Abstract

Mitochondrial abnormality is frequently reported in individuals with hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection, but the associated hosts’ mitochondrial genetic factors remain obscure. We hypothesized that mitochondria may affect host susceptibility to HBV infection. In this study, we aimed to detect the association between chronic HBV infection and mitochondrial DNA in Chinese from Yunnan, Southwest China. A total of 272 individuals with chronic HBV infection (CHB), 310 who had never been infected by HBV (healthy controls, HC) and 278 with a trace of HBV infection (spontaneously recovered, SR) were analysed for mtDNA sequence variations and classified into respective haplogroups. Haplogroup frequencies were compared between HBV infected patients, HCs and SRs. Haplogroup D5 presented a higher frequency in CHBs than in HCs (P = 0.017, OR = 2.87, 95% confidence interval [CI] = (1.21–6.81)) and SRs (P = 0.049, OR = 2.90, 95% CI = 1.01–8.35). The network of haplogroup D5 revealed a distinct distribution pattern between CHBs and non-CHBs. A trend of higher viral load among CHBs with haplogroup D5 was observed. Our results indicate the risk potential of mtDNA haplogroup D5 in chronic HBV infection in Yunnan, China.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hepatitis B is one of the world’s leading public health problems caused by hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection. An estimated 257 million people are infected with HBV (defined as hepatitis B surface antigen positive) and an appreciable amount of people die every year due to complications of chronic HBV infection, including cirrhosis and liver cancer. Hepatitis B prevalence is highest in sub-Saharan Africa and East Asia, where between 5–10% of the adult population is chronically infected1 (WHO, Hepatitis B, Fact sheet, http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs204/en/). The course of HBV infection is influenced by age at infection, HBV replication level and host immune status2,3. Recently, several genome-wide association studies (GWASs) and a considerable amount of studies have uncovered genetic factors that may confer susceptibility to hepatitis B4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12, suggesting that host genetic background is most likely to take part in chronic HBV infection. However, the scope of the potential genetic predispositions to HBV infection remains murky, and their role is yet to be determined at functional level.

Mitochondrion is the power plant of all cells and body cells contain variable number of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) copies. The displacement loop (D-loop), also known as mtDNA control region, is necessary for replication and transcription of the mitochondrial genome13. Mitochondria modulate many cell events including energy metabolism, calcium signaling, cell apoptosis and production of free radicals14,15,16. Free radicals can damage mtDNA, resulting in more free radical generation17. Alteration in mitochondrial genetic factors or functions may lead to many kinds of diseases such as psychiatric disorder, neural system dysfunction, myocardial diseases and infectious diseases18,19,20. Whether mitochondrial genetic factor may affect chronic HBV infection has not been investigated.

The HBV genome encodes four partially overlapped open reading frames (ORF), One of the ORFs, the ‘x’ gene, encodes a 17 KDa regulatory protein HBx consisting of 154 amino acids21. HBx is necessary for viral infection as it has been reported to likely play important roles during the establishment of infection, host cell apoptosis, hepatocarcinogenesis and other virus-host cell interactions22. HBx is mainly localised in the cytoplasm23, often co-localising with mitochondria24. In 1995, Zhang et al. demonstrated that HBx can form complex with human mitochondrial HSP60 and HSP70, signifying mitochondria as potential targets of HBx22. HBx can increase mitochondrial calcium uptake and promote store-operated calcium entry (SOCE) to sustain higher cytosolic calcium, which stimulate HBV replication25. Experimental blockage of mitochondrial permeability transition pore caused a decrease in both mitochondrial and cytosolic calcium, and a concomitant inhibition of HBV replication25,26. Taken together, mitochondria may play important role in HBV infection which requires careful investigation.

In this study, we hypothesized that the process of HBV infection may be strongly dependent on host energy production, which is anchored on the mitochondrial genomic infrastructure, hence the link with disease susceptibility. To test this hypothesis, we sequenced the mitochondrial D-loop region of a general population fromYunnan Province, Southwest China. The study population comprised individuals with chronic HBV infection (CHB), spontaneously recovered (SR) subjects after HBV infection and healthy controls (HC) who had never been infected with HBV. We compared their mtDNA haplogroup frequencies and clinical characters. Our results showed that mtDNA haplogroup D5 is associated with chronic HBV infection. Whether haplogroup D5 confers risk to impaired liver function after chronic HBV infection needs further investigation.

Results

Clinical and demographic characteristics of participants

The clinical and demographic characteristics of the 860 individuals enrolled in this study (272 CHBs, 278 SRs and 310 HCs) were summarized in Table 1. The variables analysed include gender, age, serum markers of HBV, serum levels of alanine transaminase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), total bilirubin (TBIL), direct bilirubin (DBIL), total protein (TP) and albumin (ALB). There were more female members in SR group than in CHB and HC groups (P < 0.0001) and the male SR subjects were much older (P < 0.0001) in our hospital-based sample enrollment. There was a significant difference in serum ALT, AST and DBIL levels between CHBs and the other two groups. Gender and age structure did not differ significantly between CHBs and HCs. Among the clinical parameters of liver function, AST level was higher in SRs than in HCs (P = 0.024) (Table 1), possibly influenced by population stratification on behalf of clinical outcomes. No significant difference was observed in other parameters between these two groups.

Association between haplogroup distribution and chronic HBV infection

According to the obtained mtDNA variants information, all 860 individuals could be classified into definite haplogroups, with only a few lineages showing unassigned M and R status (Supplementary Table S1). Principal component results obtained from the mtDNA haplogroup frequency distribution showed that the CHB, SR and HC samples from Yunnan Province were closely clustered (Fig. 1), indicating no apparent population stratification among our study samples.

Principal component analysis of CHBs, SRs and HCs from Yunnan province in Southwest China and the previously reported Han Chinese populations across China. (a) PC map of Han regional populations based on mtDNA haplogroup frequencies. Sample sets in this study were marked by solid triangles. The reported Han Chinese populations (data shown in Supplementary Table S3) were marked by hollow circles. The abbreviations of Han regional populations were the same with those in Supplementary Table S3. (b) Plot of mtDNA haplogroup contribution to the first and second PCs. Abbreviations: PC, principal component.

Among these prevalent haplogroups (each was shared by at least 3% individuals in each population) listed in Table 2, haplogroup D5 had a significantly higher frequency distribution in CHBs than in HCs (P = 0.017, OR = 2.87, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.21–6.81) and SRs (P = 0.049, OR = 2.90, 95% CI = 1.01–8.35). The other haplogroup frequencies showed no significant difference between CHBs and HCs/SRs. There was also no significant difference in the haplogroup frequencies between SRs and HCs (Table 2). With HCs and SRs pooled together, the association of D5 and chronic HBV infection was highly significant (P = 0.008, OR = 2.81, 95% CI = 1.32–6.00) (Table 3). Since HBeAg is an indicator of active replication of HBV in infected patients, and serological conversion of HBeAg positive to HBeAg negative is of great clinical significance, we divided the overall CHB patients into two groups, 62 HBeAg positive (HBeAg (+)) and 210 HBeAg negative (HBeAg (−)), to investigate whether mtDNA haplogroup is associated with HBeAg sero-status among CHBs. No association was observed between mtDNA haplogroup and HBeAg status (Table 4), possibly because of the limited number of samples in this analysis. Overall, these results indicated an association between mtDNA haplogroup D5 and chronic HBV infection.

The network of haplogroup D5 constructed based on variants of the hypervariable segment 1 (HVS-I) (np16024–16400) of the mtDNA control region revealed a distinct distribution pattern between CHBs and the combined controls comprising SRs and HCs. Only two of 27 (7.4%) mtDNA haplotypes belonging to D5 were shared between CHBs and non-CHB controls (Fig. 2).

Network of haplogroup D5 in CHBs and combined controls consists of SRs and HCs. The variant order of the mtDNA control region is arbitrary on the branch. Each circle represents a kind of mtDNA haplogroup. The area of each circle is proportional to the haplogroup frequency. Sample sizes of the smallest and the largest sub-lineages were labeled in the corresponding circles. Length mutation of C-tract in region 16184–16193 was not considered during the network construction. The asterisks denote ancestral nodes of haplogroup D5.

Characterisation of clinical parameters in CHBs according to haplogroups

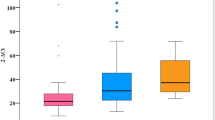

As haplogroup D5 showed a higher frequency in CHBs, we conducted further tests to see whether this haplogroup influences HBV viral load (VL) or indices of liver function. First, we screened the samples from the CHBs belonging to haplogroup D5 (n = 12) and non-D5 (n = 154) for VL based on HBV-DNA. We categorized the CHB individuals according to five VL degrees. The distribution of VL showed that the proportion of CHBs in haplogroup D5 was less than that in non-D5 when the VL was below 1.0 × 106. In the contrary, the proportion of individuals in haplogroup D5 was higher than that in non-D5 in the topmost VL degree (VL > 1.0 × 107) (Fig. 3). We then compared the serum ALT, AST, TBIL, DBIL, TP and ALB levels of CHBs belonging to haplogroup D5 (n = 21) and nonD5 (n = 249 for ALT, AST, TBIL and DBIL; n = 242 for TP and ALB). The overall difference in ALT levels between D5 and non-D5 CHBs was statistically significant (P = 0.02), with the highest ALT level observed in a patient belonging to haplogroup D5. However, when we excluded the highest ALT from D5, the overall difference was not statistically significant. The levels of the other five parameters were not different between D5 and non-D5 CHBs (Fig. 4).

Viral load of serum HBV-DNA in CHBs belonging to haplogroup D5 and non-D5. We divided the viral load into five categories arbitrarily. The horizontal axis represents the viral load of serum HBV-DNA. The vertical axis represents the proportion of participants whose viral load falls in the respective viral load categories among CHBs with D5 or other haplogroup backgrounds.

Clinical parameters of liver function in CHBs belonging to haplogroup D5 and non-D5. Serum levels of ALT (alanine transaminase), AST (aspartate aminotransferase), TBIL (total bilirubin), DBIL (direct bilirubin), TP (total protein) and ALB (albumin) were compared between D5 and non-D5 haplogroup members. Horizontal lines across the plots mark the mean expression level. Asterisk indicates significant difference (P < 0.05).

Discussion

Chronic hepatitis B, caused by HBV infection, is one of the most prevalent infectious diseases globally. The mechanisms underlying acute HBV infection or its progression to chronicity remain largely unknown. It was reported that the outcome of HBV infection does not appear to be determined by variations in the virulence of viral strains, and variation in host genes may partly explain the variability in HBV infection outcomes or the molecular mechanisms of viral clearance27,28. Instead, host factors are more likely to affect the disease outcome11,29,30. Recently, many researchers have tried to investigate host genetic factor that may explain the molecular pathogenesis of HBV infection. These include several genome wide association studies (GWASs) that have identified single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) at several loci linking genetic susceptibility to HBV infection among populations living in HBV endemic areas. Following the first GWAS that investigated host genetic factors associated with chronic hepatitis B in Japan31, other GWASs have been carrying out in China and Korean in succession. Some risk factors such as rs3077 and rs9277535 in HLA-DP, as well as rs2856718 and rs7453920 in HLA-DQ at 6p21.32 were highly replicated in GWASs9,11,12,32,33. At the same time, some new loci were also identified, for instance, the INST10 gene at 8p21.3 and its eQTL SNP rs70009219, indicating that there may be other genetic factors yet to be discovered which contribute to HBV infection and its overall pathology.

In recent years, mitochondrial function, mtDNA variants and mtDNA haplogroup have been widely investigated in many kinds of human diseases18,34,35,36,37 including viral infectious diseases20,38,39. Relationship between low circulating mtDNA contents and increased risk of cirrhosis in HBV infected individuals has been reported40. The rate of D-loop mutations was significantly higher in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) individuals with HBV infection than in normal individuals41. Additionally, several studies have discovered interactions between HBV protein HBx and mitochondria which affects mitochondrial functionality22,24,25.

Although chronic HBV infections are widely spread across the globe, the burden of the disease is disproportional, with places like China bearing the heaviest brunt. We hypothesized that the geographic distribution of mtDNA haplogroup may be associated with this endemicity. In this study, we analysed mtDNA haplogroup distribution in 272 CHB patients, 278 SRs and 310 HCs from Yunnan Province in Southwest China. Our results indicated that mtDNA haplogroup D5 may confer genetic susceptibility to chronic HBV infection (Table 2). When SRs and HCs were put together as a combined control, the risk effect of haplogroup D5 for chronic HBV infection was consistently robust (Table 3). Principal component analysis (PCA) showed that the three sample groups were clustered together, suggesting a limited interference from any sampling bias or population stratification on behalf of mtDNA inheritance.

A large amount of association studies suggested an association between mtDNA haplogroup and many human diseases such as Leber hereditary optic neuropathy (LHON)42,43, sepsis44 and type 2 diabetes mellitus45,46. These studies further showed that the associations were always accompanied by geographically-based diversities. MtDNA haplogroups were also investigated in outcomes of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection and antiretroviral therapy. Haplogroup H, I and K were associated with increased lipoatrophy in European-American and European individuals taking antiretroviral medication. Haplogroup H was also associated with lower likelihood of AIDS progression in Spanish individuals. Several anti-HIV drugs have been reported to induce mitochondrial toxicity47. Our results suggested that haplogroup D5 could be a risk factor for chronic HBV infection in Yunnan Province, Southwest China. However, enrichment of longevity phenotype in haplogroups D4b2b, D4a and D5 in the Japanese population was also reported48. Haplogroup D5 was also associated with esophageal cancer in Han Chinese from the Taihang Mountain area and Chaoshan area49. Transmitochondrial cytoplasmic hybrid (cybrid) cells harboring haplogroup D5 and F were associated with an increased risk of type 2 diabetes45. These reports revealed the role of haplogroup D5 as well as other mtDNA haplogroups more complicate in human diseases.

Interactions between HBeAg and the host were complex during HBV infection. HBeAg may impair both innate and adaptive immune response to promote chronic HBV infection, but the role of HBeAg in natural infection remains largely unknown50,51. Although our results showed haplogroup D5 as a risk factor for chronic HBV infection, we did not observe association between mtDNA haplogroup and HBeAg status in patients chronically infected with HBV, indicating that mtDNA haplogroup may not contribute to disease progression after chronic HBV infection. Mixed results have also been seen in mtDNA haplogroups and diseases. For instance, European mtDNA haplogroups were associated with insulin resistance and atherogenic dyslipidemia52 but was not with hepatitis C virus (HCV) treatment response in HIV/HCV-coinfected patients53. A common European haplogroup, J, has been reported to be protective against Parkinson’s disease54 but increase the phenotypic expression of certain mutations of LHON55. These reports demonstrated that the role of mtDNA haplogroup in disease risk may differ in various populations, possibly influenced by environment, ethnicity, gender, age of infection onset, nuclear gene mutation, as well as coefficient of genetic variants.

We also found that CHBs belonging to haplogroup D5 showed a trend towards having a very high VL and a lower frequency of VL <100 IU/mL (Fig. 3), which was considered as the cut-off for clinical HBV-DNA negativity. All patients with a HBV DNA >20000 IU/ml are offered treatment clinically due to the strong correlation between high viremia, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)56. Among our patients who underwent serum quantification of HBV DNA, there were 5 of 12 (41.67%) in D5 CHBs and 41 of 154 (26.62%) in non-D5 CHBs with a HBV DNA >20000 IU/ml. This indicates a high occurrence of active HBV DNA replication among D5 CHBs. ALT is the most commonly used liver function parameter. Acute liver injury can be diagnosed by the increased level of ALT above 10 times of the upper limit of normal range (ULN, reference value as 0–40 U/L according to our hospital-based test)57,58. Only one out of 22 (4.55%) D5 CHBs and one out of 249 (0.40%) non-D5 CHBs who underwent ALT quantification had ALT >10 ULN (748 U/L and 451 U/L respectively). After excluding the highest ALT in D5 CHBs, the overall ALT did not significantly vary between haplogroup D5 and non-haplogroup D5 CHBs. This outcome was likely affected by the limited number of D5 participants available for analysis. Other liver function parameters including AST, TBIL, DBIL, TP and ALB showed no difference between D5 and non-D5 CHBs. These results further reinforced the likely role of haplogroup D5 as a risk for chronic HBV infection, but should be received with caution. Since D5 CHBs is a small group, the distribution of clinical parameters such as HBV DNA VL and ALT level were not well-proportioned, hence the high VL and ALT we observed in D5-CHBs may be occasional. Further validation using more clinical data of D5 is needed.

Antiviral drugs such as lamivudine and telbivudine may decrease mtDNA content measured by mtDNA copy number and affect mitochondrial function59. The insufficient information of drug treatment limited us from evaluating the mtDNA difference among HBV infected subpopulations and other aspects of mtDNA. Therefore, future study designs should also consider additional clinical aspects like antiviral drug treatment, HBV infection period and transmission routes. The limited sample size in this study, especially after dividing the overall CHBs into smaller categories, could affect the evaluation of clinical parameters. More samples are needed to investigate whether haplogroup D5 is associated with clinical parameters of liver function in CHBs. Lastly, the unavailable cell line of haplogroup D5 barred us from further detecting the influence of different matrilineal background on HBV infection. Functional assays to verify mtDNA haplogroup or certain mtDNA variation(s) in chronic HBV infection based on applicable cell line is needed.

In summary, we detected mtDNA haplogroup distribution in a general population which is composed of CHBs, SRs and HCs from Yunnan Province in Southwest China. We observed higher frequency distribution of haplogroup D5 in chronic HBV infected individuals than in SRs and HCs. The network results revealed a distinct distribution pattern of haplogroup D5 between CHBs and combined controls. Moreover, whether haplogroup D5 may confer risk to liver injury after chronic HBV infection needs to be solidified by more D5 samples. Future studies with larger sample size and functional assessment will be essential to identify the role of haplogroup D5 in chronic HBV infection.

Materials and Methods

Subjects

We enrolled 272 chronic HBV infected individuals (CHB), 278 spontaneously recovered (SR) subjects and 310 healthy controls (HC) who had never been infected by HBV. All of the HBV infected individuals were diagnosed with hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) positive for at least 6 months. Patients with HCV or HDV infection and alcoholic liver, fatty liver or autoimmune liver disease were excluded from enrollment. Those who were negative for HBsAg and positive for both anti-HBs and anti-HBc were defined as SRs. The SR and HC subjects were adults who come to hospital for physical examination. Recruitment criteria for each group were listed in Supplementary Table S2. Peripheral blood and clinical information including serum levels of HBV-DNA VL, ALT, AST, TBIL, DBIL, TP and ALB were collected. All of the individuals are from Yunnan province in Southwest China. Written informed consents conforming to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki were obtained from all participants prior to enrollment into this study. The experimental methods were carried out in accordance with the approved guidelines and regulations. All experimental protocols were approved by the institutional review board of the Second People’s Hospital of Yunnan Province.

mtDNA control region sequencing and haplogroup classification

Genomic DNA was extracted from the peripheral blood using EX-DNA whole blood genome kit (Suzhou Tianlong Bio-technology Co., Ltd.) by automatic Nucleic Acids Extraction System NP968 (Xi’an Tianlong Science & technology Co., Ltd.) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. The mtDNA control region sequence was amplified by using primer pair (L15575, 5′-ACACAATTCTCCGATCCGTC-3′ and H575, 5′-TGAGGAGGTAAGCTACATAAACTG-3′). PCR reactions were performed in a 50 μL reaction volume containing 45 μL of Jinpai MIX (green) (Beijing TsingKe Biotech co., Ltd.), 10 μM of each primer, and ~50 ng genomic DNA. The PCR condition was run under the following procedures: a pre-denaturation cycle of 98 °C for 2 min; 30 amplification cycles of 98 °C for 10 s, 57 °C for 15 s, and 72 °C for 30 s; and a final extension cycle of 72 °C for 5 min. PCR products were purified and analysed by the ABI PRISM TM 3730 × DNA analyzer (Applied Biosystems). Sequencing primers we used were as follows: L15996, 5′-CTCCACCATTAGCACCCAAAGC-3′; L29, 5′-GGTCTATCACCCTATTAACCAC-3′; L16209, 5′-CCCCATGCTTACAAGCAAGT-3′; H16347, 5′-GGGGACGAGAAGGGATTTGA-3′ and H575. For samples which could not be accurately classified based on the mtDNA control region sequence variation, a fraction of mtDNA-coding region was sequenced to justify the classification. Most of the primers used in this study were reported previously34,60.

Sequence variants of each sample were recorded based on the revised Cambridge Reference Sequence (rCRS)61. Each mtDNA haplogroup was assigned according to the latest version of the phylogenetic tree of human mtDNA (mtDNA tree Build 17, http://phylotree.org/tree/index.htm)62 and reconfirmed by the web-based bioinformatics platform mitotool (http://www.mitotool.org/)63.

Statistical analyses

Clinical information including gender, age, serum levels of ALT, AST, TBIL, DBIL, TP and ALB were compared in SPSS 17.0 and the PRISM software (GraphPad Software, Inc, La Jolla, CA, USA). We also compared the VL of HBV-DNA and ALT, AST, TBIL, DBIL, TP and ALB levels between CHBs with the haplogroup associated with chronic HBV infection and other haplogroups. Chi-square tests and unpaired student’s t test were used to examine the differences in clinical characters of participants. A P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. To examine the similarity of mtDNA genetic structures of our CHB, SR and HC sample sets, PCA was performed based on the mtDNA haplogroup distribution frequencies using the POPSTR software (Henry Harpending, 1997) incorporating published Han Chinese data from different regions across China. The frequencies of 26 main haplogroups collected from 36 published data sets together with our samples were used to conduct PCA. The published mtDNA data sets reanalysed in this study were shown in Supplementary Table S3.

To avoid potential bias caused by small sample size and to ensure the statistical power, only haplogroup frequencies shared by more than 3% of individuals in each subset of our cohort were considered to conduct statistical analysis. Due to the unmatched gender and age of SRs to the other two groups, potential association between mtDNA haplogroups and HBV infection was estimated by binary logistic regression with an adjustment for gender and age in each two groups. We further compared the mtDNA haplogroup frequencies in HBeAg positive and HBeAg negative patients by using the Fisher’s exact test (two tailed), considering that there were cases with cell counts below five.

Median-joining network for these mtDNAs belonging to the chronic HBV infection associated haplogroup based on the association analysis was constructed by Network 5.0.0.1 (http://www.fluxus-engineering.com/sharenet.htm)64. Considering that a wider range of variants may increase the complexity of the topological structure of the network, we used just the variants distributed in the HVS-I of mtDNA control region during the network construction. Due to the relatively small sample size of haplogroup D5, we put SRs and HCs together as a non-CHB control group to draw the network.

References

GBD 2013 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators. Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 385, 117–171 (2015).

Lee, W. M. Hepatitis B virus infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 337, 1733–1745 (1997).

Thursz, M. R. & Thomas, H. C. Host factors in chronic viral hepatitis. Semin. Liver Dis. 17, 345–350 (1997).

Moudi, B., Heidari, Z. & Mahmoudzadeh-Sagheb, H. Impact of host gene polymorphisms on susceptibility to chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Infect. Genet. Evol. 44, 94–105 (2016).

Heidari, Z., Moudi, B., Mahmoudzadeh-Sagheb, H. & Hashemi, M. The Correlation Between Interferon Lambda 3 Gene Polymorphisms and Susceptibility to Hepatitis B Virus Infection. Hepat. Mon. 16, e34266 (2016).

Wan, Z. et al. Genetic variant in CXCL13 gene is associated with susceptibility to intrauterine infection of hepatitis B virus. Sci. Rep. 6, 26465 (2016).

Moudi, B. et al. Association Between IL-10 Gene Promoter Polymorphisms (−592 A/C, −819 T/C, −1082 A/G) and Susceptibility to HBV Infection in an Iranian Population. Hepat. Mon. 16, e32427 (2016).

Huang, J. et al. Association between the HLA-DQB1 polymorphisms and the susceptibility of chronic hepatitis B: A comprehensive meta-analysis. Biomed. Rep. 4, 557–566 (2016).

Li, Y. et al. Genome-wide association study identifies 8p21.3 associated with persistent hepatitis B virus infection among Chinese. Nat. Commun. 7, 11664 (2016).

Zhu, M. et al. Fine mapping the MHC region identified four independent variants modifying susceptibility to chronic hepatitis B in Han Chinese. Hum. Mol. Genet. 25, 1225–1232 (2016).

Kim, Y. J. et al. A genome-wide association study identified new variants associated with the risk of chronic hepatitis B. Hum. Mol. Genet. 22, 4233–4238 (2013).

Mbarek, H. et al. A genome-wide association study of chronic hepatitis B identified novel risk locus in a Japanese population. Hum. Mol. Genet. 20, 3884–3892 (2011).

Anderson, S. et al. Sequence and organization of the human mitochondrial genome. Nature 290, 457–465 (1981).

Hajnoczky, G., Robb-Gaspers, L. D., Seitz, M. B. & Thomas, A. P. Decoding of cytosolic calcium oscillations in the mitochondria. Cell 82, 415–424 (1995).

Green, D. R. & Reed, J. C. Mitochondria and apoptosis. Science 281, 1309–1312 (1998).

Brookes, P. S., Yoon, Y., Robotham, J. L., Anders, M. W. & Sheu, S. S. Calcium, ATP, and ROS: a mitochondrial love-hate triangle. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 287, C817–833 (2004).

Dröge, W. & Schipper, H. M. Oxidative stress and aberrant signaling in aging and cognitive decline. Aging Cell 6, 361–370 (2007).

Pieczenik, S. R. & Neustadt, J. Mitochondrial dysfunction and molecular pathways of disease. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 83, 84–92 (2007).

Wang, D. et al. Mitochondrial DNA copy number, but not haplogroup, confers a genetic susceptibility to leprosy in Han Chinese from Southwest China. PLoS One 7, e38848 (2012).

Zhang, A. M. et al. Mitochondrial DNAs decreased and correlated with clinical features in HCV patients from Yunnan, China. Mitochondrial DNA A DNA Mapp. Seq. Anal. 27, 2516–2519 (2016).

Spandau, D. F. & Lee, C. H. trans-activation of viral enhancers by the hepatitis B virus X protein. J. Virol. 62, 427–434 (1988).

Zhang, S. M. et al. HBx protein of hepatitis B virus (HBV) can form complex with mitochondrial HSP60 and HSP70. Arch. Virol. 150, 1579–1590 (2005).

Siddiqui, A., Jameel, S. & Mapoles, J. Expression of the hepatitis B virus X gene in mammalian cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 84, 2513–2517 (1987).

Rahmani, Z., Huh, K. W., Lasher, R. & Siddiqui, A. Hepatitis B virus X protein colocalizes to mitochondria with a human voltage-dependent anion channel, HVDAC3, and alters its transmembrane potential. J. Virol. 74, 2840–2846 (2000).

Yang, B. & Bouchard, M. J. The hepatitis B virus X protein elevates cytosolic calcium signals by modulating mitochondrial calcium uptake. J. Virol. 86, 313–327 (2012).

Xia, W., Shen, Y., Xie, H. & Zheng, S. Involvement of endoplasmic reticulum in hepatitis B virus replication. Virus Res. 121, 116–121 (2006).

Cacciola, I. et al. Genomic heterogeneity of hepatitis B virus (HBV) and outcome of perinatal HBV infection. J. Hepatol. 36, 426–432 (2002).

Thursz, M. R. et al. Association between an MHC class II allele and clearance of hepatitis B virus in the Gambia. N. Engl. J. Med. 332, 1065–1069 (1995).

Chisari, F. V. & Ferrari, C. Hepatitis B virus immunopathogenesis. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 13, 29–60 (1995).

Lin, T. M. et al. Hepatitis B virus markers in Chinese twins. Anticancer Res. 9, 737–741 (1989).

Kamatani, Y. et al. A genome-wide association study identifies variants in the HLA-DP locus associated with chronic hepatitis B in Asians. Nat. Genet. 41, 591–595 (2009).

Hu, Z. et al. New loci associated with chronic hepatitis B virus infection in Han Chinese. Nat. Genet. 45, 1499–1503 (2013).

Chang, S. W. et al. A genome-wide association study on chronic HBV infection and its clinical progression in male Han-Taiwanese. PLoS One 9, e99724 (2014).

Wang, H. W. et al. Strikingly different penetrance of LHON in two Chinese families with primary mutation G11778A is independent of mtDNA haplogroup background and secondary mutation G13708A. Mutat. Res. 643, 48–53 (2008).

Bi, R. et al. Mitochondrial DNA haplogroup B5 confers genetic susceptibility to Alzheimer’s disease in Han Chinese. Neurobiol. Aging 36, 1604 e1607–1616 (2015).

Fuku, N. et al. Mitochondrial haplogroup N9a confers resistance against type 2 diabetes in Asians. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 80, 407–415 (2007).

Xing, J. et al. Mitochondrial DNA content: its genetic heritability and association with renal cell carcinoma. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 100, 1104–1112 (2008).

Wang, H. W., Xu, Y., Miao, Y. L., Luo, H. Y. & Wang, K. H. Mitochondrial DNA Haplogroup A may confer a genetic susceptibility to AIDS group from Southwest China. Mitochondrial DNA A DNA Mapp. Seq. Anal. 27, 2221–2224 (2016).

Claus, C. et al. Activation of the Mitochondrial Apoptotic Signaling Platform during Rubella Virus Infection. Viruses 7, 6108–6126 (2015).

Wang, C. et al. Circulating mitochondrial DNA content associated with the risk of liver cirrhosis: a nested case-control study. Dig. Dis. Sci. 60, 1707–1715 (2015).

Wheelhouse, N. M., Lai, P. B., Wigmore, S. J., Ross, J. A. & Harrison, D. J. Mitochondrial D-loop mutations and deletion profiles of cancerous and noncancerous liver tissue in hepatitis B virus-infected liver. Br. J. Cancer 92, 1268–1272 (2005).

Carelli, V. et al. Haplogroup effects and recombination of mitochondrial DNA: novel clues from the analysis of Leber hereditary optic neuropathy pedigrees. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 78, 564–574 (2006).

Zhang, A. M. et al. Mitochondrial DNA haplogroup background affects LHON, but not suspected LHON, in Chinese patients. PLoS One 6, e27750 (2011).

Baudouin, S. V. et al. Mitochondrial DNA and survival after sepsis: a prospective study. Lancet 366, 2118–2121 (2005).

Hwang, S. et al. Gene expression pattern in transmitochondrial cytoplasmic hybrid cells harboring type 2 diabetes-associated mitochondrial DNA haplogroups. PLoS One 6, e22116 (2011).

Niu, Q. et al. Effects of mitochondrial haplogroup N9a on type 2 diabetes mellitus and its associated complications. Exp. Ther. Med. 10, 1918–1924 (2015).

Hart, A. B., Samuels, D. C. & Hulgan, T. The other genome: a systematic review of studies of mitochondrial DNA haplogroups and outcomes of HIV infection and antiretroviral therapy. AIDS Rev. 15, 213–220 (2013).

Alexe, G. et al. Enrichment of longevity phenotype in mtDNA haplogroups D4b2b, D4a, and D5 in the Japanese population. Hum. Genet. 121, 347–356 (2007).

Li, X. Y. et al. Association of mitochondrial haplogroup D and risk of esophageal cancer in Taihang Mountain and Chaoshan areas in China. Mitochondrion 11, 27–32 (2011).

Milich, D. & Liang, T. J. Exploring the biological basis of hepatitis B e antigen in hepatitis B virus infection. Hepatology 38, 1075–1086 (2003).

Wu, S. et al. Hepatitis B virus e antigen physically associates with receptor-interacting serine/threonine protein kinase 2 and regulates IL-6 gene expression. J. Infect. Dis. 206, 415–420 (2012).

Micheloud, D. et al. European mitochondrial DNA haplogroups and metabolic disorders in HIV/HCV-coinfected patients on highly active antiretroviral therapy. J. Acquir. Immune. Defic. Syndr. 58, 371–378 (2011).

Guzmán-Fulgencio, M. et al. European mitochondrial haplogroups are not associated with hepatitis C virus (HCV) treatment response in HIV/HCV-coinfected patients. HIV Med. 15, 425–430 (2014).

van der Walt, J. M. et al. Mitochondrial polymorphisms significantly reduce the risk of Parkinson disease. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 72, 804–811 (2003).

Brown, M. D. et al. The role of mtDNA background in disease expression: a new primary LHON mutation associated with Western Eurasian haplogroup. J. Hum. Genet. 110, 130–138 (2002).

Tang, C. M., Yau, T. O. & Yu, J. Management of chronic hepatitis B infection: current treatment guidelines, challenges, and new developments. World J. Gastroenterol. 20, 6262–6278 (2014).

Björnsson, H. K., Olafsson, S., Bergmann, O. M. & Björnsson, E. S. A prospective study on the causes of notably raised alanine aminotransferase (ALT). Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 51, 594–600 (2016).

Xu, H. M., Chen, Y., Xu, J. & Zhou, Q. Drug-induced liver injury in hospitalized patients with notably elevated alanine aminotransferase. World J. Gastroenterol. 18, 5972–5978 (2012).

Xu, H. et al. Lamivudine/telbivudine-associated neuromyopathy: neurogenic damage, mitochondrial dysfunction and mitochondrial DNA depletion. J. Clin. Pathol. 67, 999–1005 (2014).

Zhang, W. et al. A matrilineal genetic legacy from the last glacial maximum confers susceptibility to schizophrenia in Han Chinese. J. Genet. Genomics 41, 397–407 (2014).

Andrews, R. M. et al. Reanalysis and revision of the Cambridge reference sequence for human mitochondrial DNA. Nat. Genet. 23, 147 (1999).

van Oven, M. & Kayser, M. Updated comprehensive phylogenetic tree of global human mitochondrial DNA variation. Hum. Mutat. 30, E386–394 (2009).

Fan, L. & Yao, Y. G. An update to MitoTool: using a new scoring system for faster mtDNA haplogroup determination. Mitochondrion 13, 360–363 (2013).

Bandelt, H. J., Forster, P. & Röhl, A. Median-joining networks for inferring intraspecific phylogenies. Mol. Biol. Evol. 16, 37–48 (1999).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all of the participants in this study. This work was supported by grants from Viral Hepatitis and Related Liver Disease Research Innovation Team of Yunnan Province (2015HC019), Health Research Institution Project of Yunnan Province (2014NS038, 2014NS039, 2016NS180, 2017NS125 and 2017NS126), Yunnan Provincial Department of Science and Technology-Kunming Medical University Joint Fund (2017FE468 and 2015FB081). N.O.O. thanks the CAS-TWAS President’s Fellowship Program for Doctoral Candidates for support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.W., L.Z. and T.-C.Z. designed the study; C.-H.W., L.-L.T., C.L., D.-Y.D., Y.T. and X.L. (Xin Lai) collected the samples and clinical information; X.L. (Xiao Li), T.-C.Z. and L.-J.C. carried out the experimental procedures; X.L. (Xiao Li) performed the statistical analysis; X.L. (Xiao Li), J.W., L.Z., R.B. and N.O.O. drafted the manuscript. All authors contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, X., Zhou, TC., Wu, CH. et al. Correlations between mitochondrial DNA haplogroup D5 and chronic hepatitis B virus infection in Yunnan, China. Sci Rep 8, 869 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-19184-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-19184-6

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.