2D materials. For instance, the zero band gap of graphene can be tuned to be an insulator when decorated with hydrogen or fluorine23 and the functionalized Sb (111) monolayers are proposed to realize the quantum spin quantum anomalous Hall effect38,39. The electronic band structures and spin textures of Bi2HF nanosheet were calculated. In the absence of SOC, the band structure of Bi2HF nanosheet is shown in Fig. 2(a). It suggests that Bi2HF nanosheet is a narrow-gap semiconductor with a direct band gap of 0.16 eV at K point. Compared to the fully hydrogenated or fluorinated Bi monolayer with a zero band gap in the absence of SOC, this finite band gap of Bi2HF nanosheet is due to the noncentrosymmetric structure. In other words, the intrinsic electric field provided by electronegativity difference between hydrogen and fluorine at opposite sides of bismuth in Bi2HF nanosheet induces the band gap opening. The physical mechanism is similar to the situation of bilayer graphene40,41 and other low dimensional materials42,43 under the external electric field.

The electronic structure of Bi2HF nanosheet. Bands (a) without SOC and (b) with SOC; (c) is the zoom-in of the red box in (b), where the color scale refers to as the out-of-plane S z spin polarization; (d) and (e) are spin textures of the first and second spin-splitted valence bands, respectively. The arrows denote the in-plane spin direction while the colors indicate the out-of-plane spin direction.

The band structure of Bi2HF nanosheet with SOC is shown in Fig. 2(b), and now each band is splitted by the SOC owing to the noncentrosymmetric structure. The SOC inverses the valence band (VB) and conduction band (CB) and opens a 0.97 eV band gap at K point. The band evolution with the SOC strength changing from 0 to 100% is shown in Fig. S3. When the strength of SOC is set to be 15%, the valence band touches with the conduction band on Fermi level and forms a Dirac point at K point. With the continuous increasing of SOC strength, the Dirac point will be gapped and then the band inversion occurs. When the SOC is up to 100%, the band gap is enlarged to 0.97 eV at K point. What is more, there exists Zeeman-type spin splittings for the VBs and CBs at K valley and the Zeeman-type gaps are 0.3 eV for VBs and CBs. This intrinsic spin splitting gap is even larger than the value 0.27 eV of multilayer WSe2 under external electric field44. To understand the large spin-split band gaps of VBs and CBs, the projected band structure with p x and p y orbitals of Bi has been calculated and shown in Fig. S4. The VBs and CBs are dominated by p x and p y orbitals of Bi and the large spin-split in VBs and CBs is due to the strong SOC from p orbitals of Bi element. Moreover, we used HSE06 functional to calculate the band structures both without and with SOC as shown in Fig. S5. The bandgaps of Bi2HF at HSE06 level are 0.15 eV and 1.3 eV for without and with SOC cases, respectively.

The calculated spin textures of the two spin-splitted VBs for the whole BZ are shown in Fig. 2(d,e). One can see the typical Rashba-type spin pattern around the K and −K valleys with the in-plane spin components rotating clockwise or counterclockwise in spin-splitted VBs. For a single VB, the out-of-plane spin components show opposite polarizations at time-reversed valleys and the in-plane spin components display the same chirality at K and −K points. Comparing the spin textures of two spin-split VBs, we find that both the Rashba-like chirality and valley-dependent moment are opposite for the spin-splitted VBs. A similar behavior is found for the spin-splitted CBs.

Effective Hamiltonian model and Berry curvature

To illustrate the origin of the spin texture and valley property, and their interplay with the intrinsic polarization of Bi2HF nanosheet, we derive an effective Hamiltonian model of Bi2HF nanosheet. Based on the first-principles calculations, around the K and −K points at Fermi level, the low-energy band structure is dominated by p x and p y orbitals from Bi atoms (see Fig. S3). So we write the symmetrized basis functions as \(|{\varphi }_{1}\rangle =-\,\frac{1}{2}({{\rm{p}}}_{{\rm{x}}}^{{\rm{A}}}+{i{\rm{\tau }}}_{{\rm{z}}}{{\rm{p}}}_{{\rm{y}}}^{{\rm{A}}}),|{\varphi }_{2}\rangle =\frac{1}{2}({{\rm{p}}}_{{\rm{x}}}^{{\rm{B}}}-{i{\rm{\tau }}}_{{\rm{z}}}{{\rm{p}}}_{{\rm{y}}}^{{\rm{B}}})\), with the τ z representing the valley degree of freedom and A and B are two sites in primitive cell. In the absence of SOC, the low-energy effective Hamiltonian around the K point can be written as

where the Pauli matrix σ i (i = x, y, z) denotes the orbital degree of freedom, τ = ±1 represents the valley degree of freedom of K and −K, the last term describes the staggered sublattice potential induced by inversion symmetry breaking. Compared to the case of graphene9, hydrogenated or fluorinated bismuth monolayer27, the additional mass term leads to an intrinsic band gap in the energy spectrum, which separates the Dirac points at K and −K. It is consistent with band structures obtained from the first-principles calculations.

When the SOC is turned on, additional terms appear in the effective Hamiltonian, namely,

where the Pauli matrix s i (i = x, y, z) denotes the spin degree of freedom, \({{\rm{\lambda }}}_{{\rm{so}}}^{\pm }=\frac{1}{2}({{\rm{\lambda }}}_{so}^{{\rm{A}}}\pm {{\rm{\lambda }}}_{{\rm{so}}}^{{\rm{B}}})\) and \({{\rm{\lambda }}}_{{\rm{R}}}^{\pm }=\frac{1}{2}({{\rm{\lambda }}}_{{\rm{R}}}^{{\rm{A}}}\pm {{\rm{\lambda }}}_{{\rm{R}}}^{{\rm{B}}})\). The first term represents the effective spin orbit interaction and \({{\rm{\lambda }}}_{{\rm{so}}}^{A/B}\) is undetermined material-dependent parameter arising from the interplay of SOC, local orbital energy and hopping integrals. The second term represents the Rashba interaction and \({{\rm{\lambda }}}_{{\rm{R}}}^{A/B}\) is a complex material-dependent Rashba parameter. This effective Hamiltonian has the same form with binary III-V monolayer45. In the case of \({{\rm{\lambda }}}_{{\rm{so}}}^{-}={{\rm{\lambda }}}_{{\rm{R}}}^{-}=0\), one can recover the full hydrogenated or fluorinated bismuth46.

In the first spin-orbit interaction term, the inequivalent A and B sites owing to the noncentrosymmetric structure of Bi2HF nanosheet will introduce a non-zero term \({{\rm{\tau }}{\rm{\lambda }}}_{so}^{+}{\sigma }_{z}\) and this term can be regarded as an effective Zeeman-like valley-dependent magnetic field which removes the spin-degeneracy without mixing spin-up and spin-down states. As a result, the spin-splitted VBs and CBs and a net out-of-plane spin polarization at K valleys are present (as shown in Fig. 2(b,c)). The second Rashba term induces an in-plane circularly rotating spin-texture around each K valley, with opposite charities for spin split VBs (CBs). This is typical Rashba-like behavior, which appears to be valley-independent, in agreement with our first-principles calculations.

To further illustrate the valley properties of Bi2HF nanosheet, the Berry curvature has been calculated using the usual linear response Kubo-like formula47

where f n is the Fermi distribution function, vx,y is the velocity operator, and u nk is the periodic part eigenvector with eigenvalue E nk of the Fourier transformed Wannier Hamiltonian as calculated by projecting the density functional theory (DFT) Hamiltonian onto a Wannier basis48. The calculated out-of-plane Berry curvature of Bi2HF nanosheet is shown in Fig. 3(a), where the opposite signs at K and −K valleys are found.

(a) The out-of-plane Berry curvature on k z = 0 plane in the momentum space of Bi2HF nanosheet. (b) The tracking of the evolution of the WCC between two time-reversal invariant momenta (TRIM) points in the reciprocal space k z = 0 plane. The dashed red line is a reference line to track the number of Wannier center pair.

Quantum spin Hall Effect and helical edge states

Now we focus on the topological property and QSHE in Bi2HF nanosheet. The Bi element is well known for its strong SOC that can drive and stabilize the topological nontrivial states. A variety of Bi-related materials with a large band gap have been proposed and predicted as room temperature QSH insulators16,17,27,28,49. As mentioned above, the strong SOC in Bi2HF nanosheet inverses the valence and conduction bands at K point. This is an important feature of topological insulators. The band topology of Bi2HF nanosheet can be characterized by the Z2 invariant. Z2 = 1 characterizes a nontrivial band topology (corresponding to a QSH insulator), whereas Z2 = 0 represents a trivial band topology. To confirm that the Bi2HF nanosheet is a topological insulator, we need to calculate its Z2 invariant. Since the Bi2HF nanosheet is a noncentrosymmetric structure, the parity method of Fu-Kane formula50 does not work here. Instead, the Wilson loop method should be calculated by Wannier charge centers (WCC) to confirm the topological invariant of Bi2HF nanosheet. As shown in Fig. 3(b), the evolution lines of WCC between two time-reversal invariant momenta (TRIM) of the BZ cross the arbitrary reference line odd number of times in k z = 0 plane, indicating the topological invariant Z2 = 1 and Bi2HF nanosheet is indeed a 2D topological insulator. We also confirm the topological nontrivial feature of Bi2HF by using the HSE06 functional (See Fig. S5(c)).

The helical metallic edge state is a hallmark of the 2D topological insulator. To justify the topological helical metallic edge state of Bi2HF nanosheet, the local density states of two typical semi-infinite edges, namely armchair and zigzag edges, have been calculated using a recursive Green’s function method. As shown in Fig. 4(a,b), it is clear that the helical edge states disperse in the bulk band gap and cross linearly at \(\bar{{\rm{\Gamma }}}\) point. The band structures of the armchair and zigzag nanoribbons with 20 unitcells are calculated using tight-binding method and are shown in the Fig. S6. The results are consistent with our band structures from Green’s function calculations. Note that the left and right edges of the zigzag nanoribbon have different terminations, but the armchair nanoribbon has the same termination for left and right edges. So one can see two Dirac cones at \(\bar{{\rm{\Gamma }}}\) in Fig. S6(b) due to the different chemical potential of left and right edges in the zigzag nanoribbon. These features further prove the nontrivial nature of Bi2HF nanosheet, which is in agreement with Z2 calculations. Remarkably, the Dirac points formed by the helical edge states are very close to Fermi level, which is important for practical spintronics application. Moreover, the giant bulk gap 0.97 eV of Bi2HF nanosheet can stabilize the edge states against the thermally activated carriers, which is beneficial for realizing room-temperature QSHE in Bi2HF nanosheet. To further confirm the robustness of topological properties of Bi2HF nanosheet with respect to temperature, we calculate Z2 invariant and topological metallic edge state using 3 × 3 supercell of Bi2HF after 6 ps AIMD at 300 K. The evolution of WCC of AIMD supercell of Bi2HF nanosheet shows stable topological nontrivial Z2, and the helical metallic edge state of semi-infinite edge of Bi2HF supercell is seen at 300 K as shown in Fig. S7.

Conclusions

In summary, we propose from first-principles that a hydrofluorinated bismuth nanosheet is a 2D topological insulator with a giant bulk band gap of 0.97 eV and it is expected to achieve the room-temperature QSHE. The band topology of Bi2HF nanosheet has been confirmed by Z2 topological invariant using Wilson loop method and the recursive Green’s function calculations also reveal the helical metallic edge states in Bi2HF nanoribbon. The phonon dispersion and AIMD calculations show Bi2HF nanosheet structure is dynamically stable and robust at room temperature. Furthermore, the co-decoration of H and F elements on opposite sides of Bi monolayer induces an intrinsic out-of-plane electric field and thus results in the valley-related properties. The interplay between such intrinsic polarization and SOC generates in-plane Rashba-type spin texture and out-of-plane spin splitting of band structure in Bi2HF nanosheet. The QSHE and valley polarization in Bi2HF nanosheet may find promising applications in future spintronics.

Methods

To investigate the valley and topological properties of Bi2HF nanosheet, we carried out first-principles calculations of DFT as implemented with plane-wave basis set in Vienna ab initio simulation package (VASP)51. The exchange correlation interaction was treated within the generalized gradient approximation (GGA)52 parameterized by the Perdew, Burke, and Ernzerhof (PBE). The energy cutoff of 500 eV was set in all the calculations and the structures are well relaxed until the Hellmann-Feynman forces on all atoms are less than 0.005 eV/Å. A Monkhorst-Pack grid with 17 × 17 × 1 k-points was used for BZ integration. SOC was taken into account self-consistently in terms of the second vibrational procedure53. To overcome the underestimation of bandgap by the PBE functional, we used HSE06 hybrid functional to confirm our results. A large vacuum region of 20 Å was applied along z direction to minimize the interaction between two slabs from the periodic boundary condition. To check the dynamic stability, we present the phonon dispersion of Bi2HF by employing the PHONOPY code54 through the DFPT approach35. To explore the edge states of Bi2HF nanosheet, the effective Hamiltonian was constructed by using maximally localized Wannier function (MLWF) for p orbitals of Bi as implemented in the Wannier90 package48. We used the recursive Green’s function method55 based on MLWF to calculate the local density state of infinite nanosheet. The imaginary part of the surface Green’s function is related to the local density of states (LDOS), from which we can obtain the edge states. Regarding the absence of inversion center in Bi2HF, the Z2 invariant was computed by tracing the WCC using the non-Abelian Berry connection56,57 as implemented in the Z2pack software58.

References

Novoselov, K. S. et al. Electric field effect in atomically thin carbon films. Science 306, 666–669 (2004).

Li, L. et al. Black phosphorus field-effect transistors. Nat. Nanotechnol. 9, 372–377 (2014).

Radisavljevic, B., Radenovic, A., Brivio, J., Giacometti, I. V. & Kis, A. Single-layer MoS2 transistors. Nat. Nanotechnol. 6, 147–150 (2011).

Xiao, D., Liu, G.-B., Feng, W., Xu, X. & Yao, W. Coupled spin and valley physics in monolayers of MoS2 and other group-VI dichalcogenides. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 196802 (2012).

Wang, Q. H., Kalantar-Zadeh, K., Kis, A., Coleman, J. N. & Strano, M. S. Electronics and optoelectronics of two-dimensional transition metal dichalcogenides. Nat. Nanotechnol. 7, 699–712 (2012).

Han, W., Kawakami, R. K., Gmitra, M. & Fabian, J. Graphene spintronics. Nat. Nanotechnol. 9, 794–807 (2014).

Xia, F., Wang, H. & Jia, Y. Rediscovering black phosphorus as an anisotropic layered material for optoelectronics and electronics. Nat. Commun. 5, 4458 (2014).

Hasan, M. Z. & Kane, C. L. Colloquium: topological insulators. Rev. Mod. Phys. 82, 3045 (2010).

Kane, C. L. & Mele, E. J. Quantum spin Hall effect in graphene. Phys. Rev. Lett. 95, 226801 (2005).

Yao, Y., Ye, F., Qi, X.-L., Zhang, S.-C. & Fang, Z. Spin-orbit gap of graphene: First-principles calculations. Phys. Rev. B 75, 041401 (2007).

König, M. et al. Quantum spin Hall insulator state in HgTe quantum wells. Science 318, 766–770 (2007).

Knez, I., Du, R.-R. & Sullivan, G. Evidence for helical edge modes in inverted InAs/GaSb quantum wells. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 136603 (2011).

Liu, C.-C., Feng, W. & Yao, Y. Quantum spin Hall effect in silicene and two-dimensional germanium. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 076802 (2011).

Qian, X., Liu, J., Fu, L. & Li, J. Quantum spin Hall effect in two-dimensional transition metal dichalcogenides. Science 346, 1344–1347 (2014).

Chuang, F.-C. et al. Prediction of large-gap two-dimensional topological insulators consisting of bilayers of group III elements with Bi. Nano Lett. 14, 2505–2508 (2014).

Luo, W. & Xiang, H. Room temperature quantum spin Hall insulators with a buckled square lattice. Nano Lett. 15, 3230–3235 (2015).

Zhou, J.-J., Feng, W., Liu, C.-C., Guan, S. & Yao, Y. Large-gap quantum spin Hall insulator in single layer bismuth monobromide Bi4Br4. Nano Lett. 14, 4767–4771 (2014).

Weng, H., Dai, X. & Fang, Z. Transition-metal pentatelluride ZrTe5 and HfTe5: A paradigm for large-gap quantum spin Hall insulators. Phys. Rev. X 4, 011002 (2014).

Zhou, L. et al. Two-dimensional rectangular tantalum carbide halides TaCX (X = Cl, Br, I): novel large-gap quantum spin Hall insulators. 2D Mater. 3, 035018 (2016).

Zhou, L. et al. Prediction of the quantum spin Hall effect in monolayers of transition-metal carbides MC (M = Ti, Zr, Hf). 2D Mater. 3, 035022 (2016).

Lu, Y., Zhou, D., Wang, T., Yang, S. A. & Jiang, J. Topological properties of atomic lead film with honeycomb structure. Sci. Rep. 6, 21723 (2016).

Zhou, L. et al. New family of quantum spin Hall insulators in two-dimensional transition-metal halide with large nontrivial band gaps. 2D Mater. 15, 7867–7872 (2015).

Zheng, X. et al. Fluorinated graphene in interface engineering of Ge-based nanoelectronics. Adv. Funct. Mater. 25, 1805–1813 (2015).

Sofo, J. O., Chaudhari, A. S. & Barber, G. D. Graphane: A two-dimensional hydrocarbon. Phys. Rev. B 75, 153401 (2007).

Jia, Y.-z et al. First-principles prediction of inversion-asymmetric topological insulator in hexagonal BiPbH monolayer. J. Mater. Chem. C 4, 8750–8757 (2016).

Li, L., Zhang, X., Chen, X. & Zhao, M. Giant topological nontrivial band gaps in chloridized gallium bismuthide. Nano Lett. 15, 1296–1301 (2015).

Song, Z. et al. Quantum spin Hall insulators and quantum valley Hall insulators of BiX/SbX (X = H, F, Cl and Br) monolayers with a record bulk band gap. NPG Asia Mater. 6, e147 (2014).

Ma, Y. et al. Two-dimensional inversion-asymmetric topological insulators in functionalized III-Bi bilayers. Phys. Rev. B 91, 235306 (2015).

Reis, F. et al. Bismuthene on a SiC substrate: A candidate for a high-temperature quantum spin Hall material. Science 357, 287–290 (2017).

Wu, S. et al. Observation of the quantum spin Hall effect up to 100 kelvin in a monolayer crystal. Science 359, 76–79 (2018).

Singh, R. & Bester, G. Hydrofluorinated graphene: Two-dimensional analog of polyvinylidene fluoride. Phys. Rev. B 84, 155427 (2011).

Yang, Y., Ren, W. & Bellaiche, L. Properties of hydrofluorinated carbon-and boron nitride-based nanofilms: A first-principles study. Phys. Rev. B 89, 245439 (2014).

King-Smith, R. D. & Vanderbilt, D. Theory of polarization of crystalline solids. Phys. Rev. B 47, 1651–1654 (1993).

Noor-A-Alam, M., Kim, H. J. & Shin, Y.-H. Hydrogen and fluorine co-decorated silicene: A first principles study of piezoelectric properties. J. Appl. Phys. 117, 224304 (2015).

Gonze, X. & Lee, C. Dynamical matrices, born effective charges, dielectric permittivity tensors, and interatomic force constants from density-functional perturbation theory. Phys. Rev. B 55, 10355 (1997).

Hirahara, T. et al. Interfacing 2D and 3D topological insulators: Bi(111) bilayer on Bi2Te3. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 166801 (2011).

Elias, D. C. et al. Control of graphene’s properties by reversible hydrogenation: evidence for graphane. Science 323, 610–613 (2009).

Zhou, T., Zhang, J., Zhao, B., Zhang, H. & Yang, Z. Quantum spin-quantum anomalous Hall insulators and topological transitions in functionalized Sb (111) monolayers. Nano Lett. 15, 5149–5155 (2015).

Zhou, T. et al. Quantum spin–quantum anomalous Hall effect with tunable edge states in Sb monolayer-based heterostructures. Phys. Rev. B 94, 235449 (2016).

Castro, E. V. et al. Biased bilayer graphene: semiconductor with a gap tunable by the electric field effect. Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 216802 (2007).

Mak, K. F., Lui, C. H., Shan, J. & Heinz, T. F. Observation of an electric-field-induced band gap in bilayer graphene by infrared spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 256405 (2009).

Ren, W., Cho, T., Leung, T. & Chan, C. T. Gated armchair nanotube and metallic field effect. Appl. Phys. Lett. 93, 142102 (2008).

Wu, J. et al. Electric field effect of GaAs monolayer from first principles. AIP Adv. 7, 035218 (2017).

Yuan, H. et al. Zeeman-type spin splitting controlled by an electric field. Nat. Phys. 9, 563 (2013).

Di Sante, D., Stroppa, A., Barone, P., Whangbo, M.-H. & Picozzi, S. Emergence of ferroelectricity and spin-valley properties in two-dimensional honeycomb binary compounds. Phys. Rev. B 91, 161401 (2015).

Liu, C.-C. et al. Low-energy effective hamiltonian for giant-gap quantum spin Hall insulators in honeycomb X-hydride/halide (X = N−Bi) monolayers. Phys. Rev. B 90, 085431 (2014).

Wang, X., Yates, J. R., Souza, I. & Vanderbilt, D. Ab initio calculation of the anomalous Hall conductivity by Wannier interpolation. Phys. Rev. B 74, 195118 (2006).

Mostofi, A. A. et al. wannier90: A tool for obtaining maximally-localised Wannier functions. Comput. Phys. Commun. 178, 685–699 (2008).

Kim, Y., Yun, W. S. & Lee, J. Topological band-order transition and quantum spin Hall edge engineering in functionalized X-Bi (111) (X = Ga, In and Tl) bilayer. Sci. Rep. 6, 33395 (2016).

Fu, L. & Kane, C. L. Topological insulators with inversion symmetry. Phys. Rev. B 76, 045302 (2007).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169 (1996).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865 (1996).

Tong, B. & Sham, L. Application of a self-consistent scheme including exchange and correlation effects to atoms. Phys. Rev. 144, 1 (1966).

Togo, A. & Tanaka, I. First principles phonon calculations in materials science. Scr. Mater. 108, 1–5 (2015).

Sancho, M. L., Sancho, J. L., Sancho, J. L. & Rubio, J. Highly convergent schemes for the calculation of bulk and surface green functions. J. Phys. F 15, 851 (1985).

Soluyanov, A. A. & Vanderbilt, D. Computing topological invariants without inversion symmetry. Phys. Rev. B 83, 235401 (2011).

Yu, R., Qi, X. L., Bernevig, A., Fang, Z. & Dai, X. Equivalent expression of Z2 topological invariant for band insulators using the non-abelian Berry connection. Phys. Rev. B 84, 075119 (2011).

Gresch, D. et al. Z2pack: Numerical implementation of hybrid Wannier centers for identifying topological materials. Phys. Rev. B 95, 075146 (2017).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Key Basic Research Program of China (Grant No. 2015CB921600), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grants No. 51672171), the Eastern Scholar Program from the Shanghai Municipal Education Commission, and the fund of the State Key Laboratory of Solidification Processing in NWPU (SKLSP201703). Special Program for Applied Research on Super Computation of the NSFC-Guangdong Joint Fund (the second phase), the supercomputing services from AM-HPC, the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation and the Fok Ying Tung Education Foundation are also acknowledged. H.G. acknowledges the support of China Scholarship Council.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.G. and W.R. designed the research and wrote the manuscript. H.G. and T.H. performed the computational works and data analysis. A.S., B.W., W.W., X.W. and F.M. discussed results and reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gao, H., Wu, W., Hu, T. et al. Spin valley and giant quantum spin Hall gap of hydrofluorinated bismuth nanosheet. Sci Rep 8, 7436 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-25478-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-25478-6

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.