Abstract

Tropical corals live close to their upper thermal limit making them vulnerable to unusually warm summer sea temperatures. The resulting thermal stress can lead to breakdown of the coral-algal symbiosis, essential for the functioning of reefs, and cause coral bleaching. Mass coral bleaching is a modern phenomenon associated with increases in reef temperatures due to recent global warming. Widespread bleaching has typically occurred during El Niño events. We examine the historical level of stress for 100 coral reef locations with robust bleaching histories. The level of thermal stress (based on a degree heating month index, DHMI) at these locations during the 2015–2016 El Niño was unprecedented over the period 1871–2017 and exceeded that of the strong 1997–1998 El Niño. The DHMI was also 5 times the level of thermal stress associated with the ‘pre-industrial’, 1877–1878, El Niño. Coral reefs have, therefore, already shown their vulnerability to the modest (~0.92 °C) global warming that has occurred to date. Estimates of future levels of thermal stress suggest that even the optimistic 1.5 °C Paris Agreement target is insufficient to prevent more frequent mass bleaching events for the world’s reefs. Effectively, reefs of the future will not be the same as those of the past.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As the global climate system warms so do the tropical oceans and that is not good news for coral reefs. Tropical corals live close to their upper thermal limit and relatively small excursions of sea surface temperature (SST) above the average summer maximum can lead to the breakdown of the coral-algal symbiosis1. This mutually beneficial relationship between the coral animal and photosynthetic microscopic plants (zooxathellae, Symbiodinium) is the foundation of modern coral reef ecosystems. The coral host obtains photosynthetic products from the algae and this extra source of cheap energy allows the coral to calcify faster than the natural forces of physical and biological erosion2. The resulting sustained building of calcium carbonate skeletons is the backbone of the reef, providing habitat for many thousands of reef-associated organisms that together make up a tropical coral reef ecosystem3. These ecosystems are a vast storehouse of biodiversity and are estimated to contain about 25% of all marine species4 yet the combined area of the world’s shallow water reefs is only about half the size of France. The loss of the algae, whose photosynthetic pigments provide corals with their colour, results in the coral tissue becoming translucent and the white skeleton is then visible – hence the term ‘coral bleaching’1. Once the thermal stress is removed, there are various outcomes for the coral – some die, some partially die, some recover and some may not be affected at all5. For surviving corals, reproduction rates may be reduced6, growth rates slowed7, and the prevalence of coral diseases increased8. Dead coral are often then overgrown by macroalgae (seaweeds), but eventually erode and breakdown and there can be both immediate and long-term consequences for reef-associated organisms (e.g. decline in fish abundance and change in community make-up9). Mass coral bleaching events, where large tracts of reefs are affected, appears to be a relatively modern phenomenon first reported in the early 1980s10. The major trauma of such events, and their apparent and projected increase in frequency, has significant consequences for the maintenance of present-day reef ecosystems and is recognized as a potentially profound consequence of a rapidly changing global climate1,2,11,12,13.

The link between mass coral bleaching events and unusually warm summer SST is unequivocal and now forms the basis of a global thermal stress monitoring system14,15 (http://coralreefwatch.noaa.gov/satellite/index.php). That mass bleaching events had a global signature and apparent links with El Niño events16 was dramatically confirmed during the 1997–1998 El Niño when bleaching affected nearly every coral reef region17,18. The aggregate level of thermal stress across 47 affected reefs during the 1997–1998 El Niño was unprecedented over the period 1903–199919. Mass coral bleaching events have continued since then, for example, ~50% of Australia’s Great Barrier Reef was affected in 200220, ~80% of Caribbean reefs in 200521 and many globally-distributed sites in 201022,23. In mid-2014 bleaching was reported in the western northern tropical Pacific and progressed through many of the world’s reef systems through 2017, tracking the local seasonal maximum SST at the different reef locations24,25. The major El Niño event of 2015–201626 resulted in significant warming of large areas of the tropical oceans and continued bleaching of substantial areas of reef, including Australia’s Great Barrier Reef in early 201627.

Given this recent extensive coral bleaching associated with the major 2015–2016 El Niño event, which is occurring against a backdrop of global warming, this study aims to (1) document how warming of coral reef SST compares to global average warming, (2) determine the level of thermal stress experienced at 100 reef locations with robust bleaching histories28 in 2015–2016, (3) place the recent thermal stress in an historical context, e.g. how does the level of thermal stress compare with the very strong ‘pre-industrial’ El Niño of 1877–187829,30? and (4) what estimated level of thermal stress might be expected at these selected reef sites, given current warming rates, if global warming is limited to 1.5 °C, 2.0 °C as per the Paris Agreement31 or 3 °C, the trajectory based on the Nationally Determined Contributions of individual nations under the UNFCC32 (NDCs)?

Results

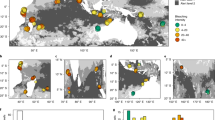

Over the period 1880–2012, the latest IPCC AR5 assessment33 reported warming of global land and sea temperatures by 0.85 °C. Updating this record through 2017, shows an overall warming of 0.92 °C and 2016 was the warmest year on record, exceeding that of 201534. Warming of average annual SST at 1,670 global tropical coral reef sites has largely tracked that of global average temperatures (Fig. 1a) though at a slightly lower rate of 0.65 °C, over the period 1880–2017 (71% of the global average). There is also considerable spatial variability in how the tropical oceans have warmed relative to global average temperatures (Fig. 1b). Warming of the tropical oceans has been substantially less than the global average rate throughout much of the central and eastern tropical Pacific with some small areas (<1%) actually cooling slightly since 1880. 5% of the tropical oceans have warmed <25% of the global average; 55% have warmed 25–75% of the global average; 24% have warmed 75–100% of the global average; with some regions (16% of the tropical oceans) such as the near-equatorial western Indian Ocean warming more than the global average.

(a) Annual average global land and sea temperature (HadCRUT4, red and blue bars) and average annual tropical coral reef sea surface temperature (HadISST1, black line) as anomalies from 1961–1990 average, 1880–2017, and (b) annual tropical sea surface temperature warming as percentage of global land and sea temperature warming, 1880–2017. Black symbols indicate 1-degree latitude by longitude boxes containing 1,670 tropical coral reefs.

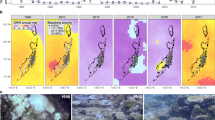

The average degree heating month index (DHMI; a measure of both the magnitude and duration of warm season SST anomalies) of 4.7 for 100 globally-distributed reef locations28 in 2016 was the highest on record between 1871 and 2017 (Fig. 2; Table 1). The second most extreme year was 1998 with a DHMI of 3.9. In 2016 the DHMI ranged from no stress (0.0) at Mauritius and the Cook Islands to a maximum of 14.0 for the Chagos Archipelago. For 20% of locations the thermal stress index was ≤2.0; 53% with thermal stress of 2.0–6.0 and 27% with thermal stress ≥8.0.

The most extreme years of thermal stress at the selected sites have also, almost invariably, been associated with major El Niño events (highlighted in Fig. 2). The very strong ‘pre-industrial’ El Niño of the late 19th century was associated with a DHMI in 1878 of 1.3. The level of thermal stress associated with El Niño’s and major documented coral bleaching has escalated since the late 19th century. Relative to 1878 the level of thermal stress was 1.2 times greater in 1983, 3 times greater in 1998, 2.6 times greater in 2010 and 3.6 times greater in 2016. As El Niño’s usually evolve over two years (as well as their impacts on reefs) if we combine the total thermal stress for these events then for 1982–1983 the level was 1.1 times, 1997–1998 3.2 times, 2009–2010 3.1 times and 2015–2016 4.9 times the thermal stress experienced in 1877–1878 of 1.6 DHMI. There were also regional differences in the temporal evolution of thermal stress, 1871–2017, across the 100 reef locations (Fig. 3; Table S1). The DHMI values were generally lower in the Pacific Ocean (Fig. 3c) and there was an earlier emergence of higher levels of thermal stress in the Caribbean and Atlantic19 (Fig. 3d). All series were significantly correlated (at the 5% level) with the Niño 3.4 index, 1871–2017: r = 0.43 for all 100 locations, 0.48 for the Indian Ocean and Middle East, 0.48 for Southeast Asia, 0.34 for the Pacific Ocean and 0.32 for the Caribbean and Atlantic. Also noteworthy, is the DHMI for 2017 which, although less than in 2016, is still high relative to values in the 1980s, when global mass coral bleaching events first started to emerge (Figs 2 and 3).

The distribution of maximum monthly SST at the 100 locations has also progressively shifted since the late 19th century (Fig. 4a). The maximum monthly SST associated with major El Niño events has similarly changed through time (Fig. 4b). The majority of SST maxima at the 100 reef locations were in the range 29–30 °C during the 1877–1878, 1982–1983 and 1997–1998 events but this has now shifted for 2015–2016 to 30–31 °C.

Post 1950, when the SST data are most reliable, there has been a marked increase in thermal stress at the reef sites since the 1980s that closely matches the increase in global land and sea temperatures (Fig. 5). The most recent 8 years, 2011–2017, experienced greater thermal stress than the 2000s with each decade since the 1980s warmer than the preceding one.

Assuming current linear rates of warming continue for the 100 reef locations (Table S1), the estimated level of thermal stress if global warming is constrained to 1.5 °C is 8.5 DHMI, for 2.0 °C is 14.6 DHMI and for 3.0 °C is 30.1 DHMI (Table 1). These estimated levels of thermal stress are ~7, 11 and 23 times, respectively, the level of thermal stress that these reefs experienced in the pre-industrial event of 1878; and ~2, 3 and 6 times the level of thermal stress experienced in 2016. Regionally, the escalation in thermal stress estimated for the different global warming scenarios is greatest for Southeast Asia and least for the Pacific Ocean (Table 1).

Discussion

Large-scale mass coral bleaching events have increased in frequency, extent and intensity since the latter decades of the 20th century28,35. This breakdown of the fundamental symbiosis at the heart of healthy tropical coral reefs already compromises the future of these charismatic, socio-economically valuable and spectacularly diverse ecosystems. Projections of future stress as the world continues to warm, even under low emissions scenarios, place coral reefs at high to very high risk of continued degradation12,13,36. Even with the aspirational Paris Agreement target of limiting global warming to 1.5 °C above pre-industrial levels, it is estimated that after 2050, 70% of the world’s reefs will be at risk of severe degradation37. Unfortunately, the effects of a warming world is not a future event for coral reefs; it is already happening and compounds ongoing degradation of these dynamic, yet fragile, ecosystems due to overfishing, coastal development and pollution38.

This existing vulnerability has been exemplified in the global mass coral bleaching event of 2015–201624,27,28. In this study we focussed on the thermal histories at 100 globally-distributed reef locations. The 2015–2016 bleaching coincided, as have several recent mass coral bleaching events, with a strong El Niño event, when large parts of the tropical ocean experience unusually warm SST26,39,40. The increased potential for thermal stress causing bleaching on tropical coral reefs during El Niño events is now compounded by warming of the tropical oceans as the global climate system warms33, i.e. baseline SST are now warmer than they were. There is also spatial variation in the magnitude of warming of the tropical oceans41 but overall the level of thermal stress that can potentially result in bleaching is clearly increasing36. The average global land and sea temperature is commonly used to quantify the rate of past and potential future warming33. This metric disguises, however, spatial variations in the rate of warming, with land areas warming faster than the oceans and higher latitudes warming faster than lower latitudes42. Thus, 1 °C of global warming does not equate to 1 °C warming of the tropical oceans41. SST for 1,670 global tropical coral reef locations have warmed 71% of the global average rate over the period 1880–2017.

For the 100 selected coral reef locations examined in this study, the level of thermal stress in 1983 (1.6 DHMI), the first documented mass coral bleaching10, was nearly 25% higher than that experienced during the major 1878 El Niño event29,30. We do not know, due to lack of observations, whether any corals bleached during this ‘pre-industrial’ El Niño but based on recent years (e.g. 1988 and 2006) with similar levels of stress as in 1878 (1.3 DHMI; Fig. 2) for which we have observations, it would seem likely that only some localised bleaching (affecting <15% of locations) might have occurred, if any. Thermal stress during the 1997–1998 El Niño, which affected nearly every coral reef region17,18, was ~3 times that experienced in the late 19th century. For the two years of the most recent, 2015–2016 event, this increased to 4.9 times the ‘pre-industrial’ level of El Niño-induced stress at the 100 selected locations. This increase in the level of thermal stress to coral reefs during El Niño events has occurred with the relatively modest amount of global warming observed to date (1880–2017) of ~0.92 °C. As the world warms we are also seeing a shift in the distribution of SST on tropical coral reefs38 (Fig. 4).

The level of thermal stress (4.7 DHMI) experienced by the 100 coral reef locations in 2016 was unprecedented in the instrumental record, 1871–2017, and exceeded that experienced in 1998 (3.9 DHMI). Given the global extent of coral reefs affected by the 2015–2016 bleaching event24,28, a recurrence of thermal stress of similar magnitude in the near future (as is likely with continued global warming) would be of significant consequence for the maintenance of the world’s reefs. Continued warming of the tropical oceans combined with projected more frequent and severe El Niño events43,44 will continue to exacerbate the levels of thermal stress experienced by coral reefs12. Although there may be regional and local-scale variations in the rates of warming and thermal stress to coral reefs45,46, the overall trajectory will be towards higher levels of thermal stress with, as demonstrated here, each strong El Niño event resulting in a higher level of stress than previous ones and the emergence of significant bleaching in non-El Niño years28.

There is considerable debate as regards the potential for corals (and the coral-algal holobiont) to acclimatize or adapt to warming tropical oceans and increasing frequency and intensity of mass bleaching events47,48. Modelling studies suggest that corals need to increase their thermal tolerance (i.e. temperature at which they bleach) by about 1.5 °C to significantly delay the onset of more frequent bleaching events49. As a consequence, more radical interventions to help corals survive a rapidly changing thermal environment (such as assisted evolution, habitat engineering)50, concentrating management on naturally resistant/resilient reefs51 and a changed approach to reef governance are actively being explored48.

Coral reefs are dynamic ecosystems and can, given time, recover from severe stress events, though often with modified community makeup9. For example, there was a remarkable recovery of coral cover on the isolated Scott Reef off Western Australia 12 years after it was devastated by bleaching in 199852. Unfortunately, this reef was again severely impacted by mass coral bleaching in 201627. Some reefs have witnessed consecutive years of bleaching, e.g. Hawaiian Archipelago in 2014 and 201524 and Australia’s Great Barrier Reef in 2016 and 201753. The interval between thermal stress events has also shortened with the 0.92 °C of global warming observed to date28. Even the aspirational Paris Agreement target of constraining global warming to 1.5 °C above pre-industrial levels is unlikely to be sufficient to prevent drastic modifications and reconfigurations of the community structure and make-up of coral reefs. For the 100 reef locations examined here and given current rates of warming, the 1.5 °C global warming target represents twice the thermal stress they experienced in 2016. The 2 °C global target would result in 3 times the 2016 level of thermal stress and 3 °C, which is currently being tracked with the NDCs32, would be over 6 times the 2016 level of stress. The optimistic global targets of +1.5 °C and 2.0 °C, even if achieved, are unlikely to provide the thermal environment necessary for the maintenance of coral reef communities typical of the mid-20th century.

Data and Methods

Monthly SST were obtained from the HadISST1 data set, January 1871- December 201754 for (a) the 1-degree latitude by longitude boxes containing 100 coral reef locations with robust records of bleaching events, 1980–201628 (Table S1), and 2) 1,670 1-degree latitude by longitude boxes containing tropical coral reefs41. It should be noted that, as with all ‘reconstructed’ SST data sets, due to lack of full observational coverage, the HadiSST1 data set is probably most reliable since the 1950s40. Global land and sea temperature anomalies from the 1961–1990 baseline average were obtained from the HadCRUT4 data set55, 1850–2017. Monthly values of the Niño 3.4 SST index of El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) were obtained from the HadISST1 data set and the NOAA Climate Prediction Center, 1871–2017.

Rates of warming of annual average global land and sea temperature (calculated from HadCRUT4 data set) and tropical coral reef SST (calculated from HadISST1 data set) were compared over the period 1880–2017 based on linear trend analysis33. The ratio of the annual linear trend of tropical SST to global average land and sea temperature (expressed as a percentage) was also mapped throughout the tropical oceans, between 30.5°N-30.5°S, to provide an indication of the spatial variation in warming over the period 1880–2017. For each of the selected 100 coral reef boxes, the level of thermal stress was calculated based on annual degree heating months, 1871–2017, calculated from the HadISST1 data set. This combines both the magnitude and duration of SST anomalies by summing positive monthly anomalies from the 1961–1990 average monthly maximum SST for each year and site. Degree heating month values were totalled over 12 month periods for each location and year for January to December for 72 locations, from December-November at 18 locations, November to October at 8 locations and October to September at 2 locations. These different 12-month periods allowed for Southern Hemisphere locations where seasonal SST maxima can span two calendar years (see Table S1). The degree heating month values at each location were then standardized by the respective, 1961–1990, standard deviation to allow for differences in the variance of the values amongst the 100 reef locations; the median standard deviation of degree heating months for all 100 locations was 0.41° months but some sites, primarily, in the near-equatorial Pacific, have much higher values e.g. 2.07° months for Kiribati and 1.91° months for Ecuador. Standardised values were then averaged to form a Degree Heating Month Index (DHMI) for the 100 reef locations and for four regions: the Caribbean and Atlantic (22 locations), the Indian Ocean and Middle East (28 locations), the Pacific Ocean (36 locations) and Southeast Asia (14 locations) (see Table S1).

The level of thermal stress at the 100 selected locations was also estimated for scenarios where global warming is limited to 1.5 °C, 2.0 °C or 3 °C. These estimates were based on the assumption that the current rate (1880–2017) of SST warming at a particular reef location is maintained into the future. Although this may not necessarily be the case, this simple scaling approach can provide a reasonable indication of what the future may hold56. For each location the ratio of monthly warming relative to global land and sea warming (0.92 °C) was calculated based on linear trend analysis, 1880–2017. Taking this ratio and the amount of warming that has already occurred, monthly SST were then calculated at each site for 1.5°, 2.0 °C and 3 °C of global warming. The DHMI was then calculated (as above) as the average standardised value for these three cases.

Data availability

The HadISST1 data set is available from the UK Meteorological Office Hadley Centre: https://www.metoffice.gov.uk/hadobs/hadisst/index.html; The global land and sea temperatures data set (HadCRUT4) is available from the UK Meteorological Office Hadley Centre: https://www.metoffice.gov.uk/hadobs/hadcrut4/; The Niño 3.4 SST index, 1871–2017, was derived from HadISST1 and the NOAA Climate Prediction Center: http://www.cpc.ncep.noaa.gov/data/indices; Locations and bleaching histories of 100 coral reef locations are available in the Supplementary Material of Hughes et al.31.

References

Baker, A. C., Glynn, P. W. & Riegl, B. Climate change and coral reef bleaching: an ecological assessment of long-term impacts, recovery trends and future outlook. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 80, 435–471 (2008).

Hoegh-Guldberg, O. Climate change, coral bleaching and the future of the world’s coral reefs. Mar. Freshwater Res. 50, 839–866 (1999).

Dubinsky, Z. & Stambler, N. (eds) Coral Reefs: an Ecosystem in Transition. Springer, Dordrecht (2011).

Plaisance, P. L., Caley, M. J., Brainard, R. E. & Knowlton, N. The diversity of coral reefs: what are we missing? Plos One 6, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0025026 (2011).

Marshall, P. A. & Baird, A. H. Bleaching of corals on the Great Barrier Reef; differential susceptibilities among taxa. Coral Reefs 19, 155–163 (2000).

Baird, A. H. & Marshall, P. A. Mortality, growth and reproduction in scleractinian corals following bleaching on the Great Barrier Reef. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 237, 133–141 (2002).

Carilli, J. E., Norris, R. D., Black, B. A., Walsh, S. M. & McField, M. Local stressors reduce coral resilience to bleaching. Plos One 4, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.006324 (2009).

Bruno, J. F. et al. Thermal stress and coral cover as drivers of coral disease outbreaks. Plos Biol. 5, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.0050124 (2007).

Graham, N. A. J. et al. Dynamic fragility of oceanic coral reef ecosystems. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA 103, 8425–8429 (2006).

Glynn, P. W. E. ‘bleaching’ and death of reef corals on the Pacific coast of Panama. Environ. Conserv. 10, 149–154 (1983).

Hughes, T. P. et al. Climate change, human impacts, and the resilience of coral reefs. Science 301, 929–933 (2003).

Frieler, K. et al. Limiting global warming to 2 °C is unlikely to save most coral reefs. Nat. Clim. Change 3, 165–170 (2013).

Gattuso, J.-P. et al. Contrasting futures for ocean and society from different anthropogenic CO2 emissions scenarios. Science 349, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aac4722 (2015).

Liu, G. et al. Reef-scale thermal stress monitoring of coral ecosystems: new 5-km global products from NOAA Coral Reef Watch. Remote Sens. 6, 11579–11606 (2014).

Liu, G. et al. NOAA Coral Reef Watch’s 5km satellite coral bleaching heat stress monitoring product suite version 3 and four-month outlook version 4. Reef Encounter 32, 37–43 (2017).

Williams, E. H. & Bunkley-Williams, L. The world-wide coral reef bleaching cycle and related sources of coral mortality. Atoll Res. Bull. 335, 1–71 (1990).

Wilkinson, C. (ed.) Status of Coral Reefs of the World: 1998. Global Coral Reef Monitoring Network, Australian Institute of Marine Science, Townsville, Australia (1998).

Wilkinson, C. (ed.) Status of Coral Reefs of the World: 2000. Global Coral Reef Monitoring Network, Australian Institute of Marine Science, Townsville, Australia (2000).

Lough, J. M. 1997–98: Unprecedented thermal stress to coral reefs? Geophys. Res. Lett. 27, 3901–3904 (2000).

Berkelmans, R., Dea’th, G., Kininmonth, S. & Skirving, W. J. A comparison of the 1998 and 2002 coral bleaching events on the Great Barrier Reef: spatial correlations, patterns, and predictions. Coral Reefs 23, 74–83 (2004).

Eakin, C. M. et al. Caribbean corals in crisis: record thermal stress, bleaching, and mortality in 2005. Plos One 5, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0013969 (2010).

Guest, J. R. et al. Contrasting patterns of coral bleaching susceptibility in 2010 suggest an adaptive response to thermal stress. Plos One 7, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0033353 (2012).

Alemu, I. J. B. & Clement, Y. Mass coral bleaching in 2010 in the southern Caribbean. Plos One 9 e83829, 10371/journal.pone.0083829 (2014).

Eakin, C. M. et al. Global coral bleaching 2014–2017. Reef Encounter 31, 20–26 (2016).

Eakin, C. M. et al. (2017) Ding, dong, the witch is dead (?) — three years of global coral bleaching 2014–2017. Reef Encounter 32, 31–36 (2017).

L’Heureux, M. L. et al. Observing and predicting the 2015/16 El Niño. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 98, 1363–1382 (2017).

Hughes, T. P. et al. Global warming and recurrent mass bleaching events. Nature 543, 373–377 (2017).

Hughes, T. P. et al. Spatial and temporal patterns of mass bleaching of corals in the Anthropocene. Science 359, 80–83 (2018).

Kiladis, G. N. & Diaz, H. F. An analysis of the 1877–78 ENSO episode and comparison with 1982-83. Mon. Weather Rev. 114, 1035–1047 (1986).

Acietuno, P. et al. The 1877–78 El Niño episode: associated impacts in South America. Climatic Change 92, 389–416 (2009).

Schleussner, C.-F. et al. Science and policy characteristics of the Paris Agreement temperature goal. Nat. Clim. Change. https://doi.org/10.1038/NCLIMATE3096 (2016).

Rogelj, J. et al. Paris Agreement climate proposals need a boost to keep warming well below 2 °C. Nature 543, 631–639 (2016).

Hartmann, D. L. et al. Observations: atmosphere and surface. In: Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the FifthAssessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Stocker, T. F. et al. (eds). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA (2013).

NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information. State of the Climate: Global Climate Report for Annual 2016. https://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/sotc/global/201613 (2017).

Donner, S. D., Rickbeil, G. J. M. & Heron, S. F. A new, high-resolution global mass coral bleaching database. Plos One 12, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0175490 (2017).

Heron, S. F., Maynard, J. A., van Hooidonk, R. & Eakin, C. M. Warming trends and bleaching stress of the world’s coral reefs 1985-2012. Sci. Rep. 6, https://doi.org/10.1038/srep38402 (2016).

Schleussner, C.-F. et al. Differential climate impacts for policy-relevant limits to global warming: the case for 1.5 °C and 2 °C. Earth Syst. Dyn. 7, 327–351 (2016).

Burke, L., Reytar, K., Spalding, M. & Perry, A. Reefs at Risk Revisited World Resources Institute, Washington DC (2011).

McPhaden, M. J. Genesis and evolution of the 1997–98 El Niño. Science 283, 950–954 (1999).

Deser, C., Alexander, M. A., Xie, S.-P. & Phillips, A. S. Sea surface temperature variability: patterns and mechanisms. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci. 2, 115–143 (2010).

Lough, J. M. Small change, big difference: sea surface temperature distributions for tropical coral reef ecosystems, 1950–2011. J. Geophys. Res. 117, C09018 (2012).

Sutton, R. T., Dong, B. & Gregory, J. M. Land-sea warming ration in response to climate change: IPCC AR4 model results and comparison with observations. Geophys. Res. Lett. 34, https://doi.org/10.1029/2006GL028164 (2007).

Power, S., Delage, F., Chung, C., Kociuba, G. & Keay, K. Robust twenty-first-century projections of El Niño and related precipitation variability. Nature 502, 541–545 (2013).

Cai, W. et al. Increasing frequency of extreme El Niño events due to greenhouse warming. Nat. Clim. Change 4, 111–116 (2014).

van Hooidonk, R. et al. Local-scale projections of coral reef futures and implications of the Paris Agreement. Sci. Rep. 6, https://doi.org/10.1038/srep39666 (2017).

Langlais, C. E. et al. Coral bleaching pathways under the control of regional temperature variability. Nat. Clim. Change 7, 839–844 (2017).

Hoegh-Guldberg, O. Coral reef sustainability through adaptation: glimmer of hope or persistent mirage? Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability 7, 127–133 (2014).

Hughes, T. P. et al. Coral reefs in the Anthropocene. Nature 546, 82–90 (2017).

Donner, S. D. Coping with commitment: projected thermal stress on coral reefs under different future scenarios. PLoS ONE, 4, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0005712 (2009).

Anthony, K. et al. New interventions are needed to save coral reefs. Nature Ecology and Evolution 1, 1420–1422 (2017).

Hock, K. et al. Connectivity and systematic resilience of the Great Barrier Reef. PLoS Biol. 15, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.2003355 (2017).

Gilmour, J. P., Smith, L. D., Heyward, A. J., Baird, A. H. & Pratchett, M. S. Recovery of an isolated coral reef system following severe disturbance. Science 340, 69–71 (2013).

Hughes, T. P. & Kerry, J. T. Back-to-back bleaching has now hit two-thirds of the Great Barrier Reef. The Conversation, published online April 12 2017, http://theconversation.com/back-to-back-bleaching-has-now-hit-two-thirds-of-the-great-barrier-reef-76092 (2017).

Rayner, N. A. et al. Global analyses of sea surface temperature, sea ice, and night marine air temperature since the late nineteenth century. J. Geophys. Res. 108, https://doi.org/10.1029/2002JD002670 (2003).

Morice, C. P., Kennedy, J. J., Rayner, N. A. & Jones, P. D. Quantifying uncertainties in global and regional temperature change using an ensemble of observational estimates: the HadCRUT4 data set. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 117, https://doi.org/10.1029/2011JD017187 (2012).

Mitchell, J. F. B., Johns, T. C., Eages, M., Ingram, W. J. & Davis, R. A. Towards the construction of climate change scenarios. Clim. Change 41, 547–581 (1999).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the support of the Australian Institute of Marine Science and the Australian Research Council’s Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the development of the paper. J.M.L. led the analyses and writing. K.D.A. and T.P.H. contributed to the writing and the identification of the 100 reef locations.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lough, J.M., Anderson, K.D. & Hughes, T.P. Increasing thermal stress for tropical coral reefs: 1871–2017. Sci Rep 8, 6079 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-24530-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-24530-9

This article is cited by

-

Gene expression plasticity facilitates acclimatization of a long-lived Caribbean coral across divergent reef environments

Scientific Reports (2024)

-

Studying functions on coral reefs: past perspectives, current conundrums, and future potential

Coral Reefs (2024)

-

Microbial shifts associated to ENSO-derived thermal anomalies reveal coral acclimation at holobiont level

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Asynchrony in coral community structure contributes to reef-scale community stability

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Hidden heatwaves and severe coral bleaching linked to mesoscale eddies and thermocline dynamics

Nature Communications (2023)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.