Abstract

During the Late Bronze Age, the island of Santorini had a semi-closed caldera harbour inherited from the 22 ka Cape Riva Plinian eruption, and a central island referred to as ‘Pre-Kameni’ after the present-day Kameni Islands. Here, the size and age of the intracaldera island prior to the Late Bronze Age (Minoan) eruption are constrained using a photo-statistical method, complemented by granulometry and high-precision K-Ar dating. Furthermore, the topography of Late Bronze Age Santorini is reconstructed by creating a new digital elevation model (DEM). Pre-Kameni and other parts of Santorini were destroyed during the 3.6 ka Minoan eruption, and their fragments were incorporated as lithic clasts in the Minoan pyroclastic deposits. Photo-statistical analysis and granulometry of these lithics, differentiated by lithology, constrain the volume of Pre-Kameni to 2.2–2.5 km3. Applying the Cassignol-Gillot K-Ar dating technique to the most characteristic black glassy andesite lithics, we propose that the island started to grow at 20.2 ± 1.0 ka soon after the Cape Riva eruption. This implies a minimum long-term lava extrusion rate of ~0.13–0.14 km3/ky during the growth of Pre-Kameni.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

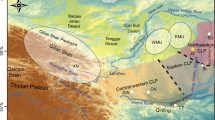

The Late Bronze Age (Minoan) eruption of Santorini (Greece), radiocarbon dated at 1627–1600 BC1, was one of the largest eruptions in the Holocene2 (Fig. 1). The pyroclastic ejecta deposited on land and on the sea floor around the volcano contain a range of lithic clasts derived from pre-existing volcanic formations. The Minoan eruptive products may comprise up to 117–129 km3 bulk volume, corresponding to 78–86 km3 DRE3 (dense rock equivalent). However, this estimate is partly based on the poorly constrained offshore ignimbrites4 and may be regarded as a maximum value.

The landscape of Late Bronze Age Santorini is of great interest to archaeologists, given the presence on the island of the buried Bronze Age town of Akrotiri5. It was originally claimed that prior to the eruption there was an island with a central volcanic cone, possibly as high as 500–800 m6,7, which was disrupted explosively. The destruction of the central part of the island, proposed already by Fouqué8 in 1879, led to caldera formation and resulted in the present-day islands of Thera, Therasia and Aspronisi, which are arranged in a ring around a flooded caldera. Details of caldera formation, and mechanisms of tsunami generation, are discussed by Sparks and Wilson9, Druitt10, and Nomikou et al.11.

Heiken and McCoy12 contradicted the simple scenario of a collapsed central island and, instead, proposed a caldera model similar to those at Somma-Vesuvius or Krakatau (Fig. 1). However, their proposed caldera in the southern part of the present caldera bay, if it ever existed, was shown by Druitt et al.13 to have been long filled-in prior to the Late Bronze Age. Friedrich et al.14 pointed out the occurrence of stromatolites in the Minoan Tuff in the neighbourhood of the northern part of the caldera, interpreting this as evidence of a pre-Minoan shallow bay. Druitt and Francaviglia15, Erikssen et al.16 and recently Athanassas et al.17 refined the likely extension of the pre-Minoan caldera, which may indeed have been restricted to the northern part of the present-day caldera, possibly with a low, narrow strait to the north11 but without an outlet to the southwest.

On the other hand, the presence of abundant lithics, especially clasts of a chemically distinctive black glassy andesite, in the pyroclastic deposits of the Minoan eruption (see below) suggested that the central part of the caldera bay was occupied by an intracaldera island10,14,15,16. We use the term ‘Pre-Kameni’14,17 for this pre-Minoan edifice, which may have been similar to the present-day, post-Minoan islands of Palaea and Nea Kameni, but completely destroyed during the Minoan eruption. The size and age of such a Pre-Kameni island have remained uncertain, although broad estimates of 3 to 5 km3 were proposed3,15 based on the poorly constrained total lithic ejecta18. For comparison, the volume of the present-day Kameni Islands is 3.2 km3 derived from a merged LiDAR bathymetry grid19.

In this paper, by applying a photo-statistical analysis of outcrops complemented by granulometric analysis, we present quantitative results for the volume of the lithic clasts included in the Minoan deposits and, after proportioning their amount, determine the dimensions of the destroyed Pre-Kameni island. The timing of island growth is constrained using high-precision K-Ar dating of the black glassy andesite, which is regarded as the most significant island-forming lithic type9,10,15. The topography of Santorini just before the Minoan eruption is also shown by integrating previous and our own results using a high-resolution digitial elevation model (DEM) of Santorini19.

Late-stage evolution of Santorini

The pre-Minoan landscape of Santorini was dominated by a shallow, flooded caldera formed by the last major explosive eruption before the Minoan, the Cape Riva eruption. A synthesis of published dates for the Cape Riva eruption yields a mean age of 21.8 ± 0.4 ka20. This eruption is thought to have collapsed the pre-existing Skaros-Therasia lava shield13,15. For the subsequent interplinian period which lasted for ~18 ky only minor explosive activity is documented20,21,22.

The 3.6 ka Minoan eruption consisted of four main phases, the deposits of which are denoted A to D by Druitt et al.13. The first phase was a plinian pumice fall7,9,23. A lower, crudely bedded and an upper, unbedded layer, up to 5.5 m thick in total, are collectively named unit A.

During the second phase, interaction with sea water and partial column collapse resulted in phreatomagmatic surges (unit B), ranging in thickness from some dm to up to 12 m13.

In the third phase, significant column collapse produced the most prominent unit of the eruption on land (unit C). This is a coarse-grained, massive, up to 55 m thick, phreatomagmatic ignimbrite up to 55 m thick13, still reflecting magma-water interaction and deposited at low temperatures10,24. The third eruptive phase may have created a tuff cone3,11, possibly a large pyroclastic construct (cf.25) that filled the caldera bay. This phase is thought to coincide with the explosive disruption of the Pre-Kameni island (along with other parts of Santorini), given the occurrence of abundant, evenly distributed lithic clasts up to 10 m in size in the deposit.

In the fourth phase, finer grained, hot ignimbrite (unit D) was produced from multiple vents without phreatomagmatic character. This phase may have been coeval with major caldera collapse9,10. The unit thickens distally up to 80 m offshore and is thought to be the most voluminous Minoan deposit4. The ignimbrites contain thin lithic concentration zones and are capped (or cut) in some places by lithic-rich gravelly beds of fluvial origin up to 5–10 m thick10,13. The presence of the latter indicates considerable potential energy as well as transport distance required for fluvial redeposition of the lithics contained in unit C, B and A, implying a topography which may have been truncated by the caldera collapse only toward the end of phase 4.

Materials, Methods and Results

Petrography and geochemistry of lithic clasts in the Minoan deposits

The Minoan deposits contain a diverse range of juvenile components as well as lithic clasts derived from older parts of Santorini10,13. On the basis of Druitt10, the lithic clasts analysed here are grouped into black glassy andesite, flow-banded rhyolite, and miscellaneous lavas and tuffs (Fig. 2A). Geochemically, the Minoan lithics range from basalt to rhyolite (50.8–71.0 wt.% SiO2). In addition, a dominant low-Ba/Zr group of lithics is distinguished from a characteristic high-Ba/Zr group of clasts of mainly intermediate (andesitic) composition, which are unique in the eruptive history of Santorini since 530 ka10. Among the high-Ba/Zr group, a conspicuous suite of fresh, black, glassy and porphyritic blocks of andesite lava (BGA hereafter) has been interpreted as fragments derived from a pre-Kameni edifice7,9,10. This high-Ba/Zr BGA is distinguished from similar blocks of dark-grey, porphyritic andesite of low-Ba/Zr nature interpreted as fragments of older lava sequences, such as the Therasia lavas13,20. Blocks characterised by a high Ba/Zr ratio also include a variety of slightly altered, light-grey and fine-grained andesite lava and an altered clast of dacitic tuff, grouped under ‘Miscellaneous lavas and tuffs’ (Fig. 2A). A likely origin of these clasts is the early centres of the Akrotiri peninsula (650–550 ka10,13). From the above, it can be concluded that the high-Ba/Zr BGA is the dominant lithology that constituted the Pre-Kameni island.

(A) Ba/Zr vs SiO2 (wt.%) plot of lithic clasts in the Minoan deposits (this study) compared with published data for the Minoan eruptive products (including lithic clasts), the Thera Pyroclastic Formation (2nd explosive cycle), and Santorini lava sequences. Data sources: Druitt10, Druitt et al.13, Fabbro et al.20, Vespa et al.21, Vaggelli et al.22, Barton et al.28, and Huijsmans and Barton29. (B) Photo-statistical analysis of lithic content: (a, b) methodology, (c) cumulative clast area vs cumulative clast number on a sample diagram, (d) summary diagram of lithic proportions in units (A–D) plotted in a box-whisker diagram (numbers are mean ± standard error).

Volumetric analysis of the lithic clasts in the Minoan deposits

76 sites (Fig. 1) have been selected for photo-statistics of the lithic clasts in order to infer the volume of Pre-Kameni. Unit C, with dispersed lithic clasts, is represented by 58 sites; the lithic-poor units of A and B by 4 and 5 sites, respectively, and unit D by 9 sites. The latter includes both the ash-rich, lithic-poor facies and the thin lithic concentration horizons in the ignimbrites. Details of the photo-statistical method are given in Fig. 2B and Appendix 1, and the numerical results are summarized in Table 1.

Although the clast proportion values of the 58 sites of unit C show a great dispersion, the average percentage of the lithic clasts (15.7 vol%) is statistically confident as the standard error for unit C is quite small (1.2%). As for the other units, they are undersampled, but the studied locations are considered to be representative. In units A and B, the percentage of lithic clasts is insignificant (1.8 and 0.8 vol%, respectively), so the standard error is also small (0.6% and 0.2%). In contrast, the average clast proportion increases to 13.8 vol% in unit D (with 5.7% standard error), and the data are even more scattered than in case of unit C. This fact is in accordance with the occasional occurrence of lithic-rich beds. All clast proportions were calculated for the >0.125 mm fraction (see Fig. 2B and Appendix 1).

Granulometric analysis of 4 samples, one from each unit, shows that the finest fraction of <0.125 mm diameter represents an important addition: 39–41 wt% of the bulk material (except the sample from unit A where it is only 6.5%). The proportion of BGA was also measured manually in each fraction of the sieved samples, and in the coarse fraction (>16 mm) of three other unit C locations. Results show that, for unit C, the proportion of BGA ranges between 18% and 31% in the coarsest fraction, whereas in the finer fractions (16–0.125 mm) it varies between 15.9 and 45.1%. These values support that the mean BGA proportion of unit C can be appropriately taken as 30% as proposed by Druitt (2014). As for the other units, we obtained 4.0–18.2% for the BGA proportion in unit D and 0–26.3% in unit A taken all fractions into account, and we did not find BGA clasts in the studied sample of unit B.

In general, both the proportion of lithics and the proportion of BGA within the lithics show a decreasing trend with clast diameter. Based on this trend, we propose that both the proportion of lithics and the proportion of BGA within the lithics in the finest (<0.125 mm) fraction is less than 10%. Accordingly, in our study we calculated with 10% as a maximum value.

K-Ar dating of the black glassy andesite lithic clasts

K-Ar dating of a single BGA sample was performed in the GEOPS laboratory (Orsay, France) using the unspiked Cassignol-Gillot technique, which is especially suitable for dating young samples with low radiogenic argon content (Gillot et al.26; for details, see Appendix 2). The 40Ar-39Ar dating technique was not preferred for the sample, because the irradiation may induce significant 39Ar recoil from the vitrous groundmass and a high production of interferring 36Ar from Ca. Five independent argon analyses of different aliquots of the sample yielded ages ranging between 18.7 ± 3.1 and 21.5 ± 2.0 ka leading to a weighted mean (using the inverse of the variance)27 of 20.2 ± 1.0 ka (Table 2, Fig. 3).

Lava extrusion vs time at Santorini’s central lava dome islands in post-Cape Riva times (post-Minoan volumes are from Nomikou et al.19. Green quadrangle marks the proposed Pre-Kameni, gray quadrangles the Post-Minoan eruptions. Log scale has been used because the inter-eruption durations and lava extrusion values have several order of magnitude differences. Since the exponent in the equation is close to 1, the relationship between lava extrusion and elapsed time is quasi-linear. Insets: sample photograph (right) and thin section image (left, in PPL) of the main constituent of the Pre-Kameni island, the black glassy andesite (BGA).

Discussion

While the caldera morphology of Santorini prior to the Minoan eruption has been recently clarified17 building on the earlier data of Druitt and Francaviglia15, the size and age of a Pre-Kameni island have remained tentative. The rationale for our analysis is that a significant fraction of the lithic clasts, predominantly the BGA included in the Minoan deposits, represents Pre-Kameni, whereas the rest is derived from other destroyed parts of Thera and Therasia. Moreover, dating the BGA can give insights into the timing of Pre-Kameni relative to the Cape Riva eruption.

In order to estimate the volume of the pre-Minoan intra-caldera volcanic island, we proportioned the lithic content between the four Minoan units. At first we considered the maximum estimate of 60 km3 DRE of the on-land and offshore pyroclastic material4. Of this, 41 km3 DRE submarine pyroclastic flow deposits (mostly unit D) corresponds to 54.5 km3 bulk volume4, i.e. the ratio of volume to DRE is 1.33:1. Using this ratio, the on-land DRE values4 correspond to the following bulk volumes: Plinian fall: 3 km3 (2 km3 DRE), on-land ignimbrite: 2 km3 (1.5 km3 DRE), and offshore co-ignimbrite ash: 22.5 km3 (17 km3 DRE), totalling 82 km3 bulk volume.

Additional 18–26 km3 DRE (31–41 km3 bulk volume, i.e. 36 km3 on average) of the intra-caldera infill was proposed by Johnston et al.3, representing units A, B and C (unit D is considered negligible within the caldera). As for their relative proportions, we used the isopach values published by Bond and Sparks7, and Heiken and McCoy12. Units A, B and C have average thicknesses of 2 m, 5 m, and 25 m, respectively, i.e. they represent 6%, 16%, and 78% of the intra-caldera infill. Dividing the bulk volume estimate of Johnston et al.3 by these percentages gives 2.0–2.6 km3 for unit A, 5.0–6.6 km3 for unit B, and 25.0–32.8 km3 for unit C, which are included in the volume values of the Minoan deposits given in Table 1.

This proportioning, along with the ~40% extra lithic content of the finest fraction from granulometric analysis, makes it possible to calculate the total lithics contained in each unit (see Table 1), as well as the BGA (i.e. Pre-Kameni island) volume within the units. An unsolved question is how to divide the 54.5 km3 bulk volume of submarine pyroclastic flow deposits4 between unit C and D. As unit C decreases rapidly in thickness away from the caldera, we propose a ratio of C:D = 1:2 or even 1:4 (both calculations are given). The final standard errors in Table 1 include uncertainty resulting from lithic clast proportions and BGA proportions, but do not take into account the uncertainty of deposit volumes and additional lithics proportion, because the latter values are estimates from the published literature.

As our results show, the total volume of the lithics in the Minoan deposits is ~16–17 km3, more than twice the value suggested by Pyle18. However, within this, the volume of Pre-Kameni, if we envisage that the island was made up entirely of BGA, is significantly smaller, ranging between 2.2 km3 (C:D = 1:4) and 2.5 km3 (C:D = 1:2). As for the calculated range, we consider that the smaller value of 2.2 km3 (i.e. a lower C:D ratio) is more realistic due to the overwhelming presence of unit D in submarine settings. However, assuming that parts of Pre-Kameni may have collapsed into the caldera and were not incorporated into the Minoan deposits, this smaller value must be considered a minimum estimate. This may be offset against a possible, albeit unconstrained, decrease in lithic concentrations with distance from source and uncertainties about the precise volume relationships between units C and D. However, it is the unit C ignimbrite which contains the evenly distributed BGA clasts. Unit D, which is thought to be coeval with caldera collapse during the Minoan eruption, contains lithic clasts of BGA interpreted as predominantly remobilised from unit C. Therefore, it can be inferred that most of the Pre-Kameni island, which was located close to the main vents, was incorporated in unit C.

Such a Pre-Kameni island, on the basis of a new K-Ar age obtained by the K-Ar Cassignol-Gillot technique, seems to have started to grow immediately after the Cape Riva eruption at 20.2 ± 1.0 ka, similar to the present-day Kameni Islands after the Minoan catastrophe11,13. However, the obtained age does not constrain the duration of island growth. The extrusive activity may have declined, and possibly the island was dormant by the Late Bronze Age. This would be consistent with the lack of clasts of BGA with radial jointing (indicative of hot emplacement) in the Minoan products10. Nevertheless, this age allows us to calculate a minimum long-term mean lava extrusion rate for the period from 20.2 to 3.6 ka assuming a constant activity: considering the 2.2–2.5 km3 island volume, the rate is 0.13–0.14 km3/ky. However, because this long-term value is only one seventh of the average growth rate during the much shorter lifetime of the present-day Kameni Islands (~0.9 km3/ky since the Minoan eruption19,28; Fig. 3), it is also possible that Pre-Kameni grew up in a short period at higher lava extrusion rates.

Finally, we visualize the proposed physiography Santorini prior to the Minoan eruption (Fig. 4) using a combined DEM with 10 m resolution offshore and 15 m resolution onshore11. Here, an unconstrained strait in the north, a closed caldera rim in the southwest, a smaller caldera bay (after filling a large part of the present-day southern caldera basin Druitt10; Nomikou et al.11; Athanassas et al.17), and a 2.4 km3 Pre-Kameni island (with ideal low dome shape) in the centre of the flooded bay, are depicted. The SW caldera rim was completed by adding some contours with interpolation, in order to connect Thera and Therasia. The presented DEM reconstruction, i.e. the proposed 3D view of Minoan Santorini, is considered a combination of the obtained quantitative results and qualitative information on the Late Bronze Age topography.

Digital elevation model (DEM) reconstruction of Santorini comparing (a) the present-day topography and (b) the proposed topography prior to the Minoan eruption. The latter shows the reduced size of a Pre-Kameni island, a smaller and shallower caldera harbour restricted to the north, a possibly smaller caldera outlet (dotted blue line) in the north, and a continuous southern caldera rim connecting Thera and Therasia through Aspronisi.

References

Friedrich, W. L. et al. Santorini eruption radiocarbon dated to 1627–1600 B.C. Science 312, 548 (2006).

Crosweller, S. et al. Global database on large magnitude explosive volcanic eruptions (LaMEVE). J. Applied Volcanology 1, 4, https://doi.org/10.1186/2191-5040-1-4 (2012).

Johnston, E. N., Sparks, R. S. J., Phillips, J. C. & Carey, S. Revised estimates for the volume of the Late Bronze Age Minoan eruption, Santorini. Greece. J. Geol. Soc. London 171, 583–590 (2014).

Sigurdsson, H., Carey, S., Alexandri, G., Vougioukalakis, G. & Croff, K. Marine investigations of Greece’s Santorini volcanic field. EOS Trans Am Geophys Union 87(34), 337–348 (2006).

Marinatos, S. Excavations at Thera I-VII. Athens Archaeological Society, Athens (1967–1974).

Pichler, H. & Kussmaul, S. The calc-alkaline volcanic rocks of the Santorini Group (Aegean Sea, Greece). N. Jb. Miner. Abh. 116, 268–307 (1972).

Bond, A. & Sparks, R. S. J. The Minoan eruption of Santorini, Greece. J. Geol. Soc. London 132, 1–16 (1976).

Fouqué, F. Santorini et ses Eruptions. Masson G (ed), Libraire l’Academie de Medicine, Paris, 440 p. (1879).

Sparks, R. S. J. & Wilson, C. J. N. The Minoan deposits: a review of their characteristics and interpretation. In: Hardy, D. A. et al. (eds) Thera and the Aegean World, III/ 2, 89–99 (Thera Foundation, 1990).

Druitt, T. H. New insights into the initiation and venting of the Bronze-Age eruption of Santorini (Greece), from component analysis. Bull. Volcanol. 76, 794, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00445-014-0794-x (2014).

Nomikou, P. et al. Post-eruptive flooding of Santorini caldera and implications for tsunami generation. Nat. Commun. 7, 13332, https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms13332 (2016).

Heiken, G. & McCoy, F. Caldera development during the Minoan eruption, Thira, Cyclades, Greece. J. Geophys. Res. 89, 8441–8462 (1984).

Druitt, T. H. et al. Santorini Volcano. Geol. Soc. London Mem 19, 165 (1999).

Friedrich, W. L. et al. Existence of a water-filled caldera prior to the Minoan eruption of Santorini, Greece. Naturwissenschaften 75, 567–569 (1988).

Druitt, T. H. & Francaviglia, V. Caldera formation on Santorini and the physiography of the islands in the late Bronze Age. Bull. Volcanol. 54, 484–493 (1992).

Eriksen, U., Friedrich, W. L., Buchardt, B., Tauber, H. & Thomsen, M. S. The Stronghyle caldera: geological, palaeotological and stable isotope evidence from radiocarbon dated stromatolites from Santorini. In: Hardy D. A. et al. (eds) Thera and the Aegean World III/2, 139–150 (Thera Foundation, 1990).

Athanassas, C. D. et al. Evidence from cosmic ray exposure (CRE) dating for the existence of a pre-Minoan caldera on Santorini, Greece. Bull Volcanol 78, 35 (2016).

Pyle, D. M. New estimates for the volume of the Minoan eruption. In: Hardy, D. A. (ed.) Thera and the Aegean World III/2., 113–121 (Thera Foundation, 1990).

Nomikou, P. et al. The emergence and growth of a submarine volcano: the Kameni islands, Santorini (Greece). GeoResJ 1–2, 8–18 (2014).

Fabbro, G. N., Druitt, T. H. & Scaillet, S. Evolution of the crustal magma plumbing system during the build-up to the 22-ka caldera-forming eruption of Santorini (Greece). Bull. Volcanol. 75, 767 (2013).

Vespa, M., Keller, J. & Gertisser, R. Interplinian explosive activity of Santorini Volcano (Greece) during the past 150,000 years. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 153, 262–286 (2006).

Vaggelli, G., Pellegrini, M., Vougioukalakis, G., Innocenti, S. & Francalanci, L. Highly Sr radiogenic tholeiitic magmas in the latest inter-Plinian activity of Santorini volcano, Greece. J. Geophys. Res. 114, B06201, https://doi.org/10.1029/2008JB005936 (2009).

Sigurdsson, H., Carey, S. & Devine, J. D. Assessment of the mass, dynamics, and environmental effects of the Minoan eruption of Santorini Volcano. In: Hardy, D. A. et al. (eds) Thera and the Aegean World III/2, 100–112 (Thera Foundation, 1990).

McClelland E. & Thomas R. A palaeomagnetic study of Minoan age tephra from Thera. In: Hardy D. A. et al. (eds) Thera and the Aegean World III/2, 129–138 (The Thera Foundation, 1990).

Fierstein, J. & Hildreth, W. The plinian eruptions of 1912 at Novarupta, Katmai National Park, Alaska. Bull. Volcanol. 54, 646–684 (1992).

Gillot, P.-Y., Hildenbrand, A., Lefèvre, J.-C. & Albore-Livadie, C. The K/Ar dating method: principle, analytical techniques, and application to Holocene volcanic eruptions in southern Italy. Acta Vulcanol. 18, 55–66 (2006).

Taylor, J. R. An Introduction to Error Analysis. University Science Books, Mill Valley, 270 pp (1982).

Barton, M., Salters, V. J. M. & Huijsmans, J. P. P. Sr-isotope and trace element evidence for the role of continental crust in calc-alkaline volcanism on Santorini and Milos, Aegean Sea, Greece. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 63, 273–291 (1983).

Huijsmans, J. P. P. & Barton, M. Polybaric geochemical evolution of two shield volcanoes from Santorini, Aegean Sea, Greece: evidence for zoned magma chambers from cyclic compositional variations. J. Petrol. 30(3), 583–625 (1989).

Watkins, N. D. et al. Volume and extent of the Minoan tephra from Santorini volcano: New evidence from deep sea sediment cores. Nature 271, 122–126 (1978).

Capaccioni, B. & Sarocchi, D. Computer-assisted image analysis on clast shape fabric from the Orvieto-Bagnoregio ignimbrite (Vulsini District, central Italy): implications on the emplacement mechanisms. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 70(1), 75–90 (1996).

Johnston, E. et al. Stratigraphic Relations of Santorini’s Intracaldera Fill and Implications for the Rate of Post-Caldera Volcanism. J. Geol. Soc. Lond. 172, 323–335 (2015).

Karátson, D., Sztanó, O. & Telbisz, T. Preferred clast orientation in volcaniclastic mass-flow deposits: application of a new photo-statistical method. J. Sedim. Res. 72(6), 823–835 (2002).

Armienti, P. Decryption of igneous rock textures: crystal size distributions tools. In: Putirka, K. D., Tepley, F. J. (eds), Minerals, inclusions and volcanic processes, Reviews in mineralogy and geochemistry. Miner. Soc. Amer. 69, 623–649 (2008).

Shea, T. et al. Textural studies of vesicles in volcanic rocks: an integrated methodology. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 190(3), 271–289 (2010).

Sarocchi, D., Sulpizio, R., Macías, J. L. & Saucedo, R. The 17 July 1999 block-and-ash flow (BAF) at Colima Volcano: new insights on volcanic granular flows from textural analysis. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 204(1), 40–56 (2011).

Jutzeler, M., Proussevitch, A. A. & Allen, S. R. Grain-size distribution of volcaniclastic rocks 1: a new technique based on functional stereology. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 239, 1–11 (2012).

Wohletz, H. K. & Brown, W. K. Particulate size distributions and sequential fragmentation/transport theory. Los Alamos National Laboratory report, LA-UR 95-0371 (1995).

Baddeley, A. J. & Jensen, E. B. V. Stereology: sampling in three dimensions. University of Western Australia. Department of Mathematics and Statistics (2002).

Gillot, P.-Y., Cornette, Y., Max, N. & Floris, B. Two reference materials, trachytes MDO-G and ISH-G, for argon dating (K-Ar and 40Ar/39Ar) of Pleistocene and Holocene rocks. Geostandards Newsletter 16, 55–60 (1992).

Gillot, P.-Y. & Cornette, Y. The Cassignol technique for potassium-argon dating, precision and accuracy: examples from late Pleistocene to recent volcanics from southern Italy. Chem. Geol. 59, 205–222 (1986).

Quidelleur, X., Gillot, P.-Y., Soler, V. & Lefèvre, J. C. K/Ar dating extended into the last millennium: application to the youngest effusive episode of the Teide Volcano (Spain). Geophys. Res. Lett. 28(16), 3067–3070 (2001).

Germa, A., Quidelleur, X., Labanieh, S., Chauvel, C. & Lahitte, P. The volcanic evolution of Martinique Island: insights for the Lesser Antilles arc migration since the Oligocene. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 208, 122–135 (2011).

Hess, J. C. & Lippolt, H. J. Compilation of K-Ar measurements on HD-B1 standard biotite: 1994 status report. In: G. S. Odin (Editor), Calibration of the Phanerozoic Time Scale, IGCP Proj. 196. IUGS Subcomm. on Geochronol., Int. Geol. Correl. Progr., Paris, pp. 19–23 (1994).

Steiger, R. H. & Jäger, E. Subcommission on Geochronology: convention on the use of decay constants in Geo and Cosmochronology. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 36(3), 359–362 (1977).

Acknowledgements

DK, TT and VV thank for the financial support from Hungarian National Grant NKFIH OTKA K115472 and an ELTE open access grant. RG acknowledges financial support from Keele University. Multi-beam data were obtained aboard R/V AEGAEO of HCMR during 2001 (in the framework of GEOWARN project IST-1999-12310) and 2006 (THERA 2006, OCE-0452478, supported by grant from the National Science Foundation). We thank the captain and crew of the R/V AEGAEO for their help and great skills in carrying out the exploration of Santorini Volcano. This is Laboratory of Excellence ClerVolc contribution number 295.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D. Karátson, R. Gertisser and T. Telbisz developed the project and wrote the main text, with significant input by T. Druitt and P. Nomikou. D. Karátson, T. Telbisz, R. Gertisser and Sz. Kósik did the field work (rock sampling and taking photos for the statistical study). X. Quidelleur conducted the K-Ar dating. With input by D. Karátson, V. Vereb and T. Telbisz made the photo-statistics and prepared part of Fig. 2. D. Karátson and V. Vereb prepared Fig. 1. R. Gertisser made the geochemical discrimination and prepared part of Fig. 2. T. Telbisz, D. Karátson, R. Gertisser, and P. Nomikou prepared Fig. 3. T. Telbisz prepared Fig. 4. with input by D. Karátson, T. Druitt and P. Nomikou.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Karátson, D., Gertisser, R., Telbisz, T. et al. Towards reconstruction of the lost Late Bronze Age intra-caldera island of Santorini, Greece. Sci Rep 8, 7026 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-25301-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-25301-2

This article is cited by

-

Revised Minoan eruption volume as benchmark for large volcanic eruptions

Nature Communications (2023)

-

Historical accounts provide insight on the geological evolution of the 20th century eruptions at Santorini volcano, Greece

Bulletin of Volcanology (2023)

-

Eruptive activity of the Santorini Volcano controlled by sea-level rise and fall

Nature Geoscience (2021)

-

Large-scale mass wasting on small volcanic islands revealed by the study of Flores Island (Azores)

Scientific Reports (2018)

-

Multiple timescale constraints for high-flux magma chamber assembly prior to the Late Bronze Age eruption of Santorini (Greece)

Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology (2018)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.